Youth participatory action research (YPAR) is an innovative approach that stems from participatory action research (PAR), a methodology that emphasizes the co-creation of knowledge with those affected by the issues being studied. This approach values the insights of “insiders” in local contexts and aims to produce actionable knowledge that can lead to contextual improvements while building participants’ capacity for systematic inquiry (Domínguez & Cammarota, 2022). YPAR specifically involves youth as researchers, exploring equity issues relevant to their lives and advocating for change based on the findings (Ozer et al., 2020). Youth in YPAR settings undergo training to partake in a Freirean process of research, action, and reflection, contributing to a cycle that includes formulating questions, selecting methods, analyzing data, and reporting findings (Branquinho et al., 2020; Kirshner et al., 2011). These findings are leveraged for community benefit, with youth taking proactive steps to address the inequitable conditions they have studied.

To explore issues relevant to their lives, youth draw on various qualitative, quantitative, and geospatial methods (Marciano & Vellanki, 2022), methods that can have implications for addressing structural racism and promoting health equity. For example, utilizing qualitative and spatial methods (e.g., interviews and Photovoice) within YPAR can emphasize the perspectives of youth from historically marginalized communities, centering them in research and illuminating subjugated knowledge (Aldana et al., 2021; Collins, 1991; Mackey et al., 2021; Rose et al., 2022). YPAR groups can also leverage geospatial methods to explore and highlight structural inequalities as a result of processes such as redlining, blockbusting, and displacement (Akom et al., 2016; Anderson et al., 2024; Literat, 2013; Teixeira, 2015; Teixeira & Gardner, 2017). As a result, the methodological diversity within YPAR can be instrumental in exposing and challenging oppression, allowing youth to engage with issues of local importance in ways that resonate across various audiences (Bautista et al., 2013; Ozer, 2016). This approach enables youth to leverage local knowledge to envision alternative futures and challenge existing power imbalances (Bertrand et al., 2023; Cammarota & Fine, 2008; Ozer, 2016; Teixeira et al., 2021).

YPAR projects can be empowering settings for young people, especially youth from marginalized communities, to critically analyze and address systemic issues affecting their communities (Rose et al., 2022). By valuing the insights and experiences of youth, particularly youth of color and youth in low-income communities, YPAR processes can facilitate a deeper understanding of how structural racism manifests in the built environment, contributes to health disparities, and maintains systems of oppression (Caraballo et al., 2017; Langhout et al., 2014). YPAR projects and groups can play crucial roles in identifying and addressing systemic inequities that contribute to health inequities (Abraczinskas & Zarrett, 2020; Mirra et al., 2015). This approach can, therefore, be instrumental in revealing and challenging the underlying factors contributing to health disparities linked to structural racism.

YPAR and Urban Design

Young people are often left out of urban design and planning decisions (Derr et al., 2013; Mansfield et al., 2021). Their exclusion from these spaces reflects numerous social and structural barriers, including limitations on youth capacity, insufficient resources, and adultism (Bertrand et al., 2023; David & Buchanan, 2020). However, research has found that youth participation in urban design and planning spaces is fundamental for the equitable development of urban spaces (Anderson et al., 2024; Chawla, 2002; Frank, 2006; Nordström & Wales, 2019). YPAR centered on equitable urban design can create contexts for youth to engage in critical inquiry and collective action to address disparities in the built environment and significantly contribute to the design and development of healthy communities (Anderson et al., 2024; Teixeira & Gardner, 2017). Through their research, youth can examine and address issues such as unequal access to public amenities, disparities in urban development, and the impacts of environmental factors on community health. Methods such as community mapping, surveys, and data analysis are used by youth to identify and document disparities in their local environments. These diverse methodological approaches equip young people with concrete evidence to advocate for improving local conditions, challenging structural racism, and promoting healthy communities.

The Current Study

In this study, we describe the work of the Nashville Youth Design Team, a YPAR and design collective based in Metropolitan Nashville-Davidson County, Tennessee, to address structural inequities within the built environment. Focusing on the team’s most recent project, The Dream City Workshop, we describe the team’s action research process and how it addresses structural racism and improves health equity within Nashville. Moreover, we reflect on the team’s challenges and successes, their research approach, and the Dream City Workshop, describing how it can inform future YPAR projects focused on structural racism and health equity, particularly as manifested in urban built environments. Throughout the paper when we refer to “NYDT” or “the team,” we are referring to the youth co-researchers who collectively comprise the Nashville Youth Design Team; we will explicitly indicate the role of adult collaborators.

The Nashville Youth Design Team

The Nashville Youth Design Team (NYDT) is a YPAR and design collective based in Metro Nashville-Davidson County, Tennessee. Developed from a longstanding collaborative partnership between the Civic Design Center, a Nashville-based nonprofit that supports community engagement in urban design and planning, and researchers from Vanderbilt University, the NYDT seeks to improve youth health and well-being through research, design, and advocacy (Anderson et al., 2024; Morgan et al., 2024).

Origins of the Nashville Youth Design Team

The NYDT is an extension of Design Your Neighborhood (DYN), a middle school place-based action civics curriculum, created by the Civic Design Center and Vanderbilt University researchers (i.e., the third and fourth authors) and implemented in Metro Nashville Public Schools (see Morgan et al., 2022). The three-week curriculum focuses on learning about and addressing issues related to affordable housing, transportation, parks and open spaces, neighborhood identity, and sustainability within Nashville.

After four years of implementing the DYN curriculum, approximately 2,500 students were reached. The third and fourth authors recognized a need for continued engagement with DYN participants, primarily after students leave middle school and enter high school. To address this need, NYDT was established to continue engaging Nashville youth in leadership efforts to improve Nashville’s built environment and participate in decision-making spaces and processes. The NYDT was launched in May 2020. Since its inception, 30 high school students have been members of the NYDT, with 47% of team members participating for two or more years.

The Nashville Youth Design Team and YPAR

The NYDT is a paid, year-round internship consisting of 14–16 high school students from across Metropolitan Nashville-Davidson County. Team members represent different geographies, schools, and sociodemographics, offering diverse experiences and perspectives that inform the team’s research, design, and advocacy work. NYDT members typically join the team the summer before their first year of high school and can remain on the team through their senior year.

The team is supported by four adult collaborators: two Vanderbilt University graduate students (first and second authors); one former Vanderbilt University graduate student and current faculty member at Sewanee: The University of the South (third author); and the Civic Design Center’s Education Director (fourth author). Adult collaborators play an essential role in the team as they provide training on research methods and design work, assist with developing community partnerships, and provide administrative support (e.g., payroll and scheduling).

Using an iterative action research process that incorporates research, design, and advocacy, the NYDT (i.e., youth co-researchers) seeks to achieve four goals through their work:

-

Understand how local built environment factors impact youth wellness.

-

Engage in community-based research to understand the current state of the built environment, seeking to elevate underrepresented voices in urban design spaces.

-

Implement design interventions to address built environment challenges to improve the quality and accessibility of urban spaces for young people.

-

Address structural racism and work towards health equity through advocating for long-term sustainable changes within Nashville’s built environment.

The action research process used to achieve these goals begins during the summer with the NYDT Summer Intensive, a four-week program that incorporates research training, data collection and analysis, and design work. During the summer intensive, youth co-researchers conduct research, collecting data from their peers to understand how their neighborhoods impact their health and well-being. The team has used qualitative, quantitative, and spatial methods. The NYDT then analyzes the collected data (e.g., through basic descriptive statistics, thematic analysis, and geospatial analysis) and develops a list of themes that captures what young people see as strengths, challenges, and opportunities within Nashville’s built environment. The team then uses these themes to inform tactical urbanism interventions aimed at making urban spaces more accessible to young people; tactical urbanism projects are low-cost, temporary design interventions developed to imagine alternative urban spaces and activate long-term change (Lydon & Garcia, 2015).

Since 2020, the NYDT’s action research process has resulted in two tactical urbanism projects: 1) pedestrian safety measures at the most dangerous intersection in Nashville (2021); and 2) a mini-soccer pitch at a local park in a community with a large international population (2022). The designs were implemented by the NYDT with the assistance of adult collaborators and Civic Design Center staff during fall 2021 and 2022, respectively. In addition to the physical installation of the designs, the team also conducted community outreach to understand the impact of each project. For the pedestrian safety measures project completed in fall 2021, the team held community walks and conducted traffic audits. Their work attracted the attention of local news stations and local and state departments of transportation; later, the project was credited by the Tennessee Department of Transportation when announcing a $30 million street project on the pike where the design was implemented. For the mini-soccer pitch tactical urbanism project completed in fall 2022, the team held a soccer tournament where 43 community youth participated and more than 70 community members attended. At the tournament, the team also surveyed attendees to assess their valuation of the soccer pitch, learning that 58% of those surveyed stated that they would go to the park more often if the soccer pitch became permanent. In fall 2023, the NYDT’s mini soccer pitch design was submitted by the team as a part of a city-wide participatory budgeting campaign. Through the campaign, the design was selected by Metro Nashville residents as one of 24 projects to receive funding. Metro Nashville Parks Department is currently working to make the design permanent. Figure 1 provides images of the completed tactical urbanism projects.

As a result of their hard work, and as illustrated through the tactical urbanism projects over the past three years, the NYDT has been building power and developing a reputation in Nashville as a critical player in youth organizing and urban design spaces (Morgan et al., 2024). Due to this reputation, in winter 2023, the NYDT was invited by the steering committee co-chairs of Imagine Nashville, a city-wide community-based visioning initiative, to partner with adult leaders to facilitate the youth outreach for the initiative. In the section below, we briefly describe Imagine Nashville, including its origins, and the roles and work the NYDT has undertaken through this partnership.

Imagine Nashville & the Dream City Workshop

Imagine Nashville is the current iteration of a previous community-led initiative called Nashville’s Agenda. First developed in 1993 by a group of community leaders, Nashville’s Agenda was a “city-wide goal-setting process” that sought to capture perspectives from a diverse group of Nashville residents to create a list of “ideas for action” that would help guide the city’s development (Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee, n.d.; Nashville’s Agenda, 2007). The original iteration of the project resulted in a list of 21 goals for the city’s future and contributed to the development of the Frist Art Museum, the Nashville Housing Fund, and the Davidson Group. In 2007, a new group of community leaders reactivated the initiative. Still under the name “Nashville’s Agenda,” the group conducted surveys and community meetings to capture ideas about the city’s future from more than 3,000 individuals. The work resulted in a list of 58 actionable ideas focused on education, youth, immigration, economic and community development, poverty and homelessness, the environment, and transportation (Nashville’s Agenda, 2007).

Recognizing the need for a new list of values and priorities to guide the city’s development during a period of rapid growth, a group of community leaders came together in 2022 to reestablish Nashville’s Agenda, this time under the new name Imagine Nashville. Like previous iterations, Imagine Nashville is a city-wide, community-led effort to envision the city’s future (Imagine Nashville, 2024).

Unlike previous iterations of the initiative, Imagine Nashville has sought to incorporate young people’s perspectives into the envisioning process. In 2023, the NYDT, with support from the Civic Design Center, was invited to collaborate with Imagine Nashville to center youth voices within the initiative (Imagine Nashville, 2024). As a result, the NYDT (i.e., youth co-researchers), with the help of adult collaborators, developed the Dream City Workshop to achieve the following goals:

-

Capture young people’s opinions about life in Nashville in an engaging and educational way.

-

Center youth voices in the visioning and planning of the future of Nashville, providing young people with an opportunity to engage in civic processes and community planning efforts.

-

Explore what young people hope for the future of Nashville.

-

Capture ideas on how to improve spaces young people move through and inhabit in Nashville (i.e., schools, neighborhoods, parks, and roads/greenways).

In the following section, we briefly describe the Dream City Workshop, highlighting the mechanism through which the NYDT seeks to achieve its goals.

The Dream City Workshop

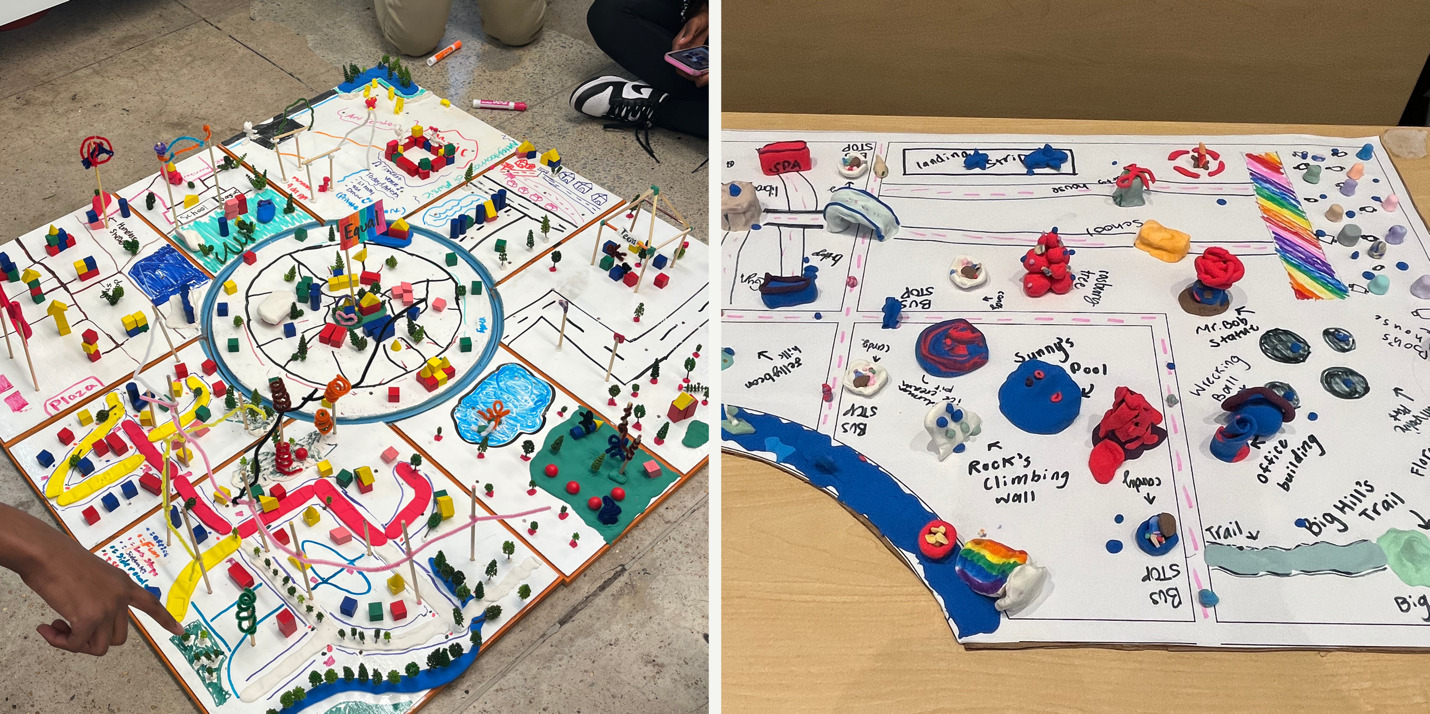

The Dream City Workshop is a two-hour design-thinking workshop created by the NYDT to explore and elicit young people’s perspectives on their ideal city. In Dream City workshops, workshop participants are invited to design a fictional dream city, where an emphasis is placed on the needs and preferences of young people rather than those of adults. Working in groups of four or five, workshop participants are assigned to design one of five sections, a “neighborhood” or the park, within the “dream city,” and asked to create elements they would like to see in their dream neighborhood. To create these designs, groups are provided with a wooden cutout (i.e., a piece of the city layout) and manipulatives to use in their designs. After about an hour of design work, the sections of the dream city (i.e., wooden cutouts) are assembled to construct a complete city (see Figure 2). Each group is then invited to present their designs, describing particular elements they chose to include in their city. These presentations are followed by a group discussion about the design process and the overlapping themes across the different groups’ designs. The workshop ends with a short 17-question reflection survey, where workshop participants are invited to translate ideas from their designs into their hopes for the future of Nashville. Through this workshop, the NYDT seeks to challenge adultism (Bertrand et al., 2023; David & Buchanan, 2020) and structural racism (Stacy et al., 2022) as they relate to urban planning and decision-making to improve youth health and wellbeing in Nashville (Teixeira & Gardner, 2017).

Between May and July 2023, the Dream City Workshop was facilitated by NYDT members and adult collaborators at 14 sites, engaging 620 young people between the ages of five and 18. Additionally, through the workshop, the NYDT collected surveys from 220 youth, capturing a diverse array of young people’s hopes and dreams for the future of Nashville.

NYDT Action Research Process: The Dream City Workshop

In the sections that follow, we use the NYDT’s action research process to explain the design and facilitation of the Dream City Workshop in detail (see Figure 3); we describe each step of the team’s process generally and how it was explicitly applied in the creation and facilitation of the workshop.

Steps One and Two: Exploring the Built Environment and Understanding Community Context

Steps one and two of the NYDT’s action research process include exploring the built environment and understanding community context. To do this, the team engages in neighborhood walk audits, research actions with community members (i.e., meetings structured to gain insights into people’s values and perspectives), collecting and analyzing secondary data, and reflecting on personal experiences. During these steps, the team starts to identify challenges within the built environment, situate these challenges within their historical, cultural, and geographic contexts, explore how they impact youth health and well-being, and determine a study context for their research.

Due to the exploratory nature of the Dream City Workshop and its goals, as well as the predetermined study context (i.e., Metropolitan Nashville-Davidson County), little exploration of the built environment and community context was done before developing an action research question. The hope was that the workshop and the data collected through it would shed light on the current state of Nashville’s built environment and highlight youth-identified strengths, challenges, and opportunities across various communities, also serving as a resource for future iterations of the team’s action research process.

However, one way the team (i.e., youth co-researchers) explored the built environment, as it related to the Dream City Workshop, was by identifying and defining spaces important to young people. For the past three years, the NYDT has used six built environment factors to guide their research and design work: 1) parks and open spaces; 2) affordable housing; 3) food resources; 4) neighborhood identity; 5) community resources; and 6) transportation. Instead of using these factors in the design and facilitation of the Dream City Workshop, the team developed a list of “Youth-Oriented Spaces” that they believed would be more accessible to young people.

To develop this list, NYDT members engaged in an iterative brainstorming exercise, answering questions outlined by adult facilitators such as, “If communities (i.e., neighborhoods and cities) were designed for young people, what would they look like?” “How could we make spaces more inclusive?” “What would (not) be in these spaces?” Using the lists constructed during this exercise, the team developed and defined a list of eight youth-oriented spaces. The final list is presented in Figure 4.

Step Three: Action Research Question and Hypothesis Development

After compiling and analyzing background information on the built environment and community context, youth co-researchers develop an actionable research question that considers community context and the current state of the built environment.

For the Dream City Workshop, the team drew inspiration from the eight youth-oriented spaces, posing the following question: What would a city (i.e., Nashville) look like if it was designed for young people?

Step Four, Part One: Research Tool Development

Once the action research question is defined, with the guidance of adult collaborators, the NYDT creates a research tool that collects the data needed to answer their research question. Prior to the Dream City Workshop, the NYDT had only used surveys (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, geospatial) and interviews to gather data from their peers. For this project, adult collaborators encouraged the NYDT to create a new outreach tool that would take one of their frequently used design processes, a charrette, and use this approach to create a workshop that would harness the creativity and imagination of young people into the design of an ideal city for youth. A design charrette is a collaborative process where a group of people, typically adults, think through a problem in their community and draw out solutions on a map (see next section for more information on how the NYDT adapted the design charrette tool for the Dream City Workshop; Howard & Somerville, 2014; Neuman et al., 2022; Sutton & Kemp, 2006). Using the framework of a charrette, the team drew upon the list of eight youth-oriented spaces they identified in step one of their action research process to develop a workshop that would ask youth participants to design their ideal city. To encourage youth participants to think outside the box while designing their dream cities, a youth co-researcher developed a short video that integrated images and video clips of imaginative worlds in pop culture. The video was shown to workshop participants prior to the design phase. It was also during the workshop development stage that another youth co-researcher (i.e., a NYDT member) came up with the name “Dream City,” to communicate what they envisioned as the fun and imaginative nature of the workshop. To increase workshop accessibility, all materials were available in both Spanish and English. Next, we briefly detail the NYDT’s unique design charrette approach before discussing the development of the workshop’s data collection tools.

Design Charrettes Designed for Young People

A design charrette is a tool used by designers and planners (e.g., architects, city planners) to involve residents in addressing community-identified problems through creative design thinking (Neuman et al., 2022). During a charrette, small groups collaborate to brainstorm and design spaces that tackle identified problems (Sutton & Kemp, 2006). Typically, this process engages adults with limited participation from young people (i.e., people under the age of 18; for exceptions see Rottle & Johnson, 2007; Sutton & Kemp, 2002). Through the Dream City Workshop, the NYDT modified the concept of a design charrette, making it more accessible to young people. The key adaptation was changing the objective of the charette from addressing specific place-based issues to inspiring creative and imaginative thinking that could later be translated into real-world ideas. For example, within the Dream City designs, participants designed various modes of transportation, such as flying cars, moving sidewalks, and youth-only buses. The flexibility of the charrette allowed workshop participants to develop inventive solutions while also highlighting issues that are important to youths (i.e., accessibility and mobility). By tailoring this widely used design tool, the NYDT offers an innovative approach for capturing youth perspectives on the built environment and identifying youth priorities within public spaces. Furthermore, the youth-oriented charrette functions as a valuable instrument for youth organizing groups to center youth perspectives and ideas within planning and decision-making spaces.

Identifying and Creating Data Collection Tools

To capture data during the Dream City Workshop, the NYDT developed and utilized a variety of data collection tools to capture workshop participants’ opinions and values.

-

Audio recordings of the Dream City design presentations.

During the group presentations, one workshop facilitator, typically an adult collaborator, would be responsible for recording the presentations through a phone-based audio recording app.

-

Photos of the Dream City designs for each workshop to document design ideas.

Following the design presentations, one workshop facilitator, typically an adult collaborator, would be responsible for taking pictures of the Dream City designs.

-

Short survey/series of reflection questions to ask following the design presentations.

Because the Dream City Workshop is part of the larger Imagine Nashville initiative, questions similar to those on the adult survey were required in the youth survey. Working off the questions provided by Imagine Nashville, the team revised and condensed the adult questions to make them more accessible to young people. Additionally, they added questions focused on safety; the Dream City Workshop was developed in the wake of the school shooting at The Covenant School in Nashville, re-emphasizing the need to design for safety. The 17 revised questions were coded into the qualitative research platform Recollective by an adult collaborator and organized into four categories: “Things I like about living in Nashville”; “Things I don’t like about living in Nashville”; “Safety and Belonging in Nashville”; and “Changing Nashville for the Better.” The survey questions can be found in Appendix A.

To increase accessibility for Spanish-speaking participants, a Spanish-speaking adult facilitator offered translation during the workshops, and Dream City surveys were also translated into Spanish.

Step Four, Part Two: Data Collection

The facilitation of the Dream City Workshops served as the mechanism through which data was collected. Between May and July 2023, the Dream City Workshop was facilitated by NYDT members and adult collaborators at 14 youth-serving or youth-oriented organizations, engaging 620 young people between the ages of five and 18. Twelve Dream City presentations were recorded, more than 200 Dream City designs were photographed, and 220 surveys were collected.

These presentations and designs were intentionally collected from a variety of neighborhoods and youth-serving settings in the city. When choosing locations to implement the workshop, for example, geographic diversity was prioritized. Ensuring different neighborhoods were represented naturally led to demographic diversity. The workshop was also adapted to accommodate two location types. The first was a classroom-like setting, utilized for summer programs such as summer school and summer camps. The second was a come-and-go set-up where the workshop and survey activities were set up for youth participants to join and contribute as they please. This set-up was utilized for tabling at festivals, the Nashville Fair, and the Adventure Science Center’s i2 Makerspace. The Civic Design Center’s youth programs have built relationships with schools and other youth programs across the city, which were valuable when scheduling these workshops.

Due to the complexity of scheduling the Dream City workshops, NYDT adult collaborators created a system to manage the logistics of scheduling workshops and assigning NYDT members and adult facilitators to each workshop. This system was managed by an NYDT adult collaborator and included handling all communication between community partners and facilitators. Due to all the moving pieces, it was crucial to have one consistent adult collaborator managing these daily details to ensure clear communication with partners and facilitators. A spreadsheet was also developed to keep track of the information for each scheduled workshop, including number of participants, location, and assigned facilitators. A shared Google calendar was created to assign NYDT members and adult facilitators to each workshop.

Step Five: Data Analysis

After data has been collected, the team moves on to data analysis. Historically, this has included quantitative (i.e., basic descriptive statistics), qualitative (i.e., thematic coding), and geospatial (i.e., mapping data and identifying patterns) analysis. Various software tools have been used during the analysis process, including Excel, Quirkos (a qualitative data analysis software), Google My Map, Google Sheets, and ArcGIS Online. Data analysis has sometimes been done without the use of technology, though we have found that technology typically speeds up the analysis process and results in more accurate findings. We have also found that the data analysis stage requires substantial time and adult support, both for training and conducting the analyses.

For the Dream City Workshop, youth co-researchers analyzed Dream City presentation transcripts, Dream City design photographs, and youth survey responses. The team used an iterative cycle of deductive and inductive coding to thematically code the data. Through analyzing the data, the team identified recurring themes and developed a set of youth priorities for Nashville’s built environment.

Coding Process

The NYDT utilized Quirkos, software for qualitative data analysis, to code the Dream City presentation transcripts and survey responses. Quirkos was selected by adult collaborators because it allowed the team to engage in real-time collaborative coding. The coding process was conducted in two phases. During the first phase, team members coded the presentation transcripts. Utilizing both inductive and deductive coding, youth co-researchers worked in pairs to code the different design elements included in workshop participants’ Dream City designs. The eight youth-oriented spaces were populated as deductive codes prior to analysis; however, team members were also encouraged to create new inductive codes based on themes that emerged from the data.

Before starting the second phase of coding, NYDT members were assigned one of the eight youth-oriented spaces to focus on. Focusing on their assigned youth-oriented space, team members were asked to review the data coded under that space and to develop a list of emergent themes. These themes were presented to the rest of the team and populated as codes for phase two.

During the second phase, the team coded the survey data. To do this, the team was divided into four groups, and each group was assigned one section of the survey (e.g., “Things I like about living in Nashville”; “Safety and belonging in Nashville”). Using the eight youth-oriented spaces and the emergent themes identified within those spaces, the groups deductively coded the survey data.

The team used Google Jamboard to analyze the design photos. Prior to the meeting where the photos were analyzed, an adult collaborator arranged the photos on pages in Jamboard. Team members were then assigned portions of Jamboard and tasked with reviewing the photos and adding codes in the form of sticky notes based on the designs. We found that photo analysis of was the most difficult and tedious part of the data analysis process.

Priority Statements

After coding, the team identified recurring themes that appeared throughout the Dream City designs, presentations, and survey responses, including: “General youth quality of life,” “Accessibility in Nashville,” “Neighborhood safety/belonging/community,” “Transportation,” “Safety,” “Outdoor spaces and places,” and “Expensive to live in Nashville.”

Using the previously listed themes, the team (i.e., youth co-researchers) worked individually to generate youth priorities, creating a total of 21 youth priorities. Between meetings, an adult collaborator (second author) arranged the priorities developed by the team into five overarching priority areas: 1) transportation; 2) affordability; 3) having youth-centered and fun spaces and places; 4) safety; and 5) proximity to youth-oriented spaces. The adult collaborator wrote summary statements that encompassed all the priorities listed in each area. Using these summaries as a guide, the team worked in groups to develop priority statements for each of the five priority areas. These five priority statements (outlined below) would guide the team’s design work.

Nashville Youth Priority Statements

-

Young people in Nashville want simple, local, safe, and close transportation to move around the city and to common areas. Young people want better access to resources and fun spaces.

-

Accessibility and affordability are two words that do not go together in Nashville, and the youth of Nashville want to create a Nashville that is both accessible and affordable for the next generation.

-

A priority for young people living in Nashville is having access to safe, local, entertaining, and welcoming spaces. They want more youth-geared spaces that consider what they value and are accommodating to them specifically. They want spaces that help them build relationships and meet new people.

-

Young people in Nashville want to feel safe. When they go out for activities, they don’t want to worry about their own safety being compromised. Having a sense of safety will encourage youth to be more active in the community rather than feeling constant fear.

-

Youth value places to have fun that are important to them and transportation support to places further out. Transportation is a struggle for all and this includes youth.

Step Six: Data-Informed Design & Advocacy

The final step in the NYDT’s action research process is data-informed design and advocacy. The data-informed design portion of this step involves small groups (three to four people) creating tactical urbanism design interventions to address a challenge(s) identified through the research findings. The design intervention must stay within a $2,000 materials budget and be able to be built by the NYDT in a weekend. The advocacy portion of this step typically includes the Youth Voice Exhibition (discussed in more detail below), the tactical urbanism design installation, and community outreach around the design, including community meetings, surveys, and press releases.

For the Dream City Workshop, the NYDT was divided into four groups based on which priority statement they found to be the most interesting; it was determined that safety would be incorporated into every group’s design. Typically, the NYDT would design a tactical urbanism intervention to solve a problem related to the priority statements, but this summer, the NYDT created visionary designs that will be included as recommendations in the final Imagine Nashville report. The NYDT will later create tactical urbanism interventions to advocate for their visionary designs.

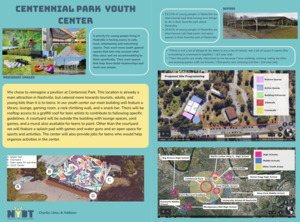

To create the designs, the teams worked with their design advisors (i.e., Civic Design Center design staff and interns) to determine the location and programming of their design, considering their group’s priority statement. Once outlined, the groups worked on collecting and developing six design components needed in their final design board and presentation: 1) before photos of the site; 2) a site plan (i.e., how the site would be used); 3) perspective drawings of the design intervention, either hand-drawn or created using Gimp, a free photo editing software; 4) site diagrams (e.g., accessibility, programming); 5) data from the Dream City Workshop to justify their design; and 6) a one-to-two paragraph write-up describing the design and connecting it to their priority statement. These elements were then incorporated into each group’s design board (see Figure 5 for an example of a design board) and Youth Voice Exhibition presentation slides. The designs developed during the 2023 summer intensive included transportation infrastructure improvements in North Nashville, a youth way-finding route in East Nashville, youth-oriented improvements at a park in Northeast Nashville, and a youth center at a park in Midtown Nashville.

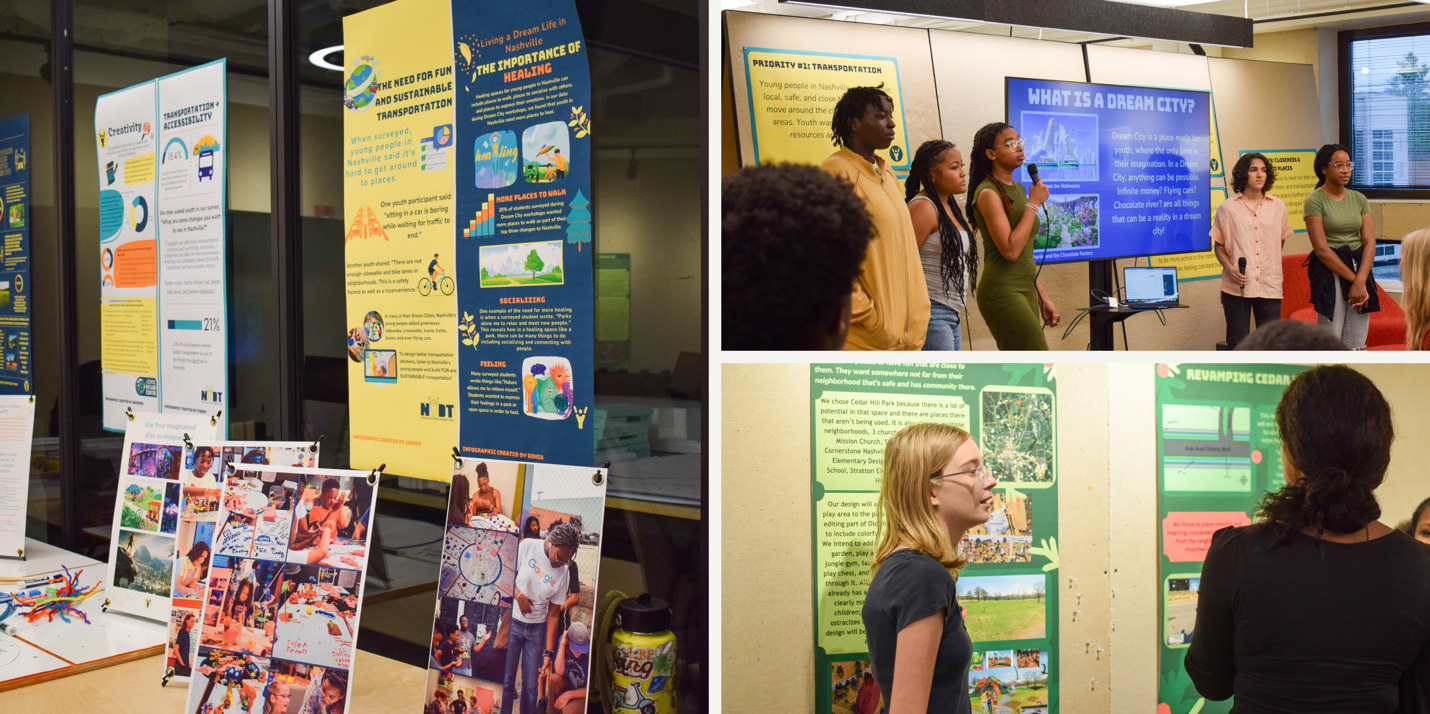

The Youth Voice Exhibition

The Youth Voice Exhibition marks the end of the summer intensive and serves as an opportunity for the team to share their research with the public, including family and friends, architects and designers, community leaders, Metro Nashville government employees, and elected officials. During the exhibition, the team presents the work they conducted over the summer, highlighting the designs they developed to address specific challenges within the built environment. After the presentations, there is a short Q&A session, followed by a chance for audience members to vote on the design they want to see implemented during the school year. Following the formal events of the exhibition, there is a short reception where attendees can interact with and ask questions to team members. The exhibition typically lasts an hour, and a virtual streaming option, such as Zoom, is also offered.

More than 70 in-person guests attended the 2023 Youth Voice Exhibition. During the exhibition, the team presented on the development and implementation of the Dream City Workshop and their work from the Summer Intensive, specifically showcasing their design interventions. See Appendix B for the complete set of slides from the 2023 NYDT Youth Voice Exhibition. Following the presentations, attendees voted for their favorite design; the winning design of the 2023 Youth Voice Exhibition was a youth center at Centennial Park, a prominent park in the city. Figure 6 presents images from the 2023 NYDT Youth Voice Exhibition.

Next Steps

The NYDT has continued to facilitate Dream City workshops throughout the city. Since the summer of 2023, the Dream City Workshop have been facilitated at 30 sites, engaging more than 2,000 young people and collecting more than 1,181 surveys. During fall 2023, NYDT adult collaborators worked to get the workshop approved by Metro Nashville Public Schools (MNPS) to enable workshop facilitation in MNPS schools. As a result, the workshop was written as a lesson plan that was aligned with Tennessee state learning standards. The team plans to continue to facilitate the Dream City Workshop in classrooms and after-school programs through the end of the 2023–24 school year. The data collected during this time will be used during the 2024 Summer Intensive, where the team’s action research process will begin again.

Key Takeaways from the Nashville Youth Design Team and the Dream City Workshop

Having discussed the NYDT’s action research process and how it shaped the Dream City Workshop, we next consider the successes and challenges that these efforts have faced, as identified by NYDT members, adult collaborators, and adult facilitators of the Dream City Workshop.

The Nashville Youth Design Team

Since forming in 2020, The Nashville Youth Design Team has navigated a path marked by achievements and challenges in promoting more robust youth participation in local urban design through participatory action research.

Successes

NYDT has established itself as a key player in local urban design and youth organizing spaces. This is in large part due to team members’ (i.e., youth co-researchers) duration and consistency of engagement. Over the past four years, 30 high school students have been members of the NYDT, with 47% of all team members participating for two or more years. In 2024, the NYDT will graduate the first team member who has been part of the team for all four years of high school. This long-term engagement has enabled youth team leadership, as well as sustained a leadership cycle where team members who have been involved longer train and lead newer team members (i.e., first year team members), contributing to a strong and continuing team culture. Additional strengths of the NYDT are discussed below.

Increased capacity. The involvement of multiple team members spanning multiple years has increased the team’s capacity to engage in meaningful action research and design work in Nashville. Because of the seasoned team members, each year, the research and design work builds off prior years, resulting in more creative data collection tools, increased rigor in data collection and analysis, and more detailed and knowledgeable designs. The growth around the team’s iterative action research process has also attracted the attention of adult stakeholders, leading to increased community partnerships and opportunities to engage in city-wide decision-making spaces (e.g., the Dream City Workshop).

Empowering context. NYDT has served as an empowering context for youth co-researchers from across Nashville. When reflecting on their time with the team, the fifth and sixth authors (a first-year team member and a third-year team member) shared that being part of the NYDT has provided a space where they can collaborate with other young people to make tangible differences in local communities; a relatively unique experience for most young people. They also shared that being part of the team has given them the opportunity to gain work experience and exposure to “real world” projects, making connections that have the potential to help them reach personal or professional goals. Ultimately, the fifth and sixth authors believe that throughout their time on the NYDT, the team has connected with young people from across the city and elevated youth voices in urban planning and decision-making spaces.

Challenges

Despite the notable strengths of the NYDT, there have also been several challenges the team has had to overcome.

Engagement and participation during the school year. One of the biggest challenges the NYDT has experienced is maintaining engagement with team members during the school year. After the four-week summer intensive, the NYDT holds monthly Saturday morning meetings throughout the school year to complete their tactical urbanism designs and continue advocacy for the priorities identified over the summer. While Saturday mornings have proven to be the time the team is most available during the school year, many have conflicting commitments, such as jobs and other extracurricular activities. It is also challenging to keep momentum going when the meetings are infrequent. One way adult collaborators have addressed this challenge is offering flex work, or additional paid opportunities, between meetings as an avenue for providing extra touchpoints.

Consistent funding. The NYDT was initially funded through a community partner contract with Vanderbilt University through a National Institute of Justice (NIJ) grant. The team’s role in the grant was to contribute to a dataset about young people’s perceptions of spaces in their neighborhood (see Anderson et al., 2024). This grant funded the first two years of the NYDT program. Since its end, funding has come from a series of local grants and sponsorships, including Imagine Nashville, which is the most recent. In addition to seeking financial support to fund the day-to-day activities of the team, the Civic Design Center also seeks financial partnerships to fund the tactical urbanism design installations. Not having a consistent funding source has been a challenge, requiring the Civic Design Center to be proactive about building relationships with financial partners.

Transitions in adult collaborator leadership. The adult collaborators who lead the research portion of the NYDT are PhD students, which means they typically leave Nashville after graduation (i.e., roughly five years). This has presented challenges in maintaining the fidelity and design of the research component of the program. Keeping the NYDT’s methods rooted in the YPAR process has been critical in ensuring consistency and quality in the NYDT’s research. As the PhD students build out lessons and activities for the NYDT, they ensure they are written in a way that can be reused in the future. Furthermore, a staffing structure has been developed so there are always two PhD students working with the NYDT, one student who is new to the program and the other in their third to fifth year. The more advanced graduate student has a higher level of responsibility and acts as a mentor to the newer student. Stability is added by the Civic Design Center’s Education Director being a consistent collaborator. Furthermore, the NYDT is a formalized program within the Civic Design Center, which has provided the structure needed to ensure continuity despite changes in adult collaborator leadership.

The Dream City Workshop

Reflections on the Dream City Workshop illustrate successes and areas for growth that can inform future efforts to engage youth in discussions about creating a more equitable built environment.

Strengths

Overall, the Dream City Workshop has received positive feedback from youth participants and their adult facilitators. Workshop participants are consistently excited to dive in and thoughtfully and meaningfully engage with the content, including the survey. We attribute this energy and excitement to the workshop’s design (i.e., design charrette), as it engages young people in a fun, hands-on activity that requires them to be creative. Below, we outline additional strengths of the Dream City Workshop as an approach to participatory research and action to address inequities in the built environment.

Widespread and diverse engagement. The workshop has been effective in engaging a diverse group of young people, particularly across age, race/ethnicity, ability, and geographic locations in the city. This reach has allowed the NYDT to collect a wide range of experiences and hopes for the future of Nashville. Since implementation of the workshop began in May 2023, 79 workshops have been held, engaging 2,000 young people and collecting more than 1,000 survey responses.

Robust data. The data collected through workshops and surveys have been richer and more extensive than previous NYDT-led data collection processes. Having the workshop precluding the survey has also led to more meaningful engagement with the survey. The applied workshop helps participants to make connections between their Dream City and their immediate environments (e.g., neighborhood, city).

Meaningful civic participation. The accessibility of the Dream City Workshop, as well as its direct connection to the Imagine Nashville initiative, has enabled young people from across the county to participate in city-wide efforts to envision the future of Nashville. As a result, the workshop has served as a catalyst for engaging young people between the ages of five and 18 in meaningful civic participation. Through the workshop, youth are invited to imagine alternative futures for the city of Nashville and then communicate their preferred alternatives through the survey. As a result, the NYDT has been able to center youth voices in the Imagine Nashville initiative, providing young people with an opportunity to engage in civic processes and community planning efforts, with the hope of designing and building a city that is more equitable for all.

Challenges

Alongside the strengths and accomplishments of the Dream City Workshop, challenges have arisen.

Workshop logistics. Due to the complexity of the workshop, numerous logistics had to be considered during the implementation stage. This included scheduling workshops, assigning NYDT and adult facilitators, and managing workshop materials. In any given week, the team could facilitate upwards of seven workshops, interacting with more than 300 young people. As a result, ensuring that at least three facilitators were at each site and equipped with all the necessary design materials proved to be a juggling act. Additionally, the materials used in the workshop, with the exception of the design layouts, have a limited life span, requiring a constant restocking of the material boxes. To address these logistics, one adult collaborator was responsible for scheduling and assigning facilitators to workshops, and a Civic Design Center intern was responsible for keeping the workshop supplies stocked and organized. We found that giving multiple people small but specific roles distributed the workload and resulted in successful workshop implementation.

Workshop adaptations. Over time, we found that the workshop required adaptations to fit the varying spaces, levels of experience, ages, and primary languages of participants as well as the time allotted by community partners. Moreover, there was a need to find the right balance of design constraints to ensure workshop participants had enough direction to design a city that felt meaningful to them but not too much direction to stifle creativity. As a result, in September 2023, the NYDT launched phase two of the workshop. In phase two, the team drew from their summer work and identified five themes; these themes would replace the eight youth-oriented spaces and serve as the guide for workshop participants’ dream city designs. We found that these themes have inspired more personality and creativity in the designs, but workshop participants often focus too much on incorporating their group’s theme, leaving out critical parts of a city, such as housing and food resources. To address this challenge, workshop facilitators adapted their support methods and focused their questioning on asking participants what else their neighborhood needed to support the people who live there.

Structural Racism & Health Equity

The NYDT’s work to address structural racism and health equity through YPAR presents a complex landscape of ongoing successes and challenges.

Successes

Focus on health equity. Since 2020, the NYDT has explicitly focused on utilizing research and design to address the health and well-being of young people in Nashville. At its inception, the team’s initial research question sought to explore what young people in Nashville needed to be healthy and well, utilizing a holistic definition of wellness, which included physical, environmental, recreational, social, financial, intellectual, spiritual, and mental wellness. For two years, the team surveyed their peers to understand youth wellness and explore the relationship between health and the built environment (see Anderson et al., 2024 and Morgan et al., 2024). This focus enabled the team to engage in more extensive conversations around health equity in Nashville, advocating for changes in Nashville’s built environment that would improve the health and well-being of not only youth but all Nashvillians. Though the team’s research question has evolved, youth health and well-being continue to remain at the center of the team’s work. When developing the Dream City Workshop, the team discussed how the various youth-oriented spaces impacted youth health and sought to create spaces that were safe and supportive of young people. Throughout the team’s various projects, they have continuously advocated for the idea that when cities are designed with young people in mind, they become more accessible for everyone, thus positively contributing to the collective health and well-being of the greater community.

Participatory research and urban design to address structural racism. Participatory processes, including the process envisioned and executed through the Dream City Workshop, can provide essential input for long-term transformation. Through their work, the NYDT has engaged in more extensive conversations in Nashville around how structural and environmental racism are represented in the built environment. One such manifestation of structural racism the team has identified is young people’s restricted access to (or exclusion from) public spaces, particularly in neighborhoods experiencing high levels of police surveillance and structural disinvestment. The work of the Youth Design Team illustrates the potential for youth-led research and urban design to work to combat these manifestations of structural inequities in the built environment.

Challenges

The NYDT has faced several barriers to addressing structural racism and health equity through YPAR. These challenges underscore the need to deepen our understanding of the local Nashville context and offer youth more opportunities to reflect on these systemic issues.

Context of Nashville. Metro Nashville’s history of structural racism in urban planning and housing and transportation policy, including redlining and the construction of Interstate 40 (see Mohl, 2014, for a history of community resistance to the construction of Interstate 40), has informed the present structural disinvestment in Nashville neighborhoods. Moreover, it has contributed to young people’s experiences within their neighborhoods. Imagine Nashville and the Dream City Workshop aim to envision the future of Nashville, and young people of color’s reflections on their experiences of the city will be core in building a more equitable city in the coming years. The embeddedness of structural racism in Nashville’s built environment and the broader structural practices that marginalize youth in decision-making spaces make it difficult to center youth voices in more extensive planning processes. To address this challenge, the Dream City Workshop has worked to be intentional about gathering young people’s insights on their experiences of the built environment in an effort to combat structural inequities.

Critical consciousness development. The development of critical consciousness is an ongoing process. While discussions about racism, structural racism, and environmental racism emerge during NYDT’s initiatives and the Dream City Workshop, these topics are not the central focus of their work or the workshops. In conversations about urban planning in Nashville, issues of structural racism, particularly of gentrification and displacement, naturally surface due to their significant impact on the city’s communities of color. Nevertheless, there is some ambiguity regarding how each NYDT member perceives their role in addressing structural racism and the degree to which they view their participation in NYDT and Dream City as aligned with this vision. Understanding that the development of critical consciousness is a transformative process emerging from a cycle of action and reflection, there is significant potential to deepen this process for youth involved with Dream City and the NYDT by creating intentional spaces and opportunities for reflection, particularly regarding structural racism.

Conclusion

Youth participatory action research (YPAR) can be a promising approach for engaging young people in inquiry and action to address issues in their communities, including those related to built environments and neighborhoods (Bautista et al., 2013; Ozer, 2016). This study has detailed the work of the Nashville Youth Design Team (NYDT, a YPAR and urban design collective) as it developed and led the Dream City Workshop — a city-wide effort to gather perspectives and visions from a broad array of young people across the city, to synthesize and analyze those perspectives and visions, and then to use the findings to design, implement/build, and advocate for concrete changes to the built environment that can address systemic inequities. The NYDT’s approach to action research and the design of the Dream City Workshop (i.e., design charrette) can be a valuable model for other efforts to implement YPAR, particularly as it relates to making urban areas more equitable and capable of supporting the well-being of young residents.

Recommendations for Future YPAR Projects

Although the longer-term impacts of the work of the NYDT on Dream City and Imagine Nashville remain to be seen, in this final section, we reflect on some of the immediate successes and challenges faced by the NYDT during the Dream City Workshop, and from these derive a set of recommendations for others attempting to cultivate similar locally focused action research projects and collectives.

-

Develop a strong core team of leaders before attempting large-scale projects (like Dream City). The fact that the NYDT (youth co-researchers and adult collaborators) had already developed a shared understanding of an approach to research and action on the built environment equipped the group to be able to design and implement a larger-scale participatory research project that engaged large numbers of young people from across the city in helping to determine city-wide priorities.

-

Work with the core team to consider and negotiate potential projects, partnerships, and opportunities. The NYDT was asked to lead the youth engagement portion of the Imagine Nashville visioning process because it had already established a strong reputation for youth leadership in local decision-making. The group carefully considered the opportunity for partnership with this larger initiative and ultimately proposed an approach to broaden youth engagement that was consistent with the NYDT’s longer-term goals.

-

Seek to elicit imagination, vision, and creativity. Many approaches to action research engage participants only in studying the world as it is to the neglect of the world as it should be. Documenting imaginative ideals like the Dream City did can be engaging for participants and can yield findings that highlight gaps between present reality and more just and equitable futures.

-

Use hands-on activities and visually stimulating techniques. Although the Dream City Workshop made use of some of the more common approaches to social research (i.e., survey data collection; qualitative data analysis), it also developed novel techniques for engagement and communication of perspectives that were tactile and that created visually interesting representations (i.e., design charrette).

-

Create contexts for participants to connect personal experiences and preferences to systems and features of environments. The NYDT and Dream City Workshop orient their work to changes in the built environment, which are continuously shaped by policy and systems (e.g., transportation systems) that can contribute to or detract from health equity. This orientation to changes in the built environment naturally spotlights structural inequities and determinants of well-being and directs attention away from, for instance, individuals’ beliefs, motivations, or health behaviors.

-

Consider possibilities for generating short-term wins. The Nashville Youth Priority Statements identified through the Dream City Workshop could take decades of community organizing and advocacy to fully achieve. While it is essential to be unrestrained in establishing a vision for more equitable futures, it is also valuable to identify concrete actions that can be taken in the near term to begin improving local policies, systems, and environments. The tactical urbanism design and installation provide a concrete first action step toward realizing longer-term visions.