Introduction

The aims of health system improvement emphasize the importance of equitable access to care in addition to optimal health outcomes, cost-effective care, and positive patient and provider experiences (Nundy et al., 2022). Using maternal mortality rates as an indicator of quality perinatal care, rates in Canada suggest relatively high-quality care when compared to low- and middle-resource countries (United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-agency Group, 2023). However, there are considerable perinatal health disparities between Indigenous (Bacciaglia et al., 2023; Kolahdooz et al., 2016; Miao Id et al., 2022; Turpel-Lafond, 2020), Black, and the predominately white populations living in Canada (McKinnon et al., 2016; Miao Id et al., 2022). Recent immigrants or refugees, people who identify as Indigenous (First Nation, Inuit, and Métis), people from racial, sexual, and gender minority groups, and those who live with disabilities are also more likely to have increased perinatal morbidities, including miscarriage, stillbirth, low birth weight infants, preterm birth, postpartum depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, reductions in breastfeeding rates, and a host of other poor perinatal outcomes (Bacciaglia et al., 2023; H. K. Brown et al., 2021; Center for Disease Control & Prevention, 2023; Chartier et al., 2022; Everett et al., 2019; Miao Id et al., 2022; Tarasoff et al., 2020). These disparities are compounded among those with multiple marginalized identities (Center for Disease Control & Prevention, 2023; Everett et al., 2019; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine, 2021).

Some researchers have concluded that barriers to accessing high-quality maternity services lead to increased adverse pregnancy outcomes among these populations (Bacciaglia et al., 2023; McKinnon et al., 2016; McLemore et al., 2018). Others note that racialized and marginalized populations experience a disproportionate amount of mistreatment and lack of responsiveness when they do engage with perinatal services, and that in turn reduces both uptake of services and timely diagnosis and treatment (Bohren et al., 2019; Kemet et al., 2022; Vedam, Stoll, Taiwo, et al., 2019). Perinatal health outcomes among racialized people are inextricable from structural racism (Godley, 2018; Karvonen et al., 2023). However, few validated metrics, instruments, and measures capture information that is specific to experiences of perinatal care among these populations.

Community-Based Participatory Action Research and Health Equity

Community-based participatory action research (CPAR) is an approach characterized by “equitably partnering researchers and those directly affected by and most knowledgeable of the local circumstances that impact their health” (Horowitz et al., 2009, p. 2633). Further, it is grounded in social research, feminist action research, and research justice frameworks (Israel et al., 2010; Jolivétte, 2015; Reid, 2004; Sandwick et al., 2018; Tinetti & Basch, 2013). CPAR builds trust by including representative members of the researched community in all stages of the research process (Black Women Scholars and the Research Working Group of the Black Mamas Matter Alliance, 2019; Demange et al., 2012; Israel et al., 1998; Phillips-Beck et al., 2019) and is thus well suited to explore the priorities of marginalized communities that have been underrepresented in research (Aldridge, 2016; Horowitz et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2018; Turin et al., 2021), particularly those who are often referred to as “harder to reach populations,” (Black Women Scholars and the Research Working Group of the Black Mamas Matter Alliance, 2019; Bonevski et al., 2014). Community members inform the design of the study and selection of measures and are active participants in data collection, interpretation, and dissemination of results (Horowitz et al., 2009). When examining drivers of health disparities, CPAR recognizes that lived experiences cannot be separated from social determinants of health (Black Women Scholars and the Research Working Group of the Black Mamas Matter Alliance, 2019).

Measurement of Wicked Problems in Perinatal Services

In recent years there has been increased attention to patient experience as a core component of quality of care (Doyle et al., 2013; Manary et al., 2013; Valaitis et al., 2020). Because patient experience is inextricable from complex and varying healthcare environments, including systemic racism and health human resources, it is a “wicked problems” to investigate. The concept of “wicked problems” applies to many complex real-world issues that involve multiple interacting systems and uncertainties. The sources of “wicked problems” are often contested, they resist conventional resolutions, and are typically non-linear, iterative, or circular — thereby reinforcing themselves (V. A. Brown et al., 2010; Burman et al., 2018; Sharts-Hopko, 2013). Bradbury and Vehrencamp (2014) suggested breaking these cycles of dysfunction by understanding the interplays and system-level deficits in order to develop effective interventions. Changing these systems requires mechanisms for exposing, understanding, and altering the hidden dynamics between the players (Coleman et al., 2007). This is especially germane when seeking to improve maternal and newborn well-being within the context of divergent priorities of communities and providers, and health systems barriers to access and/or equitable care.

Previous Studies on Perinatal Experiences in Canada

In 2006, the Public Health Agency of Canada disseminated the Maternity Experience Survey (MES), a national study that examined care experiences, perceptions, knowledge, and practices during pregnancy and childbirth in a large representative sample of 6,421 women ages 15 years and older who had a singleton live birth in the 5–14 months before data collection (Chalmers et al., 2008). Of more than 300 items assessing social factors, perinatal health outcomes, and process of care, a few items assessed patient satisfaction with their experience of respectful care, dignity, and involvement in decision-making. The study sought to understand experiences of younger mothers (15–19 years), recent immigrant mothers, and First Nations, Inuit, and Métis mothers, noting that these populations experience multiple challenges that place them at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Notably, in 2006, validated person-centered measures of respect and disrespect were not available. Hence, MES metrics and analyses focus on population differences in rates of smoking, alcohol use, folic acid use, intimate partner violence, postpartum depression symptoms, and newborn care practices rather than the characteristics of interactions with providers and healthcare systems (Kingston et al., 2011). In addition, the MES pilot phase tested the feasibility and acceptability of the survey, but service users did not participate in study design, item selection, or content validation (Kingston et al., 2011).

In the past decade, some regional studies have used CPAR approaches to examine perinatal care experiences. Varcoe et al. (2013) conducted a qualitative study examining the perinatal care experiences and outcomes of 100 Indigenous women in Canada and found that participants commonly described distressing experiences during pregnancy and birthing, including lack of choice, racism, and economic challenges. In 2014, the Association for Safe Alternatives in Childbirth published a report in collaboration with the Maternity Care Consumers of Alberta Network, reporting the results of consultations, interviews, and focus groups with service users, clinicians, and community health workers (De Jonge et al., 2014). Respondents identified a lack of respect for patient autonomy; rude and inappropriate behaviors by physicians and other caregivers; lack of choice and informed consent; lack of quality of care; and negative attitudes toward marginalized populations as “burning maternity care issues.”

The Changing Childbirth in British Columbia (CCinBC) project explored preferences for, access to, and experience of, care by collecting survey data on 3,400 pregnancies in a representative geographic and socioeconomic sample (N=2051) (Vedam, Stoll, McRae, et al., 2019). Immigrants, refugees, and people with a history of incarceration and/or low socio-economic status reported significantly reduced levels of autonomy and respect, and non-consented procedures (Vedam, Stoll, McRae, et al., 2019). Experiences of respectful care also differed significantly by variations in access to different models of maternity care and/or place of birth. The CCinBC survey instrument was adapted to the U.S. context in the Giving Voice to Mothers study (GVtM) (Vedam, Stoll, Taiwo, et al., 2019) to examine experiences of perinatal services among racialized service users and those who planned to give birth in the community (homes or birth centers). The Community Steering Council for that study designed and added new items to measure racial and cultural identity, mistreatment, and non-consented care. Disparities in experiences of perinatal care and outcomes have been reported by Indigenous people in some Canadian provincial reports (Bacciaglia et al., 2023; Turpel-Lafond, 2020; Varcoe et al., 2013). However, to date, no Canadian national study has used patient-designed measures to examine the prevalence and characteristics of respectful perinatal care, particularly among diverse and under-represented populations.

In response to a dearth of patient-oriented research and measurement in perinatal services, the RESPCCT study (Research Examining the Stories of Pregnancy and Childbearing in Canada Today), used a CPAR approach to examine the lived experience of care during pregnancy and childbirth across Canada. This is the first Canadian study that focuses on pregnancy, childbirth, and perinatal health equity to have the robust engagement of community leaders, identity-matched scholars, and service users during study design, selection of study measures, and recruitment activities. In this paper, we describe how our multistakeholder study team — co-led by community members with lived experience — co-created and distributed a person-centered survey instrument that measures experiences of respect, disrespect, and mistreatment during pregnancy-related care among service users with diverse personal identities, circumstances, and backgrounds. We describe and evaluate our intentional approaches to highlight best practices for instrument development in reproductive justice research while illuminating lessons learned and challenges faced in participatory research.

Methods

Transdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder engagement

The RESPCCT study is co-led by a representative Community Steering Council (CSC) and a group of academic and clinician investigators. Recruitment for the CSC was intentionally inclusive of individuals with diverse and intersectional identities and circumstances. The governance structure and team commitments were designed to ensure that all decisions related to study topics, design, study measure selection, recruitment, data collection, and analysis procedures center historically marginalized persons. At the onset of the study in 2018, study co-investigators, community partners, and previous patient partners nominated potential Community Steering Council members across a wide range of lived experiences and perspectives. The final selection of CSC members from 10 provinces/territories ensured representation and lived experience of pregnancy as a person who is Indigenous, Black, Asian, Latinx, and/or identifies as 2SLGBTQIA+, and/or an immigrant or refugee. CSC members also had lived experience with disability, incarceration, living in a rural/remote location, and/or experiencing housing or financial instability. We also deliberately included clinician researchers from different perinatal professions (midwifery, obstetrics, family medicine, nursing), Indigenous researchers, sociologists, epidemiologists, policymakers, non-governmental perinatal services and advocacy organizations and human rights experts.

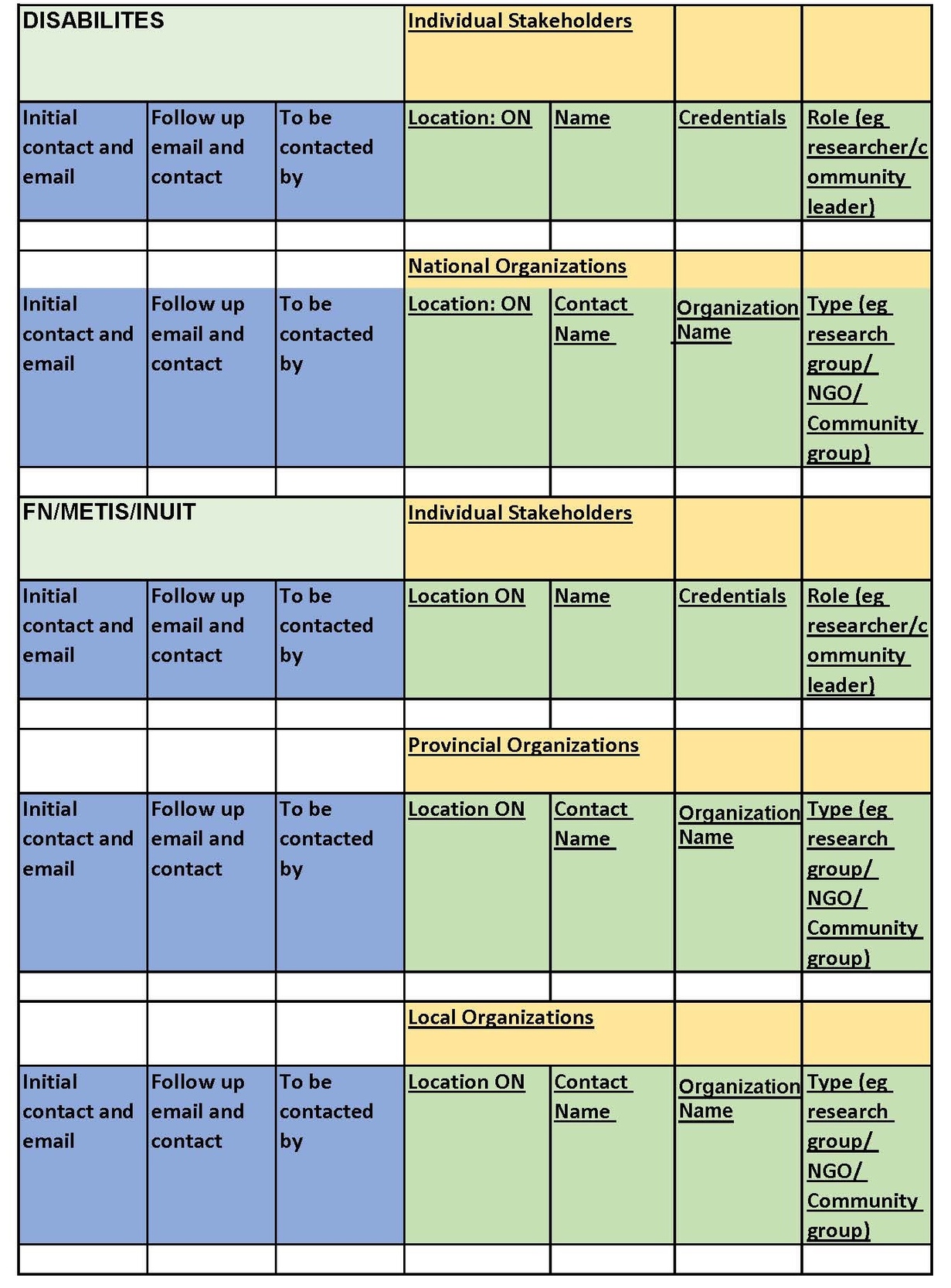

Two Community Engagement Coordinators (CEC) at the Birth Place Lab compiled a database of contacts and potential study champions in national, provincial, and local non-governmental organizations (NGOs), community health workers, population-specific clinics, community leaders and Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers, who had the potential to serve as collaborators and community partners. During the survey development and recruitment phases, all study team members were kept informed of study-related decisions and provided feedback via quarterly full-team meetings. The Principal Investigator, CECs, and Research Coordinators held bimonthly consultations with the Community Steering Council, established regular communications, and created accessible websites to house study resources and training materials.

The RESPCCT study received ethical approval from the following regional health authorities: Interior Health, Northern Health, and Island Health of BC; Newfoundland and Labrador Health Research Ethics Board; Labrador-Grenfell Health, Aurora Research Institute of the Northwest Territories, and the Yukon as well as the University of Saskatchewan and UBC Behavioral Research Ethics Boards.

Item generation – Measurement of respectful care during pregnancy and childbirth

Survey development involved a complex process including item generation, content validation and prioritization of study topics.

Desk and systematic review

We began by identifying the most important items for inclusion in a person-centered survey on respectful perinatal care in Canada. Bohren and colleagues (2015) developed an evidence-based typology of mistreatment in maternity care based on studies in low-resource countries. They described the phenomena across seven domains: 1) physical abuse; 2) sexual abuse; 3) verbal abuse; 4) stigma and discrimination; 5) failure to meet professional standards of care; 6) poor rapport between women and providers; and 7) health system conditions and constraints (Bohren et al., 2015). Their seminal paper called for the development and application of measurement tools to assess the prevalence of disrespect and abuse in maternity care.

Because there was minimal precedent and no item bank to inform a comprehensive investigation on respectful perinatal care in high-resource countries, we utilized a modified desk review and Delphi process to identify both the range of domains and a set of relevant, patient-designed items to evaluate for inclusion. Desk reviews are done to assess the quality of facility-level health data (World Health Organization, 2020) or to better understand health system issues where standard or consistent metrics for quality assessment of health services are not available (USAID, 2016). The Delphi method is a process of gathering feedback from a panel of experts over several rounds to determine panel consensus on a given topic (Boulkedid et al., 2011).

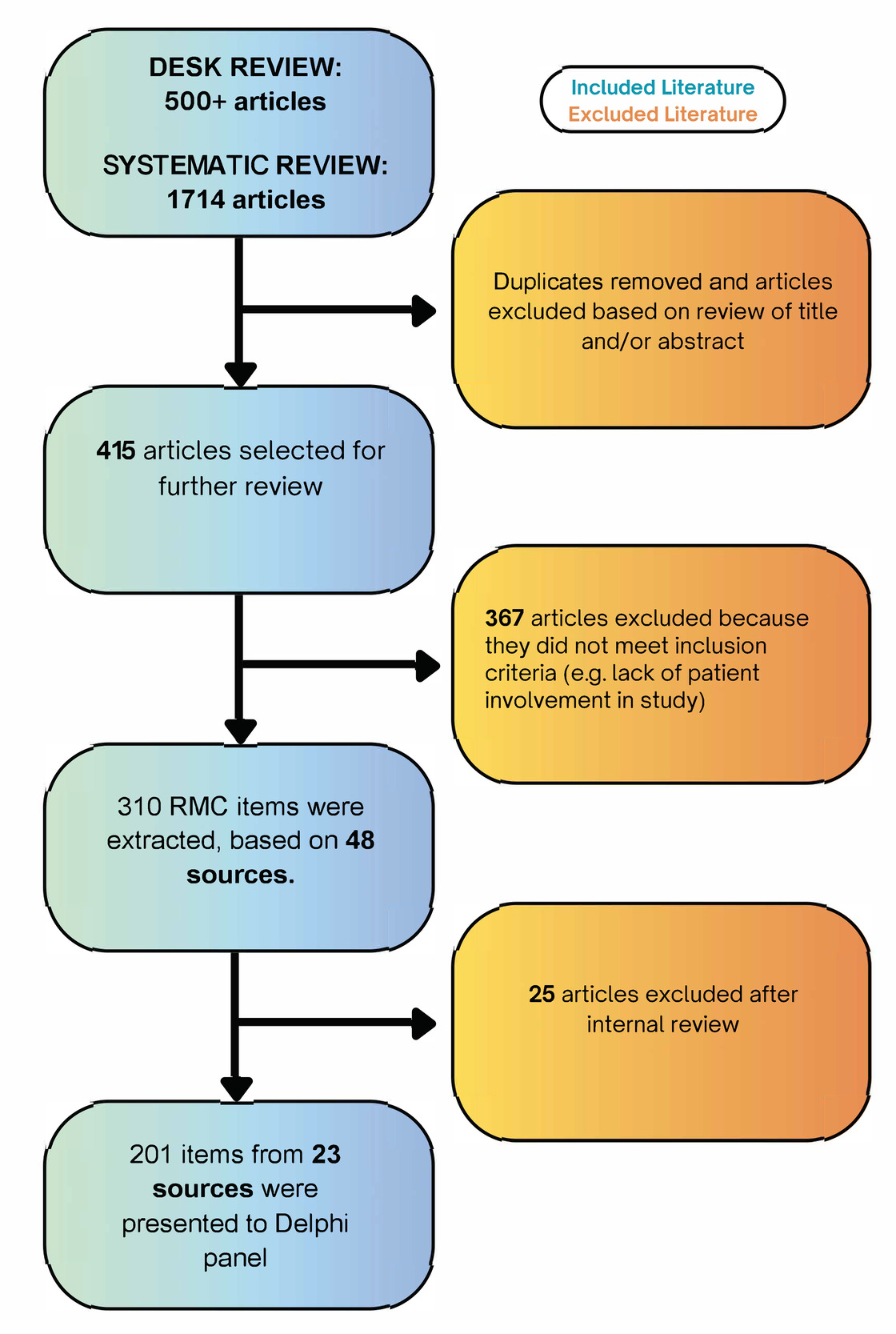

We searched titles and abstracts from databases including PubMed, Medline (OVID), PsychInfo, Google Scholar/UBC library, and Cinahl using the keywords: respect or mistreatment or disrespect or abuse + measure or tool or assess or instrument and labor, birth, delivery, maternity care, respectful maternity care. We utilized citation chaining by sourcing references in the articles that matched our criteria. This search strategy yielded more than 500 records. Finally, we searched the reference lists of systematic reviews of respectful maternity care (RMC) measurement tools and incorporated articles sent to us by experts in RMC measurement. We also performed citation chaining based on titles and abstracts of 331 articles that cited Bohren et al., (2015).

We selected articles from high- and middle-resource countries that reported on quantitative survey items. When domain-specific survey items were unavailable, we included items that had been used as question prompts by investigators in qualitative studies. We only included studies with evidence that patients were involved in generating items or items were developed based on patient narratives. We also considered or included items that assess pregnancy and birth outcomes, interventions, and patient-provider relationships from the MES Survey, several items and scales from the CCinBC and the Giving Voice to Mothers studies, and community-specific items designed by content validators from the under-represented communities.

Simultaneously, one of the co-authors conducted a systematic review using two databases (Medline (Ovid) and CINAHL), to identify articles that described the development or use of tools to measure respect and patient experience of perinatal care in high-resource countries. The review methods, including the search strategy are described elsewhere (Clark, 2019). The outcome of our combined desk and systematic review was 48 articles with demonstrated patient involvement yielding 310 distinct items.

Finally, we sorted items by themes of mistreatment identified in Bohren and colleagues’ (2015) typology and mapped them to the WHO Standards for Improving Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care (World Health Organization, 2016) which highlight eight standards of care and 31 quality standards for redress, including provision of emotional support; informed decision-making; responsive, motivated healthcare personnel; the rights to privacy, reliable information, choices for care; and freedom from mistreatment (Tunçalp et al., 2015). After the mapping of validated items was complete, we realized there were several subdomains or themes in the Bohren typology that were not captured. We then prioritized a targeted search of validated items and scales based on missing topics, e.g., painful vaginal exams, discrimination based on identity, or skilled attendant absent at time of birth. Because these searches were not fruitful, we consulted with service users and clinicians on our team to design new items. Our team met several times using a consensus-based approach to reduce the pool of 310 items to 201 items to be presented to a Delphi panel (see Figure 1). We removed items with duplicate intent, unclear or vague wording, and items that did not measure experience of care.

Delphi process for expert content validation

The Delphi method has been used to develop healthcare quality indicators (Boulkedid et al., 2011) and patient surveys (Li et al., 2016). The RESPCCT Delphi Expert Panel included stakeholders who were care recipients; community advocates and human rights lawyers; healthcare system administrators; healthcare providers; and researchers who had experience with investigating respectful maternity care, healthcare experiences among historically marginalized populations, and/or the development of measurement tools. In the context of the RESPCCT study, the Delphi panel provided anonymous feedback on respectful care measures over two rounds via an online survey platform. In round one (n=20 participants), the multidisciplinary panelists rated each item on four-point ordinal scales for their importance to the concept of RMC, relevance to a diversity of communities and practice contexts, and their clarity. In round two (n=26 participants), panelists were presented with the items sorted by domains as described by Bohren (2015) and by the CSC to reflect characteristics of mistreatment and disrespect, as well as respectful, optimal, and kind supportive care. Panel members ranked items within each domain from least priority to highest priority for inclusion in a Canadian survey on RMC. After both rounds, the list of 201 items was reduced to 156. The list of indicators could not be reduced further because of high relevance ratings for most of the items and positive evaluations of the 112 items that were revised based on round one feedback or merged with similar items to furher reduce duplication. A full description of the Delphi process and findings is published elsewhere (Clark et al., 2022).

Socio-demographic and health systems measures

Two doctoral students gathered relevant socio-demographic variables that were phrased to facilitate respectful, inclusive, and trauma-informed assessment of multiple identities and circumstances (Salkind, 2010). To be inclusive of historically marginalized and underserved communities, our initial search for validated and respectfully phrased socio-demographic items included the following categories: race, ethnicity and language, sexual and gender identity, socioeconomic status, perceived health, food and housing insecurity, social support, health related social needs and life events (Braveman et al., 2005; Canadian Institute of Health Information, 2015; Duncan et al., 2002; ICHOM, 2017; Institute of Medicine, 2014; Statistics Canada, 2023; Tsemberis et al., 2007). We included items that collected information on respondents’ identities, living situations, health-seeking behavior, health status, and environment.

After items were identified, they were reviewed by the Community Steering Council in online meetings to ensure that they were meaningful and relevant. While consistent variables are needed to collect data that is comparable across populations, the variables also need to describe the systemic disadvantages and risks incurred by specific marginalized groups. Grounding the survey development in CPAR required integrating group-specific descriptions of race, ethnicity, income, etc., while also collecting population-level data in a way that can impact policy. For example, ethnicity is highly context specific as a predictor of an individual’s risk for health outcomes and access to care (Braveman et al., 2005). Also, people with low socioeconomic status who engage in CPAR research note that traditional metrics, such as household income, alone are less illustrative than household income plus household size, and less discriminating than items that capture consequences of economic disadvantage such as “lights were turned off at the end of the month,” “I did not have enough food by the end of the month,” “I could not pay my bills,” or “I needed public subsidies for food or housing” (Stoll et al., 2022). The Community Steering Council also suggested some rephrasing to enhance inclusiveness, clarifications to answer options (e.g., participants could select more than one identity), and approved the final set of items. When the CSC identified items that could trigger unwanted or harmful memories, we co-designed preface language to introduce the item sets, provide rationale for the questions, provide a list of free counselling services, and allow participants to skip questions.

Final Survey Construction

Following the Delphi process, the CSC vetted, revised, and approved a set of 210 items that were deemed relevant to the measurement of respectful perinatal care in Canada. While the CSC mostly agreed with inclusion of the top 50% of items that had achieved high consensus, they identified some key domains and items that were particularly germane to their communities’ lived experience despite being below 50% consensus. These items included experiences of forced sterilization or fundal pressure during labor. The final instrument includes validated patient-designed outcome measures that assess experiences of respect, disrespect, stigma, discrimination, mistreatment, and health systems factors that are particularly resonant with marginalized populations.

Our team mounted the final set of 388 items (including eligibility, sociodemographic, and respectful care measures) onto an online survey platform (Qualtrics). To increase accessibility, we identified individuals qualified in medical translation to formally translate the English language tool into seven languages that are spoken by the largest minority populations in Canada (i.e., French, Inuktitut, Chinese, Simplified Chinese, Arabic, Spanish, and Punjabi). Each translation was then checked by a second translator and inconsistencies or errors were discussed and corrected. To support transparency and increased measurement consistency across high- and middle-resource countries, all items and adaptations recommended for Canadian use by the CSC are publicly available in an online RMC Measurement Registry at https://www.birthplacelab.org/rmc-registry/ (Clark et al., 2022). The co-investigator team, CSC members Regional Recruitment Coordinators, and multi-disciplinary trainees with lived expertise beta-tested the online-survey tool. To enhance accessibility and inclusion, we also created a screen reader version of the survey as well as a separate survey pathway for those who had experienced a pregnancy loss.

Branding

The study name, logo, and poster and social media images (see Figure 2), and dedicated study website were co-designed and approved through a four-month consultation process of multiple consultations (via online meetings and surveys) with the study team and CSC. Collective goals were to maximize inclusivity, simplicity, transparency, and accessibility. A graphic designer with lived experience created images that emphasized inclusivity, representing service users with a range of identities and circumstances. The study website used lay language to describe study goals, the participatory process for study design, and displayed names, photos, and biographies for co-investigators, CSC members, and Regional Recruitment Coordinators (RRCs).

Pilot Testing

The CECs, co-investigators, and CSC nominated and confirmed a purposeful group of 60 people with lived experience from across Canada, including recent immigrants, people with disabilities, Indigenous individuals, racialized people, people living in rural areas, and sexual and gender minoritized individuals, to pilot test the online survey in January 2020. The diversity of these pilot testers was reflected in their self-identified characteristics, including age, race, ethnicity and cultural heritage, religious beliefs, appearance, the wearing of cultural, heritage or faith symbols, gender and sexual identities, partner status, educational background, socioeconomic status, residing province, pre-existing medical conditions, and disability(ies). They were tasked with reviewing the survey content, navigability, and relevance of items. Feedback about survey length, structure, functionality of the online tool, and clarity of questions was integrated to ensure the final survey instrument was community-responsive, user-friendly, and relevant to diverse lived experiences. Team members took several weeks to review and discuss every piece of feedback. The team then reworded or added questions and response options, as requested by pilot testers. For example, the response option “not applicable” was added to questions where a pilot tester felt that none of the options represented their experience. Many pilot testers found the survey too long at an estimated 40-60 minutes to complete all items. Subsequently, the addition of new questions was accompanied by deletions elsewhere. The tool was also intensively beta-tested by research team members, especially survey pathways that might not have been completed by pilot testers. For example, we asked research team members to complete the survey from the perspective of childbearing people who gave birth to twins, experienced a loss, and had many healthcare providers involved in care.

Community Engagement Coordinators

To recruit a national sample, while item generation and survey construction was underway, two CECs carefully curated a matrix of more than 1,000 individual and organizational contacts. They worked with trainees and used social networking, referrals from the CSC, collaborators from national and health professional associations, and research groups at Canadian National Institute for the Blind and the Centre for Gender & Sexual Health Equity as well as internet searches to identify other community-based organizations across Canada. They prioritized organizations that serve under-represented communities, including Indigenous people (First Nations, Métis, Inuit), racialized, sexual and gender minoritized populations, recent immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers, and people with disabilities, those with history of substance use, incarceration, housing instability, and/or people living in rural or remote areas They joined or requested permission from parenting groups, perinatal care advocacy groups, government members, and experts in maternity care research or leadership to engage these populations. Whenever possible, the CECs sought out study champions at population-specific NGOs and agencies. The CECs and trainees used email or phone to request study champions’ assistance with distributing surveys to community members who access their services. They documented a description of their service or role and preferred method of distributing the survey (See Figure 3). Once the survey was ready for distribution, the Community Engagement Coordinators helped identify regional community members who could encourage survey participation.

Regional Recruitment Coordinators

Networking strategies were also used to identify local community leaders in various provinces willing to serve as Regional Recruitment Coordinators (RRCs). Similar to the representation we sought for the Community Steering Council, the engagement process included an interview and vetting process to prioritize those who had wide networks and established communication channels with local families; had personal lived experiences of perinatal services; and had the trust and confidence of local marginalized communities. RRCs completed formal research ethics certification; attended orientation and training sessions on how to maintain confidentiality, minimize power dynamics, and maximize transparency and inclusivity; and signed a community agreement to those principles (see Supplemental File S1). To ensure consistent descriptions of the study were used and to reduce the burden, the CECs provided each RRC a province-specific contact list template, phone and email scripts describing the goals of the study (see S2, S3), and social media content. RRCs were invited to quarterly meetings and encouraged to participate in knowledge translation. Each RRC was assigned one of the CECs, who was available to provide population-specific recruitment materials, answer queries, and support them in all activities.

Recruitment Modification

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated a change to our recruitment strategy. We had planned to engage a variety of data collection methods, including in-person survey “cafes,” focus groups, and recruitment events. We had hoped to reach those who required support (e.g., a translator or borrowed device) to participate, as well as those without reliable internet access (including many rural, remote, and Indigenous communities). When data collection moved completely online, we had to adjust our expectations and recruitment methods. In addition to the global pandemic, the increased exposure of anti-Black, anti-Asian, and anti-Indigenous systemic racism affected participants’ capacity for engagement. Our team members conveyed that the barrage of these events and discourses was exhausting and traumatizing to communities with lived experience of racism and oppression. However, community partners also urged us to keep the survey open to allow those most affected more time to participate. Hence, we decided to offer a shorter, core data survey version. Five co-investigators and staff team members reviewed survey items and collaboratively decided on which items to retain for the short version, primarily removing explanatory details and follow-up questions, and proposed a core set of items for CSC approval. The process resulted in a core survey tool that took half the time to complete but retained at least one or two items that captured information in each domain. This version included 271 items and was offered in the final six months of data collection.

Results

The RESPCCT core study team includes a Steering Council of 10 service users from underserved and understudied communities; a 10-member multi-disciplinary panel of co-investigators; 30 community-specific NGO leaders and knowledge users (e.g. BC Ministry of Health, Unlocking the Gates, National Aboriginal Council of Midwives); and 18 Regional Recruitment Coordinators.

The final survey instrument was comprised of 210 items that measure respectful care across 17 domains (Clark et al., 2022), as well as sections that capture information about participants’ identities, circumstances and backgrounds, access to care, provider type, and maternal and newborn outcomes. Additionally, the instrument included previously validated measures, such as a discrimination index (Scheim & Bauer, 2019), a scale that identifies symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder related to childbirth (Ayers et al., 2018), and three person-centered measures of autonomy, respect, and mistreatment previously developed by our team (Vedam, Stoll, Martin, et al., 2017; Vedam, Stoll, McRae, et al., 2019; Vedam, Stoll, Rubashkin, et al., 2017; Vedam, Stoll, Taiwo, et al., 2019).

Community Engagement Evaluation

To understand ongoing experiences among our large and diverse team, we adapted the Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool (PPEET) (McMaster University, 2018) and, twice during the project, distributed the adapted survey (see S4) to all team members. Feedback was overwhelmingly positive, with respondents highlighting the strong culture of respect and inclusion, a sense of support and solidarity, and openness to sharing and incorporating different perspectives (see Figure 4). One respondent commented, “the inclusive and collaborative approach did not feel like just a checkbox to meet funding criteria but rather resonated as a true value held by those involved.” Respondents also expressed satisfaction with their level of engagement and perceived impact; for participants without an extensive background in academia, the ability to contribute personal experiences was noted as particularly empowering. Many members also appreciated the knowledge they gained about CPAR methodology and found it a meaningful way to conduct research.

When reporting about ways to improve their experiences, respondents expressed desire for more training around cultural safety and research processes, as well as increased networking opportunities between regional groups to overcome potential feelings of disconnection. Most respondents strongly believed their views could be freely expressed and were respected; however, others wished for more “willingness to see things from different viewpoints” and "opportunities to speak for [their] community and [their] region."Some respondents also felt that additional compensation, (e.g., for the Delphi process), would be appreciated given the high level of commitment.

Survey Distribution and Uptake

After translating the English survey into eight additional languages and creating a version optimized for screen readers, we launched the survey on July 1, 2020. To ensure robust participation of traditionally harder-to-reach populations, our original plan was to use evidence-based approaches such as peer recruiters, targeted sampling, venue-based sampling, oversampling, and network sampling via NGOs and community partners (Bonevski et al., 2014; Kalton, 2009; Merli et al., 2016; Peterson et al., 2008). However, to account for barriers to data collection caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, we extended the data collection period from 12 to 18 months, shortened the survey, and modified the recruitment plan to a fully remote process through social media and online networking.

Ultimately, 6,096 individuals across Canada who had experienced pregnancy and/or birth in the ten years before data collection participated in the RESPCCT Study. Only two eligibility items were mandatory and all respondents could skip questions; yet, 3,581 people (58.7 %) completed all items on the survey, with 1,660 participants completing respect measures related to the experience of autonomy more than once. Respondents had the option of reporting on a previous (n=5840) or current (n=256) pregnancy experience. Those who reported a loss (n=349) in a previous or current pregnancy could select which sections of the survey to complete. Of the 223 who experienced a miscarriage or abortion, most (n=217) agreed to answer questions about their experience and six did not want to share details. Of the 126 respondents who experienced a second-trimester stillbirth or neonatal loss, 108 agreed to answer all questions, nine elected not to answer postpartum or newborn questions, and eight chose not answer questions about labor, birth, and the postpartum and newborn period. Only one person with a late loss elected not to answer any of the survey sections. One in three respondents identified as belonging to a historically-marginalized group, including those who self-identified as Indigenous (n=318), racialized (Black, Latinx, East Asian, South Asian, Middle Eastern) (n=826), non-binary or other gender minoritized person (n=70), 2SLGBTIA+ (n=672), recent immigrants and refugees (n=217), having a disability (n=383) and/or being affected by substance use during pregnancy (n=402), having difficulties with meeting financial obligations (n=367), or reporting that they or their partner had a history of incarceration (n=29). Many respondents identified with more than one marginalized group. The survey was offered in eight languages; English had the highest participation (n=5,421), followed by French (n=549), Arabic (n=60), Traditional Chinese (n=27), Simplified Chinese (n=15), Spanish (n=17), and Punjabi (n=7).

Measurement of respectful perinatal care

Preliminary analysis shows that our CPAR-designed survey with novel measures successfully captured disparities in experiences of mistreatment and quality care across populations. The majority of respondents completed scale items measuring autonomy and respect and reported on type of perinatal care provider, mode of delivery, and place of birth. Respondents detailed personalized, exceptional care as well as discrimination, disrespect, and/or mistreatment; and 2,741 people described “one thing they would change” about their care in open-ended comments.

As a result, we are able to report on similar trends in findings as our previous work (Vedam, Stoll, Martin, et al., 2017; Vedam, Stoll, McRae, et al., 2019; Vedam, Stoll, Rubashkin, et al., 2017; Vedam, Stoll, Taiwo, et al., 2019) including lack of clinician competencies to support person-centered decision-making, anti-oppressive, and trauma-informed care; inconsistent health system responsiveness; and unmet needs for accountability. Participants stressed the importance of sharing their stories and implementing existing community-responsive solutions without delay (Vedam, Malhotra, et al., 2022a, 2022b; Vedam, Titoria, et al., 2022). Disrespectful care, violations of autonomy, and inequitable access to health services are recognized by the WHO Research Group on Respectful Maternity Care as types of mistreatment that represent human rights violations (Khosla et al., 2016). Canadians who have unexpected interventions report significantly more mistreatment by health care providers (Vedam, Malhotra, et al., 2022b; Vedam, Stoll, Taiwo, et al., 2019) and rates of obstetric interventions are higher in racialized and marginalized populations (Davis, 2019; Logan et al., 2022). Notably, rates of obstetric interventions across Canada do not achieve the WHO standards for quality maternity care. The national Cesarean rate of 32% (Canadian Institute of Health Information, 2015) exceeds the WHO global recommendations that note that rates of surgical birth greater 10–15% offer no benefit in outcomes (The Lancet, 2018).

Discussion

We applied best practices in CPAR to co-create a person-centered survey instrument that measures the lived experience of care during pregnancy and childbirth, and perinatal health equity, across Canada. We intentionally centered the priorities of service users in our governance model where a representative CSC had the decision-making and veto power over study design, measures, and data collection procedures. We took the time needed for authentic and iterative consultations with community members. We provided trusted supports during recruitment through CECs, and RRCs, culture-matched trainees, as well as population-specific community health workers. As a result, we were able to recruit a large and diverse national sample despite data collection during challenging times.

Strengths: Relevance, Uptake and Accessibility

First, our RESPCCT study has been informed and led by communities that have historically been absent during the design of knowledge-producing activities, such as research, due to discriminatory pre-conceptions. According to Fricker (2007), this systematic exclusion represents a form of epistemic injustice, namely testimonial injustice, which captures the idea that a person is wronged specifically in their capacity as a knower. Conversely, our CPAR approach represents a means to contribute to restoring testimonial justice to epistemically dismissed populations.

Second, Moss and colleagues (2017) depicted the life cycle for patient and public involvement that aligns with the process we have codified. In the RESPCCT study, service users decided what to study, the key domains to measure, helped to identify, vet, adapt, and/or design the measures to use, and determined the best data collection methods that resonate with their communities (See Figure 5). They also helped to refine the terminology and wording used throughout the survey and recruitment process to enhance inclusion and to minimize feelings of bias or judgement. Through this process, we successfully co-developed an online, cross-sectional survey that describes the lived experience of perinatal service use, and assesses health systems adherence to and violations of respectful maternity care (RMC), as defined by the WHO and the Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (IAWG, 2018; Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, n.d.; United Nations General Assembly, 2019; World Health Organization, 2016).

Third, we responded to a call to ask different research questions that re-prioritize research in maternal and newborn health towards “quality care that is tailored to individuals, weighs benefits and harms, is person-centered, works across the whole continuum of care, advances equity, and is informed by evidence” (Kennedy et al., 2016, p. 222). Despite multiple humanitarian crises during study recruitment (2020–2021), there was robust engagement from marginalized groups and all Canadian provinces and territories.

Respectful Engagement of a Multi-Stakeholder Team

The RESPCCT study team members and Community Steering Council have provided expertise from the lived experience of multiple and intersecting identities including being First Nation, Inuit, and Métis, racialized, of minority sexual and gender identities, migrant communities, non-dominant cultural groups or body types, and/or disabled. At times, engagement was labor-intensive with many stakeholders to consult at each step. However, perinatal care is a time when many individuals and communities experience unaddressed harm (Altman et al., 2023; Shaheen-Hussain et al., 2023). The intentional inclusion of research participants in a process of inquiry values the dignity and autonomy of the individuals most affected (Roberts, 2013) and disrupts typical research practices (Jolivétte, 2015) while addressing power dynamics that are often implicit between researchers and researched communities (Reid, 2004). New modes of organizing decision structures and workflow via CPAR (see S5, RESPCCT Org Chart) can offer a first step in repairing centuries of harm and begin to dismantle the false dichotomy of expert versus research subject.

We enlisted a large team of Regional Recruitment Coordinators (RRC) responsible for disseminating the survey to different communities based on their interest in the project and geographical region (see S6, RRC Job description). As we did not have RRC representation from every sociodemographic community we wished to engage, duties were primarily divided by geographic region. In hindsight, RRCs’ expertise may have been better utilized through a different structure. For example, a combination of recruiting participants who shared their identities (e.g., language, cultural or racial community, or lived experience) across Canada, as well as general recruitment in their province or territory.

Delays in communication between the core team and CSC/RRC members related to staffing changes or leaves, and/or delays in payment of honoraria due to institutional processes that were not nimble, were sometimes viewed as exclusion from the work or evidence of disrespect for their efforts. Fortunately, over the years of project, we grew to understand each other’s contexts, make room for these conversations and feedback, and adjusted both our processes and mutual expectations.

We also received feedback from some community-centered organizations (CCO) that they were not sufficiently engaged at the start of the research process. For example, shortly after the survey was launched, we heard from a surrogate pregnancy advocacy organization lamenting the exclusion of a pathway for gestational surrogates. Our team discussed the possibility of adding such a pathway but ultimately decided against it because the survey development process did not include item development for gestational surrogates. The exclusion of surrogate parents will be noted as a limitation in future publications of results.

While we conducted a national scan to identify these CCOs and developed phone and email scripts to identify study champions in each region, we did not have capacity to follow up systematically prior to engaging the RRCs. As a result, some CCOs were not invested in the study and not engaged in recruitment efforts. Relying on referrals from individuals rather than obtaining early buy-in from CCOs may have hampered our efforts to connect with certain communities. In future studies, we would appoint RRCs earlier in the process to assist with fostering these important relationships.

The CPAR model may serve as a way to mitigate the biases of any one researcher by incorporating many different viewpoints and centering the voices and perspectives of those most affected by the research topic. A critical component of CPAR is for research teams to learn the complex history between researched communities and researchers. Mistrust of research and the people and institutions is particularly marked for Indigenous people in Canada (Schnarch, 2004). An understanding of history can provide insight into how and why certain disparities exist and protect against replicating them. For example, our decision to offer a shorter, core data version of the survey was widely endorsed by the CSC and RRCs as a reduction of burden and demonstration of respect for the collective trauma of the moment. It was critical to recognize, acknowledge, and unlearn our biases and how researchers arguably have more power in interactions with community members and can be complicit in racism, discrimination, and oppression through our research.

Survey Co-Design

Respecting a participatory process for survey construction takes time. To ensure a respectful and inclusive process, multiple cycles of consultation with stakeholders are necessary to offer many opportunities to be heard. By using a Delphi method to select and prioritize measures, we met our goal to draw on a diversity of voices and communities. The Delphi method is designed to gather feedback anonymously in a way that allows all feedback to be considered with the same significance and prevents domination of group opinion by influential panel members (Keeney et al., 2010). When forming the expert panel, we carefully recruited a range of stakeholders and expertise. A heterogenous approach to forming a Delphi panel has been described as increasing the validity of the consensus (Boulkedid et al., 2011) and invites a broader range of opinion and experience to be shared (Trevelyan & Robinson, 2015). The online format rather than in-person or virtual meetings was chosen to accommodate Delphi participants in different time zones and to avoid the dominance of more vocal participants in the item selection process. CSC members noted that by participating in the Delphi process with both input and veto power, we adhered to our stated commitment to community-led design, which was experienced as both unusual and empowering.

As a result of listening to service users at every step of the survey development process, we added more items than we were deleting. The result was a very long survey with the potential to overwhelm and reduce participation. Nonetheless, through these multiple rounds of consultation and expansion of items, both the phrasing and prioritization of items were modified to produce a final instrument that resonated with — and was responsive to — the priorities of communities that have been underrepresented in traditional research instruments.

We incorporated input from various stakeholders who were without traditional research experience, leading to the inclusion of items that were phrased in nontraditional ways. This may have contributed to the tremendous amount of data cleaning and coding that was required. However, the high level of participation by non-traditional researchers and community members may have been boosted by their ability to share in their own words as opposed to only through pre-selected response options. In future surveys we might offer more drop-down options for variables like height and weight but retain the ability for people to self-identify more complex concepts like racial identity.

At times, there were tensions among team members on how to integrate community feedback. For example, team members with expertise in instrument development suggested using the same response options for all items measuring RMC to enable construction of a community-developed multidimensional tool for use in future studies. However, pilot testers and other team members suggested changing up the response options to avoid survey fatigue and to better align response options with question stems. The team had long discussions about such issues and compromised by balancing community and research perspectives during survey development.

Budgetary Constraints

In the RESPCCT Study, grant funding limitations meant that we could only offer small honoraria to collaborators over the full course of the project. These budgetary constraints meant that lab staff were responsible for project management as well as community engagement, and therefore did not always have the capacity to devote the time necessary to build relationships and support recruitment efforts in addition to their day-to-day responsibilities. This meant that RRCs were responsible for building trust with communities to recruit potential survey participants while simultaneously navigating complex, and sometimes conflicting, feelings of trust/mistrust with the academy and the research process. As a result of feedback from RRCs, office hours were implemented to create space for asking questions and building rapport amongst the team.

Our research budget included compensation for CSC members ($500-$1000/year depending on expected time commitment), pilot testers ($100/survey completed), RRCs ($350-700 depending on size of region or priority population), and Indigenous Elders ($300/hr) for their contributions. Community members appreciated receiving honoraria and acknowledgement for their contributions. Some noted this was a significant difference from other projects where their engagement was solely voluntary. However, the compensation was far less than we would choose to offer had we access to more funding. Often researchers and academics working on a study have a funded appointment (clinical, academic, etc.) and/or receive merit or promotion metrics that recognize them for the work they do on a project. Community partners, however, do not have such options; as such, compensation by way of honoraria is necessary to support their involvement in a more equitable way (Novak-Pavlic et al., 2023). Additionally, due to the unanticipated need for an extended data collection period, the honoraria provided to RRCs did not reflect equitable compensation for 18 months of recruitment work. Current funding models are generally not configured to account for the pace and scale of engagement, consultations, and collaboration necessary to build authentic trust and relationships through CPAR, and to avoid replicating inequitable precedents (Horowitz et al., 2009; Phillips-Beck et al., 2019; Reid, 2004; Turin et al., 2021).

Measuring the Wicked Problem of Mistreatment in Childbirth

When solutions are proposed by “external experts” and “imposed on communities,” they are often incongruent with the needs, priorities, and/or lived realities of the populations experiencing the adverse events (Campbell & Cornish, 2010). In 2017, in response to persistent global “wicked problem” (V. A. Brown et al., 2010; Burman et al., 2018) in the realm of reproductive health, the WHO published a Health and Human Rights report describing a transformative agenda based on the principles of equality, inclusiveness, non-discrimination, participation, and accountability (World Health Organization, 2017). The authors asserted that community participation must move beyond consultation to “continuing dialogue between duty-bearers and rights-holders about their concerns and demands. For policies and interventions to be fully responsive to their needs and consistent with their rights, they should be designed and monitored in partnership” (p. 43) with communities. They suggest that a deliberate, collaborative, multi-stakeholder process will expand and deepen the identification and descriptions of problems and thus strengthen the development of effective interventions beyond purely biomedical approaches. They also note that the authentic inclusion of diverse voices in an equitable decision-making process can reduce mistrust, foster solidarity, and “reduce gaps between policy intent and policy acceptance” (World Health Organization, 2017, p. 44). Strategic initiatives to address these wicked problems require the input and expertise of different disciplines, but ultimately must be feasible and resonant within community realities (V. A. Brown et al., 2010; Burman et al., 2018). This is why we committed to CPAR processes to examine disparities in perinatal health and inequities in experiences of care across marginalized communities.

Limitations

A survey instrument cannot capture all variations of human birthing experiences. When people reported their gender or sexual identity we may not have asked the right questions and, by not including the non-gestational parent as a potential participant, our ability to elicit a comprehensive picture of queer and trans families is limited. To address this limitation and gain a better understanding of the unique perinatal care and family-building experiences of gender and sexual minority individuals, we are supporting another multistakeholder team to create a survey study focused on queer and trans families. Data collection for the Birth Includes Us study (birthincludesus.org), developed with a LGBTQIA2S + specific CSC, is underway. Also, some large racialized groups in Canada, such as the South Asian community, were not well represented in the RESPCCT Study. Despite being the fourth most common language spoken in Canada, only a small number of participants chose to complete the survey in Punjabi (n=7); however, there are hundreds of languages and dialects spoken in the South Asian region.

In this paper, we use the term Indigenous to describe the three distinct groups recognized by the Canadian constitution: First Nation, Inuit, and Métis. Each of these groups have unique histories, policy implications/applications, and relationships to the Canadian government. There are more than 600 First Nations alone, which could have their own cultural or political differences. In addition, we are conscious that while we had input from Indigenous service users on the CSC, pilot testers, and RRCs and Indigenous researchers and Elders on the full study team and a survey version in Inuktitut, this survey instrument cannot capture the myriad contexts of pregnancy and childbirth care as experienced by members of different nations, nor honor their Indigenous ways of knowing or doing research, in a national project. In acknowledgment of this limitation, we collaborated with two Indigenous researchers on the RESPCCT Study team to conduct a parallel study to determine culturally responsive ways to measure lived experiences and factors associated with respect, disrespect, racism, implicit bias, and mistreatment in perinatal care in five Indigenous communities in Canada.

Finally, the unwieldy nature of such a large CPAR project required constant adaptation and flexibility. The level of community participation we undertook was enormous and ambitious compared to a typical study. At times it felt challenging to move through each step with so much feedback and expertise to integrate into the project. The process was a humbling reminder that despite the diverse voices informing the creation and dissemination of the survey, there were gaps that need to be addressed in future research. CPAR methods run contrary to the norm in academia; however, conducting research in a way that prioritizes community participation and relationship-building is essential for moving towards more ethical and just research practices.

CPAR’s implicit “by community, for community” ethos must not be diluted by the “enterprise of patient engagement” (Johannesen, 2018). Johannesen’s work on the topic cautions against virtue signaling in place of meaningful participation and provides a necessary critique of performative community engagement. Authentic CPAR is a goal to strive for, not a destination or a box to check off. We hope that describing the strengths and limitations of our RESPCCT Study will serve as a map to guide future projects forward.

Conclusion

It is crucial that in research focused on sentinel and intimate life events, such as pregnancy and birth, investigators lay a groundwork of trusting relationships, particularly when the research aims to capture the experiences of those who are underrepresented in research. Many of the community members who co-led the RESPCCT Study have experienced marginalization, oppression, and mistreatment not only within the healthcare system and society at large, but also from researchers. These harms make it even more important to take the time to build trust and foster a relationship that centers the community’s needs and safety over the research objectives.

To understand the experiences of pregnant people who have historically experienced exclusion from design of research about their communities, it is essential for service users to identify and inform measures of their own experiences, including structural racism (Crear-Perry et al., 2021), intersectional oppression (Dillaway & Brubaker, 2006; Scheim & Bauer, 2019), ableism, and social determinants of health (Government of Canada, 2020). This is both a medical and ethical imperative. Through our participatory methods for survey development, we successfully prioritized patient-centered measures and presented them in a way to enhance the psychosocial safety of participants. When communities gain their rightful place in knowledge-producing activities, we can begin to counter epistemic injustice (Fricker, 2007).

Acknowledgements

This paper would not have been possible without the long-term commitment and participation of members of the RESPCCT Community Steering Council and community and professional organizations involved in study design, recruitment, and pilot testing (including Unlocking the Gates, Canadian Association of Midwives, Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the National Indigenous Council of Midwives). We are grateful for the insight and support from senior researchers, policymakers, and methodology experts on the team (Janusz Kaczorowski; Wendy Norman; Karline Wilson-Mitchell; Vicki Van Wagner; Lori Brotto; Jan Christilaw; Raymonde Gagnon; Hamideh Bayrampour; Ruth Elwood Martin; Kellie Thiessen; Patricia Janssen; Wendy Hall; Sarah Munro; Glenys Webster; Cecilia Jevitt; and Tamil Kendall); Alison McLean for her contributions to item generation, environmental scans, expert community engagement, and countless hours of data management, including verification, cleaning, and coding; Dana Solomon, for her insight and acumen on subpopulation item design and knowledge translation; and all of the Delphi Expert Panel members. We would also like to thank Laura Beer, Jasmina Geldman, and Kate Benner for expert operational, fiduciary, and project management; Lynsey Hamilton, Jeanette McCulloch, Chanelle Varner, and Denice Cox for contributions to website development, communications, graphic design, branding, social media, and recruitment materials. Graduate and professional research assistants who supported RESPCCT survey and development of this manuscript were essential to publication: Jessie Wang, Samara Oscroft, Sabrina Afroz, Bhavya Reddy, Eyar Baraness, and Elise Everard. Most importantly, we are deeply indebted to the study participants who spent considerable time and energy to carefully and eloquently respond to the survey.