Introduction

We cannot truly engage in research that seeks to advance equity and social justice without ensuring that the process through which we engage in this research is imbued with these same principles of inclusion. As such, an essential component of equity-focused research is a methodology that centers marginalized voices within the research process and treats community partners as valued and respected collaborators with essential sources of knowledge and expertise.

When enacting equity and inclusion principles in the research process, a central consideration is how best to involve and elicit knowledge from practitioners and stakeholders outside the research team. It is essential to acknowledge that an inherent power imbalance exists between researchers and the communities they seek to investigate, tied up with histories of oppression that many groups, specifically racial minorities and low-income individuals, have experienced as a result of participation in research projects (Harrington et al., 2019). To mitigate the effects of these histories in current equity research, participants must be recognized for their contributions through equitable and meaningful compensation. For most research participants and community partners, financial compensation is one of the most impactful forms of recognition for the time and expertise that individuals have shared with researchers (although it is worth noting that in some cases, sharing academic accolades with community partners for whom such recognition would be relevant can be a meaningful way of acknowledging the depth of their knowledge and the centrality of their contributions) (Minkler, 2005). Equitable compensation that accounts for participants’ needs and abilities helps ensure that people from different financial backgrounds have equal opportunities to access and benefit from research participation. The following tutorial offers methodological instructions for one approach to equitable compensation via the introduction of RAND CAREP’s[1] Equity-Centered Participatory Compensation Model (EPCM). The EPCM recognizes that flexible payment options that prioritize the needs of the participants are essential when centering equity principles.

Within community-based participatory research (CBPR), there is an inherent contradiction in current participant compensation practices. When working with historically marginalized communities, it is essential to ensure that financial rewards for participation are robust, so as not to continue cycles of dispossession and unjust or unlivable wages for labor (Leroi et al., 2022). At the same time, it is essential to acknowledge that many research projects entail a certain degree of risk (even if that risk is minimal or if the consequences are primarily social and reputational rather than physical). If compensation for participation is significantly higher than other standard earning potentials, individuals most in need of financial resources may be more willing to overlook the potential risks of participation. In this way, disproportionately high compensation means that low-resourced communities shoulder an unfair portion of the risk involved in academic research (Gelinas et al., 2018).

Additionally, while participants—even within the same study—may enter the research with differing financial backgrounds and compensation-related needs, most institutional review boards (IRBs) do not permit researchers to pay participants different amounts within one study. By offering flexible options for both participation and payment, the EPCM can help address this contradiction by making research involvement more accessible to people with varied financial needs and abilities. The proposed model most directly applies to research involving qualitative data collection, such as interviews, focus groups, or open-ended surveys. However, we present guidelines for modifying and further developing the model to fit other research needs in the section entitled “Modification and Development” below.

EPCM Tutorial

Step 1: Prepare to Engage with Your Participant Pool

-

Research in the U.S. predominantly centers the viewpoints and experiences of White, educated, and wealthy individuals (Liu et al., 2023). Ensuring that your participant pool represents multiple groups and perspectives will improve the quality and generalizability of your research. However, participants with different needs and backgrounds may require different supports to facilitate participation. To ensure the successful participation of individuals not typically centered in research, you must be aware of the factors that may influence a participant’s perspective and participation. The factors below may only be relevant to some research projects, and some research projects may need to account for additional factors not included here. Still, as the first step of the EPCM, prepare to solicit information about the following factors from your participants during your first meeting.

a. Race

- Example question: “With which race(s) or ethnicity(ies) do you identify?”

b. Ability

- Example question: “Do you prefer to respond to interview questions verbally or in writing?”

c. Socioeconomic status

-

Example question: “What is your current professional position?”

-

Example question: “What is your highest level of education?”

d. Gender

- Example question: “What is your gender identity?”

e. Geographic location

- Example question: “Where do you currently reside?”

f. Area of expertise

-

Example question: “Is your background in research or academia?”

-

Example question: “Are you an active practitioner in your field?”

-

Example question: “What is your professional area of expertise?”

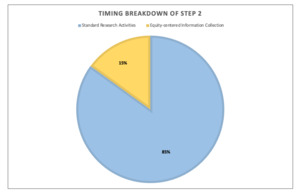

Step 2: Initiate Equal Participation & Compensation

-

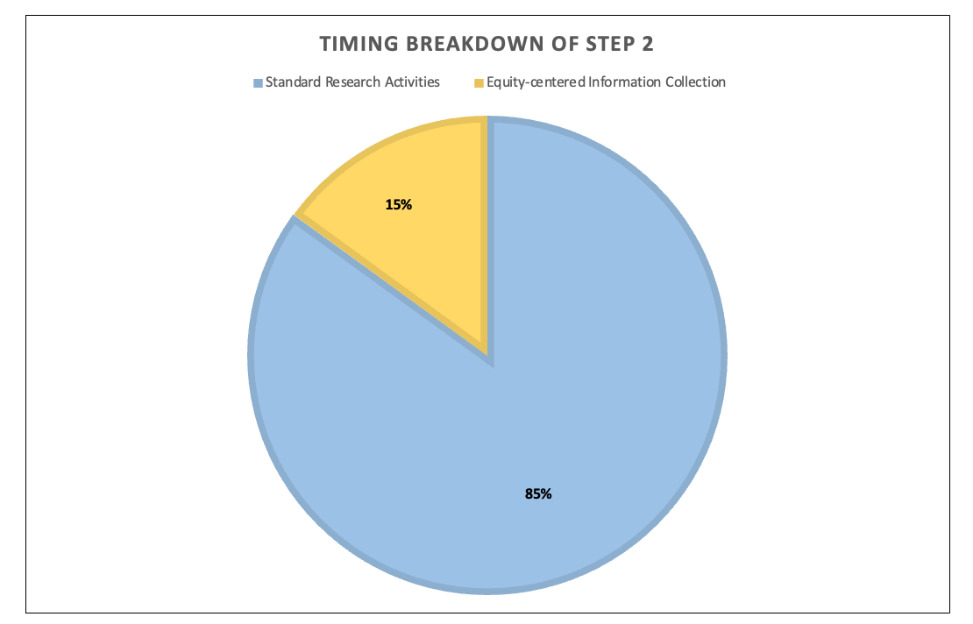

Invite all recruited participants for an initial round of participation. Depending on the study, this might involve an expert interview, a focus group, a survey, or another method entirely.

-

During the initial participation round, set aside 10–15 minutes to collect the essential equity-centered demographic information listed above.

-

At the end of the study, tell all participants that if they have additional information to share, they should feel free to reach out to the study team and expect to be further compensated depending on the depth of additional information they provide.

-

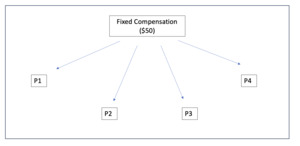

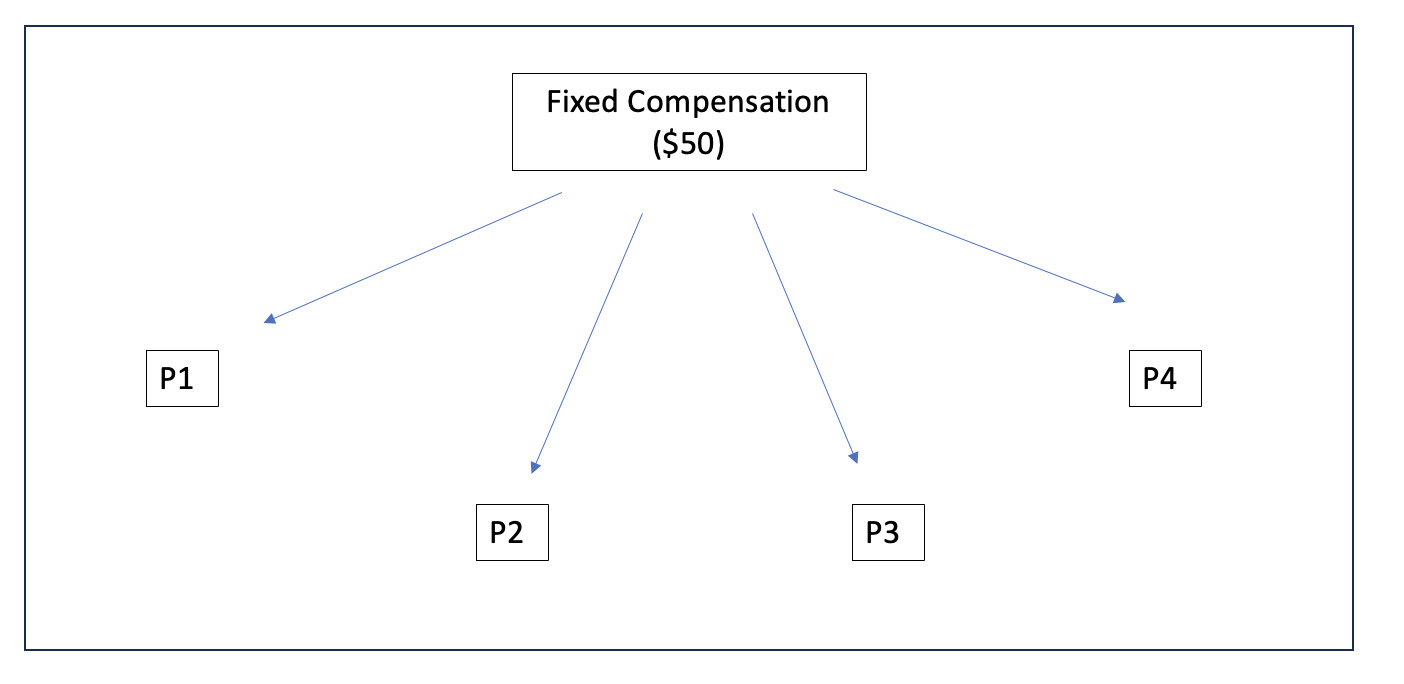

Following the study, compensate all participants equally. For one hour of participation in 2023, we recommend paying $50 for tasks such as expert interviews or focus groups.

Step 3: Selectively Solicit Equitable Participation & Compensation

-

After the initial interview, you should solicit additional participation from certain participants whose perspectives, identities, or areas of expertise still need to be better represented in your research field. In order to implement the third step of the EPCM, complete the following re-contact steps:

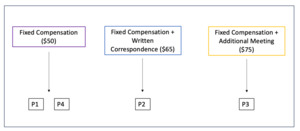

a. Refrain from reaching out to participants whose perspectives and areas of expertise are well-represented in your field of study.

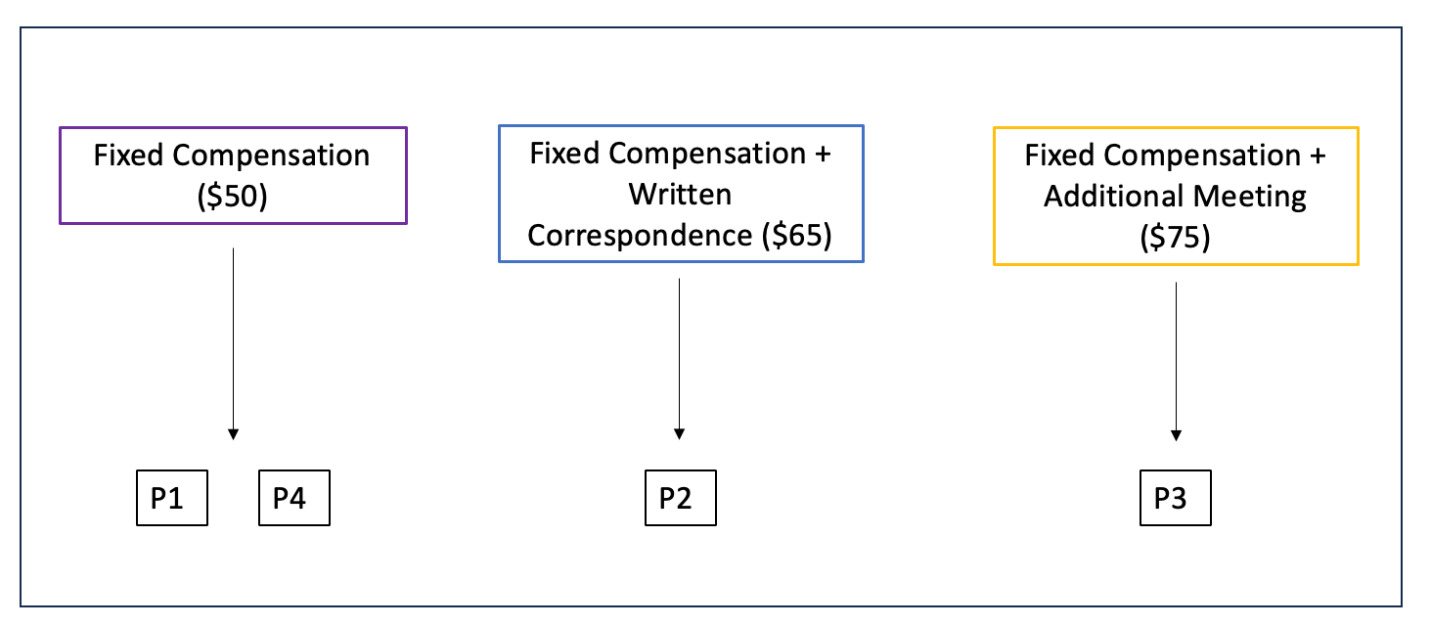

b. Consider contacting participants with some underrepresented expertise or perspective for small, additional contributions, such as an asynchronous email exchange or brief written response.

- We recommend compensating these participants an additional $15 for their work.

c. Consider reaching out to participants with several underrepresented areas of expertise or perspectives for more substantial additional contributions, such as another brief conversation.

- We recommend compensating these participants an additional $25 for a 30-minute follow-up conversation.

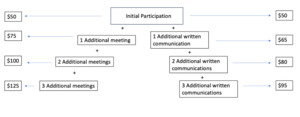

d. For budgeting and ensuring balance across the participant pool, we recommend soliciting no more than three additional interactions with any single participant.

Step 4: Allow for Bidirectional Agency

-

As an essential component of equity-centered compensation, it is vital to ensure that participants have some agency in the total amount they may earn from the research. Selectively soliciting information from underrepresented participants in Step 3 will ensure that those who might be less comfortable coming forward are still centered; however, it is crucial to redistribute some of the decisive power back to the participants rather than holding it entirely within the study team.

a. Participants who reach back out and share additional substantive information over email should be compensated an additional $15.

b. Participants who reach out with enough additional information to constitute a 30-minute synchronous conversation should be compensated an additional $25.

c. To budget and ensure balance across the participant pool, we recommend allowing for no more than three additional interactions with any single participant.

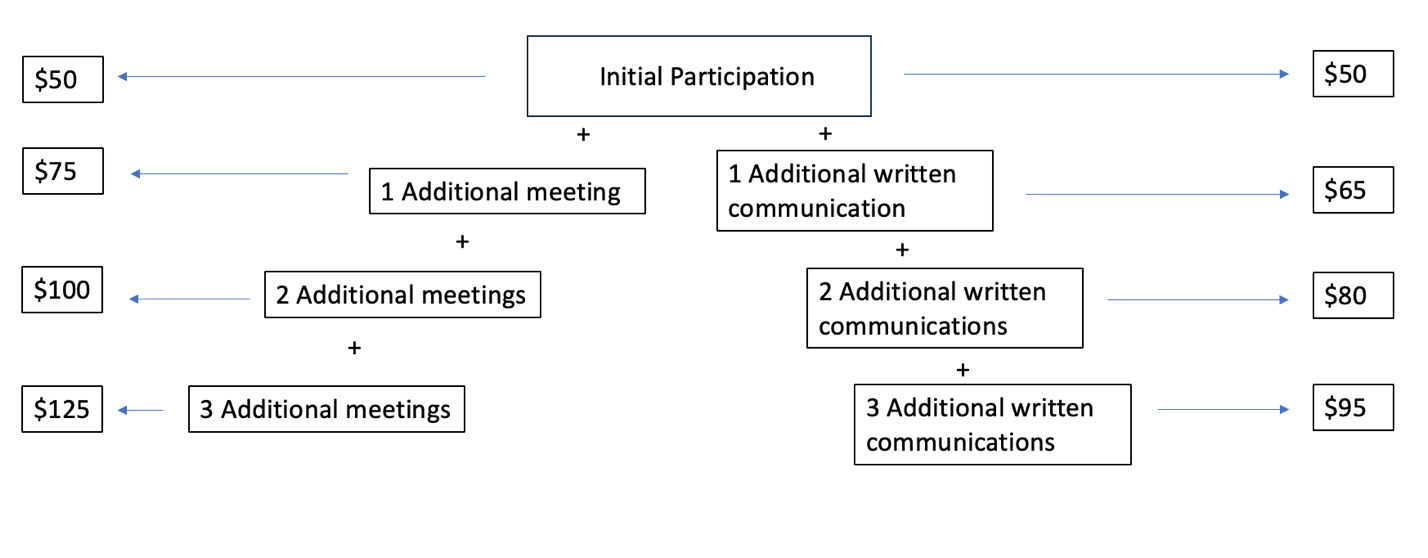

Ultimate Compensation

Because of the bidirectional agency in this methodology, final compensation amounts will fluctuate depending on participants’ and researchers’ preferences. Following the compensation amounts detailed in the EPCM tutorial, Figure 4 shows some of the available final compensation options for participants in a study, depending on the type and number of participant contributions. For research that utilizes expert interviews or similar methods, the amounts below provide a benchmark of reasonable compensation rates in 2023 for this type of participation considering time spent, market value, and equitable distribution of resources. Note that specific amounts must be adjusted for inflation and market value shifts.

Case Study

The EPCM has already been implemented in several research projects at the RAND Corporation. Specific information about how the model was applied to one such project is provided below.

Study A

The EPCM was developed with a research project to identify the relationship between art and child/youth well-being. The project involved interviews with experts relevant to child/youth well-being and art, including academics, social workers, community organizers, activists, and teachers. Every expert identified was invited to participate in a 60-minute phone interview and was informed they would be compensated $50 for their time. The $50 for an hour of labor was determined to be a competitive rate in most participants’ fields; however, it is not so high that it alone would convince unwilling participants to overlook any concerns regarding their participation.

We hoped to receive additional feedback from participants not typically well-represented in the scholarly conversation about arts and youth well-being so that our final report would more heavily center their voices and perspectives. With this in mind, we invited some participants to provide specific, written responses to questions after the initial interview. We also invited others back for additional 30-minute conversations for more in-depth discussion. These participants were invited back between one and three times each. Participants were compensated $15 for every written response, and for every 30-minute interview, participants were compensated $25.

Some participants followed up with us and asked to schedule additional conversations to continue sharing insights, even though they had yet to be asked. The study team agreed, and these participants were compensated for their time in the same way.

Modification and Development

We understand that the EPCM’s exact sequence and compensation amounts might differ for some projects. As such, the following section outlines our recommended criteria for developing and applying the EPCM to your research project. These recommendations are modeled on the RAND CAREP study team’s strategy to develop the EPCM.

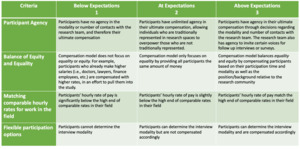

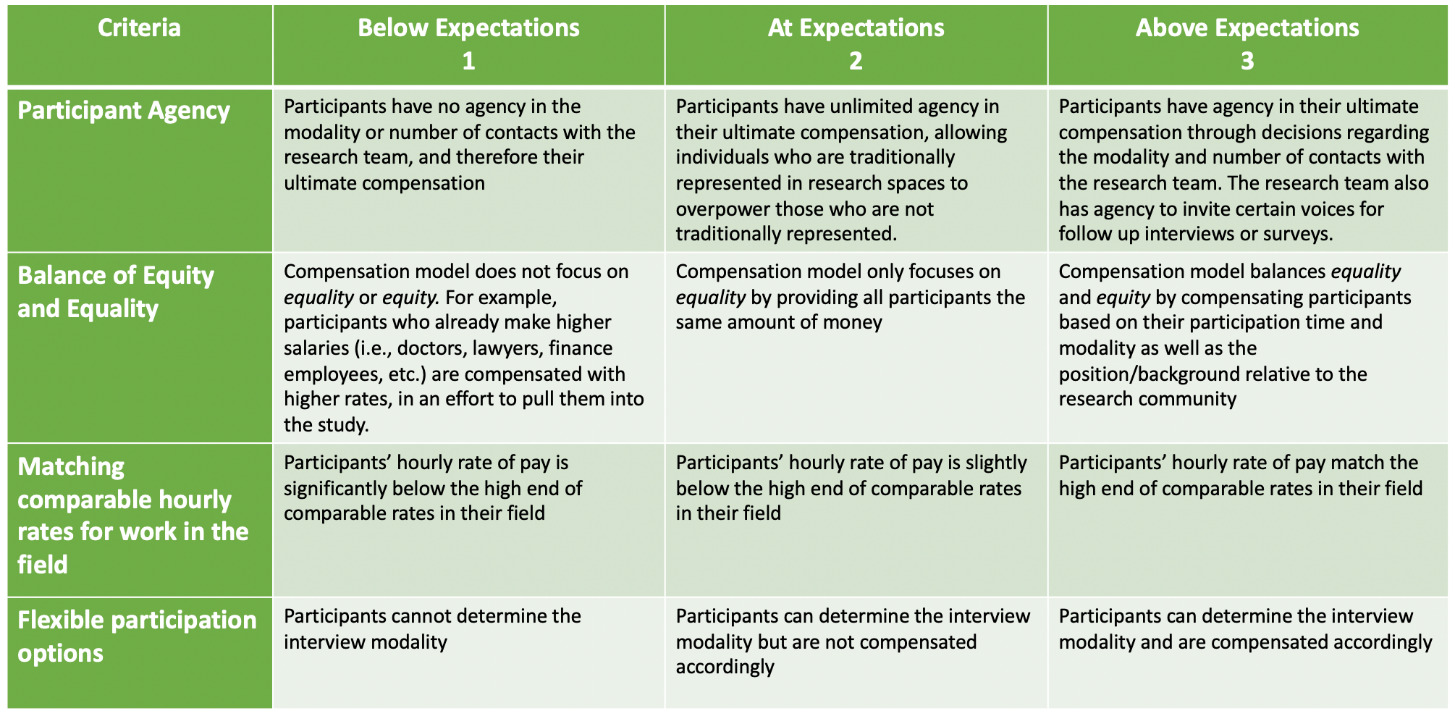

Determine appropriate compensation amounts for your research

While the EPCM was developed with tasks such as interviews, focus groups, or surveys in mind, the compensation method can be applied to other research activities as long as the amounts are adjusted accordingly. The RAND CAREP team utilized the table below to develop the specific amounts for the EPCM. We recommend utilizing the criteria outlined in this table for determining the appropriate compensatory amounts for your research activities.

Evaluate your own participation and compensation methodology

In research activities, compensation is directly related to effort and time spent on participation. As such, the structure of your research must allow for flexibility between participants in terms of the amount and type of participation, such that both the study team and participants have agency in shaping their ultimate involvement and compensation. The following rubric presents general guidelines that research teams may consider when evaluating their success in centering equity principles in their compensation practices.

Navigating Restrictions

Institutional Review Boards (IRB)

The goal of the IRB is, among other tasks, to ensure that research compensation is fair and proportional to the work required and that there is no undue influence on participants to experience risk for the sake of a study. Most IRBs are accustomed to a compensation model that centers equality, wherein every participant is paid the same amount of money and asked to do the same work simultaneously. When centering equity, however, it is essential to acknowledge that every participant has different needs and backgrounds that make participation demands distinct. Relatedly, many fields may benefit from rebalancing the influence that White, educated, able-bodied, and similar participants have on the final results, given the amplification their voices have had thus far. When implementing non-traditional compensation models that center equity principles, explaining these factors to the IRB and working closely with them to develop a comfortable plan for everyone is essential. Ultimately, the IRB has the same goals as an equity-centered research team—to protect the interests of the participants. By collaborating closely with IRB reviewers, studies may be able to implement compensation models that stretch and grow the understanding of institutional review boards about their equity practices and may impact the practices enabled in their institution as a whole.

Grant Proposals

Many grant proposals require the specification of an exact cost for participant compensation, typically outlined by the number of participants and cost per participant. To work around this restriction, estimate the number of participant interactions you hope to have in your study rather than the total number of participants. Speaking with one participant three times is equivalent in cost to speaking with three participants one time each. In Case Study A, the research team budgeted 50 participant interactions; however, we began by recruiting only 25 participants. After interviewing all participants, it was clear which participants we hoped to bring back for additional conversations, which participants themselves hoped to contribute further, and, therefore, how many slots we had left over to recruit additional voices not already well represented in the first participant pool.

Documentation

For research conducted within specific settings, there may be additional registration requirements for participants, such as completing W4 paperwork or registering as a consultant or vendor. We recommend consistently noting participants as hourly earners. Because the EPCM does not suggest paying participants differently for the same work but instead suggests that some participants be involved in the work more than others, all participants earn the same hourly wage. In this way, participants might be compensated similarly to hourly lab assistants who work varying hours but receive equal pay.

Conclusion

As this model proposes, by offering flexible payment options and amounts, researchers, organizations, and diverse stakeholders can work together in equitable relationships, and research processes and products can be made more accessible to people with different financial needs and backgrounds. The EPCM provides opportunities to give more voice to those traditionally excluded from the research interview process. We hope this model can be adaptable to diverse spaces (e.g., focus groups, interviews, sound bites, and podcasts, among others). The need for these types of equitable entry points is critical, and we hope the EPCM contributes to the overall progress of financial equity in research spaces.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Wallace Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

“The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities worldwide safer, more secure, healthier, and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest” (RAND Corporation, 2023). At the RAND Center to Advance Racial Equity Policy (CAREP), equity, diversity, and inclusion are central to our ability to produce high-quality, objective, and well-contextualized research and analysis that can impact the public good. We apply these concepts in all our research processes, from proposal development and study design to disseminating research findings.