Introduction

Practitioners and researchers have increasingly recognized the benefits of collaborating with youth, which results in better outcomes for the young people themselves, the adult partners, and a variety of programmatic and research goals (Anyon et al., 2018; Langhout & Thomas, 2010; Malorni et al., 2022; Ozer, 2017). To better understand and support teen perspectives, scholars suggest engaging with youth via participatory methods (Anyon et al., 2018; Ozer, 2017). Participatory methods in research are promoted in a variety of fields and theories, which, most notably for our work, include positive youth development, critical youth studies, library and information science, public health and design, and human-centered computing (Bertrand, 2016; Branquinho et al., 2020; Powers & Tiffany, 2006; Quijada Cerecer et al., 2013). These methods allow us to recognize and mitigate power issues inherent in work between teens and adults and help us empower youth and acknowledge their expertise and priorities (Wong et al., 2010).

In the work we present here, we combined practice and research. Teens engaged in participatory activities within their local youth service organizations (YSOs) and these participatory activities were simultaneously used as research activities. The participatory methods were all conducted virtually and designed from the beginning to operate online. Unlike research developed for in-person methodology that moved to virtual methods during the pandemic (i.e., Filoteo et al., 2021; E. S. Valadez & Gubrium, 2020), our research was designed to be online from inception. Although activities were not conducted face-to-face with the researchers, the process empowered teens, strengthened teen relationships with organization staff members, and may lead to procedure or policy change within the YSOs.

In this paper, we describe our multi-phase approach to conducting research using participatory methods with teens and the adults who work with them as a part of YSOs. We discuss three participatory design-based research activities and detail the tools we used to support our collaboration. We: 1) contribute evidence for the value of drawing on design approaches for participatory methods; 2) articulate benefits and considerations for intentionally doing so online rather than as a pivot; and 3) share techniques that emphasize voice in both research and organizational partners’ program development and management. This approach allowed teens to gain experience with research activities, including critical thinking, data analysis, and developing presentations and publications. Herein, we discuss lessons learned and share guiding questions to support others using digital tools and platforms for participatory study design. We then detail implications for research and practice, sharing guidelines and examples from our case study demonstrating ways to collaborate with teens in research beyond a tokenistic approach.

Engaging Youth in Participatory Methods

While some fields include youth-based participatory processes in the same category as community-based participatory research (CBPR), others use the term and definition of Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR). CBPR is common in public health and tends to include opportunities for community participant involvement in research, providing new information and action that leads to social change (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). In comparison, YPAR is defined as applying participatory methods to research involving youth (Anyon et al., 2018; Malorni et al., 2022). YPAR processes allow researchers to draw upon the expertise of youth, creating opportunities and projects that are equitable and inclusive and lead to impact and action change (Ozer, 2017).

While YPAR informs our work, we were not able to directly involve teens in all aspects of the research process, such as determining the research question, analyzing data, and reporting findings to adult audiences. Our work uses participatory methods informed by design methods to engage teens in various ways around the same research objective (Nind & Vinha, 2016; Spinuzzi, 2005). In our research, teens engaged in participatory design activities intended to minimize power differences between adults and youth, with the intention to enable teens to better express their voices to a variety of adult audiences.

It is important to authentically engage youth in the process, analysis, and formation of the final outcomes within the participatory practices. A challenge in youth participation work is avoiding instances of tokenism, including youth input in ways that impact decision-making or allowing time for youth to engage in the decision-making process and see the results (Lundy, 2018; Tisdall, 2013). In addition, the participatory process should address the power adults hold in the relationship and how that power impacts youth participation (Tisdall, 2017). While involving youth in processes that are not authentic in leading from participation to change, youth may perceive themselves as “accessories” (Yamaguchi et al., 2023). However, the risk of the negative impacts of tokenism should not prohibit attempting to engage young people in participation and decision-making, as some engagement may be better than none (Lundy, 2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic had widespread impacts on “social research, and most acutely, participatory research,” and our project contributes to the growing literature that considers the opportunities and challenges of distance participatory methods (Hall et al., 2021, p. 1). The need to adjust participatory research design due to the pandemic included both pros and cons. While digital approaches allow an increased pool of methods, flexibility for applying them, and opportunities to connect with audiences at a distance, increased dependency on technology can also invite increased problems associated with factors like technology skills and access (Sattler et al., 2022). There have been a variety of approaches to conducting this work at a distance, including creative approaches that include photo voice and digital diaries (Hall et al., 2021). In the early response after the pandemic began, research with youth was particularly adept at employing creativity, using a wide range of artistic techniques like animation, collage, comic strip, drawing, craft, digital photography, and film (Sattler et al., 2022), as well as design-influenced methods like those we developed.

In addition to these opportunities and challenges, distance research approaches also had expanded ethical considerations, as participation in research may come with higher risks during stressful times (Hall et al., 2021). These considerations were further magnified for research with young people. Youth are historically underrepresented in popular and government discourse and responses to the pandemic further limited that engagement while simultaneously mandating stressful changes to learning contexts and increased technology use for school (Lomax et al., 2022). Despite the “new and emerging context of the pandemic,” we and other youth researchers emphasized how “we might best respond to and not lose sight of the important and explicit shifts in practices toward doing research with rather than on children” (Lomax et al., 2022, pp. 31–32).

To support our research in collaboration with youth, in addition to the theoretical and empirical research motivations described in the noted fields, we also drew on our experiences as practitioners. The three authors of this paper each have professional backgrounds in public service contexts working with youth: one as a designer, one as a county-level 4-H youth development educator with a state Cooperative Extension Service (National 4-H Council), and one as a public teen service librarian. Drawing on participatory perspectives from each of our work domains enabled us to approach research with teens in the midwestern United States as a partnership.

Our research and practice goals sought to understand successful youth experiences in out-of-school-time and community-focused YSOs. Our work focused on youth with historically marginalized identities in the United States, specifically those who identify as BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color) or LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, and other marginalized sexual orientations, gender identities, and expressions). With this project, we wanted to understand how youth or teens, defined as 13–19 years old, describe successful experiences in YSO settings, how adults define success, and the connections and differences between these two perspectives. Our work also sought to impact youth services and programs by sharing youth perspectives with the YSOs to inform the future development of programs and services while increasing the opportunities for teens to become partners within their chosen organizations.

In YSOs, dedicated adults curate experiences to support youth agency and positive developmental outcomes, incorporating concepts of inclusion and intersectionality (Arbeit et al., 2019; Bocarro & Witt, 2018; Greene et al., 2013). These experiences range from youth-driven service-learning projects to youth mentoring programs and safe spaces to connect informally with peers (Dawes & Larson, 2011). Our project collaborated with youth and adults from five YSOs in the same mid-sized community to understand how these organizations address and support equitable and just outcomes for youth and, crucially, how the youth they serve understand and perceive these efforts. We defined mid-sized communities using the National Center for Educational Statistics (2019) definition of towns with populations between 100,000 and 250,000 individuals. Each YSO we partnered with has a history of serving diverse audiences, from youth who identify as Hispanic or African American to recent U.S. immigrants and youth who identify as LGBTQIA+. These organizations also promoted civic engagement within their programs and policies.

Previous work examining historically marginalized youth and their experiences in civic organizations often focuses on formal educational institutions, including elementary and secondary schools (Cole, 2007), community colleges (Ivery, 2013), and universities (Neville et al., 2010). The emphasis on formal settings can miss out on the impact of out-of-school time and community-focused YSOs that provide opportunities for teen audiences to learn and engage in diverse communities while practicing civic engagement. In the spirit of a just and equitable society, this project aimed to develop a framework for community collaboration between the YSOs based on the youth-centered strengths of each organization, prompting collective action to better support youth as individuals. Our process, described below, is a case study in participatory methods with teens engaging via virtual settings. We believe this work is relevant for researchers and organizations seeking to expand their participatory repertoires in both research methods and program engagement. While this case focuses on teens, the methods we describe, the considerations we highlight, and the implications we discuss are relevant to other groups and identities.

Context of the Study

Our study began in the summer of 2021 and continued through winter 2022. We focused on connecting with organizations within one mid-size community, conducting our work in the midwestern United States. Our approach allowed us to learn from various perspectives and experiences and supported our later goals of building inter-organizational connections within the community.

We purposely chose a mid-sized community for our work. In the midwest, mid-sized is caught between the less populated rural regions and the highly populated metropolitan centers of cities like Chicago, Indianapolis, and Minneapolis-St. Paul. Mid-sized communities have a large enough population that multiple organizations often work to meet the needs of the teen population. However, their services and opportunities typically pale in comparison to their larger counterparts with millions of residents. Both teens and adults in our research talked about visiting family and friends in the state’s metropolitan center. The teens also complained that their mid-sized community offered “nothing to do.” Compared to rural areas with few services, their mid-sized communities provided a great deal but when compared to a city with over a million residents, their mid-sized community seemed small.

This work was firmly situated during the coronavirus pandemic, and local health guidance around safe face-to-face interactions was adjusted regularly. The various guidelines had a direct impact on the research safety requirements of our university, as well as the availability of the organizations and participants. Our university safety requirements did not allow for travel, meaning our only method of engaging with participants was online, often called “virtual.” In addition to the virtual nature of our data collection, we were also able to explore the use of online engagement in the lives of the youth and the YSO staff members as they navigated the local pandemic health guidelines.

Given the variable public health constraints, all YSOs were remarkably flexible in engaging in our research. One impact of the pandemic was that many participants had experienced limitations on their face-to-face social interactions and had managed virtual school and community interactions for some time in advance of our study.

We also note that beyond the pandemic’s impacts on public health, learning, and social life for our participants, significant racial injustice—with some nationally covered cases occurring in close proximity to participants—was also a factor in the daily lives of these youth and youth services providers throughout the course of our study (Horsford et al., 2021). The YSO adults mentioned that during the heart of the pandemic, when in-person programming stopped, they received text messages from their youth about “George Floyd” and “police violence” and offered virtual Zoom meetings to connect and provide space for youth to share their thoughts and experiences. When in-person programming resumed, these Zoom spaces persisted for those still not comfortable meeting in person. As researchers, we were also sensitive to this context which informed our study’s emphasis on understanding participants’ self-described racial and ethnic identities.

Reflexivity

The national context of racial injustice also influenced our positionality as researchers. The two first authors identify as white and we intentionally structured study interactions to minimize power differentials between ourselves and our diverse participants. Indeed, this is a consistent motivation for our selection of participatory methods. All three researchers bring various backgrounds and identities that shaped how we entered and interacted with the teens and adults in our study (Reyes, 2020). Both Magee and Leman have a background working with youth service organizations. Leman used contacts from her previous work to start the process of connecting to the YSOs in the study. Balasubramaniam, the third researcher in the study, is an international graduate student with experience working with youth in school participatory design contexts and drew from the experiences of engaging young people in collaborative and creative processes through a culturally diverse lens. In our study interactions, all researchers drew on their previous experiences facilitating youth programs and services. The researchers also reflected that they reverted to mannerisms and ways of communicating with teens similar to their styles when working with teen audiences in practice settings.

Participants

We collaborated with five community-based YSOs and worked with 13 adults and 32 teens across the organizations. Through an anonymous online survey, adults and youth answered open-ended questions about their backgrounds (e.g., How do you describe your racial identity? What gender do you most identify with? What sexuality do you most identify with?). The open-ended questions allowed participants to express their views in the words or language they felt most appropriate. See Figure 1 for more information about the demographic characteristics shared by our participants. Over a third of the teen participants shared non-dominant gender and sexual identities, and almost three-quarters identified as part of a historically marginalized race or ethnicity. Among the adult participants, 38% identified as a historically marginalized race or ethnic identity, and 15% shared non-dominant sexual orientations.

The five community-based RSOs were chosen from recommendations by local community members involved in human service organizations and a study invitation was also shared in a presentation to the local youth programming coalition. The organizations represent local chapters of national youth-serving organizations, a local nonprofit, a school-based program, and a library-based program. Teen programs varied from meeting once weekly to meeting every day after school. Program participant numbers are hard to categorize as pandemic numbers did not match pre-pandemic numbers. During our study, the number of participants fluctuated for each organization. In order to protect the identities of the organizations and their staff members, we are not providing additional information.

Research Design

In order to address our research question, How do teens and adult leaders describe the qualities and practices of support provided in youth service organizations (YSOs)?, we discuss two research phases, with more details in Figure 2. In the first phase, designed to prime the conversation, we completed virtual interviews with YSO staff members and virtual focus groups with teens from each organization and asked about their experiences and relationships while at the YSO programs and events. In the second phase, designed to generate new ideas and connections, we met with a virtual focus group with individual YSOs, including teens and adults who were part of the first phase. Our institutional ethics review board reviewed and approved these activities and processes.

The three design-informed participatory methods for our study are termed activities in Figure 2 and were designed by the researchers based on best practices in the literature for both participatory methods and design activities. We included two participatory methods for data collection and one for collaborative analysis. We discuss these below in the order they were used in the study: Design Activity 1: Priming Activity; Collaborative Analysis Activity: Do You Agree?, and Design Activity 2: One Billion Dollar Challenge. Participants were not involved in methods design; however, the activities were designed to increase the level of participation and engagement of the research participants compared to only verbal interviews and focus groups and to include a level of co-analysis in the project’s second stage.

We continually reviewed local public health and research regulations which mandated distanced interaction during our work. These updated regulations informed all of our work and methods. Throughout the following description of our research activities, we share details and considerations regarding the technological platforms we selected. Our overarching motivations for these selections included ease of use, accessibility, and minimizing costs for participants and organizations.

Research Design: Design Activity 1 - Priming Activity

Our first participatory activity involved working with teens to prompt reflection before the more traditional research study activities, a common practice in participatory methods (Spinuzzi, 2005). We shared a prompt that we call a priming activity, which incorporated perspectives from design methods, such as metaphors, textual and visual expression (Casakin, 2007; Nind & Vinha, 2016), and theoretical constructs from positive youth development (Bowers et al., 2015; R. W. Larson & Walker, 2018). We shared the priming activity in a worksheet emailed to the organization leaders to print and distribute to teen participants or email directly to the teens (Balasubramaniam et al., 2022). We set up a study-specific email through one of our campus unit’s technology support teams. The email address allowed us to use campus-approved platforms, better protect participant privacy, and included campus affiliation in our contact information (e.g., “youthstudy@university.edu”). The university email address can lend authority to online communications but also may present issues when community members have contentious relationships or histories with the institution. Teen participants could email us their completed versions by scanning or photographing their work before the focus group. The teens were asked to bring their priming activity to the first focus group as a prompt for discussion and to share with other participants and the researchers in the online meeting room.

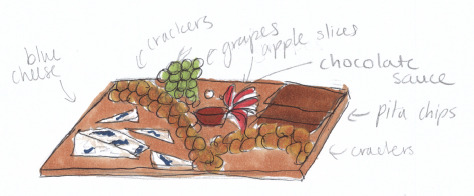

The first prompt of the priming activity asked teens to reflect on their positive relationships with adults (besides the adults they live with at home) and brainstorm everything that came to mind. An empty box was available for participants’ writing or drawing. Next, teens were asked to “describe your relationship [with one of your favorite adults you enjoy spending time with who does not live with you] as a meal, like a picnic lunch or bento box.” The worksheet included a definition of a bento box and a sample drawing. In Figure 3, we share an example illustration, which the teen participant described in the following way:

“I included blue cheese because it’s a firm cheese but also quirky. Crackers and pita chips because they are earthy and grounded, I think I appreciate this adult because they are very dependable and steady, which is represented in that I included fruits to represent familiarity and support.” - PARTICIPANT ID T2-FG1

In this priming activity, we used the idea of metaphors to encourage participants to draw and describe a positive relationship as a lunchtime meal. Metaphorical reasoning allows people to understand a situation through an iterative process where the insights are emergent (Casakin, 2007; Nind & Vinha, 2016; Sanders & Stappers, 2018). Juxtaposing concepts that share certain features but differ in others helps structure thinking and represent situations with a new perspective. The heuristics of analogies or metaphors help participants organize their thinking and restructure ill-defined or ambiguous problem statements.

While qualitative inquiry techniques such as interviews and focus groups surface explicit and observable knowledge, design methods like this can emerge tacit and latent levels of knowledge and enable people to express them. The role of design methods is about more than the deliverables they generate. Rather, it’s how they help structure conversations to elicit the information needed to inform the research. Participant collaboration is traditionally put forward as data, analysis, or findings (Branquinho et al., 2019; Shamrova & Cummings, 2017). However, design methods like representing a relationship through a meal allow the process to encourage participants to share experiences, develop a shared language, break down conceptual and experiential boundaries, and invite equitable collaboration in participatory research.

Research Design: Collaborative Analysis Activity - Do You Agree?

In the second phase of our work, we conducted focus groups with each organization, bringing together the teens and adults who had previously participated in interviews and focus groups for an additional, larger group conversation. In this activity and the final design activity, focus groups allowed for synchronous communication, socially embedded interactions, and the iterative development of ideas. We began our focus group discussions using a version of member checking (Birt et al., 2016), sharing preliminary themes and evocative quotes from those earlier interviews and focus groups via an online whiteboard. Each of the second phase focus groups centered around the individual organization; e.g., the quotes and examples for the phase 2 discussion about the library organization included only quotes from the round one library organization interviews and focus groups. In building on a shared understanding of what success looked like for the teens, adults, and their organizations, we expressly incorporated responses from the teens and the adults around themes we had identified in their individual organization discussions.

To integrate the YSOs’ responses, we provided examples and quotes that evidenced patterns and themes in a preliminary analysis of their responses. We focused on elevating the teens’ perspectives, sharing multiple statements from teens, and typically supplementing with one quote from an adult for each theme. For each session, we asked participants to read each theme and the associated quotes and respond with their own thoughts using one of the many tools on the Jamboard platform (sticky notes, text, pictures, or drawing tools). Online whiteboard spaces like this have been used for synchronous collaborative design (Metz et al., 2015) and with students to discuss learning tasks’ results and bolster collaboration skills (Rojanarata, 2020). Further, these “innovative co-creation methods can elicit diverse experiences and impact change in services, systems, and policies” (Micsinszki et al., 2021, p. 2). We selected Google’s Jamboard because it had a relatively low barrier of entry—no accounts were required, and many young people were used to using Google Suite and Google Classroom services. We found that all our participants (teens and adults) were quickly comfortable with participating this way but anticipate that other audiences might have less familiarity with these technologies. We also note that in late 2023, Google announced that the Jamboard service would be retired, pointing to plans for integration with other online collaboration tools. This highlights an important consideration for online research: tools, access to them, and their levels of support are constantly changing.

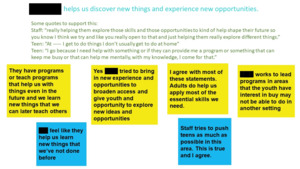

In our sessions, the response process included approximately ten minutes of individual reflection and response. We then held an open discussion about each theme, where participants could share their perspectives via voice/video/chat. Adult participants, likely influenced by their general orientation to youth services, let the teens lead the way and typically responded after the youth had an opportunity for discussion. Figure 4 shares an example of an organization’s theme, supporting quotations, and responses from focus group participants. References to the organization are redacted.

Adults often focused on how valuable it was to hear youth perspectives in quotes and examples supporting the themes and discussions about them. One adult participant even asked for a collection of the quotes to share with other adults at their organization. At another, the results from this portion of the work were included in an organization-wide strategic plan.

We note that using focus groups generally comes with an increased risk of privacy violations. Before each focus group, we read our ethics board-approved statement to the participants, which acknowledged that we could not control what other focus group members said outside of the session but requested that all respect confidentiality as the focus group method does not allow for anonymity with the participants (Sim & Waterfield, 2019). Additionally, as we were using video technology, we were unaware if other people were in the room but not visible on cameras. In instances when adults were supervising the focus groups in the same room, the adults were privy to the conversations. Even though we took measures to mitigate these risks and our work occurred in pandemic conditions, as future work with teens in virtual spaces persists, it is essential to further explore the ethical issues around consent, confidentiality, and anonymity.

We layered the Google Jamboard online whiteboard onto synchronous Zoom meetings. Zoom was heavily adopted early in the pandemic in the United States, including for public education institutions that many of the teens in our study attended (Joia & Lorenzo, 2021). There are inclusion issues with using this, and any, platform, such as the requirement that participants have access to a computer or phone and internet access for meeting participation. Zoom fatigue, the exhaustion that arises in online meetings, is also a consideration for these data collection methods, particularly with youth mandated to participate in school through the platform during the pandemic (Nesher Shoshan & Wehrt, 2022).

While conscious of these issues, when our study took place, we had just come through one of the most restrictive shutdowns in our state, and most participants had opportunities to experience online meetings with this platform. We designed our interactions to support flexibility in participation, allowing for audio, video, and chat-based participation. Most focus groups included participants congregating at the physical locations where the organizations met, with teens attending the focus groups in the same room (though they wore masks during these interactions because of the shared space). This shared space allowed us to replicate some of the experiences of a traditional focus group, including allowing for social interaction and conversational flow and increased comfort levels with the space for participants. At times, the fact that teens shared the same computer, the varying amplification of their voices, and the physical barrier of masks all presented difficulties associated with virtual focus groups, including difficulty hearing and transcribing individual comments.

Research Design: Design Activity 2 - One Billion Dollar Challenge

During the first phase of our project, one of the overarching themes across all organizations was the connection between relationships, experiences, and physical space in the organization buildings. We concluded the phase 2 focus groups (conducted using the same technology platforms as the collaborative activity) with an additional design activity focused on learning more about this concept. We asked participants to imagine how they would redesign their organization’s space with a donation of one billion dollars, an activity we refer to as the One Billion Dollar Challenge. The dollar figure is deliberately chosen to take the obstacle of funding out of their brainstorming, realizing money often becomes an artificial barrier to change.

Each focus group participant had their own Jamboard slide and could use drawings, text, sticky notes, and images to design the space. Participants communicated their priorities for the new space as well as concepts from the current space that they would want to keep in the future. Participants used the platform’s affordances in various ways, including creating text-based responses with varying levels of complexity (Figure 5) and colorful, expressive collages of images (Figure 6). These examples demonstrate some benefits of using an online whiteboard to support data collection. Participants could use their own skill sets to choose their methods of participation. They could create and iterate on their responses to allow for more intentional expressions that better represent their ideas and their relationships (such as arranging sticky notes or images by theme).

As with the collaborative analysis activity, participants completed their slides individually, then had the opportunity to share with the group. Finally, the focus group discussed the most critical aspects of the slides. During this activity, we again emphasized the perspectives of teens. The number of teens participating significantly outweighed adults (at least 4:1), and the adult participants again allowed teens to lead the discussion and sharing. Taking their dream vision of the program, each organizational group developed a goal they could implement without funding based on their drawings and conversations about what they found important.

Ultimately, using a variety of modalities for interaction, including the prepared priming activity with written and illustrated elements, as well as audio, video, and chat in an online collaboration space, maximized the potential for participation and engagement. These tools supported us in building an active collaboration environment during our interactions with participants. We recommend using these activities (individual reflection, then group sharing and group discussion with guided prompts) with in-person focus group settings as well as online because they allow for agency and diverse expression in research interactions and maximize the potential for hearing from participants in the ways they are comfortable engaging.

Lessons Learned: Implications for Research & Practice

This study provides evidence for the effectiveness of online participatory techniques and serves as a model for others who may wish to leverage participatory methods online. Below we discuss some of the lessons from this case study and share prompting questions to consider when developing participatory research that engages participants via digital tools and techniques.

Match Tools to Your Audience

We benefited from working with teens and adults who serve teens, both audiences with relative comfort using technological tools and the norms of collaborating on digital platforms. If your community is less comfortable with technology, consider creating an activity to get everyone used to the digital functions needed for your research, such as a guided first interaction that instructs participants on using the sticky note or text box function. More generally, standard technological tools cannot guarantee access and, in many cases, may have accessibility limitations that are important to evaluate when planning a research study. Cost for access, bandwidth/local internet connections, and complexity of learning a new platform are all points to consider. We conceptualized the platforms we selected as “low-barrier technologies” that had no financial cost for participants, were relatively easy to use, and that the users had some prior experience utilizing—a key accessibility consideration.

Access to technology and the knowledge to use it appropriately are core elements in an equitable approach to conducting research activities with digital technologies. We know that access alone does not mean individuals can use, navigate, or participate in digital technologies (J. R. Valadez & Durán, 2007). We also knew going into the project that U.S. teens have high levels of access to mobile devices (Anderson & Jiang, 2018; Vogels et al., 2022) and that by the start of the project, participants had already spent approximately one year during the COVID-19 pandemic participating in school and out-of-school activities at their YSO through the online platforms used in our study (Zoom, Google Jamboard). While the participants may have been comfortable with the technology, their access may have been more consistent at the YSO site than at home. The teens would have access to and experience using the various virtual platforms in school settings and perhaps not in their home environment. Therefore, the YSO experience also may have increased their access to the technologies in a space outside of school.

Ensuring experienced access to tools and platforms used to participate was a core part of our approach, and we were fortunate to draw on the knowledge and experience of front-line youth services workers we collaborated with to have a clear understanding of the technological needs and experience of the youth in our study. Given teens’ heavy technology engagement, youth services providers emphasize technology literacy and use technology to support their work with youth (Hamada & Stavridi, 2014). The experience of youth services providers was also helpful when we did run into expected technical hiccups.

By taking these considerations into account and selecting technological platforms that were widely used and that our participants had plenty of experience with, we were able to minimize access and use issues that could have impacted participation. We recommend that others employing digital approaches include these considerations in their study design. Seeking details about access and experience before committing to study or activity design and assessing the comfort levels of collaborators and community members can help ensure more equitable and inclusive participatory approaches.

Structuring multiple techniques and approaches for engagement whenever possible can also enable more inclusive participation. In our Design Activity 1, participants shared their artwork or written responses on paper, by photo, or by scanning. We can see in the various reactions that participants expressed choice and agency in sharing their experiences and ideas. Similarly, in Design Activity 2, they shared their experiences and ideas through either digital images, digital sticky notes, or both. We aimed to provide and model as many opportunities for choice as possible with the intention that these options would increase participants’ comfort levels and opportunities for self-expression, thereby creating a more inclusive research environment.

Physical Space is Still Prime

Even in an online research study, participants seemed to seek ways to be in the same physical space. When given the option to join the Zoom meetings from home or a shared location, many chose to meet at a shared site. For some organizations, the teens were already at the YSO for programming, and it was easier for the participants to join together than to separate on different devices in different rooms. While the use of shared technology could have been related to limited devices, we believe the teens preferred to interact face-to-face. At one YSO, the adults tried putting the focus group all on different devices around the facility to increase the sound quality of the meeting. However, the teens still found ways to have side conversations, even if it involved “yelling” between rooms.

When research participants chose to be in the same room and respond on the same device, it was more challenging to determine which participants made each comment and to differentiate between participants answering questions as part of the main conversation or making sidebar comments. To mitigate this challenge, researchers and youth services providers could coordinate to record audio in the space where participants are gathered while using one video stream to view all participants.

While the preference to share physical space was in part related to the structure of our research (working with community organizations where teens were already engaging outside of school), we believe that preferences related to space could be leveraged in future work that is less influenced by the pandemic. Providing options to be co-located or in connection with others while using digital tools can lead to more rapport amongst participants. In contrast, a purely online context has a trade-off between seeing everyone in the same space and difficulty with sound recording and clearly hearing all comments. For researchers virtually attending, a shared space for participants made it difficult to differentiate speakers.

Thinking Beyond Physical Boundaries

While physical space is still a crucial consideration for participants, digital tools allow researchers to think beyond geographical and physical boundaries for study design. The high context available from viewing participants and allowing in-person interactions using creative research activities is superior to a conference call, even when participants choose not to turn on their videos. When scoping research and selecting communities for collaboration, conducting research online allowed us to work with communities at a distance. In the project’s next phase, we are expanding to work in carefully selected communities across the nation, enabling us to use research questions to guide decisions in exciting ways (such as seeking out other mid-size communities with a critical mass of organizations serving historically marginalized youth). This would be much more difficult to accomplish if we were planning for only in-person interactions.

Working with Organizations: Front-Line Workers and Decision-Makers

Based on our experiences as youth services providers, we designed this study to connect with youth services providers who were in direct contact with teens, whom we call “front-line workers.” We were also interested in meeting with organizational leaders (sometimes referred to as decision-makers) when possible. This occurred in multiple organizations, but we have found that this connection with front-line workers was crucial for our study. Connecting with a dedicated staff member(s) allowed the staff members to represent the study to the young people in their organization, ensuring that research interaction at a distance went smoothly and that the necessary administration occurred. The adults in our study were critical partners in ensuring our youth participants could assent/consent and that we received parent/guardian permission. The adults were veritable information technology (IT) staff for setting up computers and phones (like many who work directly with youth!). Most importantly, having those with existing relationships with the primary audience involved meant that we could build rapport more quickly and ensure that distanced interactions between researchers and participants went smoothly.

When thinking about decision-makers, we also argue that there are opportunities to show how valuable and impactful their front-line workers are, integrating these workers’ perspectives into data that informs the organization’s path forward along with the perspectives of youth. We repeatedly learned how valuable the trust of decision makers was to front-line staff. The autonomy that leaders gave these staff to make appropriate, in-the-moment decisions created a more positive perception of self and from the teens, leading to more positive participant experiences. This directly impacts the youth members of YSOs and is core to understanding success within the organizations. Similar relationships between front-line workers and decision-makers may exist in other community contexts where participatory methods are used.

What is the Role of Facilitation in Participatory Research?

Facilitation is core to the success of participatory research methods, and there is a wide range of facilitation methods for “fostering community involvement” (Coburn & Penuel, 2016; Drahota et al., 2016; Jull et al., 2017; Wallerstein et al., 2020). This study would not have been feasible without the ability to use a facilitation method grounded in youth and adult partnerships allowing teens to drive the conversations. All three of the research team members relied on their previous experiences developing and facilitating programs for teens to successfully carry out these research interactions. Given the practice-oriented stance of the fields informing our study design, we were also able to draw on scholarly frameworks that emphasize core competencies like youth engagement and leadership and cultural competency and responsiveness (American Library Association, 2010; Gredler et al., 2013; Hamada & Stavridi, 2014; National Afterschool Association, 2021). We also drew on the front-line youth services workers’ facilitation skills and the long-term relationships they had with the teens in their organizations.

Others seeking to design research that connects with communities may have similar professional perspectives to inform their approach to use as a starting point in building connections. However, always connect with the community first to clarify that your assumptions, approaches, and methods are in tune with the community. Every community is unique; what works for one only sometimes works for another. Unfortunately, it is often by trial and error that the differences are discovered. We argue that researchers with practice backgrounds bring a unique and important approach to participatory research. Even though we have practice backgrounds, we often include practitioners as partners when developing new research designs, and troubleshooting prior to implementation, all while being willing to adapt to challenges. Especially when working with youth, what seems to make sense in theory often backfires during execution.

Conclusion

While the COVID-19 pandemic significantly influenced the adoption and use of digital collaboration techniques and technologies, these connection methods are not going away. Furthermore, incorporating digital collaboration into research practices can open opportunities. While our participants may have been on the savvier end of the technology experience, we also anticipate that technological skills for digital collaboration will become more mainstream. Indeed, recently we have seen work like Madden et al.'s (2022) efforts to adapt a community-based participatory research model for work with adults in New York City in response to the need for “going virtual” in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Like the experience sampling method, used to connect with teens and youth early in its development (R. Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014), online design and participatory methods may broaden our ability to connect with a wider variety of communities.

In this paper, we shared participatory techniques we developed for conducting research online, depicting their use and impact through a case study with five YSOs in a mid-size midwestern community. Our research focused on: 1) understanding how teens and adults in YSOs understand success; and 2) how to generate participatory research insights that impact organizational programs and services. The study allowed us to develop a multi-phase model for engagement that simultaneously expanded the impact of participant voice in research and practice contexts using two design activity methods and one collaborative analysis method. Here we shared examples, evidence, details, techniques, and considerations for conducting participatory work online, highlighting relevant tools as well as the impacts and implications of these methods for future participatory work. The participatory methods maximized participant voices’ impact by informing our research while concurrently informing the organizations we partnered with. Moving forward, we call on our fellow researchers to join in expanding research impact by collaborating with communities and organizations through digital techniques and continuing to build research methods for engagement, participation, and change.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants in this study, their organizations, and those who work to improve the lives of youth. We also thank our funder, the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Campus Research Board (Award: RB21033).