Introduction

This piece is a collective reflection of three perspectives while designing and guiding a participatory action research (PAR) project as part of a larger grant. We draw on firsthand experiences of three women—a participant in the program; the PAR program director, and the grant project director—to highlight stories of the impact of PAR in the collaborative named New Orleans Louisiana Creating Access and Resources for Equity and Success (NOLA C.A.R.E.S.). This collaborative of organizations (funded by J.P. Morgan Chase) seeks to develop policies that build wealth for women who work in the early care and education industry in Bulbancha (Choctow for “Land of Many Tongues” colonized as New Orleans). One major aim of PAR in NOLA C.A.R.E.S. is to pinpoint methods of equitable access to programs and resources that build and sustain wealth in Black and Latine communities. Each participant identifies as Black and/or Latine with Participatory Action Research (PAR) as a primary feature. Although we are using the separate terms “Black” and “Latine” women when referring to our population of interest, we note that the various intersections of ethnicity and race within the African Diaspora allow for multiple and combined identities (for example, Black, African-Latina/Afro-Latina, Latinx, Afro-Latine, Caribbean Latine, and many more).

First, we introduce the landscape of NOLA CARES, a granted-funded, diverse, eleven-organization collaborative. Then, we zoom into the PAR component by defining PAR, the process, and key principles with concrete examples of centering, sharing, and ceding power with Black and Latine women as PAResearchers. Next, we highlight stories from three Black women who touched the PAR program: one who experienced, one who designed and one who supported the grant collaborative work. Finally, we conclude with learnings moving forward.

Landscape of early care in New Orleans

Louisiana has some of the highest wage inequities for Black and Latine women in the U.S. There are limited pathways to earn a good living and advance professionally, specifically for Black and Latine women in the caregiving profession. This creates a dearth of resources that contribute to disparities in caretaking and health disparities and impede wealth building. Alarmingly, early care and education (ECE) is an industry that allows all other industries to function. As of Fall 2021, only 78% of low-income New Orleans mothers with young children could afford ECE (Agenda for Children, 2022). Without reliable childcare, they cannot access economic opportunities to advance professionally, support healthy families, and build generational wealth. This is compounded by a lack of investment in ECE, a New Orleans industry that is almost exclusively owned and staffed by Black and Latine women who struggle to make ends meet. A 2021 study of Louisiana ECE workers found more than 50% are unable to pay for medical expenses, 40% are food insecure, and 30% have difficulty paying rent (LA Senate Resolution 29, 2021). Consequently, more than 20% of ECE workers report clinical levels of depression (Bassok et al., 2019). These persistent economic disparities result in enormous health disparities based on race. In New Orleans, Black children are three times more likely to be uninsured and Black adults are two times more likely to be uninsured, contributing to a 25.5-year difference in life expectancies between the richest and poorest communities in New Orleans (New Orleans Health Department, 2013).

The work of NOLA C.A.R.E.S.

A generous grant from J.P. Morgan Chase created NOLA C.A.R.E.S.: New Orleans Louisiana Creating Access and Resources for Equity and Success (NOLA C.A.R.E.S.). This collaborative of 11 organizations from public, private, and nonprofit sectors focused on wealth-building for Black and Latine women in the ECE profession in New Orleans. Organizations in NOLA C.A.R.E.S. provide policy and advocacy work, workforce professional development, and support for childcare providers. This includes peer-to-peer coaching, participatory action research, and developing capacity for childcare as a workforce benefit in the hospitality industry. Since December 2021, NOLA C.A.R.E.S. collaborative members have been engaging the public, private, and nonprofit sectors to foster practices in workplaces and public policy that value Black and Latine women. Specifically, in valuing mothers and caregivers while supporting them to build wealth through caregiving careers and businesses.

This consists of two primary and connected interventions: 1) Provide training and capital to Black and Latine childcare businesses that are women-led and women-staffed. This strengthens a model of childcare where entrepreneurs can access capital to grow; and 2) Make childcare a workplace benefit for businesses that value Black and Latine women. This should begin with the largest industry in New Orleans—the hospitality industry—which depends heavily on the labor of Black and Latine women. This initiative works to make caregiving a family-sustaining career, uplifting childcare entrepreneurship as a viable path to building wealth and creating workplaces and public policy that recognize childcare as a fundamental benefit required to advance equity for Black and Latine women.

In this grant, the lead organization is Beloved Community, a local, Black women-owned, multi-disciplinary racial and economic equity firm. The collaborative seeks to move our community of organizations away from doing for the community of Black and Latine caregivers toward a model of working with the community by supporting knowledge sharing and resource building for sustainable, community-based change. To support this process, collaborative meetings and activities focus on equitable power-building across organizational leaders. Decisions in the collaborative follow guidance from Black and Latine women leaders. Another feature of the collaborative process is language justice, where the contributions of Spanish-speaking caregivers are intentionally integrated throughout meetings. Language justice recognizes the social and political dimensions of language and language access. This process seeks to dismantle systemic language barriers, equalize power dynamics, and build communities grounded in social and racial justice.

Who are PAResearchers?

PAResearchers are folks passionate about a topic and interested in developing a research project. Participants in this project were between ages 18-70 and identified as women living and/or working in Orleans Parish who came from positions such as early care educators, grandparents, parents, hospice workers, former accountants, center directors, and literacy specialists. We call them PAResearchers because they are researchers with a particular approach to documenting expertise. They are community members who learned research tools like refining a research question, narrowing interview questions, and journaling learnings. All the while, participants sustained their hold in their community. They ranged in ages from 18 to 70. There were many differences in their experiences with children. For example, how many children they raised, how long they had been in the childcare field, and where in the city they worked. All the women wanted to learn more about PAR and pursue a research project about wealth-building over three months.

NOLA C.A.R.E.S. and Participatory Action Research (PAR)

The NOLA C.A.R.E.S. collaborative includes 12 organizations. Participatory action researchers[ers] are integrated alongside another organizational partner within the NOLA C.A.R.E.S. collaborative and their work is woven into the activities of the grant. Participatory action research is the process of collaboratively seeking answers to questions informed and driven by the community in ways that are edifying, inclusive, and regenerative (Beloved Community, 2021). By participatory, we mean community members are experts in their experiences. Following their guidance, we can change systems to better meet the needs of many communities. We focus on strategies that are inclusive and people-centered. Through action, we devise steps for change in our communities while remaining accountable to communities at all stages of research. This asks us to move with intention as we develop research designs, as research has the potential for emancipation in when community needs are prioritized through dissemination. Consequently, we focus on sharing findings and recommendations in ways that best meet the needs of communities. This process, guided by Beloved Community, engages community members in each stage of the research design: research questions, methods of data collection, analysis, and dissemination. A major aim of PAR is to pinpoint methods of equitable access to programs and resources that build and sustain wealth in Black and Latine communities. We developed and adapted research design to the needs of PAResearchers who dreamt about wealth-building in early care and education careers. Iterative and reflexive strategies were employed with PAResearchers over the course of our sessions with several cohorts of PAResearchers. For example, when developing research questions, PAResearchers reflected individually and conferred with co-workers, each other, and family members to refine the vocabulary and approach. PAResearchers and collaborative members co-created research timelines based on the daily life of PAResearchers. PAResearchers used regular member-checking from the beginning of the research design to adapt to community needs, which also built trust for decision-making.

Journey of PAR

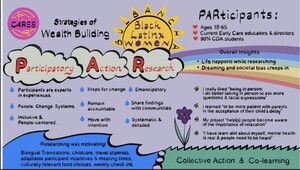

These specific strategies centered the communal practices often present in Black and Brown communities while designing research questions, methods of data collection, theories of analysis, and processes of dissemination. There were three major steps in the PAR process: training, data collection, and collective analysis/dissemination. The program involved four sessions of training in one month, one full month of data collection, and two sessions to analyze our data, individually, in small groups, and as a large group. Figure 1 is an illustration of our program.

During the training, PAResearchers spent four sessions learning about how to refine research questions, where to search for answers, different methods of asking questions, whose voices to include, and where to track findings. During the PAR training, the project director shared details of specific methods and we brainstormed which methods aligned with their research questions. We practiced interviewing and active listening. We networked to discuss community members that we could include, and how long it might take to have conversations with specific types of personalities.

Data Collection

After the training sessions, PAResearchers entered the data collection phase, where they pursued a month-long research project with twice-weekly check-in calls to debrief. During data collection, the PAR project director spoke with PAResearchers about their weekly availability for research check-in calls, how many folks would help them answer research questions, and which methods (survey, interview, online research) worked best with their life responsibilities. PAResearchers kept a journal for their questions, reflections, and challenges. During that month, life happened! We had folks who had newborns, received cancer treatment follow-ups, experienced the unexpected passing of family members, and many life responsibilities that paused their research. Even so, PAResearchers consistently returned to their research questions and data collection. Often, the project director received excited text messages about an interview or a new website. Finally, in the collective analysis phase, we returned for two sessions to analyze data collection as a group and PAResearchers brainstormed recommendations and methods to disseminate their findings.

PAR sessions

Figure 2 describes our participatory action research journey, including steps to highlight community building, understand the coloniality of knowledge (Ake, 1979), and different methods to document community knowledges. Then, we moved into logistical strategies of refining research questions, determining methods, and documenting findings. In developing research questions, PAResearchers were asked to think about obstacles in their own wealth-building process. Research topics ranged from opening their own childcare center, knowing where to go for mental health support, starting a business, strengthening their teaching strategies to support children with developmental delays, and desiring support groups for saving accountability and financial literacy classes.

PAResearchers chose their research question and project as an opportunity to show the multiplicity in wealth-building across community needs. Across the PAR process, sessions are organized to have three layers – content sharing, alignment with PAResearcher needs, and planning for the next steps in the research design process. Conversations were communal, active, and drew on sharing practices that were common in our cultural communities. We sat in circles to talk and illustrate diverse methods of listening. We ate while talking and learned to engage in research as ceremony (Chilisa, 2019; Wilson, 2020). The research design followed methods that were detailed, organized, and drew on previous discussion. From these interactions, informal-feeling protocols emerged. Content topics included historical influences of research methods with Black/Latine communities, features of community-based research design, collective brainstorming, interrogating the distinctions across communal and academic knowledge, and refining methods that align with addressing key issues in research questions. Through consistently sharing and weaving personal experiences into activities, we connected specific types of methods in their communities today. We discussed theoretical frameworks underpinning research questions, ways of engaging with care, methods to collect information, and methods of analysis. We shifted meeting times, decided catering spots, and adapted types of incentives based on shared priorities. Developing trust required time to listen, care in responding, and intention to sustain values while cultivating relationships with PAResearchers.

Key Principles

Three principles were upheld across the stages of research: 1) sustaining PAResarchers as experts across the researching journey; 2) creating an adaptable research design; and 3) remaining accountable to the communities we touched. Each is discussed in detail below.

PAResearchers are Experts in their Experiences

Believing that the PAResearchers were experts in their experiences called the PAR program director to center their needs, voices, and concerns while making research decisions. In brainstorming the research design, the PAR program director considered one or two main research questions that each group could focus on. However, during the first session, this quickly went out the window as they discussed their passions in early care and thought about becoming financially secure. There were overlaps in who they wanted to talk with, but each PAResearcher took a different angle to answer their question.

Following their lead, the PAR program director adapted the research design to incorporate specific needs and account for individual—but collaborative—research projects. After each discussion session, the program director reflected on PAResearcher vocabulary, wrote participant observation ethnographic notes, and adapted discussion slides for the next session to incorporate these reflections. For example, many PAResearchers often said “research” or “the research” to describe their PAR projects. Guided by this, the PAR program director began to use that wording in discussions, summary reflections, insights documents, and NOLA C.A.R.E.S. collaborative meetings, as well. This was one way to weave member-checking consistency and adapt vocabulary to sustain PAResearchers as experts.

Creating Research Design that is Adaptable

Research design adapted to the PAResearchers’ needs for childcare, timelines, and needs in life. We developed a norm of asking about flexible incentives for self-care, childcare, and transportation. In the research design, the budget included childcare and could be adapted based on the number of children and provider recommendations from the PAResearchers. During our first week, one PAResearcher shared that she already had someone who watched her four-year-old child at the house. It was most convenient for her family—and especially their young children—to continue that routine because they had a long relationship with the provider. For other participants, we talked about the possible options. Examples include whether caregivers feel most comfortable with care in the same room with all the children together, multiple childcare providers at one time, or having the children stay at home and paying their regular provider. Thus, it was decided that childcare would happen in the space most comfortable for the child, their family, and their schedules. Some PAResearchers brought their older grandchildren with them to sessions to watch the younger children. Others kept their children at home with a regular caregiver. Adaptable childcare helped PAResearchers focus on their research projects in a manner most comfortable while including young children and youth in the decision making process. Researchers and community members co-created research timelines based on their daily life situations of PAResearchers. In research design, PAResearchers documented their findings and wonderings in journals and check-in calls with the PAR program director. Many check-in calls happened later in the evening after PAResearchers finished the work day. PAResearchers reflected with family members, co-workers and fellow PAResearchers.

Adapting the research design became an iterative and reflexive process of prioritizing the needs and desired direction of the participant researchers while holding the overarching goals of the project. We met in spots with local histories in education to expose PAResarchers to real-life examples of their reflections. Similarly to their training sessions, each check-in call informed the strategies for the next PAR session or gathering.

Researchers remain accountable to multiple communities

PAResearchers and the PAR project director were accountable to the many communities touched, including folks who shared their stories, time, and resources. During training, PAResearchers had extensive conversations about consent. For example, the ways they felt consent in deciding to join the PAR program, how their communities gave consent, and how PAResearchers wanted to experience consent moving forward. We discussed which communities PAResearchers touched regularly and how often. We brainstormed the range of ages and experiences that would give them an accurate representation of their research topic. We talked about shifting the imbalance of a historical dynamic where people who are “being researched” do not experience the benefits of community investment, specifically for Black, Indigenous, Latine, and other communities of color (Villenas, 1996). This was an opportunity to be inclusive and accountable in cultivating researching communities. We embraced the aspect of remaining accountable to communities. In previewing our findings, we brainstormed invitation methods that were welcoming, and which presentation styles would be easily understandable by a range of audiences. Some PAResearchers wanted to create online slideshows, some wanted to create tri-fold panels to display their documents, and others wanted to print flyers. They found ways to harmonize their personal comforts in presenting information with how best to visualize their learnings with a wider audience.

Stories from different perspectives

In the following sections, we share first-hand experiences of three women who identify as Black; 1) a NOLA C.A.R.E.S. PAResearcher’s introduction to PAR while developing a research project; 2) the PAR project director holding the power tensions in academic and community-based research design; and 3) the NOLA CARES project director negotiating the varying needs of a large collaborative. Together, we have a range of academic learning experiences, and specifically research experiences, in universities. We hold PAR in NOLA C.A.R.E.S. as a strong example of caring for ourselves and other Black and Latine women while upholding accountability in community-based research. These stories are a window into shaping a collective vision of research that sustains community voice through each stage of research.

PAResearcher: A story of Ms. Peggy, the Presenter

For the most part, my mind, body, and spirit was telling me this was a great opportunity: to give out knowledge based on what I know and do. The reality of my experience—it is so much more and bigger than I am. What do I mean? Prior to March 2022, when I was to present at the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi) conference in Detroit, I was presented with an opportunity to be a PAResearcher with Beloved/NOLA C.A.R.E.S. In this feature of the larger grant, I could research a topic of my choice. I, of course, chose a subject dear to my heart, “how to support children with developmental delays.” During the research, I decided on my data collection method and I chose interviewing educators. I gathered questions to be answered that I felt might support my learning as an educator. I thought this would better help reach and teach my students. From this process, other doors opened for me, like being asked to present live, sharing specific details of my project, and interviewing a fellow PAResearcher at the conference.

It was a “WOW” moment for me. I am honored, really there are no words to express my gratitude. I must say it requires work, I had to be committed. First, I had to have creative ideas and be ready to compromise. Most importantly, I had to be in agreement to work alongside others to get the desired results: a thoughtful and engaging presentation about community-based research. While presenting, I was somewhat nervous, but the vibe was peaceful, which helped me speak with confidence. I wanted the audience to take away the passion I feel about interviewing in a one-on-one conversation with questions and answer dialogue, the eye contact, the tone, and body language. It was a great feeling to share what I know while keeping the attention of the folks in the room.

This PAR journey included sharing my experiences with others, which lead me to find new wisdom as well as come out of my comfort zone. I had to know my topic, be confident in my methods and insights based on what I researched, be self-aware, passionate, and embrace teachable moments along the way. During the presentation at ABPsi, one of the attendees spoke about how researchers should use their own ideas instead of giving their ideas to someone else to utilize so that person can prosper themselves instead of making someone else prosperous. As an individual, a creative idea can open a door for that person to be able to have passive incometo maybe use their resources to help others in their community, such as helping with the food bank, donation for youth camps, or any charitable organization that seem desirable to their satisfaction. As I think about this experience, a quote comes to mind, “Responsibility is always a sign of trust.” I am ever-grateful to Dr. Odim and Dr. Swift for the relationship I have with them and the trust they have in me. I believe that before any sort of working together, trust is crucial in the relationship to maintain successful outcomes. For me, PAReseacher means Pulling out Authentic, Reliable, ESsential Affirmation (and) Collaborations (with) Healthy Efficient Results!

PAR Program Lead: A Story of Research Tensions—Hearing and Learning with PAResarchers

Our first PAR gathering. 4 p.m. An empty room, full of tables, bright lights, and a wall of glass windows. As food arrived, we moved the chairs around for comfort. Two women walked in, looked around for chairs, sat, and talked about the day. Quiet Spanish filled the room. After a few minutes, one of them, Reyna, looked over and said, “Yeah, we just finished training, so it might take folks a little to get here.” I asked, “Do you think we should start earlier or later from when the training ends?” “Hmmm, I’m not sure,” she said. “Well, maybe we could have the food arrive earlier and folks could take some time to transition from work minds to this space, I suggested.” Reyna and Zuymeys, another PAResearcher/coworker, looked at each other and nodded their agreement.

The next session started earlier so that people could come straight from work and eat. The first training session was an example of the shifts in research design to adapt to the needs, schedules, excitements and work responsibilities. Early in recruitment, a potential PAResearcher asked how this program would be different. She went on to describe meeting many organizations who wanted to hear their stories during election or voting seasons, but the community never saw any follow-up or action on their sharings. How would this program be any different, she asked. And how do we know we can trust you?

In response, we described our backgrounds in education and desires to engage in research differently, but I knew words would not be enough. I sat in the tension of being a researcher who looked like them but also held credentials, just like many past researchers who held transactional researching practices in this community. From that moment, I looked for opportunities to be transparent about my actions, hold care in interactions, and move at the pace of trust—a Beloved Community value. As the PAR project director, I felt the anxiety of harmonizing the urgency in our weekly NOLA C.A.R.E.S. collaborative meetings that wanted updates in deliverables and cultivating trust where there had historically been extractive and transactional research relationships. The bi-weekly check-in calls became a reminder to keep track of research progress, take moments to ground PAResearchers, and an opportunity for me, the program director ultimately responsible for the PAR aspect of the larger grant, to learn about everyday PAResearcher joys and struggles. This included things like: Did their monthly employer match come through for the savings investment?; Did they get a 15-minute break?; Which child made them smile?; and Which coworker was out sick? In these everyday moments of listening and learning, we developed a trusting research relationship. I returned to the PAR principles of trusting the expertise of the PAResearchers to stay grounded in the goals of cultivating community-led research.

NOLA CARES Project Director: A Story of several shifts: Mindset and Practice Shifts for Partners and Funders Working with PAR-centered Organizations

PAR asks partners, funders, and organizations to shift into mindsets of community-centered work that facilitate acceptability and buy-in and foster respect for the processes and practices in research design. This work requires that we shift focus from outcome-based and product orientation “business as usual” research methods that are usually extractive and may even offer deficit lenses of the communities of interest.[1] Several shifts that were identified and worked through with our funders and partners in order to align with Beloved Research practices and PAR as a viable method of research. The NOLA C.A.R.E.S. project director initiated several shifts to acclimate funders, recognizing their sense of urgency, bilateral exchange of information, and recentering Black and Latine ECE professionals in the goals.

(1.) Acclimate Funders, Recognizing their Sense of Urgency

Introducing the iterative and process-centered orientation of PAR into the product-oriented space of funders, evaluators, and even partners is an essential piece to managing the expectations of all shared interest partners. The process of PAR is participant-centered and flexible. These principles butt up against the need to have project deadlines and outcomes solidified and outlined in advance. What works well in terms of schedule and timeline, data collection, and dissemination will change and shift from cohort to cohort. Therefore, it was necessary to have deep conversations about the structure and process of PAR with partners, funders, and evaluators so that there is clarity in the process and product-focused expectations can be adjusted. For example, NOLA C.A.R.E.S. partners expressed an eagerness to glean information from our PAResearchers to inform policy advocacy and programming. There was an urgency to jump into planning, or just extend an open invitation for PAResearchers to join the existing grass-tops policy meetings, which is standard for most operations. However, the cadence of PAR centers the participants as owners of the timeline, where, when, how, and if knowledge will be shared and with whom. As our first PAR cohort was establishing a relationship with the program, they were somewhat reluctant to jump into relationships with our partners. There was historical and concurrent perceived harm that had been caused when research within the community was extractive (done “on” or “to”) rather than inclusive (done “with” or “by”). Consequently, there is an understandable hesitancy by most of the PAResearchers to join the grass-tops policy meetings that are led and attended by majority white participants.

(2.) Bilateral exchange of information

Trust had to be built and proven before this cohort was ready to engage deeper with our partners or authorize any knowledge exchange. Discussions with our partners about the processes of PAR helped to temper urgency. These discussions were bi-directional; as partners were introduced to the processes of PAR, we also noted we needed to be very transparent with our PAResearchers at the beginning of the engagement as to the purpose of PAR within the scope of the project, which was to exchange information with partners so that they could provide resources and align advocacy efforts. This is in contrast with the second cohort; mostly due to the deep relationship work forged with the first cohort, we had become trustworthy partners within the community and that relationship was paying forward. The second cohort welcomed grass-tops policy leaders within our collaboration into their space where there was an exchange of knowledge that will undoubtedly pay forward to future endeavors.

The exchange of information is another mindset shift that occurs when using PAR as a chief method of discovery. Information flows between the collaborators and the PAR participants. We see and acknowledge each other as information experts. Our partners and collaborators hold an incredible amount of knowledge on systems, policy, and advocacy. Our PAResearchers are experts on their own life experiences—the real, lived, and felt experience of the policies (or lack thereof) that influence their everyday lives. Therefore, both types of expertise can work to form an integrated and holistic approach to systems change.

(3.) Centering Black and Latine ECE Professionals

Many initiatives around Early Childhood Education (ECE) are focused on the young children served by the industry. One of the unique features of NOLA C.A.R.E.S. is that all efforts of the collaborative are focused on the ECE professional, specifically the Black and Latine, women-identifying people that power this industry with their skill, hard work, and passion. Centering the caregiver was, and still is, a mindset shift for partners who are steeped in ECE advocacy for the sake of the child’s development. Indeed, the inclusion of PAR in our initiative, which is completely powered by these caregivers, is a design element that is helpful in making that shift. One simple question that we always come back to is, “How is this (event, function, policy priority, action, program) centering Black and Latine ECE professionals?” This question of how we are centering our population of interest also leads to how we are including this population in decision-making and guiding internal processes that will affect them the most. Indeed, one of our most vocal and engaged partners is a Black, women-led organization that collaborates with ECE partners all over Louisiana to strengthen business practices for sustainability (see For Providers by Providers). Additionally, PAResearchers are given a (literal) seat at the table in our Policy Team and have been co- or primary presenters in conference presentations and papers. In this way, we shift the community of interest from being an external variable of our program to be observed and analyzed to being an essential arm and collaborator in our program.

Conclusion

The participatory researching process of participating, activating, and researching in community grapples with curiosities, excitements, and tensions of engaging studies in wealth building in Black and Latine women’s communities. This aims to inform the policy agenda and practices of NOLA C.A.R.E.S., a diverse, multi-organization collaborative. We leverage PAR methods to advance equitable and antiracist research, expose communities to abundant ways of thinking, and interrogate neutrality. PARresearchers’ day-to-day lives include significant stressors they face as educators, parents, women, and caregivers in the community. This highlights their dexterity in navigating many roles and deep knowledge in order to shift systems. Based on their research, PAResearchers have created workshops and gatherings in the community to share what they learned and expand the reach of research. There are also opportunities to join NOLA C.A.R.E.S.’ collaborative committees as policy advisors, committee ambassadors, or self-selected guides/participants in listening sessions. PAR, and the work with PAResearchers, remains the most rewarding and distinctive feature of the NOLA C.A.R.E.S. project. This work has challenged and shifted mindsets around what it truly means to center and value Black and Latine childcare providers. Our hope is that this work can flourish and continue to influence communities through sustained financial support. The ultimate goal is that current PAResearchers are independently encouraging another generation of PAReseachers, extending and building knowledge with, and for, community.

We at Beloved Community are committed to de-colonizing our language and terminology that has violent undercurrents. Therefore, we have intentionally replaced the term target population with community or population of interest.