Acknowledging the Trauma of Research in Black Communities

We, the authors of this paper, name the racial trauma of research and how using the language of research can elicit memories of harm, whether witnessed directly or not, in the Black experience in the U.S. In Harriet A. Washington’s (2006) book titled Medical Apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present, the author cites a history of “dangerous, involuntary, and nontherapeutic experimentation” (p. 7) committed against Black-bodied people between the 18th and 21st centuries. Black-bodied people in the U.S. hold memories of experiments conducted on their bodies, treatment withheld and denied, diseases and ailments misdiagnosed and underdiagnosed, and the extraction and exploitation of cultural knowledge, all under the guise of research. We acknowledge that research continues to advance the intellectual cannon associated with whiteness and Euro-centered knowledge dominance, which fuels the machine of the academy while rarely addressing or solving persistent racial inequities and injustice in the U.S. We snatch research back like a “bad sew in[1]” from the academy, reclaim it, and reimagine participatory research from a community-driven and liberatory lens. We lift forward the agency of Black women and the continued practice of envisioning worlds that embrace Black children in freedom and love.

Introduction

“Genius is a terrible thing to waste, but a glorious thing to cultivate” (Sullivan, 2016, p. 147).

When Village of Wisdom (VOW), a community-driven nonprofit located in Durham, NC, coined the phrase “protect Black Genius” in its 2014 founding, this was an act of social resistance and a proclamation of Black families’ healing to the world. To be able to cultivate and protect Black Genius is a radical and revolutionary act in systems that attack, diminish, and erase the voices of Black people (Jackson, 2016). The organization’s history began with conducting listening sessions with more than 150 Black families and parents and the development of its foundational Black Genius Framework, a socioemotional model that outlines six essential elements needed to create a culturally affirming learning environment for Black learners (Majors Ladipo & Jackson, 2021). The term Black in this paper is a descriptor used to encompass people of African descent and those that exist across the diaspora, those from South and North America, the vast continent of Africa, and elsewhere. The term Black Genius, uttered and written, elicits what Taylor Mary Webber-Fields, the Director of Parent Evolution at VOW, often alludes to as “dreaming up Black futures.” Since 2014, VOW has continued to infuse Black parent wisdom in its frameworks, programming, and education solutions. For VOW, protecting and cultivating Black Genius has been and will continue to be relevant to the past, present, and future.

In 2020, the U.S. tested the ability to protect Black Genius when the COVID-19 pandemic and racial violence left a downpour of devastation. VOW, like other Black-led nonprofits in the U.S., received rapid funding from funders to understand and respond to the COVID-19-related needs of their local communities. Before COVID-19 hit the nation, VOW’s staff began to think through new ways to invite Black parents into the organization as leaders and thought partners in creating culturally affirming learning strategies for educators. So, when so many Black children and parents found themselves confined to their homes, afraid and unsure about their future, schools, and communities (North Carolina Community Action Association, 2021), VOW used this time as an opportunity to learn more about the devastation of COVID-19 on Black families through a participatory research project that aimed to understand challenges and barriers to remote learning. This rapid response shifted the organization’s work with Black parents and led VOW to invite and fund five Black mothers to exit the reality of the double pandemic and participate in its first inaugural class of Black Parent Researchers. These parent researchers began to co-create the protocols for the focus groups and one of the authors offered a question she used in her own research with youth about their dreams and aspirations. In this preparation process, the parents and staff modified the research question to become: what dreams and aspirations do Black parents, students, and their teachers hold for Black children?

In the dialogue between those Black mothers and VOW staff, and through the interrogation of language like needs assessment, VOW gave birth to the Dreams Assessment. As these five Black mothers began to conduct focus groups, they witnessed teachers challenged by being asked to dream for Black children on one end and, on the other end, Black parents and children wanting to dream when the world around them shut down. By the end of 2020 and beginning of 2021, the collective genius of those Black mothers catapulted them into a movement of resistance against dreams deferred and into a space of dream actualization. We tell this story of an emergent model that evolved as VOW and those mothers began to reclaim research as community-driven and liberatory. The authors tell this story using a play on the words “Black Genius flexin’” to capture Black storytelling as visual imagery and text (Tolliver, 2022) and to demonstrate the value of positioning Black storytelling as essential to liberatory research and Black parent power-building. In the storytelling method, the authors embed the tradition of sharing the main characters, the setting, and lessons learned. The authors define the language of Black Genius, dream potentials, and Dreams Assessment to establish the primary argument that the Dreams Assessment can be a radical and reimagined approach to participatory research. As the primary curator of this paper, Dawn X. Henderson writes from the stance of first and third person and holds the responsibility of weaving the stories together. The authors offer collective lessons and invite readers to embrace this work as an opportunity to rethink their research practices.

Defining the Terms

Liberatory and Liberation

In this article, the words liberatory and liberation disrupt dominant traditions and ways of knowing and doing. Liberatory can be defined as the deliberate and intentional act of freeing oneself from oppressive systems, while liberation is freedom itself. Liberation entails an increased critical awareness of systems of oppression (e.g., racism, classism, or colorism) and the engagement in acts that address and dismantle these systems under the presence of healing (E. A. Turner et al., 2022). The Black community’s ability to heal from systems of oppression is what Regina Mays, one of the authors and Black mommas, shared as an ability to build new systems. Liberatory practices are intentional acts of resistance to racism and involve building new systems of freedom and love. The spirit of self-determination and the act of social resistance deafens the sound of Black inferiority with loud voices and writings that bring Black Genius anywhere in the U.S. VOW’s proclamations of Black Genius are liberatory practices that do what Bryant-Davis and Moure-Lobbon (2020) describe as reclamation, the exercise of agency, and the expression of purpose. Our liberatory methodologies involve reclaiming research and the use of storytelling to embrace Black self-love, healing, and care in a system that tells you otherwise (Bryant-Davis & Comas-Díaz, 2016).

Black Genius

In truth, there is no absolute definition of Black Genius. Often, when Black parents and others are asked to define Black Genius, individuals may respond with ancestral names, the names of Black political activists, and so much more. VOW defines Black Genius as “the ability to create new systems of equity and justice and/or moments of liberation… the ability to dismantle and resist systems of oppression and injustice” (Village of Wisdom, n.d.). In Harvell’s (2019) description of Black genius, the author notes how this genius is the open recognition of the collective survival of Black people against systemic atrocities. Too often, Black existence is about the survival associated with the atrocities of racism. In this paper, Black Genius is not about survival; instead, it is the genius of Black people’s existence beyond racism and enslavement. It returns to the knowledge of what Feagin (2015) argues was evident in African institutions, ideologies, and spiritual practices before enslavement and colonization. Black Genius is reclaiming and retaining cultural practices, despite being subjugated to systemic violence aimed at erasure and eradication. Black Genius is evident in the fabric and stitching of the U.S. and the myriad ways Black culture has shaped the political structure, education, music, and art in the U.S. Black Genius and Black Genius flexin’ denote an embodiment and a loving embrace of a cultural ethos of movement, expression, art, and resistance through language and knowledge. The subtleties of Black vernacular English are represented in the language and the lived experiences of Black mommas centered as expert knowledge in this paper.

Dream Potentials

Black people often exist in parallel worlds, one that is real and one that is imagined (Kelley, 2002). Dream potentials stem from envisioning liberated futures and liberated futures pull from a past and present legacy of collective organizing and freedom-seeking across the Black diaspora (Butler, 2020; Fairley, 2003; Kelley, 2002). Dream potentials involve refusing to accept the terms of the world as it is or as it has been decided for Black people (Butler, 2020, p. 37). Black people construct new worlds where they “dream of Black futures” to counter the realities of racism; at the intersection between the imagined and reality lie dream potentials and the expression of Black Genius. For example, Black parents flex their dream potentials when they dream up neighborhoods and schools where Black children roam freely, access love freely, and where others value and affirm their cultural identities and expressions (Barrie et al., 2021). Black Genius flexin’[2] in this paper is the readiness to do what Young (2021) argues is “working for the future in the present and believing the future is now” (p. 430). Despite racism, Black people, under the vision that the future is now, have manifested their dream potentials in a continuous journey toward justice and freedom (Butler, 2020; Kelley, 2002).

Dreams Assessment

The Dreams Assessment is a community-driven model that emerged as an approach to assess dream potentials and a catalyst for actualizing those potentials into actions (Barrie et al., 2021). Harvell (2019) describes the critical analysis and interrogation of current systems followed by reimagining new ones as central to Black genius. A reimagined approach to participatory research meant VOW interrogated the language of needs assessment. Traditionally, needs assessments use a top-down process that allows those who exist in social structures of privilege (e.g., white, affluent, heteronormative, higher education, and elite institutions) to perform assessments on communities where those communities rarely take control of decision-making (Sankofa, 2021). Joy Spencer, one of the authors and Black mommas, recounts how people just wanted to dream about a future during a time when they could not leave their homes and bore witness to the repeated murders of Black people. She shared, “Out of the chaos and destruction of the pandemic birthed a vision…” (Meeting, 5.24.23). Dr. William P. Jackson, the Executive Director of VOW, recalls how the Dreams Assessment was necessary for the organization to leverage Black parent power in a system that was not designed for Black parents and Black people to have power over it.

We Gonna’ Do Black Storytelling: Our Methodology

The methodology imbued in this paper is storytelling as an embodied practice (De Medeiros & Etter-Lewis, 2020; Meitzenheimer, 2020; Tolliver, 2022). We use storytelling to share the setting, characters, and plot behind the Dreams Assessment. Tolliver (2022) writes that storytelling frees Black people from the “methodological cage” of a white-dominated field of generating and producing knowledge. Black people reclaim research through storytelling. Storytelling weaves experiences together through communal sharing and evokes collective power by creating alternative realities (De Medeiros & Etter-Lewis, 2020; Meitzenheimer, 2020). Storytelling elicits presence and emits messages of, “I am here, I am present, and you cannot erase me,” despite the erasure and silencing that often happens for Black people and Black women (Thomas, 2021; J. D. Turner & Griffin, 2020).

We use the prompt, “What had happened was…” developed by VOW’s Director of Parent Evolution, Taylor Mary Webber-Fields, to narrate the plot and emergent findings from conducting the Dreams Assessment. In storytelling, visual and textual imagery (Maragh-Bass et al., 2022) aims to do what Lenette (2022) describes as “challenging established, dominant, colonialist research paradigms” through communal weaving. Communal weaving and liberatory methods thread stories together through images, structured and unstructured text, and poetry to honor ancestral veneration (Gates, 1987). I, Dawn X. Henderson, serve as the primary curator of the narratives, writing from the standpoint of first and third persons and working to decenter individuality and instead center communalism.

Where 'Dis Take Place: The Setting

VOW is housed in a former school that once educated the segregated bodies of Black children in Durham, NC. Durham County is one of the five most populated counties in North Carolina and continues to celebrate its rich history of strong Black cultural ties and viability (e.g., Black Wall Street-Hayti District) amid the presence of gentrification. A persistent opportunity gap resides in the county of Durham, where Black families have been displaced and pushed out through gentrification and the increase in housing costs (De Marco & Hunt, 2018). Additionally, the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights (2017) reported that the school district’s reliance on discipline in the form of suspension, expulsion, and law enforcement referrals has disproportionately resulted in Black children missing more days of academic instruction in comparison to their peers. In 2020, VOW existed in a community space caught between imagined viability and the magnified devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic. In North Carolina alone, women represented 49% of deaths associated with COVID-19, with Black women accounting for 30% of those deaths (Thompson et al., 2020). In this setting, the Dreams Assessment happened with interviews with Black children, their parents, and teachers of Black children in the world of Zoom, in Durham, and across other counties where Black mothers traversed southern terrains.

Who We Is: The Characters

Our stories emerge from a critical analysis of how we see ourselves, how the world sees us, and the contexts we interact in. We acknowledge that we are characters in a story about who we are and our relationship to the expectations and actions found in the systems we occupy (Berry & Cook, 2018; Connelly & Clandinin, 1990; Nygren & Blom, 2001; Simons, 2009; J. D. Turner & Griffin, 2020; Wells, 2011). We are the five Black mothers called into the Dreams Assessment, Courtney McLaughlin, Denise Page, Joy Spencer, Nadiah Porter, and Regina Mays, and the two researchers hired by VOW, Drs. Rabiatu Barrie and Dawn X. Henderson.

This is where I, Dawn X. Henderson, the curator of our communal story, share how I entered this work. As the primary curator, I entered this work still carrying the residue of my time in the academy and being in a higher education institution that was historically and currently persistently white. My training is in Community Psychology, and I have been doing community-based, participatory, and action research for more than a decade, with limited experience doing community-driven research. I want to acknowledge how, as a Black girl, I learned to be quiet and silent quickly because the adults in my life could not deal with me and the grief and mourning I held in my body. Thus, writing and drawing are expressions and extensions of me.

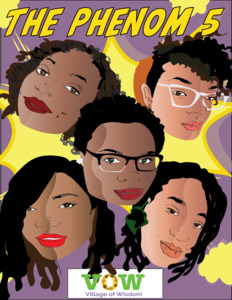

When I met the five Black inaugural mothers, I saw them as the furious and phenomenal five. I remembered all the comic books and the karate flicks I watched in my younger years and asked, “Where are the Black-bodied people?” In Figure 1, I illustrated the phenomenal five as a tribute to them and as a representation of Black women in this world. They inspired me to tap into my creative self and draw them through the eyes of superheroes. I entered this work after being granted permission by the co-authors to weave their stories together; I weave these stories with the audacious tasks of co-editing with them not to minimize our expressions but to honor the concept of limited space. I take this time to mention the other Black women who did not make it into these pages: Aya Shabu, Amber Majors Ladipo, and a Black man, William P. Jackson, who comprised our village and brought forward their genius into this work.

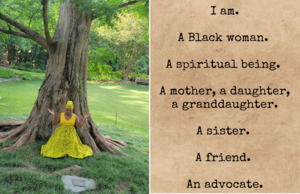

When we asked ourselves what identities we bring into this work, we acknowledged that self-identified, Black-bodied women dominated our communal body. We see ourselves as daughters, descendants of freedom fighters, Black nationalists, and Black Genius protectors. Denise Page shared, “Definitely a Black woman first, I identify as a mother, sister, daughter, passionate and protective about Black children, Black people and Black issues.” In her greatest strength and modality, Denise offered much of her reflections as illustrations seen throughout this paper in Figures 2, 4, and 6-9.

Nadia Porter wrote, “I bring with me the identity that is mostly uninvited, and unseen in research and platforms and institutions. And that is ‘Mama.’ Not mother, but Mama. Understood across cultures. Endearing. Familiar. Empowering and impactful. Mama. I am grateful that the mama in me can not only move freely through this work but lead it.”

Joy Spencer’s reflections further center the salience of Blackness. She shared, “I am a Black woman, mom, parent, advocate, and community leader.” In her own reflections, she writes, “I carried all of my identities and the perspectives that came from my experiences to guide my work and the empathy I brought to the parents and students we spoke with.” Rabiatu Barrie, also known as “Rabi,” was a research consultant. She tells her own story of coming into this work as the sixth and final child born to well-educated Sierra Leonean immigrants and coming from a place where she had to fight. She shared:

I was raised in the suburban south where my Blackness, my deeply rich, dark brown hue, my direct connection to The Continent were forced into my awareness by the time I was 5 years old… [I went to] well-resourced schools that provided rigorous academic curricula. So, all my siblings and I attended private schools. It was in my all-white private school that I learned to fight, to advocate, and push back against racism and violence against my then small Black body that housed a beautifully genius Black brain… The only way I knew how to fight was to beat them with my smarts and beat them I did, but it was a heavy burden to bear. It was a burden that I carried for my entire K-12 education, learning in anti-Black school environments. It stifled my genius. Every day I showed up, not to learn, but prepared to fight for my humanity. The desire to do what my ancestors and elders had done for me, make a clearer path toward liberation for those who would come after me brought me to this work. I came with vivid memories of how school systems can act to stifle the brilliance of Black children and how Black parents, kinfolks, and communities act as a shield from the spears of American schools.

Regina Mays poetically states how her Blackness, her womanhood, and other identities shaped her experiences and how she entered the work.

Courtney McLaughlin’s reflection speaks to the poetic cadences of Nikki Giovanni, Maya Angelou, and all those other Black women who write through prose and rhythm. Throughout this article, we acknowledge our Black-bodied selves. In writing this paper, we had to recognize that as women, as Black-bodied people, we exist in a system where writing can be laborious when we must also show up for our families, our jobs, and our communities.

What Had Happened Was: The Plot

VOW did not begin this work with the name Dreams Assessment; according to the women in this story, it emerged like the myriad ways Black culture eases its way into the fabric of the U.S., actualizing our existence beyond systems that dehumanize us. Joy writes:

I remember the title, Dreams Assessment, came later in the work. At first, we began by asking key questions to explore how we could feel the pulse on what Black parents, students, [and teachers] were experiencing during the pandemic. What we discovered was a list of desires and dreams.

The early seeds of the Dreams Assessment began with previous connections, relationships, and friendships across VOW staff and the Black Parent Researchers. Before the Dreams Assessment, Dawn and Rabiatu participated in leadership fellowship programs under the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation with William, the Executive Director of VOW. Taylor Mary, the Director of Parent Evolution, knew these Black mothers from VOW’s programming called Family Learning Villages. In her own reflections, Courtney writes about this journey or stream that began long before 2020. She shared:

My stream into the Dreams Assessment was like a continuous conversation. Sister Taylor-Mary was a reflective partner to the community work that I was doing at the time. In the spring and summer before the Dreams Assessment launch [in 2020], I would be in a reflective/activation space with Taylor-Mary and they would guide me through all of the ways my environment was telling me “NO” to help me see all the ways it was telling me “YES.” VOW was my “YES.” It was a confirmation to me that I was someone to believe.

The emergent Dreams Assessment happened while people across North Carolina and the nation were dealing with COVID-19. In Nadiah’s reflections, she shares not only what she and many families were struggling with in the U.S. but a need for a positive distraction:

At the start of the pandemic, my family, like other families, was sort of drifting by and only partially navigating education during COVID. And even those of us with the most keen sense of smell for discrimination had gotten lulled by the way things are and distracted by the need to survive. While being distracted by survival, some of us, (certainly me especially) neglected to challenge systems and practices. Operating as if the status quo of inequity in education during this time was acceptable. The Dreams Assessment took away the “distraction” of survival and reminded me that shit wasn’t right before, and it still ain’t right. The Dreams Assessment gave me a clearer lens by which to see, and a new arm by which to fight.

The five Black mothers had less familiarity with participatory research, yet in 2020 they found themselves called forward to conduct research with VOW. Some of the mothers thought doing research, at the time, was out of reach for them. Denise shared:

It actually, it was out of reach for me. I felt like I didn’t have the knowledge adequate enough to do it. It felt like a challenge that I was not going to necessarily complete… when you think of research, people go to school for research and you don’t think everybody’s a researcher anyway, I did not have the academic credentials and time to be a researcher.

Her perceptions about who could do research made her feel like she needed to have adequate credentials to conduct the work. She further explains, “Courtney helped me, and VOW trusted me. VOW trusted me in my expertise as a fact even when I did not see my expertise.” Denise’s involvement in the Dreams Assessment contrasted with a socialized belief that community members cannot drive research and is only done by people holding PhDs. Rabiatu, the research consultant, reflected on how she came into the work, her responsibilities, and the value of being surrounded by Black people:

I came on to the project as a research consultant. My job was to lead the implementation of the research project that the VOW staff and parent researchers designed… I also produced a report on the analysis and interpretation of the results with cocreated recommendations for school administrators and policy makers. What I remember and appreciate most about my time consulting with VOW was all the Black staff and our very Black staff meetings. Weekly we met to conduct business, but it never felt like work. It felt like family getting together to push forward important work while telling jokes, bantering about popular culture, sharing family stories that we all could relate to. The meetings did not follow convention of Robert Rules of Order, but business always got done and work tasks always completed.

The work involved devoting time and spaciousness to caring for the women in this work and their families. The Dreams Assessment involved late-night and early morning phone calls, morning and afternoon drives, impromptu dance-offs, and communal wellness sessions to release the anger of hearing a white teacher say, “The problem with Black children…” in one of the focus groups with educators. Joy shared how conducting the research was not just about creating spaces for Black families to dream but for them to dream in a space of healing and care. She wrote:

We experienced grave challenges in real time, same as the people who were participating in the focus group. Some of the things that were said really hit home, some were offensive, some were CHURCH. We had to take time to debrief from each session and re-ground ourselves. This wasn’t a run-of-the-nill research topic that we were disconnected from, we discussed issues that directly impacted our lives. I remember having to take deep breaths and walks after some of the focus groups… we, as facilitators, were experiencing the implications of the pandemic while trying to assess them in our community.

Courtney, like the other mamas, talked about the value of being seen and heard as a Black woman. She talked about how they were collectively seen as Black parent researchers and how they were, in turn, making sure Black children and parents in the focus groups were seen and heard.

Designing Protocols and Spaces to Ask Questions and Listen

The focus group protocols were intentionally designed to give voice to the dream potentials of Black children and their parents. The Parent Researchers co-created the protocols for the focus groups and refined the questions. They were asking questions while also answering some of their own: Can I do this? Yes, you can. There was a boldness in asking the question: “What dreams and aspirations do you hold for Black children?” The parents were asking their community to activate their dream potential, inviting participants to step away from the pandemic and away from seeing Black children as less than others, as missing something, and to instead see their future. In setting up the focus group protocol with the parents, I, Dawn, introduced the parents to a set of Touchstones (Coming to the Table, n.d.), and they wanted to use the Touchstones in the focus groups. One of the Touchstones reads:

Listen intently to what is said; listen to the feelings beneath the words… Listen to yourself also. Strive to achieve a balance between listening and reflecting, speaking and acting.

There was a careful balance between interrogation, asking questions, and listening to the “feelings beneath the words” in the Dreams Assessment. Courtney reflects on how they began to interrogate research practices and, in facilitating focus groups, developed a new way to ask questions. She shared:

I facilitated the space with Black parents and educators of Black youth. While nervousness existed, I remember that we had been well-prepared for the assessment. We were reminded that we were already researchers by nature and, for me, this was a continuation of broad community conversations that were happening across our trusted networks. I remember building out the protocol for the focus groups. I remember the intentional placement of the touchstones. We want to create a container where all truths can be held—even the ones that made us uncomfortable. I remember the importance of placing pauses for check-ins because we knew participants were actively living in the realities that they were reflecting back to us. I remember calling forward the ways participants were finding joy and hope in their experiences. I remember approaching this with the understanding that answers and solutions (or at least the pathway forward) were already amongst the story-bearers and our task was to set the place and space for the right questions to be asked.

Listening emerged as a skill used in the focus groups and with one another. Regina shared, “I choose to listen outside of my own opinion though there were many similarities each experience of others held its own place value. I strived to help create a safe place for other Black folk to be transparent and vulnerable so we can create the changes we need (ed).” In Figure 5, Regina shares a picture of receiving, giving, and listening.

In her own reflections, Nadiah expressed that listening during the Dreams Assessment was challenging, yet she was able to strengthen this skill. She wrote:

I remember one of the greatest challenges was listening, as opposed to responding or relating. I’ve participated in “active listening” exercises before, but it’s different when you are conducting research. I was a first-time researcher. We, (researchers) were prepared well by Village of Wisdom, and we were well aware going in that this was not a space to talk, but to listen. And I remember thinking, “If I interject my thoughts or opinions, I will compromise the integrity of the research.” Furthermore, I remembered learning how the integrity of some white-centric research has been compromised intentionally. And how data has been skewed or omitted, especially when the outcome impacts my people. And so, I asked the questions we were authorized to and had to ask. And I shut the heck up, for the integrity of the information, and for the culture!

Denise shared a similar reaction. She acknowledged that her desire to interrogate folks, as she calls it, “the nosey neighbor,” does not always put her in a place to listen deeply. She said she learned to listen differently:

I was asking questions to people, and I learned to interrogate differently, I learned to lean into what is said and not be reactive. I learned to making meaning around like what is said, what is meant at the same time. I was digging deeper into what is actually said.

Doing the Witnessing and Perspective Taking

Witnessing is a personal or direct observation of something or someone, steeped in affirmation, valuing the other, and releasing power (Alexis, 2021; Stein & Mankowski, 2004). In data collection, we witnessed how Black children, their parents, and teachers experienced challenges in protecting Black Genius. The act of witnessing began to inform new perspectives and corroborate previous ones. Denise shared gaining a different perspective of other Black parents and the challenges teachers experience when protecting Black Genius. In Figure 6, she illustrates the brick wall of schools and young people declaring their Black Genius as they attempt to walk into the schools. She shares:

…As a parent like we trust the teachers to protect our kids, and I could feel that the system is set up not to allow teachers to protect our children and for us [as parents] to act a fool because you don’t protect our children. The frustration is not just about the county you are in, but we all are going through similar things when we trying to protect Black children… it is the same frustration, and no one wants to hear this. Like we are all sitting in the same spaces and we carrying the same burden when it comes to our children in school. As a parent just listening to the other parents [in the focus groups] and seeing how they don’t lean onto the school and building their own villages outside the school opened up my eyes.

Joy and Regina shared their own realizations; some were new, and some were confirmed based on their previous knowledge regarding how the education system responds to Black children. Joy wrote:

…Realizing how teachers see parents and parent involvement and also how students view themselves and their role. I am a parent and the parent perspective really resonated with me, but it was amazing to learn from other perspectives. It also really affirmed the importance of having community-led, culturally appropriate assessments. We gained a wealth of knowledge from people that I do not think would have otherwise been represented in COVID-related social research… I learned that our children embody the responsibilities awe place on them (adultification). I learned that teachers think absent (working) parents do not care about their child’s education. I learned that Black students begin to feel how different they are treated from white students at a very young age.

Regina shared:

I saw how our students recognized that teachers don’t look like them as therefore it’s hard to understand them as students. Especially the desire for Black males to see Black male teachers; they [the Black children in the focus groups] wanted to know our history past Rosa Parks and they are willing to do the work, but they are afraid of becoming the next Sandra Bland, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd.

As parents and as adults, we were also bearing witness to young people, to the Black children in those Zoom spaces. The findings revealed that Black children have a desire to do well in school and to see their dreams come true, yet they carry a tremendous weight in their attempt to be successful in school while also being fearful for their lives.

Using Meaning-Making in Data Analysis

To support parents in the data analysis and dissemination stage, the research consultants introduced meaning-making to analyze and translate data into meaningful findings that led to recommendations on how the education system responds to Black children and their families (Barrie et al., 2021). Making-meaning is necessary to any story and is fundamentally at the core of storytelling. Individuals make interpretations, assign value to what matters, and translate experiences into symbols and words to convey meaning (Luitel & Dahal, 2021). Meaning-making unravels social identities, lived experiences, and beliefs into statements, inferences, and conclusions. Rabiatu mentioned how she guided the parents by looking at quotes and generating themes and recommendations for schools. In her reflection, she alluded to the dissemination phase of the work and her own “ah-ha” moment. As a researcher, she too had been primarily trained to do research less informed by the community and largely informed by the academy and the theories and frameworks within. She wrote:

The greatest ah-ha moment was during the interpretation and dissemination phases of the project. I was impressed, not in a surprised or ignorant way, with the mother’s deep reflection and insightfulness with regard to how to understand the responses of the stakeholders and the implications for them. The solutions they provided were top-tier. The ah-ha, or confirmation if you will, was in the necessity of community collaboration in this work. The people closest to the phenomenon will always have the best solutions. We in the academy can never lose sight of that if we want to do this work well.

Courtney shared similar sentiments about the dissemination phase being one of her greatest “ah-ha” moments.

I believe the greatest “ah-ha” moments arrived to me in the dissemination phase of the Dreams Assessment. Everything up to that point felt like a continuous conversation. Dissemination felt like I was starting a new conversation. It was a terrain where I was not always clear where “YES” and “NO” were resting. I remember experiencing the “Nos” [from those who] were slow to believe and quick to dismiss. I remember the “Yeses” that were invested in “what’s next” and “how can I help.” I remember this being an activation to the Dreamandments. In order to fully honor the stories shared with us, we knew it was important to not just hold them in a report but to activate them into actionable steps and collective demands. This was my “ah-ha” moment because it was when I realized that we were not interrogating this environment just for the sake of knowing but rather for doing. We were not going to patiently wait for these Dreams to dissipate and we were going to continuously endeavor to make these Dreams a lived reality.

Meaning-making extended beyond data analysis and involved asking what do we do with these meanings. The parents asked VOW what was next; what happens beyond sharing the findings from the Dreams Assessment? Nadiah talks about how the process of doing something with the data created a sense of trust and a knowingness that VOW would be responsive to what they witnessed.

I remember feeling… trust. I trusted the process, immediately and undoubtedly. I trusted the process because the organization leading the research was Black, and because the other researchers were Black. I trusted that the purpose of the research was not only to put a spotlight on issues, but to ultimately find solutions for them. The seeds of research were planted by us. The results of the research were watered by us, as we did the meaning making. And it was us that would bear the fruits of change. The research wasn’t just done by me, but for me. For my children. For my children’s children who would reap the benefits of whatever change would manifest.

'Dis is Way Different and Emergent Learnings

We acknowledge that the Dreams Assessment, like our approach to this article, is radically divergent from the traditional ways we have approached research and even participatory research to some extent. Schostak and Schostak (2007) argue that research is the most radical when it no longer keeps those in power powerful and when it transforms conditions leading to problems. Through our storytelling, we demonstrate how research can embrace a different way of being, thinking, and seeing, and this demonstrative act requires a disruption to traditions and pulling new ways of being out of the margins (Luitel & Dahal, 2021; Thomas, 2021; Tolliver, 2022). The very notion of turning a community’s dream potentials for Black children into action is a radical exercise of social resistance and Black Genius flexin’ in a world that attempts to oppress such freedom and delegitimize Black-bodied storytelling. The inability of others to embrace these other ways of knowing was most evident when it was time to share the findings from the Dreams Assessment with education leaders.

They Still Didn’t Believe Us

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, the dominant narrative strips away the collective humanity of Black communities. Consequently, those in the Black community—and even Black researchers in the academy—find themselves interrogated by a system that denies their truths and ways of knowing (Tolliver, 2022). VOW decided to share the research and findings from the Dreams Assessment with invited educators and school leaders across three counties in North Carolina. Some leaders seemed rooted in disbelief and desired more objectivity and numbers. Courtney shared this reflection:

I remember during one of our dissemination sessions, a school district leader inquired about seeing the “stories” but not the “data”… the way each one of us came off the mic with the might of every story we were entrusted with, I knew they weren’t ready. Dr. Rabiatu provided a collective summary all of our responses at that moment, “The stories are the data. When the stories change, the data has changed.” This was a moment of reclamation for me. An unapologetic moment for us to collectively deny those that were set upon denying the dreams and aspirations of our community…

Courtney coined the hashtag #BelieveBlackWomenTheFirstTime after dealing with those who wanted to deny or refute the findings of the work. Denise expressed feeling that some school leaders distrusted the findings, despite the Dreams Assessment adhering to a rigorous research process.

“We saw that you don’t want to trust Black people’s voice, it is always a pushback when Black folks say it,” Denise said. “A white male or researcher comes forward and you do not question them. When it came down to those in power, teachers, administrators, it was a test of how do you really know… Our work is tried and true, we went through a process of research and adhered to the same processes…”

On one side, our community embraced the findings, and shared their own personal anecdotes and experiences that corroborated the findings further in the Dreams Assessment, and on the other side, some people wanted to deny the evidence and refute the findings. Despite this presence of “not believing us”, we all believed each other, and other scholars further confirmed the findings in post-COVID-19 reports (North Carolina Community Action Association, 2021; Thompson et al., 2020). We held our truths and the truth of our community as evidence while people in the broader education system struggled with it. Some folks will experience dissonance and discomfort in embracing alternative truths, particularly when these truths of the world come through Black-bodied knowledge. Nevertheless, the lessons we carry forward guide how others may engage in radical acts of research.

Reclaim Research

The Dreams Assessment allowed us to reclaim research under the protective arms of Black mothers and through the work of VOW. Denise shared, “I learned that I did this already, this research thing, without the lettering. I have been doing research and this is naturally who I was.” We did reclaim research, snatched it “back like a bad sew in”, and underneath revealed a cultural ethos where Black-bodied people and women are heard, valued, and seen. At the core of the Dreams Assessment is a radical act that extends beyond traditional definitions of participatory research and the relationship between the academic and community (Black & Faustin, 2022; Rodriguez Espinosa & Verney, 2021; Rose, 2018). Other scholars like Mosurka and Ford (2020) noted in their analysis of participatory research that most findings generated from the research often reproduce inequities versus changing them. That is not our aim. The Dreams Assessment led to reclaiming the lived experience of Black people as valid and resisting the methodological cage of thinking, believing, and acting in ways that delegitimize Black-bodied ways of knowing. Rabiatu, now a faculty member at a Research I institution, shares her own interrogative practices and what emerged as a lesson in this work:

My biggest lesson about myself was seeing how deeply ingrained the Western way of conducting research was in my professional operation. I have always thought of myself as being deeply committed to community-centered, engaged, and led work. But I often had internal anxiety or distress at what I considered many layers that it adds to the process. I acknowledged and managed it through openness with the team. It was amazing to be able to talk that through with other Black people invested in the work. There was no place or space for shaming one another or questioning of competence for expressing my authentic experience. The village was for all of us, not just the families. Whew. It was career-changing.

Healing and Love Can Exist

Our retelling of the story demonstrates that Black love happened, healing happened, and educators and parents of Black children were left with solutions rather than more problems. Courtney mentioned how healing emerged through just dreaming, and dreams heard. She writes:

As abstract as this may sound, I learned that there is healing in dreaming… There is healing in honoring your dreams and making them a reality… there is healing in sharing your dreams and that your dreams are worthy of belief and action.

Regina shared how the Dreams Assessment allowed space for others to deal with those systems that harm them and to heal. In Figure 8, her picture invites the community into these healing spaces. In the Dreams Assessment, we created memories where research affirmed Black bodies and where Black women could be their full selves. Rabiatu’s reflections center on Black women and articulate how love emerged as a radical act in the Dreams Assessment yet a necessity to combatting systems of oppression. She shares:

The ferocity with which they [the Black mommas] love and protect their children was palpable in every meeting, even though the Hollywood squares of Zoom. They were willing to go to bat in every arena to make sure their children’s geniuses were honored, respected, protected, and nurtured. Their thoughtfulness and consideration and advocacy for not only their children, but other Black children, was remarkable. By the end, if I didn’t know before, I was absolutely certain that Black folx have the solutions to our own problems, that Black Genius is inherent in our DNA and way of life. The systems that have been built to systematically oppress us have been successful in many ways, but is also being systematically destroyed. Not by hate, but by love, radical love. Radical love that Black mothers wear as armor in their fight for the protection and nurturance of their children’s geniuses."

Community Power Building

Community power emerged while conducting the Dreams Assessment and disseminating the findings. Joy’s own analysis revealed how our communal power showed up in not only our presence as Black women but also how we had to negotiate different spheres of our lives to do the work:

Black women showed up and showed out! We combined our genius to execute successful training, focus groups, and summaries of what we learned. We rearranged our schedules and our children’s routines to ensure we could show up and be present for others, despite what we were experiencing in our own lives as we navigated a global pandemic and aimed to keep our little Black boys and girls safe. There is Power in continuing to show up for the community while also needing all of your energy to show up for yourself. That is a full display of Power.

Denise reflected further on the dissemination phase of the work and discussed the presence of communal power. “”…when it was time to disseminate our findings to schools. Everybody did their dissemination [to schools], each of us showed up and we showed up in the background to support each other… I saw Courtney, then Joy, then Rabiatu, and then Regina go in, and I was like yes, Black women got the power!"

In this communal weaving of our stories, we do not replicate and perpetuate knowledge that generalizes stories of inferiority, deficits, erasure, and disempowerment; rather, we share our knowledge and offer a roadmap for how to take back power from oppressive systems.

Continuing the Work

The Dreams Assessment was a catalyst for a movement in VOW and the continued curation of Black parent wisdom into solutions that transform educational inequities. In Figure 9, Denise’s illustration capture the presence of roadblocks and the ability to continue the work initiated through the Dreams Assessment. VOW continued to engage other Black parents in their community-driven approach. For example, VOW worked with another set of Black parents to create culturally affirming learning strategies for educators and parents—the Keep Dreaming Toolkit. VOW translated findings from the Dreams Assessment into digital assets (e.g., short videos and infographics) used across social media to increase engagement with Black parent wisdom. All the authors in this paper presented at conferences, gained new employment, and became permanent employees at VOW as well as entrepreneurs. When thinking about how the Dreams Assessment continues to live on in communal work, Courtney wrote:

The Dreams Assessment continues to live throughout the work of VOW because we never discontinued the conversation. VOW activated the Dreamandments when others were still “hemming and hawing”… I see the Dreams Assessment beating throughout our local ecosystems as communities awaken to the realization that the people hold the answers. This assessment can exist wherever dreamers exist. For real, I can see a Dreams Assessment utilized to address workplace solutions, to mapping out effective learning programs, to improving access to health systems, etc. I see the Dreams Assessment as a means to establish liberatory practices in all places, institutions and systems where the Dreams of Black communities have been burdened by oppressive practices and harmful behaviors.

Nadiah recognized that anchoring research in the deep desire to protect Black children means that you continue to hold this responsibility:

I believe that the Dreams Assessment and the process of engaging moms as researchers deepened VOW’s need for and understanding of research that is not only “based in” but “driven by” the community. I will make a blanket statement and say that there is nothing that moves/inspires a mama, and in particular a Black mama, more than ensuring the wellbeing and safety of her child(ren). With that in mind, there were no better researchers to drive the Dream Assessment.

Like Nadiah, Joy alludes to a community-driven lens as integral to creating responsive actions:

We went back to the foundational attributes of the words, community and participatory. This means that the bulk of the work transpired behind the scenes as we made sure to practice what we preach and first build a cohesive culture of community as a team… We prioritized proximity and loved experience to implement empathy and compassion—two things most research projects lack. Some may call that bias, but we recognize the expertise and genius that stems from experience. We do not need for people outside of our community and culture to observe and draw conclusions about our behaviors and experiences. We are perfectly capable of collecting stories and data from our own communities and assessing the feedback in order to be responsive to needs in our schools and neighborhoods.

The Learning Carried Forward

So come and take a walk and peace

There’s all the freedom you need

And go spread your love

For the people’s greater needs

All the Freedom You Need–Tarin Ector, 2021

Above in these lyrics shared by Regina, Tarin Ector (2021) references coming together, including love and responsiveness to the people as essential in practicing freedom. Such references, we argue, are essential to research. Smith and colleagues (2015) further reference R&B songs and communalism and interdependence as culturally responsive principles in community-based and participatory research with Black communities. The lessons carried forward, and the implications of this work are manifold. For one, we had to reclaim and redefine research as an embodied practice of protecting Black Genius. Protecting Black Genius necessitated a response to a communal call of refusing to allow dream potentials to die or to be deferred. Together, we actualized the dreams into actions and produced evidence to equip parents and educators who protect Black Genius to continue the work. Second, we aimed to see Black women, our loved ones, our children, and the community healing, loving freely, and being affirmed. We argue that a radical approach to participatory research is healing and can be an exercise of social transformation through the ethics of care and love (Royster, 2020). Last, we offer the lesson that power exists in communities and, in this case, Black parents. We demonstrate how we can reimagine participatory research in ways that position Black parents as the primary drivers behind research, and the dissemination of that research equips people with solutions that translate into change, change in the education system, and change in spaces where Black learners exist.

To learn more about our results from the Dreams Assessment and the impact of our work, you can access the following documents online:

“Snatch it back like a bad sew-in” is a term used in some communities to reference the ability to take something back quickly from another.

Flexin’ is a shortened version of the term flexing and a Black cultural term used to denote the demonstration of pride.