Although participatory research may include numerous methodological ways for conducting research, one common core philosophical value is inclusivity and engagement in the research (Cargo & Mercer, 2008). Participatory research engages everyone in the research process and includes collaboration with stakeholders, communities, and constituents. The focus is on representation of the individuals with whom the research is being conducted (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020) and is recognized as a critical approach when engaging in research with Indigenous Peoples (Beans et al., 2019; Chilisa, 2019). The strength of participatory research comes from an integration of academic expertise with theory and method, and the knowledge of non-academics that brings in expertise of the context and their own lived experiences (Cargo & Mercer, 2008). In the current project, one early childhood program serving Alaska Native and American Indian (AN/AI) children and families identified a need to more systematically support educators’ reflection on their knowledge, skills, and abilities related to cultural programming in order to improve culturally-responsive teaching within their context. Through an existing relationship with their local university, the identified need from this early childhood community’s perspective was the impetus behind the current project.

This article describes the process of and lessons learned from this participatory community-based research project, which resulted in the co-development of the Guidelines for Culturally-Responsive Reflective Practice in Birth – Five Settings (Harvey et al., 2021), with the most recent version renamed the Culturally Reflective Assessment Tool for Early Educators (CRATEE) (Harvey et al., 2023). In order to understand the project context, we first describe our conceptual framework and operating research paradigm, followed by a brief review of literature on early childhood culturally-responsive practices to provide further rationale for the methodological approach.

Conceptual Framework and Postmodern/Transformative Paradigm

The current research project is situated within the transformative paradigm using a community-based research approach and is guided by Indigenous knowledge and theory, both of which are described below. It is understood that a researcher’s paradigm or “worldview” inherently reflects the researcher’s beliefs and principles in which they operate and interpret meaning (Lather, 1986; Lincoln & Guba, 1985a). From a postmodern/transformative perspective, research is conducted in a collaborative approach while in this case, respecting Indigenous ways of knowing and being (Chilisa, 2019; Creswell & Poth, 2018). Inclusion in the research process extends beyond “the subjects” of research to partners within the research endeavor (Chilisa, 2019; Leavy, 2023), in this research the early learning program and a Cultural Advisory Board (CAB). The transformative paradigm is a human rights and social justice approach to research, in which different theoretical perspectives can be integrated (i.e., critical race theory, feminist theory, Indigenous theory, critical pedagogy, etc) (Leavy, 2023). From this perspective, the research partners are those who have faced discrimination or oppression and who have historically not been an active part of the research process.

Community-based Research

Community-based research, broadly defined, is an approach in which community members engage in the design and implementation of a research project grounded in the shared goal of achieving social justice (Strand et al., 2003). Communities are collective agencies, and community-based research values collaboration, power sharing, and multiplicity or different forms of knowledge (Leavy, 2023). Community-based research methods accept different world views and bring the strengths of these methods together to foster self-empowerment, partnerships, and community change for the better. Research is also approached as a form of education in gaining knowledge for both the researchers, partners, and community (Koster et al., 2012).

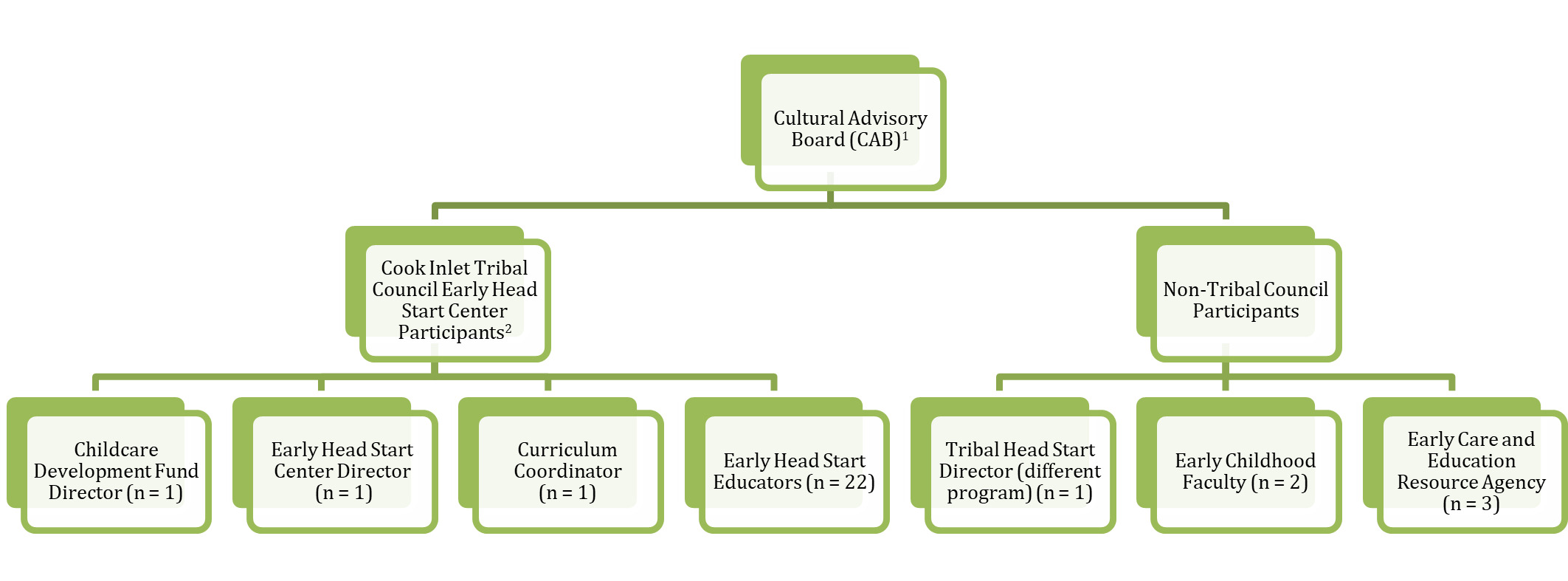

One critical aspect of community-based research is the utilization of a Community Advisory Board (CAB). A CAB helps provide structure for community members and stakeholders to provide input and feedback on university activities, research, and grants to help build capacity between the community and an academic institution (Newman et al., 2011). A CAB in the context of research with Alaska Native/American Indian (AN/AI) peoples serves a critical role to ensure culturally, safe-research practices including processes for recruitment and consent, participation, and data analysis, interpretation, and dissemination (Beans et al., 2019; Leavy, 2023). For this research project, the CAB is referred to as the Cultural Advisory Board.

Collaborative designs within participatory research

As noted earlier, participatory research can be used as an umbrella term for various methodological designs and frameworks, and similarly to community-based research, it includes collaboration with participants. Vaughn and Jacquez (2020) provide a useful tool for determining levels of participation, also known as “participation choice points” (p. 5). As the level of participation in the research process increases, the likelihood of sustainability and social change increases, with collaborative designs reflecting community partners as co-researchers throughout the process. Participatory research approaches with an emphasis on collaborative designs have been utilized in the development of prior assessment tools (e.g., Goldstein et al., 2020) and in prior early childhood assessment research with Indigenous populations (McDonnel, 2016; Peterson, 2017).

Principles of Indigenous Knowledge and Tribal Participatory Research

Indigenous knowledge is grounded in relationships (Peltier, 2018). It is important to foster these relationships by first locating yourself in the research and in every meeting to build connections (Koster et al., 2012). This often includes telling your story and listening to others tell theirs to connect with one another. Western research is often directed in a linear fashion, while Indigenous communities have discussions in a non-linear process (Fisher & Ball, 2003). Acknowledging these differences and the strengths from Western and Indigenous knowledge has also led to the development of Tribal Participatory Research (TPR). TPR is a specific type of participatory research that is situated within the relevant contexts. It works to identify the community’s cultural factors, acknowledge historical trauma and other contextual variables in the community, and embrace community involvement to bring about social change and community empowerment (Beans et al., 2019; Fisher & Ball, 2003). TPR recognizes and addresses the imbalance of power between the researcher and the community. It is critical to recognize Indigenous research methods as a unique process with unique elements aimed to decolonize western methodologies, give voices to Indigenous Peoples, and advocate for research conducted by Indigenous People, for Indigenous People, and with Indigenous People (Chilisa, 2019). While the current research study cannot claim to have conducted Tribal Participatory Research, we attempted to be transparent and reflexive throughout the process and honor the voices and guidance of our collaborators.

Equity and Culturally-Responsive Practices in Early Childhood Education

The framework described above naturally aligns with promoting equity and culturallyresponsive teaching practices, as both honor and respect the diversity of one’s values, heritage, and voice. Culturally-responsive teaching practices recognize the diverse cultures of children and families as strengths, build understanding and respect in children for their own and others’ cultures, and empower children through the cultural values of their family heritage (Gay, 2010). Culturally-responsive environments are those in which home languages and cultures of the children, families, and community are embraced, valued, and are at the core of the curriculum (Kawagley, 2006; National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2019; Paris & Alim, 2017). Early childhood educators are uniquely positioned to advance equity by providing culturally-responsive early learning environments and developing respectful and reciprocal relationships with families. Furthermore, a growing body of evidence points to the necessity for educators to enact cultural humility as a foundation for reciprocity with families and for addressing implicit biases (Harvey & Kinavey Wennerstrom, 2023; Vesely, 2017). This is especially important when working with AN/AI populations, who have historically experienced (and continue to experience) marginalization. Cultural humility can be defined as “a lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique whereby the individual not only learns about another’s culture but starts with an examination of his/her/their own beliefs and cultural identities” (Yeager & Bauer-Wu, 2013, p. 1). This reflective process, coupled with strong family partnerships, can contribute to an increase in culturally-responsive programming in early childhood settings (Ma et al., 2017). Naturally, using a participatory, community-based research approach to partner with an early learning program serving AN/AI children and families supports the call for decolonizing research methodologies (Chilisa, 2019; Lenette, 2022).

Reflexivity Statement

Lenette (2022) reiterated the importance of using reflexivity in participatory research and its crucial role in decolonizing research. Here we acknowledge our engagement in this research as three Caucasian female researchers in higher education, each with a different training background. The first author is of European descent and earned a Master of Science in Child Development and a doctoral degree in School Psychology with a focus in early childhood inclusion and assessment practices. The first author has engaged in extensive professional work, practice, and research in the field of early childhood for the past 20 years. The second author is of European descent and earned a Master of Science in Clinical Psychology with a certificate in children’s mental health. The third author is also of European descent and earned her doctoral degree in Education Policy. The third author has engaged in culturally-responsive educational policy research in Alaska for more than 20 years, with a depth of experience in qualitative research methodologies and in collaborating with Indigenous communities. We acknowledge the presence of our white privilege and power and have attempted to engage in reflection about our positions throughout this process, our relationships with the participating community, and the way we view and interpret meaning. We value non-hierarchical relationships and have tried to respect the knowledge, expertise, and authority of our partners.

Context

This project was situated in a larger project aimed to improve culturally responsive teaching in a local Early Head Start program serving Alaska Native and American Indian (AN/AI) children and families. Early Head Start is a federally funded program designed to provide high-quality early childhood services to children and families from low-income households to support their emotional, social, health, nutritional, and psychological needs. It serves children ages birth through two years and their families. Meanwhile, the federal Head Start program serves children ages three through five and their families (Improving Head Start for School Readiness Act of 2007, 2007).

The larger project was funded by a Child Care and Development Block Grant Implementation Research and Evaluation Grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Research, Planning, and Evaluation. Thus, this work was built upon an existing partnership between the University and a tribal nonprofit organization (hereafter referred to as the tribal council) serving Alaska Native and American Indian people in our region. For context, this tribal council is a partnership of eight federally recognized tribes that acts as a tribal nonprofit organization serving Indigenous peoples across a large region. This tribal council runs a broad array of social services and comprises six divisions, one of which is the Early Head Start center serving children through age three. The early learning center is advised by a Cultural Advisory Board, which served as the community advisory board (CAB) for the current project. As noted earlier, a CAB serves an important role in guiding and providing feedback to the research team and is a recommended practice for participatory, community-based research approaches (Newman et al., 2011).

Cultural Advisory Board (CAB)

The Cultural Advisory Board for the Head Start center is comprised of 13 members, 11 of whom are Indigenous. CAB members participated in the initial conceptualization of the project and provided guidance throughout the project. These contributed to the reliability process by serving as member checks, providing accountability for the project’s progress, and ensuring culturally safe research practices (Brockie et al., 2022). The CAB was also critical for brainstorming adjustments during COVID-19 when researchers were no longer able to conduct classroom observations as part of the inter-rater reliability process and provided input into the focus group questions.

Research Purpose and Question

The primary purpose of this smaller project was to co-identify and develop a process to help early childhood educators utilize and be guided by culturally-informed practices and reflection in their early learning environments in both their interactions with children and families, and in their program planning with a specific focus on the Alaska context. Reflecting on and evaluating the relationship between the researchers and the community partners throughout the process was essential and is described as part of the lessons learned. The primary research question that was developed as part of the participatory process was: What is, and how do we measure, culturally-responsive practice in an Alaskan & Indigenous early education context?

Methods

Design

This research process utilized key principles of community-based participatory research and followed a multiphase, responsive design approach (Pohl & Hadorn, 2007), an interactive process in which different phases are revisited, revised, and adapted based on new ideas or perspectives (Leavy, 2023). This comprehensive and collaborative process involved many voices and sources of information, expertise, and guidance as is aligned with participatory research and responsive designs (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Jason & Glenwick, 2016; Leavy, 2023). The key questions are developed along the way rather than identified by the researchers ahead of time, as is common in a responsive design (Pohl & Hadorn, 2007).

Participants

Given the research approach using a multiphase, responsive design, numerous individuals were involved in the project throughout its two-year duration. A total of 30 participants intersected with different phases of the project. Participants included the tribal council Child Care Development Fund director (n = 1), the Early Head Start program director and curriculum coordinator (n = 2), and the Early Head Start classroom-based educators (n = 22). Non-tribal council community members who participated in the process included members of the state’s Early Care and Education Resource and Referral (R&R) agency (n = 3), a Tribal Head Start Director from a different program who had been in the position for 13 years (n = 1), and higher education early childhood educators (n = 2) who were included as part of the content expert review process (see Figure 1 for a graphic organizer of participants). Participants’ ages ranged from 18–68 years old. The participants from the Early Head Start (n = 24) represented a broad range of self-reported race identities including Alaska Native (n = 13), Russian (n = 1), Pacific Islander (n = 3), Hispanic (n = 2), Black/African American (n=1), and white (n=4).

Procedure

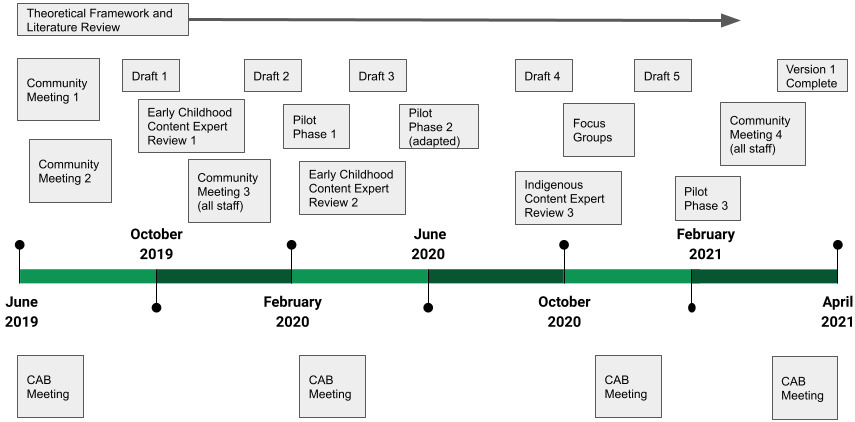

After obtaining approval from the researcher’s Institutional Review Board, a series of community meetings, content expert reviews, cultural advisory board meetings, focus groups, and pilot testing occurred from June 2019 through April 2021 (see Figure 2 for timeline).

This followed the principles of recursiveness, an interactive process where the team continuously revised the draft tool, repeated steps, checked for agreement, and adapted to new ideas or perspectives (Leavy, 2023; Pohl & Hadorn, 2007). Figure 3 outlines the recursive process employed in this study using broad references to each step of the process and the role of community members. The components of this recursive process are described below.

Community Meetings

Four community meetings were held over the course of the project, each which served a different purpose in the research process, including assessment tool development and data analysis and review. The first community meeting defined the project purpose, identified project goals, and developed a timeline. Participants included the Early Head Start program director and curriculum coordinator, the tribal council Child Care Development Fund director, a member of the state early childhood resource and referral agency, and two of the researchers. The second community meeting was held to brainstorm, draft, and conceptualize the early childhood assessment tool with the guiding question, what do we want to measure? This included a review of an existing state cultural assessment tool for K–12 and resulted in Draft 1 of the tool. Participants included the Early Head Start curriculum coordinator, two members of the state early childhood resource and referral agency, and prior author of the K-12 tool that was being reviewed, and two of the researchers. The third meeting introduced the draft assessment tool to all the classroom-based educators and engaged in open discussion and feedback from the Early Head Start educators and staff (n = 24). This was a critical step given the expertise of early childhood educators who brought perspective about the direct application and use of this assessment tool in the classroom context. This meeting was conducted as part of a staff development day focused on culturally responsive teaching and learning. The fourth community meeting occurred near the end of the project (April 2021) in which the final version of the tool was shared with the Early Head Start community, also occurring on a staff development day. The last community meeting also served as part of the validation process in obtaining member checks to determine if the final version reflected the educator’s prior feedback.

Content Expert Reviews

Using DeVellis’ (2017) scale development guidelines, two content expert reviews occurred following the development of Drafts 1 and 3 of the tool. The content review experts included the early childhood education faculty members and two members of the state’s early care and education agency. The content experts were asked to review two different drafts of the assessment tool and respond to the following questions: 1) Is the description of the tool clear and understandable?; 2) Are there any terms, concepts, or language used that an early childhood educator may not already understand?; 3) Does the sequence of the indicators across the standards follow an expected developmental sequence?; 4) Are there additional examples you would add to the indicators?; and 5) For each standard (the language was later changed to component) is there any language you would suggest changing? An open-ended question was added at the end to allow additional feedback from reviewers. A third content expert review was conducted with three Alaska Native educators from Early Head Start in order to examine the language and cultural examples from the educator’s perspectives. The same questions outlined above were used to guide the review.

Pilot Testing

Two planned phases of pilot testing with the assessment tool were planned with the initial goals of testing tool usability and obtaining inter-rater agreement (DeVellis, 2017). A revision of the tool occurred between each pilot phase (see Figure 2). This paper provides an overview of the pilot testing as part of the participatory research process.

Phase 1 pilot testing included the following procedures: 1) Three early childhood education observers observed seven teachers during a 45–60 minute period, followed by a 5–10 minute interview asking five follow-up questions as part of the assessment protocol; 2) Each observer independently rated each teacher on the four-point scale indicators within the three primary components, for a total of six ratings per teacher using the classroom-based observation data and the teacher interview responses; and 3) inter-observer agreement was calculated. For Phase 1 pilot testing, inter-observer agreement across the seven teacher ratings was 87.85%.

In response to COVID-19, Phase 2 of the pilot testing was adapted based on discussions with the researchers, CAB, and the Early Head Start administrators. Following the submission of a revised IRB approval, the assessment tool was input into an online survey using Qualtrics. Educators (n = 22) completed a self-assessment along with two of their supervisors who also completed an assessment for each educator. These assessments were completed twice: one before and once after training on how to use the tool. Inter-rater agreement for pre-training was calculated for each educator and the two supervisors, with agreement ranges from 0-100% and an average of 31%. Inter-rater agreement for post-training ranged from 0-100% and an average of 73%. All training was completed via Zoom.

Phase 3 pilot testing was an additional adaptation to COVID-19 and consisted of a random selection of six educators (from the original 22) who recorded a one-hour video of themselves in the classroom wearing a swivel camera, followed by a Zoom interview with two of the trained observers. Similar procedures were followed as described in Phase 1, and two observers independently scored each teacher using the recorded classroom videos and the teacher interview responses. For Phase 3 pilot testing, inter-rater agreement across the six teacher ratings was 93.25%.

Focus Groups

Following the pilot testing Phases 1 and 2, all educators were invited to participate in a follow-up focus group. Invitations were sent via email along with verbal invitations from supervisors who had the relevant contact information. The focus groups obtained feedback from the educators on the usability and applicability of the assessment tool. Two focus groups were conducted using HIPPA-compliant Zoom meetings (occurred during the pandemic) and were composed of five and six educators, respectively. The two lead researchers facilitated the focus groups, which lasted approximately one hour, and the researcher assistant observed. Prior to beginning the focus group discussions, participants were read a verbal-informed consent and provided with an opportunity to ask questions. Participants were provided a $30 gift card by the tribal council as a thank you for their time.

The focus group consisted of seven semi-structured interview questions (i.e., what are your thoughts and feedback on components A, B, and C?; do the indicators make sense to you as a classroom educator?). Questions were derived from content expert reviewers and the researchers as they reflected on the pilot testing and were reviewed by the CAB. This reiterates the involvement of multiple participants at multiple times throughout the process, a key aspect of participatory research. The semi-structured format allowed all respondents to answer the same questions and increased the comparability of responses. This format also helped to reduce interviewer bias by having more than one facilitator present to conduct the focus groups.

Focus group data analysis

Focus groups were not recorded, thus transcripts were not used for data analysis. The three researchers made field notes during this phase of data collection (Charmaz, 2000; Patton, 2002). Research team members each noted salient responses to the interview questions by participants and made notes to form ideas relating to potential themes for guiding the assessment tool revision. The researchers met multiple times over Zoom to discuss notes, parse out potential themes, discuss quotations supporting primary ideas, and then synthesize them into key areas for improving the tool. The research team used interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) to capture and interpret the educator’s experience with the assessment tool and to assist in understanding how the educators might use this in their educational setting to inform culturally responsive practices (Smith et al., 2009). Major themes and points were shared with the participants at the end of each focus group as part of the member checking process (Lincoln & Guba, 1985b). This led to identifying areas of consensus for tool improvement as well as specific recommendations to reflect appropriate cultural language, which are discussed below in the findings and reflections section.

Establishing Trustworthiness of Data

To ensure the research was conducted with rigor, efforts were made to ensure trustworthiness of data as outlined by Lincoln and Guba (1985b). This included triangulation of the data by relying on multiple sources (i.e., community meetings, content expert reviews, pilot study, and focus groups) to support conclusions and three different investigators who reviewed all stages of the data collection process. To address confirmability, all efforts were made to clearly articulate the research procedures. To ensure credibility, we engaged in member checking at multiple stages of the process, including use of the CAB, summarizing major points at the end of the focus groups, and sharing drafts of the tool with educators. To promote transferability, we have attempted to share sufficient detail about the research process and the contexts in which the research occurred.

Findings and Reflections

This research study was framed using a participatory, community-based research approach with a recursive, responsive design. Through the research process, the community participants identified the need to develop an assessment tool that could help early childhood educators and programs reflect on and improve their culturally informed practices in their early learning environments and interactions with children and families with a specific focus on the Alaska context. Using guidance from Vaughn and Jacquez (2020) participation choice points, the aim of this research was a collaboration in which there was shared decision-making and feedback throughout the research process.

Here we describe the primary project outcome followed by a reflection on the process of using a participatory, community-based approach. These reflections are intended to highlight key components of the participatory approach situated within the transformative theoretical paradigm in which participants were empowered to guide and shape the outcomes of their project.

Primary Project Outcome: Assessment Tool Development

One primary outcome of this research process was the development of the Guidelines for Culturally-Responsive Reflective Practice in Birth – Five Settings (Harvey et al., 2021), with the most recent version renamed the Culturally Reflective Assessment Tool for Early Educators (CRATEE) (Harvey et al., 2023). As guided by the participants, this assessment tool was created to be utilized and adapted across cultural contexts and regions and notes that educators are encouraged to utilize examples from their own cultural experiences. The assessment tool includes a purpose statement that reflects the collective voices of participants:

The primary purpose of this assessment tool is to guide self-reflection of culturally responsive practices in order to identify areas of strengths and areas for continuous improvement. It is designed to complement other existing standards and competency guides within Alaska’s early education system. (Harvey et al., 2021, p. 4)

Furthermore, the document reflects a deep appreciation and integrated focus on early childhood development and Alaska Native practices:

The practices in this guide are built on essential foundational practices for working with infants, toddlers, and preschoolers and their families that must be present and supported within the early education setting. These include relationship-based practices and a primary focus on child and family engagement. (NAEYC, 2019)

This document guides reflection specific to culturally-responsive practices, in which relationship-based, responsive caregiving is essential and aligns with Alaska Native traditional knowledge and systems.

The CRATEE is organized around three primary components (see Figure 4), each of which is composed of specific measurable indicators on a four-point scale (ranging from not yet observed or emerging to exemplary). The guidelines emphasize that the exemplary category is not an end-point that is purely mastered, but rather recognizes the continuous, lifelong reflection and learning that can occur over time — a direct result of consensus across stages of the research process. Although not a full description of the assessment tool is provided here, we highlight this outcome as part of the transformative paradigm used to answer the guiding research question, What is, and how do we measure, culturally-responsive practice in an Alaskan & Indigenous early care and learning context?

Lessons Learned from Pilot Study and Focus Groups

As part of the assessment tool development outcome, it is critical to honor and recognize the voices of key members of the project who contributed to this outcome. Educators had multiple contributions both as part of the pilot study and the focus groups. From the pilot study, educators reflected in written feedback with specific suggestions for improving the representation of a variety of regions in Alaska by using broad statements that would be inclusive of regional diversity (e.g., Educator learns about cultural values, local culture(s) and traditional knowledge systems by attending local cultural events and activities (i.e., berry picking, dances, family story-telling, attending a cultural storytelling event at the local library, cooking, etc.)). Several educators provided comments about expanding their personal understanding of diverse cultural parenting practices. Thus, language was used in the tool to demonstrate developing skills such as, “Educator begins to identify one’s own family values” (e.g., feeding and mealtime practices, beliefs on co-sleeping, encouraging independence, social or religious beliefs) and shares with a colleague or program administrator, to exemplary skills such as, “Educator researches, reads, and has conversations about other cultural parental beliefs and practices” (Harvey et al., 2021, p. 14).

The interactions during the focus groups highlighted a key component of participatory research: shared power and diverse sources of knowledge (Brockie et al., 2022). Educators contributed to changes in the assessment tool (e.g., adding self-reflection of cultural biases and perspectives as a foundation to application; ensuring inclusion of families as part of the relationship-building process; specifying cultural examples) and to ways in which to utilize the tool. A collective agreement was shared during one of the focus groups in which the educators discussed how not all components of the tool would work for every classroom or situation. This resulted in specific language on suggested usage as an assessment tool for program improvement versus mandatory high-stakes decision-making on teacher performance. Educators also brought the need to make sure the process was collaborative with and representative of Alaska Native peoples from all areas of Alaska if the assessment tool was to be used statewide to the researchers’ attention. This connected to the educator’s written feedback, resulting in language changes to ensure representation of diverse geographical regions. As another example of this shift to inclusive language, “Educators are aware of seasonal harvesting and gathering in cultural regions reflective of the children and families in their classrooms and program,” and “Educator describes multiple regions and cultural values and links to curriculum planning” (Harvey et al., 2021, p. 15). In Alaska, there are five major cultural regions, 229 federally recognized Alaska Native tribes, and over a 100 dialects with sub-dialects.

These examples from the educator participants exemplified a key component of our theoretical framework, the postmodern/transformative paradigm in which the narrative was focused on the voices of the participants, shifting the discourse of power in which the participants answered their own questions about how to measure and improve culturally responsive practices in their early childhood setting.

Reflections on the Research Process

Two primary reflections on the research process are discussed. First, research adjustments made during COVID-19 and its impact on the participatory approach; and second, lessons learned through reflexivity.

Reflections on Adjustments During COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic occurred after Phase 1 of the pilot study and continued through Phases 2 and 3. The benefit of using the participatory approach meant that we were able to gather input and guidance from the CAB to ensure we retained using culturally safe research practices including considerations on the impact of the research changes on a population which was identified to have a higher social vulnerability to COVID-19 (Hathaway, 2021). In addition, a benefit of using participatory research is that it allows for flexibility and innovation in a problem-centered capacity, as things do not always go as planned (Leavy, 2011). We had to revise our human subjects’ approval to reflect changes from in-person observations to online self-assessments, and later added video recordings with swivel cameras when in-person classes returned but outside guests were not allowed in the classrooms. As Leavy (2011) describes, this flexibility and innovation must occur with a clear delineation of roles and responsibilities to ensure the new changes align with the community partner’s goals and maintain community protection (Beans et al., 2019).

One downside to this adaptation was that there was a significant time gap between the educators using the self-assessment tool and engaging in the focus groups. Having the focus groups sooner after the teachers completed the self-assessment tool would have been beneficial. However, despite the time gap in reflection with the CAB, the research team members, and the participants, these adaptations from our original research plan due to COVID-19 actually resulted in strengthening the process and outcomes. Here, the educators and their supervisors had a new opportunity to engage in self-assessment and reflection in a different way than was originally planned. In addition, by videotaping in the classroom with a swivel camera, the teachers were able to watch their own teaching and engage in conversation with the research observers. These changes reflect the responsiveness of the participatory research design and further empowered participant voices. One educator wrote in her reflection,

I have knowledge of the Yup’ik tradition and Cultural Values. I grew up with my grandparents, my parents, and the community elder teachings as well as mentors… I share and apply my learnings to my children and grandchildren as well as with other children. I speak my language fully, read it, and write it. I want to share this knowledge with others and I can use this [tool] in my work with other educators. (educator participant, 4/29/2020)

Lessons Learned Using Reflexivity

During this research, it was important for us to continue to reflect upon our own paradigms within the research and community to identify context, values, and beliefs while engaging in research to provide trustworthiness, authenticity, and confirmability to the study (Creswell & Poth, 2018). We also learned the importance of vulnerability, acknowledging that as researchers we are not always the ones who know, as this would perpetuate the Western perspective that the researcher is the leader or the decision maker. Following one of the focus group sessions, one researcher wrote in her reflection journal:

As I engage with cross-cultural research through my lens as a white female, trained in Western methodological approaches yet cognizant of the vast meanings to ethical, responsible and responsive engagement with Othered cultures and populations, I am faced with and challenged by my own biases, beliefs and ideas. I want to think I’m doing the process right, that I have included who needs to be included, but how do I know? And even as I have attempted to include others and have asked the community who should be here, this feels biased, in that I am somehow in the position of authority, the researcher, the one leading the process who is doing the asking.

Later, this same researcher reflected after an Indigenous community member during a focus group stated to her that she was not Indigenous and should not be leading this research. She wrote, “This is hard work, I’m not sure I want to do this, and I’m not sure I’m comfortable with it. I’m trying to partner, to value and honor voices, yet I feel like I don’t belong and that I’m being criticized for trying to be an ally.” Here, recognizing feelings of being uncomfortable led to greater empathy and understanding, particularly as it linked to the historical trauma experienced by Western methodologies with Alaska Native peoples. This comment may have been reflective of a greater advocacy effort to increase Indigenous research by Indigenous researchers, which is honorable. In contrast, another focus group member, who was of Indigenous heritage and a well-known community leader commented to the researchers, “[you are]… honoring the voices and heritage of the community by engaging in this inclusive practice and by giving power to our voices” (focus group member, 10/11/19).

Not having a researcher who was of Indigenous heritage was a weakness of the research, as may be reflected in the above comments. However, we attempted to be transparent and seek out counsel from Elders and Indigenous members of the CAB. We also took time to reflect upon how we impacted the research and grounded ourselves in Indigenous knowledge, focusing on fostering relationships (Peltier, 2018). It is important to foster these relationships by first locating yourself in the research and in every meeting to build connections (Koster et al., 2012). This often includes taking time to tell your story and listening to others telling theirs. The researchers did this by building connections during focus groups and meeting with individuals more than once, sometimes just for coffee or informal conversations. Two of the researchers spent time in the early childhood classrooms with the teachers and children, not as part of data collection, but as part of the relationship-building process. This was critical to ensuring we engaged in continuous reflexivity.

Conclusion

Using a participatory, community-based research approach in this project allowed for greater connection and collaboration with our research partners, in which their voices guided the project outcomes while honoring different forms of knowledge. The value and core belief of the Indigenous ways of knowledge framework (Peltier, 2018) is doing research with and not on individuals (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020). This is an important aspect of any participatory research, and in particular conducting research with Alaska Native and American Indian individuals, organizations, and tribes given the past negative impacts of research and the collective historical traumas experienced. Protection must be taken to build trust and repair relationships (Beans et al., 2019). All aspects of the research need to be strength-based, and not focused on deficit paradigms. When creating new educational programs or forms of assessment they need to promote healing and self-efficacy and be grounded in cultural belief systems (Caldwell et al., 2005). Here, we recognize the critical role that the educators and early childhood administrators played throughout the development of this assessment tool, re-emphasizing the value added when the participants are the community individuals for whom the research directly impacts.

The outcome of this project has indeed positively impacted participants and has led to broader statewide implications in which this assessment tool is now integrated into the state’s early learning Quality Rating and Improvement System. Future researchers may consider how using participatory community-based research can enable and empower communities to address priorities and create and promote social change.