Introduction

Violence against women and girls is a shared reality across the globe, with men being primarily responsible for physical and sexual violence within and outside intimate partnerships (Amnesty International, 2015; World Health Organization, 2021). This reality is reflected in the four regions focused on in this study, Canada, the Caribbean, Nepal, and Pakistan, where we initiated a community of practice on men’s gender justice work. In Canada, women experience almost 80% of police-reported interpersonal violence (IPV) and are 4.5 times more likely than men to be victims of spousal homicide (Burczycka, 2016). In the Caribbean, 46% of women had endured at least one form of intimate partner violence in their lifetimes (UN Women, 2020). Studies in Nepal have estimated that 22% to 48% of Nepalese women have experienced IPV (Government of Nepal, 2012; Ministry of Health, Nepal et al., 2017), although experiences of IPV are vastly underreported and assumed to be higher than indicated (Baral et al., 2016). In Pakistan, violence against women and girls remains a serious public health and complex social problem (Naqvi et al., 2018), with approximately one in four women reporting emotional abuse (26%) and physical violence (23%) (Imran & Yasmeen, 2020).

Women and other violence prevention advocates have long highlighted men’s disengagement from violence prevention initiatives and overall resistance from patriarchal systems of government and society (Flood, 2011; Minerson et al., 2011; Schmitz & Kazyak, 2016). Concurrently, organized “men’s rights” movements have been effective at gathering men in self-advocacy roles to further maintain and extend patriarchal norms and legislation (DeShong & Haynes, 2016; Hodge & Hallgrimsdottir, 2019). Proponents of these often well-funded coalitions have been adept at employing social, political, and economic power to influence policies and practices under the guise that IPV in heterosexual relationships is bi-directional, and that responses to gender-based violence (GBV) are biased and gynocentric (Joseph-Edwards & Wallace, 2021).

Men are primarily responsible for physical and sexual violence within and outside intimate partnerships (Amnesty International, 2015; World Health Organization, 2021), despite an increasingly vocal contingent of men who do not condone GBV (MenEngage, 2022). While numerous barriers to involving men in transforming inequitable social relations persist, there has been a notable increase across the globe in men’s organizing efforts to end GBV and promote gender justice over the last three decades (Lorenzetti & Walsh, 2020; Barker & Ricardo, 2007). This has been characterized as a shift from a sole focus on intervention work with perpetrators of violence to awareness and educational programs, disseminated through community organizations, social media, and political campaigns targeting men and boys (Claussen, 2020; Flood, 2011). A global survey of this work indicated several strategies being employed, including resourcing, training, and engagement work with men (Carlson et al., 2015; Haynes, 2018; Reddock, 2004). To further men’s gender justice engagement on a global scale, interdisciplinary, local, regional, and cross-regional efforts are required. However, there is a limited understanding of how cross-regional collaborations account for intersectionality, geo-political differences among stakeholders, and the value of local strategies when designing and sharing prevention frameworks.

Catalyzed by emerging and long-standing gender equity movements, our interdisciplinary research team from Canada, the Caribbean, Nepal, and Pakistan employed a community of practice (CoP) framework to share and mobilize research and experiential knowledge with the purpose of promoting regional and cross-regional strategies to involve men in gender justice efforts. Our growing team of 22 international activist scholars, students, and organizational leaders from five academic institutions and four community organizations coalesced around shared commitments to gender justice and common interests in our existing and emerging research, education, and activism in GBV prevention and gender equity. Our disciplinary and interdisciplinary roles in social work, international development, political sociology, and diverse ethnocultural and linguistic backgrounds contributed to the development of a shared agenda for collaborative work (See Appendix A for team member regions and interests).

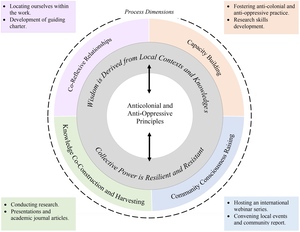

This article outlines the International Community of Practice (CoP) framework that we mobilized to advance collaborative learning, interdisciplinary knowledge sharing, transnational research, and community outreach related to men’s roles in violence prevention. We share the anticolonial and anti-oppressive principles developed by the Alberta Men’s Network, one of our partner organizations in Canada, that forefronted our collective process. We then elaborate on the co-created position statements, process dimensions, and key CoP activities that root our international collaboration and guided the team’s collective goals of fostering anti-colonial and anti-oppressive practices within our collaboration. We emphasize the unique local contexts for our work and the learnings that emerged from our CoP. Lastly, we reflect on the opportunities and challenges of the proposed framework and how it may be used to advance collective and interdisciplinary agendas across global contexts and further the work of groups committed to transformative social change.

To authenticate the knowledge shared in this article, we locate ourselves (Carter & Little, 2007). Our author team includes a Canadian-born anti-racist, feminist scholar and social work organizer of Italian heritage; a Pashtun Pakistani-born Canadian activist scholar, advocate, and researcher for men’s engagement in gender justice and girls education; a Nepali-born Canadian activist scholar, community organizer, and researcher in anti-trafficking and HIV with more than 20 years of experience in the field; an Indo-Caribbean Trinidad and Tobago feminist scholar with more than 25 years of experience in research, education, and activism in Caribbean feminisms, gender-based violence, and men’s movement-building; a Canadian-born feminist and anti-racist community social worker and emerging activist scholar from Dutch, Welsh, English, and Scottish heritage; and a Canadian-born anti-racist, pro-feminist social worker and activist scholar from Norwegian, German, and Scottish heritage.

Literature Review and Context

As a complex and intersectional social issue, GBV prevention necessitates involvement and leadership from interdisciplinary and diversely skilled local and cross-regional teams. Participation in interdisciplinary teams enables academics, organizations, and community collaborators to move beyond socio-cultural, disciplinary, national, and geographic silos to better explore and address pervasive and multifaceted issues (Trussell et al., 2017; Vestal & Mesmer-Magnus, 2020). Interdisciplinarity fosters creativity and practicality in attending to pressing social issues by effectively mobilizing research, knowledge, education, and theory (CohenMiller & Pate, 2019; Nissani, 1997). Successful interdisciplinary teams build on individual and group motivations, create opportunities for the sharing of skills and strengths brought forward by team members, promote opportunities for individual and team growth, and resolve emerging challenges through active and consistent communications (Lorenzetti et al., 2022; Tkachenko & Ardichvili, 2020; Vestal & Mesmer-Magnus, 2020). While interdisciplinary teams bring together diverse knowledges and expertise to enrich a team’s capacity to produce research and inform practice, a CoP moves beyond disciplinary boundary-crossing and interdisciplinary contributions toward common learning goals. In this way, a CoP prioritizes a collective learning process rooted in relationships of mutual benefit to influence transformative change and solidarity action that interlinks research, practice, and social change (Poole & Bopp, 2015).

Communities of Practice

A Community of Practice (CoP), a concept first proposed by Lave and Wenger (1991) through their study of social learning theory, is a formal model or system that fosters a “community that acts as a living curriculum” (Wenger-Trayner & Wenger-Trayner, 2015, para. 13). CoPs were initially conceptualized as collaborative spaces for exchanging and co-creating professional and personal knowledge with the purpose of enhancing practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998, 2010), and are commonly employed across various sectors. Wenger and colleagues (2002) identified Seven Principles for Cultivating Communities of Practice: 1) Design for evolution; 2) Open a dialogue between inside and outside perspectives; 3) Invite different levels of participation; 4) Develop both public and private community spaces; 5) Focus on value; 6) Combine familiarity and excitement; and 7) Create a rhythm for the community. Building on the original principles, Wegner-Traynor and Wegner-Traynor (2015) later named three specific domains by which CoPs could be identified: including the presence of common interests or objectives; relationships of mutual engagement; and sharing knowledge, resources, and skills.

While the theoretical grounding and application of CoPs continue to evolve from earlier conceptualizations (see Wegner, 1999), CoPs are comparable to interdisciplinary teams as both can be long-standing or responsive, and function in physical or virtual spaces (Wenger, 1998, 2010) to enhance critical thinking and leverage skills (Barwick et al., 2015). CoPs expand on the purpose of interdisciplinarity by encouraging their members to develop dynamic relationships through various means of interacting across interdisciplinary teams and communities while centering the focus issues within lived experiences and local knowledge (Barwick et al., 2015). These interactions equip CoPs with the ability to process discussions and strategies that reflect the connections and tensions between practice knowledge, experiential knowledge, and local cultural knowledge within regional and cultural contexts (Barwick et al., 2015). Siegelbalm (2022) provides an experiential reflection on successful CoPs, viewing them as a method of “connecting local pockets of expertise… [and] communal resources that evolve over time” (para. 11). She further contended that CoPs are rooted in the commitment of members whose participation and strategic objectives are derived from hands-on, community-centered, and culturally situated knowledge, as well as empirical and institutional ways of knowing.

A review of the literature uncovered only a few CoP practice models and limited evaluations of their effectiveness. Gullick and West (2016) evaluated the impact of the Seven CoP Principles (Wenger et al., 2002) on capacity building and research productivity among nursing scholars. Participants (n=25) indicated that the CoP was primarily successful in that it “invited differing levels of participation, allowed for evolution of the research community, and created a rhythm of research-related interactions and enduring research relationships” (Gullick & West, 2016, p. 605). Barwick and colleagues (2015), through their collaborations for cancer and chronic disease prevention, developed a 14-step guide for building and utilizing a community of practice. Key identified strategies include: establishing a charter and working structure; developing a skills and knowledge inventory; developing, identifying, and updating relevant content; engaging the community; and evaluating effectiveness. The authors did not engage participants in evaluating this approach (Barwick et al., 2015).

Centering Intersectionality within a CoP Process

While the focus on participation and co-learning through the sharing of knowledge, skills, and resources are defining features of most CoPs, absent in CoP frameworks is attention to power dynamics, culture, and intersectionality. A notable exception was a CoP model developed by researchers and community-based advocates in northern Canada that focused on increasing culturally safe and supportive services for women and children experiencing homelessness (Poole & Bopp, 2015). The initiative, Repairing Holes in the Net, proposed a six-step cyclical model to facilitate change based on “experiential wisdom, practice wisdom, policy wisdom, research evidence, and traditional Indigenous ways of knowing” (Poole & Bopp, 2015, p. 127). The model engaged members in an experiential process designed to purposefully counter normative and structural power hierarchies through practices to “reaffirm common purpose, share knowledge and expertise, learn from the knowledge and experience of others, reflect together about what this means for our practice, consult about the small steps we could take individually and collectively, plan for the next learning goals” (p. 130). The participating group reflected that endorsing a CoP framework catalyzed co-learning, knowledge, and skill sharing between virtual networks as a key strategy for influencing and enacting relational system change (Poole & Bopp, 2015). Another study, by Hakkola and colleagues (2020), examined the outcomes of a CoP in a northeastern university in the United States that was committed to increasing equity. Participants shared that the CoP helped many to name and reflect on inequities, share resources, and provided a safe and like-minded community to examine their own practices.

Reflecting on the CoP literature in relation to men’s roles in gender justice and violence prevention, a CoP process must attend to the socially constructed root causes of violence: patriarchy, colonization, racism, class, and intergenerational trauma (Carbado & Harris, 2019). At the same time, within a global context, intersectional practices within an effective CoP must account for and prioritize culture, faith, and geopolitics within local prevention efforts (Jamal, 2018; MenEngage, 2022), while also exchanging knowledge, strategies, and building relationships across regional and national boundaries to support and catalyze change.

Responding to an increasingly urgent global call for men’s engagement in the prevention of GBV and the promotion of gender justice, our global team took up this challenge through a participatory and engaged pedagogical process (hooks, 1988) of developing and documenting an emerging CoP framework for cross-regional praxis on men’s gender justice work. Building on our experiences, learnings, and co-reflexive practices from Canada, the Caribbean, Nepal, and Pakistan, this article shares our proposed framework and how it may be used to advance collective and interdisciplinary violence prevention agendas across global contexts and further the work of groups committed to transformative social change.

Designing an International CoP Framework

The design and implementation of our International Community of Practice Framework for men’s gender justice engagement emerged from a growing call to advance a social justice response to gender inequity and GBV within and across our contexts and regions. Our framework was developed through a participatory process that was rooted in anticolonial and anti-racist principles first developed by one of the partner organizations, the Alberta Men’s Network. We drew on the strength and diversity of our cross-regional team in view of establishing and maintaining a virtual ethical and relational space in order to elevate the sharing and implementation of knowledge exchanges and mobilization plans. We employed power-sharing strategies and respect for local contexts and leaders, which established a cyclical process of co-reflexive (Gergen, 1999; Gilbert & Sliep, 2009) relationship-building, capacity-building opportunities, community-consciousness-raising activities, and knowledge co-construction and harvesting (Brown & Isaacs, 2005; Freire, 1970). From this process, we implemented numerous collective actions and local activities over a two-year period. The underpinnings of the framework are discussed below and are visually represented in Figure 1.

Integrating Anticolonial and Anti-Oppressive Principles-In-Action

During the beginning stages of forming our team, we adapted AMN’s anticolonial and anti-oppressive guiding principles (Lorenzetti et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020), with the intention of ethically rooting our collective virtual space. The four principles-in-action incorporated within our CoP were: 1) safety through relational accountability; 2) intersectionality; 3) belief in diverse and collective expertise; and 4) working towards an anti-oppressive environment. Drawing on Ermine’s (2007) conceptualization of ethical space, these principles were actioned with the purpose of encouraging CoP members to prioritize good relations and mutual respect over the tasks and outcomes typically associated with research partnerships.

The first principle, safety through relational accountability, centers on the concept of cultural safety (First Nations Health Authority, n.d.), a sense of belonging, and investment in relationships of respect, reciprocity, and accountability towards one another (Lorenzetti et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). Confidentiality is included within this principle as a reminder that discussions should be safeguarded and kept within the group (Wang et al., 2020). Specifically, Indigenous principles of reciprocity (Wilson, 2008) underpinned our collaboration. We further drew on the practices established by the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC), which underscore the importance of ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP®) of people and communities for the knowledge and outcomes of a research undertaking (FNIGC, 2022). OCAP® was viewed by team members as an essential disruption to oppressive power dynamics often present in partnerships between so-called Global North and South collaborators. Researchers from the Global North maintain unbalanced access to resources to both conduct and publish research due to socio-economic privileges and the concentration of privileged knowledge within Northern academic contexts (Fals Borda, 2001).

Intersectionality, the second principle, is a complex and multi-layered approach to understanding how various types of oppression create an additive and unique confluence of disadvantage for certain people or communities within societies (Crenshaw, 1989, 2017; Weldon, 2016). Hankivsky and Cormier (2011) contended that intersectionality involves “taking into account that social identities such as race, class, gender, ability, geography, and age interact to form unique meanings and complex experiences within and between groups in society” (p. 217). It is our understanding that through an intersectional lens, the complexities of violence, oppression, and inequities that exist in every community can be more thoroughly understood and resisted (Lorenzetti et al., 2018). Beyond analyzing our individual contexts, we were encouraged to see each other through an intersectional lens and respect the unique experiences and perspectives of each CoP member (Wang et al., 2020).

The need to respect all forms of knowledge is articulated through our third principle, belief in diverse and collective expertise. Through our participatory CoP practices, we strove to embody this principle by understanding and amplifying knowledge and expertise that not only resides in individuals with positions of influence and power, but also among community members and local groups. We aspired to create a space for equitable sharing and mutual learning for knowledge exchange (Wang et al., 2020).

The fourth adopted principle, working towards an anti-oppressive environment, responds to our awareness of intersectional oppression (principle 2) that is persistent in various forms throughout our local and global contexts. Anti-oppressive practice (AOP) is the work to address the consequences of oppression experienced by individuals while concurrently working to undermine those structures of oppression (Baines, 2010; Dominelli, 2002). As team members committed to personal and social transformation, we endeavored to acknowledge that inequities, privilege, and power differentials exist among individuals and communities; we were also critically reflexive while encouraging and providing space for individuals and community voices that experience sexism, racism, and oppression in all forms (Wang et al., 2020). This was done through relationship-building and check-ins in smaller groups and regional meetings, as well as assuring that each large-group gathering included time for dialogue, critical questions and the sharing of unique and collective experiences, barriers, and proposed shifts in the workplan that would better fit with team members. Our team used AOP to analyze our local and global socio-political contexts and inform our ethical commitments to political action (Brown, 2019).

Epistemological Position Statements

Derived from our four principles-in-action were two core epistemological position statements that guided the implementation of our CoP framework. The first statement, wisdom is derived from local contexts and knowledge, was a reminder that knowledge cannot be uncoupled from lived experiences and that knowledge and wisdom are rooted in belief systems that are valuable and integral components of social transformation.

Our second epistemic statement is collective power is resilient and resistant. Rooted in our collective work and evolving awareness of oppression as both personal and systemic, we viewed collective power as increasing our capacity to break through imposed isolations and divisions to accrue the necessary insights and strengths for solidarity-building. As a contrast to hierarchical power, collective power is the embodiment of mutual aid, which, as suggested by Spade (2020), fosters community care and mobilization among society as “people learn and practice the skills and capacities we need to live, in the world we are trying to create” (p. 138).

CoP Process Dimensions and Activities

Grounded in our ethical principles and informed by our epistemological positions, we established four process dimensions within which our participatory activities would take place. These included co-reflexive relationships, capacity building, community-consciousness raising, and knowledge co-construction and harvesting. These concepts are defined below in the context of our collaboration, with examples of the activities that were established and implemented within each dimension.

Co-Reflexive Relationships

Gergen (1999) defined reflexivity as “the attempt to place one’s premises into question, to suspend the ‘obvious,’ to listen to alternative framings of reality, and to grapple with the comparative outcomes of multiple standpoints” (p. 50). Gilbert and Sliep (2009) expanded on this notion, proposing reflexivity as a collective process where assumptions and intentions can be critically appraised by both the individual and group members involved in a research or community initiative. This participatory approach to reflexivity contends that co-reflexivity “recognizes the complexity of the interlinking relationships connected to historical and current power dynamics and positionality that impact individuals, groups, and institutions” (Gilbert & Sliep, 2009, p. 469). Derived from the co-reflexivity dimension, the activities that we undertook within our CoP were locating ourselves in the collective and developing a charter of guiding principles.

Locating Ourselves Within the Group. Social positioning, built on Crenshaw’s (1989) articulation of intersectionality, is a complex and multi-layered concept wherein oppression and privilege influence and shape one’s socially constructed identity or positionality within societies, social groups, and national borders (see also Weldon, 2016). Locating ourselves in our CoP project was an ongoing and dedicated component of authenticating our knowledge and experiences. Each member was provided with supportive space to share about ourselves, our heritages, journeys, and experiences related to the work of gender justice. This was done through dedicated time at the beginning of gatherings which served to both welcome new members, and allow for a round of sharing, where each members was encouraged to speak. On each ocassion where this check-in was used to open our gatherings, sharing and relationship-building deepened despite our virtual platform and geographic distances. An example of this was the group’s encouragement and celebration of members from Pakistan who were fasting during Ramadan. As new CoP members joined the team, time was allocated for their sharing, which was then reciprocated by existing members.

Development of a Guiding Charter. Essential to the development and strengthening of our CoP was demonstrating transparency in our commitment to an ethical group process. To establish collaborative and open communications across regions, our team generated a document of mutually agreed-upon expectations as a means of establishing relational accountability and commitment to the work (Gilbert & Sliep, 2009). Our Guiding Charter established how our team would commit to a unified vision of supporting one another in achieving our goals for the advancement of violence prevention, healthy relationships, equity, and peacebuilding. The agreed-upon roles and responsibilities of individual team members included overall governance and strategic direction of the project, contributions to knowledge-sharing, leading regional and international knowledge mobilization efforts within the team and community stakeholders, and shared leadership responsibilities of research activities. The Charter evolved from an initial Terms of Reference (TOR), first proposed by the Canadian team, which was cursory and replicated colonial patterns. Attending to power dynamics and the complexities of international partnerships led by Western universities, all partners contributed to transforming the TOR and pushing back on colonial powers. The final TOR outlines partner roles and responsibilities towards the team and decisions on the allocation of funds.

Capacity Building

We adopted Ku and colleagues’ (2009) Triple Capacity Building (TCB) approach in defining capacity building as a mutual relationship wherein all three collaborating groups, students, local communities, and educators take on the roles of teacher and learner. Capacity building acknowledges communities’ capacity to grow and change and is a transformative educational approach that “discovers and mobilizes… strengths… internal resources, past successes, and other positive qualities” (Ku et al., 2009, p. 147). The goal of TCB is to engage all team members in a relational process of knowledge exchange, skill-building, and personal growth. Consistent with our CoP dimension on co-Reflexive relationships, the TCB approach invites all partners to examine their academic and other privileges to confront and collectively challenge these mindsets in participatory encounters (Ku et al., 2009). For example, educators are encouraged to examine their educational privilege in society and challenge these power differences in the relationships formed through the project. From this foundation of anti-oppressive practice, all participants may seek to collectively challenge structures of oppression. Fostering anticolonial and AOP practices and research skills were two areas where our CoP focused capacity-building efforts.

Fostering Anticolonial and Anti-Oppressive Practices. Anticolonial and AOP practices responded to the contexts of CoP participants. Canadian team members focused their efforts on developing appropriate protocols aligned with reconciliation work and our existence as settlers and Treaty People on traditional Blackfoot and Treaty 7 territories. This included territorial acknowledgements, sharing with our regional partners about the Truth and Reconciliation process and 94 Calls to Action (2015), the realities of genocide, the findings of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (2019), and the 231 Calls for Justice. We held dedicated gatherings to consider our various roles and experiences related to colonization and decolonization, led by our project Knowledge Keeper who was a member of the Blackfoot Confederacy. These activities opened space for all team members to consider and discuss how decolonial teachings are rooted in their work and could be further applied to our project and specific regional contexts. Our Knowledge Keeper also committed to opening and closing our webinars according to Blackfoot protocols, providing cultural sharing and reflections at the beginning and end of each event. All partners were invited to share and acknowledge Indigenous and territorial stewards across the participating regions.

The Caribbean team shared the diverse national, cultural, and linguistic contexts and histories within the Caribbean, emphasizing the roles of colonial history, including slavery, indentured labor, and migration, in understanding Caribbean masculinities. A focus on the long-standing and trail-blazing work in the area of men’s gender justice work provided beneficial teachings to members from all regions on possible ways forward. Team members from Nepal invited cultural leaders to share songs and poems and provide historical knowledge and policies in both the Nepali and English languages to contextualize their approach to gender justice work. This included focused time allocated for women from the region to share their stories as survivors, and teachings that informed the group’s understanding of faith and cultural practices within the region. Pakistani team members brought an expansive overview of the region, the intercultural connections, and the religious and Indigenous practices that extend beyond national boundaries. Teachings on the relationships between faith and culture as entry points for transformation were emphasized while underscoring the impacts of colonial invasions and proxy wars on the ongoing work to promote gender justice in the region.

Research Skills Development. Fundamental to our process was ensuring that all CoP members would benefit from their involvement in cross-regional research training. Seminars were offered on narrative inquiry, qualitative interviewing, data collection, data analysis, the Dedoose data analysis platform, digital storytelling (DS), and anticolonial research partnerships. These trainings, which included Q&A periods, provided mentorship opportunities for team members to both share and built their capacities as activist researchers. Students participated in all sessions and were given opportunities to present and facilitate. Further, the seminars were recorded and shared with all members on an unlisted YouTube channel to support the CoP’s planned pilot research initiative and future regional and cross-regional studies (See Appendix B for a list of capacity-building activities).

Community-Consciousness Raising

A core intention of our collaboration was to engage in consciousness-raising across our regions and communities through critical dialogues and knowledge sharing with stakeholders, leaders, and the broader community. Our team viewed community-consciousness raising as an integral step to understanding current social conditions and advancing conscious and transformative action (Freire, 1970, 2005). Paulo Freire, a Brazilian educator and theorist, introduced the widely used educational and social concept of critical consciousness (known as conscientization or conscientizaço), which is rooted in Marxist critical theory (Freire, 1970). The goal of critical consciousness is to fully comprehend the world through an awareness of social and political contradictions. From this, one can then push against the oppressive aspects of one’s existence through conscious action (Freire, 1970; Mustakova-Possardt, 2003).

Sagris (2008) referred to the development of critical consciousness as a form of rupture or emancipation from “domination of what has been taken-as-given” (p. 1), which constitutes breaking from the internalized notions of power and domination. Building on this intention through the work of our CoP, we created a knowledge-sharing platform where interested stakeholders and the public from across the globe could participate in a webinar awareness series on men’s roles in gender justice. Further, a necessary focus on the local contexts within our partnership compelled us to launch local activities within the participating regions, including community reports, infographics, and local seminars, all of which are ongoing.

Hosting an International Webinar Series. The cross-regional webinar series entitled “Men in Gender Justice Virtual Learning Series” sought to stimulate interdisciplinary dialogue with an international audience and share local knowledge on how men around the world are engaging in gender justice work. In total, we engaged 329 participants from 28 countries. CoP members from each of the four regions presented the policies, practices, and social norms impacting gender inequality, and the gender justice efforts occurring within their specific geographic and socio-cultural contexts. Threaded across these presentations was the presence of speakers representing gender and generational diversity, research and experiential knowledge, and academic and community lenses.

The webinars provided a site for cross-regional learning where our project team members were able to share in the learning alongside an international community of attendees. During each session, participants were invited to ask questions and later describe their learnings through an online survey that was distributed after each webinar. All learning sessions were recorded and are accessible educational resources that can be shared within and across organizations, academic forums and classrooms, and with the broader public via YouTube. A webpage was also created through the University of Calgary Faculty of Social Work’s website to provide further information on the project and inspire future dialogue and engagement.

Convening Local Events and Community Reports. In addition to cross-regional webinars attended by an international audience, our CoP team has begun planning local events within our communities to mobilize the findings from our digital story interviews with men who are involved in gender justice work. Team members from each region are creating six digital stories that will be shared through local film nights and posted online to support the grassroots outreach being conducted by the organizational members of our CoP. Understanding that many practitioners and community leaders do not have access to or interest in academic publications, our team developed a brief community report on the project as well as accessible infographics that center the knowledge from each participating region. Due to the enduring global pandemic, many local events continue to be held online.

Knowledge Co-Constructing and Harvesting

Knowledge co-construction and harvesting were practiced through formal and informal methods throughout the CoP process. We adopted these concepts from Brown and Issac (2005), who asserted that the process of “intentionally harvesting the insights… is one essential way that everyone who participates can contribute to weaving bits and pieces of their emerging collective intelligence into a coherent whole” (p. 143). Their World Café conversation methodology provided parallel and community-based language to discuss the qualitative terms of knowledge generation and analysis. While formal research methods were employed to co-construct knowledge through narrative interviews and digital stories with men’s gender justice advocates in each region, this was then complimented by the various forms of informal knowledge harvesting that occurred through continuous engagement within the CoP. CoP members were involved in establishing the priorities and parameters of our virtual gatherings including the content of public webinars, the research questions that would be asked in each region, and research training topics that would benefit the group. We responded to Brown and Issac’s (2005) guidance in creating a hospitable space and exploring questions that matter, wherein diverse knowledges and experiences were valued. Critical dialogue promoted the cross-pollination of ideas, enabling participants to meet and engage with new people (Brown & Isaacs, 2005). This allowed our research to be conducted and mobilized in ways that benefited both academic and community audiences.

Conducting Research. Leveraging the research training and regional knowledge offered through the CoP, members were able to establish a common research agenda and study objectives. We investigated men’s narratives from diverse regional contexts regarding the influences and experiences that encouraged them to become involved in IPV prevention and gender equity initiatives, including what actions, impacts, challenges, and personal changes they experienced. The stories were co-constructed using interviews and follow-up digital stories and continue to be harvested through the mobilization activities discussed below.

Presentations and Academic Journal Articles. Throughout the collaboration, we sought to mobilize the co-constructed knowledge that was harvested through our CoP and formal research process. We presented at two national and two international academic conferences. In these presentations, we focused on sharing the diverse local contexts of gender-based violence that brought our team together, highlighted the local and cross-regional strategies for engaging men in violence prevention, and discussed men’s stories of personal transformation as gender justice advocates. The previously discussed accessible ways of documenting our findings for the benefit of the broader community were complimented by the writing of three academic journal articles. The formal or academic-oriented methods of co-constructing and harvesting knowledge allowed us to contribute theory, practice, and policy recommendations related to men’s participation in gender justice work. Following our principles, all team members are provided with updates on all presentation and publication opportunities, and can then decide if and how they may participate.

Summary

There continues to be a need for anticolonial and anti-oppressive models to deepen the work and impact of communities of practice focused on conducting and mobilizing social justice and practice. In response to this, our team embarked on a two-year collaborative journey that resulted in the design and documentation of an International Community of Practice. As reflected in our framework, the key principles, position statements, process dimensions, and core CoP activities fostered an authentic, ethical, and relational space for international research collaboration and relationship-building. The framework also reflected our shared commitments to anticolonial and anti-oppressive values and principles, and our ongoing learning process. In the discussion, we share our reflections on the impact, learning, and challenges of our approach.

Discussion

Studies that examine the involvement and impact of men’s roles in mitigating the deep and pervasive impacts of gender-based violence and inequity are limited (Carlson et al., 2015; Jamal, 2018; Lorenzetti & Walsh, 2020). Research and practice collaborations are often locally or regionally focused and geared toward addressing secondary and tertiary issues related to intervention with perpetrators and immediate harm reduction. Our cross-regional community of practice presented an opportunity to develop and document the emergent collaborative potential of researchers, practitioners, students, community members, and leaders from around the world who are committed to transforming these issues. By centering anticolonial and anti-oppressive principles and attending intersectionality and relational accountability throughout the CoP process, we worked to interrupt gendered and colonial dynamics that are both a cause and reflection of the inequity and violence present within our communities.

Local knowledge, strategies, and experiential wisdom were given a platform to be shared with an international audience, enriching the project’s ability to reach diverse audiences from 28 countries and informing the collective work of CoP members. Diffuse leadership and consensus-building helped to establish co-ownership of the project and collectively navigate important decisions. Timelines, work plans, and budgets were shared with project members, project money was transferred to the regions for local control when possible, and project information and materials were credited to members from each region. This intentional process fostered a meaningful community and academic partnership built on trust that increased the impact of our research collaborations, including a commitment by participating members to develop a future global study.

In establishing our CoP, we quickly realized the benefits of our existing network in helping to identify potential members. We drew on colleagues, collaborators, activists, and friends of friends who were pursuing male engagement in violence prevention work. While coming together as a CoP, we recognized that men’s roles in GBV were responsive to each regional context; however, the commitment to justice, peace, and equity created a foundation through which we could each join in learning together. As the CoP progressed, our participation in formal and informal knowledge co-construction and harvesting deepened our collective knowledge of the progress and challenges in each region and the cultural, faith, and geopolitical considerations contextualizing the work.

Challenges, Limitations and Framing

Our CoP sought to disrupt structural and relational inequities typically characterized by Global North/South academic and community relations within our research process. However, an explicit evaluation of this intention has not yet been conducted. It is imperative to note that critiques of Western researchers abound, which underscore historical and modern-day practices that co-opt or falsely represent Indigenous and racialized communities worldwide (Mohanti, 1985). The proliferation of funding and peer-reviewed research that uphold this stratification is also troubling (Fals Borda, 1988). Despite our anticolonial and anti-oppressive commitments, our Guiding Charter, and the structure of our CoP, core issues related to the Canadian team’s role as fund holders and the benefits and supports offered to academics located in the Global North institutions were apparent compared to other CoP members. Our proposed framework, benefits, and challenges align with the results of Hakkola and colleagues’ (2020) research, which suggests that a CoP, founded on anti-racist and anticolonial commitments enacted through agreements, can offer a place to practice equity in relationships, provide a space for critical self-reflection, and envision just futures together. However, participants in this same study also advanced the critique that some privileged members of the CoP, despite good intentions, continued to engage in behaviors that replicated oppression (Hakkola et al., 2020).

In our project, one evident point of imbalance was the use of English as the primary language. While all team members could communicate in this common language, first-language users experienced the benefits, comfort, and privileges of sharing their knowledge in a maternal tongue. Informal discussions with some of the members reinforced that there was hesitancy on behalf of certain student research assistants to speak in English in large group settings. Although team leads from the regions made efforts to culturally interpret specific local concepts and traditions from one language to another, this in no way replaces an equitable process where all exchanges would be translated and interpreted on an ongoing basis.

Our identified CoP framework included respect for local contexts, knowledge, and leaders as critical for the formation and maintenance of relationships, and the emergence of strategies and ways forward in our collective work. Members of the team weighed the transnational and geopolitical tensions of upholding this value as both an inroad to social transformation and a barrier to change. The global presence, power and organizing of ultraconservative actors in various formulations (men’s rights groups, “alt-right” coalitions, religious fundamentalists, etc.) cannot be uncoupled from the larger framework of local knowledge and practices; with “gender traditionalism as a form of resistance” …woven into neo-liberal and neo-conservative contextual narratives that position feminism and gender justice movements as a “dangerous regime” (Graff & Korolczuk, 2021, p. 34).

In response, the conceptualization of local wisdom within our project was framed not simply in terms of civic or community-based organizing, which can be fundamentalist and reactionary just as much as it can be solidarity and rights-based. Rather, our approach centralized a set of globally shared principles that have emerged from local experiences of pursuing broader affirmations of human rights, expansion of access to social and gender justice, and transformation of systems established through colonial modes of conquest and control. According to Jamal (2018), sustainable social change requires respectful engagement with community members as both teachers and learners. To facilitate this approach, our research provided a safe space for local men to explore visible and invisible forms of privilege, power, and cultural dominance; The focus of our research was positively engaging for men because it is not begin with labels of ‘perpetrator or abuser’, which is often limits conversation and open sharing. Instead, the notion of being on a journey to improve, grow and become a gender justice advocate opened the space for discussions on personal transformation. Deep reflection on personal experiences of privilege and power is essential for cultivating gender justice. Despite potential challenges, such as recognizing one’s role in oppressive structures and understanding the experiences of the oppressed, this process can lead men to become strong allies in reforming oppressive cultural values and traditions (Jamal, 2018).

Therefore, local knowledges and wisdom are identified and drawn on in this project in ways that advance transnational and intersectional commitments to women’s rights, gender equity, transformation of masculinities, and ending all forms of gender-based violence. In this way, prioritizing local wisdom it is not simply a matter of drawing on civic agendas, movements, and politics, but drawing on those that articulate principles of justice in a manner that is accessible across differences of class, race, gender, sexuality, geography, migrant status, experiences of colonization, and so on. Such an approach is very different from right-wing local knowledge, which is often grounded in stereotypes of an “other,” and hierarchies of rights as well as exclusion from citizenship.

Discussions on navigating these tensions within our local and transnational spaces were sources of collective learning, leading to a broad consensus of multiple entryways to facilitate the ethical disruption of harmful ideologies while remaining committed to uplifting local wisdom and knowledge so as to not contribute to colonial or universalized “know-hows” that are disconnected from context-specific histories and geo-political realities. Through our dialogical process (Freire, 1970), local knowledge, strategies, and experiential wisdom were viewed as sources of cross-national learning and also as political solidarity building, grounded both in everyday approaches to building inclusive communities as well as international frameworks that enshrine equality, justice, and peace.

Closing Reflections

This article reflects our involvement and deep care for violence prevention, gender equity, and a shared resistance to systems of violence across four global contexts. Our international CoP gathered strength and relevance by respecting local knowledges and building on the skills and experiences of our team, enabling us to have far-reaching impacts across diverse communities. This project, which is ongoing, allowed us to highlight and further envision community-based responses within our own contexts. It also enabled our transnational network of researcher-activists to think about how masculinities are being transformed in different contexts, influenced both by transnational feminist movements and a masculinist backlash, in ways related to our specific histories of colonization and decolonization.

Our intention in documenting and sharing this CoP framework is that it may be employed and enhanced through the work of colleagues who are advancing collective and interdisciplinary violence prevention agendas and other social justice collaborations across global contexts. In reflecting on our relational work together within this international CoP, Siegelbalm (2022) comes to mind, “…all we ever had were our passions put to use in the form of communities of practice” (para. 13). From this perspective, it is our hope that sharing our experience may contribute to participatory research and methodological guidance on how CoP frameworks can enrich public discourse and contribute to transformative change for a more equitable world.