Introduction

In North America, youth (defined here as ages 12–24) report the highest prevalence of substance use (including alcohol, cannabis, and illicit substances) compared to adults and are at greater risk of substance use-related harms (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018; Health Canada, 2019; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). Youth have widely different treatment needs compared to adults, especially given the differing developmental and social factors at play. For example, youth are less likely to perceive consequences related to their substance use and experience unique life transitions that influence their substance use behaviors (e.g., puberty, transitioning from adolescence to young adulthood) (Winters et al., 2014). However, evidence-based services and treatments have been largely designed based on adult studies and lack validation from youth (Christie et al., 2020; Winters et al., 2014). Failure to adequately respond to youths’ needs has dire consequences on the healthcare system and their health and wellbeing, as seen by the significant increase in overdose deaths involving opioid and polysubstance use (384% and 760% increase from 1999 to 2018 among youth ages 13–25, respectively) (Lim et al., 2021). To overcome these gaps, peer-led advocacy groups have been promoting the “Nothing About Us, Without Us” motto to stress the importance of involving people who use drugs in shaping the design and delivery of services and policies that affect their lives (Jürgens, 2008). These efforts are critical to not only generate relevant knowledge but to ensure that the response effectively meets the needs of those impacted.

Youth have traditionally been excluded from research given the ethical restrictions in place that are meant to protect them and the rooted assumption that youth have limited agency and expertise to contribute to the research process (Cuevas-Parra, 2021; Langhout & Thomas, 2010). When youth voices have been included, they have often been limited as sources of data, which are mainly interpreted by adult researchers and consequently subject to misinterpretation (Jacquez et al., 2013). Youth participatory action research (YPAR) has been gaining popularity over the last decade in the field of public health and health research to improve the health and well-being of youth by drawing on their expertise (Branquinho et al., 2020; Dunne et al., 2017; Raanaas et al., 2020; Valdez et al., 2020). YPAR recognizes youth as experts of their own lived experience and their ability to identify and solve problems that contribute to their marginalization (Rodriguez & Brown, 2009). Using YPAR methods enables researchers to better understand the health needs of youth by involving them in the design and execution of the research. These methods have also been found to have positive effects on the quality of the research, participating youth, and communities. For example, Valdez et al. (2020) describe how YPAR in substance use prevention resulted in an increased awareness of substance use and effective solutions among youth and communities while fostering skill development (e.g., research skills, decision-making, leadership skills, teamwork, civic engagement, etc.) among participating youth, a common benefit of YPAR (Anyon et al., 2018; Ballard et al., 2016; Shamrova & Cummings, 2017; Valdez et al., 2020).

Though YPAR methods typically assume shared decision-making throughout all phases of research, from its conception to the dissemination of findings (Ozer, 2017), levels of engagement vary widely across studies and phases of research, which dictate the amount of power youth hold over the research (Jacquez et al., 2013; Shamrova & Cummings, 2017; Valdez et al., 2020). For example, completely youth-led PAR projects empower youth to be the main decision-makers regarding how the research is designed and rolled out, while the research team supports youth to conduct research (Ozer, 2017). Meanwhile, partial YPAR studies may only involve youth in certain phases of the research process and/or engage youth in a reduced capacity, which limits their ability to make decisions about the research (Jacquez et al., 2013; Valdez et al., 2020). This may involve collaborating with youth in decision-making rather than making them sole decision-makers, involving youth throughout the process while retaining final decision-making power, or consulting youth for feedback while making the decisions. Potential challenges for consistent, shared decision-making between youth and adult researchers involve hierarchical power dynamics, organizational barriers, insufficient resources, and having to adhere to specific project timelines and funding requirements (Baum et al., 2006; Cuevas-Parra, 2021; Greer et al., 2018).

Continued efforts to engage youth in the research process are important to ensure study impacts benefit those affected by the issue being studied, by empowering youth as agents of social change and justice. Although the results of YPAR studies are abundant in the literature, very few studies report on how to use these methods effectively and address implementation challenges. While practical guidelines for engaging youth in research have been reported (Funk et al., 2012; Hawke et al., 2018; Jardine & James, 2012; Kulbok et al., 2015), the variability of engagement methods used by researchers (e.g., youth advisors, data collectors, co-researchers, research leads) calls for further evidence on how to apply these methods and address common barriers to YPAR. This paper aims to provide practical recommendations to encourage and support other researchers considering engaging youth with lived/living substance use experience as youth advisors and co-researchers by describing our engagement plan, roadblocks, and key lessons learned.

The Experience Project

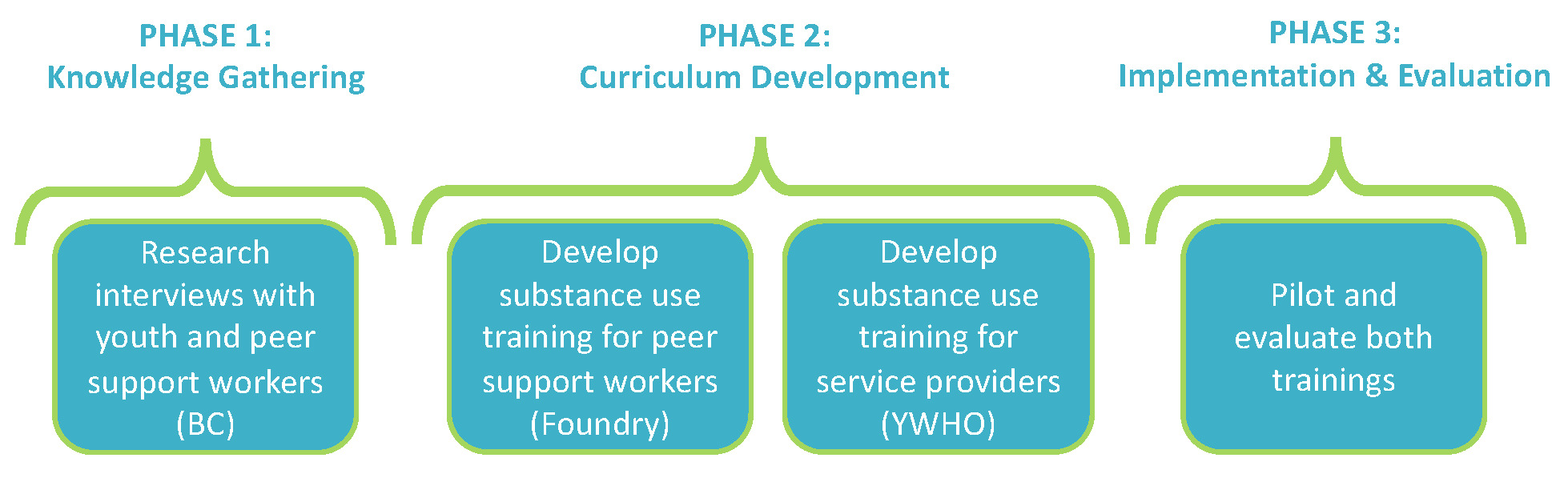

The Experience Project is a qualitative research study that is part of a larger project entitled Building Capacity for Early Intervention, which aims to create youth-informed substance use training for peer support workers and other service providers working within an integrated youth services (IYS) model (Hetrick et al., 2017). The research study aims to support the development of such training by: 1) understanding youths’ perceptions and experiences of substance use services; and 2) understanding the role of peer support in providing substance use services to youth. The project is being led by Foundry and the Youth Wellness Hubs Ontario (YWHO), two IYS networks of centers/hubs in British Columbia (BC) and Ontario respectively. Both organizations share a collective vision that centers youth and family engagement in the design and delivery of services and resources meant to serve them. This project engages youth during each phase, from designing and conducting the research study (phase 1), using new knowledge and lived experience to co-develop substance use curricula (phase 2), and implementing and evaluating curricula impact across the IYS networks (phase 3) (see Figure 1).

This paper will focus on our youth engagement methods during phase 1 of the project, which involved conducting qualitative focus groups and interviews with youth in BC who had lived/living substance use experience and peer support workers who support youth in BC. The full description of the qualitative study methods and findings from the youth interviews have been published elsewhere (Turuba et al., 2022). This paper describes our methodological approach to youth engagement and highlights key learnings and practical considerations for researchers applying YPAR methods when working with this population.

Methods

Youth4Youth Advisory

The BC project team developed a project youth advisory committee (PYAC) made up of 14 youth (under the age of 30), which was later named the Youth4Youth (Y4Y) by advisory members. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, engagement was restricted to virtual methods. Youth were recruited through social media advertisements and targeted outreach, including youth advisory councils from Indigenous-led organizations and rural and remote communities, in order to engage a diverse group of youth. An initial phone call was scheduled to determine fit and provide youth with more information about the opportunity, including a clear description of the project, their role and responsibilities, the time commitment and format (e.g., number and frequency of meetings, work outside of meetings, etc.), and the amount and process of compensation. This information was also provided in a welcome package once offered the position, which also included relevant paperwork to fill out, instructions on how to submit timesheets, tax implications, and how to contact the project team for support. Youth were compensated by honoraria at a rate of $25/hour. When assigning tasks outside of meeting hours, the project team provided youth with an estimated time commitment (e.g., hourly range). If youth needed more time than what was allocated, they were asked to email the project point person to determine whether more time should be allocated for everyone, or if more time was needed for certain individuals due to varying circumstances. The project team sent regular emails and monthly advisory meeting reminders to support youth in submitting their timesheets and getting paid in a timely manner. To determine a standard meeting time, a Doodle poll was sent to the committee, which included evenings to accommodate youth with varying commitments. Meeting agendas and minutes were sent to the group and provided opportunities for those who could not attend the meeting to provide feedback via email.

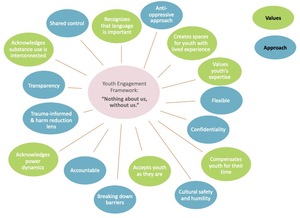

Multiple approaches were used to ensure that the youth felt safe and supported. A youth engagement framework was co-created during the first Y4Y meeting to ensure the project team’s values and approach to youth engagement aligned with those of youth who formed the Y4Y (see Figure 2). The first advisory meeting also involved co-creating a community agreement to ensure Y4Y members felt safe and comfortable to share their experiences, ideas, and opinions during meetings, by asking youth what they should collectively agree on to meet this goal. This included not pressuring youth to share their stories, respecting everyone’s experience and feedback, and maintaining everyone’s confidentiality, given the advisory members’ lived experience. Therefore, we agreed to blind copy youth on all email communications and that permission would be asked before sharing contact information with others. The project team and Y4Y members also agreed to check in before talking about certain substance use topics during meetings to avoid triggering anyone and ensure youth felt comfortable discussing the topic before moving forward. Each meeting began with a community agreement reminder and was referred to when needed. If someone needed to leave the meeting, they were asked to let one of the project team members know so that we could ensure their safety by following up with them if needed.

We also asked youth how they wanted to be engaged to promote a safe and comfortable space for discussion and identified supports needed in place for youth to partake. This involved asking whether they wanted opportunities for small group discussions, written and anonymous feedback, icebreaker activities, and meeting breaks. Further, to ensure youth felt supported and had access to the project team, the phase 1 project lead (author SI) and/or research coordinator (author RT) stayed online after the meetings in case anyone had any concerns to discuss. Individual check-ins were also scheduled between the Y4Y members and the project lead over the course of the study to provide youth with a safe space to share any concerns and foster individual relationships with the advisory members.

Y4Y meetings were held bi-weekly over Zoom to discuss the study design, methods, and materials. This included co-creating and revising recruitment materials and methods (e.g., study posters and outreach lists), screening scripts, consent forms, interview questions, safety considerations and procedures, demographic surveys, follow-up experience surveys, and honoraria format. To facilitate this process, information about the research process (e.g., the ethics review process, recruitment, and data collection methods), was shared during a Y4Y meeting in addition to a focus group facilitation training. Youth independently revised initial drafts of the study materials and provided their input during the Y4Y meetings and/or through email. Youth were asked to ensure the materials and protocol were relevant to youth who have lived/living experience of substance use and to identify gaps (e.g., important questions to ask participants, relevant demographic information to collect, and proper safety measures in place), which were discussed as a group during the Y4Y meetings until a consensus was reached. When feedback could not be implemented (e.g., ethics requirements, organizational barriers), this was communicated back to the Y4Y by the project team.

Youth played an important role in incorporating cultural and identity considerations within the research and creating safe spaces for youth. For example, youth highlighted the explicit need for IBPOC (Indigenous, Black, People of Color) -only spaces for youth to discuss their experiences with substance use and substance use services and supported the development of diverse outreach lists to broadly promote the study opportunity. Youth partners also incorporated questions about the impact of culture, race, and ethnicity on youths’ experiences with substance use services and highlighted the need to acknowledge our current colonial system and its potential impact on participants’ care experiences at the beginning of each focus group/interview.

Youth were also encouraged to take on tasks related to the study that they were particularly interested in and develop their professional skills and strengths. For example, a Y4Y member expressed interest in design and therefore took on designing the study posters to effectively attract study participants. Additionally, Y4Y members were asked if they wanted the opportunity to participate as study participants, given that most met the eligibility criteria. However, this was seen as a conflict by the group given their role as advisors and their relationship with the research team and research assistants.

Challenges that occurred during the study were brought back to the advisory by the research coordinator and youth research assistants (authors AA, AMH, and VB), who were directly conducting the research activities, to brainstorm resolutions. For example, we initially had difficulties recruiting participants to take part in the study; therefore, we asked the Y4Y how we could reach and interest more youth and peer support workers. This led to the updating of recruitment posters, additional outreach, and paid social media advertisements, all of which were successful in increasing recruitment.

The Y4Y was also offered a variety of opportunities to take on more responsibilities for the project, such as supporting research activities, substance use curricula development, and curricula evaluation activities. Each position came with its own onboarding materials and training sessions. Internal requests that matched the committee’s expertise were also brought forward to the group by the project team, including opportunities to inform harm reduction materials, substance use web content, and Foundry’s role in responding to the opioid crisis. If enough members were interested in the opportunity, it was brought forward during one or multiple Y4Y meetings, which were not mandatory to attend. External requests from youth research partners were also brought forward as additional opportunities advisory members could apply for.

Youth Research Assistants

The YRA position description was discussed during a Y4Y meeting and distributed via email. Brief interviews were held with interested advisory members, the research coordinator, and the project lead. Six youths were hired on as YRAs who reported directly to the research coordinator. The onboarding process did not require additional paperwork, apart from a Police Information Check (PIC) to work with vulnerable populations (e.g., minors) and in vulnerable settings (e.g., healthcare). Youth used the same timesheets to submit their hours for both YRA and Y4Y roles and received the same monthly honoraria.

The YRAs received qualitative research trainings to facilitate the focus groups and interviews, which were specifically tailored to the study in question and provided by the research coordinator. The trainings included group facilitation, qualitative research methods, focus group and interview facilitation, and thematic analysis, and involved opportunities for questions and discussions about the material learned. YRAs were also required to complete the standard research ethics training to conduct research with human participants in Canada (Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS-2)). Individual and group practice sessions were held with the research coordinator to build the YRAs’ interviewing and facilitation skills and make final adjustments to the focus group/interview guides. Regular team meetings were also held between the YRAs and the research coordinator to support team building and discuss the study’s progress and hiccups. The research coordinator checked in with the YRAs frequently to inquire about any concerns youth had about the role and provide additional guidance and practice time if needed.

Shifts in project timelines were communicated to the YRAs to ensure they still had the capacity and interest to continue with their role and to manage expectations. As project timelines shifted, the research team made efforts to accommodate the YRAs as much as possible to support their continued involvement. For example, meetings were often scheduled in the evening to accommodate youth with varying school and work schedules, or 1:1 meetings were available if a YRA was unable to attend a team meeting. The research coordinator frequently checked in with the YRAs about their capacity to ensure their workloads were manageable. They were encouraged to let the team know if their capacity changed or if something came up, including exams, doctor’s appointments, and work commitments. Two YRAs left their positions before data collection for reasons unrelated to the study, while another withdrew due to project delays and competing school commitments. The three remaining YRAs co-facilitated the focus groups (n=2) and interviews (n=43) with the research coordinator until they were comfortable carrying them out in pairs or individually. The research coordinator remained on call for supervision or urgent situations even when the YRAs were comfortable conducting the research on their own. Debrief sessions between the YRAs and the research coordinator were held after each focus group/interview to ensure the YRAs felt supported and could resolve any areas of concern.

The analysis was led by the research coordinator, who regularly met and debriefed with a post-doctoral fellow with extensive qualitative research experience. Meetings were held with the YRAs to discuss the data as well as review and refine the themes to strengthen the credibility and validity of the findings given their role as facilitators and lived/living experience with substance use. This included selecting supporting quotes to highlight in manuscripts, conference presentations, and the study’s knowledge mobilization plan, which was also co-developed with the YRAs. So far, the YRAs have supported the drafting of three academic journal publications and co-presented at five conferences, and they will continue to be involved in the dissemination of research findings. See Table 1 for the full engagement process.

YPAR Methods

This study used varying levels of engagement across research phases and throughout the larger project. Youth were engaged in all phases of research, except in the conceptualization of the research question, given the larger project objectives. Drawing on The Spectrum of Public Participation (International Association for Public Participation, 2016), the Y4Y were engaged at the “involve” level by providing feedback throughout the research process, while the YRAs were engaged at the “collaborate” level by directly facilitating research activities and mobilizing the study findings. Still, YRA engagement fluctuated over the course of the study depending on youths’ capacity and interest. For example, although some YRAs expressed interest in taking on a larger role in the thematic analysis, the training and time commitment required was not feasible given their other commitments. Meanwhile, the Y4Y engagement increased to a more “collaborate” level as they began co-creating substance use training (phase 2), demonstrating the fluid nature of this engagement process.

Youth Engagement Evaluation

Mid- and end-point surveys using five-point Likert scale questions were distributed to the Y4Y advisory board and YRAs to evaluate and improve engagement methods over the course of the study. Youth were also given the opportunity to expand on their responses and specifically asked to explain if they ranked any of the statements as “strongly disagree” or “disagree” so that improvements could be made. The Y4Y surveys used repeated measures and asked the youth about their onboarding experiences and their ability to share during meetings, including questions about their psychological safety (see Table 2). The youth engagement framework was also used to develop questions that measured the alignment of the engagement strategy with the values outlined in the framework. The mid-point survey was distributed to the Y4Y halfway through the study and an end-point survey was distributed at the end of phase 1 before moving forward with curriculum development (phase 2). Meanwhile, the YRAs received a separate mid-point survey following their training sessions, prior to commencing the focus groups/interviews, and an end-point survey was distributed after completing the data collection. The mid-point survey asked participants about their onboarding experiences as YRAs, including their training and how prepared and supported they felt before starting data collection, while the end-point survey included questions about their experiences conducting focus groups and interviews and whether the training and support provided was sufficient to succeed in their role. Additional open-ended questions were included to give youth the opportunity to describe their overall experience as a YRA.

The Y4Y and YRA mid- and end-point surveys were initially created by the evaluation specialist (author HT). However, after distributing the mid-point surveys, we recognized a missed opportunity to engage youth in the evaluation process. This led to a Y4Y meeting with the evaluation specialist to discuss the process and opportunities for involvement. Two youth peer evaluators (YPEs) were hired from the Y4Y and were provided with evaluation training, including survey design and evaluation theory. The YPEs revised the Y4Y and YRA end-point surveys independently and met with the evaluation specialist to discuss the proposed changes and make final decisions as a team. This led to slight changes between the mid- and end-point Y4Y survey questions to improve the clarity of the questions and reduce duplication. The value statement evaluation questions derived from the youth engagement framework remained unchanged between the first and second survey administration, as these questions had already been informed by the Y4Y.

Study participants who took part in a focus group or interview were also asked to complete a follow-up survey about that experience. This survey was co-developed with the entire Y4Y as part of the research materials. Using a five-point Likert scale, participants were asked whether they were provided with enough support to participate, how comfortable they felt during the interview, whether they felt heard, and whether they thought the project would make a difference in how substance use services are delivered. Participants were also asked open-ended questions about the strengths of the focus group/interview (see Table 3).

Results

Evaluating our youth engagement process allowed us to improve our engagement methods over the course of the project and initiate the development of an organizational standard operating procedure for engaging youth in substance use research. Seven Y4Y members filled out the mid- and end-point surveys (see Table 2). We did not include the YRA evaluation survey results due to a small sample size (n=3). Meanwhile, 25 study participants responded to the interview feedback survey (see Table 3). Key lessons learned throughout phase 1 of the project and practical considerations for engaging youth as research advisors and co-researchers are described below and listed in Table 4.

Equitable Hiring Process for the Y4Y Advisory

Although we used targeted outreach strategies to promote the Y4Y opportunity among diverse groups and organizations, youth were hired based on a first-come, first-served basis, as long as they met the eligibility criteria and had a genuine interest in the position. Feedback from youth revealed that a more intentional recruitment strategy would have been preferred to ensure diversity among the advisory committee in terms of geographical location, age, ethnicity, and gender identities. Further, youth highlighted the explicit need for IBPOC-only spaces for study participants to discuss their experiences with substance use and substance use services, and the lack of diversity among the project team to support such spaces.

Using these lessons learned, we organized an anti-Indigenous racism training workshop for Y4Y members and project staff to ground the project from a decolonizing perspective. The training allowed us to reflect on our positions as researchers and uninvited settlers and identify important considerations for approaching and engaging youth who have been exposed to poor treatment by our colonial healthcare system. We also implemented another round of recruitment prior to phase 2 of the project, given the project’s shift in focus, and incorporated a short demographic survey with the application process to facilitate a more equitable hiring process. Finally, when hiring youth as YRAs, the project team increased the four YRA positions to six to accommodate all youth who applied and increase our ability to provide safe spaces for youth self-identified as IBPOC. This involved having YRAs who identified as IBPOC facilitate IBPOC-specific interviews at the participant’s request.

Compensation

Youth appreciated getting paid fairly for their time and expertise. As one youth described:

“Using your lived experience for this kind of work can sometimes be triggering and emotionally exhaustive… so compensation helps not only pay people for the time they have taken out of their day, but it also helps affirm the message that their contributions are valuable.” – Y4Y member

Although youth expressed feeling that their lived experiences and expertise were valued by the project team, we faced multiple barriers in paying youth in a timely matter. They had to submit timesheets at the beginning of each month, which was associated with long processing times. Late timesheets were paid out during the following month’s pay cycle, which resulted in many delayed payments. Other barriers included inconsistent mailing addresses among some of the youth partners over the span of the study, leading to further delays and necessary paperwork. Although efforts were made by the project team to avoid such delays, compensation was a source of tension between youth partners and the project team and highlighted our inability to truly form equitable partnerships with youth given the structural barriers in place within the larger organization.

Communication, Transparency, and Accountability

Orientation documents were provided to youth at the beginning of each engagement opportunity (e.g., Y4Y, YRA). Feedback from youth revealed that this was not sufficient for them to fully understand the scope of the project and their role and responsibilities when first starting. While these details became clearer as the project progressed, youth expressed wanting more clarity about the position expectations prior to taking on their roles as Y4Y members and YRAs. Youth also expressed being unsure about who they were supposed to report to, given the overlapping roles between the project lead and the research coordinator and the various youth engagement roles. This led to the development of clear reporting structures that were communicated to our youth partners during a Y4Y meeting and via email for those who were unable to attend. The YRAs continued to report directly to the research coordinator for anything related to their YRA role, while the project lead was assigned as the point person for the Y4Y to streamline all forms of communication to the advisory group. For example, any research related requests for the Y4Y from the research coordinator were communicated over email by the project lead to avoid confusion.

Youth expressed that they felt their voices were being heard and that their feedback was being incorporated into the project. Communicating how youths’ feedback was implemented was crucial to building trust between the youth partners and the project team, which included discussing feedback that could not be implemented and identifying possible solutions. This also enabled us to recommend changes in organizational processes to improve future engagement with youth who have lived and/or living experience.

Safe Spaces

Creating comfortable and safe spaces for diverse youth to share their experiences, ideas, and opinions was essential for the success of the advisory group and overall project. All youth expressed feeling comfortable sharing their experiences and ideas and felt supported by the project team. Initiating the first Y4Y advisory meeting with the creation of a community agreement allowed youth to identify what a safe space would look like and gave the project team something to refer to during meetings if needed. As one Y4Y member described: “I really appreciated creating a community agreement that the group followed and used regularly throughout meetings to provide a safer space for everyone involved.”

Building authentic relationships and trust between the research coordinator and the YRAs was crucial to ensure the YRAs felt prepared and supported in their role. However, safety concerns arose when YRAs had to complete a PIC, which required them to go to a police station. This process caused distress for some of the YRAs given their past substance use and negative interactions with the police. Although the project team would have offered to accompany youth to reduce these anxieties, we were limited in our ability to meet in person due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the various locations where YRAs lived. As such, we encouraged youth to ask a friend or family member to accompany them and checked in with youth following their appointments, while offering to support youth in accessing Foundry virtual peer support services if needed. These challenges were also brought back to the larger organization for discussion, in efforts to change current organizational policies for PICs.

Flexibility

The Y4Y advisory role was designed to provide youth with the flexibility to contribute to the project in whatever capacity they were able and interested in. The flexibility of the group allowed members to take a step back when other commitments or personal issues limited their ability to participate consistently. As one youth describes:

“I am incredibly appreciative of the flexibility with this role for the project because it allowed me to jump right back in when I was ready without pressure of persecution/consequence or exclusion from future meetings. Because of this flexibility, I am able to attend meetings knowing that I am able to bring my best self forward and provide better quality contributions to meetings… It has been empowering being able to jump in when I can and know I am doing good work during those times.” – Y4Y member

Contrastingly, the YRA positions required a larger commitment from youth, therefore the research coordinator frequently checked in with the YRAs to ensure their workloads were manageable and provided flexibility whenever possible. Regardless, not all YRAs were able to continue in their role given other commitments and shifts in project timelines.

Youth Capacity Building

The Y4Y and YRAs described gaining practical professional development skills throughout the project which they “would not have otherwise had access to.” These included skills relating to research, group facilitation, leadership, communication, and professionalism. Further, during slower periods of the study, youth had opportunities to support other projects within Foundry and partner organizations to develop new skills. The YRAs were consulted about their role throughout each phase of the research, including the data analysis and dissemination of findings, to create opportunities of interest that would align with their professional development goals as well as their capacity. The YRAs who were interested in pursuing careers in research and/or health described how their position allowed them to gain practical experience to support future employment opportunities. Youth also expressed that facilitating focus groups/interviews and co-presenting at conferences helped them feel more confident and comfortable interacting with others and speaking in public.

Impact on the Study

Meaningful engagement not only brought value to the youth partners but also had positive impacts on the study itself. Twenty-five study participants completed the feedback survey (see Table 3). All participants described feeling able to freely express their views during the focus groups and interviews and felt that their views were heard. When asked about the strengths or best parts of the focus group/interview, 17 respondents (68%) specifically described positive experiences with the facilitators and 7 respondents (28%) mentioned the youth-informed questions as thoughtful, insightful, and well-rounded. Participants described the YRAs as kind, non-judgmental, and compassionate and felt comfortable and safe sharing their experiences with them.

Discussion

This manuscript reflects important lessons learned while engaging youth as advisory members and research assistants over the course of The Experience Project. The positive impact the Y4Y had in developing the research protocol and study materials was directly reflected in the study participant responses, which specifically touched on the quality and relevance of the focus group/interview questions. This was also substantiated by the positive comments made by study participants during data collection. Further, having the YRAs facilitate these discussions appeared to promote comfortable spaces for participants to share their experiences, although its unknown whether this was partly due to the YRAs also self-identifying as youth with lived experience. This supports the idea that youth are capable of participating as co-researchers and effectively lead focus groups and interviews. Similarly, Damon et al. (2017) found that using participatory methods with people who use drugs helped researchers ask the “right” question and having peer interviewers helped build rapport and reduced social stigma because they were “one of us.”

Youth also played an important role in incorporating cultural and identity considerations within the research and creating safe spaces for all youth to participate. Discussions surrounding the barriers of intersectionality and how this impacts youths’ access to substance services and research participation promoted self-reflection and learning among the project team and enabled us to identify ways to reduce the power dynamics involved between researchers, youth partners, and study participants and decolonize our research practices (e.g., IBPOC-only spaces, intentional recruitment strategies, interview questions about intersectionality and how this impacts service experiences). These outcomes demonstrate how YPAR can support the development of anti-oppressive research practices through its role in amplifying the voices of marginalized populations to drive research and social change (Iwasaki, 2016). Other benefits involved the development of new skills and experiences among youth partners to support future aspirations and employment opportunities, which are consistent with other YPAR studies (Anyon et al., 2018; Ballard et al., 2016; Shamrova & Cummings, 2017; Valdez et al., 2020).

Even though shared decision-making across all phases of research is considered the gold standard of YPAR (Ozer, 2017), these methods require sufficient resources, capacity among the project team and youth partners, and flexible project timelines to execute competently and effectively. It is imperative that researchers evaluate capacity for engagement to determine the suitable level of participation across each phase of research and avoid potentially harmful practices. As such, this study used varying levels of engagement across phases of the research and larger project, which fluctuated over the course of the study depending on youths’ capacity and interest. Youth highlighted the benefits of flexible engagement in order to manage other commitments that impacted their ability to consistently participate as youth partners, demonstrating the benefits of various engagement options and flexibility when working with youth with lived and/or living experience of substance use. This was further demonstrated as three YRAs left their positions before data collection commenced and our need to plan around changes in project timelines and youths’ availability. Other lessons learned included a need for clear, established reporting structures that are effectively communicated to youth partners, and strategies to support varying learning styles to ensure youth understood their roles, responsibilities, and decision-making power within the project.

Although structural barriers can also hinder researchers’ ability to foster truly equitable partnerships with youth, applying these methods can lead to changes within organizations to facilitate these processes in the future. An integrative review of YPAR studies (Shamrova & Cummings, 2017) revealed how YPAR can promote cultural changes within organizations regarding the power dynamics between youth and adults, leading to multiple positive outcomes, such as developmentally-appropriate programs, effective service awareness and advocacy campaigns, and further grant opportunities. Likewise, our lessons learned led to several organizational changes, including hiring policy changes to improve compensation structures and streamlined orientation processes for all youth engagement positions across the organization. This will also facilitate the provision of trainings and professional development opportunities across youth engagement teams and increase capacity across project teams by providing proper organizational structures to support teams with youth engagement. Learnings from this study also promoted the re-assessment of organizational policies from a trauma-informed lens, including recommendations to set up direct PIC processes on behalf of youth employees to prevent potential situations of re-traumatization.

Although YPAR emphasizes the involvement of youth in the conceptualization of the research question (Ozer, 2017), this study was initiated to support the development of youth-informed substance use training as part of a larger grant proposal, prior to the Y4Y engagement. Consequently, the direction of the research was dictated by the funding requirements and overall project objectives, highlighting the competing agendas researchers must navigate when applying YPAR. By standardizing our hiring and orientation practices for youth engagement, we hope to develop a roster of engaged youth within the organization on an ongoing basis, which could facilitate earlier engagement during the conception of research projects. Although this was not possible for this study, our research questions were quite broad, which allowed youth to determine the types of questions we should be asking and how that information would be disseminated and incorporated into the larger project deliverables. The broad research question also allowed for flexibility to tailor the project as emerging needs arose (e.g., Black Lives Matter, COVID-19, climate crises).

Finally, although the youth advisory position was open to youth between the ages of 12–29, we were unable to recruit partners between the ages of 12–15. Interestingly, we faced similar difficulties recruiting study participants within this age group, which could reflect the lack of representation within the Y4Y. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we were limited to virtual recruitment methods and did not have the ability to promote the study in schools which may have also contributed to the lack of interest. Shamrova and Cummings (2017) also found that genuine participation typically involved youth ages 20–25 given the additional resources required to train younger youth, which suggests further research is needed to find age-appropriate strategies for engaging younger youth in research, both as partners and as study participants.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the numerous benefits of engaging youth with lived/living experience of substance use in research. Engagement not only improved the research’s relevance, quality, and validity but supported youth capacity building by fostering youths’ skills and professional development. It also demonstrates how YPAR can promote organizational changes to foster more equitable relationships with youth. The lessons learned and considerations identified throughout this manuscript contribute to the cumulative evidence to support other researchers to engage youth with lived/living experience and overcome barriers to youth engagement.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The qualitative research study was approved by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Behavioural Research Ethics Board (Study ID: H20-01815-A005). The YRAs were co-investigators on the ethics application. All research participants gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

The Experience Project has been made possible through the financial contributions of Health Canada under its Substance Use and Addiction Program. The views herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

Acknowledgments

The Experience Project is grateful to have taken place on the ancestral lands of many different Indigenous Nations and Peoples across what we now call British Columbia. We are also very grateful to the Youth4Youth Advisory Committee whose expertise and time have been instrumental to the project’s success.