Introduction

In February 2020, the United States had its first COVID-19 case; by March, public health officials identified New York City (NYC) as an epicenter of the pandemic with 41,777 cases documented across the city by the end of the month, and hospitals rapidly filling up (Bialek et al., 2020; NYC Health, 2020a). On March 22nd, given the grave concerns of the spread, “New York State on Pause” commenced, and schools and non-essential businesses closed all in-person activities (New York State, 2020). Almost immediately, community stakeholders, including elected officials, began asking questions about whom the virus was affecting and how. Without local or national data on race/ethnicity, or other demographic breakdowns of case rates, hospitalizations, and/or deaths, those considering health equity were concerned there were demographics that might be facing graver risks (Cruz, 2020; Kendi, 2020).

In April 2020, answering the call for more information about disparities, NYC’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH) released the city’s first COVID-19 data broken down by race/ethnicity (NYC Health, 2020b). Though officials and others dubbed the data preliminary, by mid-April the numbers demonstrated that COVID-19 had already exacerbated existing health disparities; while white people represented 18% of COVID-19 fatalities, Latino/a/x and Black people made up 30% and 37%, respectively (NYC Health, 2020c). By June, NYC DOHMH had documented 203,000 cases across the city and was learning more about the disparate impact the virus was having on certain communities, particularly communities of color, residents of low-income neighborhoods, and elderly individuals with comorbidities (Thompson et al., 2020). The Pew Research Center surveyed nearly 9,000 adults across the country and found, in early- to mid-March, that although there were widespread concerns about the potential health impacts of COVID-19, these concerns varied based on race/ethnicity and education level. Black, Latino/a/x, and participants with fewer years of formal education were more likely to respond that the pandemic was “a major threat to their personal health” (Pew Research Center, 2020).

People’s concerns expanded beyond health impacts (Pew Research Center, 2020). Over the course of Pew Research Center’s six-day survey period in early 2020, an average of 70% of participants felt that the pandemic would be a “major threat” to the United States’ economy, with 34% responding it was a “major threat” to their personal finances. These numbers peaked at 77% and 40% in the final days of the survey, suggesting that the more the public learned in those early days, the more collective concerns grew. Similar to concerns about health impacts, there were stark demographic differences in how people thought the pandemic might affect their finances; Black and Latino/a/x people and individuals with lower incomes were more likely to cite greater concerns (Pew Research Center, 2020).

In NYC, a group of researchers, community stakeholders, and leaders knew that beyond rates of diagnosis, hospitalization, and death, there needed to be a better understanding of the direct impacts of the pandemic across different communities. In response, our research team and community partners came together virtually to build the “Speak Up on COVID” project and grounded our emerging research-to-action network in principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR), including facilitating “a collaborative, equitable partnership in all phases of research […] that attends to social inequalities” (Minkler et al., 2012). It was clear that the CBPR approach would aid in exploring these questions, given its focus on important local issues identified by members of the community through an ecological lens that also takes racism, classism, and other critical contexts into purposeful consideration (Israel et al., 1998; Minkler et al., 2012). CBPR has traditionally relied on bringing partners together in person to build trustful and collaborative relationships (S. Z. Zimmerman et al., 2009). However, because of public health authorities’ social distancing guidelines in the context of the pandemic, stakeholders had to come together virtually to develop and implement a CBPR study to understand the impact of the pandemic on diverse New Yorkers.

In this paper, we document our process for collaboratively building a comprehensive but low-burden survey that would answer our community partners’ most urgent questions about the pandemic’s psychosocial impacts on adults across the five boroughs of NYC in the early phases of the pandemic. We also share lessons learned along the way.

Methods

Building the Collaborations

In preliminary phone calls starting in March of 2020, academic partners across our NYC-based health system—representing fields including pediatrics, mental health and psychology, chronic disease prevention, epidemiology, cancer prevention and control, and biostatistics—discussed the need to understand COVID’s impact on New Yorkers in a meaningful, community-driven way. To begin this effort, our team compiled a list of community partners with whom we had collaborated over the past decade and sent personalized invitations to at least 20 organizations for brainstorming meetings hosted in late March/early April. The invitation explained that our health system wanted to collaborate with organizations across the city to build a survey for community members that would assess how the pandemic was affecting their lives. Following CBPR principles, the collaborators would define the rest of the research plan. Almost all those organizations opted in, and several others were invited as the days went on. In the initial meetings, our team created space to acknowledge the pain and confusion the pandemic was causing and asked a series of questions to partners, such as: What do we need to know? Who and what is missing from this conversation? Where do we go from here? An unspoken question remained: Could we build an infrastructure to conduct community-engaged research in a new virtual world?

Based on preliminary discussions, and a commitment to ensure that community and academic partners had an opportunity to work together on all aspects of the survey, we created workgroups: Survey Development; Outreach and Engagement; Tailoring and Translation; Information and Resource Gathering; and Sampling and Analysis. Prior to the initial meeting for each workgroup, we asked members to complete brief surveys through Google Forms that were specific to the workgroup(s) they wanted to join. In these short questionnaires, network participants could indicate if they were interested in co-chairing the workgroup, their availability, and their reasons for joining. Each workgroup also had its own set of tailored questions. Table 1 provides a sample of the workgroup survey.

Within days of the initial meetings, workgroups began meeting via Zoom. Our goal was to develop a community survey along with an accompanying outreach strategy developed in tandem with our community partners. Partners considered messaging they believed would resonate with a plurality of communities, including those they worked with and/or represented, across New York City, strategies to reach such communities, and methods to efficiently translate the survey into nine additional languages. The information and resource gathering workgroup also quickly formed to launch a website featuring vetted, community-focused resources for people to access upon completion of the survey or as a standalone source of information. Once the survey was developed, the sampling and analysis team convened to discuss how the outreach and engagement team’s recruitment plan would impact analyses and identify hypotheses informed by priorities noted across workgroups.

Workgroups had community and academic co-chairs (self-nominated) who were responsible for building meeting agendas, co-leading workgroup meetings, and sending emails to the team-at-large, with the support of a program manager. With no time for comparing calendars, meetings were offered at the start or end of the day, as possible, to encourage participation, with select meetings being held after-hours depending on availability and needs. We provided those who could join the meetings with informal, living agendas that we could amend based on the groups’ emerging priorities and included time to provide updates, receive feedback, brainstorm together, and identify next steps.

Meetings began with brief introductions and an opportunity for members to connect, which felt important because many of our members had not worked together previously. As the group dynamics became more established and people became more familiar with one another, informal check-ins helped with time efficiency and social connection. In meetings, members were encouraged to participate in ways they felt comfortable: sharing aloud, chatting directly with a workgroup chair or the program manager, messaging the group, or leveraging the Zoom reactions feature. They were encouraged to share additional perspectives offline via email or phone.

Those who could not join scheduled meetings received notes afterward, and we solicited feedback via additional Google Form surveys and email while acknowledging an open-door policy. Consensus-building tools were implemented post-meeting, giving everyone a chance to weigh in on important decisions through direct votes and modified Delphi processes. We sent general updates to all workgroups to keep everyone in the research-to-action network up to date, and co-chairs from all workgroups came together on a weekly basis via zoom to build connections and ensure integration across the project.

Later in the process, we also recruited a network of outreach volunteers to help with the promotion of our collaborative project and survey recruitment. This group came together on a weekly basis to track progress in survey completion numbers (paying close attention to a list of ten priority zip codes that were highly impacted by the pandemic), share promising practices for outreach strategies, and troubleshoot hurdles they were facing.

Assessing the Collaborations

This was our first time virtually engaging community partners in a research project throughout the duration of the project. To understand the process from our community partners’ perspectives, we conducted short surveys that were open to all members of the research-to-action network. Near the end of the project, we asked participants to reflect on their involvement with the Speak Up on COVID survey. We asked them why they got involved and asked them to self-assess their level of engagement, rate their perceptions of the importance of community-academic collaborations to the overall research goals, reflect on whether the team listened to community partners’ perspectives throughout the process, and provide additional feedback and insights. We also asked participants to reflect on facilitators or motivators as well as barriers or challenges, and what they might do differently if they were to engage in a similar project or process in the future.

Additionally, we conducted six semi-structured interviews with highly engaged, key stakeholders representing each of the workgroups with some crossover, to obtain more detailed information about initial motivations for getting involved, keys to success, challenges, ongoing motivators throughout the process, and opportunities for next steps. Lastly, we hosted a virtual feedback session with our group of outreach and survey recruitment volunteers to understand their experiences with the project, including perceived barriers and facilitators to their progress and the overall process. We asked outreach volunteers who could not make the Zoom meeting to answer the questions by email.

Results

Collaborative Outputs

Fifty stakeholders responded to our initial inquiry for collaboration, and the network grew to include more than 100 community and academic stakeholders as our partner organizations extended invitations to other organizations, creating a “network-of-networks” approach. The research-to-action network included representatives from various stakeholder groups (ranging from LGBTQ+ individuals and food insecure New Yorkers to small businesses and senior care centers) who represented a wide variety of NYC neighborhoods and had varying prior experiences with CBPR. Together, this diverse group successfully built a survey assessing: demographics; medical history; COVID-related symptoms, testing, diagnosis, and exposures; social determinants of health including transportation, access to care, and perceived discrimination; preventive behaviors; mental health symptoms; resources needed, and more. The survey was available in English, Spanish, Chinese, Arabic, Bengali, Korean, French, Russian, Haitian Creole, and Polish after a rigorous process of translating and back translating, which included checking for cultural nuances in wording.

The survey was launched via a text-to-service (i.e., a text message with a survey link) with recruitment beginning by again leveraging a network-of-networks approach, whereby members of the research-to-action network shared the survey with their constituents and also encouraged their partner organizations to do the same. The survey launched less than two months after our first meeting. Later, we redeployed the survey through a web-based platform (REDCap); we disseminated the survey link through in-person outreach as well as through emails, flyers, and social media posts.

Together, the outreach workgroup created recruitment materials, including a video that communicated the strength of New Yorkers in the face of the pandemic, the importance of sharing stories through data to make change, and the driving purpose for creating the survey: to address COVID-related health disparities.

Additionally, our research-to-action network launched the resource website, including a space for any site visitor to share their questions or concerns, and continuously convened the sampling and analysis workgroup to monitor participant demographics and other characteristics of our study sample and identify important trends in the data. As we tabulated the data iteratively during recruitment, the group also hosted two community-facing town halls addressing topics the emerging data highlighted (mental health, racism, and COVID-19, as well as vaccination), reaching hundreds of people.

Collaborator Feedback

Of the 19 research-to-action network members who responded to our collaborator survey, 16% were other colleagues from within our health system, 74% represented community-based organizations, and 10% represented other academic institutions, themselves, or local advisory boards. The six interviews we conducted were all with members of community-based organizations. Nine outreach volunteers provided feedback through virtual group discussions and follow-up emails.

Project Successes: Building the Network

From the survey responses, one-on-one interviews, and feedback discussions with our volunteers, we were able to identify key themes surrounding motives for getting involved with the Speak Up on COVID survey efforts. The most common theme that emerged was a desire to help during this crucial time by lending skills or expertise. Respondents spoke of their desire to learn something from others while standing with and supporting the community “in a very unnerving time.” They also spoke of the importance of including community-based organizations to inform an effective outreach strategy, help identify language that could be viewed as a trigger or facilitator for inclusion or exclusion, and provide expertise specific to certain communities. For example, one member spoke from their perspective as someone who works closely with LGBTQ youth of color, many of whom are living at or below the poverty line. They noted, “There’s this very sort of fantastical interest in their lives in ways that are not generative for them, and other parts of themselves are not really seen.” Knowing that COVID could have a detrimental impact on their lives, this team member was involved in survey development, outreach and engagement, and sampling and analysis.

When we asked survey respondents to consider their level of engagement with the planning or development of the survey, 74% said they were engaged or very engaged while only 16% shared they were somewhat engaged and another 11% selected neutral. All participants agreed or strongly agreed that collaboration between community and academic partners on the project was important to the overall research goals and 89% of survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the team heard community partners’ perspectives during the process of building and distributing the survey, with 11% of respondents remaining neutral.

Stakeholder interviews reinforced these findings. Interviewees spoke about the equitable infrastructure created to conduct the research. One member said, “I don’t think there was ever an instance where I felt like I couldn’t express my thoughts or be honest with the team, and I think that is probably the same sense of everyone that was in the meeting.” Another stated, “I never felt this sort of weird power dynamic.” Additionally, interviewees reflected on how, despite everyone coming from a different organization and representing a different community, people remained open to others’ perspectives and to shifts in learning, in part because everyone was authentically committed to a common goal of helping people. One participant, reflecting on traditional defaults of protectiveness over ideas that people often resort to in collaborative research efforts, noted, “Everyone put their guard down.”

Participation in the research-to-action network eventually slowed as other work priorities emerged. However, those who stayed involved cited remaining motivated by building new collaborations with diverse partners who were at the table, the adaptability of the project and its ability to stay nimble, the constant learning they were able to engage in, and the clear project goals. As one participant noted, “The city was like on lockdown, and I was home. […] I think this was one of the projects that kept me pushing because it was every day, you know, do this, can you translate this back, translate this… I was always looking for your email […] We had a clear idea of what we wanted to do […] and if you really know what you want to achieve, […] I mean it helps a lot.”

Project Successes: Outreach and Recruitment

When it came to introducing the Speak Up on COVID survey to New Yorkers, our volunteers also noted several successes. They reflected that outreach through social media, specifically Facebook and its various interest- and neighborhood-based groups, was most successful. One volunteer observed, “My best experiences have been through interacting with people in Facebook groups. I can answer their questions publicly and share the survey with many people at once.” Another volunteer shared, “My favorite part of the project was joining Facebook pages and communicating with people that lived in completely different areas of the city from me. I got to get a sense of the neighborhoods and needs of communities that I never would have communicated with otherwise.”

The recruitment volunteers also shared that the introduction of incentives helped with promotional efforts. At first, during in-person outreach, we made hand sanitizers and masks available to potential participants, which, our volunteers noted, invited a change in attitude among people they approached. Our outreach volunteers shared that this even encouraged some people to take the survey on their phones, in the moment. When we added monetary incentives through a raffle, numbers grew even more, and the raffle could be promoted in person or through virtual engagement.

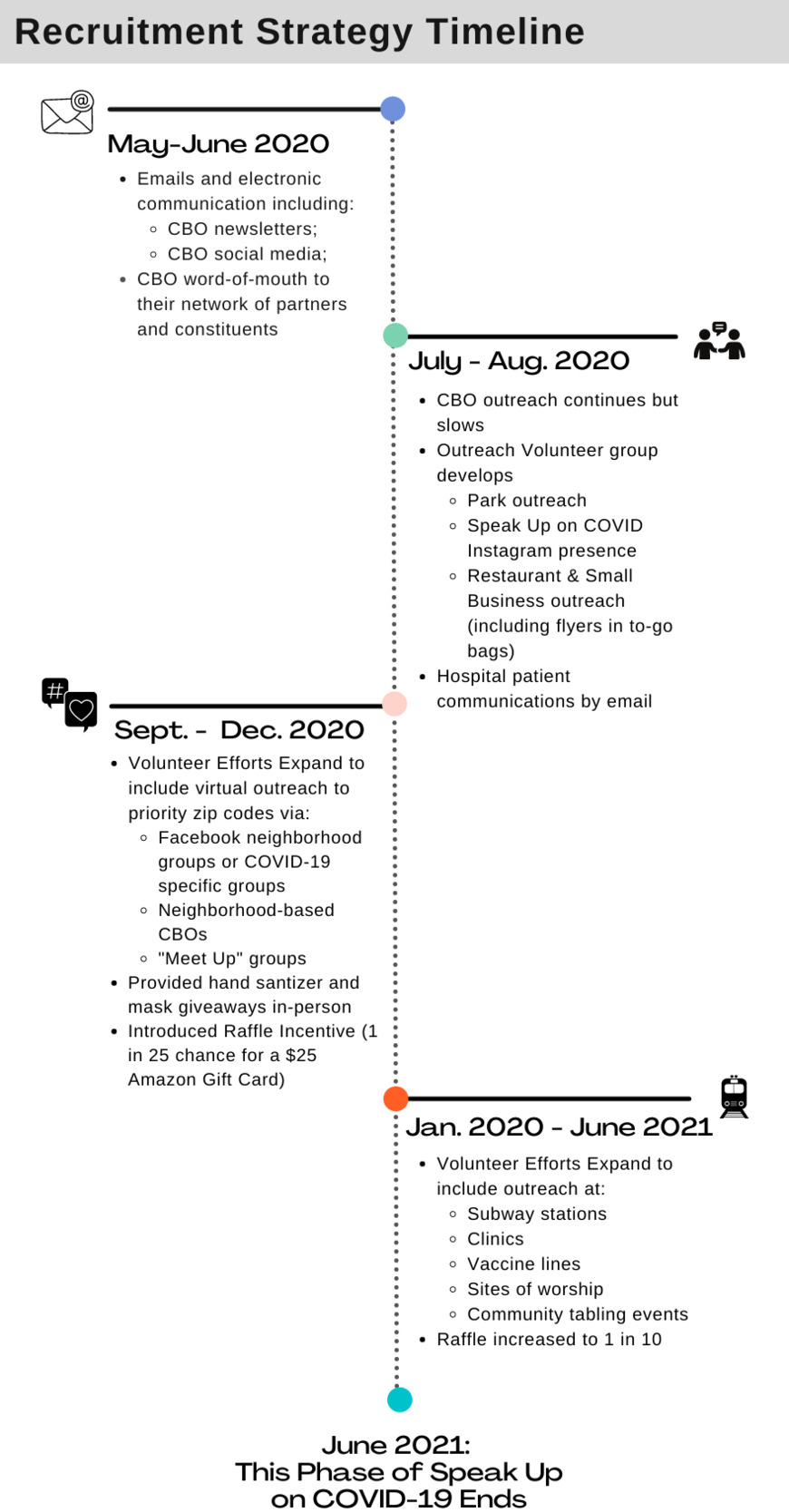

Upon reflecting on the entire recruitment process, one volunteer noted, “The best experience I had on this project was sharing and gaining ideas for outreach during our weekly group meetings. It was great to experience how applying these ideas increased our survey participation numbers.” This group remained intact through June 2021, and together we collected 1,854 completed surveys by revisiting our recruitment strategies along the way, particularly regarding some of the hurdles noted below. In Figure 1, we outline how our community-based recruitment strategies evolved over time from May 2020 to June 2021.

Project Challenges: Recruitment

Despite some of the successes highlighted above, recruitment was a major challenge once the survey launched, and several members of our research-to-action network reflected on potential reasons. Factors included delays in the process due to Institutional Review Board approval, the length of the survey, the time-consuming nature of translation and back-translation of the survey, finding resources for incentives, and developing strategies for distributing incentives without affecting the anonymity of survey responses. Each of these factors delayed the launch date of the survey, which network members suggested may have affected people’s willingness to participate, and resulted in the low early response rate we observed.

While feedback about leveraging social media and other virtual spaces for outreach and survey distribution was generally positive, there were still some roadblocks. Some volunteers reported that proving their affiliation with our health system was sometimes difficult, despite the logo and language on the survey. For example, when our volunteers promoted the survey on Facebook under their personal profiles, some potential participants responded with skepticism. Additionally, our virtual outreach and survey distribution methods at times made it difficult to reach certain populations, including the elderly. One volunteer shared, “[…] This virus hit the elderly really bad, and for this reason, we tried to recruit more of this age group, but the main issue was technical. Most older adults do not have smartphones, and many of those who have them do not know how to navigate the internet, and they do not know how to search Google or deal with the survey layout […]”

Additionally, volunteers found that reaching out to organizations in the most-impacted neighborhoods with whom we had no prior relationship was time-consuming and produced few results. When they began calling and emailing organizations, they found that their inquiries often went unanswered or that organizations did not feel they could effectively reach their constituents since they, themselves, had shifted to online spaces. For some of our volunteers, finding the right gatekeeper to speak to within an organization proved difficult. As one volunteer noted, “I did try calling some organizations as well, but that proved to be unsuccessful because the answering people answering were typically not sure whom to direct me to.”

During the warmer months, we were able to conduct some of our outreach in person, but our outreach volunteers came up against hurdles with this, too. For example, some potential participants were wary. As one volunteer noted, “The fact that we are in a pandemic […] made it hard for people to speak to us or even touch the flyer; people feel scared, anxious, and much mental noise.” This was further complicated by the difficulty of catching a New Yorker’s attention on the streets. However, our volunteers noted that people were less hesitant and less rushed at clinics, in vaccination lines, at election polls, or in laundromats, and these became optimal places to recruit. Although it was at times difficult to anticipate locations that would be the busiest and most conducive to recruitment efforts and some people hesitated to participate due to the survey length, our volunteers noted that incentives significantly helped with in-person recruitment efforts.

Project Challenges: Technology

Another major barrier to the overall process also came to the forefront at the start, when the technology to disseminate the survey failed us. As one community partner noted, “There were difficulties community members faced trying to complete the survey initially, and it was hard to convince people to participate. The glitches impacted people’s desire to collaborate and complete the survey.” The glitch resulted in the team having to move the survey to another platform and redistribute it to our networks, which delayed the timeline but also resulted in community partners feeling frustrated with the process when we had to go back to them and ask them to re-distribute the survey to their clients and partners.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic drastically transformed New York City and left, in its wake, so many questions unanswered. Building a virtual CBPR project to try to answer some of these questions was no small feat but given the scale and scope of the pandemic in our city, our team, including our community partners, felt this was a task worth tackling.

The CBPR Process

In general, CBPR processes take time to build up and deploy (Minkler et al., 2012). Considering the rapid pace at which the pandemic was evolving and the scale of harm it was causing every day as context, the Speak Up on COVID project needed careful management and navigation. Traditionally, one of the most time-intensive, but critical, parts of developing and implementing CBPR projects is team building (Holkup et al., 2004). This is particularly difficult without in-person engagement. However, we were able to overcome this hurdle by leveraging more than 10 years of pre-existing relationships with a variety of stakeholders. When considering whom to invite to our first collaborative meeting, we did not have the typical pressures of identifying stakeholders with specific expertise or areas of focus or feeling confined to working with individuals in certain fields or those who offer particular services. Given that everyone felt COVID-19’s impact in a number of ways, the invitation was open to anyone that wanted to get involved.

That so many partners got involved and remained involved, however, is a testament to the power of shared goals. In any CBPR process, establishing mutually-agreeable goals at the offset is critical (Lopez & Candelario, 2020). While we did have to spend time identifying timelines, developing next steps, and coming to a consensus on a number of topics along the way, we all came to the table with shared overarching goals of understanding how the pandemic was affecting New Yorkers, learning more about how the pandemic was exacerbating health disparities, and creating an accessible survey and strategies to reach disproportionately-impacted communities.

Another important lesson we learned during this process was how critical it is to be flexible as new challenges emerge. In a crisis, people show how adaptable they can be out of a desire to help (Tufts, 2020). However, while having a shared understanding of what stakeholders are trying to achieve and being flexible are fundamental to CBPR, sustained engagement is not a given, and researchers must be intentional about the processes they build for engagement to thrive (Tufts, 2020). Although most partners were not new to us and had been involved with other CBPR projects before, many were new to one another. Therefore, it remained essential to build and maintain trust every step of the way despite barriers associated with being solely online.

The Broader Context

Weeks after we launched our survey, the nation learned of the wrongful murder of George Floyd by law enforcement in Minneapolis (Hill et al., 2021). The Black Lives Matter movement catapulted back into focus with people showing up in streets across the country, including NYC, to protest racism (CNN, 2021). Suddenly, everyone was having long-overdue, and previously intentionally avoided, conversations about racism—including people in the public health and medical sectors who could not ignore the role of racism in health disparities (The Lancet, 2020). Our community partners wanted to talk about this context, explicitly, and so did we. We quickly came together to acknowledge the pain people were feeling and explore the intersections we were seeing between Black Lives Matter and COVID-19. Still, there was tension as we asked ourselves how we might continue to promote the survey at a time when other important conversations around racism, like police brutality, were gaining such momentum. The team was cautious about seeming as though they were co-opting a moment that the nation was feeling so powerfully. However, acknowledging that the system in which racism grows and spreads is a complex one, our partners re-oriented us towards our original goal of understanding how racism would deepen disparities related to COVID-19. This allowed us to realign our priorities and become more explicit in our messaging. We wanted to examine the effects of COVID-19 on all New Yorkers so we could better understand the deep contrasts in experiences we suspected would exist. We continued with the survey, recommitting to our shared goals and making it clear that we were interested in collecting data to inform strategies for addressing such disparities.

Virtual Engagement with Stakeholders

In prior years, researchers attributed successes with virtual CBPR to breaking potential access barriers based on geographic and other factors (Tamí-Maury et al., 2017). In contrast, others have found that CBPR conducted remotely felt more disconnected due to a lack of physical interaction, inadequate technological skills or reduced access to secure internet, and complicated decision-making and other communication processes (Henderson et al., 2013; O’Brien et al., 2014; Tamí-Maury et al., 2017). In response to these challenges, the multiple modes of engagement that we leveraged allowed people to show up in ways that made sense for them as they, too, were getting used to what it meant to transition to remote work during a global pandemic (BBC Worklife, 2020). Our research-to-action network members were feeling what many across the world were also reeling from: uneasy anticipation of what the day’s news would bring, long hours, and limited human interaction. To address these realities, we built structures so that people could share ideas in whatever ways felt comfortable to them. For example, while we scheduled virtual meetings, they were not mandatory and people always had an opportunity to share their feedback through email, a survey or feedback form, or on another call.

We also learned that providing different opportunities and methods for people to contribute not only made the research better but also made community members feel good about the process and motivated them to stay involved despite how hard COVID was on everyone’s daily lives. As one community partner noted, “Well, to be honest, the main thing that motivated me was feeling like I was being heard and that my input was making a difference. I mean, clearly, we all want to do this to help, right. To help this city.”

Despite the multitude of structures we had in place for soliciting contributions and the flexibility we offered for staying involved, the virtual engagement process was not flawless. The constantly-changing context of COVID-19, for one, made it more difficult for community partners to stay as involved, in the long-term, as they would have liked. In the first few weeks of the pandemic, many people’s jobs were in some ways on hold as organizations worked to recalibrate (Vasel, 2021). This may have freed up some initial time for those in our network as they awaited news on how to move forward with their work. However, once it became clearer that pandemic-related work would be continuing over months and then years, organizations made shifts and efforts picked back up, often intensifying as they worked tirelessly to help communities with emerging needs (Maurer, 2020). A few partners, for example, got pulled into test and trace efforts, and many were trying to address other community needs, such as food and financial assistance and health/mental health, and had to limit the time they spent on this project.

Virtual Engagement with Community Members

While we successfully established trust and rapport across our partner network online, it was difficult to translate that to our virtual outreach and engagement efforts, as evidenced by our slow survey response rate. Printing and mailing surveys across the city was unrealistic. In an attempt to make the survey more accessible, we tried to use a text-to technology that we thought would be more straightforward and inviting than sending out a link to a survey platform. However, the texting service failed for a number of people and we had to change our approach, and all of our marketing materials, within a matter of days. Due to this technical glitch, we asked our partners to redistribute new flyers to their constituents, causing them to worry potential research participants might perceive our team as disorganized and that the survey’s reputation would suffer.

Additionally, being restricted to promoting the survey through listservs, social media pages, and other web-based platforms unearthed some challenges around establishing trust with potential survey participants. In our conversations with our outreach volunteers, we frequently revisited roadblocks around messaging and posting the survey link on Facebook pages and in other web groups. Our volunteers suggested we revise our survey by explicitly including our health system’s branding in an attempt to assuage fears about the survey’s legitimacy on the internet. However, despite stating their affiliation with our health system and this revision, participants reported skepticism about the survey. When considering why, one volunteer reflected, “[…] Perhaps the prevalence of internet scams online had people wary of reading messages/clicking links sent over by strangers (understandably). Future work may try to incorporate a way to reaffirm credibility.” In addition, while adding our branding may have been helpful in recruiting some participants, affiliation with a large health system may also have served as a deterrent to others with questions about how health systems conduct research and use research findings.

We would be remiss if we did not acknowledge that other recruitment challenges might have had nothing to do with technology and more to do with the shared exhaustion New Yorkers were experiencing due to the pandemic (Murphy, 2020). By the time the survey launched, we had witnessed several extensions to the NY on Pause measures and the pandemic did not yet seem to have an end date in sight (Plitt, 2020). The COVID-19 fatigue New Yorkers were feeling from the non-stop inundation of COVID-related news and information could have contributed to the slow response rate (Dennis et al., 2020). Additionally, reluctance to participate in research might reflect general skepticism individuals held towards researchers at the time, despite efforts to build trust, especially in the context of COVID-19 and ongoing assaults of racism (Crooks et al., 2021).

Next Steps

Despite the challenges that emerged, the research-to-action network persevered and is still learning, every day, from the results we captured over the many months the survey was live. Though we now meet less regularly, smaller teams of people have remained in touch to analyze and interpret the data and are working hard to disseminate key results. Several of the partners became involved in subsequent initiatives that this work has informed, including community-engaged COVID-19 vaccine equity initiatives and efforts to build community capacity for future CBPR projects. This brings us back to fundamental mutual goals that guide our work. People across NYC and beyond got involved because, as we see in the results, they wanted to help and be part of something bigger than themselves. This remains evident as the work moves forward to inform new policies, programs, and research and helps explain why several partners continue to stay engaged in this work.

An Adapted CBPR Model

Figure 2 depicts an adapted CBPR conceptual model that takes into consideration the many contexts and processes that the team needed to consider, and the collaborative processes, outputs, and outcomes that emerged from our work (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010).

Conclusion

While the concept of virtual CBPR did exist prior to COVID-19, the pandemic left many grappling with and, subsequently, chronicling an array of research processes that had to adapt in the face of the crisis (Valdez & Gubrium, 2020). Some have recognized that the CBPR approach may be particularly well suited to the COVID-19 context, given its emphasis on remaining flexible and in tune with community needs (Tufts, 2020). Despite the abundance of literature on the use of CBPR during challenging times, including in post-disaster contexts, there remains limited publications focusing on how public health crises akin to the ever-evolving COVID-19 pandemic may complicate such research (Fortune et al., 2010; Lichtveld et al., 2020; E. B. Zimmerman et al., 2020).

The collaborative processes we implemented yielded many lessons learned for future virtual CBPR projects, particularly during times of extreme stress, uncertainty, and rapidly-shifting circumstances. We remained true to the core principles of CBPR with a particular emphasis on working towards equity in our infrastructure and committing to processes of collaborative exploration in uncharted territory (Braun et al., 2012). In doing so, our research-to-action network was able to learn not only about how New Yorkers were faring during the pandemic but also how communities can come together and build strong, generative partnerships in trying times. Finally, sustainability in partnerships is critical to CBPR (Minkler et al., 2012). Since the first phases of the pandemic when the research-to-action network launched, we have maintained close collaborative relationships with new and existing partners, finding additional opportunities to work together on topics including building community capacity for research endeavors, successfully executing virtual engagement, and addressing health inequities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Institute for Health Equity Research at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for ensuring this project was possible, and the Research to Action Network that came together to build this effort.

Research reported in this manuscript was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (NEN-1508–32252)