Introduction

This article explores how and why an assemblage of critical, qualitative research methods—using participatory action research (PAR) and constructivist grounded theory (CGT) as the backbones—was constructed and used to study the rapidly-emerging field of public sector innovation (PSI) labs. The origins of this work are rooted in my dual roles as practitioner and researcher in the field of public sector innovation. It is also rooted in my desire to support higher-impact public sector innovation lab practice in a way that is not possible when consumed by the day-to-day pressures of developing and running an individual PSI lab. This dual role and desire, a deep commitment to co-creative research that generates insights useful for practice, and my own views and experiences of what public sector innovation should be working toward, required a research method that harnessed this positional complexity as a strength while providing rigor and quality in ethics, process, and outcomes.

PAR and CGT are appropriate methods for community-engaged inquiry into public sector innovation because they can handle researchers who hold standpoints, a justice orientation, and a desire to produce radical, and democratizing transformation as long as these are transparent, made explicit, and are part of a reflective process (Charmaz, 2014; Denzin & Lincoln, 2017). PAR invites applied and action-oriented knowledge generation, transparent and open co-production of knowledge with/by/for those who are most impacted by the challenges being researched and aims to dissolve the boundary between “researcher” and “researched.” CGT provides a method to find patterns contained in this knowledge, and to craft and shape it into insights, frameworks, themes, and middle-range theory that can support application, knowledge mobilization, building credibility, and making comparisons across the field. PSI labs are diverse, emergent, and contextual, and at the same time have some shared questions and challenges with trying to do innovation work from within the public sector. Some of those questions and challenges became the focus of this research.

When initiating a new PSI lab in my practitioner role, I began by drawing upon my network connections to gather information through web research and informal interviews with twelve established and emerging PSI labs in Europe, Canada, and the United States. Through asking questions about how these PSI labs and leaders were shaping the purpose, form, activities, and impacts of their labs, I gathered a collection of shared challenges and questions held by the field in addition to those in my own practice. Practitioners were individually and collectively trying to figure out how to increase the impacts of the work in a variety of different ways, and to realize the promise, potential, and responsibility held by PSI labs at a moment of rapid proliferation.

The seeds of this inquiry began as hunches rooted in my own experiences and questions as a practitioner and researcher. I then discussed, re-formed, and developed these through conversations with other practitioners. Exploration of emerging academic literature about public sector innovation and labs revealed gaps in research areas that practitioners consider important. Over time, and through ongoing research and reflection with the eventual group of 85 action co-researchers, these hunches evolved into four research questions that guided this work:

-

How might the purpose for PSI labs be more strongly theorized, and why might this be important?

-

How might public sector innovation labs systemically intervene in complex public sector challenges in ways that create stronger enabling conditions for transformative and emergent innovation?

-

What if PSI labs took a transformative innovation learning approach to their work in order to enable and unleash innovation within and amongst individual, organizational, and ecosystem-scale actors?

-

How might the thinking and practices related to measurement, evaluation, and telling stories of transformative change resulting from PSI lab interventions be improved?

Middle-range theory, frameworks, and insights were constructed for each of these questions as a result of this research; however, this paper focuses on the methodological approaches used and how these supported the research objectives and questions. This article briefly describes the field of public sector innovation labs as the context for this work, and then provides an overview of the research design. Details about the five novel approaches taken to assemble the methodological cabinet of curiosities used in this research are shared, describing how PAR, CGT, and several other methodological ingredients were brought together in service of this inquiry. A discussion follows which focuses on four key insights drawn from the design and implementation of this methodological approach, and the paper ends with a brief conclusion. This paper contributes to the existing literature about participatory research methods, particularly studies that aim to generate theory useful for practice while remaining deeply grounded in the knowledge, experiences, and needs of practitioners.

Research Context + Design

What are Public Sector Innovation Labs?

PSI labs are a rapidly proliferating innovation catalyst emerging all over the world and in different types of public sector organizations (PSOs). PSI labs are protected spaces with permission to operate differently than the regular day-to-day norms of the public sector. They work within, alongside, or at the edge of PSOs and use a variety of innovation processes like systemic design, experimentation, and co-creation to change or transform the public sector. The purpose of PSI labs is often described as a need to innovate, improve practice, and add public value by bringing design, creativity, and user-centeredness to the challenges of government (Carstensen & Bason, 2012; de Vries et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2017, 2020; McGann et al., 2018; Puttick et al., 2014; Tõnurist et al., 2017). Gryszkiewicz et al. (2016) capture the essence of a lab as “…a semi-autonomous organization that engages diverse participants on a long-term basis—in open collaboration for the purposes of creating, elaborating, and prototyping radical solutions to open-ended systemic challenges” (p. 84).

With this rapid proliferation comes iteration, evolution, and nuance in the typology of these labs, which Cole (2021) describes as four generations of PSI labs, building on the work of others (Blomkamp, 2021; Carstensen & Bason, 2012; Hassan, 2014; Zivkovic, 2018):

-

Creative platform: focused on employee-oriented ideation processes that aim to create buy-in to trying new methods;

-

Innovation unit: focused on user-centered value creation and using a wider range of different innovation processes and methods;

-

Change partner: centering both users and the organization, and working on the transformation of core public sector organizational narratives and processes; and

-

Systemic co-design: works with complexity through systems practice and social innovation processes. Holds an orientation beyond government itself, recognizing that working with complex challenges requires collaboration and co-creation with multiple partners in ways that share power and responsibility.

The third and fourth generations of PSI labs trend toward more transformative approaches to innovation in the public sector, and also toward working on complex (as compared to simple or complicated) challenges (Corrigan, 2020; Snowdon & Boone, 2007). Many of these third- and fourth-generation PSI labs are stepping into their potential to work toward social and ecological justice, sustainability, and collective thriving. Third- and fourth-generation labs are often testing, probing, and working at the edges of the theories and paradigms that are dominant in the regular day-to-day workings of Western and European governments, and their innovation ambitions and approaches tend to be more disruptive than those focused on making the dominant system more creative or user-centered. There is a depth of practitioner-based intelligence about working in these ways that is not often visible, captured, described, or codified in ways that help the field to reflectively see itself, and to find pathways to deepen both research and practice.

This is a lively, potent, and important site of practice that can be supported by constructing theory through participatory research in three significant ways. First, the challenging work of building stronger theoretical foundations for transformative PSI is not something busy practitioners have the time to do on their own, as the conditions for their practice are already challenging enough. Second, practitioners can not often cannot see the forest for the trees. Although they often look to other PSI labs for guidance and inspiration, this tends to be more about tactics than it is about taking stronger theoretical approaches to support transformative innovation. Researchers can support practitioners in seeing patterns across the landscape of their collective work, enabling practitioners to remain focused on their specific local context and challenges. Finally, theoretically rigorous frameworks grounded in practice can help practitioners to make their work more legitimate, credible, and robust. Ultimately, this results in a higher impact on the PSOs they are working to transform.

Research Overview

Research into PSI labs is only beginning to emerge in the literature. To date, researchers have predominantly taken an arm’s length, observer position in their work, and often choose case study and survey-based (both quantitative and qualitative) methods. They have been most interested in defining, describing, comparing, and codifying PSI labs, with a focus on the innovation approaches and processes that they use, and on characteristics of the role/relationship to the PSOs that they work within (Bason, 2010; Blomkamp, 2018, 2021; de Vries et al., 2016; Lewis et al., 2017, 2020; McGann et al., 2018; Papageorgiou, 2017; Schuurman & Tõnurist, 2017; Zivkovic, 2018). This research is almost always framed within dominant paradigms of governance, as well as within dominant paradigms of “legitimate” or “robust” research in public policy fields, which then shapes their methodology, findings, and analysis. For third- and fourth-generation PSI labs holding a transformative intent, research questions and methods that are constrained within these dominant paradigms limit the types of research questions, approaches, analysis, and insights generated (Brown & Strega, 2015; Smith, 2016).

The primary objective of this research was to support higher-impact, transformative work of third- and fourth-generation PSI labs working on complex social and ecological challenges. This objective was further developed into four sub-objectives. The first was to open up a “cabinet of curiosities,” or a plurality of ways to think about transformative, emergent, and/or resurgent theories and practices of public sector innovation rather than propose definitive conclusions. A second sub-objective was to encourage exploration and imagining around what the public sector might need to be or become in this time of urgent and complex challenges. A third was to understand, capture, and apply emerging practitioner-based intelligence about third- and fourth-generation PSI labs holding a transformative intent. Finally, a fourth sub-objective was to construct middle-range theory and frameworks useful for practice and to generate this theory from both practitioner intelligence as well as from a diverse and interdisciplinary base of relevant theory.

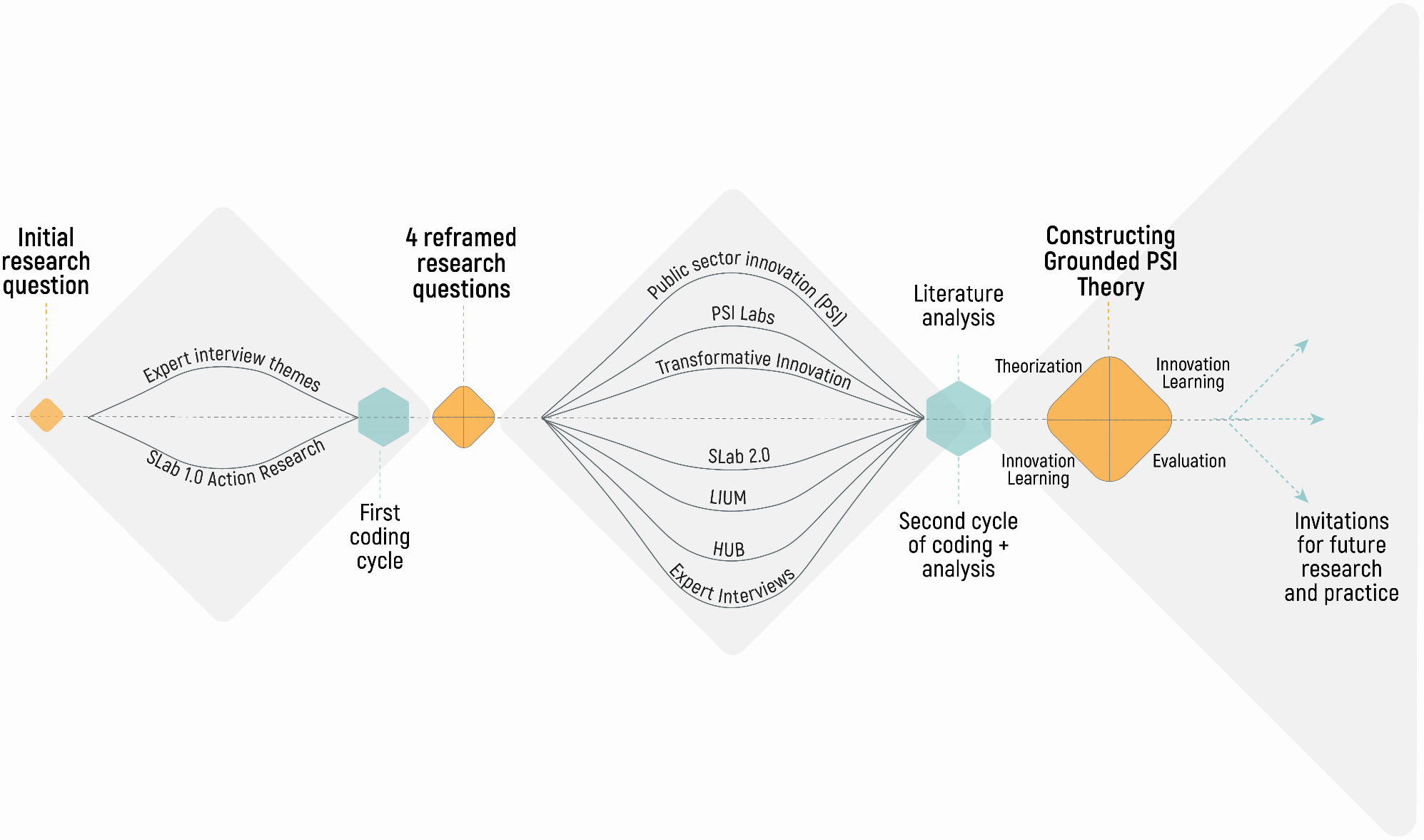

A dialogue between participatory action research (PAR) for data generation and theory testing, and constructivist grounded theory (CGT) for theory building, were the backbone methods in this research (Figure 1) (Charmaz, 2014, 2017a, 2017b; Kemmis, 2008; Reason & Bradbury, 2008; Strauss & Corbin, 1990; Swantz, 2008). Rich qualitative data was generated for theming, coding, analysis, and middle-range theory construction (Freeman, 2017; Merton, 1968; Saldaña, 2016; Timmermans & Tavory, 2012). PAR and CGT were appropriate for this community-engaged transformative innovation inquiry as these methods can handle researchers who hold standpoints, social justice orientation and perspectives, and a desire to produce radical, democratizing transformation, as long as these are transparent, made explicit, and are part of a reflective process (Bradbury, Waddell, et al., 2019; Charmaz, 2014; Denzin & Lincoln, 2017). These methodologies acknowledge that all research holds a perspective and is not neutral, and invite the researchers’ perspectives on data and analysis as relevant to the course of inquiry. Applied and action-oriented knowledge generation and mobilization are built-in, along with transparent and open co-production of knowledge with/by those who are most impacted by the challenges being researched. This made these backbone methods appropriate for this research context, purpose, and objectives.

Research Design

The research design orbited around two central challenges: 1) how to co-create and then explore the research questions described in the introduction in ways that stayed grounded in the experiences, expertise, perspectives, and needs of PSI lab practitioners; and 2) at the same time draw from relevant theory to support practice by adding rigor and robust theory-informed thinking, legitimacy, and credibility. A schematic of the research process is shared in Figure 1 and was generated and implemented through the author’s doctoral research program. A research proposal was developed and approved after the first orienting research question was generated through the author’s own practitioner work, as well as through early web research and interviews with twelve established PSI labs in Europe, Canada, and the United States. In the research proposal, the author: constructed the assemblage of research methods; undertook behavioral ethics review application and approval; described co-researcher identification, recruitment, and consent processes; and articulated two sets of related interview questions (one each for experts and co-researchers at three PAR sites). Co-researchers and experts were recruited through the author’s practice-based participation in formal and informal PSI lab networks and events; this group was not in active collaboration and co-production together around these questions prior to this research. All interviews and coding work were conducted by the author, with insights and results being tested with action co-researchers in a variety of ways, discussed in more depth later in the article.

Eighty-five action co-researchers, working with 25 organizations in seven countries, co-created this research project and the resulting insights. Fifty-four of these action co-researchers were teams working in and with three PSI labs: the City of Vancouver Solutions Lab (SLab); Laboratoire d’Innovation Urbain de Montréal (LIUM); and the BC Government Innovation Hub (Hub). SLab was the primary action research site where I engaged with active work to design, implement, evaluate, and iterate lab activities, and regular interview and observational data were collected from 2016–2020. LIUM and Hub were secondary action research sites in 2019–2020. Action co-research sites were selected and invited into this research based on several criteria: located within and accountable to a public sector organization; include different levels of government and remain within Canada; are early in their development but not brand new and have worked out their structure, role, approach, and activities but were not too fixed or inflexible in their approach; and had capacity and interest to commit the lab team to be active co-researchers. In addition to these, a maximum of three sites were chosen due to available capacity and resources to support the work, and some diversity of purpose, approach, team structure, position in the organization, areas/issues of focus, and resourcing across the three sites was desired. The research questions evolved over time. At the earlier stages of this project, co-researchers were asked about the form, structure, purpose, and underlying values of their lab. Details about the origins of the lab, its position and role in the organization, and enabling conditions and barriers for their work were discussed. Activities of each lab were explored in detail, along with the rationale for choosing these activities and approaches, what was being learned in their application, and how they were evaluating impact. As the research project progressed, research questions became more dialogic and involved sharing and testing the theory in development with the lab teams. Through three site visits each, engagement with lab team activities, evaluation, and strategic dialogue, I was able to collect rich interview and observational data.

The additional 31 action co-researchers consisted of experts working with other PSI labs, each of whom participated in one to two interviews over the course of the research from 2016–2020. Experts were identified and invited into the project using these criteria: hold long-standing experience working in public sector innovation; have strong personal and/or organizational reputations in the field; their current work focus was of direct relevance to this course of study; and diversity of those working directly in a PSI lab and those supporting network- and movement-building in the larger field. These interviews were semi-structured and generally followed these lines of inquiry: 1) What does leading- and next-practice and thinking in PSI labs look like now?; 2) How is the PSI lab community defining innovation?; 3) Where and how is personal, organizational culture, and systems transformation being integrated into PSI lab thinking and practice?; 4) How are values of sustainability, equity, and reconciliation being considered in the work of PSI labs?; and 5) What is the current thinking and practice about evaluation, and how are PSI labs understanding their impacts? Every expert interviewed was also invited to participate in the last cycle of action research to return and test the theory that had been built and to remain transparent and accountable to their contributions as co-researchers.

The research process began with an initial research question in 2016 and moved through one round of expert interviews and a first cycle of PAR with SLab (Figure 2). A first cycle of coding following a CGT approach was conducted, and the research question was reframed into the four fractal questions described in the introduction. From here, an interdisciplinary literature review was conducted alongside active and engaged PAR with the three action research sites and additional expert interviews. Analysis of literature and second cycle coding and analysis of data was conducted. This resulted in theory construction in four areas, as guided by the research questions. As this theory construction was taking shape, an “action research return” invited all co-researchers (including experts) to review and provide feedback before finalizing the work. This was then written up for both practitioner and academic use, along with implications and invitations for future research.

Now that we have established some background about the context, objectives, research questions, participants, and foundations of this research, we will dive more deeply into the theory underlying the assemblage of methods, what each method contributed to the overall approach, and the methodological adaptations and innovations that were made to best support this research.

Assembling the Methodological Cabinet of Curiosities

Although PAR and CGT formed the backbone methods in this research, some choices and adjustments were needed to better respond to the context, objectives, and research questions being explored in this project. This section describes each of the four primary research methods/approaches used in the research design for this project: critical research bricolage; sensitizing concepts; participatory action research; and constructivist grounded theory. These were woven together into an assemblage that integrated methodological insights inspired by different modes of thinking about qualitative data analysis.

Approach 1: Critical Research Bricolage

Kincheloe et al. (2017) say that “a critical research bricolage attempts to create an equitable research field and disallows a proclamation to correctness, validity, truth and the tacit axis of Western power through traditional research… Without proclaiming a canonical and singular method, the critical bricolage allows the researcher to become a participant and the participant to become a researcher” (p.253-4). The bricolage used in this project incorporated a collection of methodologies that: challenged Western ways of knowing by drawing on Indigenous, critical, and feminist paradigms that provided different views into what transformative innovation in the public sector might be or become; allowed for multiple truths to coexist; invited a researcher with an active role in the research questions; and co-created and engaged communities in knowledge production. This bricolage engaged feminist, Indigenous, anti-oppressive, and critical race theory lenses to challenge the ongoing and dominant Western, male, and colonized understandings of the “right” way to do research generally, and also the “right” way to research Western governments, which tend to reproduce narrow ways of knowing and being and limit thinking and exploration rather than open up transformative possibilities (Brown & Strega, 2015; brown, 2017; Celermajer et al., 2021; Charmaz, 2014; Kemmis, 2008; Kimmerer, 2013; Kincheloe et al., 2017; Kovach, 2009; Simpson, 2017a; Smith, 2016; Timmermans & Tavory, 2012; Tschakert et al., 2020).

This critical, qualitative research bricolage enabled engagement with the expertise of researchers and practitioners, generating and testing theory, and inviting the author’s dual roles of researcher and practitioner as concomitant strengths in the inquiry (Castro Laszlo, 2012; Charmaz, 2014; Denzin & Lincoln, 2013, 2017; Kimmerer, 2013; Kincheloe et al., 2017; Reason & Bradbury, 2008). The “critical” aspect of this bricolage revealed possibilities outside of and beyond the dominant paradigms that shape PSI and lab discourse by engaging with interdisciplinary theory (through CGT) in ways that PAR would not have surfaced on its own. The bricolage allowed for divergence, openness, and non-closure when generating insights and findings, a departure from a traditional CGT approach. Holding this bricolage orientation was essential for exploring research objectives and questions focused on transformative innovation on complex social and ecological challenges from within the public sector. A less critical, less engaged/entangled with practice-based intelligence, or more singular methodological approach, would not have generated the types of insights being sought.

Approach 2: Sensitizing Concepts

Blumer (1969) says that human beings act toward things based on the meanings these things have for us and that meaning and interpretation arise out of the interactions we have with others in making sense of these things. The concepts that emerge from critical ideas in social justice research Blumer calls sensitizing concepts. They provide a general frame of reference that suggests directions to explore, questions to raise, and ideas to pursue. Sensitizing concepts offer ways of seeing, organizing, and understanding experiences and ignite thinking. They can provide places to start inquiry, ways to deepen perceptions, and form loose frames and tentative approaches to developing ideas, questions, and processes (Charmaz, 2017a, 2017b). Denzin and Lincoln (2013) write about the researcher as a multicultural subject with a history, research traditions, concepts of self and others, ethics, politics, and their own sensitizing concepts. This framing enables and encourages the researcher to hold standpoints and positions as long as they are made clear and transparent and form part of the inquiry.

The sensitizing concepts that informed choice of, and engagement with, the research methods and questions are shared here. This is done to be transparent and descriptive about how sensitizing concepts were enacted in this inquiry and includes three lenses: individual positionality; role as researcher-practitioner; and sustainability, equity, and decolonization.

Positionality

Charmaz (2017a) describes the dominance of Anglo-North American worldviews and how they pervade qualitative inquiry. Charmaz encourages self-reflectivity about unearned privileges from race, gender, social class, and ability and the effects on personal research approaches, as well as how it shapes dominant research approaches in academia. This sensitizing concept of positionality took into consideration the intersecting identities held by the researcher, as well as by the action co-researchers, and how this informed the frames and paradigms through which the research questions were theoretically understood and practically experienced (Crenshaw, 2017). Power and privileges arising from positionality were considered in the critical research bricolage throughout the process—from the framing of research questions, diversity of action co-researchers, interdisciplinary theories considered, action research processes, data analysis and synthesis, and theory constructed.

Researcher positionality, and the public sector context in which this research took place, made it clear that the methodology would need to attempt to name and make visible the “water that we swim in,” and to suggest additional ontologies and epistemologies that might inform an expanded understanding of what innovation might possibly be—and need to become—in the public sector. Because this research took place within the social structure of Western government and the paradigms and worldviews within which it currently operates, there was strong potential for a PAR-only approach that centered the experiences of current public sector innovators to limit what was seen and understood, and to reproduce what already exists. In order to be aware of a broader set of possibilities and imagined futures, and to bring a fuller understanding of what transformative innovation might mean in the context of government, continuous awareness of (and reflection about) the positionality of co-researchers was required to understand how this affected the research. This reflection took multiple forms, including reading and reflecting, being in dialogue with people holding diverse intersecting identities and positionalities, and actively seeking to learn from the thinking and experiences of Black, Indigenous, and racialized public sector innovators in order to unlearn, unsettle, and stay curious throughout the research.

Researcher-Practitioner

A second significant sensitizing concept is that this research was very intentionally held by, for, and from a very actively integrated researcher-practitioner orientation. Throughout this research, the author was both a Ph.D. candidate and a civil servant responsible for managing a PSI lab, and had specific and distinct responsibilities, accountabilities, and requirements in these two roles. This entanglement offers unique opportunities for research, as well as some aspects requiring close attention, which are briefly described here.

The Ph.D. candidate role involved a research proposal, behavioral ethics review, active and ongoing consent-seeking with research participants, and keeping the identities of action co-researchers confidential. The practitioner role involved a variety of functions, including: conceiving of the purpose and focus for the PSI lab; developing and supporting relationships within the PSO to create enabling conditions for the work; designing and delivering various PSI lab activities; securing funding and partnerships; and evaluating and reporting on impact, amongst others. A few areas required close attention to ensure that this remained an ethical, safe, and productive scholarly space, four of which are discussed here.

-

All action co-researchers were involved as partners and colleagues, and not as people in a reporting relationship to the main researcher-practitioner. This was essential in order to reduce potential power-over tensions and invite open and honest reflection about people’s thoughts and experiences.

-

Using a modified CGT approach for synthesizing and analyzing data was helpful here (and discussed more fully later), as data was brought together as themes rather than being shared more directly as quotes. This helped to ensure that direct or indirect attribution of research data could not be traced back to individuals, organizations, or roles.

-

The author was explicit when they were working primarily as a practitioner (e.g., facilitating a session, collaborating with colleagues on a scoping a project) and when they were working primarily as a researcher (e.g., using a non-work email address to schedule interviews, requesting consent to participate in the research).

-

In the later stages of theory construction and testing, the researcher-practitioner was careful to share when and how these early insights and findings were being integrated into practice-oriented work. This was meant to empower and inform co-researchers as they engaged with the practice-based PSI lab experiences as they were being developed and iterated based on what was being learned and generated through research.

As a sensitizing concept, this researcher-practitioner position was a very productive, rich, and privileged orientation to hold when doing participatory research. It is also a position that requires a high degree of care and attention to ensure that it is done transparently, respectfully, and well.

Sustainability, Equity, and Decolonization

A third sensitizing concept important to this research was holding a purposeful intent, or directionality, of the research toward sustainability, equity, and decolonization in PSOs. As described earlier, not all PSI lab efforts hold this intent; however, this research focused on more strongly theorizing the work of third- and fourth-generation PSI labs working toward transformative innovation. This purpose offered/required methodologies appropriate to this aim, which PAR offered, in part. Bradbury et al. (2019) and Bradbury and Divecha (2020) incite action researchers to move toward a transformative intent in their work in order to support collective thriving on the planet, thus connecting PAR to transformative innovation in a methodological sense.

The very nature of research into sustainability, equity, and decolonization calls to be informed by Indigenous methodologies, as Indigenous Peoples have generations of expertise in living at these intersections. Indigenous worldviews are about being in right relationship with people and place, drawing wisdom from human and non-human ancestors and the land and water, and being good ancestors (Elliott, 2019; Kimmerer, 2013; Simpson, 2013, 2017a, 2017b; Smith, 2016; Tagaq, 2018). Bringing methodologies that drew from Indigenous ways of knowing and being, and from decolonization, into this bricolage supported a stronger interpretation of transformative PAR in response to this sensitizing concept. Kimmerer’s offering that all flourishing is mutual (2013), where humans and more-than-humans live in right relationship to one another, in deep reciprocity with place, and across generations, provides a potent example of how Indigenous methodologies might inform research into transformative innovation and that there are examples of non-colonial paradigms of governance that are present, resurgent, and highly relevant to the work of third- and fourth-generation PSI labs.

Western PSOs are colonial institutions by nature, and it was important to learn how to be informed by Indigenous and decolonizing research methods without romanticizing, appropriating, or misconstruing them in this research. This was attempted by testing research methods and approaches with colleagues versed in Indigenous and critical race theory and lived experiences of these identities, as well as ongoing action, reflection, and learning by the author, who worked to remain in a state of curiosity, humility, and tentativeness throughout the project. There were fruitful explorations and insights about transformative innovation generated by examining the colonial constructs of government and innovation with sustainability, equity, and decolonization in mind, particularly as an increasing number of public sector organizations are committing to policies, programs, and services that advance these objectives.

Approach 3: Participatory Action Research

Reason and Bradbury (2008) define action research as “a participatory process concerned with developing practical knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes. It seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others, in the pursuit of practical solutions to issues of pressing concern to people, and more generally the flourishing of individual persons and their communities” (p.4). PAR focuses on pressing and real-world challenges faced by participants, and is practical, reflective, pragmatic, and action oriented. Researchers and participants actively co-create the research process. This includes generating questions and objectives, sharing knowledge, building research skills, interpreting findings, and implementing and measuring results, including tracking the willingness of co-researchers to act on the results of the PAR. Denzin and Lincoln (2017) add that action researchers help to transform inquiry into praxis or action. In PAR, research subjects become co-participants in the processes of inquiry.

PAR is a family of approaches and an orientation to inquiry, characterized by an eclectic pluralism of sharing, borrowing, improvising, creativity, and mutual and critically reflective learning and responsibility for good practice. For many, it is liberationist and aims to address power imbalances typical of many Anglo-American research approaches. Kemmis (2008) writes about the intersection of critical theory and PAR, and says that “…action research must find a way to work not just on the self-realization of persons or the realization of more rational and coherent organizations, but in the interstices between people and organizations, and across the boundaries between lifeworlds and systems” (p.123). Further, invoking Habermas, he adds that “the organization of enlightenment is best understood as a social process, drawing on the critical capacities of groups, not just as an individual process drawing out new understandings in individuals. Together, people offer one another collective critical capacity to arrive at insights into the nature and consequences of their practices, their understandings, and the situations, settings, circumstances and conditions of practice” (p.127).

The recent evolution of PAR moves even more toward the research objectives in this study. Bradbury et al. (2019) make a call for action researchers to work toward transformation and contribute to a better world. This is then developed further as a set of AR methods that describe ways to do this, including grappling with relationality, reflexivity, interconnectedness, transformation, and complexity (Bradbury & Divecha, 2020). Bradbury and colleagues (2019) describe criteria for valid action research to seek greater rigor, quality, and consistency in using the methods, including: articulating objectives; partnership and participation; contribution to action research theory/practice; methods and process; actionability; reflexivity; and significance. These recent iterations of PAR toward transformation, validity, adaptability, and openness as a method, and the long lineage of researchers engaged with pressing real-world challenges alongside those most affected by them, made action research an obvious choice for a backbone method in this bricolage.

Approach 4: Constructivist Grounded Theory

Building on the foundations, application, results, and critique of grounded theory (GT), Kathy Charmaz and others iterated GT to develop and describe constructivist grounded theory (CGT), the second backbone method in this bricolage (Birks & Mills, 2011; Bryant & Charmaz, 2007; Charmaz, 2014, 2017a, 2017b; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). In CGT, Charmaz acknowledges that the subjectivity and researcher involvement in the construction and interpretation of collected data exists, which departs from her contemporaries who treat GT as accurate and objective renderings of what was happening in the situations that they studied. Constructivist GT recognizes how historical, social, and situational conditions affect both the phenomenon being studied as well as the research process itself, and also acknowledges that the researcher is playing an active role in shaping the data and analysis (Charmaz, 2017a). Charmaz (2014) notes that theory development is the explicit goal of GT, and that purely descriptive accounts are not the purpose. Charmaz (2017a) takes this further and connects CGT to social justice in that together they: “1) take a critical stance toward societal structures and processes; 2) aim for transformation, and 3) demonstrate a strong ethical concern for the individual” (p. 423).

Further to Charmaz’s work in describing the CGT method, Timmermans and Tavory (2012) suggest that by replacing the typical inductive approach to analysis in grounded theory (i.e., generalizing theory from observable data) with an abductive approach, that this may lead to stronger theory. Abduction is “a creative inferential process aimed at producing new hypotheses and theories based on surprising research evidence” (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012, p. 167), or to be led away from old theory to new insights. The reason to do this, they argue, is that abductive reasoning is more likely to be open to, and lead to, surprising and innovative discoveries compared to inductive approaches. The more traditional grounded theory approach, where theory is inductively discovered from the data, does not allow for the richness that can result when a broad, creative, and interdisciplinary theoretical orientation can be abductively applied to data collection and sense-making and more likely result in creative leaps.

These moves place CGT into a potentially productive relationship with PAR, bricolage, and sensitizing concepts. CGT offers something that these other methods do not have on their own—a process that moves toward theory construction and builds generalizations using abductive analysis of rich and diverse qualitative data sources. This bricolage was constructed with these four primary methods and approaches; however, some additional work was needed to skillfully and artfully weave them together to best serve the purpose and objectives of this inquiry.

Approach 5: Weaving Together this Assemblage of Methods

As the critical qualitative bricolage was being constructed, certain aspects were not quite in alignment with the objectives of this work, and in particular the ways in which to work with the qualitative data generated in the research. CGT has a very particular way that data analysis happens (Figure 3). It is a bit like a funnel—the researcher begins with collecting an appropriate amount of qualitative data for their situation while staying informed by relevant theory. As the researcher collects data, they most often code it line-by-line, typically using the first cycle coding methods of initial, process, and In Vivo codes (Charmaz, 2017a). As the researcher works with the data, they constantly compare what they are hearing and seeing with what came previously, going back and forth between data and codes, all while diligently writing memos about thoughts, insights, questions, and emerging categories that arise along the way. As the researcher starts to see some saturation of concepts, they move into second cycle coding which typically uses focused, axial, and theoretical codes in order to move data up to a higher level of abstraction and into categories. This is how the researcher sorts, synthesizes, integrates, and organizes large amounts of data. The categories are worked and re-worked by organizing the codes, sometimes by coding them again, with the ultimate goal of finding or discovering theory that all of the categories and codes can be held within or described by. This approach to working with the rich, qualitative experiences of co-researchers felt reductionist for the purposes of this research, and counter to a more systemic and holistic approach suggested by decolonizing methods. It would also remove the interconnections that were critical to properly reflect co-researcher intelligence and perspectives, and carried a risk of constructing theory that did not meet the purpose of objectives for this research or the needs of co-researchers.

Freeman’s Modes of Thinking for Qualitative Data Analysis (2017) offer a different approach to this process. Freeman explores the different paradigms and points of view that researchers might hold when doing analysis. They describe five modes of thinking for qualitative data analysis: categorical; narrative; dialectic; poetic; and diagrammatic. CGT is firmly categorical: it is about fitting everything into neat, clean, nested categories and creating, or perhaps imposing, order on your data. Diagrammatical thinking was more compelling and promising for the purposes of this research. It was named after a philosophical idea attributed to Deleuze and Guattari about bringing constructs together in experimental assemblages to provoke new or different ways of thinking. Diagrammatical thinking “seeks to disrupt conventional ways of thinking about human and nonhuman interactive spaces or networks. It asks that we look beyond the familiar narrative construction of a story and transverse core aspects of its telling in a way that creates new assemblages of moving and rigid formations, junctures, and concepts. Diagrammatical thinking involves looking at change through intra-acting materializing bodies, rather than through preconceived concepts or forms of classification” (Freeman, 2017, p. 9). In particular, the concepts of intra-acting, staying entangled in the research process throughout rather than trying to get up and above the data, and disrupting conventional ways of thinking were more aligned approaches to data analysis given the other methods in the bricolage, and the ambitions of this research.

This led to an exciting question and possible direction for analysis: what if the overall methods bricolage was reworked and oriented to a diagrammatical way of thinking? Other ways to think about coding and analysis were explored, seeking those that enabled grounding in the PAR data as per CGT approaches, but with a more diagrammatical mindset. Two texts provided insight into how to methodologically approach this question. Saldaña’s Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (2016) describes first and second cycle coding techniques, the transitions between these cycles, and more than 60 different ways to code data. MacLure’s work, Classification or Wonder? Coding as an Analytic Practice in Qualitative Research (2013), was also helpful here. MacLure critiques coding from many different angles and suggests ideas around how to think differently about coding that align well with a more diagrammatic approach. Based primarily on these contributions from Freeman and MacLure, and with support from Saldaña, the approach to analysis typical for CGT was reframed in order to best support this research. This reframe had five elements, each of which is discussed here.

Use Different Coding Types

Rather than using the standard first cycle CGT coding types, Saldaña’s (2016) “eclectic coding” approach was used and modified. Eclectic coding is as it sounds and is essentially a bricolage approach to coding. It “employs a purposeful and compatible combination of two or more first cycle coding methods… appropriate as an initial, exploratory technique…when a variety of processes or phenomena are to be discerned from the data” (Saldaña, 2016, p. 293). Saldaña still thinks of eclectic coding categorically, but a diagrammatical frame made the process more open and flexible while remaining grounded in the data. The specific types of codes that were used, and held within eclectic coding, were: values; evaluation; and In Vivo codes as described by Saldaña (2016).

Two new codes were conceptualized and applied here as well: wonder/emergence; and fractals. Inspired by MacLure (2013), Lichtenstein (2014), and Timmermans and Tavory (2012) the code about wonder and emergence pays attention to what is showing up in between, in the embodied, liminal, and relational spaces. Wonder and emergence disrupt boundaries of power/knowledge, certainty/doubt, knowing/feeling, and animate/inanimate, for example. Recognizing the potential for wonder and emergence in the work of coding might invite moments of indecision on the thresholds of knowing, and from this point something new/else, or something unexpected and surprising might arise abductively. The fractals code was inspired by systems thinking, doing, and being (brown, 2017; Castro Laszlo, 2012; Kimmerer, 2013; Meadows, 2008; Omer et al., 2012). It considers what small pieces of data, or fractals, might tell us about the larger systems they are operating within. Fractals are patterns that exist and replicate across scales; they are wholes within wholes. Fractal coding paid attention to what insights about larger-scale system features and interactions might be held within/by smaller-scale data fragments.

Instead of Categories Use Assemblages to Provoke Thinking

CGT strives toward moving individual codes into higher-order and more generalized categories, whereas diagrammatical thinking suggests the concept of assemblages for grouping and linking. An assemblage brings together diverse elements and vibrant materials of all kinds, without reducing them to one, in order to generate thought. Assemblages are in motion, and they are “sites of potential which open up possibilities for new means of expression, a new territorial/spatial organization, a new institution, a new behaviour, or a new realization” (Freeman, 2017). This idea captures the fluidity, movement, and contextual nature of what is happening with PSI labs much better than trying to fix something within a category. This rich description of assemblages from Freeman was used to guide how data was organized. A tactile and visual approach to coding and generating assemblages (i.e. many sticky notes up on the wall) rather than a digital approach aided in this process as it enabled seeing all of the coded data together in a way that would have been difficult digitally.

Instead of Second Cycle Coding do PAR

Instead of doing additional cycles of focused coding as CGT typically does, the researcher returned to action co-researchers to test, revise, enrich, refine, and discuss what was emerging from the data and generation of assemblages. This process drew from action research, data dialogue, and interactive qualitative analysis processes. It provided additional contextual grounding and lived experience from a diversity of perspectives, and this input resulted in a final revision and iteration of the construction and description of the assemblages for each of the four research questions. This approach helped to gain clarity about what was emerging (in motion) about PSI lab theory and practice that could inform the field at this moment in time, and into the future.

Do Not Seek Saturation, Seek Potential and Possibility

CGT typically seeks saturation of categories to validate findings. As the researcher constructs categories, they go back to their data, or collect fresh data, until they hear repeating information that confirms the categories they have chosen. Because assemblages are not meant to be fixed and definitive, and are instead seeking patterns and possibilities in motion, this process of seeking saturation was not appropriate. Instead of the CGT approach of saturation-as-validity, the following approaches to test validity in this research were taken. First, as early theory emerged from the data, it was tested in a subsequent cycle of action research and literature review. This helped to circle in on emergent theory that was relevant to practice, and that responded to gaps in the literature. To follow the metaphor of assemblages in motion, this process sought a gravitational pull in the direction that the research was moving in. It followed threads of what co-researchers were holding as potent, promising, and provocative as well as the authors’ intuition as researcher-practitioner. Second, two action research returns were conducted toward the end of the research (Fall 2020), with all co-researchers and expert interviewees invited and about half of them participating. This enabled testing for resonance, rigor, and applicability for practice, it generated feedback for theory refinement and future revision, and provided validation of both the research process and results. Finally, the theories generated aim to create a sense of openness, possibility, future inquiry, and experimentation through practice rather than a more definitive “finding,” to support this field in motion and development.

Do Not Seek to Find the One Theory to Rule Them All

The goal of this research was not to “discover” one distinct theory as is typical in CGT. It also was not about trying to get up and above the data in order to gain the perspective required for higher-order abstraction as CGT methods lean toward. The goal was to stay entangled in the CGT-PAR cycle at all stages and to see what emerged while remaining committed to generating middle-range theory that was useful for both researchers and practitioners. Staying with the feeling of being unsettled and unresolved with the data analysis for as long as possible, and not trying to fit everything neatly together at the end, enabled an ongoing openness that was helpful in that it prevented a premature closure of inquiry. MacLure (2013) uses the metaphor of building a cabinet of curiosities, which inspired the integrated approach to method and used as a title for this article. It provides a structure for the assemblages that is not hierarchical or linear while still putting a shape to some patterns, and enables people to interact with what is being produced in their own unique meaning-making ways. The methods aim to provoke plurality of thinking in a certain domain and leave room for people to make their own meaning from what is being shared.

Discussion

The weaving together of this methods bricolage to support stronger community-based theorization of transformative public sector innovation offers learning and insights relevant to other participatory researchers holding a transformative intent in their work. It may also be useful for those aiming to generalize/theorize the results of their participatory research for broader relevance and application, as well as those inquiring into fields and research questions that are emerging or iterating. Four key insights from this approach and what was learned in its application are shared here.

Holding a Dual Role as Researcher-Practitioner was a Strength in this Bricolage

Being embedded in, and accountable to, PSI lab work surfaces different research questions and enables a variety of ways for researchers and practitioners to support one another’s inquiries, rather than a more distant or neutral position. Researcher-practitioners can facilitate active reflection and learning and integrate this learning rapidly into the field. This approach had co-benefits of raising the profile of PSI lab work, validating the work of PSI labs by lending rigor and academic affiliation, and higher-impact outcomes for the real-world work of PSI labs. Co-creating active, engaged, and medium- to long-term collaborations by and for researcher-practitioners using participatory methodologies is a promising direction for further work in this field.

Integrating Critical Theory Opened Up Different Frames and Possibilities

Taking a critical approach to framing research questions, PAR activities, and analysis was critical to get to somewhere different than much PSI lab research to date. This was necessary in order to go beyond dominant frames and paradigms of governance and to open up possibilities from a different vantage point than the dominant ways of thinking and enacting innovation in the public sector. When PSI and labs are studied using methodologies that operate from within dominant systems and structures of power and governance paradigms and from within research methodologies that validate and reproduce relatively narrow ways of seeing, this limits the potential for what research questions are asked, how they are explored, and what “findings” are deemed valid and relevant. This insight may be relevant to those working toward the transformation of dominant systems and structures in other contexts. Relying solely on data and intelligence collected through PAR would likely not have taken this critical view as far as the research purpose and objectives were aiming for.

The Weaving of PAR and CGT was Productive, Fruitful, and Challenging (in a Good Way)

Choosing to layer theory construction through CGT with PAR was a productive pairing given the purpose for this research. Getting to robust and generalizable findings was a key objective, and PAR on its own would not have provided a rigorous enough process to get to the desired middle-range theory. Rich descriptions and case studies of practitioner experiences was not what practitioners needed to be more ambitious and have a high impact in their work, and to progress thinking in the PSI lab field about transformative innovation.

Some important moves were needed to skillfully hold these methods together. Continuing to return to action co-researchers throughout the process to test insights as they were being analyzed, generalized, and abstracted from the data was critical. This was done by framing the initial research question, reframing it into four questions, layering and building on data collection over time, testing emergent themes, and generating theory. A second important move was to stay grounded and committed to being of service, and accountable, to action co-researchers while at the same time bringing new thinking, framing, theory, and possibilities into their view. A third move was to find ways (methodologically) to keep up with a field of practice that is in such rapid motion, and to mobilize the knowledge that is being generated along the way.

Staying with Non-Closure was a Potent and Creative Research Stance

By assembling this as a cabinet of curiosities, it feels clear that staying with the unease, non-closure, and unsettling that was created by inviting and cultivating the plurality surfaced in this cabinet is antithetical to the current cultural norms within the public sector. At the same time, this unsettling is essential when researching and practicing transformative and emergent innovation in the public sector. Employing the research methodologies used here was a helpful way to cultivate openness and exploration when studying PSI labs as they rapidly proliferate, whereas other methodologies can serve the also important work of defining, codifying, and categorizing. CGT and PAR together, with the approach to analysis shared earlier, worked well for this purpose.

Conclusion

The purpose of this research was to support higher-impact work of public sector innovation (PSI) lab practitioners working toward transformative innovation on complex social and ecological challenges. Current research into PSI labs tends to use more arm’s length research methodologies to describe and codify this field, whereas this research aimed to take a much more embedded, entangled, engaged, and directional approach. The assemblage of a critical research bricolage that considered the sensitizing concepts at play in the approach, resulted in a productive weaving together of participatory action research with constructivist grounded theory. Middle-range theory was constructed from action co-researcher data informed by interdisciplinary theories in four lines of inquiry of particular interest and relevance for action co-researchers in this field.

This paper makes an important contribution to the existing literature about participatory research methods. It describes how critical theory and the positionality and purpose of action co-researchers productively shaped the inquiry. It also provides detail about how PAR and CGT work in relationship to one another, and about the adaptations to how analysis was done to both construct theory as well as maintain deep roots in co-researcher intelligence.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Lily Raphael for the design of the original graphics in this article.