Background

UK and International policies acknowledge the need for high-quality, accessible urban green spaces [UGS] and their recreational use as a tool to improve health (Clarke & Wentworth, 2016; Faculty of Public Health, 2010; Natural England, 2003, 2020; United Nations, 2020). Access to green space and the natural environment are important determinants of physical and mental health (Hartig et al., 2014; Marselle et al., 2021). However, within underserved or deprived areas, green spaces are typically fewer, of lower quality, and are areas communities report less satisfaction with (Institute of Health Equity, 2014; Rigolon, 2016; Roe et al., 2016). This reality contributes to the health inequality gap in the UK, with affluent communities enjoying better health outcomes and underprivileged communities having poorer health (Public Health England, 2017).

Physical activity can be promoted if the local built environment features (e.g. connectivity, mixed land use, population density, natural space) are conducive (McCormack & Shiell, 2011). Reviews also show that underserved communities have fewer attributes in their local environments that enhance physical activity, and experience more barriers to participating in physical activity (Wilcox et al., 2002). Local residents can experience barriers to using green spaces due to fears about safety or antisocial behavior (Abbasi et al., 2016; Cronin-de-Chavez et al., 2019; Gidlow & Ellis, 2011). All these issues can further compound the health inequalities faced by these communities. Previous research has shown that families are aware of the benefits of green spaces but their use was interlinked with various structural, community, and individual factors (Cronin-de-Chavez et al., 2019).

Interventions which focus on improving environmental determinants of health, such as provision of green space, have the potential to improve mental wellbeing among multi-ethnic communities. Increasing access to nature may benefit deprived groups the most, and so help to reduce health inequalities (Caperon et al., 2019; Mitchell & Popham, 2008). However, research has shown that the presence of green space alone is not enough to encourage and increase use. Instead, satisfaction with green spaces is a higher predictor of use and subsequent health satisfaction with green space has been found to be a higher predictor of use that brings health benefits (R. McEachan et al., 2018). Evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to improve green space use is still emerging, but interventions combining physical changes with activities to promote green spaces have shown success (Hunter et al., 2019).

Lack of ongoing maintenance can create barriers to use—for example, where vegetation becomes overgrown, equipment is damaged and not replaced, or where vandalism makes spaces unappealing to visit (Cronin-de-Chavez et al., 2019)—particularly in light of the current funding climate in the UK, which has limited budgets allocated to green spaces (Cabe Space, 2006). Within this context, community ownership is a particularly valuable tool in the ongoing maintenance and subsequent use of these spaces (Heritage Lottery Fund, 2016). There is also evidence that co-designing spaces with communities is vital to ensure that they fulfill local needs (Roberts et al., 2016). In this study, we use the well-established definition of co-design as the collective creativity of designers and people not trained in design working together in the design development process (Sanders & Stapper, 2008). Co-design approaches have been used in various ways to elicit valuable and beneficial outputs for communities (Cinderby et al., 2018). Co-design can enable improved engagement by allowing developments to be framed by the reality that urban residents experience (The Mobility of Mood and Place research team, 2016). Such engagement has the potential to allow for the exploration of many perspectives and lead to innovative solutions that better meet participant needs within the constraints of urban areas (Carolan, 2010; Cornwall, 2008). Co-design employs a range of methods and tools to allow a range of participants to contribute (Bagnoli, 2009; Cruickshank & Coupe, 2013). Also relevant to our research on designing green spaces is the extensive body of research on using co-design to build neighborhood plans as has been done with all age groups to build healthier cities (Winge & Lamm, 2019) and in many urban contexts (Pettit et al., 2015; Remesar, 2021). These approaches all include community consultation in the design of urban spaces with the aim of meeting community needs and designing better spaces.

There is increasing recognition of the importance of active involvement of local communities in the co-production of changes, including co-design, to local environments to improve health and wellbeing (WHO, 2017). Making improvements to how UGS are maintained, co-designed, and owned by local communities has the potential to reduce health inequalities if they focus on areas in greatest need (Remesar, 2021). Therefore, this study explores how community involvement in the maintenance, ownership, and co-design of UGS can enhance satisfaction with, and increase the use of, green spaces and subsequently the overall health of the communities which use them.

Our study takes place in an ethnically diverse and economically-deprived urban area within three electoral wards in which the Better Start Bradford program operates. It’s located in Bradford, in northern England. The Better Start Bradford [BSB] program is funded by the National Lottery Community Fund over 10 years, 2015–2025. The program aims to improve the outcomes of children by commissioning projects and services aimed at pregnant women and families with children under the age of 4, focusing on key outcomes of social and emotional development, language and communication, and health and nutrition. Engaging families with these projects and services, as well as with key program messages promoting healthy child development, is therefore crucial to the success. This study engages participants from the three electoral wards in which Better Start Bradford operates to explore key themes around their use of green spaces.

Research Aims and Objectives

This project aims to explore how community ownership, co-design, and maintenance of green space affect the use of UGS for health benefits. The study has the following objectives:

-

To explore the extent to which communities in the Better Start area engaged with green space co-design activities, how the co-design process worked, and whether they were satisfied with the process

-

To explore to what extent community involvement in co-design, maintenance, and ownership impacts the use of urban green spaces for health benefits

-

To consider which mechanisms exist (or don’t exist) that enable community engagement in the co-design, ownership, and maintenance of green spaces, and which mechanisms would be beneficial to develop in order to promote the use of UGS for health benefits.

This evaluation uses a multi-method longitudinal qualitative exploration over three years in four case study green spaces across the Better Start area. We will use qualitative methods in the form of transect walks with photovoice and focus groups to ask community members about their perceptions of their local green spaces and natural environment. We chose to include focus groups in our methodology as they provide community members with the opportunity to share ideas, reflect on the previous stages of the research (photovoice and transect walks), and provide collective discussion and input. In addition to the more conventional method of focus groups, we decided transect walks and photovoice were particularly appropriate methods for this study.

Transect walks are an established participatory research method used to gather deeper geographical context about a location through an interactive discussion between interviewer and participant (Mahiri, 1988; Maman et al., 2009). These involve participants walking with a researcher in a space and sharing their perceptions and perspectives on different aspects of the space, usually areas or observations in the space which are significant (positive or negative) to the participant. Transect walks allow participants to be prompted by what they see and experience in spaces familiar to them and will also take place in spaces where participants feel comfortable exploring with the researcher. Transect walks change the perspective of the researcher who, unlike in other research methods, acts as an observer in a space they are likely to be less familiar in than their participants (Chambers, 1997). The visual focus of transect walks allows researchers to inspire deep understandings of different concerns and allows for a mutual interchange of knowledge between researchers and participants (Hamdi & Goethert, 1996; Juarez & Brown, 2008; Kanstrup et al., 2014). Furthermore, the method is simple, practical, and flexible—working across language barriers, such as those that exist between our researchers and participants (ParCitypatory, 2017).

Photovoice will allow our participants to take photographs to illustrate aspects of significance, in this case within the urban green spaces, that they would like to draw attention to or discuss. The photographs taken by participants will then be used to spark discussion with participants as well as with other community members later in the study, during the focus group. Photovoice is a well-established method to enable participants to record and reflect on their community’s strengths and concerns and to promote critical dialogue and knowledge about important issues through the discussion of photographs (Wang & Burris, 2016). Photovoice allows participants to communicate with photographs as well as words. It also allows outputs to be used to track change or be presented to stakeholders such as politicians, other community members, or decision-makers in local authorities, providing a platform for discourse (Wang & Burris, 1994). Photovoice allows participants to collectively produce a portfolio by reflecting on and discussing community issues (Budig et al., 2018).

Our overall output will be recommendations for improvements to the development and long-term ownership, maintenance, and co-design of green spaces by communities in Bradford so that they can bring about maximum use—and therefore maximum health benefits.

Study Setting

The City of Bradford, in the north of England, has a need for clean, safe green spaces for its diverse population. Our study is set within three underserved electoral wards in Bradford, each of which have diverse ethnic populations (Dickerson et al., 2016). Community consultations completed by BSB to inform their program have highlighted improvements to the local environment (especially better places to play, live, and be active) as key priorities to improve the health and well-being of families in the area.

BSB commissioned the Better Place project in 2017 to work with the BSB community to co-produce and co-design a program of capital improvements to UGS with local communities. The goal was to improve health behaviors and the overall well-being of local families. Better Place has been implementing co-designed spaces, such as urban farms and new play areas, in the BSB wards since 2018 to improve urban outdoor spaces and encourage greater use by pregnant women and children under age 4. This study evaluates the co-design processes used by Better Place to plan for some of the green spaces and the resulting spaces

This study takes place within four predefined local green spaces in the BSB area. These areas have been selected because they have been identified for investment to make positive changes to local environments, and/or where co-design of these changes has been identified as a priority by Better Start Bradford. Participants within each site will be accessed using strong existing community network links facilitated by BSB. This research evaluation will be led by the Better Start Bradford Innovation Hub, the research and evaluation partner of BSB.

Methods: Study Design

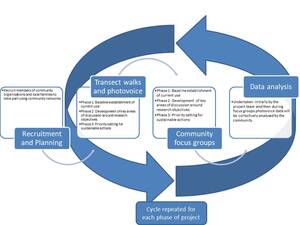

Data will be collected over three phases, each of which will take one year. Phase One (2021–2022) involves recruiting and working with local families and members of local organizations to establish a baseline by collecting data on their use of local green. Phases Two (2022–2023) and Three (2023–2024) involve building on the baseline data collected using the same methods to build a picture, changes in perception, and use of green space over time, allowing for priority setting for the future use, maintenance, and ownership of the four identified green spaces. The phases of the project, and corresponding research methods to be deployed, are outlined in Figure 1. Within each of the three phases of the project, we will conduct transect walks with photovoice and community focus groups.

Transect Walks and Photovoice

Within each phase, a total of 6 transect walks will be conducted at each of the four sites [n=24 per phase] (see Figure 2 for sample breakdown). A member of the research team will obtain informed consent and basic demographic details for each participant prior to commencing the walk-along interviews. We will pilot the proposed methods with a subsample of participants to refine our recruitment and interview procedures. Throughout the transect walks, participants will be encouraged to take photographs of locations they find particularly relevant to the discussion. Participants will use the PicVoice app, already downloaded onto a research tablet or smartphone, to take photographs. The PicVoice software is simple to use and every participant will receive a briefing prior to the walk (see Appendix 1). In the app, participants can record brief audio clips to accompany a photograph they take. During the walks, participants will be asked to focus on elements of the green spaces which are relevant to the maintenance, ownership, or co-design by the community. A guide for the transect walks is shown in Appendix 1. Discussions of these areas, and of the areas which are photographed, will be recorded on an audio recorder. Transcriptions will be conducted by a bespoke transcription service and/or members of the research team.

Participants will be encouraged to take photographs to illustrate their understanding of these three core aspects in relation to the green spaces. Before the walk takes place, an initial visit will be made to the participant to explain the study, obtain consent, and discuss a walking route so a risk assessment can be carried out before the walk. Participants and the research team will agree on the walking routes in advance to ensure routes include key areas of interest (e.g. local parks and green spaces, physical activity venues) while allowing participants to curate their own walk through their local environment. In the event that face-to-face transect walks cannot be safely conducted, for example in the case of remote activities due to COVID-19, participants will be remotely supported to undertake a transect walk themselves, taking photos on these walks according to the training received from the researchers.

We will ensure that individual participants are not identifiable either in community or stakeholder reports or in academic presentations and publications. If face-to-face walks cannot be safely conducted, we will use video-conferencing software to conduct interviews virtually.

Community Focus Groups

Following the transect walks in each phase, one community meeting workshop will take place at each of the four sites. Each workshop will involve 10–12 participants who will be sampled using the framework in Figure 2. A guide for conducting the focus groups can be found in Appendix 2. During these workshops, participatory methods such as problem/solution trees and empowerment mapping/participatory mapping will be used to tease out and support discussion of the key research questions. Problem tree analysis (also referred to as situational analysis or problem analysis) allows participants to build a graphical representation of an existing problem and its causes and effects, and aims to develop a clear and shared understanding of problems faced by participants (Snowdon et al., 2008). Empowerment mapping, or participatory community mapping, originates from participatory rural appraisal an empowering, a method by which communities map their level of involvement in a specific activity, task, event, or situation. Empowerment mapping can map changes over time; this aspect is particularly relevant and useful for studies where changes can be tracked, such as this three-year longitudinal study.

We will use photographs from transect walks to map key areas of interest and spark discussion during the focus group sessions, thereby allowing the present community to contribute to the data. Aspects of maintenance, ownership, and co-design of the green spaces will be discussed along with mechanisms to develop and improve community engagement. The workshop of each phase will be built upon in the subsequent phases, building cohesion across all three years. In the event that face-to-face workshops cannot be held, we have identified software such as Jamboard (from the Google Workspace platform) to enable us to conduct the workshops virtually over Zoom. Tools like Jamboard enable facilitators to add and pin virtual post-its and facilitated virtual workshops effectively.

Sample and recruitment

Eligibility Criteria

Our sample will include: 1) local families; and 2) members of community organizations, including “friends of” groups. “Friends of” groups are groups of individuals from a community who volunteer their time to take care of and maintain local green spaces. We have identified members of community organizations and local families as participants in order to investigate local community perspectives on local green spaces. Families will include pregnant women or families with children aged 0–4 living within the Better Start Bradford area and preferably within the geographical study area of one of the four green space sites identified for investigation. This is our target population because they are the target population of the Better Start Bradford program. We will aim to be reflective and inclusive in our selection of families by using purposive sampling and will provide support in different languages if required. This strategy will ensure we have ample representation across all four areas. Our inclusion criteria for local families are: a parent or caretaker of child aged 0–4 or pregnant women; resident in BSB area, and preferably within geographical study area; willing and able to walk through the local environment with a member of the research team. Our inclusion criteria for members of the community association are: member of an organization (formal or informal) which actively operates within the community close to one of the four identified green spaces for investigation; resident in BSB area; willing and able to attend a community workshop.

Sampling

Size of sample

We plan to recruit up to three members of community organizations and three local families for transect walks with photovoice in every phase (these can be the same or different participants from previous phases, though we will try to re-recruit the same participants at every phase to provide continuity). We plan to recruit between 10–12 community participants from each site for a focus group at each phase. Thus, the minimum sample size will be 16 participants per site (combining minimum focus group and transect walks participants) per phase, amounting to 64 total participants across all sites per phase. We intend to recruit participants until we reach the data saturation point. See Table 3 for a full breakdown.

Sampling technique

We will use a snowball sampling technique capitalizing on our strong community network links within both study areas. In order to ensure that we obtain a varied sample, we will select initial participants with diverse characteristics. We aim to recruit ethnically diverse participants, with equal numbers of males and females, a range of ethnicities, ages, and a range of families with children, including families with children under the age of 4 which will be reflective of the study settings. A substantial number of families in these areas may not speak English as there is a significant number of migrant families in the area, primarily of South Asian origin but increasingly from Eastern European areas as well. We will work with multi-lingual researchers to ensure that we include participants who do not speak English. Our team includes researchers who speak Urdu, Mirpui, Punjabi, and Spanish. We will work with local organizations to identify other language needs and do our best to support the inclusion of these participants. Our snowball sampling will begin with members of our existing diverse community networks who are based within the study sites, ensuring we approach both male and female participants from a range of ethnic backgrounds. While we aim to keep the same participants for each phase in each site, we will recruit new participants at each phase if necessary.

Recruitment: Sample Identification

Transect walks and semi-structured interviews

Potentially eligible participants will be approached either by a member of the research team, a member of the BSB team, or via established community organizations located in the study area (e.g., primary schools, children centers, or community centers). Interested participants will be given a copy of the information leaflet. For participants who do not speak English, a member of the research team or community organization staff will walk them through the information sheet. If a member of the research team is not present, we will ask community members or community organization staff to record contact details of interested participants to be passed on to the research team. We will leave study leaflets and posters in prominent community locations and will publicize the study on social media platforms. We plan to give one voucher per family per interview and transect walk for their time.

Community Workshops

Community workshop participants will be members of community organizations in the specified site and will be recruited via established community organizations located in the study area (e.g. primary schools, children’s centers, community centers). Interested participants will be given a copy of the information leaflet. For participants who do not speak English, a member of the research team or community organization staff will walk them through the information sheet. If a research team member is not present, we will ask community members or community organization staff to gain consent to record the contact details of interested participants to be passed on to the research team. We do not plan to give vouchers to members of community organizations but will reimburse any expenses incurred by participants as a result of taking part in the study.

Consent

Informed consent will be obtained by the research team prior to the transect walks, semi-structured interviews, and workshops. For participants who are unable to read or write (or unable to read study documentation in English), we will read out the participant information sheet and answer any questions the participant has before recording consent verbally on a digital recorder. Participants will have the chance to consider the participant information sheet, ask questions, and seek clarification about the study before providing informed consent.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data will be analyzed using thematic analysis (TA), a widely-used method in evaluative studies which seeks and reports patterns inherent within the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). TA is a method that results in a rich, complex, yet accessible account of the data. TA was chosen as it allowed for an understanding of the data to be developed and patterns within the thoughts and views of participants to be examined. Analysis of the data will be conducted using a realist method to explore “participants’ reality, experiences, and meanings” (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Here, the concept of salience will be used to guide coding that is conceptually and inherently significant, not just frequently occurring. Pictorial data will be discussed by participants during the walks and this data will be analyzed collectively by the research team using TA. Some pictorial data will also be analyzed by focus group participants during their discussions. A qualitative data management software (Nvivo) will be used to facilitate data analysis. Following the analysis of each focus group, a second stage analysis will be conducted to compare and contrast findings across groups. The analysis will seek out consensus, disagreement, and inconsistency within focus groups as well as between green sites. This second stage of analysis will involve discussions within the research team to refine the themes and develop higher-level themes—that is, grouping the open codes into meaningful conceptual categories. This will allow tentative conclusions to be drawn, which may be particularly pertinent for some groups and less important for others. It will also enable conclusions to be drawn regarding overall responses to the use of green spaces, in comparison to more nuanced reactions to specific green sites.

Ethical and regulatory considerations

Assessment and management of risk

As the study involves walking in outdoor environments, the safety of participants and researchers will be a key consideration. Given that our target participant group is parents and caretakers of children, it is likely that participants will bring children with them during the interview. It will be made clear that children will remain under the care of their parents at all times, and the researcher will remind participants that they should feel free to interrupt, or even terminate, the walk to tend to their children when necessary. Walking routes (around 30 minutes) will be planned in advance with participants and potential routes will be reviewed by local community researchers prior to the walk-along interview. A copy of the planned route will be left with the study team. All walks will be conducted during daylight hours and will utilize public paths, pavements, or pedestrian rights of way. We anticipate that most walks will start at a local community venue. However, in some cases the interview may start from a participant’s home address. Walk-along interviews will always be conducted with at least one community researcher accompanying the participant. The walk-along interview will be terminated if at any point either the participant or researcher feel uncomfortable. Researchers will follow the institutional lone working policy and the department Standard Operating Procedures for working alone in the community. It is possible that, during data collection, participants may disclose information to the researcher, or the researcher may have concerns that the individual and/or their children may be experiencing abuse or are at risk of abuse. In such circumstances, the researcher will follow institutional Safeguarding Adults and Safeguarding Children policies. It is unlikely that the walk-along interviews will cover topics that participants find sensitive as they will be focused on aspects of the environment that they like or dislike in their communities. However, participants will be made aware before they start that they do not need to answer any questions that they do not wish to and that they can terminate the interviews at any time. In the event that face-to-face interviews cannot be safely conducted, we will use Zoom to conduct interviews virtually. If face-to-face focus groups cannot be held, we have identified the likes of software Jamboard (from the Google Workspace platform) to enable us to conduct the workshops virtually over the virtual platform Zoom. Tools such as Jamboard enable facilitators to add and pin virtual post-its and have been used to effectively facilitate virtual workshops.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent to participate and be audio-recorded will be obtained from all participants. Data management and storage will be subject to the UK Data Protection Act 1998. Ethical approval for the current study was obtained for the study from the University of York Department of Health Sciences Research Governance Committee (Rec Ref: HSRGC/2021/448/B).

Data protection and participant confidentiality

All information collected will be anonymized and kept strictly confidential, and information will be held securely. The research team will comply with all aspects of the 1998 Data Protection Act, abide by the Caldicott principles, and work within NHS Information Governance requirements. Pictures collected via the PicVoice app, and anonymized quotes from participants may be used in reports and publications arising from this work, including reports which will be used to facilitate the co-design of local improvements. If a participant withdraws consent for their data to be used for the purposes of the study prior to analysis, it will be destroyed. If a participant withdraws consent after analysis has taken place, their data may still be included in the final write-up. The data from this project will be stored for 10 years. The final data set (comprising information from the PicVoice app, walks, and transcripts from the focus groups) will be accessible by authorized members of the research team.

Dissemination

Upon completion of the study, data will be analyzed and a final study report prepared. This will be available on the Born in Bradford website. We will write a lay summary of findings and feed these back to participants using community organizations and community social media channels. We will also send our findings back to our Community Research Advisory Group (CRAG). The group meets on a quarterly basis and will have input into all elements of the research process as the three-year project evolves, guiding improvements to the study process as necessary. We will also ensure infographics and visual representations of our findings are given back to local parent governor groups, friends of groups, and other organizations in the community that use the park. We will do this using our well-established social media platforms, community newsletters, and informal communication channels (e.g., WhatsApp groups) as well as community organization contacts. We will ensure that our findings are also presented back to the community in open dissemination meetings after each of the study stages. We will encourage community members involved in the research to present their own findings during these meetings to indicate their ownership of the outputs. This will include dissemination in multiple languages spoken through trusted translators. Key to our dissemination strategy is presenting visualized findings in mediums such as infographics and posters with minimal text to ensure the findings are more easily digestible for a range of community members who may not understand English. Furthermore, we will display the photographs taken by participants (with their permission) at the dissemination meetings to showcase the work of the community in the participatory process. Detailed recommendations for changes to the green spaces will be presented to stakeholders such as the local council, Better Place volunteers, and the BSB team at the end of the study.

We also plan to write findings up in peer-reviewed publications and present our findings at academic conferences and Better Start Bradford community of practice events (attended by the multiple Better Start Bradford sites) across the UK.

Working with the community

Through the ongoing, reciprocal partnership between BSB and the communities it serves, our findings will be used to empower communities to take ownership of their green spaces. Community members who take part will have a say in the future development and improvements of their green spaces as the study findings will be shared with a range of decision-makers and stakeholders. Those community members who take photographs and consent to these being shown to the wider community and stakeholders will see their contributions displayed for others. Also, community organizations that take part in this study could benefit from new connections and collaborations with other, similar community organizations (for example, from conversations during focus groups), potentially forging community spirit and greater collaborative connections. Families who take part in the photo-voice transect walks will experience time outdoors exploring their green spaces and proposing improvements that, long term, hold the potential to benefit the health and well-being of the entire family if they continue to use the green space. Finally, community members may also benefit from being connected with community organizations by researchers if they express interest in becoming more involved in maintaining, co-designing, and owning their green spaces. BSB will continue to oversee the Better Place project and provide accountability for the changes proposed by the community in this study by continuing to actively work with community organizations to improve the green spaces. Dissemination workshops (discussed above) will ensure that stakeholders, such as the council, are made aware of the needs of the community which arise from the study.

Discussion

Improving engagement with green spaces is a priority to improve physical and mental health (Cronin-de-Chavez et al., 2019; Faculty of Public Health, 2010; R. R. C. McEachan et al., 2016; WHO, 2017) and is increasingly becoming a priority for the UK government (UK Government, 2020). Innovative data collection tools, such as transect walks with photovoice, provide a new and particularly appropriate way of physically exploring local environments and allowing people’s voices about green spaces to be heard. Such methods allow for an exploration of community engagement in the ownership, co-design, and maintenance of green spaces and discovering if this leads to greater use of the green spaces for health benefits (Hatala et al., 2020). Despite this, few studies have employed such methods. It is therefore not clear how community engagement in the ownership, co-design, and maintenance of green spaces can affect the use of green spaces for health benefits (Fors et al., 2015). This study embeds community engagement and a participatory approach with a design tailored to effectively evaluate the ownership, maintenance, and co-design of green spaces and the impact on the use of green spaces to improve health. Our study will provide results that can be used by practitioners to ensure communities are involved with local green spaces and to improve their use and the overall health of communities. It will also bring benefits to the community itself. These benefits are especially important for those vulnerable communities in deprived areas such as Bradford who suffer from higher co-morbidities and the impacts of structural (Denton & Walters, 1999) and social determinants of health (Marmot, 2010, 2020) and for which green spaces are of vital importance.

Limitations

This study is designed to gather community insights on the use of green spaces in four distinct sites in Bradford. The findings from the study are therefore limited by green site location and urban location (the city of Bradford). The current project will reflect the experiences and views of community members in Bradford only. Other green sites or cities could reveal differing interpretations of engagement with green space. We acknowledge that there are multiple competing realities and perspectives that may differ across time and context, and the analysis findings will be limited to the time and context of this study. The transferability of our findings is nonetheless maximized by the inclusion of multiple stakeholder perspectives (members of community organizations and local families) and enabled by the community advisory groups and networks. Interpretation of the feedback will consider potential limitations regarding the generalizability of the findings. Future research may include both broader location investigations (multiple cities) and encapsulate expertise by experience of communities in different countries.

Conclusion

This study will use feedback from community members and families, themselves experts by experience, to use innovative methods to co-produce recommendations for the improvement of green spaces in a deprived and under-researched urban area to maximize health benefits. Our data aims to explore how community ownership, co-design, and maintenance of green space affect the use of UGS for health benefits. The deliverables of this study will be recommendations for improvements to the development and long-term ownership, maintenance, and co-design of green spaces by communities in Bradford so that they can bring about maximum health benefits. This innovative qualitative approach has not been previously employed in urban areas to evaluate the impact of ownership, maintenance, and co-design by communities on the use of UGS for health benefits. Our vision is that this approach will become a routine feature of evaluating community involvement in UGS to improve mental and physical health as it strongly advocates consultation and collaboration with the community using participatory methods throughout. Such methods are particularly vital to allow community voices to be heard in underserved or multi-ethnic communities which are vulnerable due to the social and structural determinants of health and for whom green spaces play a vital role in mental and physical health.