The Need for Community-Led Public Health Solutions

Despite trillions of dollars in healthcare spending, the achievement of population health outcomes in the US has stagnated, and inequities in well-being continue to persist (Tikkanen & Abrams, 2020). Solutions to these problems cannot come only from healthcare, but require collaboration across multiple sectors (e.g. social services, criminal justice, education, economic development) with an explicit and intentional focus on equity and justice (Wolff et al., 2016).

In their call to action to embrace a new approach to public health, dubbed Public Health 3.0, DeSalvo et al. (2017) describe the future role of public health leaders as strategists who can lead cross-sector collaborative efforts to address root causes of poor health, well-being and equity outcomes. This requires the focus of public health efforts to shift from being community-placed (i.e. situated in communities but with services owned and delivered in a fragmented manner by public health agencies and healthcare institutions) to being community-based (i.e. development and planning of integrated transformational solutions led by diverse community coalitions focused on local priorities, local context and local innovation). As the country struggles to overcome and build from COVID-19, the need for these approaches have even greater urgency.

This shift to community-based efforts focused on systems change increases the complexity of planning, implementation, and evaluation in two ways. First, community-led solutions will need to be “change packages” that have multiple interacting components at various levels of the socio-ecological model (Craig et al., 2006). Second, the settings in which these packages are implemented are complex and heterogeneous, with the path between solutions and outcomes subject to context-dependent characteristics, non-linear feedback loops and emergent, unpredictable behavior (Lipsitz, 2012). Therefore, the development and implementation of community-based change actions cannot simply be mechanical replications of generic evidence-based interventions but must utilize an approach referred to by Greenhalgh & Papoutsi (2018) as “complexity-informed.”

Complexity-informed Implementation and Evaluation

A complexity-informed approach recognizes that successful implementation in a complex system requires an appreciation for how interactions between multiple community-specific influencers affect outcomes and the development of processes that are responsive to unanticipated and emergent consequences that might arise. This requires the ability to test solutions through a series of sequential experiments, to evaluate how the system responds and making any context-appropriate adaptations based on the findings. In an article about decision-making in complex systems, Snowden & Boone (2007) describes this approach as “probe-sense-respond”, which uses small tests (probes) led by communities to “sense” the system before any response can be formulated.

A complexity-informed approach to program implementation also needs appropriate evaluation methods that allow learning from iterative cycles of experimentation and action to support implementation. These methods should also contribute to understanding of common processes and pathways through which communities bring about change, and enhance knowledge over time about processes that are community-specific and those that are more broadly generalizable. At the same time, these methods should promote the leadership of those closest to the data in interpretation, nurture relationships between and across communities, and accommodate changes in data, evaluation team membership and context as the initiatives evolve.

The data required for complexity-informed evaluation are different from those collected for traditional outcome focused research evaluations. As noted by DeSalvo et al. (2017), there is need for granular, actionable data that provide rich qualitative and quantitative information about the process of implementation. It is enormously resource intensive to create systems to collect this data. Much of the data available for evaluation, therefore, are likely to be routine project implementation data collected opportunistically in the field. These data are often incomplete and are referred to in the literature as Flawed, Uncertain, Proximate, and Sparse (FUPS) (Wolpert & Rutter, 2018). Evaluation methods will need to incorporate collaborative synthesis of FUPS data collected from multiple sources.

Focus of Paper

The goal of this paper is to describe a systematic approach for practical community-led evaluation using multi-source, imperfect real-world data that we used to evaluate a real-life, community-based system transformation initiative called Spreading Community Accelerators through Learning and Evaluation (SCALE). We present the details of our approach, and what we have learned about doing complexity-informed evaluation in multi-community field settings. We have used some results from the evaluation to illustrate the outputs of the various steps of our evaluation process, but we do not present the detailed analysis of the results from SCALE on the implications for community transformation. Our goal in this paper is to demonstrate how our new approach can be applied by individual communities seeking to gain insights about their own processes of change, or by multiple communities engaging in joint meaning making.

Context – The SCALE Initiative

SCALE Overview

SCALE was a multi-year Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funded national initiative to build the capacity of community coalitions to achieve long-term improvements in community health, well-being, and equity. The initiative was a signature initiative of the broader 100 Million Healthier Lives (100MLives) movement and was led by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), the industry leader in the use of Quality Improvement (QI) methods to achieve better outcomes in health and healthcare. SCALE was implemented based on an active partnership between the implementation team (IHI, partners, and faculty), and community coalitions selected through an application process.

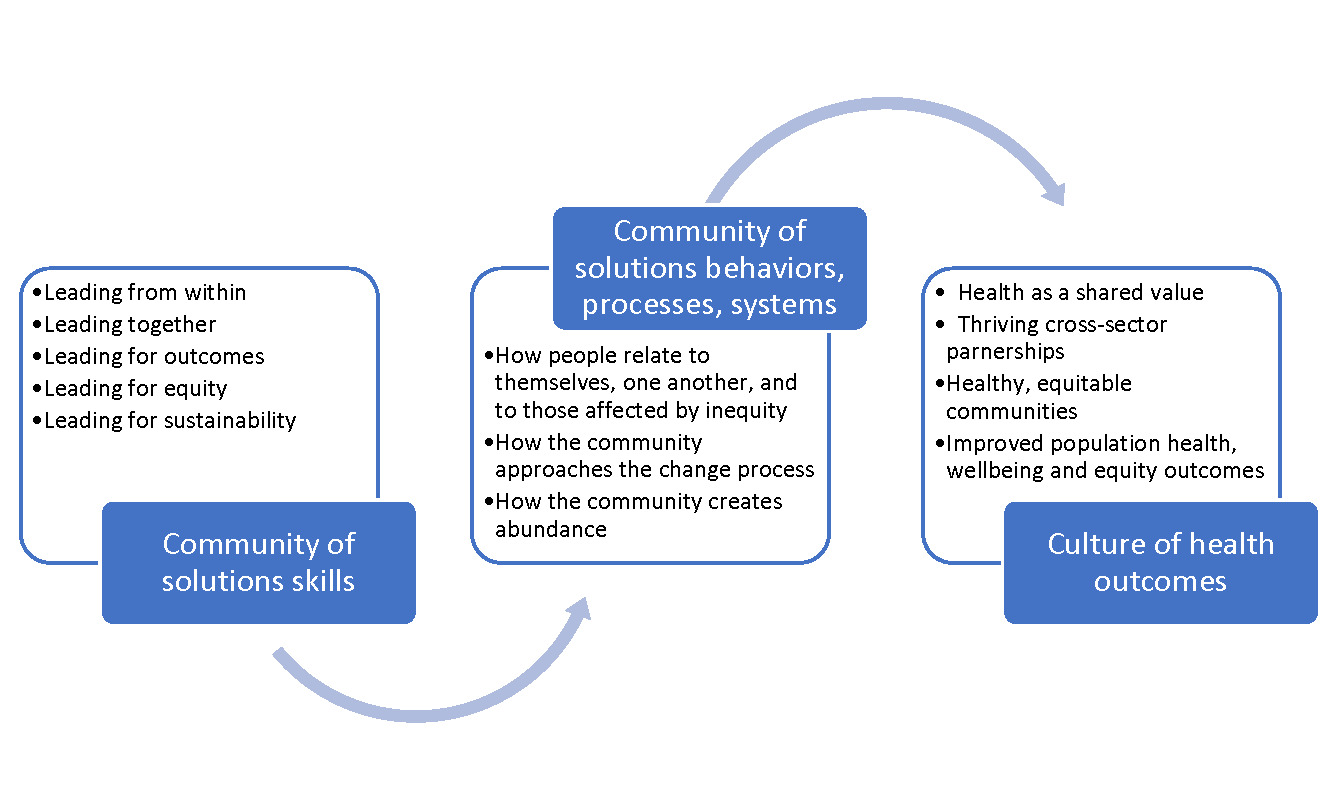

SCALE Theory of Change

The SCALE theory of change is shown in Figure 1 (Network for Improvement & Innovation in College Health, n.d.). The theory links the achievement of healthy, equitable communities to the acquisition and everyday practice of a core set of skills, strategies, and tools known collectively as the “Community of Solutions Framework.” These included skills in personal leadership, in developing deep and lasting intra- and intercommunity relationships and in the use of systematic QI methods. The theory of change posits that when these skills are acquired and become part of everyday practice, the way in which members of community coalitions relate to each other begins to shift and an environment is created where communities can effectively engage in complexity informed improvement to find innovative and lasting solutions to their health and wellbeing challenges.

SCALE Communities

Twenty-two diverse community coalitions nationwide were selected through a competitive process to participate in SCALE from 2015-2019. Each community coalition had a “tripod” leadership structure, made up of formal leaders engaged in improving the community (e.g., business leaders, public health leaders, agency leaders, health care leaders), community connectors (people who served in a natural facilitator and connector role), and community residents with lived experience (community champions). Integrating community residents with lived experience into their core community improvement teams as partners and leaders was an integral component of the SCALE theory of change.

Community improvement initiatives undertaken by these coalitions spanned a wide range of topics including food security, adverse childhood events, safe neighborhoods, building youth leadership, women’s mental health, racism, and equity. The communities were trained in the Community of Solutions Framework through eight multi-day face-to-face events called CHILAs (Community Health Improvement Leadership Academies) and were assigned coaches to help them apply these skills to their individual improvement initiatives. In the later stages of SCALE, which included 18 communities, the coalitions were required to spread these skills to other communities within the region.

An evaluation team consisting of faculty and graduate students from the Universities of North and South Carolina was embedded within SCALE. At the end of the project, the evaluation team facilitated a collaborative effort to learn about the process of community transformation across SCALE, using the data collected by the communities during the implementation process. Since there was no off-the-shelf evaluation approach that could be used, the evaluation team, in partnership with IHI and the community coalitions, created the novel approach described in this paper adapting a combination of two existing qualitative research methods: meta-ethnography and participatory action synthesis for use by practitioners.

Methods

Evaluation Questions

Evaluation questions were developed through an iterative collaborative process involving the funder, IHI, and select community members who volunteered to participate in the evaluation. Questions were solicited online, sorted and streamlined by the evaluation team and sent back for the next iteration. Multiple cycles of online feedback were used to craft a final set of overarching questions important to all stakeholders. They were:

-

What are the most common pathways that communities have followed in their transformation journey?

-

What are the common and unique knowledge, capabilities, practices, and relationships that the communities have used?

-

What are the mechanisms that have brought about change?

Evaluation Theory

As mentioned above, our evaluation approach is a new method involving an amalgam of meta-ethnography and participatory action synthesis. Meta-ethnography, pioneered by Noblit & Hare (1988), is a structured seven-step method for synthesizing findings from a small number of ethnographic studies to create new interpretations. The primary focus is to use convergent and oppositional themes across the studies to craft higher-level interpretations that reveal new levels of meaning linking the studies. Meta-ethnography is part of a set of interpretive methodologies called qualitative research synthesis (Major & Savin-Baden, 2010) that expand the approach to qualitative studies beyond just ethnography. Overall, these approaches seek to create higher order meaning by synthesizing the learning from lower-level data.

Participatory action synthesis (Wimpenny & Savin-Baden, 2012) arose in response to critique that interpretive methods such as meta-synthesis are limited in their ability to construct new knowledge because they do not utilize the contextual experience of researchers to bring new and creative interpretations beyond what is present in the data. Participatory action synthesis adopts a social constructivist lens to the meaning making process, and explicitly acknowledges the need to ground the data within the contexts and values of the settings in which the data were collected. It recognizes synthesis as a communal process where the stakeholders bring their own social, political, and cultural experiences to the table. Additionally, it posits that these experiences could result in the collective creation of new interpretations of the data that offer greater insights than what can be achieved through a passive process of identifying convergent and divergent themes. During the synthesis process, each participant brings his or her own personal worldview or research locus to the data, and a team interpretation is negotiated through open discussion of the intersecting narratives emerging from these worldviews. Iterative cycles of joint meaning making and integration of new themes with the data deepens the collaborative process.

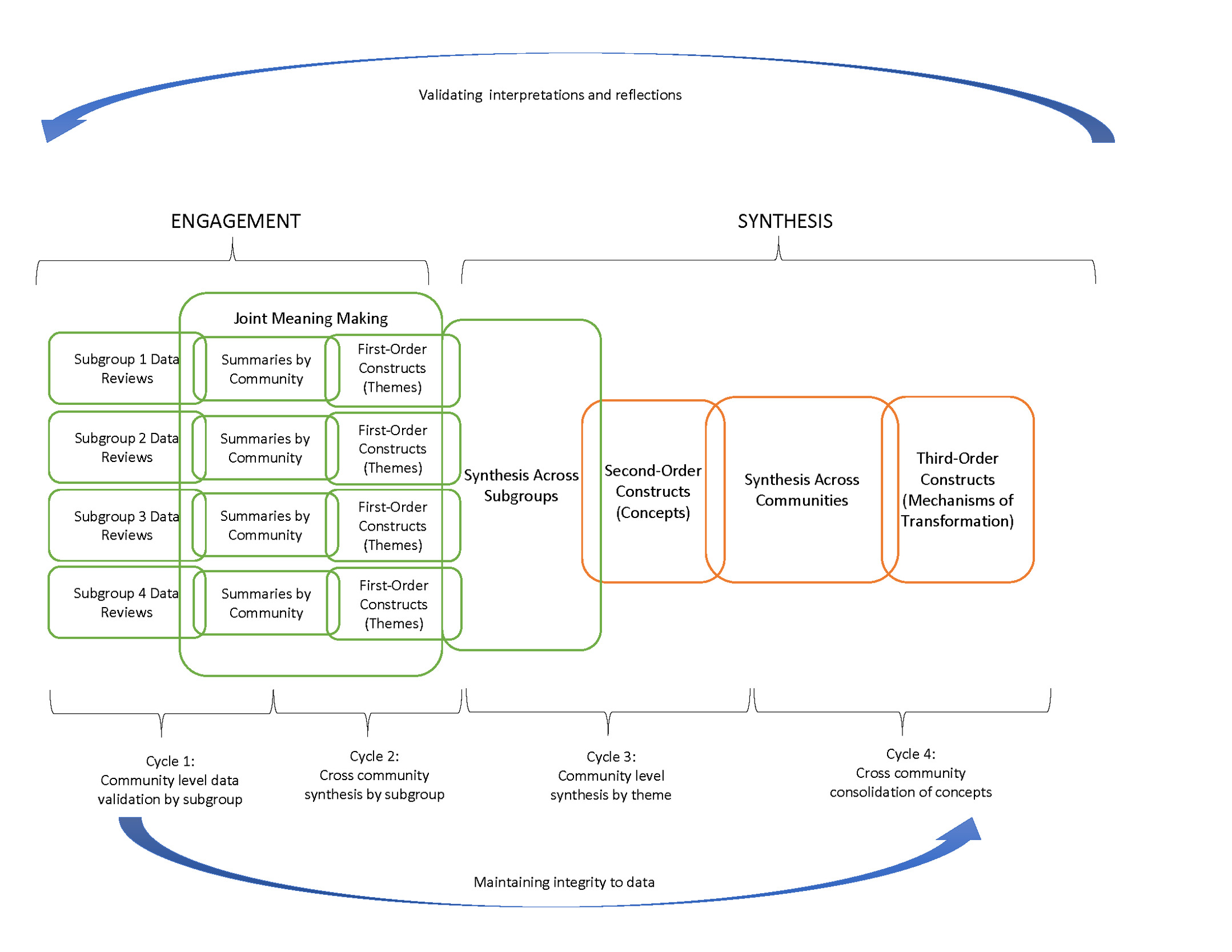

Both meta-ethnography and participatory action synthesis were developed as research methods, and the guidelines for their use are targeted at researchers (Dixon-Woods et al., 2005). For researchers, the epistemological and ontological underpinnings of these synthesis methods are important because they determine the participants and the types of data that should be included to answer a particular research question. In their introduction to participatory action synthesis, Wimpenny & Savin-Baden (2012) require the data to be to be situated within an established qualitative research theory, and caution against poor quality data. Moreover, they emphasize the importance of the explicit articulation of each team member’s research position (i.e. the “reflexive stance” of an individual, which is intrinsically tied with the team member’s role), so that the negotiation about what to include and exclude in the communal interpretations can be equitable and transparent. To adapt these two methods for use in practice settings, we relaxed some of the theoretical constraints mentioned above (e.g. the need for established research theory, and the requirement of high-quality data), but remained faithful to the key principles underlying these methods: communal meaning making, valuing contextual experience, encouraging open discussion and negotiation, and systematic integration of data from multiple sources. Specifically, we used the iterative reflection action cycles of the participatory action synthesis process to engage key SCALE stakeholders in reflecting on, validating and interpreting community specific data. We then used the steps of the meta-ethnography approach to create progressively higher order concepts and themes, and to develop lines of argument about the process of community transformation. Figure 2 shows our hybrid approach that integrates the two methods.

Evaluation participants

There were three key stakeholder groups who participated in the evaluation. Implementation team stakeholders included IHI staff and coaches responsible for developing SCALE training and tools and supporting community coalitions on their use. Community stakeholders were members of the community coalition teams involved in SCALE, and typically one of the members of the “tripod” described earlier. Evaluation team stakeholders planned and facilitated the synthesis sessions.

Evaluation data sources

Data used for the evaluation fell into two main categories: routine data on the progress of SCALE activities, and data collected by the evaluation team. Descriptions of the available data sources and the SCALE activities they aligned with are shown in Table 1. While each community coalition had outcomes they were seeking to improve, the primary objective of SCALE was to strengthen the capability of communities to engage in the change process, and the goal of the evaluation was to gain knowledge about the processes of change. Therefore, the data used for the evaluation was process data collected as the SCALE coalitions worked on their change projects. They included documentation of how the coalitions used the improvement tools and relationship building skills that were taught in the learning academies, ongoing results from the use of these tools, challenges faced by the coalitions in the implementation of their projects, and how they addressed these challenges.

Evaluation Approach

Our evaluation approach shown in Figure 2 has two key components: (a) an engagement component that enables SCALE stakeholders to bring their knowledge and perspectives to fill data gaps and to provide community specific interpretations of their data and (b) a synthesis component that aggregated these insights into common themes and concepts relevant across communities. We used two cycles of engagement involving representatives from all communities, followed by two cycles of synthesis and interpretation with a smaller team of evaluation team members with input from select community representatives. All interpretations made by smaller groups were validated back with the communities and used to update the results.

Engagement Cycles

Cycle 1: Community level data validation by subgroup: The objective of the first cycle was to use community input to improve the quality of implementation data and fill data gaps. To engage community coalition stakeholders in their areas of interest, four subgroups were created, each focusing on one key aspect of the SCALE Theory of Change: Community of Solutions skills, Quality Improvement methods, Spreading and Scaling-up Practices, and Engaging People with Lived Experience. Coalition members were invited to participate in any subgroup they chose, and participation in the process as a whole was voluntary. Each subgroup met virtually for 90 minutes biweekly for 26 weeks, facilitated by an evaluation team member.

Cycle 2: Cross community aggregation by subgroup: During the second cycle, the subgroup structure was continued to encourage the engagement of community members who were already involved. The teams reviewed the data from the first cycle to identify common ideas that emerged across the communities for each subgroup. In the bi-weekly meetings, these ideas were discussed among all stakeholders, integrity to the source data was assured and refinements were made as necessary.

Synthesis Cycles

Cycle 3: Community specific synthesis: The subgroup structure adopted for the first two cycles required a significant investment of community and evaluation team time, since four separate meetings needed to be conducted every week. For the next two cycles, a synthesis team was formed, consisting of community stakeholders who were available and willing to spend the time and implementation and evaluation team members. Led by the evaluation team, this team interpreted the subgroup data from Cycle 2 in the specific context of each community. Evaluation team members set up calls with members from communities who did not participate in this cycle to validate and fine tune these interpretations.

Cycle 4: Cross community synthesis: The fourth cycle of synthesis was conducted entirely by the evaluation team. This was focused on integrating the community specific data from Cycle 3 into common cross-community processes that were adopted by all communities in their transformation efforts. Detailed definitions were created for each process.

Results

The evaluation involved data from four topical subgroups and 18 communities. Since this paper focuses on the evaluation approach and not the results of the evaluation, for illustrative purposes we have selected data from two communities and one subgroup (Engaging People with Lived Experience) to show the outputs from the first three cycles of our process. These are presented in Table 3. A summary of the outputs of each cycle is presented in Table 2.

Cycle 1 Outputs

The outputs from the first cycle were data summaries of the raw data of each community with assessments of data quality and identification of data gaps. These summaries were iteratively updated in the subgroup meetings as the communities provided additional details to close data gaps. In Table 3 we show raw data from three sources for our two sample communities: (a) the project management system where program goals are set and progress is measured; (b) transcripts from community calls with their coaches; and (c) an interview with the implementation team during a routine project milestone call. The descriptive summaries describe the essence of this data pertaining to the engagement of people with lived experience. For example, the data from the project management system summarizes how this is done in Community A: the community has people with lived experience in their coalition; includes people with lived experience throughout the planning process; and has utilized input from people with lived experience to guide strategic direction of park network and partnership.

Cycle 2 Outputs

The outputs from the second cycle involved the review of data summaries to identify themes representing common ideas across communities for each subgroup topic. A set of themes was generated for each topical sub-group at the end of Cycle 2. Table 3 shows the themes used by many communities for engaging people with lived experience:

-

Using recruitment strategies for intentional targeting of community champions

-

Ensuring that people with lived experience, including community champions, co-design intervention with the community coalition

-

Soliciting feedback in an effort to engage the community and better understand their wants/needs

-

Growing leadership of people with lived experience, including community champions, by training them as new leaders, and providing professional development and/or mentorship opportunities

-

Engaging and involving youth/adolescents as people with lived experience in their work

Cycle 3 Outputs

The outputs of this cycle contextualized the relevant themes and subgroup topics from Cycle 2 for each community and created concepts that describe how each community applied the themes to its setting. For example, Table 3 shows that, from among the themes of engaging peoples with lived experience shown above, Community A uses theme 2 (engaging PLE early to co-design solutions). Community B uses theme 5 (integrating youth with lived experience into the community’s transformation work as leaders). For each community, the concept is the aggregate picture of the community-specific instantiation of each subgroup theme.

Cycle 4 Output

The output of this cycle was a list of overarching concepts that combine the community-level concepts from Cycle 3 into elements common to most communities’ change processes. The overarching concepts and their definitions are shown in Table 4. For example, one overarching concept is the need for authentic dialog within and between communities engaged in SCALE. These are defined as space for, and ability to have difficult or sensitive conversations. Different communities might have different approaches to creating these spaces, but the need for an enabling environment for sensitive conversation emerged as an important driver of capacity for community change.

Discussion

Contribution to the literature

We believe that our approach is one of the few practical examples of how to conduct complexity informed evaluation, which is a critical need as public health initiatives increasingly focus on equity and well being rather than on narrowly defined health outcomes. Greenhalgh & Papoutsi (2018) identify five characteristics of complexity informed research: (i) generating insights rather than establishing a “truth”; (ii) illustrating a plurality of voices instead of a single authoritative voice; (iii) focusing on contribution and influence rather than on effect size; (iv) making decisions based on imperfect or contested data and (v) acknowledging multiple interacting influences on the outcome. There is little guidance in the literature about how they can be operationalized for use by practitioners. By being grounded in established qualitative research methodology, our approach has robust theoretical roots, but by enabling the approach to be used by those who are closest to the data, we provide the ability for practitioners to gain insights from program data that are contextually relevant and immediately usable. Evaluation expertise largely sits among researchers, and our approach makes it accessible to practitioners while still maintaining a systematic and rigorous process.

Key learning and recommendations

We share our learning from the SCALE evaluation to inform future evaluators and implementers who might want to use this approach in their own settings.

1) Emphasize relationships and trust building: “Evaluation” is a loaded word and even if it is clearly established that the objective of the collaboration is for joint learning about what works, the emphasis on the need for rigorous validation of the data and a systematic process of synthesis can be experienced as judgmental by some community stakeholders. In the SCALE evaluation, the evaluation team began working with the communities in an implementation support role (Scott et al., 2020) and built personal relationships with community stakeholders. Even then, a lot of careful planning and preparation went into both the design and the execution of the evaluation process to ensure that the communities felt assured that the locus of the evaluation was centered around the communities’ ownership and knowledge of their data.

For example, in our evaluation approach, the first two cycles were primarily used for data review and for identifying common themes across communities. Community specific interpretations that required communities to think critically about their implementation processes were only undertaken in the third cycle. By this which time most stakeholders had enough opportunity to participate in the evaluation and feel comfortable that their voices would be welcomed and respected.

2) Involve community members in planning and design of the evaluation: Each cycle was preceded by communication sessions to explain the goals for the cycle, and community members were encouraged to provide suggestions about the methodology. Each bi-weekly synthesis meeting began with an update of progress to enable members who had not attended previous meetings to be caught up. All templates used for synthesis were created collaboratively, were extensively tested with community and implementation stakeholders and were editable by everyone irrespective of whether they participated in the evaluation meetings.

3) Be realistic about roles and time commitments: Recognizing the wide variation in evaluation expertise across the stakeholder groups, roles for community members were clearly established and agreed upon so that each team member could bring his or her own unique knowledge into the synthesis process. Stakeholders were informed of the time commitment needed in advance, but competing priorities made it difficult for several of them to continue in the group meetings, necessitating follow-up conversations that consumed additional time and resources. Overall, the evaluation team significantly underestimated the time and labor required to manage the synthesis cycles to assure adequate data quality, community input and overall engagement.

4) Build capability for data collection and use early in the implementation process: Our evaluation approach is designed to piece together disparate project implementation data, but poor data quality can be a significant impediment. All SCALE communities were guided by a common theory of change and were provided standardized tools for routine data collection to support their improvement work. However, these tools were perceived to be burdensome and not relevant by some communities to their improvement projects resulting in data gaps. Empowerment evaluation (Wandersman et al., 2005) approaches that build the capacity for communities to develop systems for routine data collection relevant to their change efforts, and encourage the use this data for ongoing synthesis and learning should be an integral part of the evaluation design.

Conclusions

One aspect of the plan of action under the Healthy People 2030 framework, approved by the Department of Health and Human Services in 2018, is to provide accurate, timely and accessible data to enable action to address regions with poor health or at high risk. Another aspect is to provide tools to the public and other stakeholders to evaluate progress related to the achievement of health and wellbeing. Data and tools are a good start, but are inanimate without people embedded in communities who have the ability to collaboratively gain insights from the data about how to improve. This requires processes for systematic data analysis and for bringing diverse community members together to enrich the analysis with contextual interpretations so that both community specific and generalizable change ideas can be created. In this paper, we have described an innovative evaluation methodology that achieves both these aims by blending two qualitative research methods: participatory action synthesis and meta-ethnography and adapting them for use in practice. This methodology has promise for learning how to advance the aims of large-scale health and well-being initiatives domestically and globally. Researchers and practitioners interested in using this approach should be willing to take the time and put in the effort, should be clear and transparent about the process, should assign roles to all stakeholders to encourage participation and shared ownership, and should co-design and test data synthesis tools prior to implementation.

List of Abbreviations

100MLives: 100 Million Healthier Lives

CHILA: Community Health Improvement Leadership Academies

FUPS: Flawed, Uncertain, Proximate, and Sparse

IHI: Institute for Healthcare Improvement

PLE: People with Lived Experience

QI: Quality Improvement

SCALE: Spreading Community Accelerators through Learning and Evaluation

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable

Consent for publication: Not applicable

Availability of data and materials: Available from the corresponding author on request.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding: This study was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) [grant numbers 74438, 76406]. RWJF had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing and preparing the manuscript.

Authors contributions: KR led the synthesis of data, developed initial drafts and readied manuscript for publication. TC, RSR, JC, BSC, and PH were involved in data collection and contributed to the synthesis of data. CEC assisted in data synthesis. RR developed evaluation design, led data synthesis, developed the manuscript structure, and revised manuscript drafts. All authors reviewed, provided comments, and approved final manuscript.

Acknowledgements: Not applicable