Introduction

Sexual violence prevention participatory researchers have commonly engaged youth and young adults in their research (Beatriz et al., 2018). Given the high rate at which high school and college students experience victimization (Fisher et al., 2009; Harland, 2015), there are many benefits to engaging youth in the participatory research process. However, reflective first- and second-person action research approaches can provide deeper insights into young researchers’ backgrounds with rape culture. Arts-based research can be especially evocative when working with youth. To that end, the goal of this report is to highlight the value of second-person arts-based research for existing action research teams and action research with youth.

Second-person action research allows young adults involved in ongoing participatory action research projects to reflect upon their personal experiences with rape culture. It also allows them to better understand the roots of the problems and how they learned and formed attitudes about it. This brief report outlines the processes involved in a two-phase, second-person arts-based action research project exploring the experience of young sexual violence prevention action researchers with rape culture throughout girlhood and young womanhood. This project was centered around collaboration and equal partnership between two undergraduate college students and a PhD research mentor. The process of second-person arts-based action research into sexual violence prevention, and partnering with young adult researchers, is a transformative experience that subverts the hierarchical traditional research power structure. Instead, it allows youth to share power with established researchers and frame the research as a conversation.

Arts-Based Research

The foundations of arts-based research (ABR) have the potential for transformative collaboration and change among marginalized communities. Due to the accessibility of art, art-based research has the power to promote open dialogue, self-reflection, and understanding (Leavy & Hastings, 2010). In a study conducted with Central and Eastern European (CCE) female migrant tourism workers, the use of arts-based research empowered the women to gain new skill sets in addition to developing creative thinking skills (Rydzik et al., 2013). Rather than focusing on the dominant preconceptions towards CCE workers, the collaboration with the CCE female migrant workers shifted researchers’ focus to experiences significant to the individual themes addressed within the participants’ artwork (Rydzik et al., 2013). Likewise, the use of arts-based research has the capacity to decolonize research processes and focuses to instead provide transformative opportunities for both researchers and collaborators. While many college students are agents of change, many are overlooked or viewed solely as research subjects rather than collaborators. However, a study regarding feminist research on sexual assault prevention highlights the benefits of including college students as co-researchers and collaborators in order to fully understand the campus climate of sexual assault (Krause et al., 2017).

Collaboration is crucial in order to fully understand issues that affect communities and specific populations. In a study centered on empowerment through ABR methods, The Life Story Mandala method was used to generate data on the major life events and trauma of participants. This resulted in self-realization as well as healing and reconciliation for collaborators (Miettinen et al., 2019). Overall, ABR can provide opportunities of collaboration, growth, and greater data generation than the use of limited or traditional methods of research.

Second-Person Action Research

Second-person action research, also known as second-person research, must be understood in the framework of first-, second-, and third-person research. Torbert (2006) defines first-person research as self-study, second-person research as conversation, and third-person research as shared leadership in community-based inquiry which goes beyond the members of a research team, thus distinguishing it from second-person research. The majority of action research projects fall under Torbert’s definition of second-person research. To that end, Torbert (2006) also notes that each of these processes build upon each other, such that second-person research is not possible without first-person research. Bradbury & Reason (2006) also characterize second-person research as “collaborative inquiry” that has grown from “tentative beginning to full cooperation,” (p. 345) to address “issues of mutual concern” (p. xxvi) for group members. Marshall (2016) adopts definitions of first-, second-, and third-person action similar to Torbert (2006), with the added emphasis on mutual engagement among those involved in second-person research. Coghlan & Brannick (2014) elaborate that through second-person research practices of collaboration and codevelopment, “actionable knowledge for a third person audience emerges,” (p. 7). Chandler & Torbert (2003) offer the most comprehensive view of second-person action research, defining both the second-person voices and second-person practices, both mirroring the conversational nature of the definition as seen in Torbert’s (2006) work. Second-person research differs from traditional interview research in that in second-person research, all involved are co-researchers, engaged in collaborative inquiry through conversation, rather than the traditional researcher/interviewee dichotomy. Unlike autoethnography, which is a first-person method, second-person research takes place in the process of conversation, blurring the distinctions between data generation and analysis.

Context

The research team was composed of one mentor researcher and two undergraduate student researchers. All three members of the research team were involved in ongoing participatory research projects around sexual violence prevention before starting this art-based research project. One student was co-researcher on a project exploring what high school sexual violence prevention program alumni wanted their teachers to know about sexual violence. The other student was working on a qualitative project examining students’ responses to a prevention curriculum. The connections between the two projects and the shared mentor led to the research team starting a discussion on general themes of sexual violence, which then led to reflection on their own personal experiences. This discussion led us to reflect upon how all members of the research team were uniquely qualified to engage in self-study of our backgrounds with rape culture activism and research because all three of us had the experience of undergraduate anti-rape activism and research.

Through first-person and second-person research, the team used art to examine personal experiences of rape culture and its effect on girlhood. Each week, the research team created art in response to prompts regarding rape culture from girlhood to womanhood. The team then discussed the art to understand the artist’s intent, as well as any observed recurring thematic elements. The team also created dialogue surrounding the effects of rape culture in both personal life and through societal gender standards. Within this framework, the team assessed the meaning of girlhood, what changes occur to enter womanhood, and how the effects and influence of rape culture progress during the transition from girlhood to womanhood. Creating art allowed the team to share vulnerable experiences of personal encounters with rape culture that may not have been expressed directly in conversation, such as fear and defense mechanisms used to “prevent” rape. Overall, art-based expression proved to be a crucial mechanism in the reflection and processing of how rape culture has permeated the broader culture, as the creative element allowed individuals to grasp concepts and traumatic events that may have been difficult to solely verbalize.

Methods

Phase I

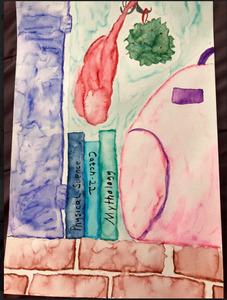

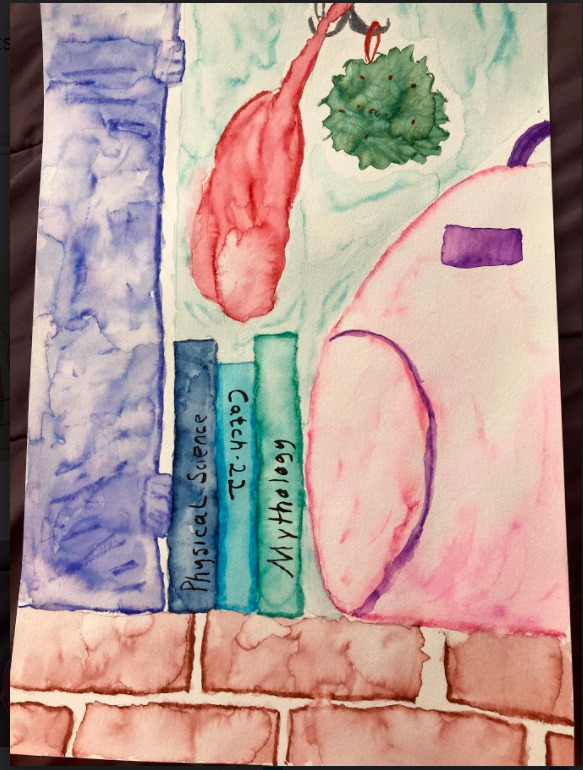

In the first stages of the project, the research team created five prompts around experiences of girlhood and rape culture. The first phase of the project spanned five weeks. During each week, each research team member created their own art in response to the prompt. At the end of the week, the team met virtually to share their own art and comment on others’ artwork. After responding, group discussions examined themes and differences in the art as well as its ties to girlhood and rape culture. Figure 1 shows an example art piece from the project. Throughout this process, participants considered not only the art, but also the discussions they generated, which were recorded for future reference as project data.

Following the completion of phase one artmaking, the research team reviewed group discussions to identify the emerging topics as part of the reflection process. Each team member wrote a letter to the internal voice of rape culture to reflect on the themes from the first phase and what they learned during the art sharing process. To begin phase two, the group decided the next topics based on what they had explored.

Phase II

During the second phase of research, the team focused on individual projects that sought to explore unique topics within rape culture. As a result of the research team’s differing areas of focus, the discussion process was modified to approach each subject. Individual discussions became longer in order to describe the art making process, the area of focus, how the artistic medium used supported the project, and what thoughts about rape culture emerged. As a result of this new discussion process, group reflections regarding individual projects became shorter and were instead replaced with dialogue regarding what the research team learned.

Throughout the second phase of reflection, the team analyzed projects for thematic connections across the duration of the project. The team noted themes that were apparent among all three projects. As the team continued to speak about the effects of rape culture on girlhood and womanhood in depth, the group turned to a discussion regarding what the appropriate next steps would be to share this information more widely. Possible applications discussed included arts-based prevention curricula for high school students or a book-length project. Further research has been on a temporary hiatus due to both student researchers’ undergraduate studies during the academic year.

Lessons Learned

Art as a Transformative Methodology for Introspective Research

This approach is innovative in that it blends second-person research with artistic approaches. The artistic approaches allowed us to reflect deeply, represent our personal thoughts, and have rich conversations that pushed our ideas further than either self-reflection or discussion prompts alone. The artistic element of this study deepened our reflective process and enabled us to better communicate our understanding of rape culture, as well as going into more depth beyond the conventional understanding of rape culture. Research teams can use artistic second-person research processes to spur reflection and in-depth group discussion, particularly with difficult subjects such as sexual violence and rape culture.

Power of Interaction in Second-Person Research

Our approach layered the introspective nature of first-person research or self-study with the richness of in-depth conversations. Second-person research is not merely adding multiple perspectives to first-person research with multiple perspectives. The interactive nature of the second-person study enriches the research process and allows topics to emerge organically. The research team envisioned this process as data generation rather than data collection because it went beyond gathering information and instead generated new knowledge together. Similarly, research teams can co-create knowledge through data generation using similar processes.

Organic Flexibility in Second-Person Research

The multiple cycles undergone in this study were flexible and reflective of what lessons from the process. Initially, we did not intend for the study to go beyond five weeks. However, the depth of conversations indicated that there was more in store for the project than a single cycle. The flexibility of second-person research can allow research teams to follow inquiry cycles as it meets their needs.

Shifting Power Dynamics

The processes described in this paper shifted the power dynamics away from the traditional researcher/participant dichotomy to co-researchers of equal standing. In using this approach, the research team was able to share mutual ownership of the research process and engage as team members of equal standing within the project. We shared responsibility of all stages of the process, from design to data generation, analysis, and coauthorship. Because all team members were making art and reflecting on their experience, an environment of trust emerged. Research teams seeking to build an environment of equal standing can use this process to create a group climate of openness.

Conclusion

This project illustrates the power of second-person action research as a process for participatory research teams, subverting the traditional research structure and allowing for truly equal partnership between undergraduate and established researchers. The emphasis on the group interaction in these second-person processes creates a bridge between individual reflection to community action, building from first- to third-person as Torbert (2006) outlines. Intrinsic to our second-person arts-based design is first-person reflection, and the process both enhances our existing third-person research efforts and offers direction for future third-person research projects as well. Using second-person research allows a working group to step back and gain a better understanding of members’ own relationships with the problems they are researching. Additionally, the arts-based nature of this project helps to build the first- and second-person elements of this project by facilitating reflection in the first-person stage and deep discussion at the second-person stage.

In this study, our approach was uniquely tailored to sexual violence research because it enabled us to understand our personal background with rape culture and to contextualize it within the wider social structure. Participatory groups can use these processes to build team relationships or to reflect on future directions for community-based projects. They also have the potential for the reflection stage and collaboration with community members. For example, in a community-based sexual violence prevention program, participants could engage in modified second-person arts-based activities to reflect upon the formation of their own beliefs about sexual violence. In sharing our methods, we hope to offer a tool for other community-based action research groups to integrate second-person research.