1. INTRODUCTION

Persons experiencing poverty have not always participated in research destined to understand, explain, and influence their situation. Indeed, while the multidimensionality of poverty may have been acknowledged in the early days of modern scientific inquiry into the subject, the voices of those living in poverty were famously excluded from initial data collection processes. In 1886, Charles Booth began mapping poverty in London using census statistics, data from employers, local school boards officials, policemen, charity workers and clergy who were in contact with persons experiencing poverty and could report on their situations, as well as from observations made by field researchers based in settlement houses (O’Connor, 2016). Two decades later, Seebohm Rowntree noted that his researchers were “often able to assess poverty on the basis of ‘external evidence’ of the multiple observable facets of poverty, making ‘verbal evidence superfluous’” (Rowntree, 1908, as cited in Bray et al., 2020, p. 2). Later, in Rowntree’s study in York, a questionnaire survey including questions on income and household budgets was administered to 11,560 families. The approaches followed by Booth and Rowntree represented a “turning point in the history of poverty research” by viewing poverty as a “subject for empirical measurement rather than more explicitly moral or abstract political economic inquiry” (O’Connor, 2016, p. 170). For over a century, and particularly in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, the practice of gathering data on poverty through questionnaire surveys and using the concept of income poverty remained methodologically hegemonic (Chambers, 2007).

The inclusion of persons with the direct experience of poverty in research in a participatory way began in earnest with movements such as action research and community-based participatory research (CBPR), inspired by thinkers such as Paolo Freire and Orlando Fals Borda. As noted by Pain & Francis (2003), “the defining characteristic of participatory research is not so much the methods and techniques employed, but the degree of engagement of participants within and beyond the research encounter” (p. 46) Therefore, involving persons experiencing poverty in research for purposes beyond data collection, “as a process by which communities can work towards change” (Pain & Francis, 2003, p. 46), represented a turn in the way persons experiencing poverty were viewed in the research process. They were no longer seen merely as objects of research, but subjects who were able to reflect, act upon those reflections, and have the potential for being conscious of their situation in society (Freire, 1970). In the field of international development, Rapid Rural Appraisals (RRAs) and Participatory Rural Appraisals (PRAs) were designed by non-governmental organizations in the 1980s in response to growing criticism of traditional methods such as surveys and field visits (Chambers, 2007). Drawing on Freirian philosophy and participatory tools borrowed from adult education, the PRAs sought to include the knowledge and experience of people in poverty, and to actively involve them in the planning and management of development programs.

In 1992, the World Bank introduced “participatory poverty assessments” (PPAs), which, like PRAs, marked a shift from the traditional way of collecting information about persons in poverty as objects of inquiry. PPAs seek to “understand the experience and causes of poverty from the perspective of the poor themselves,” similar to anthropological approaches (Robb, 2002). Using participatory research methods, PPAs aim to complement poverty assessments that use income and consumption indicators, education levels, and health status to determine levels of poverty in order to view the poor as experts of their own situation (Robb, 2002), capable of analyzing and addressing the issues relevant to the causes and conditions of poverty. Robb (2002) notes a steady growth in the World Bank’s use of PPA in assessing poverty in the mid-to-late 1990s: increasing from one-fifth of poverty assessments in 1994 to half in 1998. By that year, 43 PPAs had been completed by the World Bank, mainly in the developing world: 28 in Africa, 6 in Latin America, 5 in Eastern Europe, and 4 in Asia.

This brief overview of the emergence of participatory poverty research shows a growing interest of researchers and policymakers for incorporating the “voices of the poor” in research that concerns them. In this article, we compare two international studies on poverty—one conducted in 1999 by the World Bank and published in 2000 as “Voices of the Poor: Crying out for Change”; the other, conducted from 2016 to 2020 as a partnership between the University of Oxford and the international movement ATD Fourth World, titled “The Hidden Dimensions of Poverty.” After outlining our theoretical background (Section 2), we discuss the methodological tools and processes deployed in the studies (Section 3). In Section 4, we focus specifically on the extent to which the studies empowered participants at each stage of the research process, fostered agency through the cultivation of alliances of pro-poor groups, recognized and countered power dynamics, and achieved transformative results. In Section 5, we widen the discussion to broader issues concerning the participation of persons experiencing poverty in poverty research, including the role of the facilitator, the time taken to conduct each study and the effect of participation on injustices in knowledge systems. We conclude and reflect on our findings in Section 6.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND : PARTICIPATION, BETWEEN TOKENISM AND TRANSDISCIPLINARITY

In recent years, sustainability science and transdisciplinary research have emerged as approaches that are concerned with “real world” sustainability problems, which are complex, value-laden, or contentious, and often involve nature-society interactions (Global Sustainable Development Report, 2019). These approaches are characterized by the inclusion of actors outside of academia such as citizens, NGOs, private actors, policymakers, and other members of civil society as partners of the research process. Such new(er) epistemological currents have led to a revival of the debates surrounding participation of poor or marginalized groups in research, and the relationship between academic and non-academic researchers and their respective roles in the research process (see e.g. Barnaud & Van Paassen, 2013; Conde, 2014; Godrie et al., 2020; Marshall et al., 2018).

The distinction proposed by Godrie (2017) is useful to disentangle three levels of participation: consultation, collaboration, and control. At the level of consultation, the views of stakeholders are collected and there is no guarantee of how these views are taken into account in the research. This level closely resembles extractive research approaches (Wilmsen, 2008), of which common methodological tools include surveys, interviews and participatory observation. The person surveyed or observed—the interviewee—retains no control over how and whether their views or inputs will be used in research. In collaborative participation, stakeholders are involved in various steps of the research process, particularly in the initial phases; however, they are less frequently involved in data analysis or interpretation, or in the diffusion of results. This is the case with most projects of Citizen Science. Finally, when stakeholders participate with control, the research is both initiated and led by the stakeholders independently or in collaboration with researchers (Godrie, 2017). In our view, the latter two categories of participation, i.e. collaborative participation and control, both correspond to two transdisciplinary forms of research, which Elzinga (2007) distinguishes from token participation.

Similarly to the levels of participation proposed by Godrie (2017), the Spectrum of Community Engagement serves as a useful heuristic for assessing the degree of participation in community research projects. On the spectrum, six stances and their respective impacts on the researched community are identified. In the first stance, the community is ignored and there is no participation. The impact on the community is that it becomes (or remains) marginalized in the process. In the second stance, the community is informed about the process, but not meaningfully involved; the result is placation. The third stance is about consultation: input from the community is gathered but this ressembles token participation, since participants have no control over how the information gathered is used. In the fourth stance, the community becomes involved. At this stage, the community needs and assets are integrated into the process. Examples include community fora and interactive workshops. In the fifth stance, collaboration is ensured, with the community playing a leadership role in the implementation of decisions. Finally, in the sixth and final stance, the community takes ownership of the project and its participation is fostered through community-driven decision-making. Table 1 summarizes the Movement Strategy’s stances and juxtaposes these with Godrie’s levels of participation.

A key difference between transdisciplinarity and token participation is that while the former leads to the empowerment of participants, the latter (token participation) “involves would-be participants going through the motions of being consulted without really having any bearing on the problem definition, analysis or ultimate implementation of the results” (Elzinga, 2007, p. 357). In a similar vein, Marshall et al. (2018) note that if transdisciplinary research is to be transformative:

The role of the researcher is not only to facilitate knowledge production about a problem and how it might be solved, but to do so in such a way that a space is opened for poor and pro-poor groups to exercise greater (potentially transformative) agency and to reshape the arenas of knowledge systems. (p. 4)

According to Marshall et al. (2018), cultivating alliances to enable transformative space-making and revealing power dynamics help to support such transformations.

In this paper, we analyze two international studies on poverty with respect to the above-mentioned criteria. First, to distinguish between token participation and authentic collaboration, we examine the extent to which participants—and in particular the persons experiencing poverty—were involved in all phases of the research, and the degree to which they were empowered in the process. We focus specifically on whether power and decision-making were shared in the definition of the research questions, the analysis and the synthesis of data, as well as the publication and presentation of results. Second, we explore whether alliances of persons experiencing poverty and pro-poor groups were cultivated. Third, we assess whether the two studies recognized and challenged power relations that exist between participants, and between participants and researchers. Finally, we seek to evaluate whether the research projects produced transformative results that allow for the reversal of injustices in knowledge systems.

Table 2 summarises the elements of participatory research that are analysed for both cases.

Through taking together the literature on transdisciplinary research and participation, we argue that for research to achieve transformative results, participants must be empowered throughout the process. By ensuring participants retain control of the different phases of the research, by developing alliances and by revealing power dynamics, transdisciplinary research has the potential to overcome structural injustices in knowledge systems by producing new insights that serve disadvantaged communities instead of merely extracting knowledge from them. Along with Marshall et al. (2018), we consider transformational results as those which “challenge dominant narratives and agendas and subvert the structures of the incumbent knowledge system”(p. 3). After presenting each of the studies according to Lang et al.'s (2012) phases (Section 3), we assess the two research projects against the criteria developed by Marshall et al. (2018) as summarized in Table 2 (Section 4).

3. TWO LANDMARK STUDIES: “VOICES OF THE POOR” AND “HIDDEN DIMENSIONS OF POVERTY”

According to the methodological guide for the “Voices of the Poor,” the purpose of the consultations was to “enable a wide range of poor people in diverse countries and conditions to share their views” in order to “inform and contribute to the concepts and content of the [World Development Report] 2000/01,” which served as “an opportunity to revisit the World Bank’s poverty reduction strategy in light of recent development experience and future prospects” (Poverty Group et al., 1999, p. 2). In “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” the objective was to “refine the understanding and measurement of poverty” in order for the research to “contribute to more sensitive policy design at national and international level and thereby to the eradication of poverty” (Bray et al., 2019, p. 6).

While both studies were international in scope, the sample size of countries studied and the number of persons involved diverge considerably. The “Voices of the Poor” study was conducted in 23 countries and involved more than 20,000 persons experiencing poverty. The fieldwork for the research project was completed within three months. On the other hand, the “Hidden Dimension of Poverty” study was carried out in six countries and involved 1,091 individuals, including 665 men, women, and children with the experience of poverty, 262 practitioners and 164 academics. The project took more than two years of fieldwork to complete. The two studies thus followed drastically different approaches in seeking to produce data of high validity. In “Voices of the Poor,” the external validity of the study was, to a certain extent at least, guaranteed due to the large sample size (more than 20,000 persons answering the questions) and the wide range of countries selected across the globe (although only in the Global South and former USSR). On the other hand, the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” ensured internal coherence and external validity as a result of the process: where “knowledge is identified, brought forth and refined in a careful and deliberative democratic process within small working groups” (Godinot & Walker, 2020, p. 270). Moreover, this knowledge was triangulated, verified, and enriched through iterative loops. Finally, the inclusion of countries both in the Global North and the Global South ensured that the findings of the study could be generalized to other countries in both contexts.

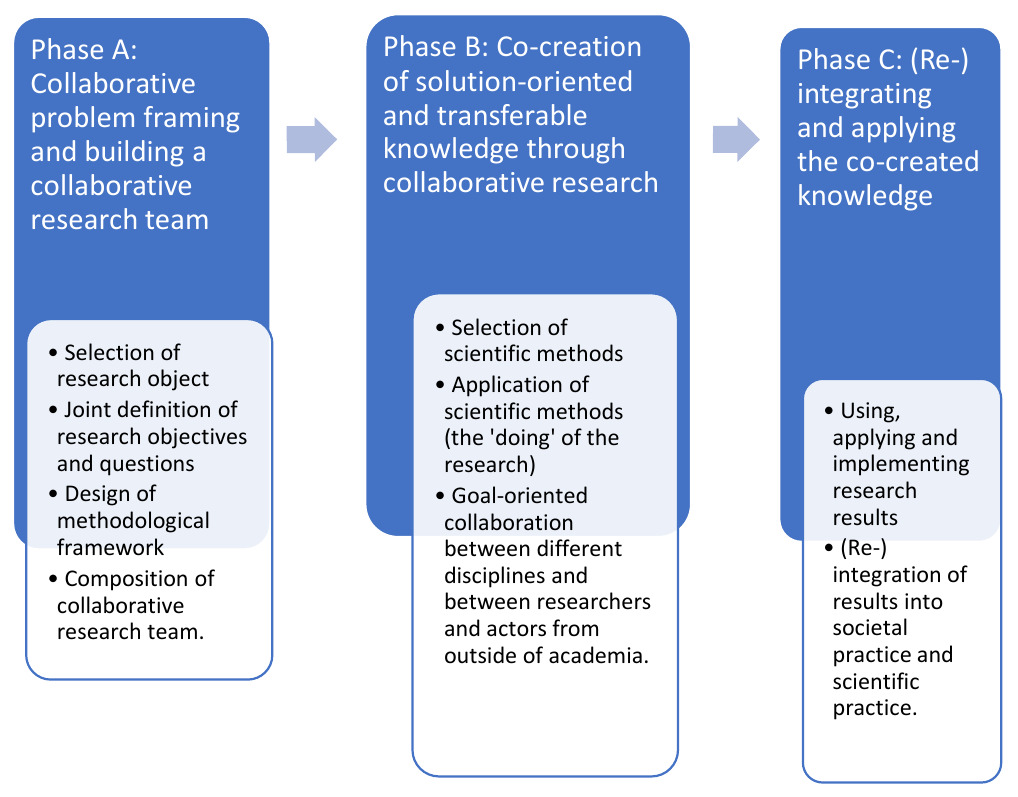

In this section, we describe the steps followed in each study, distinguishing between three phases, based on the work of Lang et al. (2012), which provides an overview of the phases of an ideal-typical transdisciplinary research project: the first phase consists of collaboratively framing the research problem and building the collaborative research team; the second phase seeks to co-create knowledge through collaborative research; the third and final phase reintegrates and applies the knowledge into the societal sphere. Figure 1 illustrates the three phases identified by Lang et al. (2012).

3.1. Processes and methodological tools

3.1.1. Phase A: Collaborative problem framing and building a collaborative research team

The consultations which took place in the framework of the “Voices of the Poor” study were intended to constitute the backbone of the World Development Report 2000/01: Attacking Poverty, which was perceived by the World Bank as an “opportunity to revisit [its] poverty reduction strategy in light of recent development experience and future prospects,” (Poverty Group et al., 1999, p. 2) among others, by developing multi-dimensional indicators of well-being and measuring the standard of living below and above the household level. The “Voices of the Poor” study on the whole consisted of both primary research conducted through the consultations in 23 countries and reviews of existing Participatory Poverty Assessments (PPA). Upon its completion it became recognized as “one of the most widely discussed pieces of development research ever” (Cornwall & Fujita, 2012, p. 1751). The results were published in a three-part report. The second report, “Voices of the Poor: Crying out for Change”, which was elaborated in a participatory way, is analysed in this paper. It explored four main thematic areas related to poverty: well-being and ill-being, priorities of the poor, the role of institutions in the lives of the poor, and gender relations in households and communities. The study is the largest Participatory Poverty Assessment (PPA) conducted to date. It was deployed in 23 countries and involved more than 20,000 persons experiencing poverty in approximately 272 communities. The research project began with two methodological workshops in late 1998, a pilot-testing of the methodology in four countries, and the drafting of the methodological guide (Chambers, 2002). Following this, the research teams were composed, trained, and prepared for conducting fieldwork. A sample of 23 countries was selected, according to criteria of “interest, willingness and capacity” (Chambers, 2002). The following countries were selected: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Jamaica, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Nigeria, Somaliland, Zambia, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Uzbekistan.

Nearly two decades after the “Voices of the Poor” research, the international study “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” co-piloted by Oxford University and ATD Fourth World began in reaction to the definition of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in 2015. Following the criticism and ulterior evaluation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the successor of the millennial global agenda for development—also known as Agenda 2030—was developed in a more participatory way. This was in line with the Guiding Principles on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 2012, which call for the participation of people experiencing poverty in the development of poverty measures. The first of the SDGs, “No Poverty,” calls for the end of poverty “in all its forms everywhere.” The first target for this objective calls on countries to eradicate extreme poverty, measured using the threshold of $1.25 per day (increased to $1.90 in 2015). The second target seeks to reduce by one half “the proportion of men, women, and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions”—without specifying what these are. The project thus sought to fill this gap by working together with persons experiencing poverty to identify the dimensions of poverty.

The approach used in the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” study by ATD Fourth World and the University of Oxford is known as Merging of Knowledge, a research approach developed by the international movement ATD Fourth World in the 1990s. It explicitly aims to eradicate poverty through the inclusion of persons experiencing poverty in the research design, alongside practitioners and academics. Through the use of deliberative techniques such as break-out sessions in peer groups and reporting back to mixed plenary sessions using spokespersons, the Merging of Knowledge seeks to alter existing power relations between participants in order to allow knowledge from each of the three sources (experiential, action-based and theoretical) to be constructed and “merged” to obtain a more complete picture of poverty, its causes, and its consequences. The Merging of Knowledge guidelines are included in Annex B to this paper.

The “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” research applied the principles of the Merging of Knowledge approach internationally on a large scale. This meant that all participants had to adhere to the principles that “change is necessary”; that “each and every person possesses knowledge” which should be merged to “produce a knowledge that is more complete and more in keeping with reality”; that “nobody should be left on their own,” i.e. that a secure framework should be put in place so that people experiencing poverty; professionals and academics have the chance to “reflect, express themselves and discuss” their knowledge; and finally, that “each and every person is part of the research team,” i.e. that “each and every participant something to offer to every aspect of the research” (ATD Fourth World, n.d.).

The study consisted of several iterative loops. The first step of research included building the conceptual basis for the study, as well as an international coordinating team composed of researchers from the University of Oxford and permanent volunteers of the ATD Fourth World movement. During this initial phase, the methodology was selected, as well as the partners for the study and the countries in which it was to be conducted: Bangladesh, Bolivia, France, Tanzania, the UK, and USA. The selection was made to ensure that the sample included three countries in the Global North and three in the Global South. Further, a team of researchers had to be willing to cooperate with an organization on the ground in each of the countries; in five of these, the organization was ATD Fourth World, while in Bangladesh, it was a partner organization called Mati. The next step in this phase involved constructing the six National Research Teams (NRTs) for each country involved. This step was undertaken in 2016 for four of the six countries and slightly later for the two remaining NRTs. These national teams were composed of four to six persons with a previous or ongoing experience of poverty, two to four academics and practitioners, and two facilitators or coordinators, and were involved in planning, coordinating, and implementing each of the research phases. The NRT meetings were highly participatory, with deliberative discussions held to arrive at consensus, or agreement reached by consent, where applicable.

After their creation, the NRTs used outreach techniques to identify and recruit participants who would be involved in the ulterior phases of research. Between 13 and 38 peer groups were established in each country in various locations. These were composed of adults and children living in poverty, practitioners working alongside people living in poverty, and academics. In some countries, such as Tanzania, the participants were financially compensated for their time and input. In other countries, such as France, financial remuneration was not possible due to the stringent controls imposed on beneficiaries of social security and the risks associated (i.e. the possibility of losing benefits through the participation in remunerated work). However, in all countries, the costs of participation were covered by the research project.

Table 3 lists the countries in which the studies were conducted (with countries included in both research projects indicated in bold).

3.1.2. Phase B: Co-creation of knowledge through collaborative research

3.1.2.1. National level

In the “Voices of the Poor” research, the qualitative and participatory fieldwork was conducted over a period of three months. Researchers received a set of guidelines and questions to ask, defined in the methodological guide. Moreover, the document provided guidance to researchers about how to ask questions and the methodological tools to be used (e.g. focus groups, participatory ranking and scoring, causal-impact analysis, individual in-depth interviews, etc.). While allowing some open-ended questions to be asked, in some cases it also required study teams to ask specific questions around pre-determined categories in order to enhance comparability between sites and countries. For example, the guide suggests using focus group discussions to explore ideas related to well-being and ill-being. While allowing for various issues (risk, security, vulnerability, opportunity, social and economic mobility, social exclusion, social cohesion, crime and conflict) to emerge from the discussion, the guide also notes that if they are not introduced in the focus group discussion, the facilitators should mention them, as well as mentioning that “a clear distinction must be maintained between issues and terminology used by the people and that introduced by the facilitators” (Annex A, p. 24). The document continues with a set list of sub-questions to be asked. For instance, regarding social cohesion, the guide asks facilitators to explore “How do people define social cohesion?”

Despite the risk of imposing preset categories on persons experiencing poverty, Robert Chambers notes:

That said, the researchers’ site reports from the communities are a remarkable read. The straitjackets of academic theory, jargon and categories are little in evidence. The reports come over as faithful in reporting the realities and values that poor people presented. They manifest an honesty and vivid realism that shines through and carries conviction. (Chambers, 2002, p. 142)

The data collected was analyzed, synthesized, and aggregated into site reports, then into country reports.

In the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” data was collected through an extensive process in each of the six countries. The following steps were followed by each NRT: First, members of the NRTs facilitated different peer groups (composed of either persons experiencing poverty, practitioners or academics) repeatedly to identify the characteristics of poverty and to begin the construction of relevant dimensions. Various tools were used, and NRTs had “considerable autonomy” in “choosing techniques to facilitate dialogue on poverty within the peer groups” (Bray et al., 2020, p. 4). For instance, in France, the peer groups met four to five times, applying various tools, methods, and techniques to identify an initial set of characteristics of poverty. These tools included an introductory coat of arms exercise, a body mapping method to reflect on links between poverty and the body, as well as various exercises enabling participants to establish a hierarchy between the dimensions of poverty identified. Each peer group prepared their own reports based on the findings. The tools used in this data collection process were participatory in the sense that all peer groups were involved in the application of the methodological tools. In other words, persons experiencing poverty, professionals, and academics each produced a coat of arms and each worked on the body mapping exercice. This contributed to placing each of the peer groups on an equal footing, rather than asking the persons experiencing poverty alone to participate in the exercises using the tools (and having professionals or academics facilitate the process, for example).

Second, the NRTs worked on merging dimensions identified by each of the peer groups in the following way: persons with the experience of poverty in the NRT synthesized the findings from the reports of peer groups composed of persons experiencing poverty; practitioners in the NRT synthesized the findings from the reports of peer groups composed of practitioners, and academics did the same from the reports of their respective peer groups. According to instructions followed by the NRTs, dimensions could be renamed, or new dimensions created, but no characteristics of poverty identified in previous steps could be eliminated in the peer group syntheses.

Lastly, these separate synthesis reports were merged into a single national set of dimensions for the country by the NRT. For example, the subsequent process was followed in France. First, the representatives of each peer group within the NRT presented the list of dimensions developed by the persons with their “source of knowledge” (experiential, action-based or theoretical) to the other two groups. Next, each peer group was asked to consider the following three question: 1) “Within the findings of the other peer groups, what advances or shifts my groups’ own knowledge?”; 2) “What are the nodes or knots to be discussed?”; 3) “What dimensions are missing?” Based on the answers to these questions, the NRT arrived at a list of dimensions for France. Finally, the report was presented back to the original peer groups during a Merging of Knowledge session of two to three days for discussion. A multitude of meetings were organized to interpret the outcomes and draft a national report, including the new insights from the peer groups who had been consulted for a second round. Across the six countries, approximately 70 dimensions of poverty were identified.

3.1.2.2. International level

Both studies also produced an international report, synthesizing the findings of the research conducted at national levels. In the “Voices of the Poor,” once the country reports were finalized, an international synthesis workshop was held near New Delhi in June 1999. Attended by the study leaders of each participating country, it included verbal presentations by country group leaders, the collection of insights and points on specific subjects on cards, meetings to discuss information harvested, card sorting to enable the emergence of categories, and subject groups to gather information (Chambers, 2002). Collecting points were used in different rooms corresponding to the four themes of the consultations: exploring well-being, problems and priorities of the poor, institutional analysis, and gender relations (Annex A). A separate space was maintained for reflections and contributions that did not match these themes (Chambers, 2002). The final book was co-written by four members of the research teams who were present at the international synthesis workshop.

In the Hidden Dimensions of Poverty, representatives from NRTs (including persons experiencing poverty) from the six countries met to discuss the outcomes of the work conducted on the national level. The findings from the three countries of the Global North and three countries of the Global South were initially discussed separately; thereafter, the two groups came together to agree on dimensions applicable in all six countries. The final list of nine dimensions and five modifying factors was then sent to the NRTs for discussion (the NRTs and local peer groups could react to these, providing their remarks and expressing their disagreement where applicable). After a period of iterative editing, the international report was prepared in three languages in time for a presentation held at the OECD in May 2019. The final international report was completed in July 2019.

3.1.3. Phase C: (Re-)Integrating and applying the co-created knowledge

The knowledge resulting from “Voices of the Poor” was published as 21 national synthesis reports, a global synthesis, and later a more cohesive analysis and synthesis published as “Voices of the Poor: Crying Out for Change” (Chambers, 2002). The World Development Report 2000 was intended to draw upon the findings of the “Voices of the Poor,” however, some doubts remain among the policy analysts concerning the actual influence of the consultations on the final report (see Chambers, 2000, “Were the ‘Voices of the Poor’ really heard?”). Nonetheless, the “Voices of the Poor” has had considerable impact in the policy field, notably serving as the basis for assessing the consequences of ecosystem change on humans in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment.

In the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” this final phase of the research is arguably still underway. As noted by Godinot & Walker (2020), the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” could be understood as either participative policymaking or participative research. However, to the extent that it is research-oriented rather than directly commissioned by government agencies, “the results will need to be effectively ‘marketed’ to the policy community” (p. 271). Indeed, the objective of the study is not merely to produce scientific knowledge, seeking to go further in order to “contribute to more sensitive policy design at national and international level,” and ultimately aim for “the eradication of poverty” (Bray et al., 2019, p. 6). One way in which the co-created knowledge is being re-integrated into the scientific and societal spheres is through cooperation with the INSEE (the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies), which has used the results of the research to design questions to be added to standard surveys concerning the measurement of poverty in collaboration with ATD Fourth World and the study participants. These questions have been designed to collect data on the institutional mistreatment experienced by persons experiencing poverty, which constitutes one of the dimensions identified by research. The OECD has also planned to create a working group to reflect on the research results and to integrate them into the policy design and planning of the institution.

Table 4 summarises the phases of the research projects, according to the steps developed by Lang et al. (2012).

4. RESULTS OF ASSESSING THE PARTICIPATORY PROCESS DIMENSIONS

As discussed in Section 2, non-extractive research that has the potential to overcome structural injustices in knowledge systems must empower participants (Elzinga, 2007; Wilmsen, 2008), providing disadvantaged participants with control over the research process. Moreover, Marshall et al. (2018) note the importance of cultivating alliances and revealing power dynamics throughout the process. In this section, we assess the extent to which the process features of two recent participatory studies on multidimensional poverty: 1) empowered participants; 2) cultivated alliances of pro-poor groups; 3) revealed power dynamics throughout the process; and 4) resulted in transformative knowledge about poverty.

4.1. Empowering persons experiencing poverty in the research process

As the first evaluation criterion, we understand empowerment as a process embedded in the research design and examine the extent to which power was shared throughout the study between the researcher and the researched. This includes the power to formulate the research questions and frame the problem field, the power to analyze and synthesize the data, and the power to publish and present results. Empowerment can also be understood as an outcome, such as an improvement in stakeholders’ capacity to act upon their own situation (Wilmsen, 2008). However, for the two studies that are the object of this paper, we lack the necessary data to study empowerment as an outcome.

While the “Voices of the Poor” approached persons living in poverty with the intention of conducting a consultation, the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” sought to counter power imbalances and create the conditions for knowledge co-production between persons experiencing poverty, practitioners, and academic researchers. More specifically, while analysts in the “Voices of the Poor” retained the power to define the research questions, analyze and synthesize data, as well as publish research results, this power was shared more equitably in the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty.” This gap is related to the difference in the ways the study teams were constituted. The methodological guide for the “Voices of the Poor” study stipulates that the country study team should “consist of at least three sub-teams of four members each” (1999, p. 43), paying attention to gender balance and knowledge of local languages. While the guide does not specify the academic or professional background of the members of the research teams, it does indicate that it should be ensured that “all the team members are adequately trained in the required field methodology” and that they “have prior experience with using PRA methodology” (1999). We assume, therefore, that most of the members of the country study teams were researchers, analysts, or other professionals, but not persons experiencing poverty themselves.

The “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” study followed an altogether different approach. Study teams were highly heterogeneous and included academics, persons with the experience of poverty, and practitioners. They were facilitated by a coordinating team composed of permanent volunteers of ATD Fourth World, an academic researcher and a research assistant. The number of total members ranged from eight (in Bolivia) to nineteen (in the United Kingdom) in each of the six countries studied. The specific composition of NRTs in this study ensured that one or more representatives of each peer group was included at all phases of the research. Moreover, following the principles of transdisciplinarity and equality (see Section 2 above), it ensured a parity between the types of knowledge at all stages of the research: knowledge gained from life experience of people experiencing poverty; knowledge gained by professionals who serve the most deprived people and academic knowledge which is indispensable and yet remains “partial, indirect and purely informative” (Godinot & Walker, 2020, p. 269). As a result, the study team ensured the equal involvement for all co-researchers, regardless of background. The academics or researchers did not, as in the “Voices of the Poor,” take the leading roles in conducting the study (asking questions, analyzing data, drafting reports). In other words, “Merging of Knowledge affords equal status to each group of knowledge-holders (rather than considering some as ‘experts’) and brings representatives from all groups together in a debate towards achieving consensus” (Bray et al., 2020, p. 4).

4.1.1. The power to define the research questions

In the “Voices of the Poor”, the methodology guide provided a list of specific issues to be addressed, which one critique qualifies as “pre-framed categories and circumscribed questions” (Cornwall & Fujita, 2012, p. 1754). Indeed, the document provides a range of prompts, pre-defined questions, and categories to be asked to the respondents.

By contrast, the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” research process followed an entirely inductive approach, allowing the dimensions of poverty to be identified and to emerge from open-ended exercises such as body mapping or photovoice (ATD Fourth World, n.d.; Bray et al., 2020). These two distinct approaches gave a different role to the study teams. While in “Voices of the Poor,” researchers held a certain power to define the research questions, determine the extent to which the process was “open or closed” (Chambers, 2002), guide the discussions, and introduce specific concepts, in “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” the study teams rather served as facilitators within the participatory process.

4.1.2. The power to analyze and synthesize data

The “Voices of the Poor” research conferred significant power to the study teams for analyzing the data collected during the on-site visits. Indeed, while the questions posed to respondents requested participants analyze certain aspects (for example by ranking problems and priorities, or to identify trends over time), the study teams were responsible for analyzing and aggregating the data at site and country level. According to Robert Chambers, who participated in the study as an analyst:

The findings presented daunting problems of analysis and difficult decisions about trade-offs and the construction of knowledge by the analysts. There were issues over selection of evidence, quotations taken out of context, and the processes through which categories emerged, challenging the reflexivity of the analysts and qualifying the representativeness of some of the data presented. (Chambers, 2007, p. 26)

By contrast and as mentioned above, in the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” data analysis and synthesis were carried out using feedback loops which enabled participants of the various peer groups to have an overview of the findings produced by the NRTs, to provide their feedback and mark their (dis)agreement. As such, “people in poverty are not therefore the objects of research, they participate fully to generate and analyze research findings on more than equal terms with other stakeholders” (Godinot & Walker, 2020). Additionally, the immediate confrontation of three types of knowledge (academic, practical, and experiential) at the point of data collection meant that the analysis was conducted collectively. According to Godinot and Walker:

(…) bringing together the different forms of knowledge, academic and practitioner (and, insofar as possible, policy and lay knowledge), with that gained from direct experience means that disagreement and confrontation is almost inevitable as misunderstanding and misrepresentation are revealed. Unlike data drawn for surveys or even deliberative polling, the evidence is examined and analyzed at the point of collection rather than later, at a distance from the field. The analysis is therefore responsive and investigative, targeted on resolving inconsistencies while seeking evidenced explanations and justifications that are carried forward in support of the findings. There should be no need, therefore, to speculate on meaning, post facto, as is the norm in statistical analysis, since each finding has a narrative history and derivation. (2020, p. 9)

4.1.3. The power to publish results

In the “Voices of the Poor” project, as in most research, the study’s authors (i.e. the World Bank and its analysts) maintained control over the publication process and the development of outputs. Thus, in addition to drafting and publishing the report “Voices of the Poor: Crying Out for Change,” the World Bank used the findings from the site and country reports to inform the World Development Report 2000/2001. By contrast, in the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” “the knowledge, products and outputs generated in the Merging of Knowledge process are deemed to be owned by those people that generate them and can only be shared by consent and with acknowledgement” (Godinot & Walker, 2020). By giving the peer groups and heterogeneous NRTs the power and control over the research results, the risk of “ventriloquizing” the poor, i.e. taking citations out of context and using them for means other than what they intended, was reduced (Cornwall & Fujita, 2012).

4.2. Cultivating alliances between poor and pro-poor actors

According to Marshall et al. (2018), alliances of poor and pro-poor actors within the transdisciplinary study team are crucial to enabling transformative space-making through transdisciplinary research. Engaging with diverse actors at different levels of decision-making, they argue, is likely to build the legitimacy of subaltern knowledges and to enable change at different scales. Such alliances may include actors such as communities of the poor collaborating with researchers, local NGOs or community-based organizations (CBOs), wider social movements, local government officials and national NGOs (Marshall et al., 2018). Both the “Voices of the Poor” and “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” cultivated such alliances, though to a more narrow extent than as defined by Marshall et al. In the former, the methodological guide encourages research teams to link the fieldwork to existing projects conducted by the World Bank, its donors, and partners. For example, in Vietnam, the study was implemented with the cooperation of the World Bank, donors, local and international NGOs, and local and national government representatives (Adan et al., 2002). However, such partnerships varied in breadth and strength; indeed, in other countries where the study was deployed (e.g. Ethiopia), alliances were weaker due to insufficient time (Adan et al., 2002).

In the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” alliances were also a central feature of the operationalization of the study. The partnership between ATD Fourth World and Oxford University served as a basis for the research project across the six countries. For each specific country, different alliances were forged. For example, in France, ATD Fourth World partnered with the Secours Catholique, Caritas France, the Association des Centres Socio-Culturels des 3 cites in Poitiers and the Institut Catholique de Paris. Additional partnerships were created to constitute the peer groups in rural and urban settings, and, notably, an international scientific committee composed of members of the OECD, the World Bank, and other organizations was created. However, it is worth pointing out that the peer groups involved persons experiencing poverty, professionals working alongside them, and academics, but not policy makers or government officials. Involving policy makers or representatives of local and national governments may have improved the “possibility for direct influence” of the results and insights obtained in the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” (Marshall et al., 2018, p. 10).

4.3. Revealing power relations

Structural injustices in knowledge systems are largely due to the power relations that exist within those systems (Marshall et al., 2018). As a result, there is a need to reveal the power dynamics at play and the ways in which “power impacts on the creation and use of knowledge for particular objectives” (Marshall et al., 2018, p. 6). By revealing power dynamics, these can be countered through the use of various tools and methods, such as intentional facilitation in working groups.

The methodological guide for the “Voices of the Poor” study contains little, if any, references to power relations and dynamics that may be present in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. In some country studies, it is clear that these were taken into account. In Ethiopia, care was taken to avoid the inclusion of officials in the collection of information, in case they would influence the process and discussions (Adan et al., 2002). However, this particular point was not explicitly nor systematically considered in the methodology.

In the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” power relations are explicitly acknowledged and countered in the Merging of Knowledge methodology (see Section 5 below). Indeed, for the three peer groups to actively collaborate on equal footing, a number of measures are taken (e.g. facilitation mode, use of peer groups, methodological tools, etc.), and this is the basis of the Merging of Knowledge research approach. Therefore, while power relations may have been revealed and countered ad hoc in the “Voices of the Poor” depending on the study team and country, this feature is at the very core of the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty.”

4.4. Achieving transformative results

While a complete analysis of the results of both studies is beyond the scope of this article, in this section we briefly compare one section of “Voices of the Poor” with the findings of the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty.” Although the findings of the former are more far-reaching and broader in scope than the latter, there is one chapter (of seven) of the “Voices of the Poor: Can Anyone Hear Us?” report which can be directly compared to the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty”: the chapter on well-being and ill-being in the latter recognizes the multidimensionality of these concepts, and finds resonance in the more recent conclusions of the ATD/Oxford study. Following the Millenium Ecosystem Assessment—a 2005 synthesis report which analyses the state of the earth’s ecosystems (Dedeurwaerdere, 2014) and drew on the “Voices of the Poor” for the dimensions of human well-being—we consider poverty to be characterized as a multidimensional “lack of well-being.” Given that the “Voices of the Poor” study provides the dimensions of well-being and ill-being it identified, we are able to compare the dimensions of ill-being to the dimensions of poverty identified by the ATD/Oxford study. It should be noted that the “Voices of the Poor” study explored additional themes which cannot be compared to the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” such as the chapters on gender, the role of civil society organizations, and social fragmentation.

Table 5 summarizes the results of each study.

As Table 5 shows, there is, at least at first glance, a major overlap between the results of the two studies in the identification of poverty and ill-being (i.e. the multidimensional “lack of well-being,” according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment). Indeed, particularly regarding material components of poverty and ill-being, the two studies found nearly identical results, namely that lack of food (or material/social deprivation), lack of assets and money (insufficient and insecure income), and lack of livelihood (lack of decent work) constitute sub-dimensions of material deprivation that characterize poverty or ill-being. However, three important differences are worth noting.

Firstly, whereas “Voices of the Poor” includes “Security” as one of the dimensions of well-being, with sub-dimensions ranging from the absence of war (civil peace) to having confidence in the future, this dimension is understood differently in the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty.” The opposite of “Security,” titled “Insecurity, vulnerability, worry and fear” in the “Voices of the Poor” is broader, though it may be related to another dimension resulting from the Oxford/ATD study: “Suffering in the mind, body and heart,” as well as “Institutional maltreatment.” The former is described as including “negative thoughts and emotions that never go and can be overwhelming: constant fear of what could happen, of losing very scarce resources or assets, of what others will say upon being ‘found out as poor’; stress and anxiety caused by the difficulty of coping with uncertainty; shame related to living conditions” (Bray et al., 2019, p. 10). The dimension of “Institutional maltreatment” is also explained: “the failure of national and international institutions, through their actions or inaction, to respond appropriately and respectfully to the needs and circumstances of people in poverty, and thereby to ignore, humiliate, and in other ways harm them” (Bray et al., 2019, p. 14). Interestingly, the “Voices of the Poor” methodology guide asks research teams to explicitly ask about the security dimension of well-being, i.e. “Does (in)security figure in people’s definition of well-being? How do people define security? Are some households secure and others insecure? How do they differentiate between the two? What makes households insecure or at greater risk? Has security increased or decreased?” etc (Poverty Group et al., 1999, p. 25). This may explain why “Security” figures as one of six dimensions in the “Voices of the Poor”, but does not appear explicitly in the international report of the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty.”

Secondly, the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” introduces the concept of “Struggle and resistance,” which finds no counterpart in the “Voices of the Poor” (why it does not appear in Table 5). This is significant because the dimension is the “necessary counterweight to suffering and despair” (Bray et al., 2020, p. 5). It recognizes the skills, creativity, and solidarity that is mobilized among persons experiencing poverty, and thus acknowledges and restores a form of agency in an otherwise morally negative landscape. This is likely the result of including persons experiencing poverty in the study teams, rather than only academic researchers, who “rarely include dimensions of poverty that might be considered ‘morally positive’” (Godinot & Walker, 2020, p. 274).

Thirdly, the “Voices of the Poor” includes “bad social relations,” which covers (self-)exclusion, rejection, isolation and loneliness. This can be considered to overlap with the “social maltreatment” identified in the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty.” However, the latter report goes further in its analysis of relational dynamics. On one hand, it also identifies “institutional maltreatment” as “the failure of national and international institutions, through their actions or inaction, to respond appropriately and respectfully to the needs and circumstances of people in poverty, and thereby to ignore, humiliate and in other ways harm them” (Bray et al., 2019, p. 14). This is covered in another dimension in the “Voices of the Poor”; indeed, the dimension of ill-being labelled “Insecurity, vulnerability, worry and fear” includes “Exposure to stress in administrations & legal systems, persecution” (Narayan, et al., 2000). On the other hand, the ATD/Oxford report identifies “Unrecognized contributions” as one of nine dimensions of poverty. This, in turn, is specified as referring to the “knowledge and skills of people living in poverty” that are “rarely seen, acknowledged or valued. Individually and collectively, people experiencing poverty are often wrongly presumed to be incompetent” (Bray et al., 2019, p. 14). As with the dimension “Struggle and resistance,” this dimension acknowledges not only the difficulties and deprivations faced by persons experiencing poverty, but also their contributions and resourcefulness, which largely go unnoticed. These “hidden” dimensions are likely to have been revealed through the direct participation of persons experiencing poverty in the research process.

5. DISCUSSION

Using the methodological guide for the “Voices of the Poor” study and the Guidelines for Merging Knowledge and Practices when working with people living in situations of poverty and social exclusion (Ferrand et al., 2008), we discuss several dimensions related to the two studies, namely how “participation” was conceived in the two research projects; the role of the facilitators; and finally, the question of time in both studies.

5.1. Participation

In the “Voices of the Poor” study, the methodological guide specifies that the fieldwork is to make use of participatory and qualitative methods to “enable poor people to define, describe, analyze and express their perceptions on the study topics” (Poverty Group et al., 1999). This sets the general framework for the study, and further methodological recommendations advise on the methods and tools to be used and the issues to be covered.

The “Guidelines for Merging of Knowledge” go further in their understanding of participation, requiring face-to-face interaction and participation of persons experiencing poverty in all stages of the research. The guidelines thus demand that persons experiencing poverty contribute to the research as co-researchers, and not mere objects of the research. Based on the principle that we call here “transdisciplinarity,” the Merging of Knowledge comparatively puts a more demanding form of participation in place. According to this principle, knowledge is recognized as being held by a range of stakeholder groups, and not only academics. Here, persons experiencing poverty and those working alongside them (social workers, volunteers, etc.) are considered to hold knowledge from their experiences (experiential knowledge) and from their professional spheres (action-based knowledge), which are complementary to the theoretical knowledge of scientists hailing from different disciplines. In other words:

Merging of Knowledge affords equal status to each group of knowledge-holders (rather than considering some as “experts”) and brings representatives from all groups together in a debate towards achieving consensus, instead of importing outside “expert” knowledge for deliberation by those considered to have a lay perspective. (Bray et al., 2020, p. 4)

To achieve this equality in practice, rather than in mere theory, power differentials must be taken into account and countered (Godinot & Walker, 2020) using a variety of tools, including work in peer groups, active facilitation modes, support, and time.

In contrast, while the “Voices of the Poor” methodology proclaims the expertise of persons experiencing poverty (“The poor are true poverty experts”, see p. 2 of the guide), it does not place these persons at the center of the research. Indeed, certain pre-framed questions and concepts limited the participatory nature of the consultation exercise. As noted by Cornwall & Fujita (2012):

By defining a pre-determined list of topics, loaded with conceptual categories (“vulnerability,” “social exclusion,” “gender,” and indeed “the poor”) that have a very particular origin and framing power, the methodology guide frames what is possible for respondents to say and limits the opportunity for participatory analysis." (p. 1755)

This is because “one of the distinguishing features of participatory research is its emphasis on exploring people’s own categories and meanings” (Cornwall & Fujita, 2012, p. 1755).

5.2. Facilitation

The “Voices of the Poor” methodology guide encourages the training and recruitment of local researchers in order to “strengthen the local capacity for participatory and qualitative research” (Poverty Group et al., 1999, p. 4). The role of the facilitator here appears to be of a hybrid nature: ensured by the research team, facilitation includes both data collection and moderating focus group discussions, well-being rankings and other participatory tools and methods.

In the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” the role of the facilitator was equally crucial. However, the role conferred to facilitators in the Merging of Knowledge methodology differs from that in the “Voices of the Poor”. It includes providing support to reference groups by seeking to accompany, reinforce, and consolidate the knowledge, particularly of persons with the experience of poverty, whose knowledge from lived experience may be the most fragile (Ferrand et al., 2008). The accompaniment of the group by facilitators who have a thourough knowledge of the experience, interests, and issues facing the reference group is seen as some participants having the role of a “bridge” between the persons experiencing poverty and the remaining participants (Carrel et al., 2018).

5.3. Timing

The “Voices of the Poor” research was conducted at an extremely rapid pace, with the entire research process conducted in just over one year and the fieldwork completed within three months.

In contrast, time was an important aspect in the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty.” Indeed, the approach outlined in the points above cannot be rushed, and the support, autonomy, and participation rendered possible are the result of considerable investments in “creating an environment based on empathy, mutual recognition, trust, reciprocity, and non-abandonment” (Bray et al., 2020, p. 4). The pre-conditions for creating such an environment—including the ethical framework and confidentiality rules—are discussed in the Merging of Knowledge guidelines, included in Annex B to this paper. Moreover, in order to ensure no one is left behind, the Merging of Knowledge approach requires the tempo of the research to be set by the needs of the least experienced researchers, or those requiring the most time to comprehend others or to express themselves. Indeed, “people need time to reflect and find comfortable modes of expression” (Godinot & Walker, 2020, p. 272). This is true for both highly educated participants (e.g. researchers), who must learn to make their formulations comprehensible to all, as well as those with lower social position, linguistic ability or educational attainment who may not be accustomed to speaking in public. The careful attention paid to timing in Merging of Knowledge is reflected in the time taken to complete the study; “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” began in 2016 and ended with the publication of the final report in 2019.

The timing of both studies emphasizes the trade-offs between the different approaches. The latter benefited from a very large sample size, but due to the limited time it followed a consultative approach, whereas the former used deeply participatory methods over a longer period, reaching a smaller number of participants. More generally, the differences between the two studies shed light on the academic debate between large-N, quantitative studies, and smaller-N approaches inspired by anthropological and ethnographic practices. As Godinot & Walker (2020) put it, “There is, as always in research, necessarily a trade-off between internal and external validity or representativeness” (p.274) Despite the smaller sample size in the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” the iterative process allowed the research to go beyond the initial responses of participants and to engage in a de facto dialogue both within and between peer groups.

5.4. Reversing injustices in knowledge systems about poverty

By viewing transdisciplinary research involving persons experiencing poverty as “transformative space making” Marshall et al. (2018) explore the potential impact of knowledge production processes on system transformation. When highly participatory research moves away from “extracting information to empowering local analysts” (Chambers, 1994, as cited in Marshall et al., 2018, p. 2), it “can help create possibilities for addressing structural injustice in knowledge systems by enhacing the transformative agency of poor and propoor groups.” In their article, Marshall et al. (2018) use the example of research conducted in periurban India, which reversed an injustice in the local knowledge system by showing that disease outbreaks were not due to lack of hygiene on the part of the local, urban poor, but rather a result of the lack of amenities and maintenance provided by the authorities, which contributed to spreading disease. Much like that experience, the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” created new and transformative knowledge by identifying so-called “positive dimensions” of poverty.

Academic and policy literature often portray people experiencing poverty as those who engage in counterproductive behaviors, who “use less preventive health care, fail to adhere to drug regimens, are tardier and less likely to keep appointments, are less productive workers, less attentive parents, and worse managers of their finances” (Mani et al., 2013, p. 976). Instead of defining persons experiencing poverty solely as individuals with shortages (of food, work, education, assets, etc.), acknowledging dimensions such as “Struggle and resistance” or “Unrecognised contributions” sheds light on the “positive in the lives of people in poverty” (Bray et al., 2020, p. 6), their resourcefulness and inventiveness, their strengths and skills. As Bray et al. (2020) note, “All these multiple contributions typically go unrecognized or are treated with indifference by society, indifference that can cause people in poverty underestimate their own ability and skills” (p. 6).

In this paper, we have argued that the Hidden Dimensions of Poverty was the more participatory of the two studies and was able to arrive at such potentially transformative results precisely because of its long-term engagement with persons experiencing poverty, who participated in the research on an equal footing with academics and professionals. This allowed the study to reach results that may reverse the narrative according to which poor people are defined by their lack of resources, constituting a burden for society. Using more positive language and pointing to the struggle and resistance of persons experiencing poverty as well as to the valuable contributions they have to offer, such research may ultimately change the perspective and mental models associated with poverty, both for those studying and those experiencing it. As Godinot & Walker (2020) note, this is not, of course, the same as saying that “poverty should be considered as a positive”(p. 276). It could, however, lead to changes in the way that poverty is perceived, experienced, measured, and ultimately countered, once the results of the research have been reintegrated into societal and scientific practice (see 3.1.3 above)

6. CONCLUSION

Both the World Bank’s 1999/2000 study “Voices of the Poor” and the more recent “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” conducted by ATD Fourth World and the University of Oxford used participatory elements of poverty research in order to study the multidimensionality of poverty. In their own ways, both studies constituted considerable advances in poverty research. On one hand, the “Voices of the Poor” was the “only crosscultural study of this magnitude to date” which included “primarily poor, illiterate, and in some cases, remote, respondents” (Alkire, 2002, p. 189). On the other, the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” applied a highly participatory and demanding methodology on a broad scale, investigating common dimensions of poverty between countries in the Global North and South.

Despite the methodological advances and novel results obtained through each study, the analysis in this paper showed that the participation and role of persons experiencing poverty differed considerably between the two research projects. Indeed, the first of the two studies, the “Voices of the Poor”, included persons experiencing poverty on the basis of a consultative research approach. The methodological guide included a list of pre-framed questions to be asked and the study teams approached individuals, groups and communities using classical sociological tools such as interviews, focus groups as well as more novel participatory methods. Meanwhile, the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” used a deeply participatory methodology from the problem framing until the publication of results. Highly heterogeneous NRTs in the six countries ensured that persons experiencing poverty, practitioners, and university researchers were present at all phases of the study. Feedback loops involved peer groups composed of the three “knowledge types” at several stages in order to verify, complete, and enrich the analysis, validating it according to experiential knowledge, action-based knowledge, and scientific knowledge. Due to these differences, we consider the “Voices of the Poor” to be a consultation exercise (or, according to Wilmsen, 2008, “blueprint” participatory research), and the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” to be a process of knowledge co-construction, approaching the ideal-type of transdisciplinarity. We also predict that the social learning and empowerment of the project participants was greater in the ATD/Oxford project than in the World Bank study (see Herrero et al., 2018; Osinski, 2020).

We argue that the differences analyzed in the respective methodological approaches also has an impact on the results of each study. While at first glance, the dimensions identified in the seem to largely overlap, a closer look reveals that there are significant differences between the two. In particular, the latter includes dimensions that acknowledge and describe the more “positive” aspects of poverty experienced by those who live within it. For example, “Unrecognized contributions” made by persons living in poverty was found to be one of nine dimensions in the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty,” along with “Struggle and resistance,” which highlight the creativity, skills, and solidarity that result from the difficult situations faced by those who experience poverty. In addition to empowering project participants by allowing them to define the research question, to analyze and synthesize data, and to publish results, the outcomes achieved through the “Hidden Dimensions of Poverty” research constitute small steps towards reversing injustice in knowledge systems about poverty. This, in turn, has the potential to affect policy by emphasizing the contribution of persons experiencing poverty to society, rather than viewing them as a burden or source of societal challenges alone. By overturning injustices in knowledge systems, similar research may contribute to changes in policy choices in view of eradicating poverty.