Introduction

A lack of influential Continuous Professional Development (CPD) is a major concern of educators, parents, and governments, particularly in the rural context of developing countries like Nepal. Existing centrally-prescribed professional development programs that utilize off-site training approaches seem inadequate to influence teachers’ school performances. Reluctant to change, and non-responsive to changing situations, the programs are fixed and rigid. Excluding the concerned stakeholders, the existing programs are non-participatory. Such contextually non-responsive and non-participatory approaches have failed to support teachers to enhance their continuous professional development (MoE, 2017). In this paper, we argue that the participatory approach to professional development provides autonomy, thereby enabling teachers to explore their own context-responsive approaches.

The participatory professional development approach is conceived as professional co-learning in which the boundary of the trainer-trainee blurs and enhances the professional autonomy of the participants. Likewise, autonomy is an “independent capacity to make and carry out choices which govern his or her actions” (Littlewood, 1997, as cited in Ramos, 2006, p. 184). In this paper, we define teachers’ autonomy as their willingness and ability to choose educational experiences in the process of curriculum development and/or implementation (Wermke et al., 2019). It is based on our own experiences (see Wagle et al., 2019) that the teachers’ enhanced autonomy through participatory approaches enables them to develop agencies which readily address diverse contextual (and pedagogical) issues.

The need for participatory (and collaborative) culture is prioritized in the policy documents of Nepal. For instance, the Ministry of Education felt the need to create a collaborative, collegial, and purposive learning culture in the school. It stresses that the teachers “must be made more responsible, accountable, and trained as per need of the twenty-first century” (MoE, 2017, p. 172). Despite the policy suggestions, schools in Nepal have not been enabled to promote school-based professional development programs that reflect the changing paradigm of learning.

Much of the literature (Dhungel, 2016; MoE, 2017; Niraula, 2018) revealed that existing teachers’ professional development programs are not enough to enable them to develop local (i.e., school-based) curriculum, to implement curriculum effectively, and to establish a rich learning environment in the school setting. But, who is to blame? A 2015 study revealed that teachers in Nepal showed a willingness to widen their role from being limited to classroom teachers to “being a changing agent by motivating the students, changing the patterns of classroom instruction strategies and creating awareness in the stakeholders” (Dhakal, p. 24). This study, and other similar ones, show that the teachers in Nepal are not reluctant to change. They are just looking for supportive space to foster their skills.

We examined teachers’ professional development policy of Nepal and explored two major policy-practice gaps. First, teachers’ professional development policies encourage both the school and the teachers by using available resources to independently conduct CPD programs (NCED, 2016b). Despite this, teachers are unable to engage in the school-based CPD and curriculum development. There are many possible reasons for which Niraula (2018) identified headteachers’ incompetency as fundamental to this policy-practice gap. Unfortunately, no study searches for the reasons behind this incompetency. Next, although curriculum development processes and professional development programs suggested a participatory approach to make teachers capable of developing curriculum (CDC, 2007; NCED, 2016a, 2017), teachers are unable to develop school-based curriculum in practice. They are unable to transfer knowledge, which they gain in the training programs, into a real-world scenario. Though the policy has envisioned self-motivated, responsible, and autonomous (self-determined) teachers, the teachers are habitually following the centrally-designed curriculum and evaluation procedure. The schools have made no effort to engage teachers in the curriculum development process.

In line with Wagle et al. (2019), we felt the need to explore ways to strengthening teachers’ agency for contextualizing teaching and learning in the basic level education in Nepal. To meet this goal, we explored additional research studies related to context-responsive approaches to teachers’ professional development. In Poyck et al.’s (2016) study, the relevancy and practicality of the existing teachers’ training programs remained questionable. Perhaps the contextually non-responsive and non-participatory training model was an outdated model that did not provide sufficient space for meaningful interactions and self-reflection from teachers. Unlike the existing model, Zeichner (2003) suggests adopting a school-based participatory model as an alternative to enhance the professional development activity of teachers. Following Zeichner’s guidelines, our focus was on empowering teachers to develop the curriculum as a part of professional development. We saw the possibility of contextualizing teaching and learning through cross-sectoral (two different sectors, i.e., curriculum and CPD in our context) and cross-contextual (different contexts) teacher collaboration (Hamilton, 2018). The needs-based curriculum reformation through teachers’ agency (Jenkins, 2019), affective agency for social change (Ferrada et al., 2020), and the enhancement of teachers’ professional agency through professional development encouraged us to engage teachers in collaborative action-reflections, very similar to transformational activities. It encouraged us to explore transformational approaches to “(re)claiming agency” as a basis for their situated educational practices (Lambirth et al., 2019, p. 387).

Because we are teachers and teacher-educators, we took a social responsibility of influencing self and the teachers rather than blaming teachers for their inefficiency in addressing contextual issues. These social and professional responsibilities prepared us to believe that as adult learners, teachers could collaborate and feel the need for their own context-responsive approaches. By being proactive problem-solvers, teachers could develop their own strategies (Dhakal, 2015) for joyful classrooms (Nepal, 2015). To this end, we believed exploring school-based participatory approaches would not only solve contextual issues but would also dig deeper to uncover the real problems teachers experience in real settings. Doing so, we went beyond expert-based and/or off-site training-based current practices, where problems and solutions were envisioned from a distance and based on past issues or other contexts. Instead, we focused on lived or current problems, seeking school-based collaborative learning.

The exclusion of teachers in the creation of school curriculum was a living problem that could be addressed by a democratic, collaborative, and inclusive participatory process (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005). Perhaps such an exclusion of teachers was marked by “technical interest,” which Habermas understands as a disempowering approach that controls human agency in the construction of knowledge (Grundy, 1987). In other words, the existing development process was less than democratic, so we explored the possibility of a democratic process. Inspired by Habermas’s emancipatory interest (see Kemmis, 2008), we envisioned an emancipatory PAR approach that could engage practitioners in critical self-reflection. In our case, the emancipatory PAR could continuously improve teachers’ practices to envision the relevant and context-responsive professional development in the rurally located schools of Nepal. As per emancipatory interest, we needed a critical component in our context-responsive professional development.

It was evident from past experiences (e.g., Niraula, 2018) that the teachers could solve immediate problems, but they could not develop their own approaches that address present and future problems. Further, teachers would continue seeking support from others and experimenting with new approaches which might not enhance their agency. By rethinking alternative approaches, teachers could continuously explore contextual approaches, develop their own framework for continuous professional development, and influence self, others, and the school rather than depending on others. Thus, like Schibeci & Hickey (2004), we regarded teachers’ professional development as a continuous learning process of teachers who apply their learnings to improve their pedagogical practices. For us, teachers’ professional agency was their active ability to take responsibility to both develop and/or implement curriculum autonomously and to continuously develop and practice context-responsive pedagogical approaches.

Thus, our PAR project for the school-based continuous professional development of teachers through collaborative actions and reflections for curriculum development and implementation spanned from July 2017 through July 2019. We conducted this PAR project with a transformative aim, asking: How can we support basic level teachers in developing context-responsive approaches for enhancing their professional agencies in the school?

Our Positionality

Taking a hermeneutical approach to meaning-making, we sought to empower teachers for their autonomous or self-directed actions by adopting the Habermasian notion of “emancipatory interest” (Grundy, 1987). Emancipatory interest is not a controlling and manipulating interest but an empowering interest that creates a democratic space for communication and develops the agency of the participants (Grundy, 1987). Democratic space refers to an inter-subjective and inclusive space, which Habermas calls a “communicative space” that exists between individuals with reciprocal recognition, where they discuss, share, and develop mutual understanding freely (Kemmis, 2008, p. 5). In taking this approach, we created a democratic space for communication in which teachers could reflect on pedagogical approaches, discuss areas for improvement, seek new approaches, and move ahead with reflective actions. Our transformative aspiration (see Luitel & Taylor, 2019) prepared a contextually-relevant communicative space for enhancing teachers’ agency and developing a sense of professional responsibility. Critical, or emancipatory, PAR enabled us to meet these ends, which we discuss in the following section.

Research design and methods

As earlier discussed, we chose a Participatory Action Research (PAR) design to explore context-responsive approaches of the basic-level teachers of a school in rural Nepal. We initiated this PAR project at a community high school that had teachers and students from diverse backgrounds. Teachers included 16 basic level teachers (4 females and 12 males), who teach in grades 1–8 (the children are 4 to 12 years old). Although the teachers had received some formal and informal training in the last five years, none of them had participated in any interdisciplinary professional development workshops. The teachers were more familiar with lecture than practical, hands-on methods in their teaching and learning, and they were limited within the four walls of the training room and classroom.

Our choice of the emancipatory PAR was to enhance teachers’ professional practices through building mutual collaborative relationships. The collaborative relationship is “a framework for effective practice” (Brydon‐Miller & Maguire, 2009, p. 83). This relationship seemed to fit well in the Nepali context, as we have recently adopted a federal democratic republic. In the context of Southeast Asian teachers’ professional development, their community-driven culture inherently promotes continuous learning through community engagement (Alam, 2016). For example, rurally-located communities of Nepal celebrate collaborative culture in their everyday social practices like mela (fair), parma (the social practice of exchanging labor for labor), jatra (festival), and other religious rituals in which people voluntarily gather and discuss local issues and take social responsibility. This culturally-informed collaborative practice, together with readily available policies that suggests for collegial and empowering professional development programs, provided us a suitable background to initiate participatory action research as a foundation for teachers’ professional development. The cyclical processes of planning, action, observation, and reflection of PAR could provide (additional) formal space for communal learning (Lawson et al., 2015).

Also, we found PAR to be a context-responsive approach because every teacher had an agricultural background. The continuous process of cultivation and harvesting in agriculture seemed similar to the cyclical process of PAR—planning, action, reflection, and planning again. Having the possibility and potentiality of “transformational liberation” (Lykes & Mallona, 2008), PAR was a seemingly suitable approach for changing teachers’ behavior. Here, transformational liberation refers to recognizing individual and collective potentiality and praxis.

When the headteacher of the research site invited local university researchers for the school reformation, we (Shree and I, the Ph.D. students) reached the school and began strengthening our familiarity with the school context. Intending to explore contextual issues, we reached out to the teachers in their day-to-day setting. By being inclusive (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005; Lawson et al., 2015) we created a suitable and trusted environment through our twelve different visits in eight months period. We gained familiarity with the teachers, students, headteachers, and community life through rigorous in/formal discussions and interactions. We used consent forms to enforce ethical procedures of informed consent, confidentiality, voluntary participation, and dissemination of results. We hoped to have created a democratic communicative space for genuine consensus-building (Habermas, 1972) and elevated available skills, knowledge, and teachers’ experiences collaboratively. We valued both human and non-human resources (such as computer skills and knowledge of the teachers and computers) to address contextual needs through an ideal speech situation. Here, the ideal speech situation refers to a safe and free environment where all can interact in the decision-making processes.

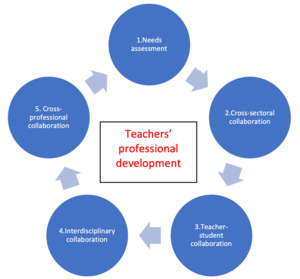

We continuously interacted with the teachers and discussed formally (in a meeting) and informally (causal talks) to explore the contextual needs and approaches. The headteacher and the teachers asked us to lead the project. Accordingly, we participated in a need-assessment workshop for collective reflection and planning that progressed through the other three collective, reflective planning workshops (see Fig.1). Each workshop guided the next cycle, where we continuously asked and reflected on the questions: How did we feel and think about collaborative activities? What worked and what did not work? How can we improve our collaborative activities?

We not only reflected on our educational practices individually and collectively in the workshops but also interacted informally in the teachers’ room, at tea shops, in the school premises, on the way to school and in educational visits. We also interacted formally in school meetings in order to validate the data and gain additional insight. We recorded the visual data texts (such as photo and presentation slides) from our PAR action-reflections in our reflective journals. We reflected on our journals, presentation slides, and photos, adopting an “everyday life approach” by examining both looked and overlooked approaches (Given, 2008, p. 307). Looked approaches refer to a common approach that we discussed in the action-reflection process; overlooked approaches refer to the approaches which were taken for granted at the time of action-reflection and were uncovered only in the process of writing. Then, while writing, we (the authors) connected all approaches, developed them into a narrative form, and made sense of them. The study of Ahmad et al. (2016), which adopted Eneroth’s (1986) process method, helped us identify multiple unique approaches that evolved during the action-reflection process which we have presented in the following section as themes.

Context-responsive Approaches of Teachers’ Professional Development

We carried out the PAR project on school-based teachers’ professional development from July 2017 to July 2019. The project was comprised of four emergent phases: needs assessment phase, Cycle 1, Cycle 2, and Cycle 3. During the process, a theme emerged from each phase (context-responsive approach). Thus, we uncovered the four context-responsive approaches: 1) cross-sectoral collaboration; 2) teacher-student collaboration; 3) interdisciplinary collaboration; and 4) cross-professional collaboration. We share the four context-responsive approaches in the following section.

Cross-sectoral Collaboration

Here, cross-sectoral collaboration refers to the collaboration between Shree and Parbati who worked with curriculum and CPD, respectively. In the participatory need assessment phase (from July 1, 2017 to May 31, 2018), we first planned to assess the needs of the basic level teachers through participatory methods. Then, we participated in multiple discussions and interactions, building mutual trust and harmonious relationships in assessing the needs of the teachers. Our assessment revealed five major needs of the teachers: 1) contextualized teaching and learning, and/or construction and use of locally available resources; 2) continuous (collaborative) professional development of teachers; 3) use of ICT in teaching, learning and assessing; 4) development of school-based curriculum and practice; and 5) increased parental participation for students’ learning at the school.

After identifying the five major needs, Shree took leadership of the first need—contextualized teaching and learning, and use of local resources—and Parbati chose the second need—to facilitate the continuous (collaborative) professional development of teachers for implementing basic level curriculum. Later, not limited to merely improving content knowledge and teaching skills, we (teacher-researchers, Shree, and Parbati) decided to participate in collaborative activities in the process of contextualizing curriculum as a part of professional development.

Our decision of partnership turned into cross-sectoral collaboration and the integration of the two major issues (sectors): curriculum development and teachers’ professional development. Here, the cross-sectoral collaboration refers to the collaboration of the curriculum and CPD designers and implementers. Therein, we decided to establish a suitable space for contextualized educational practices (Barane et al., 2018) by collaborating on two PAR projects. Then, we planned, acted, and reflected to create a democratic space for enhancing professional agency. In Geiger’s (2016) words, we created safe spaces through “public discussion” or collective reflection and individual reflection, fostering “semi-private space” that is illustrated in Figure 1.

We collaborated for the five reasons: 1) to save teachers time; 2) to become role models (Bandura, 2001; Mezirow, 2000) for the teachers; 3) to develop “social capital” or to build mutual relationship among stakeholders in a resource-constrained community school (Yoon et al., 2017); 4) to use collaboration as a tool of professional development (Black, 2019); and 5) to avoid possible associational challenges in the research context (Luitel & Taylor, 2019). We expected that the collaborative space could create an ideal space for the collaborative praxis.

We mutually distributed our responsibilities to face possible challenges. Accordingly, Shree took the responsibility of orientation and explanation and Parbati looked after the needs assessment. As a PAR facilitator, Parbati tried to create a democratic communicative space for unforced consensus-building by involving teachers in individual and collective self-reflection and action in dialogic discourse (Kemmis, 2008). In doing so, we adopted both formal and informal approaches like interactions, workshops, and discussions.

Teacher-student Collaboration

In Cycle 1, we mainly focused on participation in the collaborative activities of contextualizing the curriculum. For it, we formed a professional learning community. The community was comprised of multiple stakeholders (the headteacher as the leader of the teachers, all the basic level teachers as teacher-researchers, and the high school teachers as critical friends) who participated in planning group projects, in their implementations, and in sessions dedicated to share reflections on planning and implementations.

First, we planned for three methods of teaching—project-based, inquiry-based, and arts-based—for contextualizing the curriculum process. Project-based learning is a solution-seeking approach to a given problem (Behizadeh, 2014); inquiry-based is a scientific inquiry approach of learning that involves learners in orientation, conceptualization, investigation and conclusion (Pedaste et al., 2015); arts-based/play-based is an aesthetic approach of learning with fun integrating arts and/or games. We agreed on arts-based/play-based project work for Grades 1–3, inquiry-based project work for Grades 4–5, and project-based group work for Grades 6–8. After participating in the orientation sessions on the approaches to contextualized curriculum, all the teachers, according to their levels, agreed to develop one group project from their regular lesson, practice it in the class, and reflect collectively in the meeting.

Then, realizing teachers’ discomfort of practicing the four types of projects and portfolios at once, Shree conducted an individual orientation. Additionally, Parbati initiated an on-spot support to critically reflect on teachers’ control over students and projects, to critically reflect on cultural reproduction of curriculum, and to promote the democratic communicative activities through self-reflective questions. For instance, Parbati engaged the teachers in their self-reflections, explored their hindrances, and supported them to improve their learning experiences. The majority of the teachers critically reflected on their practices.

Here is an example of how a teacher reflected on his participation and with regret: “I made two mistakes. I realized after the class. I was not well-prepared.” In their role as the PAR facilitators, Shree and Parbati continuously discussed and reflected on the progress of their projects based on these questions: How is your project going on? Are you enjoying it? Do you have any challenges? How will you improve your practice?

Learner-Centered Pedagogical Knowledge.

Before the meeting, the teachers critically reflected on the collaboration with their students and their experiences of pedagogical activities. The Grade 1 teacher, who initially had some trouble getting started, ultimately collaborated with her students and continued her project design process in upcoming lessons. Moreover, she enjoyed her class and the engagement of her students outside the classroom. Students would move around, writing the names of the real objects of their surroundings and sketching pictures with natural colors. Similarly, going beyond collective decisions, another teacher conducted an inquiry project in Grade 6. Her pedagogical act involved a student-centered approach as she discussed the possible project and the method of the running lesson with her students, and pursued the students’ choice and the appropriateness of the content of the curriculum rather than her pre-planned method and/or given project-based method.

In the meeting, all the basic level teachers shared their experiences of conducting group projects in their classes. The majority of the teachers enjoyed doing the project and collaboratively decided on the topic of the project as per the interests of the students. They found the students joyful and active in the group projects. However, a few teachers found that a group project did not engage all the students. They wanted to improve the participation of the students and address the challenges of evaluation of the group projects. We noticed that the teachers were confident and happy in the reflection session.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Here, the interdisciplinary collaboration indicates the collaboration among the teachers of multiple disciplines, such as English, Mathematics, Science, Social Studies, and Nepali. In Cycle 2, we continued our collaborations to improve our professional learning through teacher-teacher collaborations.

First, realizing the challenge of equal participation of all the basic level teachers, (mainly, Grade 1–5 teachers) in the collaborative practices, we discussed and explored how we could increase active participation of all teacher-participants, particularly those from lower grades. Based on discussions, teachers decided to increase their knowledge and skills with computers. Then, we worked with six instructors among the teachers (the majority from Grades 6–8), two female and four male teachers who agreed to support each other. We chose the Heads of the Departments (HoDs) as the leaders of each group. Doing so, we moved beyond conventional trainer-trainee contradictions (Freire, 2005) and decided to be involved in collaborative practices to “check ideas with others” (McNiff, 2017, p. 10) in the collegial learning process.

The teachers prepared PowerPoint slides reflecting on their experiences with ICTs use and professional development, particularly on: 1) experiences of comfort; 2) experiences of discomfort; and 3) areas of improvement. These categories emerged in the process based on these questions: What worked and what did not work? How can we improve our collaborative activities? Five of the teachers, who were familiar with computer basics, facilitated the process. Gradually, the teachers got engaged in the formal interaction and then informal talks. Soon, the room was full of activities, which Parbati noted in her reflective journal.

The Mathematics teacher said: “I am zero in computer.” Another Social Studies teacher, who once taught his colleague, said, “We taught you in your school days, now, come and teach us.” A Nepali female teacher was talking to herself, saying, “I prepared my master’s thesis a long time back and forgot it.” A Nepali male teacher who was sitting in a corner said, “I learn to open a shop after retirement.”

The teachers’ interaction was filled with critical self-reflection, humor, and planning tbeir personal futures. It seemed interesting, joyful, effective, and easy to get interdisciplinary support. Further, we observed two types of collaboration: HoD-teacher collaboration and teacher-teacher collaboration. For instance, HoDs collected and managed their experiences in the computer slides in collaboration with the teachers of their concerned departments, whereas the remaining teachers were involved in peer learning processes through observation, action, and reflection.

New leadership.

Going beyond collective decisions, a Grade 6 teacher took leadership in collaborative activities. He, who believed in learning by doing, took the role of a mentor in the collegial learning process. For instance, he had remarked confidently in the reflection phase of Cycle 1, “We need to do ourselves before we teach…. If I get materials, I can set the lab. I am willing to learn hardware…” In Cycle 2, he initiated facilitating all his colleagues who asked for support from him. His proactiveness is more visible in Parbati’s reflective journal entry, dated November 30, 2018, where she observes: “…he was moving from table to table assisting teachers… I found many of the teachers asking him comfortably and getting support from him rather than from HODs … He was enjoying assisting his colleagues.”

In the meeting, all five Head of Departments (HoDs) presented their experiences. Four of them used PowerPoint slides and one presented orally. Through their presentations, we uncovered many comforts, discomforts, and areas for improvement in collaborative learning.

For instance, collegial learning minimized the hesitation of group learning and, thus, improved relationships, built confidence, and made learning fun. We learned that collegial learning created favorable space for familiarizing computer use, reflection, and autonomous actions. Acknowledgment of interdisciplinary feedback and changes in the planning, continuous collaboration, and reflection, informal collegial learning environment, encouragement of interdisciplinary cooperation and coordination, and appreciation of integrated projects enhanced the autonomous activities of the teachers. Despite this, we explored an area of improvement: collaboration between the teachers, the department heads and the headteacher.

Cross-Professional Collaboration

Here cross-professional collaboration refers to the collaboration of non-teaching professionals (artists) and teaching professionals (teachers). Based on the reflection of the Cycle 2, in Cycle 3 we continued our two best practices: collaboration and integration of arts in teaching and learning of Grade 1–3 teachers.

First, along with Grade 1–5 teachers, we sat for the reflection of Cycle 2, and planning for Cycle 3. We noticed that the teachers did not seem as enthusiastic as in previous discussions. They were not sharing their smiles as they typically did. When we were engaged in discussions, we uncovered mixed feelings about participation in collaborative projects. Parbati’s journal entry, dated January 17, 2019, showed teachers’ critical reflection on their ongoing engagements. “We learned many things but still we are confused.” Although teachers realized that they learned from collaborative activities, they felt biased: “…all the benefits are for the HoDs.” Perhaps, high school teachers’ domination continued to some extent in this phase: “Should the teacher of higher grades always speak?” Such awareness of biases made them feel excluded in the learning process: “Why are we excluded from the opportunity of learning?”

The journal entry uncovered that basic level teachers decided on their pedagogical approaches. That motivated us to create a better decision-making space, where every member could share benefits equally (S. P. Dhungana et al., 2017). We began to explore ways that we could make space for all research-participants to experience equal benefits from collaborative practices. Then, we became involved in individual and collective reflection sessions with the teachers, headteacher, and the HoDs who showed us the pathways to uncover and live professional value, collaboration, improving professional practices (P. Dhungana, 2020) through dialogue (Delong, 2020).

Intending to enhance teachers’ ability to reflect critically and respecting teachers’ voices and basic level students’ choices, we, along with Grade 1–3 teachers, adapted artivist pedagogy, the pedagogy of teacher-researcher who integrates art for creative expression (Mesías-Lema, 2018). Breaking away from the banking pedagogical approach (Freire, 2005), we planned to create an art book in a week-long project, involving an artist, the teachers, and students. We chose art as all the students were interested in arts-based projects. First, we tried to identify an artist among us, but when no one had that skill set, we invited a local artist to the school to work in collaboration with the students and the teachers.

Then, we (including a local professional artist) gathered in the hall to draw and paint local artifacts. The teachers discussed the content among themselves. Noticing teachers’ difficulty in managing all the three classes in the hall and engaged in meaningful discussion, Parbati involved the students in free artwork. Including the students was a spontaneous choce that led to some confusion and chaos. However, rather than separating teaching and learning as distinct things, we decided to include students and learn together with them. Starting the next day, we, including teachers and students, sat together and learned together with the artist. In negotiation, we (Parbati, the teachers, the local artist, and the students) discussed and chose the contextual artifacts. Then, we sketched the pictures of the local artifacts. During free time, the high school students and the headteacher joined the integrated class and remained engaged with them.

Curriculum integration.

On the third day, teachers decided to individually develop three different books of Nepali and English alphabets and numbers (Maths). This decision revealed the contextual needs and the capability of the teachers to develop context-responsive school-based curriculum and curriculum integration. Besides, a joyful learning environment and active participation of the teachers and students in the process of curriculum development transformed the existing teaching and learning process. For instance, Parbati’s reflective journal entry dated February 8, 2019, recorded a teachers’ remark: “I wish there was no holiday. We could continue learning.” We felt all the teachers and students were happy and wanted to spend more time in that environment. Further, Parbati noted: “This aesthetic interest was joyful for all including myself. This was the most joyful and engaging activity!”

Thus, through continuous collaboration and reflection, the teachers developed aesthetic agency and thereby created a positive and joyful learning environment among students and teachers. This transformational professional development process came up with three art books which both the teachers and the students could use as context-responsive (and integrated) school-based curriculum. It prepared a favorable space to motivate teachers to enhance their creativity, to develop teachers’ proactive agency (Jenkins, 2019) and cognitive strength (Bandura, 2001). Further, it enhanced teachers’ autonomous decision-making, teachers’ creativity, and harmonious relationship between students, colleagues, and local professionals. This cross-professional collaborative learning further inspired teachers for cross-professional collaboration.

For instance, going beyond his usual lecture method, a Grade 8 teacher conducted the first practical cooking class in the school by perceiving himself as an autonomous and self-directed teacher within the classroom arena (Wermke et al., 2019). Perhaps he was influenced by the cross-professional collaboration of the teachers that led him to choose curriculum content and the method in collaboration with the students, where he conducted a practical class in collaboration with Grade 8 students, a colleague, and a kitchen staff member.

Finally, all the teachers showed willingness to continue their best practices. They expressed their ability to develop a school-based, integrated, and contextualized curriculum. They showed enthusiasm to continue collaborative practices. Thus, the cross-professional collaborative participation enhanced teachers’ autonomy through planning projects, choosing context-responsive pedagogical approaches and implementing them to improve their professional practices. The participatory approach worked considerably well to explore context-responsive approaches of teachers’ professional development.

Reflection: A participatory framework of/for teachers’ professional development

Adopting a participatory approach with emancipatory aspiration, we created a favorable and democratic space that supported basic level teachers to develop context-responsive approaches and thereby envisioned a participatory framework of/for teachers’ professional development.

Teachers’ emancipatory aspiration enhanced their professional agency in different phases of the PAR process. For instance, the reluctant teacher, who was guided by the “technical interest,” and who would control the learners and the learning environment, gradually moved out of the comfort zone, overcoming the doubt of adopting context-responsive approaches. The communicative teacher, who was guided by the “practical interest,” sought a consensual understanding of the learners to explore and enhance their pedagogical approaches. The participatory teacher, who was guided by the “emancipatory interest,” took the active initiative and empowered learners by creating a suitable learning environment through dialogues to explore and practice their own context-responsive approaches.

Additionally, the participatory approach with transformative intent developed a reciprocal relationship between students, teachers, headteacher, and local artists via questioning self and improving action continuously. Further, the collaboration between teacher and student enhanced student-centered pedagogical approaches and the teachers’ connective, collaborative, and pedagogical autonomy. This capacity for autonomous actions showed teachers’ professional growth (McNiff, 2017) and “collective agency” (Bandura, 2001). For instance, the teacher-student collaboration helped to internalize group works, to develop a sense of integrating curriculums, and to develop a mutual relationship between teacher and students.

Similarly, the collaboration of the headteacher and the teachers made the professional learning environment harmonious. Interaction among basic level and high school teachers created an interdisciplinary collaborative environment for collegial learning and support in need. The collaboration between the researchers and the teachers created a cross-professional sharing environment that opened up a favorable space for on-the-spot support. It also created an opportunity for self-reflection. In short, the multiple layers of collaboration developed a democratic space for teachers’ autonomy to connect the existing curriculum with their context.

The following ten conditions provided a safe space for context-responsive approaches of teachers’ professional development: 1) The context responsiveness of PAR action-reflections rejuvenated process-focused pedagogical approaches that motivated teachers to act autonomously; 2) An explanation of the real needs set out the self-directives of the teachers; 3) Respect for available resources and local knowledge created a platform for cooperation and collaboration; 4) Flexibility in adapting context-responsive collaborative approaches created a favorable environment to participate actively; 5) On-spot support and feedback motivated teachers that involved them in self-reflection and thereby improved their action; 6) The researcher or facilitator’s “walking the talk” (Chevalier & Buckles, 2019) built trust among facilitators and teachers; 7) The inclusiveness provided the opportunity of receiving and giving support, trust, and care in need; 8) The establishment of a professional learning community that intended to create a communicative space provided the opportunity to speak, to listen, to ask, and to respect all voices (Habermas, 1972); 9) By being with the teachers, and acknowledging the “preciousness and indissoluble uniqueness of each human life,” it enhanced their sense of interconnectedness (Kemmis, 2008, p. 134) as they took professional responsibility and ownership of professional development activities; 10) The investment of ample time with the teachers in their real setting enhanced harmonious relationships among facilitators and teachers.

In short, we can facilitate collaboration between teachers and researchers to raise the teachers’ professional agency in ways where the teachers become autonomous learners. However, “genuine participation” is a prerequisite (Chevalier & Buckles, 2019). Teachers’ collaboration could be enhanced working with the prescribed framework (Gore et al., 2017) but embracing emergent context-responsive collaborative approaches strengthens innovative pedagogical thinking and curriculum integration skills of the teachers.

The collaborative participation of parents, community members, SMC and PTA members, government representatives of the local bodies, and district education office could motivate teachers to develop and/or implement the local, integrated, and contextualized curriculum at the basic level. Such context-responsive approaches are participatory approaches which could be an effective professional development framework for school teachers of similar contexts.

Furthermore, the authors of this paper foresee teachers continuing to gain autonomy, i.e. independence, from school administration and the state. This will allow teachers to successfully develop and disseminate authentic, contextualized school curriculums, respecting all the contextual needs, context-specific artifacts, indigenous knowledge, and lived experiences of the teachers. Overall, we envision teachers as autonomous learners who can create democratic space through a context-responsive collaborative praxis. PAR as such provides a suitable and safe context for autonomous and collaborative activities and critical reflection, which, in the long run, enables teachers to develop their professional agency and thereby develop their own professional development framework. PAR, with emancipatory aspiration, opens up democratic spaces not only to the teachers but also to the curriculum and CPD developers and implementers, teacher educators, teacher trainers, facilitators, students, head teachers, and non-teaching professionals of other contexts, too.