Introduction

As most of our planet contends with the harsh reality and fallout from the current pandemic, it can be difficult to imagine a future that is not simply going “back to normal” but is one in which we are able to work together to address challenges in significant and creative ways. That is exactly what the Future Creating Workshop (FCW) (Brydon-Miller et al., 2017; Tofteng & Husted, 2006) process is designed to do. Grounded in Critical Utopian Action Research (K. A. Nielsen & Nielsen, 2006), this approach provides participants with an opportunity to identify key challenges and barriers to addressing problems they face as an organization or community, then to generate innovative and expansive ideas for moving forward, and finally to consider how they might move forward together toward realizing their dreams for the future. Under ordinary circumstances, this process is conducted in face-to-face community settings and can take anywhere from an afternoon to a few days over an extended period of time. In the case described here, and in subsequent workshops we’ve conducted since this one was carried out, we have adapted the process to be done online in either an asynchronous or mixed real-time/asynchronous format. This article describes the online adaptation that we created, sharing the online technologies used, some of the facilitation dilemmas we confronted, and the lessons learned. In so doing, we hope that this article can be useful to other action researchers seeking to address current challenges in online community-engaged spaces.

Critical Utopian Action Research draws upon the work of the critical theorists of the Frankfurt School, Kurt Lewin’s early contributions to the development of Action Research, and the work of German philosopher Robert Jungk to create an approach to inquiry in which “the critical role of the researcher is to be active in the world by creating proposals for new democratic structures in society” (Tofteng & Husted, 2014, p. 232). One critical aspect of CUAR is the creation of what is known as “free spaces” (Bladt & Nielsen, 2013, p. 374) in which participants are able to engage and contribute in a context apart from the usual constraints of power and control. The structure and facilitation of the FCW processes work to make this possible by limiting the ability of those in power to set the agenda and by providing opportunities for democratic participation by all involved.

The FCW process itself consists of three distinct phases: Critique, Utopian, and Realization. The FCW is anchored around a specific theme or question that serves as the focus for the process. In the Critique Phase, participants are encouraged to identify specific constraints to achieving the goal set out in the overarching theme. In a traditional face-to-face FCW, this takes the form of short observations or points contributed by participants and captured by facilitators on large sheets of paper posted on the wall. Once all the contributions have been recorded, participants vote on which points are most important to them, and then engage in a collaborative process of integrating the points into key themes. At this point participants may be encouraged to reflect on the themes in a more open-ended way by creating a silent play in which they work together in small groups to enact one of the themes without speaking. Once this first phase is complete, which can take up to a full day, the Utopian Phase follows the same basic protocol, but focuses instead on working together to create an ideal vision for the future, as it pertains to the overall focus of the workshop. Finally, in the Realization Phase, participants are invited to work to create concrete proposals for action to move toward the utopian vision while keeping in mind the constraints identified through the critique. The Realization Phase is sometimes set apart from the first two components of the process to allow ample time for participants to generate specific recommendations for action (L. D. Nielsen, 2006; Tofteng & Husted, 2011, 2014).

Context

In Autumn 2019, before COVID-19 hit the U.S., we (Miriam, Mindy, and Gail) were faced with a concern in our practice as leaders of an educational leadership program. The program, Mandel Teacher Educator Institute (MTEI), is a two-year cohort-based program that brings together leaders from Jewish educational institutions from the United States, as well as Canada, South America, and Israel. In pre-COVID-19 days, cohorts would meet three times a year, for four days at a time, in Skokie, Illinois. Rooted in principles of collaborative inquiry, learner-centered pedagogy, non-violent communication, and deep study of Jewish texts, MTEI seeks to build healthy relational learning communities where robust new knowledge of instruction leadership is constructed (Dorph, 2011). While the program was created in 1995, the last decade has seen strong growth of a graduate network, seeking to bring together all graduates of MTEI for continued learning and professional development. Our concern centered on the graduates’ engagement with the network, and the sense that we struggled to create a relational learning community in this space. Part of our inquiry focused on the fact that other than previous in-person graduate conferences, the recent work of the network has occurred online—first via conference calls, then via Zoom, and then adding a dedicated asynchronous online space (Edmodo) for sharing of resources, engaging in discussions about problems of practice, and participating in asynchronous structured discussions such as a Slow Book Chat (a book discussion taking place over multiple weeks) and Consultancy Protocols (McDonald et al., 2013).

Implementation

In January 2020, we asked Mary to join us in thinking about how we might be able to create a Future Creating Workshop (FCW) in online spaces, so that we could dream with our graduates about how to build stronger relational structures for learning. Mary had extensive experience facilitating FCWs and was curious how it might work in an online space. The guiding question for our inquiry was: What are the essential components of an online relational learning community that can sustain and deepen educators’ professional learning? As action researchers, we understood that to make sustainable change to our graduate network it was important to engage our members in this visioning process. The following section describes each step of our implementation of this online Future Creating Workshop process.

Invitation

We began with an email invitation to all 250 members of our graduate network, which detailed the question we were thinking about, why we chose FCW, and the time commitment required. Twelve people responded that they were interested.

-

We sent a confirmation email to those who responded, reminding them that this was a research process and that the data could be used in presentations and an article. We asked that they confirm receipt of the email. This served as their informed consent for participating in the FCW. (The University of Cincinnati IRB designated this study as Non-Human Subjects Research, a category that they assign to research that does not meet federal guidelines for generalizability.)

-

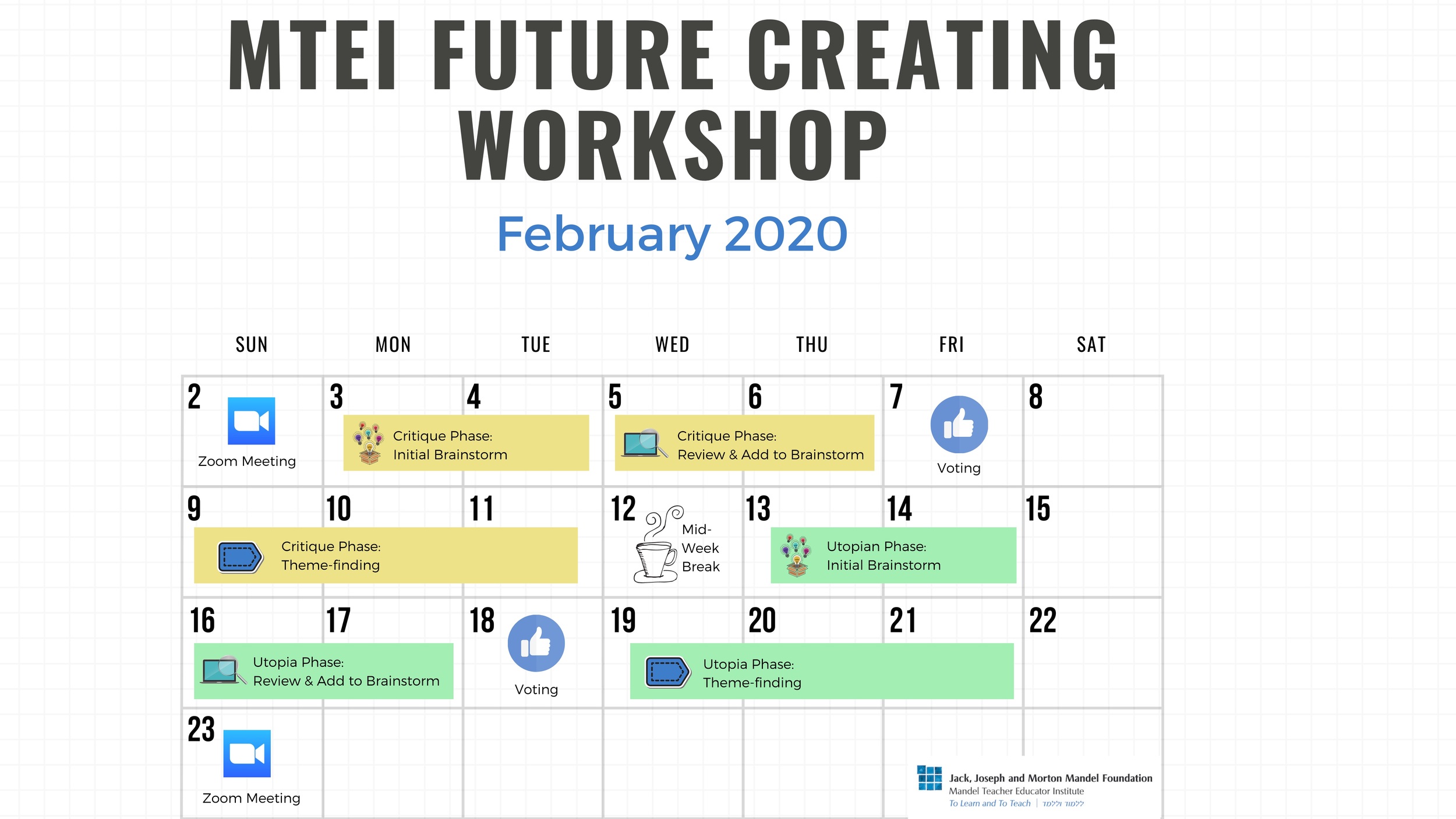

The following calendar was also sent to all who responded to help create a visual sense of a process that would take place over time, synchronously and asynchronously.

Introductions

Because our participants spanned four different cohorts, it was important to help people get to know each other and build some connection in order to create a sense of community. Before beginning the FCW process, we sent out a Google Form asking participants for a photo of themselves and brief responses to the following:

-

I’m excited to participate in the Future Creating Workshop process because…

-

To get my creative juices flowing, I…

-

I chose this picture because…

We were intentional about choosing questions that related to the process and included an opportunity to share a personal note. Autocrat (a Google Sheets add-on) was used to turn Google Form responses into a scrollable Google Slides deck titled Meet Your Learning Partners. The Google Slides deck allowed the group to have asynchronous conversation via the comments feature before the FCW process began.

Orientation

We began with a synchronous 90-minute Zoom meeting to introduce the participants to one another. We explained the process of FCW that was to come, answered questions, and reviewed the digital platforms that we would be using, specifically Padlet and Edmodo. Padlet is an online idea sharing space akin to a digital corkboard. By double-clicking on the screen or a “plus” button, users can post a digital “post-it” note. Edmodo is a learning management system, with dedicated spaces for threaded multi-media discussion, storage of shared documents, private messaging, and small group discussions. Since our graduate network currently uses Edmodo as one of our online gathering spaces, we created a new, separate group space specifically for the FCW. Subgroups were created within for each of the FCW phases.

Critique Phase

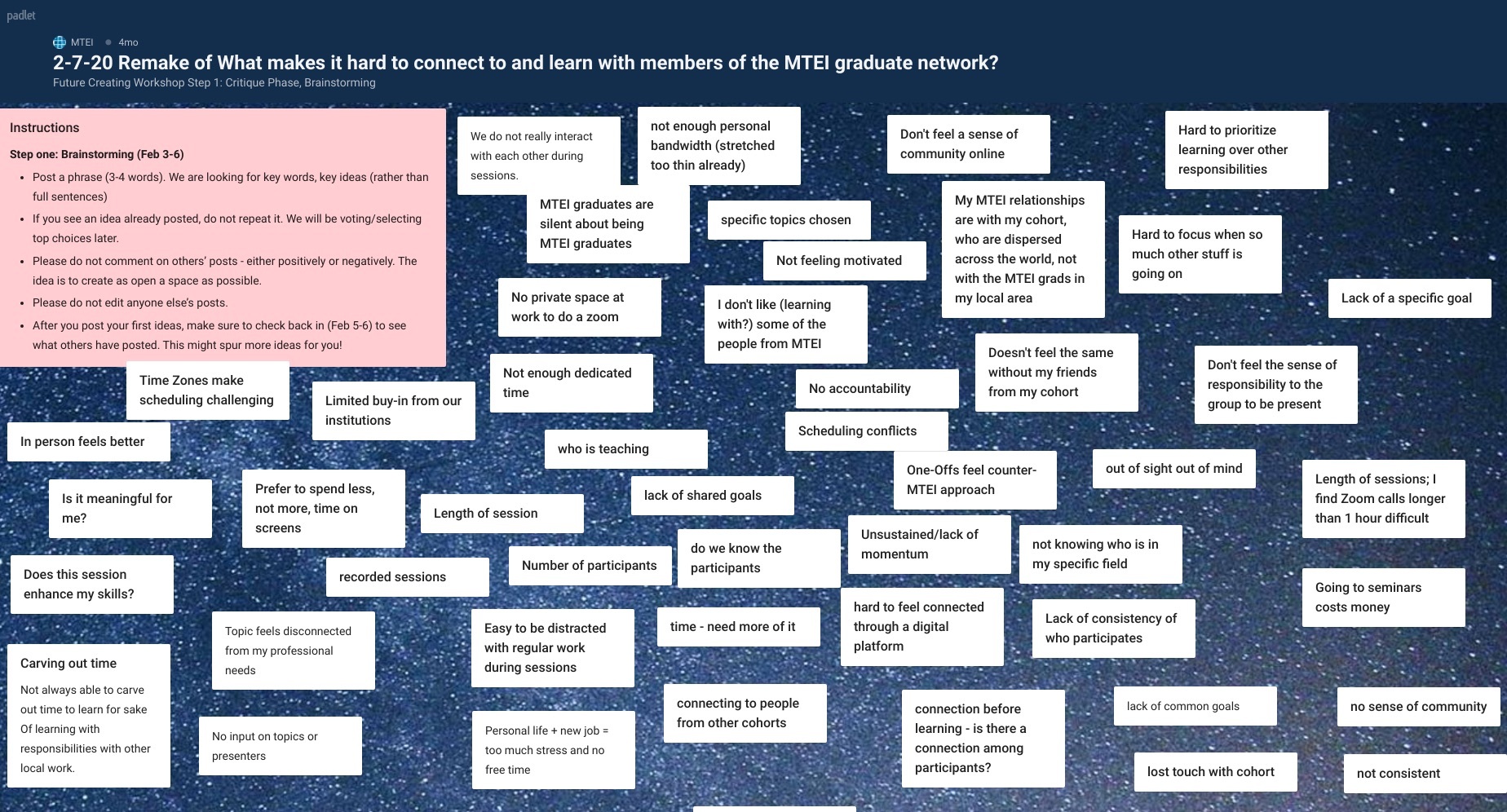

The Critique Phase centered on our focusing question: “What makes it hard to connect to and learn with members of the MTEI graduate network?” This phase had four distinct steps—Brainstorming, Reviewing and More Brainstorming, Voting, Theme-finding/Image Posting.

- Initial brainstorming: Each participant had access to a dedicated Padlet wall, where they were invited to post responses to the focal question. Per FCW guidelines, we asked people to post single words or short phrases in response to the question.

-

Reviewing others’ posts and adding to brainstorming. A few days into the process, we asked people via an Edmodo post to go back to the Padlet to see what others had posted and add any new ideas that might have been inspired by what they read.

-

Voting: Mid-week, we asked participants to vote for 3 posts that resonated most with them. Padlet has a “like” feature, akin to Facebook, which allowed participants to select their three posts.

-

Theme-finding and Image Posting: Toward the end of the first week, we asked each participant to go back to the Padlet and sort the posts (that had received votes) into categories. Once they had done their sorting, we asked them to take a screen shot of the Padlet and post that photo in Edmodo. In keeping with the original FCW process, which often uses silent plays to encourage participants to engage with the reflection process from new perspectives, we wanted to maintain a creative and playful manner for representing insights that might have come up for participants during the critique phase. As such, we asked participants to create or find an image that represented an insight, and to post it together with their theme-finding image. We also invited participants to add a caption or explanation for their image.

We allowed about a week for these four steps and once completed, we moved to the next phase of the process.

Utopian Phase

The Utopian Phase followed the same steps and processes as the Critique Phase (Brainstorming, Reviewing and More Brainstorming, Voting, Theme-finding/Image Posting). We created a new Padlet wall for this phase, together with a new focusing question: If everything is possible, how could you imagine members of the MTEI graduate network connecting and learning? Once again, we allowed about a week for the four phases of the process before moving on to the final step, the Realization Phase.

Realization Phase

While the Critique Phase and Utopian Phase occurred asynchronously, we believed it important to hold the Realization Phase synchronously via Zoom. We wanted to invite a real-time exchange of ideas and the synergy of collective action planning. We therefore devised a different strategy to gather comments, insights, and feedback.

-

Breakout Discussions: When the meeting began, we created two breakout rooms in Zoom, with one group focusing on the Critique Phase and the other focusing on the Utopian phase. Prior to this meeting, we created a new Padlet for each phase, which held all images and the associated captions that participants had created when theme finding. When groups met in the breakout spaces, they were given the Padlet link for their phase group as well as a Google Doc to document their conversation. Both groups participated in a structured discussion protocol to help guide the conversation. The protocol focused on the following questions:

-

What do you see?

-

What questions come up for you?

-

Did anything surprise you and why?

-

Anything missing?

-

What meaning do you make of it?

-

What themes can you identify from these images? (Please try to create three themes.)

-

-

Regroup: When the small groups came back together, they shared the themes they found, and we screen shared the Padlet that each group discussed.

-

Synthesis: We then asked the whole group to consider ways in which the themes from the Critique Phase and the themes from the Utopian Phase related or “spoke” to one another.

-

Action: We then asked the group to consider the following question: What specific actions would bring our utopian theme(s) into reality?

-

Reflection: We closed by asking the participants to take some quiet time on their own to reflect on their own learning. We invited them to respond to three prompts:

-

What’s alive for you now?

-

What did you learn about sustaining and nurturing the MTEI graduate network from this process?

-

What did you learn about sustaining and nurturing the MTEI graduate network in an online space from this process?

-

-

Closing: We thanked the participants and invited them to share their reflective writing with us via email after the meeting.

When the FCW was completed, we had planned to follow up on the action plans with the participants, to continue to take the next steps. However, COVID-19 hit the United States, and all of our energies shifted to focusing on supporting our participants and graduates as well as taking our in-person seminar into online spaces.

Reflection on the Process

Role of Facilitator

As many of us have learned during COVID-19, facilitating groups online is different from face-to-face group work, especially in asynchronous spaces. One important dilemma we confronted was how visible we should be in the Edmodo discussions. We asked ourselves questions such as: How often (if at all) should we post responses to the online discussion? While we wanted participants to feel seen and acknowledged, and we wanted to encourage discussion of the different posts, we also did not want our voices to overpower those of the participants. For example, when participants posted their images with captions in the Critique Phase, Miriam commented on each post to convey that we, as facilitators, were present to the process. Yet, there were fewer participant responses to one another than we had anticipated. Consequently, during the Utopian Phase, Miriam shared this dilemma with the group in the opening post, saying:

Hi all, as we get the theme finding for the Utopian Phase underway… I want to invite you to comment on one another’s theme-finding. I offered comments during the critique phase, and then was concerned that perhaps that stymied your commenting. So, I will restrain myself (!) and encourage you all to respond to one another’s posts. Happy theme-finding!

We found that participants responded more often during the Utopian Phase, underlying the importance of both holding back and also making the invitation to participate more explicit. As we reflected on this facilitation dilemma, we found that the literature on asynchronous learning environments, especially in the Community of Inquiry model, identified this same issue and encouraged “prompt, but modest instructor feedback” (deNoyelles et al., 2014, p. 159). We found this to be an important and delicate balance to maintain.

Technological Considerations

When Mary first shared with us the details of how the FCW process works in an in-person setting, we carefully noted the kinds of interactions that participants had in those spaces. We chose Padlet as our main workspace because it allowed for parallel interactions:

-

Many people could contribute to the same question space at the same time

-

Participants could add as many ideas/posts as they wanted

-

Participants could move and sort posts similar to how sticky notes are used in-person

-

Each phase of the FCW process could be documented and saved for subsequent review

Padlet also afforded some additional benefits. Participants could interact with each other and ideas at any time, regardless of time zone. We were able to intentionally choose background images for our Padlet wall that mirrored the FCW phase (e.g., a starry expanse for the Critique Phase and hot air balloons in an open sky for the Utopian Phase). We used these visuals as another way to invoke the intention behind the phases of the FCW process.

However, Padlet alone did not fulfill all of our connection and interaction goals. We needed a space for asynchronous conversation about the contents of the Padlet wall as well as a video-conferencing platform for our synchronous processing sessions. Edmodo and Zoom fulfilled these roles, respectively. While other learning management and video-conferencing platforms exist, we chose Edmodo and Zoom because they were already in use as part of our network’s communications. Edmodo, in particular, had already been used by both our faculty and graduates to share resources, communicate, and converse—skills that we were using in the FCW as well.

The combination of Padlet, Edmodo and Zoom allowed us to maximize asynchronous and synchronous opportunities to work together. With participants spread across time zones and work contexts, each with a different daily schedule, asynchronous work was essential to reducing barriers for participation. Synchronous work on Zoom at the start and end of the process provided an opportunity to bring real-time collaboration around ideas, an important aspect of the in-person process, into the online space. Clear and thorough pre-FCW communication and an optional Tech Q&A session provided multiple ways to ask and address technical questions.

It is important to note that Internet access is required for all of these platforms to work. The number of Padlets we used in the FCW required a paid Padlet subscription ($99/year as of December 2020), but this was offset by Edmodo being free to use. The Zoom Pro account ($149.90/year as of December 2020) was already a part of our organizational budget. There are a number of other digital tools that provide similar features to Edmodo (e.g., Schoology and Google Classroom) and Zoom (e.g., WebEx and Google Meet). Choosing a tool depends on participants’ familiarity, prior experiences, and comfort levels as well as organizational budget. Padlet’s versatility and flexibility, however, supported this process in unique ways that made the fee well worth the investment.

What’s Come After

To our knowledge, the MTEI FCW was the first time this participatory action research process was attempted online. We learned deeply from this experience and it challenged each of us as action researchers. For MTEI, we will run another iteration of this FCW, focusing on similar questions in the coming months. We anticipate that after months of online work due to COVID-19, the graduates will come with new insights into the question of building learning relationships in online spaces.

Since we conducted the FCW described here, Mary has been involved in facilitating two additional online FCWs. The first was a fully asynchronous process supporting an international climate change education project with partners from Austria, South Africa, and the Philippines. After initial plans for an in-person conference were cancelled in the Spring due to the pandemic, the team decided to use the online FCW process to enable them to continue their collaboration. Given the challenges of working across so many time zones, the ability for participants to contribute when it was most convenient for them made it possible for everyone to be fully engaged in the process.

The second FCW was a part of an on-going participatory evaluation of a social enterprise project in South Gloucestershire, England. Mary has been involved in this project for the past four years, spending a month each summer working with local non-profit organizations in the Southwest of England on an asset-based community development initiative. When the pandemic hit and research plans had to be adapted, Mary and her colleagues decided to use the FCW process to bring together staff members from their partner organizations, members of the Board of Trustees of their funder, the Gloucestershire Gateway Trust, and former members of their community resident research teams to consider what they’d like the future of our communities to look like after the pandemic. In this case, they used a model more similar to the MTEI process combining synchronous and asynchronous elements to maximize participation. Results from this process are currently being used to develop a policy briefing report to further the work of the Trust and to inform local residents of the plans for new initiatives going forward. An additional online FCW is also being planned as part of a local environmental heritage project in Louisville, Kentucky. In this instance, local partners are hoping to incorporate more elements of photography and video to capture experiences of residents with the Ohio River watershed. It is clear that while the online FCW was a useful response to the pandemic, it has the potential to become a permanent and highly adaptable contribution to the action research toolkit going forward.

Conclusion and next steps

Moving participatory action research processes online raises challenges and opportunities for action researchers. By working in synchronous and asynchronous spaces and implementing digital tools to support the adaptability of the process across time and space, we were able to meet practical and philosophical needs of the organization. Taking the FCW online, we found that it was vital to think intentionally about online community creation, opportunities for equity of voice and collaborative access to and analysis of data, and the role of the facilitator. Upon reflection, we understand that we had some significant advantages in terms of the participants’ capacity to access our online spaces. First, the participants had reliable internet access, sufficient bandwidth to participate in synchronous meetings, and consistent access to computers and devices with which they could participate in our research spaces. Second, the participants already had familiarity with Zoom and Edmodo spaces, as these were regular spaces in which our network worked. We are aware, however, that each organization and setting will need to assess these technological considerations in planning and enacting their own versions of FCW.

In taking the FCW online, we needed to adapt core elements of the original process to mirror the practices and philosophy of the method. For example, in the original process, participants post their responses to the focal questions on wall-sized mural paper to invite expansive thinking. For the online process, we used Padlet, which invokes the image of a digital wall. We encourage others who adapt the FCW online to experiment with other modalities of engagement to meet the needs of their organization and/or community.

Many important challenges remain and are ripe for future research. In particular, the facilitation of participatory processes online requires skills, actions, and forms of communication that are different from in-person facilitation. Further, understanding the ways that participants experience the processes online relationally, intellectually, and affectively is vital to the success of these forms of community engagement. While COVID-19 has forced many of us to convene in online spaces, we are also offered the opportunity to learn innovative ways of collaborating across time and space.