Community engagement has long been understood “to encompass the broadest conception of interactions between higher education and community and to promote inclusivity” in a way that “represents broad thinking about collaborations between higher education and the community and intentionally encourages important qualities such as mutuality and reciprocity” (Driscoll, 2009, p. 6). Institutionalizing community engagement is an adaptive challenge (Farner, 2019) that can lead to cultural and organizational change (Holland, 2009) and happens in a myriad of ways (Welch, 2016; Welch & Saltmarsh, 2013). Since the 1990s, higher education leaders, publicly-engaged scholars, and representative associations have advocated for deep, sustained and pervasive community engagement embedded in the academic core of the institution. Such ‘institutionalization’ of community engagement moves us beyond siloed work on the margins of the academic enterprise into the core of an institution’s culture, values, strategic priorities, and operational structures.

Faculty members are responsible for carrying out the core academic mission of the institution through their three primary areas of responsibility: teaching, research, and service. For some faculty who want their work to have broader public purpose and impact, these areas of responsibility grew to include the application of knowledge and the scholarship of engagement to include knowledge generation to address pressing societal problems (Boyer, 1990, 1996). Often an institution’s commitment to community engagement is reflected in its mission, culture and institutional values. In turn institutional values are reflected via policies and practices. Institutional values related to the core of the academic enterprise (teaching, research, service) are primarily evidenced in how an institution recognizes and rewards faculty work through promotion policies and practices which are often articulated via an academic personnel manual. Faculty members are incentivized by promotion policies and often shape their scholarly work accordingly (Pearl, 2015; Ward, 2010). For example, if an institution weighs teaching more heavily than research, or traditional research more heavily than participatory community-engaged research in the evaluation process, this must determine where and how faculty prioritize their time and scholarly work.

Basic scientific research has traditionally been more heavily valued than other forms of scholarly work, but leaders have reformed this over the years. For example, Ernest Boyer served as president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching from 1979 to 1995 and during that time worked with colleagues like Eugene Rice and Russ Edgerton to improve and democratize the academic enterprise broadly and research/scholarship in particular. Boyer’s work on Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate (1990) expanded our framing of faculty work as scholarly work across four areas: the scholarships of discovery, integration, teaching and application where knowledge is “applied” in practice to address real world problems. In 1996, Boyer grew his thinking beyond a uni-directional concept of faculty applying their expertise to social problems to the scholarship of engagement where faculty members partner with community through collaboration and reciprocity, and where both academic and community knowledge and expertise is fully recognized and valued.

Since the late nineties researchers and higher education leaders have continued to broaden our understanding of research beyond basic scientific research to an understanding of faculty scholarship that values partnership, knowledge generation with community (O’Meara & Rice, 2005; Post et al., 2016; Rice, 2016) This community-engaged scholarship requires a “different approach to knowing” (Rice, 2016, p. 31) that is more connected to community, rooted to people and place through strong relationships and a sense of collective responsibility to co-create new knowledge that is used to solve problems and improve lives (Ward, 2010).

Throughout this article, we use several terms to discuss similar approaches scholarly work, including community-engaged, collaborative, and participatory research. While there are important distinctions among these terms, they all share commitments to values like shared power in research through authentic collaboration between academic and community partners (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020; Wallerstein, 2020). Participatory, collaborative, and partnership-based research methods help faculty members achieve their community-engaged scholarly goals, through what can be referred to as collaborative engagement research. One example is community-based participatory research (CBPR) which “[is] an orientation toward research that holds collaboration and equity in participation as core values” (Jacquez et al., 2016, p. 77) where cooperation between traditional and community-engaged research “leads to a holistic research practice grounded in democratic and deliberative values” (p. 77). CBPR is both a pedagogical and inquiry approach that helps both faculty and institutions broaden their understanding of and approaches to community-engaged scholarship. Faculty who integrate research, teaching, and service roles experience high intrinsic motivation as they find their community engagement work to be meaningful, they feel a sense of responsibility for their work, and they see the actual results of their work (Janke & Colbeck, 2008).

While more and more faculty are doing community-engaged scholarly work, and there is increased acceptance of community engagement broadly across higher education in the US, several barriers persist, notably related to promotion and tenure policies (Abes et al., 2002; Ellison & Eatman, 2008; Jacquez, 2014; Janke, Quan, et al., 2023; Sdvizhkov et al., 2022; Weerts & Sandmann, 2010; Wendling, 2023). If, as a field of community-engaged scholarship, we want to continue to center our work in inclusive and participatory methods, it is imperative to recognize and highlight the myriad of ways faculty engage communities as part of carrying out the research, teaching, and/or service mission of higher education. Therefore, in this descriptive research study, we ask: How and in what ways do institutions of higher education recognize and reward community-engaged scholarship? Through our analysis, we examine how institutions define and describe community-engaged scholarship, and identify examples of policies and practices that support engaged scholars.

Literature Review and Framing

The purpose of this study is to describe the policies and practices that colleges and universities have in place to reward and support community-engaged scholarship. The literature that frames our study covers four key areas: 1) recognition and reward of faculty scholarly work, 2) institutionalizing community-engaged scholarship, 3) the role of the Carnegie Elective Classification for Community Engagement, and 4) an overview of institutional case studies that informs the current research.

Recognition and Reward: Promotion and Tenure

Academic rewards systems and promotion and tenure policies serve as a mechanism for recognizing scholarly achievement, protecting academic freedom, and influencing the behavior and choices of scholars (O’Meara, 2011). Because their time and energy resources are limited, faculty members may make the rational choice to focus their efforts on activities that will help them to advance in their careers (Barat & Harvey, 2015). Boyer’s (1990) model of scholarship was a call to reimagine what constituted scholarship and the work of the faculty in response to an increasing emphasis on research productivity. Since then, there have been continued calls to reimagine and reconsider the work of the professoriate, and how that work is assessed (Glassick et al., 1997; O’Meara & Rice, 2005), including through the lens of community engagement (O’Meara, 2005, 2011; Saltmarsh, Giles, et al., 2009).

Institutionalization of Community-Engaged Scholarly Work

There are examples of individual institutions (Ward et al., 2023) and multi-campus studies of institutionalization of community engagement through recognition and reward of engaged research (Abell et al., 2023; Wendling, 2023). The current study advances our understanding through its examination of institutional efforts to recognize and reward community-engaged scholarship across more than 350 campuses and multiple institutional types, across the US. Such a focus is significant given scholars’ increased publicly engaged motivations (Post et al., 2016) and need to know that the academy in general, and their institution in particular, is a place where their values, motivations, and career aspirations can be realized (Ward et al., 2024).

Other scholars have noted the importance of making community engagement central to institutional priorities, including the full academic mission and the promotion and tenure process (Fitzgerald et al., 2012; Holland, 1997; Ward et al., 2023). Due to the importance of effectively documenting faculty work for tenure and promotion reviews (Schimanski & Alperin, 2018), several scholars have developed valuable guidance for the process (Bartel & Forester, 2022; Doberneck, 2016; Doberneck et al., 2010; Doberneck & Carmichael, 2020; Ellison & Eatman, 2008; Franz, 2011). Some of the recommendations from these guides include:

-

Planning early and intentionally for the promotion and tenure process to effectively map engaged scholarly work with institutional and departmental priorities and expectations (Doberneck et al., 2010; Franz, 2011).

-

Seeking guidance on navigating the process from senior scholars and mentors, and developing an expanded peer review network (Ellison & Eatman, 2008; Franz, 2011).

-

Assembling and effectively presenting comprehensive documentation that presents engaged scholarship as having full and equal standing to traditional scholarship (Doberneck, 2016; Doberneck & Carmichael, 2020; Ellison & Eatman, 2008; Franz, 2011).

The Carnegie Elective Classification for Community Engagement

For the past two decades, receipt of the Carnegie Elective Classification for Community Engagement (CE classification) has served as an indicator of institutional commitment to public purpose and community engagement (Saltmarsh & Johnson, 2018). Classified campuses can demonstrate high commitment to community engagement across institutional mission, allocation of resources, the curriculum, and partnerships with broader society. The Carnegie Foundation defines community engagement as the “collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities (local, regional/state, national, global) for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity” (American Council on Education, n.d., para. 1). Of particular importance to this study is the identified purpose of community engagement which is “to enrich scholarship, research, and creative activity; enhance curriculum, teaching, and learning; prepare educated, engaged citizens; strengthen democratic values and civic responsibility; address critical societal issues; and contribute to the public good” (American Council on Education, n.d., para. 1). The purpose makes clear that community engagement, when fully incorporated into the work of an institution, is not a separate mission area, but is rather an approach to the core work of the institution.

In addition to recognizing community engagement in higher education, the CE classification also provides institutions with an opportunity to conduct a thorough self-study that identifies areas for continued improvement (Driscoll, 2008; Saltmarsh & Johnson, 2018; Zuiches, 2008). The CE classification is expressly not a tool used to rank institutions based on their levels of community engagement (Driscoll, 2008; Saltmarsh & Johnson, 2018), but it has played a significant and intentional role in shaping what it means to institutionalize community engagement (Saltmarsh & Johnson, 2020). This has led to somewhat of an isomorphic (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983) tendency to replicate practices and structures that have led to successful classification. We use this framing as an impetus for our research as we identify and describe some of the policies and practices related to community-engaged scholarship that have been recognized by the CE classification. By describing institutional approaches to recognizing and rewarding community-engaged scholarship, we hope to identify models for colleges and universities seeking to institutionalize community engagement more concretely.

When examining and reflecting on the first wave of CE-classified institutions, Saltmarsh, Giles, and colleagues (2009) noted the importance of affecting institution culture and identity by explicitly recognizing community engagement as scholarly work. At the time most institutions primarily recognized community engagement as “service,” but there was momentum building toward clearly defining the parameters of community-engaged scholarship to establish specific criteria for evidence, developing policies that reward community engagement across faculty roles (research, teaching, service), and operationalizing the norms of reciprocity in evaluation criteria, including reconceptualizing what constitutes a publication and who counts as a peer.

Institutional Case Study

The University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNC Greensboro) investigated how community-engaged scholarship was integrated into their institutional promotion and tenure policies (Janke, Jenkins, et al., 2023; Janke, Quan, et al., 2023). This research identified many terms for community-engaged scholarship and varied definitions across university, school, and department levels, with departmental policies, the most influential review level, showing the most variation. While early advances related to community-engaged scholarship into promotion and tenure focused on output and outcomes, this work (Janke, Jenkins, et al., 2023; Janke, Quan, et al., 2023) also identified the importance of defining community-engaged scholarship by its process, including epistemologies, relationships, and building shared knowledge with communities, to legitimize it and support community-engaged scholars.

One of the aims of this case study was to develop a codebook to support the analysis of the promotion and tenure guidelines and the ways that community engagement was integrated into institutional policies (Janke et al., 2022). The codebook was informed by the framework and principles discussed in the Democratic Engagement White Paper (Saltmarsh, Hartley, et al., 2009). The case study research (Janke, Jenkins, et al., 2023; Janke, Quan, et al., 2023) examined UNC Greensboro’s promotion and tenure policies at the university level and in 59 academic departments and seven units (colleges/schools), and the codebook supports analysis of institutional polities and the use of terms across faculty roles of teaching, research/creative activity, and service to signal and address legitimacy of community-engaged scholarship within a larger context of institutional values. The codebook includes the following themes:

-

Terms used to describe community engagement or public-facing scholarship

-

Definitions of terms

-

Policy section in which community engagement-related terms are written (general statement, teaching, research/creative activity, service)

-

Ernest Boyer’s (1990, 1996) categories of scholarship (discovery, integration, teaching and learning, and application) or reference to scholarship of engagement

-

Framing in terms of knowledge integration or creation

-

Peer review references

-

Scholarly impact

-

Scholarship products and artifacts

-

Reference to funding

-

How “rigor” or “quality” is defined

-

References to disciplinary associations

The study concluded that broad university policies need supplemental materials for effective implementation and to support a diverse faculty. Key findings include the proliferation of terms across 67 policies, the frequency of “community-engaged scholarship,” and the significant role of departmental policies in describing the process of CES. The findings from this case study research aim to serve as a resource for scholars in articulating their community-engaged work effectively. By presenting examples of policies and practices from institutions with the CE classification, we hope to highlight methods for acknowledging and valuing community-engaged scholarship. Table 1 provides an overview of how Janke, Jenkins, et al. (2023) define outputs, outcomes, and processes of community engagement that is used as a framework for this study’s data analysis.

The extant literature highlights both the progress and persistent challenges in institutionalizing community-engaged scholarship in higher education, particularly through academic reward systems. Building on this literature, our study offers a descriptive analysis of how CE-classified institutions define, recognize, and reward community-engaged scholarship in their policies and practices.

Methods

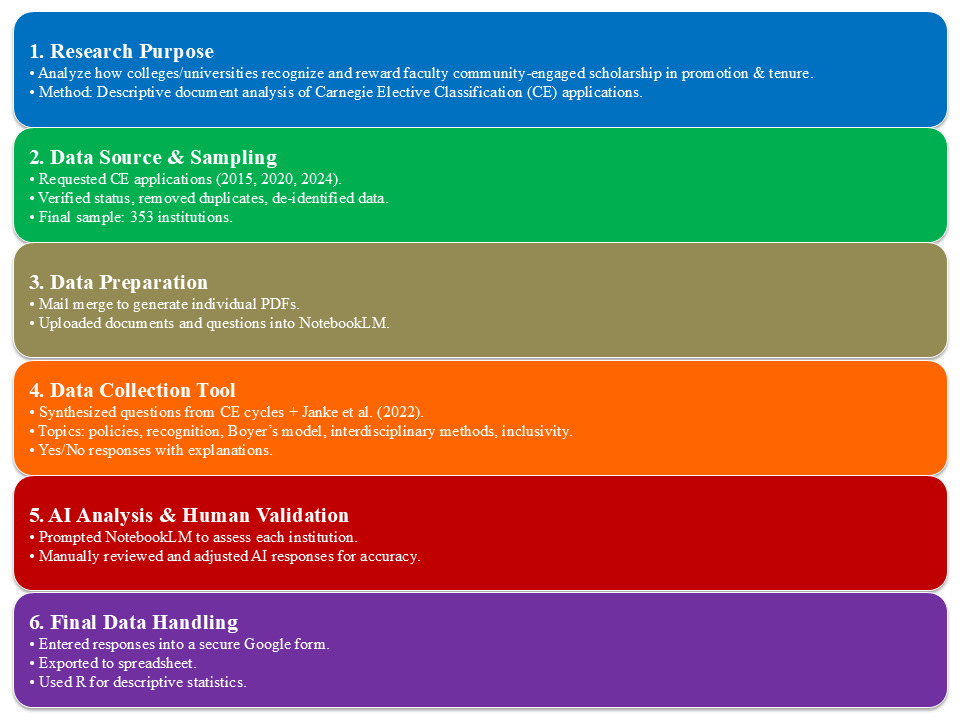

The goal of this research is to describe the different ways that colleges and universities describe how they recognize and reward community-engaged scholarship. The current study is a document analysis of institutional applications for the CE classification, where our primary intent is descriptive, rather than interpretive (Morgan, 2022). Documents can serve a primarily descriptive function when analyzing policies (Karppinen & Moe, 2012), and Owen (2014) notes the particular value of documents (as well as the process of documentation) in higher education policy analysis. In addition to analyzing the information that institutions submitted as a part of their applications, we also used the data to generate basic descriptive statistics related to various elements that appeared in the institutional applications (see discussion of the Data Collection Tool below).

Data

We analyzed institutional applications for the CE classification to understand the overall trend of promotion and tenure policies in the US. While the CE classification has served to legitimize community engagement and affirm its role in the academy, the data that has been collected over the past 20 years is relatively underutilized for research purposes (Pearl et al., 2025). In 2023, the Carnegie Electives Research Lab was established to increase access to and awareness of the CE classification data and facilitate research capacity in the field. As an affiliated research team with the lab, we examine the institutional recognition and reward of community-engaged scholarship, and for this paper, primarily focus on the policies and practices that classified institutions have in place to advance faculty participatory and community-engaged research.

First, a data request was submitted to the American Council on Education, the administrative home for the CE classification for questions that we identified from the first-time and reclassification application frameworks for the 2015, 2020, and 2024 cycles of the CE classification that addressed the recognition and reward of faculty community-engaged scholarship (see Appendix). For each cycle, institutions report evidence from the preceding academic years. For example, institutions awarded the classification for the 2024 cycle reflects data from either the 2018-2019 academic year (pre-COVID) or the 2020-2021 academic year (post-COVID); the 2020 cycle reflects data from the 2017-2018 academic year, and the 2015 cycle reflects data from 2012-2013 academic year. We received the data in spreadsheet files. The first step was to confirm that each institution in our sample received the classification and agreed to be included in the research dataset. We removed any data that did not meet these initial criteria. We also removed duplicate institutions in our sample, retaining the data from the most recent cycle (e.g., institutions that received the classification in 2015 and submitted a reclassification application as a part of the 2024 cycle). For the purposes of our research, we de-identified all institutions in the sample. The final sample included data from 353 colleges and universities. Most of the institutions are public (57.7%), classified as research institutions (56.2%), and grant doctoral degrees (60.6%).

Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Assistance with Data Analysis

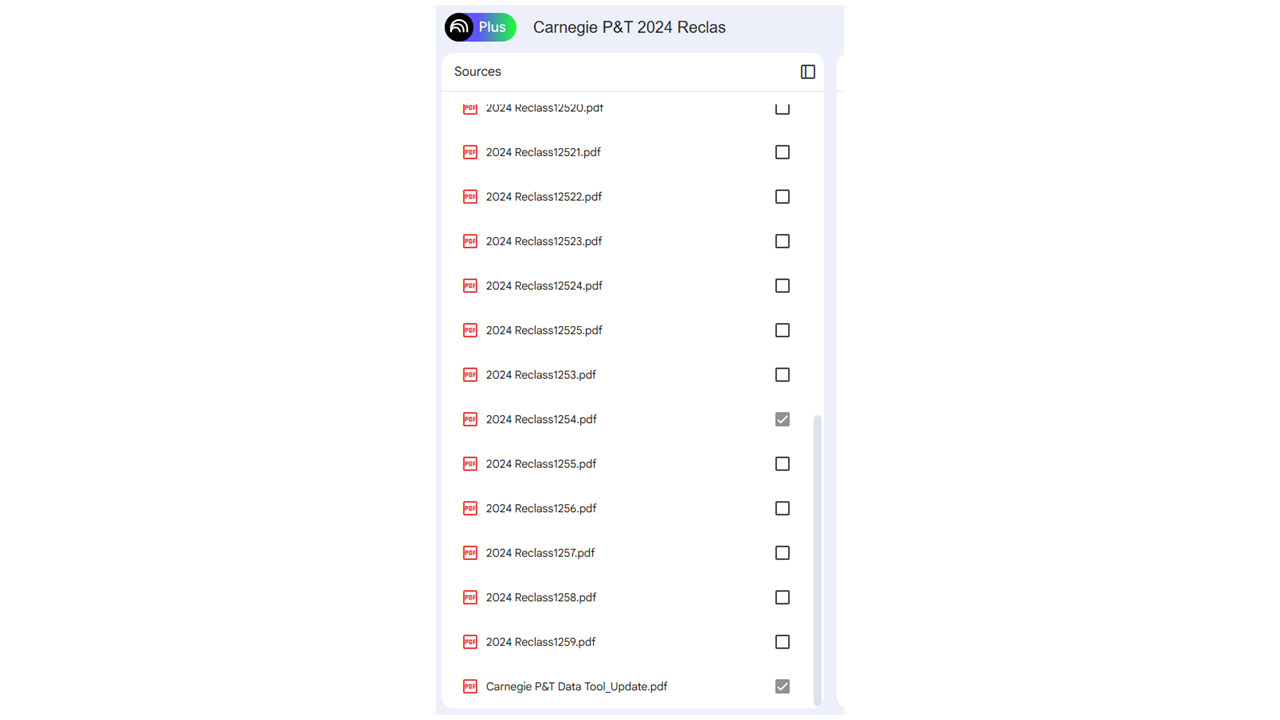

Given the size of our data set, artificial intelligence (AI) tools were utilized to aid our data organization and analysis. The role of AI in qualitative data analysis is still emergent and presents several opportunities and challenges, and requires careful consideration of how prompts are phrased (Siiman et al., 2023). All AI components of our research approach were assistive, and closely monitored throughout. For the purposes of the research, NotebookLM was the tool best-suited to our needs. NotebookLM is a Google Labs research product that has the ability to synthesize and summarize information from multiple sources that are added to a project workspace. The analysis can examine all added sources or individually selected sources. NotebookLM does not share data publicly and is not used to train AI models. The NotebookLM research workspace is password protected and only accessible by the research team, which preserves the confidentiality of institutions in our research sample. The institutional data needed to be converted to a PDF document in order to be compatible with NotebookLM. A mail merge was used, which resulted in the data from each institution being saved into an individual document for analysis, with a unique numerical identifier connected to the cycle for which the application was prepared. All of the institutional documents were uploaded as sources to NotebookLM, along with a separate file with the questions we used for analysis, which was labeled as the Data Collection Tool (see Figure 1).

Data Collection Tool

To analyze and describe the information in the institutional applications, we developed a data collection instrument that consolidated and synthesized questions from each of the classification cycles. The questions primarily focused on faculty roles and rewards, with additional questions informed by Janke et al.'s (2022) codebook. Below, we show the groups of questions used in the final version of the data collection instrument. The response options for each question were either “yes” or “no” using the prompt, “Please use the Data Collection Tool as a rubric to assess the other selected source” for each of the 353 institutions.

Is community engagement in relevant policies, institution-wide?

- Are there campus-wide policies for faculty promotion (and tenure, where applicable) that explicitly review, evaluate, and reward community-engaged scholarly work?

Are policies defined? How is CE described?

-

Has the institution defined “community-engaged scholarship” in its policies?

-

Do the policies define the Outputs (activities, artifacts), Outcomes (purpose, expressed values), or Processes (relationships, epistemology) of community engagement or public facing activities?

- Note: Documentation that defined at least one of the categories (outputs, outcomes, or processes) was considered a “yes” response in our analysis.

-

Is community engagement recognized and rewarded as a form of Teaching and Learning?

-

Is community engagement recognized and rewarded as a form of Research or Creative Activity?

-

Is community engagement recognized and rewarded as a form of Service?

-

Do the policies specifically reference Boyer’s categories of scholarship?

- Note: This included references to Boyer’s model of scholarship as a whole, or individually to the scholarly areas of discovery, teaching, application, integration, or engagement.

-

Do the policies reference any of the following integrative approaches (interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, or transdisciplinary) to scholarship?

Is there recent or ongoing policy change work?

- Has there been recent work (or is there work in progress) to revise promotion and tenure guidelines to better reward community-engaged work?

Data Analysis and Input

The output from NotebookLM included a straightforward response to each question that in most cases was either “yes” or “no.” In some cases (less than 4% of the questions), the response indicated that there was not enough information available to make a determination, or the responses were “likely” yes or no. In these cases, we used the original data to make a final determination. Answers to each question also included a short explanatory paragraph, including footnotes that indicated the section from the source document that were used to make the determination. The output is not unlike the results generated from other qualitative analysis software products, like ATLAS.ti or NVivo, with comparable results (Chen, 2025). For example, NotebookLM also includes detailed annotations in the results that specifically reference back to the source material. Additionally, all of these tools allow a researcher to centralize data for analysis and visualize the data in various forms e.g. charts, word clouds, concept maps for analysis. Where researchers provide NVivo or ATLAS.ti the structure of tags for coding, the researcher provides Notebook LM the structure of a coding document derived from the studies guiding research questions and conceptual framework. This researcher development coding document guides the initial analysis. This initial analysis output was copied and pasted into a separate document for subsequent analysis. This prompt was repeated for each of the 353 institutions in our sample. See Figure 2 for a masked example of NotebookLM output.

As already noted, AI technology is emerging and still experimental. NotebookLM includes a brief disclaimer that its results can be inaccurate and its results should be double checked. Therefore, it was important for our research team to manually recheck and validate each response for trustworthiness, which was aided by the detailed annotations included in the NotebookLM output. Similar to other forms of qualitative research analysis programs (e.g., NVivo and Atlas.ti), reports generated in Notebook LM directly excerpts only from the texts provided and all excerpts are tagged (i.e., are traceable) to the original document. This allows researchers to quickly access the primary document to explore relevant context that may help to provide nuance and assess alignment with the theme or code. We read each of the recommended responses and other output from NotebookLM to make final response determinations for each institution. In a majority of cases (greater than 90%), NotebookLM’s recommended responses were consistent with our analysis. In some cases, however, our interpretations and final decisions differed from NotebookLM’s recommendations. For example, one of the questions in our Data Collection Tool asks whether the document specifically references Boyer’s categories of scholarship. On a few occasions, the default output from NotebookLM would suggest a “yes” response to this question if the information provided in the source “aligns with Boyer’s broader framework” (per the NotebookLM reasoning and justification) but did not explicitly reference Boyer by name. In such cases, the final answer to this question would be “no,” overriding the suggested response from NotebookLM. We entered the final responses for each question into an online, password-protected Google form. The data were then exported into a spreadsheet document to generate descriptive statistics using the R statistical software (R Core Team, 2024). Refer to Figure 3 for a visual flowchart representation of our methodological approach.

Findings

In the following sections, we discuss how the institutional applications in our sample define community-engaged scholarship, demonstrate how community is presented within and across campus policies, and discuss processes of revising the policies. For each section, we include basic descriptive statistics and illustrative examples.

Defining Community-Engaged Scholarship

Many terms were used to describe community-engaged scholarship. These included terms such as, public scholarship, public impact research, civic engagement, as well as community-based research, participatory action research, action research, translational research, collaborative research, advocacy research, empowerment research, and applied research, to name a few of the dozens cited. Beyond the diversity of terms used to describe this type of scholarship within and across institutions, campuses tended to have many ways of describing the scholarship, but few (30%) shared a single, or common campus-definition. Further, many applications did not refer to a campus-wide definition of community-engaged scholarship but rather provided specific examples from departments that had developed a standard definition.

Some institutions (27%) refer to Boyer’s Model of scholarship, in different ways and most often the Scholarship of Application or the Scholarship of Engagement. These references to Boyer tended to be used to explain the variety of types of scholarship, and in particular, the way that community-engaged scholarship seeks relevance beyond the campus or academic community. In some cases, the Scholarship of Application was used to, in a sense, make room for community-engaged scholarship. For example, one institution described Scholarship of Application as “scholarly activities, which seek to relate the knowledge in one’s field to the affairs of society. Such scholarship moves toward engagement with the community beyond academia in a variety of ways, such as by using social problems as the agenda for scholarly investigation, drawing upon existing knowledge to craft solutions to social problems, or making information or ideas accessible to the public.” Other campuses used Boyer’s later work developing the Scholarship of Engagement, referenced by one campus to point to the mutually beneficial nature of engagement (i.e., it meets both academic and community needs and interests).

Still referencing Boyer’s model, several applications emphasize the importance of the Scholarship of Integration. One institution defines this approach as “critical evaluation, synthesis, analysis, or interpretation of the research or creative work produced by others; it is often interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary in nature,” and specifies how faculty members incorporate this language into their annual reviews and dossiers. Other applications discuss the inherent link between community-engaged scholarship and an integrative view of scholarship. For example, a departmental example highlights “cross-disciplinarity, connected learning, and community engagement.” Another example notes that “inter- and multi-disciplinarity and collaboration are often essential to understanding complex problems.”

Outputs, Outcomes, and Processes of Community-Engaged Scholarship

While many institutions did not provide succinct definitions of community-engaged scholarship, a large majority (89.5%) provided examples of outputs, outcomes, and/or processes related to community-engaged scholarship. As mentioned above (Janke, Jenkins, et al., 2023), community engagement community engagement outputs are products, activities, or artifacts that are produced, delivered, or supplied. Community engagement outcomes are described by purpose, expected or achieved contributions, or values. Processes related to community engagement are relationships, the ways in which partners work together, epistemic approaches, or the role of community members in the co-construction of and sharing of knowledge.

Outputs. The examples of outputs throughout the application in our sample were wide-ranging from traditional activities and artifacts, such as articles written for academic, peer-reviewed journals, presentations made at academic conferences, or invited talks. Other policies expanded examples more broadly, particularly in pursuit of nonacademic audiences, such as governments, nonprofits, and communities. These included activities and artifacts such as articles and essays in professional journals, and publications read by community members, technical reports, policy papers, presentations, reports compiling and analyzing community program outcomes that lead to action plans, or reports prepared for government and non-governmental agencies, as well as developing educational materials, instructional tools, workshops, and continuing education and off-campus or outreach teaching. The creative arts are also represented in applications, including public art projects coordinated with a public entity or government, the creation of a public performance involving community constituents, public history exhibitions or documentaries, or other public performances.

Others referred to serving as a board member or in other leadership roles for community organizations, professional groups, or governmental agencies. Outputs also include working with students, including developing community-engaged learning courses or curricula or supervising student community-engaged research.

Outcomes. Some thematic outcomes include addressing societal needs and problems, enhancing community well-being and quality of life, achieving social change and public good, fulfilling institutional mission and values, building and strengthening partnerships, impacting disciplines, and bridging theory and practice. Some examples include explicit reference to scholarship that “contributes to the public good,” “yields artifacts of public and intellectual value,” addresses “larger societal problems,” or centers “public issues such as advancing human and environmental health, enhancing educational opportunities, and promoting social, cultural, and economic development.” Another application mentioned impacting institutional culture as an outcome, and identified community-engaged scholarship as a way to “enhance the scholarly life of the university or the discipline, improve the quality of life or society, or promote the general welfare of the institution, the community, the state, the nation, or international community.” Slightly more than half of the applications noted the ability of community-engaged scholarship to advance the institutional reputation and to sustain partnerships and relationships with policymakers and legislators.

Community engagement was also identified as a pathway for promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion and addressing the needs of specific communities. Policies explicitly value contributions that promote diversity and equal opportunity, including efforts to advance equitable access to education, public service that addresses the needs of diverse populations, or research that is responsive to historic inequalities. One example specifically affirms research and scholarship requested by Indigenous communities in fulfillment of expectations for scholarship, especially research “utilized by Native American communities to support their nation-building and self-determination efforts.”

Processes. For our research, we considered processes to be inclusive of approaches to relationships and partnerships, and epistemic approaches to knowledge generation (Janke, Jenkins, et al., 2023). As an example, and evocative of the fundamental assumptions of community engagement, one application referred to the fact that engaged scholarship “should involve a partnership with the public and/or private sector,” while another talked about the process of fostering an institutional culture in which community engagement emphasizes the democratic, deliberative, and co-creative aspects of scholarly work. The processes discussed in multiple applications also focused on the process of disseminating the results of engaged scholarly work that both meet the criteria for traditional academic rigor, but are also accessible to audiences beyond the academy.

The process of collaboration and an ethos of partnership was mentioned multiple times in the context of faculty and staff colleagues, students, practitioners, and community partners to work toward addressing local and regional needs. Several applications also mentioned processes related to evaluation and assessment, some specifically elevating the concept of expanding who is considered a peer during the review process. Other applications pointed to practices like the development of detailed evaluation criteria and performance standards that are informed by community partners, the intentional elevation of community-based scholarship, and formal recognitions for excellence in community-engaged scholarship.

Integrating Scholarship into Teaching, Research, and Service

In our sample, an overwhelming majority of institutions were able to identify examples of how Teaching and Learning (90.4%), Research and Creative Activity (90.7%), and Service (96.9%) were recognized and rewarded as forms of community-engaged scholarly work. In most cases, institutions provided examples of how community engagement was an acceptable approach in all three areas; however, there are some notable exceptions. For example, one institution identified that traditionally, community-engaged scholarship had qualified only as service. When they revised their policies, however, community-engaged scholarship was connected to teaching and research, but no longer to service. Some examples also described work that had been done to advance community-engaged scholarship’s integration into either teaching or research, but a relative lack of progress in the other area. Finally, while a large majority (nearly 80%) of applications pointed toward policies that reward community-engaged scholarship, some institutions also chose to include examples of internal recognitions and awards that recognize excellence in community-engaged scholarship as evidence of rewarding these approaches.

From a teaching and learning perspective, community-engaged scholarship was specifically identified as service-learning, community-based learning, community-engaged learning, experiential learning, and applied learning, to name a few examples. Multiple applications cited policies that reward “innovative” teaching approaches as evidence of support for community-engaged teaching and learning. Community-engaged internships and practica were also cited, as were courses that primarily focused on civic engagement and development. Some applications also mentioned supervising students in community-engaged research as a pedagogical approach, while other applications consider this type of work as research. As mentioned above, there are a large number of traditional research outputs and methodological processes that reflect community-engaged scholarship in the applications in our sample. Some examples provided indicate that community-engaged scholarship is acceptable when the work meets generally accepted criteria for scholarship, or are disseminated through disciplinary publication and presentation outlets. Other applications demonstrate a more expansive view of what qualifies as research and creative activity.

Service is the category to which community engagement has traditionally been most readily connected, and some institutions still specifically cite community-engaged scholarship only as a form of service, while others are more specific as to which components of community engagement connect to service, and which connect to teaching and research. Some of these examples include leveraging academic expertise for leadership in community-based organizations or providing technical support and guidance. Finally, there are some examples that acknowledge how community-engaged scholarship is a synergistic and integrative approach in which teaching and learning, research and creative work, and service are interwoven.

Community-Engaged Scholarship Within and Across Campus Policies

In total, 272 of the 353 institutions (77.1%) provided evidence of policies where community-engaged scholarship was included. Some institutions used explicit language in their promotion, tenure, and other reward policies that articulate an expectation of engaged scholarship, or as one institution states, “utilizing relevant research by linking theory and practice in collaboration with community stakeholders to solve pressing social, civic, or ethical problems.” Some applications included language related to service (sometimes specifically community service) in annual evaluations as evidence of campus-wide reward policies for community engagement. Other applications referenced system-wide policies that reward community engagement that were applicable to individual institutions within the system. One way of distinguishing between approaches to rewarding engaged scholarship is the difference between “expected” approaches and “accepted” approaches. Some institutions included language about specific expectations of effort dedicated to engagement, while others refer to an “inclusive view of scholarship” that includes community-engaged approaches, or that “public engagement” and related approaches to scholarship “should be considered when applicable.”

For applications that were unable to provide clear evidence of campus policies, the information provided in the responses often spoke to specific contextual circumstances. For example, one community college indicated that there was a system- and state-wide union contract in place that prevented an institutional policy related to community engagement. Despite the inability to formalize policy, that institution’s application does indicate several practices that signal strong campus-wide support for community engagement.

Revising Policies

Reflective of the rapidly changing environment for community engagement, 79% of institutions in our sample indicated that they were in the process of revising their guidelines to better reward community-engaged scholarship, or had recently done so, including 81% of the institutions that indicated that they did not currently have institution-wide policies in place. Some institutions indicated that their faculty senates were actively (or had recently) engaged in the process of formally recognizing community-engaged scholarship. Some of these changes were incremental and generally involved small language shifts, while others described their revisions as an overhaul. Other institutions mentioned that the revisions were being instigated at the behest of executive leadership at the institution, most often the provost. This approach represented a more centralized approach, while others were more decentralized in the process of revision, with initial changes coming at the unit or departmental level. A few institutions cited their work preparing for the Community Engagement Classification as the impetus for enacting change, and many institutions seeking reclassification indicated that faculty rewards were a specific focus after their initial classification.

Discussion

Our research aimed to illustrate how higher education institutions articulate their methods for recognizing and incentivizing community-engaged scholarship. Institutional policies are crucial for effective implementation (Janke, Jenkins, et al., 2023; Janke, Quan, et al., 2023), and the examples we provide can guide institutions seeking to foster community-engaged scholarship on their campuses, which can serve as a valuable step for broader institutionalization of community engagement.

Our findings show that community-engaged scholarship is prevalent in higher education. For institutions that are working to revise their promotion and tenure policies to be more supportive of community-engaged scholarship, there are qualities that have consistently been present in institutions that hold the CE classification. For example, a large number of institutions were able to cite clear policies that explicitly review, evaluate, and reward community-engaged scholarly work. However, far fewer campuses have an explicit definition of community-engaged scholarship, which suggests there may be a lack of shared language around the practices. On one hand, this discrepancy could be attributed to a desire to account for multiple disciplinary norms about what constitutes community-engaged scholarship, but a lack of consistent definitional understanding for community-engaged scholarship, specifically, could also be an indicator of inconsistent institutional culture adoption.

Alternatively, the absence of a single commonly used term or the precise definition of community engagement may be strategically helpful in order to organize policy change in promotion, tenure, and reappointment documents in that it allows for a broad understanding of what it means, and hence broad buy-in (Janke, Jenkins, et al., 2023). While the inclusion of community engagement terms in policy is essential for creating a foothold for community engagement to be recognized and rewarded, additional effort may be needed to ensure that the original intentions that motivated the change are, in fact, effectively operationalized. If the transformative aspects of including community members as full collaborators and thought partners in scholarship is to be actualized, then core aspects of the definition, reciprocity and mutual benefit, must be recognized and rewarded in practice (Janke, Quan, et al., 2023). Hence, the adoption and operationalization of the core tenets of community engagement may require a step-wise approach of first, establishing broad buy-in through a broad understanding in order to adopt language in policy, and then later supporting documents, policies, and professional development to support understanding regarding essential processes, outputs, and outcomes. In other areas of the application, community engagement (broadly) and community-engaged approaches to pedagogy are defined, but not often community-engaged scholarship. Institutions have been able to connect definitions of community engagement to their particular institutional mission and culture (Quito et al., 2024), in part, because there is a question to this effect that is specifically asked in the classification framework. This suggests there may be value in future CE classification cycles to specifically ask institutions to adopt a university wide definition for community-engaged scholarship.

Despite this lack of definitional consistency, institutions regularly articulate examples of outputs, outcomes, and processes, and demonstrate how community engagement has been integrated into teaching and learning, research and creative activity, and service. Making explicit the ways community-engaged scholarship manifests the tendency to default to traditional approaches to scholarship in the absence of concrete examples (Alperin et al., 2019; Janke, Jenkins, et al., 2023; Janke, Quan, et al., 2023). Identifying the various institutional supports that scaffold community-engaged scholarship in support of promotion and tenure also reinforces its integration across research, teaching, and service (Rios & Saco, 2025).

For faculty members who use participatory methods, we believe that the outputs, outcomes, and processes identified through our analysis may be informative as they document their community-engaged work for review as review committees can struggle in the evaluation and categorization of community-engaged scholarship (Wendling, 2023). Having a menu of options that represent engaged scholarly approaches provides faculty members with a starting point from which to adapt language that can speak to their particular institutional and departmental values. Moreover, because the CE classification frameworks specifically ask questions in these areas (see Appendix), it is not surprising that these areas were largely able to be answered in the affirmative, especially for institutions that earned the CE classification. However, it is evident that, at least to some degree, institutions have been thoughtful and purposeful about the connections between community engagement and domains of scholarship.

It is important to recognize that policies in the absence of application do no good. Policies that support community-engaged scholarship are only good if they are fully utilized by faculty and administrators alike. They are vital for faculty to point to in preparation for merit and promotion actions, especially as a safeguard when departmental colleagues or academic personnel review committees know little about or dismiss this form of scholarship. Likewise, policies provide a guide for review committees to objectively evaluate faculty contributions in the areas of research, teaching, and/or service. Therefore, it is important for executive leadership to make explicit the value of community-engaged scholarship during faculty and department chair orientations, annual calls for merit and promotion actions, and the myriad of awards and prizes that recognize excellence.

While we believe that our findings provide valuable examples of support for community-engaged scholarship, we also want to acknowledge that community engagement can, and should, be responsive to particular institutional and community cultures. Acknowledging and celebrating a singular, homogenous approach to community engagement is bound to overlook approaches that may deviate from the standards advanced by Carnegie, but are equally impactful and meaningful.

Our work highlights the need for continuous dialogue on campuses and within the engaged scholarship field about institutionally defining community-engaged scholarship and developing a shared framework that accounts for different contexts. It is essential that as community-engaged scholarship becomes more embedded in our institutions, we do not become complacent and neglect to address the systemic inequities within higher education reward systems that impact community-engaged scholarship.

Methodological Contribution

While the primary focus of this article is the description of the reward recognition of community-engaged scholarship at CE-classified institutions, we hope that our methodological approach can also be instructive to both researchers and practitioners. Artificial intelligence (AI) is still in its relatively nascent stages, but we believe it can be a useful research tool when utilized responsibly. We did not use AI as a replacement for our own insight and experience, but largely as a way to help organize our data to allow for more efficient analyses. We also want to emphasize the importance of transparency when using AI tools for research and scholarship, which helps to demonstrate trustworthiness and allows for repeatability.

Directions for Future Research

Building from the initial results of this study, our ongoing research collaboration will shift from descriptive to interpretative analyses of promotion and tenure components of the Carnegie CE applications. In addition to the application framework questions that were examined in this study, there are other relevant questions to be explored and unpacked, including policies for different career tracks and at different organizational levels, including where changes are taking place. As discussed above, 79% of institutions in our sample indicated that they had recently, or were in the process of revising their policies. Continued analyses can offer additional insight into the places from which these changes tend to come most consistently (e.g., executive leadership, faculty senate). We are also in the process of developing a typology of policies and supports for community-engaged scholarship using latent class analysis (Collins & Lanza, 2010). Having a typology of policies will provide additional insight into institutional strategies to support community-engaged scholarship.

As discussed earlier, our research is affiliated with the Carnegie Elective Classifications Research Lab. Several of our collaborators in this work are currently examining questions related to the varied ways that community engagement shows up across different contexts and institutional types (Pearl et al., 2025). For example, future research should examine the important variations in policy language across Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Hispanic-serving institutions, community colleges, or religiously affiliated institutions present valuable avenues for continued exploration and analysis.

The 2024 CE classification cycle included a new question that asked about how institutional recognition and rewards policies account for the “often-racialized nature of community engagement”. Many applications discussed the connections between their community engagement mission and diversity, equity, and inclusion, but only a small percentage of institutions in our sample (5.4%) provided information that explicitly connected to promotion and tenure policies. It is increasingly important to intentionally examine how institutions acknowledge that community engagement work often occurs in white racialized spaces and systems that perpetuate racial oppression, and that BIPOC faculty, staff, and students often feel their service contributions to communities of color are important but not valued or recognized by the institution. This avenue for future research is increasingly relevant in a political environment that includes words like “community” among those no longer deemed acceptable to the Federal government (Connelly, 2025). As discussed earlier, the data from the institutions in our sample pre-date many of the federal policy shifts; therefore, we believe the data from the 2026 cycle (in review as of this writing) will be particularly informative.

Limitations

An important limitation of this study is that we have self-reported data examining how institutions choose to represent themselves in their applications for the CE classification. Institutions provide evidence of best practices and how community engagement is socialized and practiced widely at their institution. While this information can serve as an important indicator, these data are all self-reported and are designed to frame the institutions positively to earn the CE classification; therefore, it may be difficult to discern institutional culture from these documents alone without any other forms of data collection. Our findings do not provide insight into the effectiveness of these policies, the experiences of faculty members from different backgrounds as they progress through their careers, or insight into the process of how policies have evolved and developed over time.

In addition, we only examined a select subset of questions from the applications, and were therefore unable to determine the degree to which the practices described in the questions in our dataset were consistent throughout the full applications, or if additional evidence in line with our research purpose was present in other sections of the application. We recognize that not all institutions who are deeply engaged with their communities hold the CE classification, therefore selection bias may have affected our findings. For any number of reasons, some institutions with exemplary policies and practices to support engaged scholarship may not have received the Classification after applying. Further, the process of applying is resource and labor-intensive, so many institutions may have elected not to apply.

Finally, we acknowledge that there are some inherent limitations to our use of NotebookLM as an assistive tool. While we took several steps to maintain the integrity of the research process, artificial intelligence tools are a new and rapidly shifting technology. NotebookLM, in particular, is not designed for academic qualitative data analysis like tools such as NVivo or Atlas.ti. Because of this, the frequency of some elements in our data (i.e., the number of applications that specifically reference public policymakers or legislators) were estimates rather than exact counts.

Conclusion

Community engagement as scholarly work in colleges and universities is increasingly relevant in higher education, necessitating careful consideration of how institutions intentionally support, reward, and recognize participatory, collaborative research. In this descriptive study, we analyzed promotion and tenure related data from the applications from 353 institutions that received Carnegie’s CE classification. Through this research, we have identified strategies for how community engagement has been integrated into teaching, research, and service, and examples of outputs, outcomes, and processes of community-engaged scholarship. We have also identified areas for continued institutional growth, like developing specific campus-wide definitions of community-engaged scholarship that complement existing definitions of community engagement. We also acknowledge that while policies and practices are important and necessary, they are insufficient if they are not supported by changes to institutional culture and climate. We believe that this study lays the foundation for additional studies of these data and interpretative analyses that further explore how and the degrees to which community-engaged scholarship is recognized and rewarded in higher education.

.png)

.png)