Introduction

Equitable peer assessment of faculty productivity is hindered by unexamined institutional values and practices that systemically discount community-engaged scholarship. Community-engaged scholarship (CES) is defined as a highly interactive, time-intensive, relationship-oriented approach to collaboratively working with communities to research areas of critical importance to that community (e.g., Austin, 2021; Collins et al., 2018; Marrone et al., 2022; Vangeepuram et al., 2023). Unlike “traditional” discovery forms of research, in CES, decision making is collaborative, and data and dissemination are co-generated. The outcomes are often long-term in nature, can be intangible, and ideally create significant positive changes to the community of interest (e.g., Hyland & Bennett, 2013; Rink et al., 2020; Salimi et al., 2012). Indeed, CES “makes scholarship meaningful by ensuring it is directly and immediately useful for community ends” (Kajner, 2015). Whereas peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations can and do result from community-engaged scholarship, often the primary outcomes are more holistic in scope and may not result in “peer reviewed” products. For example, this can include the construction of new processes or policies, building trust in a community program, or participation in an important activity. Other examples include toolkits and reports, website and social media development, as well as innovative coursework, curriculum, and programs. Community engaged scholarship makes a big impact, but how to measure that impact often perplexes university evaluation committees who are more accustomed to more easily quantifiable metrics.

Traditional discovery research metrics often include citation counts, impact scores of the journal, authorship order of the article, the h-index, the publication press, etc. (e.g. Hirsch, 2005; Kumar, 2009). Such metrics disadvantage community-engaged scholars (e.g., Austin, 2021; Blanchard & Furco, 2021; O’Meara, 2016). CES is often touted as important by the university, but also undermined by faculty evaluation processes that do not recognize, regard, and reward CES (Bell & Lewis, 2023; Gelmon et al., 2013; Robinson & Hawthorne, 2018).

Given the liminal status of CES in many universities, our work leverages the Boyer Model (Boyer, 1990; Boyer et al., 2015) of scholarship reconsidered to expand the narrow view of scholarship to a more holistic “scholarship of engagement” that can be embedded within faculty promotion criteria and processes. Our participatory research methods (PRM) allowed for expanding the definitions of scholarship to include CES and our co-created results present concrete ways for community-engaged scholars to be rewarded and regarded in the full professor promotion process.

Starting with the full promotion process was a deliberate decision. While overhauling the entire promotion and tenure process is the ultimate goal, starting with one point in the process is an important part of our PRM to build trust, demonstrate feasibility, and create tangible successes that lay the groundwork for future scalable changes (e.g., Jagosh et al., 2012). Moreover, within academic equity work, there is often more attention on tenure processes and less attention to the move from associate to full professor, with some declaring a “dearth of scholarship on the topic of advancement to full professor positions” (Freeman et al., 2020, p. 2). Unlike tenure and promotion to associate professor, promotion to full professor is voluntary and not typically on a specific timeline, rendering clarity in process and policy critically important (Britton, 2010). Promotion to full professor often affords institutional influence and signals full membership in the academy (Britton, 2010) and, as such, our goal was to focus on pathways to reward and regard CES at the promotion to full professor stage of career progression.

Context

The university is a mid-sized R2 institution in the Mountain West. It is the smallest of four campuses in a system of public institutions and is the only research university serving the southern portion of the state. It is comprised of six colleges, as well as the Library and the Graduate School, serving approximately 11,000 undergraduate students. As of fall 2024, there were approximately 500 faculty with 288 of these being tenured or tenure-track faculty members (women-identified = 130, men-identified = 157, 66% white). There was an even distribution of assistant (n=97), associate (n=97), and full professors (n=94). The institution is a rising Hispanic-serving institution, though the tenured and tenure-track faculty make-up is still predominately white as of 2023 (white = 78% vs. Faculty of color = 22%).

Participatory Research Methods

Over the course of one year, we created multiple spaces for faculty and administrators to discuss Boyer’s (1990) conceptualization of multiple forms of scholarship, with a particular focus on the “scholarship of engagement.” As Boyer writes “the scholarship of engagement means connecting the rich resources of the university to our most pressing social, civic and ethical problems, to our children, to our schools, to our teachers and to our cities.” (p. 6). We also drew upon the updated and expanded vision of Boyer’s conceptualization to further articulate the “priorities of the professoriate” (Boyer et al., 2015).

The goal was to create sense-making and sense-giving opportunities (Kezar & Eckel, 2002) to define terms, grapple with traditional measures and metrics of faculty promotion criteria, and discuss the alignment of CES with the university mission, values, and faculty work within every college on campus. Unit criteria for reappointment, promotion, and tenure, while adhering to the Board of Regent policy, are unique to campus units. Faculty within each unit at this institution serve as the primary creators of criteria. Thus, it was vital to the success of this reimagining and expansion of promotion criteria to garner support from many constituents, including faculty and administrators from different units on campus. Note that because our project focused on the full professor promotion process primarily, we intentionally reached out to those individuals with more social and political capital to invest in and lead transformational change at the institution. We also included a few CES scholars early in their careers to draw on their expertise and engage them as potential change agents in possible efforts to reshape the tenure process in the future. We leveraged the unique perspectives and knowledge of both administrators and faculty to create a holistic picture of where promotion evaluation structures are currently and how they hoped to reshape them for the future.

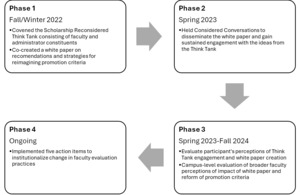

The project unfolded in four phases. First, we brought together a think tank with the aim to co-create a white paper (Phase One). We then engaged in considered conversations with additional constituents and to ensure wide engagement with the white paper (Phase Two). Next, we did a “member check” with the participants to measure their level of engagement and the success of our think tank, as well as an overall faculty evaluation to gauge campus sentiment regarding the concepts and processes outlined in the white paper (Phase Three). Lastly, we implemented some of the strategies proposed by the white paper to institutionalize some of the transformational changes (Phase Four).

Throughout the project, we used the West Virgina University ADVANCE “Dialogues” technique, which draws upon facilitation strategies that gains trust, creates multiple participation opportunities to ensure input is heard and incorporated, and generates collective self-efficacy (e.g., Jackson et al., 2023; Latimer et al., 2014). This approach to institutional transformation engages PRM to create a multi-dimensional model of organizational change. Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram/timeline of the four phases of the project.

Phase One: The Scholarship Reconsidered Think Tank and White Paper

In Phase One of the project, we engaged community members in a think tank with the goal of creating co-learning opportunities, build on the strength of multiple perspectives, and generate a shared document for broad dissemination (similar to PRM strategies outlined by Gunn et al., 2022).

Community Partners. To identify think tank members, our team began by brainstorming promising change agents from each college on campus representing a range of faculty ranks and disciplines. Each identified person was individually contacted via email with a nomination letter requesting their participation in the Scholarship Reconsidered Think Tank. We also sent an open invitation to the faculty listserv requesting any self- or other nominations from interested faculty. In total, 21 faculty (67% women-identified, 76% white, 9.5% Asian, 14.5% BIPOC) ranging from assistant professors (19%), associate professors (29%), full professors (48%) and two associate deans participated. Of these participants, 33% were from a STEM discipline. This process allowed us to build a self-motivated and engaged pool of faculty prepared to critically examine existing faculty evaluation structures over the course of the following year in the think tank. The 21-person faculty think tank committed to meeting three times over the fall term to discuss assigned readings, engage in critical conversations around faculty evaluation policies, and strategize how to reimagine the promotion to full professor process on our campus in ways that broaden the definitions of scholarship (see Appendix A for Think Tank Syllabus). Each participant was provided with a physical copy of Boyer’s (1990) Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate, We modeled sessions like graduate-style seminars where participants were encouraged to deeply engage with the readings and critically examine assumptions about faculty evaluation practices; challenging often outdated and implicitly biased forms of recognition and regard for faculty work. These sessions culminated in the co-creation of a white paper outlining strategies and recommendations for campus to employ in the near and long term (described later). The sessions were organized as follows:

First Session. The faculty were oriented to reconsidering scholarship evaluation in a co-hosted session with a national expert on the topic. They were asked to consider the following thought question,

“A significant barrier to advancement for women and faculty of color is disproportionate engagement in the activities that contribute directly to the vibrancy of higher education, but which do not count toward promotion. What are some of the consequences of discounting this “hidden work”? For women and faculty of color? For student success? For the role of the university in a democratic society?”.

The resulting discussion allowed each participant to share their experience with faculty promotion and concerns they have about making changes to this long-standing process. This session set the stage for intentional, participatory work of the next two sessions and the creation of the white paper.

Second Session. We facilitated think tank participatory engagement in a brainstorming session centered on the opportunities and barriers of reconsidering scholarship, which in turn led to a deep conversation about what counts for promotion to full professor. We began the conversation with a thought prompt and discussion related to Boyer et al’s (p. 111) argument that it is “in graduate education where professional attitudes and values of the professoriate are most firmly shaped.” We asked the participants to do a write-pair-share activity to explore how their own graduate experience defined their views of scholarship. This helped us further explore the biases that might be influencing our definitions of scholarship and also helped build empathy and trust amongst participants. We then turned to an engagement strategy involving each participant individually listing possible positive and negative outcomes of making this shift in faculty evaluations. Each participant then read aloud their lists to the group to ensure each voice was heard and that opposing and creative viewpoints were also discussed and incorporated into notes. Duplicate positive and negative outcomes listed by multiple participants were removed from the final list generated by the think tank. To encourage a positive and joyful environment, this portion was gamified, with those having the highest number of unique positive and negative outcomes winning a small prize (e.g., socks). The think tank was then broken into smaller working groups to thematically organize the generated list of pros and cons. This helped to distill the essential elements of the arguments for and against reimagining faculty promotion processes. This also allowed the community partners an opportunity to anticipate and begin addressing pushback from the larger campus community that might occur when fundamental and entrenched promotion traditions of the academy are expanded.

Third (and Final) Session. Here, the think tank members developed both short- and long-term strategies needed to begin shifting how faculty are evaluated on their CES during full professor review. In honor of this final meeting, we playfully acted out the “ground rules” for the session (e.g., by having two participants exaggerate not paying attention for comical effect) and asked participants to put a sticker on which motivational quote from a pop culture icon most resonated with them (e.g., Dolly Parton’s quote “If you don’t like the road you’re walking, start paving another one.”). Then, in smaller working groups within the think tank, the participants wrestled with the pros and cons generated in the prior session and developed creative ways to address the barriers and highlighting possibilities. This final session ended with an awards ceremony where participants received a leadership recognition certificate as well as an (unexpected) $125 gift card to local small businesses for their work in the think tank.

White Paper Co-Creation. While the formal meetings of the think tank concluded, the partnership continued after that final session. Using a shared file system, think tank members next co-created the “Scholarship Reconsidered” white paper over the course of the next two months. In small groups (3-4 people), participants volunteered for various sections of the draft based on their personal interests in the think tank discussions. They reviewed the notes from the think tank sessions and co-wrote sections of the white paper based on what they learned during those collaborative seminars. The goal was to allow for a cyclical and iterative process of engagement (e.g., Gunn et al., 2022). All partners also volunteered to work on paper logistics, which included tasks like creating the paper template, merging and formatting sections, editing, and final proofreading. In this way, we ensured that everyone reviewed the final product before dissemination. Still, this meant that the paper represents the complexities (and sometimes repetition and contradictions) inherent in collective work.

White Paper Contents. The Think Tank co-created a 56 page “White Paper” entitled Scholarship Reconsidered: A Promotion Think Tank White Paper across campus (Báez et al., 2023). The white paper defined multiple scholarship types, shared pros/cons for reconsidering scholarship, and delivered both short-term and longer-term strategies for implementing changes to the full professor promotion process.

The white paper aimed to define and articulate holistic forms of scholarship to better align our mission and evaluation structures with the “very serious work that many faculty on campus do for their positions, but do not get evaluated or compensated for” (Báez et al., 2023). Because most promotion criteria at this university emphasize traditional research activities and the scholarship of discovery (i.e., “basic” research), the white paper articulated and emphasized how the institution must come to recognize and regard other forms of scholarship, including the scholarship of integration, application, teaching and learning, and creative works. Ultimately, the white paper outlined several immediate recommendations that have potential to positively impact the future of how we define and reward inclusive and engaged scholarship at the university. Some of the specific action items included:

-

Collecting information on what tasks/responsibilities faculty are currently doing that are not easily categorized within current promotion criteria.

-

Being a change agent by facilitating conversations to move units forward to revise promotion to full professor criteria.

The white paper also offered this definition of scholarship adopted from Seattle University:

“Scholarship is defined broadly to include basic research, the integration of knowledge, the transformation of knowledge through the intellectual work involved in teaching and facilitating learning, and the application of knowledge to solve a compelling problem in the community. The department values an inclusive view of scholarship in the recognition that knowledge is acquired and advanced through discovery, integration, application, teaching, and engagement.”

Finally, the white paper encouraged these reconsiderations of scholarship as a way forward “to maintain the university as a healthy and vibrant academic institution” (Báez et al., 2023).

The goal was to share this community-based reflection to spark inspiration and discussion both amongst the participants themselves and in the broader community. The final white paper was released to as many campus constituents as possible, based on a list generated by the community partners to ensure a wide distribution across audiences from individual units, to college and university leadership, and shared governance members.

Phase 2: Considered Conversations

One short-term strategy generated by the think tank was to continue the discussions spurred in the original think tank and to share and get feedback on the white paper concepts from the larger campus community. To that end, individual think tank members signed up to share the white paper to targeted people, via email to the campus listserv, and ensured that it was included in shared governance communications. However, a more strategic dissemination approach was implemented the following term. First, we invited two different virtual presentations by national experts, and both received a copy of our white paper in advance. Both presentations were advertised widely to the campus. The first presenter focused on how the scholarship of engagement changes to promotion processes unfolded at their (research intensive) university, and the other discussed the benefits of an inclusive definition of scholarship of engagement to serve equity and diversity goals. Both presenters also explicitly discussed the white paper.

Second, several of the original think tank members led what we called “Considered Conversations” where they convened small groups of their colleagues to read and discuss the white paper as it related to their unit. This included a considered conversation with the Provost and her leadership team of Deans and Associate Provosts. This also included a considered conversation with shared governance members (one member of our think tank was the past-president of the campus faculty assembly) as well as a drop-in conversation open to any who might have missed out. The informal gatherings took place both on- and off-campus, typically over lunch, and were structured on the “Considered Conversations Guide” (see Appendix B) developed by our team. These meetings led to rich discussion, as well as significant and thoughtful debate. Pushback was not the norm, but was certainly encountered, and our guide anticipated some of the concerns and offered strategies for handling (e.g., concerns that CES is less rigorous, see Appendix B). These meetings ensured continued community partnership and also set the foundation to challenge assumptions and strategize bold efforts to improve the full professor review process and criteria for evaluating community-engaged scholarship. At the conclusion of each considered conversation, participants were given a charge to take the white paper back to their departments for additional conversations. They were also encouraged to take a lead role in catalyzing their departments to revise their promotion criteria based on the white paper recommendations.

Phase 3: Member Checking

We created two surveys 1) to measure think tank members’ experience and 2) to document faculty perceptions of the resulting new CES evaluation processes. While we did not have any pre-post measures, our goal was less about measuring change and more about measuring satisfaction.

First, immediately following completion of the white paper, we sent an anonymous evaluation survey to think tank members to assess their perceptions of the process of partnering on reimagining the promotion pathway to include the scholarship of engagement and the outcomes from the think tank. This evaluation included items about the value of the individual sessions, their perceptions of positive benefits that will result from the white paper, and their sense of accomplishment and ability to contribute to the white paper. The evaluation survey was returned by all think tank members, with the exception of those of us on the organizing team. Results of this survey indicate the participants highly valued the three think tank sessions with 70% agreeing or strongly agreeing Session 1 was a valuable use of time and 100% of participants agreeing or strongly agreeing Session 2 and 3 were a valuable use of time. One participant noted “I thought it was well-organized, respectful of diversity of expertise, and a good use of time. It made me feel hopeful about the future of [University Name] and higher ed in a way that I generally am not.” Other feedback from participants included, “Good mix of faculty from different levels and in different colleges,” “helped bring light to unspoken elements of the RPT process,” and “Conversations uncovered barriers that some might not notice that limits others.”

Regarding their expectations about the potential impact of the white paper, 79% of participants believed the White Paper they created would have a beneficial impact on the pathway to full professor on campus with one participant noting, “I think the white paper can be beneficial for motivating conversations about the process and how to “reconsider scholarship.” However, I do think that it is important to continue to find ways to sustain and fan motivation and interest in the topic. Keep the paper in front of folks.” Further, all participants agreed or strongly agreed they felt free to discuss their ideas about reimagining the pathway to full professor and all agreed or strongly agreed to feeling a sense of accomplishment in contributing to the creation of the white paper. One participant added, “I’ve never been shy in expressing my thoughts and opinions, anyway, but the way the think tank was run and the fabulous folks involved created a wonderful opportunity to freely share.” Overall, the sentiment from the think tank members was positive regarding the structure and activities, lending to participants feelings of accomplishment and optimism about the impacts of the white paper.

Second, to assess faculty perceptions of scholarship following the think tank and Considered Conversations, we conducted a campus-wide climate survey of tenured and tenure-track faculty. The survey aimed to document how well multiple ways of knowing, including Community-Engaged Scholarship (CES), are currently recognized and rewarded at the university. A total of 147 faculty members responded. Of these, 54.4% identified as women, 40.1% as men, 1.4% as gender-nonconforming or another identity, and 4.1% did not disclose their gender identity. The sample was predominantly white (61.2%), with 9.5% identifying with historically marginalized racial or ethnic groups (e.g., Black, Hispanic, Pacific Islander), 8.2% identifying as Asian, and 21.1% opting not to report race or ethnicity. The respondents represented a balanced range of faculty ranks: 34% were assistant professors, 30.6% associate professors, and 31.3% full professors. The remainder either held distinguished titles or chose not to disclose their rank. On average, respondents had been at the university for 12.3 years (median = 8 years, range = 1–45 years).

While the climate survey was part of a broader evaluation effort, it included targeted items to assess the influence of our team’s initiatives to elevate CES within faculty evaluation processes. Notably, faculty who felt greater institutional support for engaged scholarship also reported higher job satisfaction (r = .22, p < .001) and stronger intentions to remain at the university (r = .18, p < .001); these reflect important indicators of a positive organizational climate.

The activities of our catalyst team and those set forth in the white paper (i.e., developing resources, workshops, and community-building efforts for faculty pursuing promotion to full professor) also showed measurable impact. Faculty who perceived greater support from these efforts reported a greater sense of belonging (r = .28, p < .001), higher job satisfaction (r = .20, p < .001), and greater stated likelihood of staying at the university over the next five years (r = .20, p < .001).

Importantly, faculty with historically minoritized identities (M = 4.36, SD = 1.55) reported feeling more supported in their engaged scholarship than their white colleagues (M = 3.68, SD = 1.70; t(107) = -1.89, p = .03). This finding is particularly significant, as research consistently shows that minoritized faculty are more likely to engage in CES-related work (Settles et al., 2021). These results suggest that our intentional focus on campus-wide conversations and structural support for CES is resonating with those who have historically been underrecognized for this type of scholarship.

Though these results are descriptive, they serve as a meaningful form of member checking, validating the relevance and impact of our efforts. Taken together, the survey findings reinforce the value of the think tank and associated programming in shifting campus culture toward broader recognition of engaged scholarship and strengthening support systems for faculty committed to CES.

Phase 4: Action Items

Following the considered conversations, the final phase of our project was to partner with change agents at the campus level and adapt exemplars from other institutions who had successfully addressed the issue of promotion in CES (including Purdue University, Seattle University, and Iowa State). It was important that the action items were not just cut and paste from the work done in other places, and instead reflected the needs and issues raised by our campus community. As part of our PRM process, it was important to adopt materials to our university’s context and allow for the generation of new resources and structures. Ultimately, we focused on and implemented five action items as noted in Figure 2: a) the addition of “holistic” promotion criteria to include community and institution building in (as of this writing n = 11) different departments; b) a standing committee to encourage the revision of full promotion evaluation criteria to be more inclusive of multiple forms of scholarship; c) a revised faculty success web-based tool to assist faculty with tracking their impacts; d) a dossier repository and sample CES vita template; and e) reviewer resources, templates, and instructions for how to review CES. The resources are listed in Table 2 and most are publicly available. Unless otherwise noted, the resources were also made available on the Provost’s website to ensure easy access for candidates, department chairs, and reviewers. We were careful to review the templates with Deans and HR liaisons of each college to member-check before posting the final templates.

We focused on these items as a first step in positively impacting how the university defined and rewarded inclusive and engaged scholarship. While these five strategies were initially geared toward reforming the promotion to full professor evaluation, they can also inform earlier stages of career progression.

Action Item #1: Revise Departmental Promotion Criteria

Several white paper authors and several department leaders (who were not part of the think tank) felt empowered by recommendations in the white paper to become change agents and lead their departments to revise their promotion to full professor criteria (n = 11 departments as of this writing). They added criteria that highlights community-engaged scholarship, public impact, and other identified forms of scholarship, including the scholarship of teaching and learning and integrated scholarship. For example, one unit’s criteria now reads:

“The department seeks to expand, qualify, and clarify what is meant by the terms “substantial, significant, and continued growth, development, and accomplishment” to be in conversation with, considerate of, and in response to what the department considers inclusive scholarship (including the scholarship of discovery, integration, application, engagement, teaching and learning, and creative works). This broadly conceived conceptualization of faculty work takes into account the various impacts of faculty work inside and outside of the university (e.g., within communities where many of us work) to better align with our institutional vision. Moreover, given the breadth and depth of the discipline of geography, it is critical that our criteria encapsulate the broad scope of geographic teaching, scholarship, and leadership and service.”

And another unit’s criteria now reads:

“The department recognizes that scholarship can take many forms. Our department emphasizes fundamental discovery, scholarly work that integrates existing knowledge, and applied research. We recognize scholarly study of teaching and learning issues in our field as a form of research.”

Action Item #2: Forming a Faculty Assembly Criteria-Review Advisory Committee

To further develop the infrastructure needed to sustain units in revising their promotion to full evaluation criteria, the white paper recommended the creation of a newly formed Faculty Assembly committee (see Appendix C for committee bylaws). Working together with the shared governance leaders, the white paper authors and the catalyst team, they finalized a charge for the committee:

1. Establish bylaws, to be voted on by the Faculty Assembly, including how members will be recruited to ensure diverse representation.

2. Establish procedures for reviewing the promotion process for units and providing recommendations back to the unit.

3. Establish processes for soliciting feedback and recommendations for constant improvement.

4. Provide a general timeline for collecting promotion documents and providing comments and recommendations back to an academic unit.

5. Provide a recommended timeline for administrative review/approval, including review/approval by the Dean and the Provost, and posting to the Provost’s website.

6. Develop mechanisms for publishing data about the outcomes of promotion decisions and demographic data of faculty ranks and make this information more accessible to the campus community.

7. The Committee will work with the Faculty Records Coordinator to receive criteria documents for any unit that is seeking feedback on their promotion process.

Ultimately, this review committee would commit to raising awareness about the types of scholarship to consider in annual merit and/or promotion criteria and offer guidance sessions and feedback to departments updating their criteria (the committee is currently awaiting a final vote of approval from Faculty Assembly). Academic units seeking input and review of their annual merit and/or promotion criteria could reach out to this committee for recommendations as well, and those recommendations would be based on a rubric designed to ensure transparency, clarity, equity, and holistic evaluation in relation to the annual review and tenure and promotion processes (see Appendix D for the evaluation criteria scoring rubric, which was adapted from O’Meara et al., 2021).

Action Item #3: Assisting faculty with tracking their impacts using a revised web-based tool

To support the tracking of CES impacts, the team led the revision of the dossier management system used for annual merit evaluations and promotion processes to incorporate new ways for faculty to track the impacts of their scholarship. This web-based tool formerly included a section titled “Service”. Working together with the Office of Research and the Provost’s Office, we updated this category to “Service and Leadership”, better capturing more of the work faculty do to run the university, including institution-building activities. In the area of “Scholarship and Research,” we added a new section for “Public Scholarship Engagement” which lists activities directly related to community-based participatory research, including: information sharing, consulting/advisory efforts, policy work, presentations, collaboration, problem solving, co-creating definitions and outputs, assessment/evaluation, demonstrations, and media projects, as well as a fill-in-the-blank other category for endeavors not captured by these activities.

Action Item #4: Sharing a dossier repository and sample community-engaged scholarship vita template

One way to expose the hidden, unwritten rules of promotion is to create examples that model successful presentation of faculty evaluation criteria (Matthew, 2016; Niemann et al., 2020). As such, one recommendation in the white paper was to create a repository with (voluntarily shared) examples of promotion dossiers, including examples of dossiers that feature CES. The dossiers are maintained by the Office of Research and are only shared by invitation and only after acknowledging confidentiality requirements. While these dossiers are not available publicly, we would encourage other campuses to create an internal sharing system.

In addition to the dossiers, we also made available a sample curriculum vitae template (see Appendix E) that offers categories for faculty to draw upon when conveying their community-engaged scholarship. This template is posted on the Office of the Provost website so that it is accessible to candidates.

Action Item #5: Reviewer Resources and Invitation Template

Once a CES scholar provides their CV and dossier to their department committee, the process leaves the candidate’s hands and enters the review process. As such, we designed template invitation letters and instructions for reviewers to refer to when writing their recommendation for CES promotion candidates (Appendix F). Language in the templates clearly outlines the purpose of external reviews in the request letter, including providing explicit information about holistic evaluation criteria, institutional policies, and names the different type of scholarship. Reviewers are also provided a link to a copy of The Guide: Documenting, Evaluating, and Recognizing Engaged Scholarship (Able & Williams, 2019) to inform their recommendation writing.

In Closing

Traditional metrics of success used in the faculty promotion evaluation process undervalue the vital work of CES and community-based participatory research practices. Our PRM approach and results highlight one possible way to effectively and equitably evaluate CES without forcing epistemological assimilation of “common” traditional measures of impact (e.g., citation counts). Too often community-engaged scholars are asked to “fit in” with traditional discovery performance standards to gain legitimacy. Our goal was to use participatory research methods to create both rapid short-term solutions (e.g., templates for CVs, resources for reviewers, rubrics for evaluating criteria, and sample dossiers) and long-term strategies (e.g., revised promotion criteria, new shared governance structures) to support community-engaged scholars in their career progression. Our results demonstrate meaningful change at one university and, we hope, inspire solutions to support the career progression of community-engaged scholars elsewhere. In doing so, we contribute to the literature on participatory research methods by demonstrating how PRM can be applied not only to knowledge production and community engagement, but also to institutional change. Our work expands the scope of PRM by showing its utility in reshaping academic structures and policies through collaborative, faculty-driven processes.

Acknowledgements

The project reported here was funded by the National Science Foundation under award Grant No. 2117351. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. For the first author (Smith), this material is based upon work supported by (while serving at) the National Science Foundation. We are grateful to the Seattle University ADVANCE team and the West Virginia University ADVANCE team for their collaboration and coaching. We owe a very special thank you to Dr. Jodi O’Brien at Seattle University and Dr. Steve Abel, Purdue University for their input, expertise, and mentoring throughout the process.