Introduction

Contemporary global crises are calling for a global cultural shift around how to think of them and tackle solutions (Fletcher et al., 2024). In this context, Living Labs (LLs) were seen as a promising approach for shaping responses to Sustainable Development Goals (i.e., SDG; Molnar et al., 2023; Rodrigues & Franco, 2018), such as improving health and well-being, countering climate change, and reducing socioeconomic inequalities (Malekpour et al., 2023).

LLs were defined as both a research methodology (Dell’Era & Landoni, 2014) and means driving societal change (Zavratnik et al., 2019). For example, framing LLs within a co-creation paradigm, Zavratnik et al. (2019) defined them as systems supporting the uptake of elements promoting sustainable living, such as “circular economy, digital transformation, and local self-sufficiency” (p. 1). Furthermore, LL were conceived as being embedded in a multitude of contexts, with an emphasis on the stakeholders’ daily life features (Konsti-Laasko et al., 2012; Stahlbröst & Bergvall-Kareborn, 2008). As such, LLs may be acknowledged as open dynamic systems, which functioning both aim to foster innovation in and are shaped by context (e.g., Bergvall-Kareborn et al., 2009; Feurstein et al., 2008; Leminen et al., 2012).

Over the past years, LLs addressed a variety of issues, ranging from health and technology to sustainable urban and rural development (Dekker et al., 2020). Crucially, their generative experimentation promised to reframe the way in which we think and aim for sustainability (Kimbell & Bailey, 2017; Molnar et al., 2023). Aiming to improve citizens’ daily lives in a sustainable fashion (Nyström et al., 2014), many LLs focused on health promotion (e.g., Habiyaremye, 2020; Korman et al., 2016) and prevention (e.g., Asthana & Prime, 2023; Dietrich et al., 2021). For instance, where a LL in Switzerland focused on nutrition to address older adults’ frailty (i.e., Senior Living Lab; Angelini et al., 2016), the MACVIA-LR Living Lab (i.e., Contre les MAladies Chroniques pour un Vieillissement Actif en Languedoc Roussillon) aimed to reduce their loss of autonomy and number of hospitalizations owing to falls and chronic diseases (e.g., Bousquet et al., 2016). The implementation of health-related LLs has also led to a focus on patients’ use of health technologies (e.g., Boulay et al., 2011), on the sustainable building of urban spaces promoting physical activity (e.g., Wäsche et al., 2021), and on the improvement of socio-health systems based on patients’ experiences (e.g., Aguirre et al., 2016). Furthermore, increasing attention was directed to migrants’ social integration (Karimi et al., 2022), and to the promotion of their health (Rustage et al., 2021). However, the wide range of areas addressed by LLs challenged the clear definition of their underlying processes, criteria, and objectives.

The promises of these participatory and collaborative ventures led to a proliferation of LLs in Europe (McPhee et al., 2017), as well as to a growing scientific body of work (Ballon & Schuurman, 2015; Leminen et al., 2017; Schuurman & Leminen, 2021). Mirroring the lack of a consensual definition (Lucchesi & Rutkowski, 2021), the practices and processes applied in LLs varied greatly across the explored topics, and the involved stakeholders and organizations. Previous research highlighted the ongoing implementation of different approaches of coordination and participation (Leminen, 2013; Tercanli & Jongbloed, 2022), as well as innovation processes and tools (Leminen & Westerlund, 2017). Where this diversity of practices enabled societal problems to be approached from different angles (Markard et al., 2012), it entailed challenges in clearly establishing the boundaries of LL’s field of action. Thus, scholars settled upon criteria characterizing LLs, in an attempt to standardize the practices and differentiate them from other participatory and collaborative approaches (e.g., Almirall & Wareham, 2011; Hossain et al., 2019; Steen & van Bueren, 2017). For example, Hossain et al. (2019) advocated that LLs should be rooted in real-life contexts, include stakeholders from different backgrounds, organize activities based on models and networks, use methods tailored to objectives, address societal challenges, whilst ultimately focusing on citizens’ needs through a sustainable approach. Along tensions and inconsistencies surrounding what is considered a LL, major concerns emerged regarding the evaluation of its effectiveness (Burbridge, 2017; Ivanova & Huizenga, 2023; Paskaleva & Cooper, 2021).

The crucial social role endorsed by LLs called for evidence on their effectiveness at different social levels (e.g., Paskaleva & Cooper, 2021). Providing evidence on the effectiveness of LLs though became hampered by the sheer variety of methods used (e.g., Zimmermann et al., 2023), potentially compromising standardization as a gatekeeper of quality and recognition (Holmes et al., 2010; Ochsner, 2024). The paradigm shift introduced by LLs in the approach toward sustainability (Kimbell & Bailey, 2017) was accompanied, however, by an alignment of practices and methods to the challenges they tackled (e.g., LaMarre & Chaberlain, 2022). Thus, numerous scholars sought to account for the effectiveness of LLs notwithstanding the multitude of methods harnessed therein, notably through a focus on features supporting and manifesting the usefulness of LLs.

The success and effectiveness of LLs, as understood in terms of attaining the pre-established goals, was the focus of a wealth of academic reflection (e.g., McPhee & Schwarz, 2023; Yilmaz & Ertekin, 2024). Numerous scholars outlined factors (e.g., Berberi et al., 2023; Juujärvi & Pesso, 2013; Yilmaz & Ertekin, 2024) and guidelines (e.g., Compagnucci et al., 2021; Dekker et al., 2020) designed to foster the effective implementation of the LL design in a wide range of contexts and topics. For example, in a scoping review, Berberi et al. (2023) identified barriers and facilitators to the success of a LL, including, on the one hand, cost, temporal, and technical limitations (e.g., participants technological skills) and, on the other hand, opportunities brought by close collaborations and iterative processes. Furthermore, in a practice-oriented comparative study of LLs across different countries, Valkokari et al. (2023) stressed the need for a shared vision and common values, and for a structure orchestrating the collaborations. When it came to assessing these factors and processes, however, there was a lack of consensus and standardization, which ultimately tended to jeopardize the effective implementation and the outcomes of LL practices (Yilmaz & Ertekin, 2024).

Evaluation is also a grey area and a source of tension in the LL literature (Greve et al., 2020; Voytenko et al., 2016). Some hard-hitting critics warned against the lack of evidence on the effectiveness of LLs, thus raising concerns about their usefulness (e.g., Cyr et al., 2022; Paskaleva & Cooper, 2021). This issue might stem both from the nascent stage of this research field (Schuurman et al., 2015), implying the lack of a unified framework for evaluation (Kovács, 2016), and from the complexity of the processes that were intended to be evaluated (Paskaleva & Cooper, 2021). Hence, over the past few years, many scholars sought to outline possible indicators for evaluating LLs that were aligned with their area of research. For example, Beaudoin et al. (2022) proposed indicators for evaluating the processes involved in LLs, including their costs and benefits, their social impacts (i.e., stakeholders’ values and willingness), and their environmental impacts – such as the sustainable nature of the produced outcomes. This approach encompassed a major public and scientific importance, by legitimizing the political, financial, and organizational support given to LLs, and in progressively improving practices through the evaluation-produced knowledge (van Waes et al., 2021). However, to the best of our knowledge, no study attempted to compile a comprehensive inventory of indicators aimed at facilitating the evaluation of the effectiveness of LLs.

Interest of this literature review

The present scoping review sought to provide an overview of the approaches currently employed to evaluate LLs and their outcomes. More specifically, building on the grounds set by previous work in this research field (e.g., Hossain et al., 2019) and aligning with the understanding of LLs as open dynamic systems (Leminen et al., 2012), we focused on the nature of the impact yielded by LLs, its scope, the factors that might influence outcomes and processes, and the methods used for evaluation. In addressing this issue, we ultimately aimed to chart evaluation tools potentially adoptable by practitioners, parent organizations, and researchers alike, as part of their hands-on experience in LLs. This purpose was aligned with central directions in the LL research agenda, encouraging the evaluation of both processes and the extent to which these set-ups are effective (Beaudoin et al., 2022). Thus, our work was structured upon the following research question: What are the indicators for assessing the effectiveness of participatory and collaborative processes used in Living Labs?

Methods

The present scoping review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018) and the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines (Peters et al., 2020). A protocol of this scoping review was registered in the International Platform of Registered Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (INPLASY) on May 15, 2024 (registration number 202450072; Martinelli et al., 2024).

Eligibility criteria

The present scoping review considered as potentially eligible different types of literature sources, including published and unpublished (i.e., gray literature) primary sources of evidence, and literature reviews (e.g., systematic reviews), as their methodology was not considered an eligibility criterion. Literature sources were deemed eligible if written in English or French. While population characteristics were not considered for study inclusion or exclusion, literature records had to involve a human population. Consistent with the concept around which this literature review was structured, studies were eligible if they took place in the context of a participatory and collaborative LL-type approach or self-identified it as LL. Literature sources were included if they mentioned indicators, measures, or metrics for evaluating the impact of LLs, and/or entailed a qualitative self-assessment of their effectiveness in terms of process or outcomes. Study attributes, such as the geographical location or the year of publication, were not considered as inclusion criteria. Study quality was not considered an exclusion criterion for the selected studies (see Peters et al., 2020).

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted between July 15, 2022 and November 01, 2022, and was updated between May 15 and 21, 2024. Electronic databases for the search of peer-reviewed articles were Business Source Premier & CINAHL, Cairn, Google Scholar, Proquest, Swisscovery, and Web Of Science. Grey literature resources were systematically searched in the following electronic databases: ArODES, Lvivo, DART Europe, and LiSSa. Furthermore, the reference list of included studies was searched for inclusion of additional items. In accordance with McGowan et al. (2016), the systematic search was synergistically performed by two authors, which were supported by a researcher-librarian.

To identify relevant search terms for the aims of this review, a preliminary search was undertaken on Google Scholar and on the MeSH thesaurus. Hence, for both peer-reviewed and grey literature we systematically searched the above-mentioned databases for the terms “living lab”, “indicator”, “evaluation”, “assessment”, “metric”, and “measure”. For grey literature only, the search terms “health” and “sustain” were used to further narrow the inquiry. To capture all permutations, we used a wildcat operator (i.e., “*”), and search terms were combined through Boolean operators. An example of a search for peer-reviewed literature in Web of Science was: “living lab” OR “living labs” AND “indicator*” OR “evaluat*” OR “assessment” OR “metric*” OR “measur*”. This was processed by Web of Science as: (TI=(“living lab” OR “living labs”)) AND ALL =(indicator* OR evaluat* OR assessment OR metric* OR measur*). Where possible, filters were applied to select text language (e.g., in Swisscovery, the filter excluded articles written in Korean, Japanese, Russian, or Portuguese). For full search equations refer to Table A (Supplementary materials).

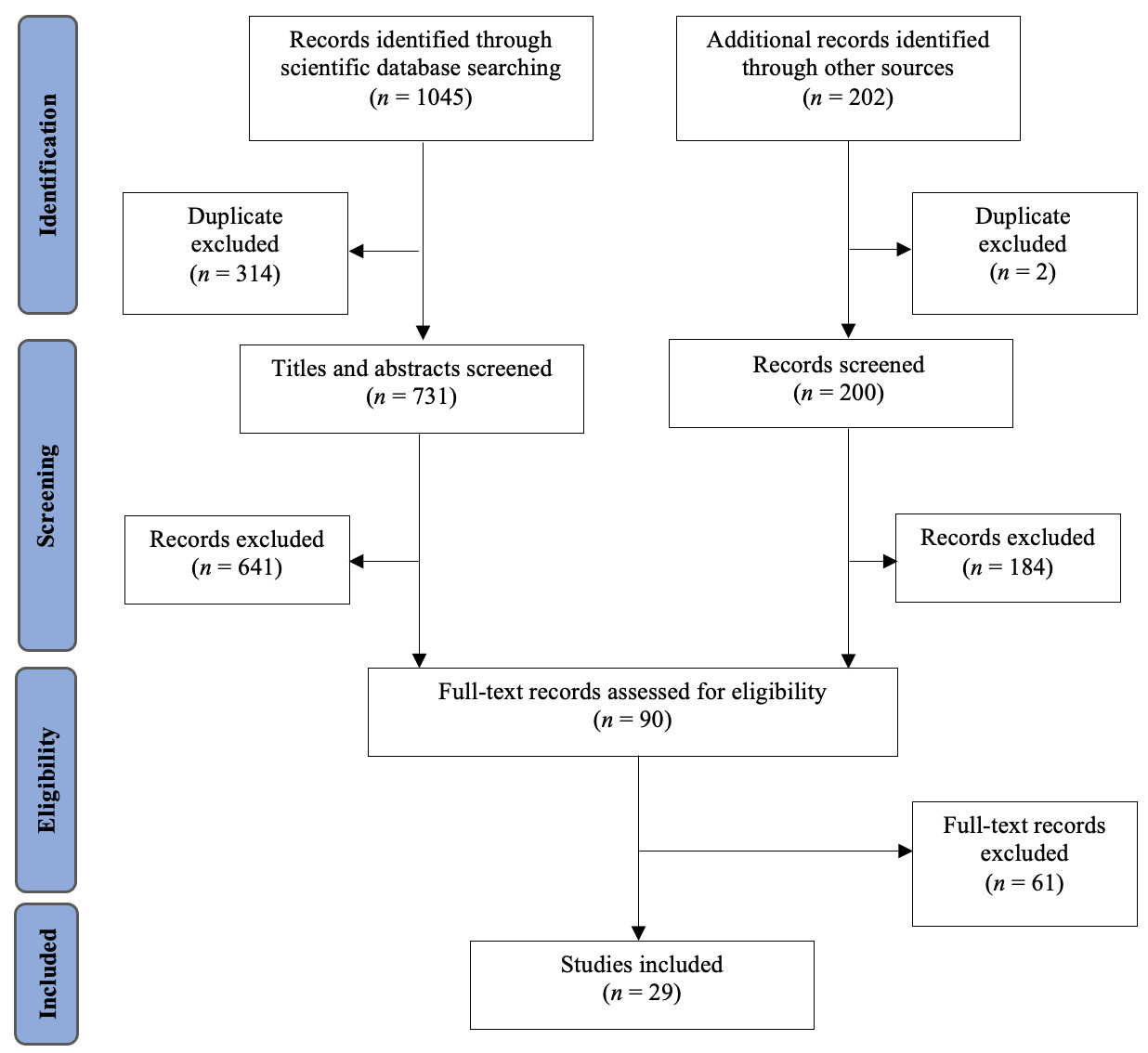

Evidence screening and selection

Following the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines (Peters et al., 2020), two independent authors screened the selected studies (N = 1247) in two stages, after removal of duplicates (n = 316). For instance, the screening process was initially completed by a PhD student and a university professor, and finally updated by an additional PhD student. First, titles and abstracts were screened (n = 931). Second, the full text was screened (n = 90). During both screening stages, articles that did not meet the eligibility criteria were deleted (see Figure 1). Disagreements between authors were solved through discussion. The percentages of agreement between reviewers were calculated and exceeded the 85% agreement threshold for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., 2018). For peer-reviewed studies the authors reached 90.68% of agreement, and 89.81% for all literature sources.

Data extraction

First, we extracted study information from relevant literature sources, including authors’ names, year of publication, geographical location, and type of publication. Then, building on the research question, a data charting was performed to identify the relevant impact types of LLs. Thus, information relating to the following areas was extracted: type of impact, scope of impact, contextual factors influencing impact, and method of evaluation. Disagreements between authors were solved through discussion.

Data synthesis

Extracted data were analyzed both qualitatively and quantitatively. Consistent with our objectives, priority was given to a qualitative analysis of the extracted data. Accordingly, the areas of impact assessment (i.e., types of impact, scope of impact, contextual factors influencing impact) were described and specific categories and sub-categories were identified. This enabled a mapping of the effectiveness indicators, which was supported by examples. Descriptive quantitative analyses were also undertaken. We calculated the frequency of studies encompassing the effectiveness evaluation of LLs among the screened literature records, as well as the areas of effectiveness assessment identified in the included studies. Furthermore, we drew up a spider plot illustrating the distribution of the various impact assessment indicators.

Results

Of the studies emerged in the literature search, only 29 addressed the issue of evaluating the effectiveness of LLs (2.33%). The included studies described impact assessment in different terms, focusing 1) on the nature of the impact generated by the LL, 2) its scope, and/or 3) both internal and external contextual factors potentially influencing outcomes (Table 1). Where the impact was primarily assessed using qualitative methods (n = 18, 62.07%), through semi-structured interviews, ethnographic observations, or workshops, quantitative methods were also employed (n = 13, 44.83%) by administering questionnaires to participants – such as local community members, patients, families, health professionals, informal caregivers, or city representatives. Some studies used both qualitative and quantitative methods (n = 8, 27.59%), and others did not specify the type of method used to evaluate the impact of the LL (n = 6, 20.69%).

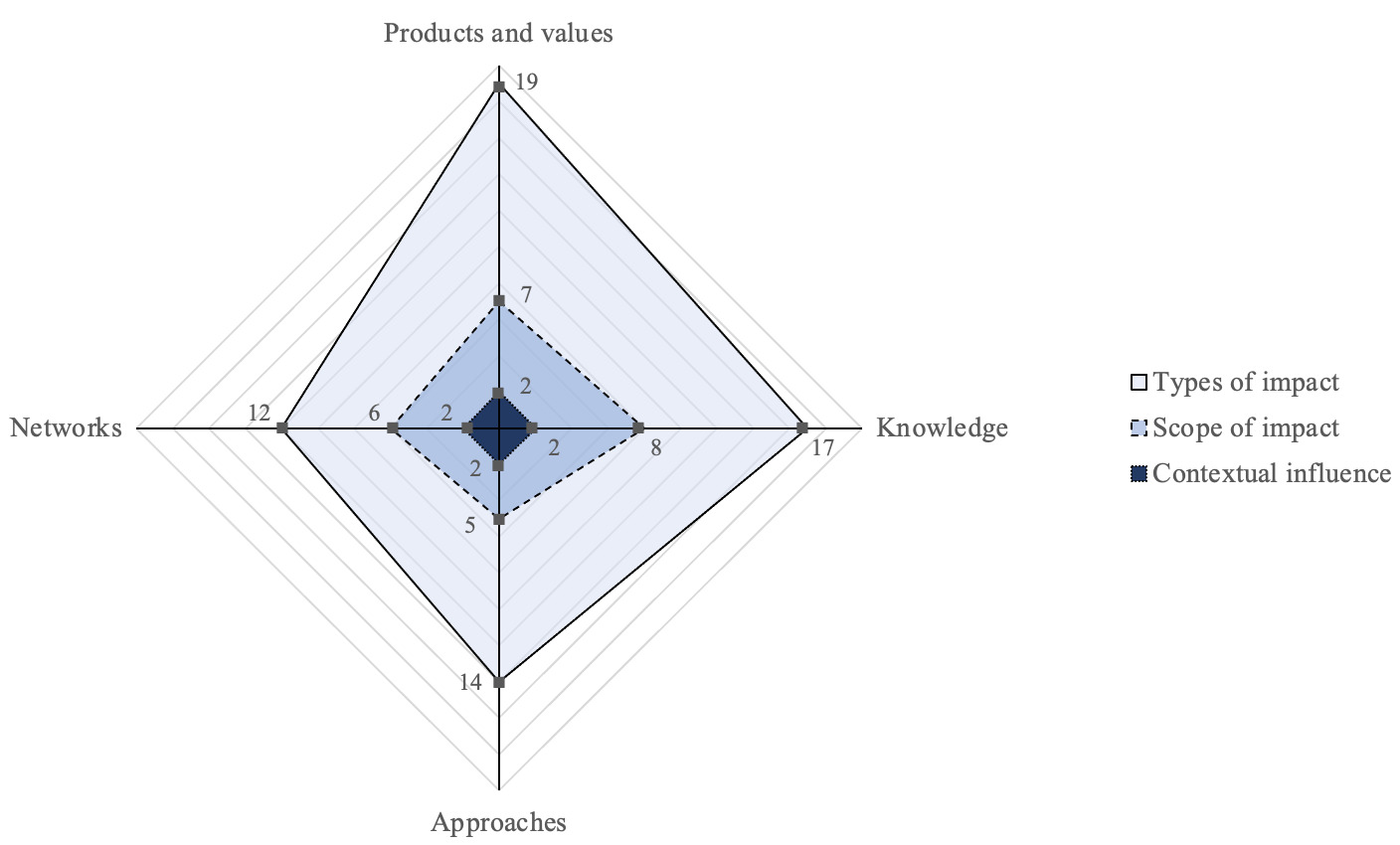

Figure 2 illustrates the degree to which the three dimensions of evaluation were integrated into the assessment of LLs, and highlights a primary focus on the nature of the impact rather than its scope or influencing factors. The following paragraphs outline the categories of impact type, scope of impact, and contextual influences, supporting them with examples drawn from the included studies.

Types of impact

LL impacts were deemed tangible (n = 24, 82.76%) or intangible (n = 17, 58.62%). Indicators of tangible impacts referred to LLs outcomes that could be directly observed, measured, and quantified. Tangible impacts included, for instance, concrete innovation and development of products and values (n = 19, 65.52%, Figure 2), as well as improved knowledge, skills, and behaviors (n = 17, 58.62%, Figure 2). The indicators of intangible impacts referred to a change of perceptions, relationships, and social dynamics, being less directly measurable. Intangible impacts included a change in approaches and views (n = 14, 48.28%, Figure 2), and a development of networks and relationships between people (n = 12, 41.38%, Figure 2). Each category of tangible and intangible impact was operationalized with different indicators (Table 2).

Studies measuring tangible impacts in terms of products and values, assessed both innovations and programs resulting from LLs. The effectiveness of LLs was considered as resulting from the co-construction of a social and open innovation, reflecting the objectives and life contexts of the LL’s stakeholders (e.g., Eschenbächer et al., 2010; Kletz & Marcellin, 2019; Paskaleva & Cooper, 2021). This innovation was related to the development of products, data, ways of working or services. More specifically, the creation of products implied a tangible impact arising from the objectives, needs, and obstacles of the stakeholders’ real-life contexts. For example, Dekker et al. (2020) described the iterative process of progressively improving products, such as technologies, in a Dutch LL bringing together city representatives, NGOs, researchers, local citizens, and asylum seekers. Other studies considered the impact in terms of usefulness of the innovations produced, focusing on their mobilization and experimentation by future users (e.g., Fuglsang et al., 2021; Mastelic, 2019; Tanda & De Marco, 2021). For instance, by gathering people highly committed to sustainable everyday practices in a LL (i.e., researchers, local government members, and local community members strongly committed to climate change issues), an association was founded to enable other community members to experiment with low-carbon living (Sharp & Salter, 2017). Impacts in terms of innovation or added value was also understood through the development of policy interventions, fostering a better understanding of complex problems and their possible resolutions (e.g., Bouwma et al., 2022; Dekker et al., 2021). Notably, Bouwama et al. (2022) described the contribution of three Dutch LLs in improving the understanding of common goals for sustainable agriculture in the Netherlands, and in translating these into locality-specific goals. Moreover, the organization of events resulting from LLs was regarded as a tangible impact. For example, Osorio et al. (2018) measured the number of training sessions, contests, and workshops that the LL enabled to set up between employees and users.

Tangible impacts were also evaluated with regard to the emergence of knowledge and skills, as well as behavioral change, at both individual and collective levels. Studies evaluated citizens’ gain in skills and knowledge (e.g., Beaudoin et al., 2022; Pino et al., 2014; Sharp & Salter, 2017), such as a better understanding of cancer risks and prevention, as well as a reduction in fatalism (Russell et al., 2021). Furthermore, the impact of LLs was assessed in terms of citizen engagement into community issues, and changing norms (e.g., Caspers et al., 2023; Mastelic, 2019; van Geenhuizen, 2018), such as agricultural behavioral norms (Beaudoin et al., 2022). For example, a LL in Turin promoted the use of cleaner transport, and preservation of nature and environment (Tanda & De Marco, 2021). In the context of health, these impacts were similarly described as improvements in health literacy, medication intake, and health systems (e.g., Kletz & Marcellin, 2019; Pino et al., 2014; van Geenhuizen, 2018). Specifically, LLs of co-creation between patients, informal caregivers, and health professionals enabled the use of experiential knowledge to develop innovative healthcare services (Kletz & Marcellin, 2019) and to empower patients in disease management (Pino et al., 2014). Moreover, the knowledge generated was assessed on the basis of understandability and transparency of policies and (shared) decision-making (e.g., Konsti-Laakso et al., 2018; Tanda & De Marco, 2021; van Geenhuizen, 2018).

The intangible impacts assessed in the reviewed studies included a change in approaches and visions fostered by the LL initiative. Improved collaboration between stakeholders and their greater inclusion in public services was considered as an intangible contribution (e.g., Fuglsang et al., 2021; Konsti-Laakso et al., 2018; Russell et al., 2021). More particularly, LLs were thought to act as niche spaces that foster democratic engagement (Fuglsang et al., 2021) and citizens’ satisfaction (Haugh & Mergel, 2021). The inclusion of public employees in this collaborative space likewise fostered the development of public approaches being more responsive to citizens’ needs, such as health promotion and prevention of social or healthcare services (Fuglsang et al., 2021; Kletz & Marcellin, 2019; Russell et al., 2021). Impacts were also envisioned as a change in future users’ views (Osorio et al., 2018; Paskaleva & Cooper, 2021), including the improvement of population’s knowledge on supports offered in dementia care resulting from the LUSAGE Living Lab – a LL bringing together patients, healthy older adults, families, and formal and informal caregivers to adapt technologies aimed at supporting older adults with dementia (Pino et al., 2014). Other research claimed that LLs function as a glue gathering otherwise dispersed and inaccessible information and people (Eschenbächer et al., 2010; Fuglsang et al., 2021). Similarly, the impact was considered in terms of the sharing of visions between stakeholders (Mastelic, 2019), which enabled, for example, an improvement of university students’ collaborative skills, such as teamwork and partnership building (van Engelenhoven et al., 2023).

Intangible impacts were also addressed through the creation of networks, relationships, and community dynamics. Some LLs evaluated their effectiveness through the implementation of a meeting place (Eschenbächer et al., 2010; Osorio et al., 2018), seen as a space potentially energizing citizens’ curiosity and sense of belonging (Osorio et al., 2018). Furthermore, LLs were considered to have had an impact through their lasting transformation of social dynamics (e.g., Dekker et al., 2021; Kletz & Marcellin, 2019; Swist et al., 2022), such as the addition of social value to participate in activities proposed after the LL (Haugh & Mergel, 2021). The change in social dynamics was also described as an increase in mutual aid, solidarity, and social action (Dekker et al., 2021; Kletz & Marcellin, 2019; Zamani et al., 2023). Moreover, the authors assessed the effectiveness of the LL by its ability to anchor itself in the territory, and to include marginalized users in a social and economic perspective of healthcare systems (Haugh & Mergel, 2021). This mobilization of users was further evaluated in terms of community development, featuring, for instance, older adults concerned with living place issues (Konsti-Laakso et al., 2018).

Scope of impact

The assessment of effectiveness advanced by the included studies concerned the measurement of the scope of impact, expressing the extent and significance of the changes brought by a LL (n = 11, 37.93%). As shown in Figure 2, the scope of impact was evaluated on a social (n = 7, 24.14%), temporal (n = 1, 3.45%), and spatial scale (n = 1, 3.45%), or by estimating gains in value and recognition (n = 5, 17.24%). Table 3 illustrates the indicators used to measure the different types of scope of impact.

In measuring the social extent of the LLs outcomes’ impact, studies focused on the number of people involved in the process (Beaudoin et al., 2022; Kletz & Marcellin, 2019; Russell et al., 2021), and on the diversity characterizing the collaborative groups (Bronson et al., 2021; Dekker et al., 2021; Osorio et al., 2018). For example, while Pino et al. (2014) reported on the number of users and industrial partners directly involved in the LUSAGE Living Lab activities, Dekker et al. (2021) described the different participating groups, such as asylum seekers, young people, and neighborhoods. Although less evaluated than other dimensions, the temporal scope was described in a systematic literature review in terms of LLs outcome evaluation phases, which can be preliminary, planned, in progress, or completed (Bronson et al., 2021). Being similarly underestimated, the evaluation of spatial impact was performed when the LL enabled the implementation of new products, from an innovative perspective. Notably, Kayaçetin et al. (2022) evaluated circular and bio-based constructions resulting from a LL in Ghent, and qualitatively investigated their impact on workers, local communities, society, and consumers. Assessment of the value and recognition provided by LLs was based on various indicators, including the number of projects resulting from the LL (Bouwma et al., 2022; Osorio et al., 2018; Pino et al., 2014), funding received (Sharp & Salter, 2017), media coverage (Osorio et al., 2018; Pino et al., 2014; Swist et al., 2022), and scientific outreach (Osorio et al., 2018; Pino et al., 2014).

Contextual influences

As LLs needs to be considered as open dynamic systems, the assessment of their impact was often associated to an acknowledgement of the factors possibly shaping the environment and their outcomes. The influencing factors considered in the reviewed studies were both internal (n = 3, 10.35%), accounting for the functioning of the process, and external (n = 4, 13.79%) to the LL, relating to the context within which the LL was embedded. Both internal and external influences encompassed specific factors, presented in Table 4.

Internal factors related to the organization of the LL, influencing the co-creation process (Haugh & Mergel, 2021; Zipfel et al., 2022). For example, Haug and Mergel (2021) emphasized the importance of a physical space characterized by a stimulating atmosphere, to promote the co-creation process between employees, external users, public servants, and digital volunteers. Participants’ individual motivation was also considered as influencing the outcomes of the LL internally, being discussed alongside the temporality of activities implementation (Haugh & Mergel, 2021; Zipfel et al., 2022). For instance, Ziepfel et al. (2022) suggested that user motivation might be reduced by an overly rapid or sluggish implementation of LL activities. Furthermore, authors suggested that the LL’s objectives needed to be adapted to the city’s targets, ensuring impact when achieving them, such as the focus on technologies, services, and the environment of a LL in Turin that brought together city representants, researchers, and locals (Tanda & De Marco, 2021). Some studies also highlighted the importance of internal collaborative dynamics in fostering the LL impact. For example, techniques promoting participation, as well as openness to change and communication, were employed at every stage of a LL to guarantee its successful implementation (Zipfel et al., 2022).

Among the external factors influencing the process and outcome of a LL, authors identified the role of support from the organizations coordinating the activities (Haugh & Mergel, 2021; Tanda & De Marco, 2021). For instance, Tanda and De Marco (2021) spotlighted the significance of the role of the initiating organization, such as a city council, in ensuring citizen involvement in LL activities. Furthermore, the LL’s autonomy and governance structure played a crucial role in its impact. Notably, the LL’s autonomy worked through the independence of its members from higher-level decision-makers in shaping the activities it undertook (Haugh & Mergel, 2021). Along with its autonomy, the LL’s organizational structure was thought to influence its outcomes (Haugh & Mergel, 2021; Zamani et al., 2023)). Drawing on an example of a responsive city in Tehran, Zamani et al. (2023) emphasized the importance of the system’s self-organization, which is enhanced by freedom from the city’s hierarchical structures and enables greater citizen participation. The successful implementation of the LL was also strongly associated with its resources. Being allocated by the parent organization, Haug and Mergel (2021) considered personal, technical, and financial resources to be external. Moreover, macro-social phenomena may influence and compromise the achievement of the LL’s objectives and progress. For example, Van Engelenhoven et al. (2023) described the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a LL focused on university students’ collaborative skills, such as through the digitalization of exchanges and collaborations between participants.

Co-occurrence of effectiveness indicators – Evaluation of impact scope and contextual influencing factors according to impact types

A spider plot was constructed to illustrate the distribution and co-occurrences of the evaluation of impact types, impact scopes, and contextual influencing factors (Figure 3). Like Figure 2, Figure 3 showed a predominance of evaluating tangible impact types, and revealed less attention paid to the scope of impact and contextual influencing factors than to the assessment of impact type, as highlighted by the small overlap of the shaded areas. Figure 3 also illustrates the co-occurrences between evaluation domains, unveiling the evaluation arenas, expressed in terms of the types of impact brought by LLs, wherein impact scope and contextual influences were assessed. More specifically, there was a trend towards measuring the extent of impact when the impact was tangible. For instance, authors more frequently described and measured the extent of impact when LLs provided new products and values (n = 7) or new knowledge (n = 8). Conversely, studies less frequently assessed the extent of intangible impact, such as on approaches and visions (n = 6) or on networks (n = 6). Figure 3 also suggested that studies proportionally measured the extent of impact more when it was an intangible impact compared to a tangible impact. For instance, 50.00% of network impact studies measured the extent of impact, while only 36.84% of LLs that produced new products and values took the scope of impact into account. Finally, although consideration of contextual influences is the least represented dimension, it appears to be evenly distributed between the different types of impact.

Discussion

To our knowledge this scoping review was the first to map the approaches and indicators that scholars used to evaluate the effectiveness of LLs. Results showed the use of a wide range of methods, approaches, and indicators for the evaluation of LLs effectiveness. In assessing LLs, researchers primarily focused on the impact produced by the resulting projects, with particular attention directed toward tangible impacts. Although less widespread, previous research also attempted to assess the extent of this impact, notably in terms of the people for whom the LL or its outcomes were beneficial, and the gain in value and social recognition. Few studies examined contextual influences, thus portraying LL evaluation practices as more descriptive than predictive. These insights might be further understood through the prism of evaluation as a means of nourishing the LL process and legitimizing its practice. Mirroring the lack of consensual definitions, the variety of effectiveness indicators further highlighted the necessity of an onto-epistemological reflection on the assumption that underpin them.

Comparison with previous work

By identifying different indicators of tangible and intangible impact, our findings extend early outcome-type conceptualizations of LLs (Hossain et al., 2019; Veeckman & Temmerman, 2021). Diverging from previous research (Hossain et al., 2019), we considered the gain in knowledge and the change of norms (i.e., concept, ideas) as a tangible contribution of LLs. These effects or changes might indeed be operationalized and measured using methods and tools from the social and political sciences and psychology (e.g., Costenbader et al., 2019; Israel et al., 2005), therefore aligning with the tangible impact definition. Furthermore, indicators that were considered as neither tangible nor intangible, such as social, service, and systemic innovation (Hossain et al., 2019), were deemed to be intangible in the present work, to avoid confusion in their further implementation by researchers and non-academics. Moreover, the different types of impact indicators identified resonated with the topics around which LLs were articulated hitherto (e.g., Borda et al., 2024). More specifically, the predominant use of tangible impact indicators might derive from LLs’ early focus on technologies, sustainable energy, territorial development, and private sector, being areas aimed at concrete innovations that mainly adopt a pragmatic approach (Dekker et al., 2020).

Along with earlier work, this literature review pointed to a research trend toward evaluating the tangible impact of LLs, prompting scholars and citizens to focus on the concrete and measurable issues and outcomes. By reviewing previous studies, however, we highlighted the growing use of intangible impact indicators to appreciate the value of the participatory process underlying LLs. Moreover, by showing a primary focus on outcomes, through impact indicators, rather than on methodological aspects, this literature review suggested a tendency of studies to adopt participatory evaluation in assessing LLs (e.g., Brandon & Fukunaga, 2014; Rosenthal et al., 2015).

Evaluation as nourishing and legitimizing process for LLs

The types of impact indicators identified in this literature review illustrated the meso-level role of evaluation for LL projects (Schuurman & Leminen, 2021). Calling on participatory evaluation principles, indicators relating to knowledge and behavior and to approaches and views might not solely be aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of the set-up, but also at nourishing participants’ involvement (Odera, 2021). For instance, by engaging participants in the assessment, they might in turn gain knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Henry & Mark, 2003; Patton, 2008), making evaluation an embedded and transformational feature of the LL (King et al., 2007; Mertens, 2009). In this meso-level perspective of evaluation, impact indicators act as a support for thinking and action within the LL, enabling unexpected intangible changes to be captured and described (Cabaj, 2014). This echoes the major directions intended for the LL movement, notably including iterative learning for future projects based upon past activities (Leminen & Westerlund, 2019). Yet, the degree to which the various impact indicators were employed in the reviewed studies might also reveal the role of evaluation for LL organizations, at a macro (or mega)-level (Schuurman & Leminen, 2021; Thees et al., 2020; Vervoort et al., 2022).

The evaluation of the impacts produced by a LL is fundamentally part of a response to criticism of effectiveness evidence, by demonstrating their added value (Ballon & Schuurman, 2015; Paskaleva & Cooper, 2021). Thus, the description of tangible rather than intangible impacts, such as product innovation and development, might suggest a tendency toward legitimizing tangible effects as ‘real evidence’. This is consistent with the need for participatory designs to prove their usefulness as socially and politically valued approaches (e.g., Nguyen et al., 2022; Nguyen & Marques, 2022; Voorwinden et al., 2023) – stemming from a positivist paradigmatic outlook on what is legitimately knowledgeable, demonstrable, or effective (e.g., Adams et al., 2005). In this perspective, LL organizations might privilege the evaluation of tangible impacts in a quest for political legitimacy (e.g., Lewis, 2015; Williams & Lewis, 2021), being considered as the veritable potential of these set-ups (Hagy et al., 2017). More particularly, concrete evidence would provide justification for continued funding beyond a pilot project (Dayson, 2017). The tendency to gear evaluation towards legitimizing and endorsing the approach was also illustrated when we looked at the scopes of impact measured in the reviewed studies.

The trend in past research towards evaluating the extent of the impact mainly in social and value terms, might reflect the consideration of evaluation as an approach that fosters the long-term viability of the LL (Cabaj, 2014; Gamble et al., 2021). By proving the social scope, such as the number of people reached, and the value of the LL, such as in terms of received funding, scholars legitimize the set-up before social and political institutions, ensuring its perpetuation (e.g., Dayson, 2017; Nguyen et al., 2022). Yet, the scant consideration of temporal and spatial scope, as well as contextual influences on LL dynamics, appears to be at odds with flagship principles of this approach. When considering longevity and territorial anchoring as key characteristics of LLs (e.g., Hossain et al., 2019), researchers ought to be more concerned with the temporal and spatial consequences of the implemented projects. Similarly, as the dynamics of interaction and co-creation are at the very heart of the LL concept (Almirall & Wareham, 2011; Hossain et al., 2019; Steen & van Bueren, 2017), greater attention needs to be turned to elements that may influence them at both the meso- and macro-level of the LL (Schuurman & Leminen, 2021). The lesser emphasis on measuring impact scope and contextual influences, as compared with impact types, illustrated a tendency towards disregarding standardized measures shared across a research field, echoing the approach of developmental evaluation (Cabaj, 2014; Lam & Shulha, 2015; Patton, 2011). Thus, methods and indicators might appear to be selected to suit the issues tackled by the LL and the dynamics characterizing it.

The reviewed studies did not use effectiveness indicators for the sole purpose of evaluating their approach, as these measures served a meso- and macro-social role in ensuring the continued functioning of LLs. Assessing participants’ increased knowledge, behaviors, and approaches may have strengthened their integration and endorsement of the LL participatory approach. Moreover, the predominant use of tangible indicators suggests a temptation among researchers to align with socially and institutionally valued forms of impact – thereby demonstrating the worth of LLs and securing continued funding. Despite the need for institutional recognition through impact assessment, scholars have to refocus the evaluation of LLs effectiveness on the core tenets of this approach, such as its longevity and participatory nature. For instance, the methodological patterns revealed by previous studies call upon an onto-epistemological debate tailored to LLs.

Reflecting on the onto-epistemological roots of LLs and their evaluation

The variety and co-occurrence of indicators and methods employed in the evaluation of LLs, as illustrated by the spider plot, underlines the need for complementary approaches and tools to fully grasp the dynamics at work in this system. Beyond the standardization criticisms that could be addressed, this heterogeneity of methods is the results and promote understanding of open and complex systems (e.g., Bosisio, 2020; Bosisio et al., 2013; Bosisio & Santiago-Delefosse, 2014), such as those at work within LLs. More specifically, the use of a wide range of methods, tools, and indicators offers a way of adapting evaluation to the numerous and different challenges broached through LLs (e.g., Baum, 1995; Bosisio & Santiago-Delefosse, 2014; Smajgl & Ward, 2015). Viewing LLs as adaptive intermediaries between science and society (Abi Saad & Agogué, 2024), the response addressed to societal issues might therefore be jointly and reciprocally interpreted through the mobilization of a plurality of effectiveness indicators (Bosisio, 2020; Bosisio & Santiago-Delefosse, 2014). Moreover, this plurality of evaluation practices might facilitate communication in a highly interdisciplinary set-up (Bosisio, 2020; Bosisio & Santiago-Delefosse, 2014). With regard to this literature, in order to strengthen the validity of LLs, improve the evaluation of their impacts and, therefore, foster their political and institutional scope, it is essential to engage in an onto-epistemological reflection on LLs.

Indeed, the multitude of methods employed in the reviewed studies suggests that LLs are consistent with socio-constructivist approaches (e.g., Santiago-Delefosse & del Rio Carral, 2017). In this regard, though, LLs usually aim at an adaptation of methods to the context and the actors in play (Abi Saad & Agogué, 2024). Yet, a pragmatic approach cannot be considered a valid epistemological standpoint in research (Bosisio, 2020). In addition, the need to assess the impacts of LLs through quantifiable indicators promote institutional and political recognition in a positivist vein (e.g., Adams et al., 2005). Mixed methods research might provide a framework for such reflection, since several scholars argued that quantitative methods, jointly collected, analyzed and interpreted with qualitative data, are consistent with the ontology and epistemology promoted within the socio-constructivist approach (e.g., Bosisio, 2020; O’Hanlon, 2018; Shannon-Baker, 2016). A much-needed reflection though is necessary in order to develop methodologies that assess LLs in a way that is consistent with the principles of mixed methods research in a socio-constructivist paradigm.

Additionally, since LLs are collective productions that are best understood when the interactions between actors and their context are taken into account (Santiago-Delefosse & del Rio Carral, 2017), lived experience might be central in the assessment of the effectiveness and impacts of a participatory process (e.g., Jagosh et al., 2012; Santiago-Delefosse et al., 2015; Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020). Indeed, an assessment made unilaterally by political decision-makers and scientists fundamentally challenges the role of participants as experts (e.g., Duea et al., 2022). These questionings align with epistemological debates on governance dynamics in participatory projects (e.g., Foster & Glass, 2016; Herberg & Vilsmaier, 2020; Lake & Wendland, 2018), seeing users often disempowered in the LL decision-making (Leminen, 2013).

The co-construction of methods and the conception of a shared expertise between stakeholders might also benefit the recognition of LLs evaluation quality, essential in spite of the standardization required to assess their effectiveness and impacts. Where evaluation guidelines might facilitate the overcoming of standardization constraints (Springett et al., 2011), the collective framing of LLs evaluation – that is involving participants in the design of the assessment endeavor – might be crucial to the quality of the approach. For instance, in health sciences qualitative research, quality is guaranteed by appropriate, stated, transparent and detailed methods (Santiago-Delefosse et al., 2016). Therefore, scholars have to clearly establish the role of users in the evaluation process and to promote their integration when adapting methods to the context under study. Participatory research methods, moreover, generate both quality through collective reflection and their ability to demonstrate the practicability of the results produced (Streck, 2016), and internal validity by ensuring the comprehensibility of the approaches, the acceptance of the results, and their holistic nature (Bleikenbergh et al., 2010). Thus, considering users’ lived experience in the co-construction of LL evaluation approaches would serve to ensure recognition of their quality. From this perspective, the evaluation of LLs needs to adopt a systemic approach, whereby LL productions can only be appreciated through a synergetic consideration of the stakeholders (Cargo & Mercer, 2008; Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020).

Like the LL itself, the evaluation of its effectiveness needs to be adaptive and combine interdisciplinary methods to increase the validity of the assessment. Such efforts have to be part of broader onto-epistemological reflections placing the plurality of methods, and LL’s contextual and co-constructive nature within a socio-constructivist approach. This would foster a greater consideration of participants’ lived experiences when assessing the impact of LLs. The lack of standardized assessment practices highlighted in previous studies, also suggests that engaging in such a debate would prompt further consideration on how to ensure the quality of the evaluation.

Limitations

Notwithstanding the contributions of this scoping review to the field of LL evaluation, some shortcomings need to be acknowledged when considering the identified indicators of effectiveness. First, to date, literature reviews may not be able to capture all the work undertaken in the field of LL, based solely on peer-reviewed or grey literature. With more than 480 active LLs around the world (ENoLL, 2024) and a focus other than on scientific publication (Laborgne et al., 2021), the evaluation of LL might have been conveyed through other channels, such as websites and blogs, which were not considered in our work. This might have led to not considering indicators of effectiveness, and we suggest that future research include more variable sources of information. Second, in trying to map and categorize effectiveness indicators we may have confounded evaluation approaches related to different topics. This might have threatened the aim of our work to create a concrete evaluation tool transferable across disciplines. Thus, future research is encouraged to understand and identify which indicators are most relevant to different issues and disciplines. Third, the quality of the included studies was not assessed – such a procedure being not required for scoping literature reviews (Peters et al., 2020). This might have reduced the quality of the information reported in this scoping review, considering that scientists’ work in this emerging field was occasionally reported in low-quality or predatory journals. However, the narrative and descriptive approach adopted in this literature review could have limited the scope of this issue.

Conclusion

This scoping review fitted into the supporting role attributed to research in the running of LLs, shedding light on the tension-filled area of evaluation. The evaluation approaches included indicators of impact, measures of scope, and consideration of contextual influencing factors. Notably, scholars primarily focused on the definition and implementation of impact indicators, providing evidence of the usefulness and effectiveness of LL organizations and projects. These approaches illustrated a role for evaluation within LLs, aimed at fueling its functioning, as well as legitimizing its social and political value as a platform for responding to contemporary global issues.

These findings raise implications for both LL organizations and researchers active in the field. The concrete usefulness of evaluation as a means of nourishing user participation within the LL, encourages organizations to implement evaluation as part of the co-creation process, rather than seeing it solely as an avenue for legitimizing practices. Scholars are urged to pursue research into the evaluation of LLs, in particular by seeking to distinguish thematically specific indicators and formulating methods for their measurement and assessment. With this outlook, a longitudinal evaluation of projects, rather than a mere description of their outcomes, would enable LLs to be highlighted as a means of bringing about concrete change, while involving users over a longer timeframe. The LL field of research should also engage in an interdisciplinary dialogue on the epistemological foundations of its practices, which we endeavored to introduce to some extent. The role of evaluation in recognizing the legitimacy of LLs might be strengthened by an epistemological grounding, establishing a common thought framework for practices despite the variability of the contexts and issues addressed.

This scoping review has brought to light the transversal role of evaluation in LLs. We trust that these efforts will encourage LL organizations to consider researchers and evaluation as an opportunity for the development of LL practices.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere gratitude is extended to the librarian-researchers of the School of Engineering and Management Vaud (HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Western Switzerland, Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland), who facilitated the preparation of the literature searches on which this work was structured.

Author contributions

PM was responsible for drafting and pre-registering the scoping review protocol, updating the literature search, writing the original manuscript, reviewing, and editing it. NC was responsible for the initial literature search, identification of categories and sub-categories of effectiveness indicators, and revision of the manuscript. FB supervised the work, and was responsible for the initial literature search, identification of categories and sub-categories of effectiveness indicators, and revision of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly funded by HES-SO.

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Corresponding author

Corresponding author: Paolo Martinelli, School of Engineering and Management Vaud, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland. Email: paolo.martinelli@heig-vd.ch