Social media is not only a site of communication but also a contested space where knowledge is produced, controlled, and withheld. It serves as a powerful instrument for activism, community advocacy, and education, particularly for young adults who have historically been excluded from institutional decision-making and knowledge production (Michalak et al., 2023). However, these platforms are not neutral spaces; they are governed by corporate interests (Hearn, 2008) and algorithmic logics that determine whose knowledge circulates and whose is suppressed. Indeed, social media has the potential to serve as an emancipatory tool for knowledge mobilization, yet it also operates within surveillance capitalism, where the very data young people generate is extracted, commodified, and used to shape their digital realities in ways that are often invisible to them (Pangrazio & Selwyn, 2018).

Knowledge mobilization, which is the process of translating research into accessible and actionable insights, has historically relied on conventional academic dissemination methods such as peer-reviewed journals, conferences, and institutional reports. These formats are largely inaccessible to the general public and particularly to young adults from equity-deserving groups, who face systemic barriers to participation in research discourse (Michalak et al., 2023). The exclusion of these groups from knowledge production and dissemination is not incidental but structural, reinforcing epistemic hierarchies that privilege academic expertise while devaluing experiential knowledge (Rao, Jardine, et al., 2024).

Despite these exclusions, young adults are not passive recipients of knowledge; they actively seek, critique, and produce it, especially in digital environments. Social media, in particular, has become a tool for participatory knowledge production, where young people collectively construct meaning, challenge dominant narratives, and engage in alternative knowledge-sharing practices (MacKinnon et al., 2021). Unlike traditional research dissemination, which often assumes a unidirectional flow of knowledge from experts to the public, social media facilitates dynamic, iterative exchanges that allow young adults to shape how information is interpreted and mobilized. However, the extent to which these participatory practices translate into research engagement remains underexplored. Research institutions are increasingly using social media for public outreach, but these efforts often replicate extractive knowledge practices, using digital platforms as one-way channels for information dissemination rather than spaces for genuine co-creation and engagement.

The challenges of digital knowledge mobilization are further compounded by structural inequities in access to information. Social media platforms are designed to prioritize engagement-driven content, which does not always align with the principles of research integrity or accessibility. Algorithmic bias influences what knowledge is surfaced and what remains hidden, creating disparities in whose voices are amplified. Minoritized communities, including young adults with mental health-related disabilities (Rao, Dimitropoulos, Milaney, et al., 2024), often turn to social media to find solidarity and challenge dominant narratives, yet their visibility (Rao, Dimitropoulos, Milaney, et al., 2024) remains precarious, subject to platform policies that regulate discourse in ways that are often opaque and inconsistent.

These complexities necessitate an examination of how participatory research can leverage social media not only as a tool for dissemination but as a space for genuine co-creation of knowledge. This requires moving beyond instrumentalist approaches that treat social media as merely a means to broadcast research findings and instead recognizing it as a contested space where power is negotiated, and where knowledge mobilization must be designed with a critical understanding of its constraints and possibilities. As such, the aim of this study is to examine the intersection of participatory research, knowledge mobilization, and social media, with a particular focus on engaging, including and imagining with young adults from equity-deserving and hardly reached communities. It interrogates how different forms of social media content, ranging from advocacy-driven posts to educational materials, shape engagement, whose voices are included or excluded in digital knowledge mobilization efforts, and how young adults navigate the complexities of social media as both a tool for agency and a mechanism of control. This manuscript reflects both how we implemented participatory methods and why our findings speak to the knowledge mobilization of participatory work. In doing so, it aims to inform and support other young adults seeking to lead their own participatory research, demonstrating the impact of youth-led inquiry.

Methodology: Young-Adult-Led Participatory Research in VOICE

The Valuing Opinions and Inspiring Change through Engagement (VOICE) Study emerged from the Helping Enable Access and Remove Barriers To Support for Young Adults with Mental Health-Related Disabilities (HEARTS) Study, a patient-oriented research initiative that engaged young adults as Patient RESearch partners (PARES). The HEARTS study has been documented in detail elsewhere (Rao, Dimitropoulos, Jardine, et al., 2024; Rao et al., 2025; Rao, Jardine, et al., 2024), but it remains a critical foundation for understanding how participatory research can evolve. HEARTS advanced engaged scholarship by prioritizing young adults with lived and living experience as meaningful partners in the research process, integrating their expertise into every aspect of the research study. However, despite its participatory approach and intentions, HEARTS was still led by an institutional researcher and situated in the academy, reflecting the persistent structural reality that young adults are often included in research without being positioned as leaders of it.

Despite this limitation, the HEARTS study challenged the traditional concept of capacity-building, which implies a top-down approach where institutional researchers “upskill” lived experience partners. Instead, it embraced a capacity-sharing model that recognized multiple ways of knowing and valued the expertise that all team members, institutional researchers and young adults alike brought to the process. This model, reinforced through ongoing dialogue about power dynamics, psychological safety, trust-building, and trauma-informed and culturally responsive practices, created an environment where young adults could develop the skills, confidence, and experience necessary to take on leadership roles in future participatory research.

The VOICE study represents a direct outcome of this process. The lead researcher for VOICE (AP) had never conducted research before participating in HEARTS, yet through engagement in the HEARTS study, developed the expertise necessary to independently lead VOICE as a fully young-adult-led participatory research initiative. In a significant, poignant and important role reversal, the doctoral candidate who led HEARTS is now in a supporting role, providing guidance and stepping back to support young adults to shape and direct their study. This reversal is not only symbolic but also methodologically significant, illustrating how participatory research can move beyond traditional academic hierarchies to create authentic leadership opportunities for young adults. This shift in leadership structure represents an evolution in participatory methodology, demonstrating that capacity-sharing in one study can lead to sustained research leadership in another.

The HEARTS study provided several key insights that shaped the methodological design of VOICE. First, while patient-oriented research aims to center lived experience, traditional strategies and approaches remain inaccessible to many young adults, limiting the impact of research beyond academic audiences (Rao, Dimitropoulos, Jardine, et al., 2024). Social media presents an opportunity to bridge this gap, as young people are already online and actively engaging with digital content. Second, HEARTS demonstrated that participatory engagement must be flexible and adaptive to accommodate the varied responsibilities, health needs, and capacities of young adults over time (Rao, Dimitropoulos, Jardine, et al., 2024). Furthermore, the study underscored the role of trust-building in research participation, particularly for young adults who have had previous negative experiences with tokenistic or extractive research (Rao, Dimitropoulos, Jardine, et al., 2024). Finally, HEARTS revealed both the opportunities and challenges of using social media for knowledge mobilization—in a publication that is currently under review, highlighting the need to address algorithmic bias, digital inequities, and ethical concerns in online research. Building on these findings, the VOICE study was developed as a participatory and emancipatory initiative led by young adults and created for young adults, applying and extending the lessons of HEARTS while centering young adult leadership at every stage of the research process. Unlike HEARTS, where young adults were highly engaged but ultimately did not have the full opportunity to lead due to institutional expectations, VOICE represents a shift in power dynamics, with young adults leading the research while institutional researchers take on a mentorship and facilitation role rather than a directive one.

Developing Participatory Methods

In trying to figure out our bespoke methods, we drew from emancipatory and activist research. Emancipatory research seeks to dismantle traditional power imbalances within the research process, ensuring that those most affected by a given issue have control over how it is studied, analyzed, and disseminated (Hoffman-Cooper, 2021). In the context of VOICE, this meant positioning young adults with lived experience as the architects of the study, rather than merely contributors. The transition from HEARTS to VOICE was facilitated by the recognition that meaningful participatory research requires more than engagement; we felt it required a structural shift that allows coresearchers to become research leaders. This redistribution of power exemplifies the iterative and transformative potential of emancipatory research methodologies (Hoffman-Cooper, 2021).

A key tenet of emancipatory research is reflexivity—researchers must critically examine their own positionality, biases, and influence on the research process (Tuck & Yang, 2014). In VOICE, this was achieved through a structure in which decision-making authority rested with the young adult co-researchers, ensuring that the one institutional researcher operated in a supporting role rather than an authoritative one. This aligns with the call for researchers to consider how their work contributes to social justice, ensuring that research is not only about/describes minoritized communities but is conducted in ways that actively challenge systemic inequalities (Hoffman-Cooper, 2021).

Activist research is characterized by its commitment to social change, moving beyond knowledge production to actively challenge oppressive structures and advance transformative outcomes (Jones, 2017). Traditional research, even when critical of inequities, often stops short of taking action. Activist research, by contrast, is rooted in the belief that scholarship should be a tool for advancing equity and dismantling systemic barriers (Jones, 2017). The VOICE Study embodies this principle by leveraging social media not only as a site of knowledge dissemination but as a mechanism for mobilizing young adults in digital advocacy. Jones (2017) outlines three core characteristics of activist research that are evident in VOICE: (1) the combination of knowledge production and transformative action, (2) systematic multi-level collaboration, and (3) challenges to power. Rather than approaching social media merely as a tool for distributing research findings, VOICE engaged young adults in examining and critiquing the structures that shape digital knowledge mobilization.

The study actively interrogated the barriers created by corporate social media platforms, including algorithmic suppression of advocacy-oriented content and digital inequities that limit access for minoritized young people. By doing so, VOICE is not just describing or documenting these challenges; it is providing a platform for young adults to collectively strategize around more equitable approaches to knowledge mobilization, embodying the principles of activist research (Jones, 2017). The study also exemplified systematic multi-level collaboration. Unlike traditional participatory research, in which institutional researchers often maintain control over research objectives and dissemination strategies, VOICE was co-created at every stage. The young adult co-researchers determined study priorities, shaped dissemination strategies, and engaged in iterative cycles of content creation, testing, and adaptation. This process mirrored the collaborative, power-sharing approach advocated in activist research, in which those affected by systemic barriers play a direct role in shaping the interventions designed to address them (Jones, 2017).

Finally, VOICE actively challenged power structures, both within the research process and in the broader digital landscape. The study examines how corporate control over social media platforms limits the visibility of young adult research-driven advocacy, highlighting the ways in which algorithmic decision-making reinforces existing social inequalities. It also critiques the exclusion of young people who opt out of digital spaces, underscoring the need for alternative, youth-driven knowledge mobilization strategies. By bringing these challenges to the forefront, VOICE positioned itself not only as a research study but as a form of digital activism, reinforcing the central premise of activist research: that research should not merely describe oppression but actively work to dismantle it (Jones, 2017).

By drawing on both emancipatory and activist research traditions, the VOICE Study extends the boundaries of participatory research. While HEARTS made significant strides in engaging young adults as co-researchers, it remained institutionally led. VOICE builds on HEARTS by demonstrating that participatory research can—and should—go further. It is not enough for research to engage young adults; it must create pathways for them to lead. Moreover, it must not only document barriers to equity but actively seek to dismantle them. The transition from HEARTS to VOICE illustrates how participatory research can evolve over time to further shift power. In HEARTS, young adults were partners in research. In VOICE, they are the drivers of it. This transition represents an ongoing process of redistributing power. This aligns with the core principles of both emancipatory and activist research, reinforcing the idea that participation should not be an endpoint but rather a stepping stone toward greater autonomy and leadership. As participatory research continues to evolve, studies like VOICE provide a roadmap for how research can be designed not only with but by young people.

Critical Reflexivity: Positionality Statement From the Young Adults Researchers

With the exception of one minoritized doctoral student researcher providing support, this study was envisioned, designed, and led entirely by young adults. We are a team of young adult researchers with diverse and intersecting identities. Many of us identify as racialized and cisgender women, some of us are first- or second-generation immigrants and all of us live and study in Western or Eastern Canada on colonized Indigenous land. These positionalities are not incidental; they shape how we understand and approach the complexities of social media as a tool for connection, equity, and justice. All co-authors of this paper, including the young adult research leaders, contributed to the positionality statement and to the design that shaped this project. We chose to co-author this paper collaboratively to reflect the shared leadership and reciprocal nature of our work. We acknowledge that others, such as the VOICE Champions who generously offered feedback and opinions on our social media posts, were vital to the project but are not listed as co-authors. This is because their involvement, while valued and recognized, did not extend to research design, analysis, or writing. These contributions are instead acknowledged in the paper as part of our broader community of engagement.

We understand that equitable research is not a static accomplishment but a continuous process; equity is a practice, and we would like to genuinely reflect on our practices and limitations of this study. As researchers, we recognize the inherent tensions in attempting to engage in non-extractive, participatory research, even outside formal institutional settings. We are positioned within systems that reward academic outputs, and while this project was not institutionally affiliated, we still benefit from the social capital and career advancement that publishing affords. Even though everyone contributed to the project, not everyone benefits from it in the same way, especially in terms of academic or professional rewards—especially since all contributions to this project were voluntary and without financial compensation. We acknowledge that the ability to engage in unpaid research reflects a level of privilege and not everyone can afford to work without monetary support, and this reality inevitably shapes who is able to participate fully.

In reflecting on our collaborative process, we also considered the dilemma of deference, which is a concept explored in the book Elite Capture (Táíwò, 2022). Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò cautions against institutional tendencies to elevate marginalized voices in symbolic ways, while failing to engage with them critically and equitably. It is important to see these voices as intellectual collaborators rather than symbolic representatives. We do not see participation as a simple act of “deferring to” lived experience, but as a commitment to ongoing dialogue. This requires trust and reflexivity during the research process and in how we present and publish our work.

For many of us, social media has been a central part of our lives from a young age, particularly during pivotal moments such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This lived and living experience gives us a unique perspective on how social media can simultaneously be a site of liberation and oppression. While it has amplified minoritized voices, fostered activism, and provided platforms for storytelling, it has also exposed our communities to hate, misinformation, and harmful stereotypes. Our research is also informed by an awareness of the structural barriers that shape access to and use of social media. In Canada, colonial legacies continue to silence Indigenous voices and limit access to resources for equity-deserving groups. While public spaces such as libraries are often cited as solutions to digital inequities specifically, these assumptions fail to account for systemic issues like transportation challenges, safety concerns, and the broader context of digital literacy. These barriers are especially pronounced for equity-deserving and hardly reached communities. As such, the VOICE study rejects simplistic dichotomous narratives about social media as either entirely beneficial or harmful. Instead, we recognize it as a complex and contested space that reflects the systemic inequities embedded in our society. Its global reach makes it a powerful tool for amplifying minoritized voices, but it also creates opportunities for misinformation and erasure. Meaningful messages often get lost amidst viral trends, and the very algorithms that prioritize engagement can perpetuate bias and inequity.

The VOICE study is set apart by its leadership of young people who bring both lived and research-based insights into the role of social media. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on detached observation, our work is grounded in the realities of how social media intersects with our identities, relationships, and communities. The VOICE study reflects a commitment to using social media intentionally and ethically as a tool for equity and inclusion. We strive to amplify minoritized voices and ways of knowing, challenge harmful narratives, and foster community through digital platforms.

Study Design

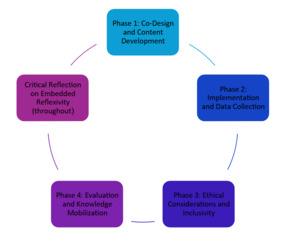

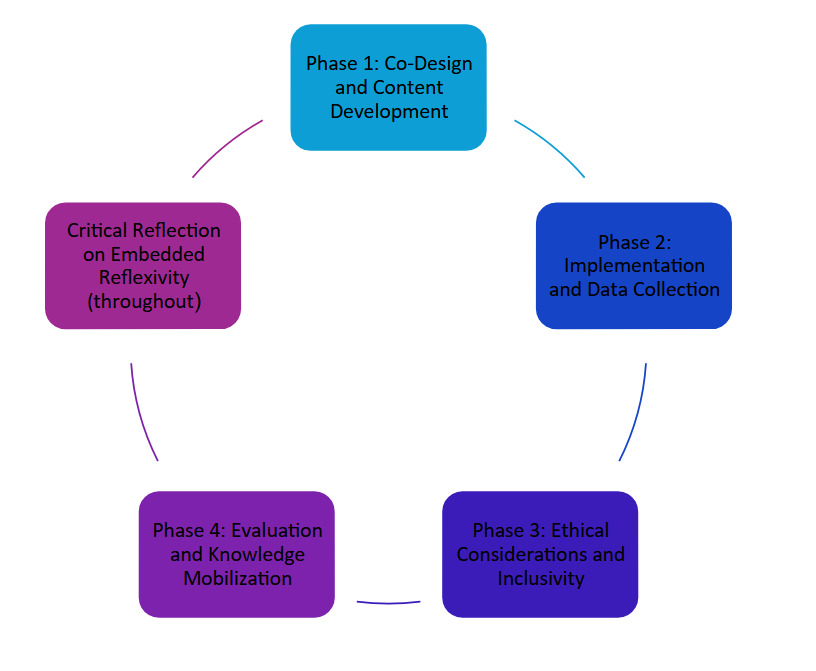

Below, we discuss the details of our young-adult-led participatory research study design and process, visualized in Figure 2. In each section we will highlight our participatory methods.

Phase 1: Co-Design and Content Development

The co-design phase served as the foundation for this youth-led research, with the recruitment and involvement of young adult co-researchers being central to its design and execution. One key participatory method was the inclusion of VOICE Champions—youth who provided feedback but were not part of the formal research team—as a deliberate effort to introduce multiple layers of accountability and reflection. We chose to engage this group rather than a separate youth sample due to the scope of the project. We also engaged in ongoing dialogue about our roles, privileges, and positionalities, both as student researchers and as individuals with varying degrees of access to academic and community platforms.

The co-design process involved both asynchronous and synchronous collaboration among the young adult researchers. Initially, researchers independently researched strategies for digital engagement, drawing on literature and examples from social media practice. They then met in synchronous meetings to discuss their findings, evaluate which strategies aligned with the study’s goals, and determine which were feasible to implement given the team’s time, capacity, and resources. Once content was developed based on these selected strategies, VOICE Champions were invited to provide feedback. Their feedback focused on the relevance, accessibility, and resonance of the posts. The VOICE Champions, with their own lived and living mental health experiences, participated in an iterative and reflexive process to shape the study’s priorities and content strategies. This phase was rooted in the recognition that youth-led research is not inherently emancipatory or advocacy-driven simply by virtue of young people being involved. The team critically interrogated the risks of tokenism and the possibility of replicating oppressive dynamics, even within youth-led frameworks.

A key point of reflection was that having youth representatives does not automatically equate to representing the diverse realities of equity-deserving young people. The research team was deeply aware that the power to lead also comes with the power to exclude, minoritize, oppress, or replicate hierarchies. This awareness informed a commitment to ensure that leadership and decision-making processes were as inclusive, representative, and participatory as possible. Reflexivity was crucial to ensuring that the team’s advocacy remained aligned with the needs of the communities they sought to serve.

Instagram and Facebook were chosen as the primary platforms for dissemination due to their widespread use, accessibility, and ability to host diverse content formats such as images, reels, and videos. Though Instagram is commonly used by young people, Facebook’s audience tends to be older (Auxier & Anderson, 2021). The reason Facebook was used was to target equity-deserving groups, Facebook was intentionally included to reach a broader range of equity-deserving groups, as its features, such as Marketplace and community groups, may engage different audiences than those typically found on Instagram.

While these platforms offer opportunities for broad dissemination, they have their limitations, including algorithmic biases that suppress certain content and inequities in access to digital technologies. These challenges underscored the need for a strategic and critical approach to platform selection. The study duration of five weeks was deliberately chosen to assess the feasibility of young-adult-led participatory research. As documented in the HEARTS study, significant structural and resource-related barriers exist for young adults to even be involved in participatory research, the least of which is to conduct independent research without substantial institutional support.

Many young researchers must balance multiple responsibilities, including academic commitments, employment, caregiving, and the management of health conditions, all of which shape their capacity to engage in sustained research efforts (Rao, Dimitropoulos, Milaney, et al., 2024; Rao, Jardine, et al., 2024). Recognizing that research often takes longer than anticipated, and that unfunded studies must account for logistical constraints, potential errors, and iterative learning processes, this timeframe was both practical and reflective of the realities facing young-adult-led and community-based researchers. Importantly, this study also serves as a model for assessing what may be realistically achievable for other youth-led research initiatives operating within similar constraints.

The content shared through the VOICE project focused on themes related to the HEARTS study and knowledge mobilization efforts. The content was collaboratively categorized into three thematic areas:

-

high-relevance, advocacy-driven posts designed to amplify minoritized voices

-

medium-relevance, general mental health content aimed at engaging a broader audience, and

-

low-relevance, trend-based posts intended to sustain attention through humour and relatability.

This categorization was the result of ongoing discussions about how young adults interact with social media and the types of content that could effectively balance relevance, depth, and reach based on how different types of content might interact with social media algorithms rather than based on a formal theoretical framework. For example, high-relevance posts focused on social justice and amplifying minoritized voices, such as sharing the importance of Patient Research Partner and BIPOC social media engagement, while medium-relevance posts addressed relatable topics like study tips during midterms or World Mental Health Day. Trend-based posts, such as memes and reels, served as entry points for broader conversations about mental health and equity. Further details can be found in Table 1, and examples can be seen in Figure 1.

Our collaboration extended beyond content creation. VOICE Champions were involved in ensuring the content resonated with the target audience by providing feedback and engaging in reflexive discussions about its relevance and accessibility. Recognizing the power of young adult networks, the team worked with student organizations, clubs, and advocacy groups to amplify the reach of their posts. This collaborative approach ensured that content was intentionally shared with communities most likely to benefit from it. For example, the research team contacted 26 student clubs, of which 10 actively reposted content on their social media platforms. This approach was mutually beneficial, allowing clubs to engage their audiences with relevant material while expanding the study’s visibility. Through this co-design process, the VOICE Champions redefined what it meant to lead a youth-led study, critically reflecting on their positionality and power while ensuring the research remained participatory, inclusive, and grounded in the lived realities of equity-deserving communities.

This phase highlights what we created—youth-centered, mental health advocacy content—and how we created it through a deeply participatory and reflexive process. Each decision, from platform selection to content categorization, was shaped collaboratively through real-time dialogue, shared leadership, and critical reflection on power and access. The process itself became a core outcome and offered insight for other young researchers seeking to lead their own community-driven, socially accountable research efforts.

Phase 2: Implementation and Data Collection

The implementation phase emphasized an iterative approach to knowledge mobilization, ensuring that the study was responsive to emerging insights. This phase maintained a participatory approach by actively involving VOICE Champions in decision-making processes around content creation, dissemination, and strategy refinement, ensuring that the community’s voices and perspectives continuously shaped the study’s trajectory.

Social media content was published on Instagram and Facebook. A new Facebook account was created for the study, while an existing Instagram account was used to leverage its established reach. Content was not advertised, but instead distributed organically, as per the Instagram and Facebook algorithms. VOICE Champions were actively involved in monitoring engagement and refining strategies based on feedback and analytics. This phase also incorporated reflexive practices, as the research team regularly evaluated the alignment between the study’s objectives and its evolving practices.

Quantitative engagement metrics, as detailed in Table 2, were collected using the analytics tools provided by the social media platforms. Metrics such as likes, shares, comments, saves, accounts reached, and accounts engaged offered insights into the reach and resonance of different content types. These quantitative measures were complemented by qualitative reflections from VOICE Champions, who provided context-rich feedback on the cultural, emotional, and social dimensions of engagement. For instance, one Champion reflected on how high-relevance advocacy posts fostered a sense of connection and liberation within their community, even when these posts struggled to achieve algorithmic visibility.

The study also examined the structural dynamics of social media platforms, critically engaging with the ways in which algorithmic biases privilege certain narratives while marginalizing others. Strategies to address these barriers included cross-posting content, optimizing hashtags, and collaborating with student organizations and advocacy groups to amplify visibility. These efforts were informed by a reflexive awareness of the limitations of digital platforms and the need to navigate these constraints creatively.

Phase 3: Ethical Considerations and Inclusivity

Ethical considerations were central to the study’s design, reflecting its commitment to emancipatory principles and trauma-informed practices. Despite being exempt from formal Research Ethics Board review under Article 2.5 of the Tri-Council Policy Statement by the Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics (2023) by using the secondary data provided by the social media platforms, the study rigorously adhered to ethical standards to ensure transparency, equity, and respect for all team members.

Moreover, trauma-informed practices were embedded to mitigate potential risks associated with online advocacy, such as doxxing, harassment, and emotional distress. Team members collaboratively developed the study, ensuring that there was full transparency about the study’s objectives and every person’s roles within it. Reflexivity was critical in this phase, as the research team continually assessed its practices to avoid extractive dynamics and ensure that co-researchers maintained meaningful control over the dissemination of findings.

Confidentiality was ensured by exclusively analyzing publicly available, non-identifiable data from social media platforms. This ethical approach upheld the study’s integrity but also aligned with its broader goal of activism and emancipation by reclaiming social media as a tool for equitable and inclusive knowledge mobilization, redirecting platform-generated data back to the communities it was initially drawn from.

Phase 4: Evaluation and Knowledge Mobilization

The final phase focused on evaluating the effectiveness of the social media strategies and their impact on knowledge mobilization. Reflexive practices were deeply embedded in this phase, as the research team critically analyzed engagement trends and the broader implications of their findings. There was not enough data to conduct any statistical tests; however, that is also a part of our evaluation of the process. These insights were contextualized through qualitative feedback from VOICE Champions, who highlighted the cultural and social factors influencing these outcomes.

Mixed media approaches, including memes, videos, and photo-based storytelling, were integral to the knowledge mobilization strategy. These formats were chosen for their ability to foster emotional connection, increase accessibility, and amplify minoritized voices. For example, photo-based storytelling highlighted the lived experiences of young adults navigating mental health-related disabilities, while reels and videos provided dynamic and engaging ways to disseminate research findings. Inclusive communication strategies were continuously assessed for their accessibility, representation, and cultural sensitivity. Reflexivity informed these assessments, as the research team and VOICE Champions collaboratively evaluated the alignment between the content and the priorities of the target communities. This iterative feedback loop ensured that the study’s dissemination practices remained participatory and relevant.

Critical Reflections on Embedded Reflexivity

We represent our process in a circle because it was continuously evolving, iterative and dynamic and throughout each phase, reflexivity served as a guiding principle, shaping the study’s methods and outcomes. The research team engaged in ongoing self-examination to challenge assumptions, recognize power dynamics, and adapt practices to better align with the study’s emancipatory goals.

Results

The findings from the VOICE study illustrate the nuanced interplay between quantitative engagement metrics and qualitative insights, emphasizing the structural challenges and opportunities inherent in using social media to engage equity-deserving youth and young adults. By employing an emancipatory, youth-led participatory methodology, the study sought to navigate the complexities of digital advocacy while maintaining its commitment to participatory knowledge mobilization.

The study’s advocacy-focused high-relevance posts demonstrated varying degrees of success in reaching audiences, particularly on Instagram. As shown in Figure 3, high-relevance posts reached more followers than non-followers during Week 2, while in Week 3, high- and medium-relevance posts exhibited similar trends. However, across the remaining weeks, the majority of posts reached non-followers, underscoring Instagram’s potential to expand beyond existing networks. Qualitative feedback from VOICE Champions contextualized these patterns, with one Champion remarking, “I liked the mix of single-page posts and carousel posts, as it added breaks between content-heavy posts.” This feedback highlights the importance of content diversity in sustaining engagement.

The structural barriers imposed by these algorithms are further illustrated by the disparity in engagement levels across content types. As shown in Figure 4, high-relevance posts elicited deeper interactions compared to low-relevance posts, but the reach of advocacy-driven content was often constrained by platform dynamics. This was corroborated by qualitative reflections, which highlighted the need to balance the urgency of advocacy with the constraints of visibility. One VOICE Champion observed, “some posts were a bit text-heavy, and I’m not sure if everyone necessarily is going to read them.”

Medium-relevance content, focusing on general mental health topics, offered a practical middle ground. As illustrated in Figure 4, these posts maintained steady interactions across weeks, engaging both followers and non-followers. Qualitative feedback reinforced these findings, with Champions highlighting the relatability of posts addressing study habits and mental health awareness, with one Champion sharing, “I would look at more of this content.” Additionally, some Champions noted that the language used in these posts made mental health topics feel more approachable, reinforcing the importance of accessibility in content creation.

Reels and static posts performed differently in terms of engagement and reach. Figure 4 reveals that reels and posts generated similar overall interaction volumes, but posts engaged a more diverse audience. The number of unique accounts reached by reels remained lower than that of static posts, as shown in Figure 5-6, suggesting that while reels attract immediate attention, static posts foster sustained and meaningful interactions. This aligns with qualitative feedback, where Champions emphasized the importance of clear, accessible messaging. However, longer reels were noted as less effective in maintaining viewer interest, with one Champion commenting, “due to TikToks, I find that I have a harder time listening to a longer video, especially without visuals.”

Facebook presented additional challenges, as highlighted in Figure 7, where the overall reach of posts was significantly lower than on Instagram. The study’s Facebook engagement was further constrained by external factors, including a temporary platform-imposed restriction that limited the account’s functionality. This restriction, coupled with limited responses from student clubs and organizations, is reflected in the lack of significant interactions, as shown in Figure 7. These findings underscore the broader limitations of corporate social media platforms for equitable knowledge mobilization.

Quantitative metrics, such as those in Figures 2-9, demonstrate how high-relevance posts and reels can extend the reach of advocacy efforts, while qualitative insights emphasize the need for culturally responsive and accessible content to foster meaningful engagement.

Discussion

The findings from the VOICE study demonstrate both the potential and the constraints of our participatory, youth-led digital knowledge mobilization. While social media offers opportunities to reach equity-deserving and hardly reached youth and young adults, it also introduces significant structural barriers such as, algorithmic suppression, corporate control of digital platforms (Hearn, 2008; Khamis et al., 2017), and the exclusion of young people who opt out of social media. These findings contribute to the growing literature on emancipatory and activist research methodologies by illustrating the importance of positioning young adults as leaders in knowledge creation; however, the study also challenges assumptions about social media’s ability to democratize knowledge.

By employing a co-created and iterative research approach, this study sought to move beyond extractive models of knowledge production, ensuring that young people shaped not just the research itself but also the ways in which knowledge was shaped, contoured, performed, communicated and ultimately mobilized. The results complicate the notion that increasing reach on social media translates into deeper engagement. While Instagram reels demonstrated the highest visibility, qualitative feedback from VOICE Champions indicated that reach alone did not ensure meaningful interaction. High-relevance advocacy posts, while central to the study’s goal of amplifying minoritized voices, did not resonate as much with audiences—as per quantitative and qualitative feedback—compared to medium-relevance posts, which focused on relatable topics such as study habits and general mental health awareness.

The study encountered institutional and structural barriers to online engagement. The temporary restriction imposed on the HEARTS Facebook account serves as an example of how corporate platforms exert control over what knowledge is made publicly available. These limitations raise ethical concerns about the over-reliance on social media for participatory knowledge mobilization, particularly when platforms are not accountable to the communities they claim to serve. Further, the study found that engagement patterns were highly dependent on platform affordances. Facebook’s outreach efforts were hindered not only by the account restriction but also by demographic shifts.

Facebook’s user base skews older and tends to engage differently with content than Instagram’s younger audience (Auxier & Anderson, 2021). While Instagram allowed for broader audience exposure, this visibility was contingent on the type of content being disseminated. Advocacy-oriented posts faced greater limitations, while trend-based, lower-relevance posts gained wider reach but lower substantive engagement. This raises fundamental questions about the role of social media as a space for political engagement versus passive consumption. The study also challenges the idea that social media can replace face-to-face community building. One Instagram post we created before the study, an invitation to a Town Hall post, which encouraged offline engagement, was one of the highest-performing posts despite being shared when the account had fewer followers. This suggests that social media knowledge mobilization is most effective when integrated with real-world action rather than being treated as a standalone engagement strategy.

Moreover, the study raises concerns about who is left out of social media-driven research dissemination. While digital platforms provide an accessible space for many, they do not reach youth who lack stable internet access, actively avoid social media due to privacy concerns, or engage in alternative digital spaces outside mainstream platforms. This suggests that social media-driven knowledge mobilization, even when its intentions are to reach equity-deserving groups, if not critically examined, can unintentionally reproduce the same exclusions it seeks to address.

One of the key challenges identified in this study is the fundamental difference between research-focused content and the broader culture of social media engagement. Influencers and digital activists often rely on personal branding and highly curated personas to maintain audience engagement (Khamis et al., 2017). Research initiatives, however, are driven by ethical considerations, transparency, and a focus on substantive knowledge-sharing rather than aesthetic appeal or algorithmic gaming. This study found that research-focused content does not always align with the fast-paced, attention-driven nature of social media platforms. For instance, while reels had broad reach, they did not consistently maintain audience interest. Memes and humour-based posts, which were included as a strategy for engagement, also received mixed feedback. While some posts attracted new viewers, others were seen as niche or difficult to interpret without prior knowledge of research or mental health discourse. This highlights an important tension between accessibility and depth in digital knowledge mobilization. While simplifying complex research for social media is necessary, there is a risk of diluting critical insights in favour of the broad appeal. The findings suggest that perhaps hybrid approaches which integrate digital dissemination with in-person engagement may be the most effective way to translate knowledge into meaningful action.

Strengths and Limitations

This study contributes to the field of young-adult-led participatory knowledge mobilization by demonstrating the potential of youth-led digital advocacy while also identifying key limitations that must be addressed in future research. One of the primary strengths of this study is its young-adult-led participatory co-design, in which young adults with lived and living experience actively led and directed the research process. Moreover, by engaging VOICE Champions in co-designing and evaluating knowledge mobilization strategies, the study ensured that the content was shaped by the lived experiences and perspectives of equity-deserving young people. This model of engagement challenges traditional research hierarchies, demonstrating the capacity of young adults to produce and disseminate knowledge in ways that are more accessible and resonant with their peers.

Despite these strengths, the study also highlights the structural limitations of using social media as a tool for participatory research. One significant limitation was the difficulty in tracking lurking, where individuals view content but do not interact with it through likes, comments, or shares. This is particularly relevant for mental health research, where stigma may deter young people from publicly engaging with advocacy-related content. Future studies should consider alternative methods for capturing qualitative forms of engagement, such as private message interactions or offline discussions inspired by social media posts.

Additionally, the study faced constraints in demographic data collection. Due to Instagram’s minimum follower requirement for account insights, the research team was unable to analyze audience characteristics such as age, gender, or geographic location. This limited the ability to assess whether certain demographic groups were more or less likely to engage with the content. Future studies could explore collaborations with established youth organizations or leverage existing digital research infrastructures to address this gap. Finally, this study did not reach youth and young adults who remain offline or actively disengage from social media. Digital knowledge mobilization, while increasingly necessary, cannot replace other forms of outreach that target young people who lack internet access or deliberately avoid social media due to concerns over privacy, misinformation, or mental well-being. Future research must consider multi-platform approaches that include offline engagement strategies alongside digital dissemination.

Implications for Future Young Adult (or any age) Activist Researchers

The findings from this study provide important considerations for future researchers seeking to use social media as a platform for activist and emancipatory knowledge mobilization. First, this study demonstrates that traditional engagement metrics are insufficient for evaluating the impact of advocacy-driven content. Likes, shares, and comments do not fully capture the depth of engagement, particularly for sensitive topics like mental health and social justice. Future researchers should integrate alternative measures of engagement, such as private message responses, qualitative feedback, and real-world actions inspired by digital advocacy.

Second, the study reinforces the importance of multi-modal content strategies. Future studies should not rely solely on text-based social media posts but should integrate a variety of formats: video, interactive content, and infographics—to accommodate different learning styles and levels of digital literacy. The inclusion of humour and trending content was found to be useful for attracting attention, but it must be balanced with substantive and actionable knowledge-sharing.

Third, researchers must critically engage with the structural barriers imposed by social media platforms. Algorithmic suppression and corporate platform policies create unequal conditions for knowledge mobilization, disproportionately affecting advocacy-driven research. Future efforts should experiment with alternative, non-commercial digital platforms or explore decentralized knowledge-sharing models that do not rely on the visibility granted by major corporate social media companies.

Finally, the study highlights the need for sustained relationships with youth organizations, community leaders, and grassroots movements. Social media alone is not enough to foster long-term engagement; researchers should co-create knowledge with communities rather than simply using social media as a one-way dissemination tool. This includes fostering relationships beyond the study period, ensuring sustainability and that young people are co-owners of the knowledge produced.

Conclusion

The VOICE study illustrates both the possibilities and constraints of participatory digital knowledge mobilization. While social media offers an accessible and scalable platform for engaging young people, it is not a neutral tool. Its current structures privilege certain types of content while suppressing others. Despite researchers’ best intentions to reach diverse audiences, algorithmic barriers, platform restrictions, and the challenges of online engagement continue to shape what knowledge is visible, who engages with it, and how it is mobilized. These findings reinforce the necessity of critically rethinking how research is disseminated and who it is designed for.

Participatory, activist research must move beyond surface-level engagement metrics and instead center the voices, needs, and priorities of the communities it seeks to serve. As digital knowledge mobilization evolves, researchers must be intentional in designing strategies that not only work within existing platforms but also challenge their limitations. This study highlights the need for alternative and community-driven knowledge dissemination models, ones that resist corporate control, foster deeper engagement, and prioritize youth-led, equity-driven approaches. As social media landscapes continue to shift, the role of researchers is not only to adapt but to actively interrogate and transform the conditions under which knowledge is produced and shared.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of the VOICE Champions, Alyssa Ma and Tiara Gonsalkoralage, whose lived and living experiences and insights were integral to this study. Their leadership in refining knowledge mobilization strategies ensures that research remains relevant, impactful, and young adult community-driven.

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any external funding.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AI use

This manuscript was developed with the assistance of AI tools, including ChatGPT, for the purpose of refining language and creating APA citations. No AI-generated content was used to develop original ideas or formulate arguments, and are all the authors’ original work. This disclosure is made to ensure transparency.

Author Contributions (CReDiT Taxonomy)

Conceptualization: Alyshah Pirwany, Sandy Rao

Methodology: Alyshah Pirwany, Lhezel De Quina, Laetitia Satam, Ysabelle Tumaneng, Sandy Rao

Data Collection: Alyshah Pirwany, Lhezel De Quina

Data Analysis: Alyshah Pirwany, Sandy Rao

Writing – Original Draft: Alyshah Pirwany, Lhezel de Quina, Laetitia Satam, Ysabelle Tumaneng, Sandy Rao

Writing – Review & Editing: Alyshah Pirwany, Lhezel De Quina, Laetitia Satam, Ysabelle Tumaneng, Sandy Rao

Supervision & Guidance: Sandy Rao (direction, conceptual support, methodological input, mentorship)

Project Administration: Alyshah Pirwany

Visualization & Knowledge Mobilization Strategy: Alyshah Pirwany, Lhezel De Quina, Laetitia Satam, Ysabelle Tumaneng, Sandy Rao