In recent years there has been increased emphasis on co-design and stakeholder involvement in research (e.g. Blomkamp, 2018; Zamenopoulos & Alexiou, 2018). For example, UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), a primary funder of UK research, states that: “Research benefits from including people from outside the research community in a process of shared learning…. Involving individuals with a stake in the project who are not researchers can enhance the quality of the research and help it to bring about positive change for society and the economy.” (UKRI, 2024). Similar statements are associated with other funders such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK), National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and National Institutes for Health (USA) (Bird et al., 2021; Kaisler & Missbach, 2020; Morley et al., 2024; Slattery et al., 2020). However, in practice projects vary enormously in the extent to which they successfully engage with inclusive and participatory research practices. Too often these are ‘tick box’ consultations, or partnerships that use participants’ ideas and experience without acknowledgement. Other projects are better at involving representatives of communities in research design and data collection, but then inadvertently exclude them from the analysis and interpretation of the data that represents them. Even UKRI’s own examples of ‘co-production’ are limited to “identifying research questions, design and priority setting, governance, co-delivery of research activities, communication of key findings and involvement in knowledge exchange” (UKRI, 2024). The implication would seem to be that data analysis and interpretation are the purview of researchers and represent an area where communities are not expected to contribute. It therefore seems that whilst co-production is valued in principle, there are underlying assumptions about the limits that researchers can place on that participation, and narratives that justify participant exclusion as necessary in the interests of rigour or practicality.

One example of this in action can be observed in the helpful paper by Godrie et al. (2020), who describe a framework for evaluating participatory research with communities that draws on notions of epistemic justice and co-production. The focus is on the immediate mechanics of creating ‘co-learning spaces’ as a participatory methodology, such as considering the title of the project and why it was so named, reflecting on who initiated and inputted into research questions, recognising different types of knowledge and identifying and seeking to reduce inequalities. However, the writing and editorial control of the published work was allocated only to academics as:

“it was clear from the outset that putting them [non-academic partners] in a position to write parts of the article was an unfair burden because, unlike the academics, they were not paid to do so, did not have the appropriate training and could not spend as much time on it” (p9).

The paper also acknowledges a failure to financially compensate participants appropriately for their contributions to the work and the frustration of one participant that their views were not accounted for by the person leading the discussion. There was also a lack of clarity on how the experiences and accounts shared by participants were synthesised – this appears to have been led by the coordinators and facilitators of the meetings (thereby arguably replacing one set of power structures with another) and the resulting document was only offered for ‘additions/validations’ by the other participants. Overall, the recommendation from their framework that existing inequalities should be addressed and reduced was not enacted in the project that underpinned this recommendation, but the authors were open and honest about the processes and learning that occurred as part of this project.

It seems clear that within social science, and perhaps in other areas too, we would benefit from reflection on how we undertake work that has implications for specific people and communities. We need better methods that afford non-academic partners more involvement in and ownership of the data analysis and interpretation phases of research. This paper begins with a levelled series of scenarios designed to provoke reflection on how communities are (and could be) engaged in research, and is followed by an account of how an existing collaborative tool can be used for effective co-design with diverse community partners and participant-led data analysis.

Reflecting on Community Participation in Research

In Table 1 we present ten simple scenarios that capture different forms of community participation in social science research, describing the types of contact researchers can have with community partners, the nature of that partnership, and the outcomes from that research. These scenarios together are intended to act as a provocation for reflection on the ways in which we all engage with non-academic partners in the scope of our research endeavours. Our individual and collective reflections on these different conceptualisations of research partnership can be used to understand inclusion in the context of any research where communities hold first-hand knowledge and experience of phenomena of interest. In offering this provocation, we acknowledge the value in reflecting on and holding ourselves accountable for the practices we habitually adopt within our disciplinary traditions and aim to improve upon these.

In the first example (Level 1), there is research where no engagement with communities or users is undertaken – this is often characteristic of theoretically-driven research, or of research where the researchers feel that they know all that they need to know from the extant literature about the communities they are discussing. In the social sciences, the difficulty with such work is that it is likely to be rooted in a literature that has historically excluded those communities from the research process, thereby reproducing and even magnifying existing epistemic inequalities and hermeneutical injustice by excluding groups and their experiences from academic accounts, denying them the ability to access or coin language that can account for their experience and thereby influence future scholarship in the area (Fletcher, 2024; Fricker, 2017). Similarly, at Level 2, we describe research undertaken without input from those being researched, but where research findings are then promoted to relevant communities for adoption or endorsement. The underlying assumption here is that the community will be grateful for the insights provided by the work, and that the researchers have an accurate understanding of the issues and problems experienced. Although this may be the case, such assumptions represent weaknesses in the research process that could undermine the validity of the work and its potential for application or adoption.

The scenario described in Level 3 is in many ways one of the most commonly observed approaches to community participation. Here, the work is designed based on prior research, but an advisory group is formed to comment on the research process and outcomes. There is scope for advisory boards to positively impact research and as such they are a welcome inclusion in any project. However, it should be noted that their impact can be significantly limited in the cases where the project has already been designed (and often signed off by a funder). The inclusion of an advisory group, if not built into the project in a meaningful way, can represent a performative level of involvement, offering the impression of quality assurance and user engagement, if they are invited to contribute only at points in the research determined by the academic team.

The next scenario (Level 4) intentionally offers community partners the chance to input into the proposed design and execution of the project before it commences. However, the engagement could be seen as tokenistic because the engagement with partners does not continue beyond these early consultations, and the community is informed of outcomes only at the conclusion of the project. The account given in Level 5 may be seen as stronger, as here we see a greater attempt at collaboration, with community partners actively leading the work including many aspects of data collection. However, the data are analysed without participants or partners, and the outcomes of the research remain in the ownership of academics who go on to author outputs and resources based upon it. Community input is more extensive at this level, which is significant and positive. However, if the work and labour invested by that community is not formally recognised or reciprocated in some way that is mutually agreed at the outset, they are more likely to be disenfranchised from the project outcomes. For many, the scenario described in Level 5 of Table 1 would be viewed as an exploitative arrangement.

A related point for reflection is the tension between researcher-led analysis vs participant-led analysis. This is a particularly important point in the case of qualitative research methods, where subjectivity is recognised as a necessary feature of such approaches, but researchers assume a level of authority over the ‘correct’ ways to interrogate data and thereby may inadvertently promote their account over that of their respondents. Disciplinary demands for ‘rigour’ tend to result in researcher ownership of the analytic process. Our purpose with the provocations outlined here is to prompt personal and collective reflection on the impact that may have had on our disciplinary knowledge to date, and to argue that there is a real need to work in partnership across all phases of the research process to prevent misrepresentation or adherence to accepted theoretical accounts. How researchers and external partners choose to come together to understand the phenomenon of interest is something that needs to be discussed, and suitable methods explored that enable participant-led analysis.

At Level 6 we see a case where there are sincere attempts at co-design, with fundamental ideas and methods being jointly arrived at. In this scenario, however, the research itself is undertaken by the academic researchers, who then feed back to their community partners at the end of the project. The problem that can arise here is that the outcomes from the research are controlled by the academic partners, who then are in a position (if they so choose) to levy charges or place other restrictions on the applied use of the research. For example, we see this in the case of educational research, where work may be undertaken with teachers or schools in order to develop training resources or interventions to support teaching and learning. Instead of these outputs being made freely available to schools and teachers, they are commercially exploited by either the academics or universities who employ them, and the resources sold back to teachers and schools. This is often mitigated by at least ensuring that those partners who were directly involved in the development are able to access the resources freely or at minimal expense. Without such considerations, this form of partnership can be seen as exploitative, even representing a form of intellectual theft. Even in this case, the wider educational community may not benefit from the learning obtained, and so in these cases effort is needed to consider how the wider community might access learning from the project. In such instances open access publication of papers can help to bridge this gap, as do time-limited free access to any commercially available resource.

In the Level 7 scenario we see similar degrees of co-design as in Level 6, but this account represents a stronger example of participation, as the partnership is actively maintained throughout the project, including during the interpretation of research findings, and outcomes are jointly owned and freely shared. The inclusion of participants in data analysis is, as discussed earlier, significant insofar as it is still unusual practice in social sciences at the time of writing. More common is the model where academics undertake data analysis and then consult with non-academic co-researchers on whether the interpretation of the data is felt to be valid (e.g. as in Godrie et al., 2020). However, the extent to which this process is allowed to influence the final interpretation of the data is not always clear. For this reason we advocate for approaches to data analysis that enable participants to interpret their own data either individually or collectively. The second half of this paper will go on to explore one approach that can enable this.

At Level 8 we see an account of participatory engagement of partners in the context of an idea that is proposed initially by academics. As MacAulay et al. (1999, p. 774) note:

“Collaboration, education, and action are the three key elements of participatory research. Such research stresses the relationship between researcher and community, the direct benefit to the community as a potential outcome of the research, and the community’s involvement as itself beneficial.”

In the scenario outlined, the work is codesigned, and then largely led by the community partner with appropriate support by academics. Data are analysed collaboratively, outcomes jointly owned, and the community is able to use the research for their collective benefit. In this account the academics are the catalyst for action, but beyond that responsibility and participation is shared. The scenario described in Level 9 is identical to that in Level 8, but is presented as better option in our provocation because the idea arises jointly from both partners. This is most likely to occur in the context of a mature partnership where the academic team and community partner are in regular contact (both informal and formal) over an extended period and where challenges or questions are jointly encountered. This emphasises the importance of developing and maintaining enduring relationships in order to achieve work with the greatest potential for coproduction and impact.

The Level 10 scenario is located at the highest level of participation, because the work is initiated by a community who approach the academic team for support and expertise when required. The extent of that support may fall on a range from minimal (perhaps providing access to some form of resource that enables the work to take place in the way necessary) to more substantial (sharing the work of data collection or analysis, or cocreating resources). In this model academic partners are secondary partners. Crucially, the community deploys outcomes to enable community transformation, details of which may be shared with academic partners. This form of partnership is placed at the highest level of our provocation because it represents the strongest challenge to academic conventions on working in partnership – handing over much of the control of the project to the community it is centred upon, prioritising community need over academic outcomes. Such approaches are currently most often observed in the context of some forms of commissioned evaluation of community-led initiatives, where academics are deployed as resources in service of a project that is likely to have originated as a response to a practical challenge faced by a group, rather than as a research project as such.

Challenges in Adopting Inclusive Participatory Research Practices

One of the barriers to achieving participatory research practices is that often we lack well-defined and developed inclusive approaches to effective co-design and participatory data analysis. Co-design is approached in many different ways and whilst that is not necessarily an issue per se, being seen to ‘do co-design’ means that sometimes limited attention is paid to how inclusive such attempts are. For example, social dynamics are such that perceived hierarchies operate even in the context of focus groups, and academic partners too often get the final say over the formulation of the project design. MacAulay et al. (1999) note:

“Participatory research attempts to negotiate a balance between developing valid generalisable knowledge and benefiting the community that is being researched and to improve research protocols by incorporating the knowledge and expertise of community members.”(p774).

The phrasing here acknowledges the prevailing assumption that community involvement in research represents a threat to scientific rigour that has to be managed. Similarly, as noted at the start of this paper, there is an underlying assumption that non-academic partners are not expected to input into data analysis (UKRI, 2024), seemingly because only research teams hold sufficient analytic expertise and understand rigour, and it is noteworthy in also being omitted from MacAuley et al.'s (1999) list of what researchers should negotiate with community partners (p777).

References in the literature to ‘participant researchers’ often refer to researchers who elect to participate in research as part of the phenomenon or group being studied (e.g. Wainwright et al., 2018), rather than examples of community members acting as researchers with equal responsibilities to academic colleagues, although ‘citizen science’ is growing in popularity. So, we find examples in the literature of where researchers train ‘community researchers’ on the research process to enable them to be more like academics (e.g. Kellett, 2005; Robinson et al., 2024), and which can inadvertently render them less like the communities they represent, therefore undermining the benefits of their involvement as community representatives. Interestingly, we also find examples like Pope (2020) who describes the process of redesigning their research as it evolved to move it from a traditional model to one where participants were repositioned as co-researchers, fundamentally changing the nature of the project, including the reinterpretation of data that had been initially coded by Pope. However, even in this example Pope retained the role as primary researcher because the research represented their postgraduate dissertation work, and there was no mention of transformation or action towards social justice arising from the work as is normally expected from participatory enquiry (Fine & Torre, 2019).

More recently, Robinson et al. (2024) give an account of their approach to citizen-science in the context of transdisciplinary environmental research. Their work includes many strong aspects, including the honest reflection on the difficulties inherent in participatory work including differences in understanding of how to formulate research, the need to carefully broker and strengthen community partnerships, and the challenges of delivering research in the context of community collaboration and citizen research. In relation to outcomes and co-creation of research, they note:

“However, at the beginning of any collaboration, it is important to reflect critically on whether a co-created approach is appropriate…In many instances a key challenge refers to academics’ primary commitment to conducting and finishing the research rather than realising sustainable impact afterwards.” (p12).

This final step of transformational action, is mainly (if not exclusively) seen in the context of critical participatory action research (CPAR), with examples like Fine and Torre (2019) providing a account of how CPAR can provide an inclusive and accountable model of participatory research which results in necessary positive action for communities. From a social justice perspective, we challenge Robinson et al’s view that co-creation of research is not “suitable or necessary in all contexts and co-creation should not be considered the superior option” (p12) because it requires academics to relinquish control of research outcomes and be open to the need to put community needs above those of academic agendas. Rather, we maintain that our disciplinary knowledge is poorer as a consequence of a history of excluding community expertise from academic accounts, and we have to take responsibility for the missed opportunities for deploying research in the service of the communities we work with.

CoNavigator as an Approach to Co-Design, Data Collection and Analysis

We have seen that there is still a need for methods that will enable participants not just to contribute to research questions, data collection and analysis, but to have full control over how data elicited is analysed and over the resulting models built from such an analysis. We argue that a tool originally developed to enable interdisciplinary collaboration between academics (Co-Navigator) has additional utility as a procedure for enabling equitable inclusion of participants in the analysis and interpretation of research data collected in group contexts.

CoNavigator is a hands-on tool for interdisciplinary collaboration, developed in 2016 by David Earle, Line Hillersdal and Katrine Ellemose Lindvig (Lindvig et al., 2018). CoNavigator combines physical elements with a series of configurable steps, according to the needs of a session. It was originally designed and developed to mitigate challenges in interdisciplinary teaching and collaboration identified by Hillersdal and Lindvig in their research at the University of Copenhagen (c.f. Lindvig & Hillersdal, 2019; Lindvig & Ulriksen, 2016). Here, it was clear that there was a need for a method or tool that would facilitate collaboration in a way where intersections of disciplines, expertise, gender and agency became assets instead of barriers. Drawing on design thinking from the creative industries and based on findings from ethnographic and educational research, the aim was to facilitate what Habermas (1981) called undistorted communication: dialogue that is free from manipulation or power dynamics, enabling all participants to be open and honest in a context of respect. Rather than moving directly to solution-based thinking, CoNavigator methodology ensures that the most time in a session is given to building up a clearer, shared understanding of each participant’s point of view concerning a given theme or problem, and showing how that point of view aligns (or does not align) with those of other participants. CoNavigator’s key stages are: “1: What is it?”, “2: What ought it be”, and “3: What to do”, with Stage 1 typically taking up at least 50% of the session’s allotted time. Crucially, in terms of the model of inclusion discussed earlier, the ‘what to do’ phase of activity centres on concrete actions to be taken forward by participants in the CoNavigation.

What makes CoNavigator an efficient tool for interdisciplinary education and collaboration, also benefits users if we reframe it as a research method. Below, we unpack how CoNavigator works for research as a tool that enables the generation of data from individual respondents who are part of a group, and then subjects those ideas to a form of collective data analysis undertaken by that group of participants in real time. We discuss how it helps to increase inclusion and enables participants to undertake qualitative analysis of their group’s data. The data are individual responses to a broad topic of revelance and interest, which are then collectively interrogated, grouped and organised into a three dimensional ‘map’ which represents key themes and concepts, how they relate to each other, and what strengthens or threatens the strength of those connections. These maps are captured graphically at the end of the session, alongside the participants’ group account of what is on their map, and what they discussed when building it. The map represents the outcome of the data analysis, and the oral account is used only contextualise what is on the map and why. Quotes from the narrative can be provided to validate the final narrative that is used in any report, by using verbatim explanations from the participants themselves, rather than relying on non-participant voices to editorialise the account.

Overview

CoNavigator is a collaboration tool. To run a CoNavigation, a physical ‘toolkit’ is used, comprising tiles, coloured pegs, cubes and strings (see Figure 1). These elements are systematically used at key steps during the process to record thoughts and ideas, indicate areas of shared interest, areas of particular significance, and connections between those ideas. What results over the course of around 2 hours is the construction of a three-dimensional ‘map’ of the topic under discussion, which represents the participants’ collective reflections on experiencing and understanding that topic. Aside from the toolkit itself, CoNavigator includes instructions for facilitation, which can either be carried out by an assigned facilitator, or by using a specially designed App which can prompt the participants to move through the steps without the need for a facilitator to be involved at all, therefore removing academic voices from the data collection and analytic process entirely, if desired.

CoNavigator encourages groups to collaborate ‘spatially’, using the tactile elements which require coordinated hands while building a shared narrative. Collaboration is focused on the tool’s elements using gestures, voices and hands, which can improve collaborative outcomes (Tversky & Jamalian, 2021; Zheng & Tversky, 2024) . There are no visual cues on the tiles (such as lines or squares) – each tile is a literal blank slate, allowing the individual to add words, symbols, icons or glyphs, and combine with the other participants’ tiles. Colour is reduced to a minimum and used only to denote each individual’s contributions via the use of coloured pegs used to annotate the tiles at key points in the process. To help mitigate some of the imbalances in the group dynamics, sessions are designed to follow an alternating series of individual and collective steps.

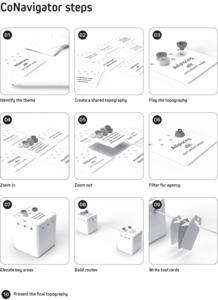

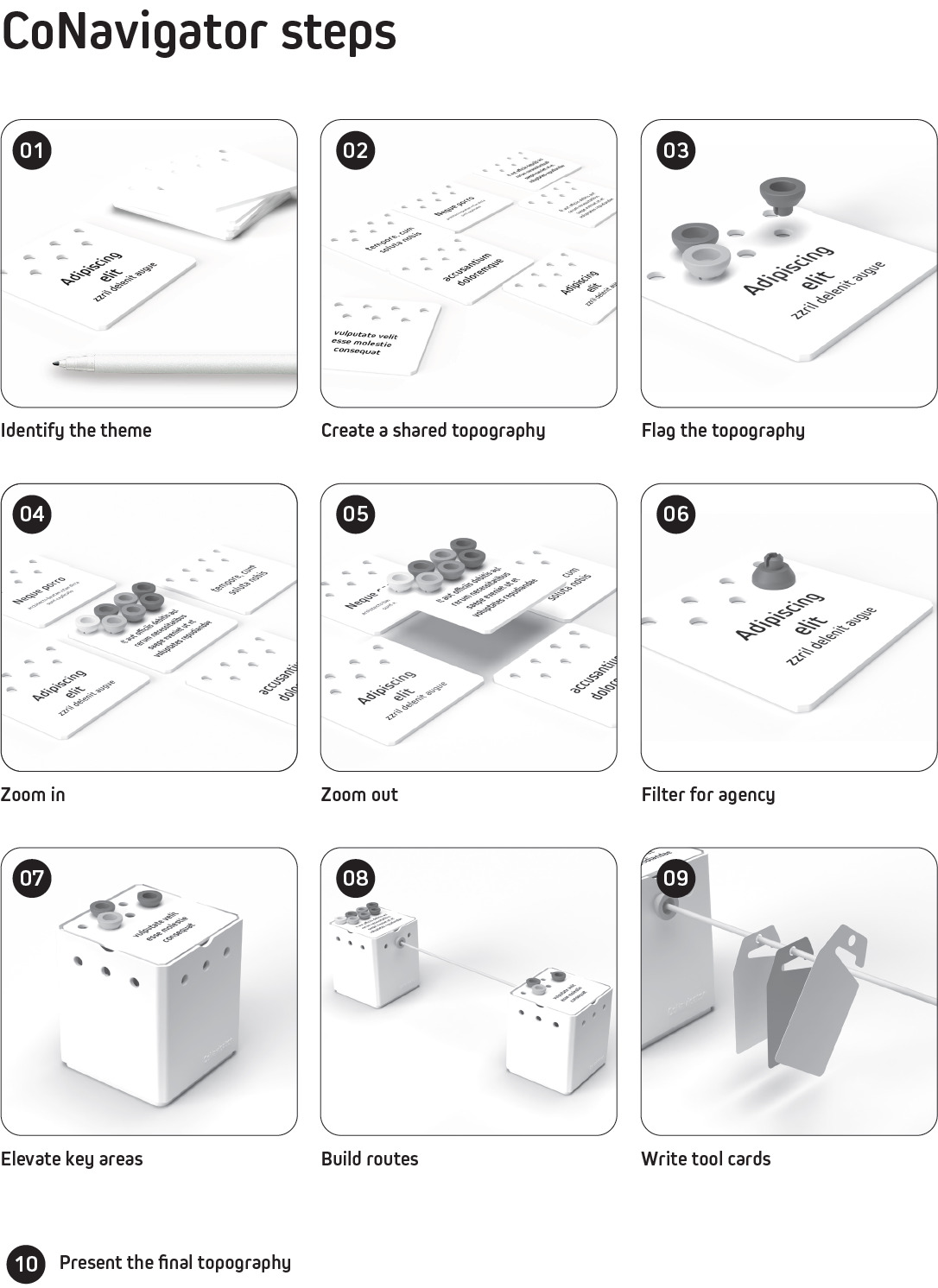

In a typical ‘exploratory’ CoNavigation the steps are as follows:

-

Identify the Theme. Once the group has been provided with the topic to be considered, participants are prompted to consider their own thoughts and reflections, and to silently record each one on a tile. Thoughts are recorded privately so participants do not feel under pressure to follow or align with other participants’ views.

-

Create a Shared Topography. Participants lay their tiles down on the table, often elaborating on what they have written on their tile for the benefit of others in the group. Group members begin to move and position the group’s tiles into clusters of related ideas to form ‘islands’ of related concepts.

-

Flag the Topography. Each participant is then allocated a colour and given pegs of that colour that attach to the tiles. Participants individually review the tiles that form the map so far, and place their pegs on the tiles that they personally see as key to the topic under discussion. They can select as many or as few tiles as they wish to tag in this way. At this stage some tiles will have many different coloured tags attached, and others will have none (see Figure 2).

-

Zoom In. The group is then invited to look at the tiles with the most tags, and participants who selected those tiles are invited to indicate why they tagged it and what it means for them, and those reasons are recorded on more tiles which are then added to the map. This step encourages participants to add more context (disciplinary, personal etc.) to an idea that the entire group appears to agree is central. This can reveal complexities and nuances between the participants’ diverse backgrounds as the reasons underlying this apparent consensus are typically quite diverse. This extra contextualisation also leads to new insights and avenues of thought and analysis that might otherwise not have been open for discussion.

-

Zoom Out. Next, the tiles with no tags in are reviewed, and participants are prompted to consider whether they are comfortable with those areas being minimised. Individuals’ reasons for this relative lack of importance are clarified and those reasons added to the map. The group may agree to remove these tiles from the map, or to move them to a place on the map away from the main ideas of interest to the group.

-

Filter for Agency. (This step is optional, as it may not always be relevant to the topic under consideration). Once participants have negotiated a shared map, and individually flagged which elements are key to the theme or problem, they are then challenged to assess their own selections in terms of how much agency they have in effecting change or acting upon that particular element . As this is done individually, the process demonstrates the perceived agency each participant has – there are often differences in opinion as to who has or does not have agency in certain elements. If there are elements which most participants have flagged as essential, but no-one has any agency over (so-called “agency-deserts”), they can be discussed in more depth. It might be agreed that, because there is nothing that can feasibly done about it, it can be left as it is. If it is agreed that it is necessary to find a way to assign agency to the element, this tile is elevated (see Step 7).

-

Elevate Key Areas. Each participant is handed a cube and instructed to select just one tile from the map that they personally see as the most important. Any tile can be selected, regardless of how many tags are in it. They then elevate that tile by placing it on the cube they have been given. If more than one person selects the same tile, the cubes are stacked one on top of the other to create a taller structure.

-

Build Routes. The next step requires participants to discuss how the elevated tiles relate to each other (and other key areas of the map that may not be elevated). Strings are used to create physical connections between the related ideas. The building of these ‘bridges’ is designed to be carried out by two individuals, encouraging synchronised physical co-operation, using hands (see Figure 3).

- Write Tool Cards. Participants reflect on how those bridges might be strengthened, as well as what weakens or undermines those connections. Those actions, people or concerns are recorded on tool cards and attached to the bridges. The actions recorded form the basis of next steps to address potential solutions to the problems identified when mapping the topic (see Figure 4).

- Present the Final Topography. Finally, participants are invited to talk through the map that they have constructed, and these narrative explanations are captured, alongside photographs of the map. These are then used to construct a diagrammatic version of the map that they have created (a ‘flat map’, see Figure 5) enabling a consideration of the spatial relationships indicated between concepts.

Building maps using the basic cardinal points (north, south, east and west) on horizontal and vertical plans, and connecting tiles are basic building blocks of spatial and gestural thinking. Participants tend to treat information placed on the horizontal plane neutrally – meaning there is no inherent privileged direction amongst the tiles that are on the same plane. In many CoNavigator sessions, there can be a tendency for the tiles with the most tags and bridges to be placed in the middle of the map, while the less populated tiles are pushed to the edges of the table. But the cardinal direction of these peripheral tiles is generally not significant. The vertical elements are more important, however. Pegs on top of the tiles endow them with more importance, but this is done in a democratic way, with one peg per tile per person. The elevated tiles on the cubes are the most important tiles on the map but are each chosen by individual participants as the concept they themselves would like to focus on, regardless of how many others may have tagged it.

As noted earlier, the map constitutes the analysis, akin in some ways to more traditional forms of thematic analysis in which concepts are grouped and consideration given to how the concepts relate to each other, which are primary themes, and which are secondary. However, the mapped themes are directly generated by participants in real time, not determined as a result of analysing the talk of the participants, thereby removing the filter of the researcher’s lens, or any emphasis on how many times it recurred throughout the conversation. The recording of the final presentation where participants explain what is on their map and why is done to enable the participants to contextualise the map in the final report –using the participants’ own words to explain what each of the central concepts were and what was revealed during the map building process. The transcripts therefore do not constitute the primary data; rather they are recorded to ensure that when the work is written up, the map is presented authentically rather than ‘revoiced’ by the person or people writing the analysis up. An independent reflection on the spatial arrangement of concepts on the map may be highlighted by a researcher as an additional aspect of its presentation, but we suggest that the facilitator should prompt participants to undertake this reflection on the spatial arrangement of ideas as part of their map presentation, rather than report their own thoughts and interpretations of that arrangement in a way that excludes the people who built the map from owning that aspect of the analysis tool.

Applications of CoNavigator

The various steps outlined above are put together depending on the purpose of the session. Whereas CoNavigator at first was mainly used in exploratory processes, as part of introducing a new topic in teaching or exploring areas of interest in a research group, the tool has in past years been used in more settings and varied ways. For example, CoNavigator has been employed in a Liberal Arts and Sciences bachelor programme (van Lambalgen & de Vos, 2023). By providing a structured moderation framework, the tool enabled multidisciplinary student groups to navigate the complex process of defining interdisciplinary research questions and synthesizing insights from different disciplinary perspectives. The research revealed that the CoNavigator sessions were particularly effective in helping students actively engage with different ways of knowing, create constructive dialogue, and develop epistemic fluency by providing a safe, structured environment for exploring and connecting diverse disciplinary approaches. The tool offered students a valuable space to acknowledge uncertainty, negotiate differences, and collaboratively construct a more comprehensive understanding of their research question.

As part of a participatory intervention project focused on improving cancer rehabilitation for elderly migrants (Pii & Bryld Shooghi, 2024), CoNavigator was employed in a stakeholder workshop designed to explore new forms of rehabilitative support for this underserved group. The workshop brought together a diverse set of participants, including NGO representatives, social workers, relatives of patients, municipal actors, professionals from the Migrant Health Clinic, and civil society stakeholders. The aim of the session was to identify potential interventions and areas of engagement that could support elderly migrants and their families throughout the cancer rehabilitation process. Using CoNavigator as a structuring and participatory tool, stakeholders collaboratively mapped out challenges, needs, and possible responses, with particular focus on cross-sector coordination, language barriers, and culturally appropriate communication strategies. Through a sprint-like process, participants built a shared understanding of the complexities surrounding cancer rehabilitation for migrant populations and co-identified key areas for intervention. These included improved access to translation services, better integration between hospital and community care, and support for informal caregivers. The session demonstrated CoNavigator’s capacity to structure inclusive stakeholder involvement and translate shared insights into concrete directions for service design. Outcomes from the workshop are now informing the design phase of the intervention study and serve as a foundation for further collaboration across sectors.

Following these positive experiences of extending the use of CoNavigator, Lindvig and Hillsersdal started employing the tool in ‘interviews, workshops and as part of participatory action research (see Lindvig et al., 2025), and Wood and Earle have been piloting the formalisation of it as a method of data generation and analysis in the context of research where academics, practitioners and community members work as a collective to interrogate contested topics. The use of CoNavigator for data analysis in the context of formal research rather than as a tool for discussion is a novel development. The first published account of this is found in Winder et al. (2025): here we used CoNavigator to explore diverse participants’ perspectives on the topic of ‘desistance’ in the context of the criminal justice system. The participants were forensic practitioners and research psychologists, a criminologist, a researcher with lived experience of sexual offending and others with lived experience of the criminal justice system. Winder et al. (2025) describe how the steps of a CoNavigation permit a form of collaborative data analysis (Cornish et al., 2014) and align with the activity flows outlined in Miles and Huberman (1994) of data reduction (e.g. Steps 1, 3, 7 and 8 described here), data display (Steps 2 and 9) and conclusion drawing / verification (Step 10). These experiences provide the following arguments for why CoNavigator can be used to increase diversity and inclusion in research, not just in the co-design of projects, but particularly in relation to participants’ analysis of their own data.

Addressing Dominant Voices

As illustrated in the examples given above, CoNavigator enables a safe space for diverse groups of participants. Collaborating groups can experience imbalances, and hierarchies can become embedded into narratives, discussions, and solutions. CoNavigator is designed to help mitigate some of the asymmetries in the intersections of collaboration: differences in levels of expertise and individuals’ perceived agency, how their specific background or experience is understood and perceived by other participants, and diversity-based issues. There is no hierarchy of tiles. Each tile is identical in size, and therefore identical in importance. Rather like the stops in a subway map, they matter in terms of how they are connected to each other. Equally, each participant elevates the tile of their choosing, regardless of its ‘popularity’ with the other team members. Flagging tiles for importance using the coloured pegs is done silently, with the focus on hands and hand-gestures reducing the chances of coercion from other members of the team.

Especially with group interviews, researchers such as Merton et al. (1990) and Kvale (2006) have pointed to the risk of dominance and unequal power relations among the participants, and therefore advocated for recruiting homogenous groups of participants for interviews. This has been a barrier to including diverse representation in group interviews and made it almost impossible to perform vertical interviews, i.e. group interviews that include participants at different hierarchical or institutional levels. The first time, Lindvig tried this was in a postdoctoral project where she explored the use of digital methods in teaching across Danish Vocational Education (c.f. Ellemose Lindvig et al., 2023). As part of the project, she visited schools across Denmark and interviewed management, teachers, digital consultants and developers. Because the aim was to gain insight into the reflections, reservations and discussions of including digital methods in teaching, individual interviews were not ideal and as the time was scarce, there was not enough time to gather people at each level of the schools for group interviews. The solution was therefore to conduct one interview per school and run it as a 3-hour CoNavigator session, where representatives from all levels of the school participated. Aside from the logistic benefits, the main outcome of the interviews was how CoNavigator enabled the informants to control the conversation and move forward with the discussions (move to action).

Removing ‘Researcher Control’ of the Conversation

A typical source of researcher bias in interviews is that the interviewer and the questions control the conversation too much, and consequently can confirm what the researcher expects to find. However, as CoNavigator sessions are not guided by questions, but by one prompt to kick off the session, there is limited opportunity for the facilitator to force the participants’ narrative accounts in a set direction. Instead, the various steps help the informants individually and collectively produce the topics and discussions that are the most important to them. CoNavigator sessions highlight not just what is important to the issue under discussion, but explore the different perspectives on why it is important to different actors – in this way consensus over a key element does not shut down further conversation about ‘what it is’, but expands on it to understand diversity of experience. By slowing down the pace of the discussion in this way it further reduces the bias from dominant voices who may be keen to move directly to determining a solution to suit a unidimensional interpretation of a problem. Rather than race towards reaching common ground, teams are encouraged to find their ‘uncommon ground’ – are there are central ideas and principles which they believe they share, that are not identically shared, or are understood differently? This helps to counter the situation where actors can be at an advanced stage of planning actions only to discover that central ideas or values are not in fact shared, so the success of those actions is compromised.

Participants Undertake the Analysis and Interpretation

The process of laying down tiles, moving them, grouping them, exploring them and then elevating key concepts collaboratively in the way described above results in a set of conceptual codes and core themes that are collectively determined in a way akin to other more established methods of qualitative analysis such as thematic analysis, grounded theory and narrative analysis (see Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). However, the difference is that the CoNavigation process enables participants to simultaneously explore, organise, interpret and analyse their own contributions rather than handing that process over to a researcher who will allow their knowledge and understanding of the topic, coloured by prior research, to influence the interpretation of participants’ narrative contributions to a discussion. In this way the tokenistic or performative inclusion of participants in data interpretation (e.g., where participants may be shown the results of an analysis that the researcher has arrived at and asked to comment upon its accuracy) is unnecessary. While co-production of knowledge with informants is a burgeoning field (see for instance Achiam et al., 2024; Ban et al., 2017; Vitting-Seerup et al., 2023), it has so far been a time-consuming process, with several rounds of meeting, analysing and interpreting together. With CoNavigator, these rounds are combined into one session as all voices are equally represented and heard.

Enabling Contributions from All Actors

In one group interview with temporary healthcare workers, the participants were diverse in terms of language skills. This meant that one of the participants needed more time to engage in the conversation. Because the CoNavigator process consists of individual steps where each participant writes topics on the tiles that do not leave the table, everyone’s contribution was included in the conversation. Crucially, the group was not able to race ahead without the contributions of this person, and they were afforded the time that they needed to gather their thoughts and represent them on the tiles at the outset of the process. Had this been a traditional focus group format, this person would have experienced marginalisation from the conversation which would have moved at the pace of (and in the direction of) the most articulate members, and their contributions would have been more difficult to introduce and value. As all tiles remain on the table throughout the process, their contributions are also not filtered out in the same way as can happen through conversational methods.

Limitations to the Method

A key practical limitation is that in order to begin using CoNavigator with any group, the user must either purchase or otherwise produce the physical elements of the tool, and be able to access some initial training on how to use the technique (see Box 1). Although this is true for many other forms of data collection or data analysis methods, we do recognise this is a potential barrier to the adoption of CoNavigator for some reseearchers, and as a result may contribute to inequalities in terms of access to it. Moreover, whilst the ability to undertake qualitative data collection and analysis in the space of a couple of hours represents a significant improvement in time required to undertake a project, for some contexts and users a two-hour session is unrealistic. For example, where we may wish to use CoNavigator with schoolchildren, it is typically not possible or practical to undertake all the phases in a single session. As a result, we are currently piloting a variation of the process which is split into several self-contained sessions which link sequentially into a full CoNavigation, and which minimises the amount of time that a child may be required to maintain their attention or be absent from a regular lesson.

Another limitation of CoNavigator as it stands is that it does require actors to be able to explain why they have contributed what they have – the tiles may represent the ideas pictorially for those who lack confidence in their writing abilities, or in the context of ideas that they are uncomfortable referring to by name (e.g. a reference to something traumatic), but all contributors need to have a means by which they can then discuss what they have put down. In the case of participants contributing to a session run in a non-native language, or participants with more limited communicative abilities because of disability or neurodivergence, they may need access to translation support or facilitated methods of communication. The fact that it is a process that is quite tactile and visual in nature renders it more accessible than some other methods of data collection, but the conversational elements, and the interpersonal aspect of it means that some actors may not find this process accessible as it stands. However, the steps of the process have the potential to be reconfigured and adapted to make it more inclusive, and thoughtful consideration of what each participant needs to enable them to contribute in the best way possible should be a feature of the preparation for any CoNavigation. In the case of autistic individuals, research has indicated that communication is optimised where communication occurs between individuals who are all autistic, when compared to situations where communication is led by non-autistic others (Crompton et al., 2020), and so in this case we would recommend that group composition is a key consideration to ensure information loss is minimized.

Another area of difficulty noted in feedback from Autistic adult participants is that the map can quickly become visually overwhelming where there have been a lot of contributions. The need to visually differentiate some parts of the map through the use of colour was flagged as a potential improvement. Coloured pens offers one solution, but would involve re-writing tiles. A simple solution has been arrived at through the use of coloured translucent overlays that can be placed on top of the tiles, enabling the writing to be read clearly through them. This has been found to be a good solution to this challenge and may also benefit other neurodivergent groups who experience visual stress. However, other aspects of the sensory environment would still need to be assessed and managed, especially as these will change on a person-to-person basis. As a result we recommend the use of a preliminary familiarisation phase, in which neurodivergent participants have the chance to experience the elements of the toolkits, gain a sense of what will be discussed and what is required in terms of interaction, and any adaptations or accommodations made accordingly. Even with this, there will still likely be groups of participants for whom CoNavigator is not recommended.

Conclusion

We have presented a framework for evaluating the quality of participant inclusion in the research process, with particular attention paid to both project design, data collection and data analysis. We have argued that there is a need to actively include community members not just in project design, but also in the analysis of data as part of inclusive research processes, rather than position them in ways that implies that their participation in this stage of this process may constitute a threat to rigour. One method that represents a viable alternative to traditional focus groups or interview-based methods is the use of CoNavigator, as it permits a more inclusive method for co-design, and gives hands control of the analytic process over to research participants. There is a need for more development of the approach to enable its use with those who may experience barriers to their participation in such sessions, but we see this as a structured and transparent method for research collaboration with community partners that has a phase of strategy creation for positive action built into its process.

.jpg)

.jpg)