Introduction

Participatory research (PR) is an approach that deviates from traditional research by prioritizing shared power, co-creation, and partner-led processes (Cargo & Mercer, 2008; Wallerstein et al., 2018). PR uses diverse participatory approaches that may involve stakeholders in the research in different ways based on their interests, availability, and expertise (Key et al., 2019). PR is a general term that encompasses Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) and Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR). CBPR is committed to partnerships that center equitable power-sharing and decision-making throughout the research process (Israel et al., 1998; Key et al., 2019; Wallerstein et al., 2018). CBPR principles prioritize community identity and assets, shared power through co-learning, the integration of ecological health determinants and actionable knowledge, and ensures iterative collaboration, inclusive dissemination, and sustainable outcomes (Wallerstein et al., 2018). CBPR is commonly used with adults in the health fields to guide health interventions and policy change. YPAR positions young people as experts and co-researchers in investigating issues affecting their communities. A study is YPAR if it centers youth experiences, involves youth as equal research partners, and aims for positive social change (Caraballo et al., 2017). YPAR studies have been primarily implemented with adolescents and older youth (Anyon et al., 2018; Shamrova & Cummings, 2017). In this paper we primarily use PR to represent CBPR and YPAR.

Although scholars have increasingly utilized participatory methods and tools to listen to young children and gain insight into their worlds (Montreuil et al., 2021; Sevón et al., 2023), many of these studies have mainly involved children in data collection processes and do not meet the principles of shared power, equal partnership, and actionable change. Despite the growing adoption of PR methods, preschoolers are rarely included in PR studies that meaningfully redistribute authority, sustain equitable partnerships, or translate insights into social change. (Anyon et al., 2018; Jacquez et al., 2013; Shamrova & Cummings, 2017). Including very young children in PR is crucial because it fosters youth learning, community improvement, and builds children’s capacity to address issues that matter to them.

Several reasons contribute to this exclusion. Preschoolers’ limited verbal and literacy skills preclude traditional data collection methods like surveys and interviews (Jacquez et al., 2013; Montreuil et al., 2021). Gatekeepers responsible for protecting children, such as administrators and teachers, have concerns about the appropriateness and feasibility of involving young children in research (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2014; Montreuil et al., 2021). Challenges in obtaining parental consent can also be significant, as parents may have reservations about their young children participating in research activities (Shamrova & Cummings, 2017; Water, 2024). Additionally, there are ethical considerations regarding the ability of preschoolers to understand and assent to their involvement in research (Dockett et al., 2012; Water, 2024). As a result, preschoolers’ perspectives are often missing and research heavily relies on data from adult proxies typically teachers and parents (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2014). This study is a departure from many CBPR, YPAR, and early childhood research studies by offering methodological guidance gained from detailing the process of conducting participatory research in a preschool classroom.

Participatory Research

Participatory research (PR) has a rich history dating back to the 1970s and aims to involve participants in every phase of the research process such that participants control the direction and focus of the study (Hall, 1981; Tandon, 1988). Participatory approaches center on “inclusivity and of recognizing the value of engaging in the research process (rather than including only as subjects of the research) those who are intended to be the beneficiaries, users, and stakeholders of the research” (Cargo & Mercer, 2008, p. 326). PR is concerned with examining how power is shared throughout the research process (Israel et al., 1998; Key et al., 2019; Wallerstein et al., 2018) which contrasts with traditional research approaches that view participants as subjects to conduct research on (Wallerstein et al., 2018).

The breadth of terms describing PR approaches across disciplines has led to the emergence of a range of models that overview varying levels of participation, some of which are presented on a continuum (Arnstein, 1969; Cornwall & Jewkes, 1995; Key et al., 2019; Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020). These models provide a structured way to understand the extent of involvement in the research process. For instance, Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of citizen participation metaphor illustrates how participation can vary from minimal involvement, such as being informed or consulted, to more active and empowered roles, such as collaborating or leading initiatives. These varying levels of participation serve different purposes and can be adapted based on the readiness, needs, and anticipated benefits of all community members involved, including researchers, community members, and funding bodies.

Key et al. (2019) place CBPR at the highest level of participation and power balance on the Community-engaged research continuum. Nine principles characterize CBPR (see Wallerstein et al., 2018) and the approach respects the autonomy, expertise, and strengths that community members bring to the research process (Brydon-Miller, 2008). Broadly, PR models of participation highlight that adaptability is crucial as the level of participation may evolve over the lifecycle of a project. When including preschoolers in participatory research, it is essential to study their readiness and needs to ensure meaningful participation since their ability to engage in the research process may differ significantly from older participants. CBPR principles and the transformative PR process marked by reflexivity, iteration, and flexibility (Buchanan et al., 2007; Cornwall & Jewkes, 1995) makes CBPR effective for engaging and empowering early childhood populations that are often overlooked or excluded from research.

Participatory Research with Young Children

To effectively implement PR with young children, researchers have developed methodologies tailored to young children’s unique needs and capabilities. One such innovative methodology that is often used in early childhood research is the Mosaic approach. The Mosaic approach is a multi-method framework for capturing young children’s perspectives and experiences (Clark & Moss, 2011). Studies have applied the Mosaic approach as a way to listen and engage with young children’s perspectives regarding a variety of topics including their early childhood education and care environment (Katsiada & Roufidou, 2020), to inform program evaluation (Martin & Buckley, 2018), and pedagogical tools in early childhood settings (Polyzou et al., 2022; Rouvali & Riga, 2018).

Scholars have also engaged young children in visual and playful methods to learn their perspectives on early childhood education teaching (e.g., drawings, Rodríguez-Carrillo et al., 2020), their well-being when transitioning to school (e.g., emojis, Fane et al., 2018), or their understanding of the outdoor environment (e.g., role-playing, building models, Green, 2017). Blaisdell et al. (2019) underline the usefulness of creative and open-ended approaches that are flexible to young children’s preferences and developmental stage. Language-based methods often employ interviews or use multiple tools to help in the interpretation of young children’s experiences such as through games and photography (Adderley et al., 2015; Merewether, 2015). For instance, storytelling and focus group adaptations using toys have been used to understand young children’s attitudes towards books and reading (Jug & Vilar, 2015). Moreover, informal conversations with young children have been used in the co-creation of ethnographic field notes (Albon & Barley, 2021). Taken together, scholars have used a range of methods to engage young children in the research process, recognizing their competence in sharing their own perspectives and experiences.

Youth Participatory Action Research

Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) is a form of participatory research. It specifically elicits youth participation in the research process not as participants but as co-researchers. It is considered an orientation of CBPR, focusing on youth engagement and empowerment (Hart, 1992; Ozer et al., 2020). In YPAR, youth are viewed as the “experts in their own lives” (Jacquez et al., 2013, p. 183) and are recognized as having the same rights as any other person (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2014). For a study to be considered YPAR, three principles must be met: (1) the study should be grounded in the lived experience of youth; (2) youth should be collaborative partners in all aspects of the research; and (3) the study should be transformative such that there is potential for positive social change (Caraballo et al., 2017).

According to Treseder’s (1997) Model of Participation, there are five different types of participation with youth (Stuart et al., 2015; Treseder, 1997). In Treseder’s model, the varying types of participation are depicted situationally and equally, which differs from the hierarchy of Hart’s (1992) ladder of participation (Stuart et al., 2015). Treseder’s model depicts the following five types of participation in working with youth: (1) assigned but informed; (2) adult-initiated, shared decisions with young children; (3) child-initiated and directed; (4) child-initiated, shared decisions with adults; and (5) children consulted and informed (Barber, 2009, p. 27; Stuart et al., 2015; Treseder, 1997). It is important to note that within this study, the researchers reserve the word choice for “youth” to refer to the YPAR approach and studies with adolescent-aged children, whereas “children” is used as a general description for minors with a particular emphasis on early childhood and elementary school-aged children. While youths’ developmental age may influence how a study is conducted and the level of youth participation, YPAR applies across all ages with age-appropriate activities. Yet, most participatory studies with youth do not include children younger than ten years old due to misconceptions about their developmental ability to participate or a lack of developmentally appropriate research tools to engage younger age populations (Shamrova & Cummings, 2017).

Benefits of YPAR in Early Childhood Settings

There are many benefits of conducting YPAR for the field in terms of methodological innovations and for all actively engaged partners and other beneficiaries of the research in terms of their development and contributions being recognized. Methodologically, PR contributes to the ongoing development and refinement of methods that are appropriate, respectful, and effective in studying young children’s perspectives and experiences. For instance, scholars have incorporated innovative approaches to obtaining consent which include using simplified comics with basic symbols and stick figures in storyboard formats (Tatham-Fashanu, 2022), as well as employing storytelling methods and age-appropriate visual consent forms (Manassakis, 2020). These are just some examples of creative techniques designed to enhance understanding, engagement, and accessibility for young children, ensuring their active participation and comprehension throughout the research process.

YPAR has many benefits in empowering youth to share their perspectives and opinions. YPAR with young children encourages the inclusion of children’s perspectives that diverge from conventional adult viewpoints, promoting dialogue and integration of these perspectives into research outcomes (Gray & Winter, 2011; Lundy et al., 2011). YPAR can highlight youth’s unique perspectives to stakeholders who may not typically consider young people’s insights. When youth contributions are recognized and valued, it can lead to increased confidence and self-efficacy among young participants. This recognition, combined with the skills and knowledge gained through the YPAR process, can empower youth to actively engage in addressing community issues (e.g., schools, local government) effectively becoming agents of change (Jacquez et al., 2013). Adults can gain insights into children’s peer culture, enhancing their understanding of children’s experiences and interactions (e.g., Spiderman shooting-a-web; Tatham-Fashanu, 2022).

YPAR creates opportunities for youth to enhance their socioemotional and cognitive development and to acquire new skills to become agents of change in their communities (Shamrova & Cummings, 2017). Moreover, by having youth participate in YPAR projects, the child’s community culture may be more likely to recognize and include children’s participation moving forward and show increased awareness such that new initiatives consider children’s needs as well (Shamrova & Cummings, 2017). While scarce, there are a few studies that demonstrate how young children, given the opportunity, can be empowered to make changes in their environment by sharing their perspectives. To illustrate, a study exploring preschoolers’ perceptions of school bathrooms used various methods to collect data such as stories, drawings, and conversations to understand why some of the preschoolers perceived school bathrooms to be unsafe (Millei & Gallagher, 2011). Researchers found that the preschoolers were willing to share their views on bathroom privacy, bathroom safety, and even provided solutions on how to mitigate bathroom-related issues. By empowering the preschooler’s voices and incorporating their feedback into the bathroom redesign plans, the researchers both collaborated with and gave agency to this group of young children.

Another study among Swedish four-year old’s explored how children navigated the health care system by capturing video observations of their verbal and bodily expressions during a healthcare visit that were later analyzed (Harder et al., 2013). Researchers were intentional about not only obtaining consent via parental proxy, but also by creating research brochures specifically for the children to be informed of the study before asking the child for their own consent, which is in line with the second principle of youth participatory action research. Findings suggested that children utilized different negotiation strategies throughout their health care visit to reach an agreement or to delay progress in their respective situations. These studies demonstrate that conducting participatory research studies among the youngest of children is feasible when the approaches are developmentally appropriate and situated around children’s perspectives. This study also demonstrates that whether adults realize it or not, children influence any situation they participate in in overt and subtle ways, which supports the case that youth participatory action research can be useful in child-related matters.

Building on this foundation, child-led research has emerged as a powerful tool for understanding children’s experiences and perspectives. Child-led research involves children actively leading research projects with adults as facilitators (Mateos-Blanco et al., 2022). Tisdall et al. (2023), highlight how this approach enables children to develop their own research methods and analytical techniques, thereby enhancing their cognitive and investigative capabilities. In their study, this process entailed children engaging in collaborative discussions to determine research topics, utilizing creative techniques such as mind mapping and list-making to organize their thoughts and ideas. Throughout the research process, adult facilitators played a crucial supportive role, employing narrative observations to document significant moments and children’s reflections, ensuring that the young researchers’ voices and perspectives remain at the forefront. This collaborative approach led to rich, multi-faceted explorations of the chosen topic, with children sharing knowledge among themselves, conducting field research, interviewing adults, and capturing visual data through drawings and photography (Tisdall et al., 2023). The culmination of these efforts resulted in the creation of a comprehensive research book, which not only served as a tangible record of the children’s work but also as a testament to their growing capabilities as researchers. The literature increasingly supports this approach, with studies demonstrating that child-led research fosters independence, emphasizing children’s agency, intelligence, and capacity for learning (Mateos-Blanco et al., 2022).

Challenges of YPAR in Early Childhood Settings

A major limitation for the field is the dearth of YPAR studies among children under age ten (Shamrova & Cummings, 2017) and even fewer studies involve children under age six (Anyon et al., 2018; Jacquez et al., 2013). While this is likely due to beliefs about children’s abilities to contribute to participatory research and the lack of developmentally appropriate research tools to engage younger children in different aspects of the research, more efforts should be made to include children of all ages in participatory research (Jacquez et al., 2013; Shamrova & Cummings, 2017). For preschoolers in particular, their lack of representation may be inspired by Piagetian beliefs about young children lacking critical thinking skills (Shamrova & Cummings, 2017) and adults resisting power sharing with younger children (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2014). This is especially important considering studies have been done to young children not in partnership with young children.

Engaging preschoolers in participatory research also presents several developmental challenges for commonly used research methods like surveys and interviews. Scholars admit that it can be challenging working with young children when their literacy, numeracy, and ability to think beyond their own experience are still developing (Lundy et al., 2011). Additionally, the effectiveness of young children’s involvement in research can be influenced by individual differences in children’s abilities, attention spans, and communication skills (Gray & Winter, 2011). Thus, issues can arise in consistency and reliable interpretation of responses. This may be exacerbated when children face language barriers within the classroom (Tatham-Fashanu, 2022).

Researchers need to be mindful that the methods used in the research process can include or exclude different forms of child communication, thus influencing which children may appear more “competent” for research (Tisdall et al., 2023). For instance, the use of comics are appealing but very time consuming and still required that young children provide verbal feedback on their drawings (Tatham-Fashanu, 2022). Thus, scholars caution against the dominance of words, highlighting the need to fully consider a range of nonverbal and visual forms of communication and expression (Tisdall et al., 2023). One way scholars can address these challenges is through the Mosaic approach; by combining multiple “tiles” of information, such as interviews, tours led by children, and children’s drawings, researchers can create a more comprehensive picture of children’s worlds (Martin & Buckley, 2018; Rouvali & Riga, 2018). By addressing these challenges, researchers can create inclusive and effective participatory research environments that truly benefit preschoolers and their communities.

Current Study

This study aimed to empower preschool children (ages three to five) and their respective teacher to realize their assets and engage in a project that could affect real change to their immediate classroom and school context. To maintain clarity and consistency throughout the rest of this paper, we have chosen to use the term PR as an overarching concept. This decision allows us to encompass the broader principles and practices of collaborative participatory research methodologies (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020). However, it is important to note that CBPR and YPAR principles were instrumental in guiding our decision-making processes at critical junctures in the research process. PR approaches provided an opportunity to engage teachers and children at the preschool. In contrast to more traditional research methods, a PR approach allowed us to disrupt the power hierarchy embedded in this lab school by engaging preschoolers and teachers as co-researchers with academic partners. Our approach went further by intentionally including preschoolers in our project to understand, listen, and engage with their perspectives as the researchers collected data. The researchers used the Photovoice method in a participatory way that enabled participants to identify, represent, and enhance their community through photography (C. C. Wang, 1999). In our study, the preschool teacher was active in co-learning and co-developing this study. The children reached the assigned but informed type of participation (Treseder, 1997) given that the children were not developmentally ready to take ownership of the research process. Children were informed about the purpose of the project, the researchers obtained their assent and incorporated their perspectives as the central focus of the Photovoice component. This article focuses on the process of implementing a participatory approach through the use of a photo-elicitation method rather than on outcomes. As such, the paper primarily captures the adult researchers’ experiences and observations implementing the project. As researchers, we hoped to learn from the teacher’s and preschoolers’ perspectives to refine current knowledge about their experiences.

Methods

Context

This study was initiated as part of a graduate course on participatory research methods. The course overviewed principles and distinct types of participatory research methods. After initial instructor-facilitated preschool agreement to serve as a research site for this course, students independently managed the participatory research project, with instructor scaffolding and support as needed.

Setting

This study was conducted at a university-affiliated child development laboratory (CDL) with a focus on supporting teaching, research, and service activities. It uniquely allows direct observations of a diverse pool of children across four classrooms and utilizes child-centered, research-based and evidenced-based approaches to learning that are developmentally appropriate for preschoolers. Student researchers developed a partnership with a preschool classroom lead teacher and her classroom children (herein referred to as “preschoolers”).

Participants

Participants included 16 preschoolers, a lead teacher, and an administrator (laboratory director). The lead teacher (15 years of teaching experience) expressed interest in having her classroom (N=19 preschoolers; 3-5 years old) participate in the study. A total of 16 preschoolers actively participated and constitute the analytic sample (Mage = 4.0; SD = 0.71; 47% girls; 53% boys, 35% Biracial, 29% White, 24% Asian, 6% Black, and 6% Other). Demographic information was obtained from the administration through parents’ self-reported records. While the researchers already had administrative and parental approval, they still asked each child to assent to their participation in the Photovoice project. The children actively participated by engaging with the researchers during a predetermined time slot to take photographs, identify their favorite photograph, and discuss what they liked most about the area they photographed. The director and lead teacher were interviewed after study implementation.

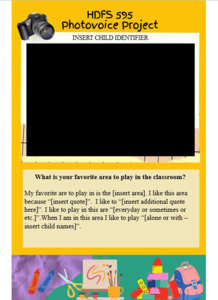

Procedures

During Summer 2021, the course instructor reached out to the CDL director to determine whether there was interest in engaging in a participatory research course project. One lead teacher expressed interest in participating and met with the instructor to discuss expectations. Study procedures were reviewed by the Institutional Review Board and determined to be non-human subjects research given that the project focused on the process of implementing participatory research in the preschool setting rather than on children’s outcomes. In accordance with PR principles, the researchers included the main preschool teacher at each stage of the research project (see Figure 1 for research stages and timeline). The researchers contacted the lead teacher to discuss and plan the project, beginning with an initial introductory meeting. The lead teacher provided information on the classroom, ongoing and upcoming activities including student teaching, and guidance on how to best engage with preschoolers. Plans were made to build rapport with preschoolers in the classroom before implementation. Student researchers coordinated implementation scheduling, project paperwork, contact information, and immunization records with CDL staff.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers adhered to CDL policies aimed at protecting preschoolers who were not able to be vaccinated due to their age and mitigating spread among teachers, staff, and parents (weekly COVID testing regardless of vaccination status; masking and temperature taking in classrooms and laboratory school; signing in and out). Once cleared to implement, the researchers visited the classroom for an hour twice weekly with the first two weeks dedicated to building rapport with the preschoolers and later weeks focused on data collection. Meetings after the initial meeting with the lead teacher centered around discussions about possible research questions, project design, implementation, and dissemination. The researchers and teacher chose to incorporate an arts-based approach that would empower and engage preschool aged children (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2014; Jacquez et al., 2013).

Arts-Based Data Collection Approach

The researchers and lead teacher aimed to engage preschoolers through an arts-based approach that would complement the child-led and play-based curriculum of the CDL (Q. Wang et al., 2017). This approach would engage the children in research through a medium that was accessible, familiar, and developmentally appropriate. Further, it allows children to communicate their lived experiences on their own terms. The researchers considered asset mapping, Photovoice, and the Mosaic approach and settled on Photovoice because it was relatively easy to implement and it would be an interactive way to achieve greater engagement from preschoolers.

Photovoice

We use an adaptation of Photovoice as a PR strategy as it enables the use of photography as a tool to document and shed light on important issues in people’s lives (C. C. Wang, 1999). Photovoice has three main goals: it should “enable people (1) to record and reflect their personal and community strengths and concerns, (2) promote critical dialogue and knowledge about personal and community issues through group discussions of photographs, and (3) reach policymakers” (C. C. Wang, 1999, p. 185). This approach can promote aspects of PR such as action and equitable participation (Ford & Campbell, 2018; C. C. Wang, 1999). Photovoice is useful because it is interactive and relatively easy to use, it promotes reflective thinking, and it can be used to capture evidence that can lead to action (Ford & Campbell, 2018). Additionally, Photovoice as an approach that values community stories and knowledge (C. C. Wang, 1999).

The lead teacher shared that some of the children may enjoy the opportunity to engage with technology and she had been wanting to incorporate this into the classroom for a while. She thought Photovoice would allow the preschoolers to use cameras, something many had not previously experienced. The researchers consulted with the lead teacher and decided to explore the preschooler’s favorite areas of the classroom to better inform the activities she would use in the classroom. The researchers initially meant to use iPads, but those items were already reserved for another activity, and were unable to obtain disposable cameras. The researchers reserved two Nikon D5200 cameras from the university library and created a Photovoice protocol that provided basic information about the approach and specific steps to train the preschoolers. With the lead teacher, a data collection timeline and data collection plan were created to be compatible with the classroom daily routines. The lead teacher created a list that separated students into groups across three days.

Data collection days consisted of the two researchers taking turns either training preschoolers on how to use the camera or taking notes and audio recording each session for each preschooler’s comments on the activity. Data collection spanned four sessions (not 3 as planned). Children were called into the classroom in pairs. The teacher had all classroom activity areas available. The lead teacher kept track of each child and would bring preschoolers into the classroom when it was their turn. During the camera training the researchers gave a brief description of the purpose of the project and obtained child assent for participation and audio recording by directly asking them a yes/no question of whether or not they: a) wanted to participate by taking photos of their favorite areas of the classroom and answer questions about the area and b) were okay with being recorded. Each child was taught how to hold the camera and was shown how to take pictures.

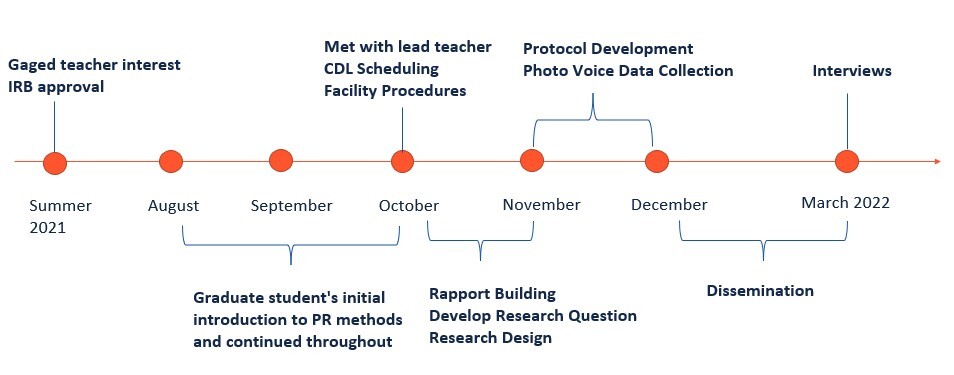

After the practice session, each child had approximately 15 minutes to take photos freely across any activity area of the classroom they deemed was their favorite to play in and the researchers ensured each child took at least five photos during that time. Immediately following the photography session, a researcher and the child would review the images together on the camera’s display, and as they looked at each photograph, the researcher would ask open-ended questions like, “Which of these pictures do you like best?” to gauge the child’s preference (see Figure 2). The children were then asked to discuss their favorite areas in the classroom. The researchers adapted questions from the SHOWeD method to help the preschoolers describe their photographs (C. C. Wang, 1999). Based on the lead teacher’s feedback, the researchers adapted the questions to ask: What do you usually do here? Why do you like this area? Is there something special about this area? What is it?

Their narratives, which were responses to the aforementioned SHOWeD method, were audio recorded before, during, and after taking photos. The lead teacher and researchers often asked probing questions to encourage preschoolers to provide more detailed information. All audio recordings were transcribed verbatim by the researchers to include their reasoning as to why the picture area in their template was their favorite area. The researchers and lead teacher planned to dedicate a circle time or free play time for students to share their thoughts about their pictures with their peers. The idea was to have a show-and-tell activity where each child’s chosen picture could be displayed on a rolling screen to have children take turns discussing them. The researchers were interested to see if preschoolers reinterpret their pictures when sharing with the group.

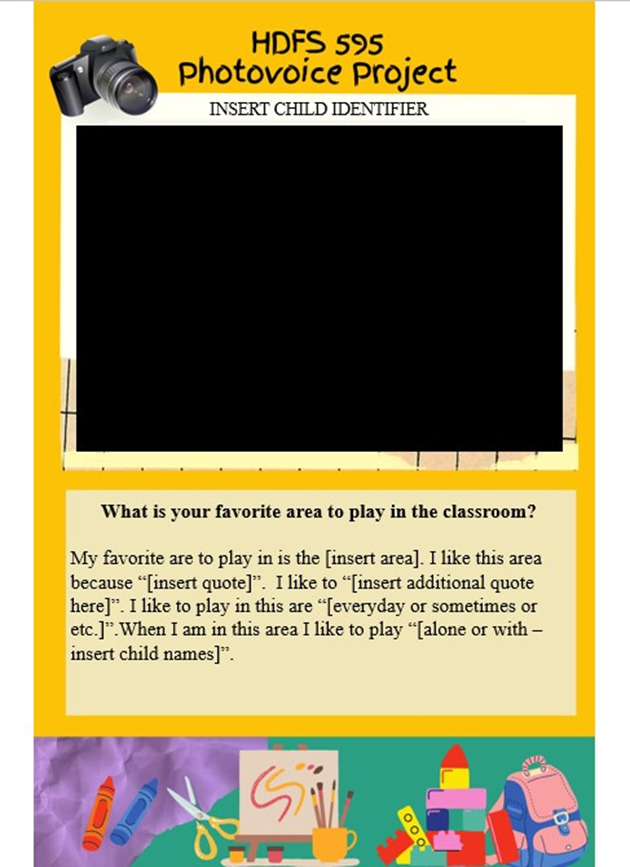

Data Sources

Throughout the research process, the researchers recorded detailed weekly meeting notes that included agendas and meeting minutes. Researchers and the lead teacher took notes separately and shared those notes as needed with one another after site visits and scheduled meetings. All meeting notes, shared materials, and email exchanges were included in the analysis. They also developed and referenced a standardized Photovoice template to conserve, display and share each child’s chosen photograph and comments about their favorite play area (see Figure 3). The use of multiple data sources ensured findings were grounded in data.

The researchers engaged in reflective journaling activities as part of the course and often had debriefing conversations to document and compare their experiences. Discussions reflected on what went well, what was confusing and how it could be improved, and determining next steps. After the project was completed, the researchers conducted interviews with the lead teacher and CDL director to capture their final reflections about their experience with the project. The lead teacher answered questions like “What was it like for you as you were working on the CBPR/YPAR project?” For the CDL director, questions included “What were your initial thoughts, opinions, or concerns about conducting this CBPR/YPAR study at CDL with the preschoolers?”

Analytic Strategy

Reflective Journaling

Within the field of education, reflection allows for individuals to enhance their understanding and learning based on their respective experiences (Jasper, 2005). Within qualitative research, reflexivity is common and allows researchers to render a transparent, paper trail of the constructed research outcomes (Ortlipp, 2008). According to Jasper (2005), reflective writing can be viewed “as a method in itself, as a data source and within the analytical processes, can be used as a technique” (p. 249). Following reflective writing frameworks, reflexive journal writing should be written subjectively in the first-person with critical thinking embedded in discussions of how areas of concern were managed and the degree to which the researchers’ perspectives changed due to their learned experiences (Jasper, 2005). Meyer and Willis (2019) note how reflexive journaling can be helpful to novice researchers who might not have the insight to address challenges as they come up in the field but can retrospectively “develop strategic and carefully considered ways to address challenges” (p. 579) and help them further consider their positionality.

For this study, reflective writing is utilized as a data source and analytical technique. The results are analyzed via the amalgam of six reflexive fieldnotes ranging from the researchers first observational visit to their last data collection visit, the additional online Zoom meetings they conducted with the lead teacher, and the two individual interviews with both the lead teacher and CDL director after the study concluded.

Thematic Analysis

The researchers analyzed interview data via thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is prominently used among qualitative studies as it allows for the identification of patterns from the data and provides additional context that cannot be reached with quantitative data (Castleberry & Nolen, 2018). They relied on emergent thematic coding to find common themes between the lead teacher and director interviews. The researchers considered each respective interview to be a sampling unit and compared the interviews with one another to notice converging and diverging themes.

Results

Level of Teacher Engagement

For this study, the lead teacher was the primary community partner. In line with a PR approach, the researchers sought to achieve full and equitable participation of the lead teacher in the research process. They made a continued effort to include the teacher from the very beginning by asking questions about preference for involvement at each stage of the research process. The lead teacher played a key role in allowing access to the classroom and preschoolers. Given the short period of time the researchers had for the project, it was important to build rapport and effectively communicate with the teacher (see Figure 1 for timeline).

Although she was enthusiastic about the project, the lead teacher expressed concerns regarding staffing shortages and time constraints. In response to the teacher’s availability, the researchers accommodated their meeting schedule by communicating via email and through brief check-ins during their weekly classroom visits rather than their intended 15 - 30 minute Zoom calls. Email became a key communication mode with the lead teacher to accommodate everyone’s different schedules. Typically, the researchers met to create a meeting agenda that was shared with the lead teacher a week in advance to also consider her input. At times the agenda included detailed ideas or questions for the teacher to be discussed during the meeting.

During one of their meetings, the researchers expressed their interest in working towards a paper for publication and asked if she would like to be an author on the paper. She declined their offer because she was not interested in publishing. The lead teacher saw co-authorship as an expectation to take on responsibilities (writing) above and beyond her typical workload, which already included participating in research studies as part of the school’s core mission of generating new knowledge for the benefit of the public and its current students and teachers. The research team respected her preference and time

In the process of creating research questions, the researchers aimed to center the lead teacher’s interests and ideas. She mentioned that she preferred that the researchers come up with a couple of research questions for her to provide feedback on. In terms of data collection, she became very active in helping to ensure the children were comfortable and in probing for more information about their favorite areas of the classroom. When children would not answer the researchers’ questions, she would restate or reword the question so children were more likely to answer it. Further, the lead teacher provided feedback on more developmentally appropriate ways to ask the preschoolers about their pictures and also pointed out how the camera was too big for some of the children. The lead teacher taught the researchers that questions and instructions should be simple and demonstrated this by probing and repeating questions using concrete, non-abstract language.

Overall, the researchers believe that the lead teacher was able to reach a level of engagement that matches that of “community participation,” which refers to having some active role in the research (Key et al., 2019). In this way, the teacher provided feedback throughout the research process and was still able to engage as much or as little as she wanted in each phase.

Level of Preschooler Engagement

Developmental Appropriateness

For this study, the lead teacher advised that preschoolers are too young to cognitively engage in these stages of the research process. Therefore, the researchers co-developed a research question with the lead teacher that captured preschoolers’ interests and was developmentally appropriate. When working with the preschoolers, the researchers observed differences in preschoolers’ ability to (1) share their perspectives and (2) physically grasp and manipulate the cameras, requiring more hands-on assistance. Thus, at times, the researchers helped children stabilize or hold the camera as they pointed the camera and pressed the shutter button to take their photograph. With varying levels of assistance, all 16 preschoolers captured their focal target of choice via photos and voiced their thoughts. This demonstrated that Photovoice was developmentally accessible to preschoolers. Overall, the researchers believe the preschoolers reached a level of engagement that matched the assigned but informed type of participation (Treseder, 1997).

Rapport Building

The study timeline was limited to 16 weeks, as part of the fall academic semester. The researchers began working directly with preschoolers in the classroom in the eleventh week of the semester. They spent two weeks establishing and building rapport with the preschoolers before data collection began. In their first visit, they were introduced to the children very briefly. In subsequent visits, the researchers were intentional about letting the children lead, occasionally starting conversations with questions to build rapport. The researchers later joined their outdoor games when invited and did parallel activities indoors to build rapport, adjusting their approach based on their responses through careful observation and listening.

This study was conducted during an on-going global pandemic. Due to this, many steps were taken to ensure the safety of the preschool community and researchers, which included wearing masks at all times. Although these precautions were necessary and crucial for protecting the health of all involved, it is possible that masks limited building rapport because preschoolers could not see the researchers faces or expressions which is an important mode of nonverbal communication. They had to rely on the researchers verbal communication and nonverbal body language. They could not see the researchers smile and at times had difficulty hearing them clearly with the masks. While they were still able to socially engage and communicate effectively with preschoolers to functionally meet study purposes, it is plausible that some children may have been more comfortable had they seen each researcher’s face and facial expressions.

Children’s Participation in Photovoice

On the first day of data collection, some children playing outside were observed staring into the classroom as their peers took photos. In her interview, the lead teacher also shared that the children’s initial perception of getting to use cameras was well-received with excitement and were constantly asking when it would be their turn to participate. Preschoolers were reassured they would have the same opportunity on other days. Some children were more reticent to share their thoughts than others. Preschoolers’ temperaments and personalities were also considered as some preschoolers were more vocal and comfortable with the researchers relative to their less vocal peers.

All participating children took photos of their chosen area(s) and voiced insights about their choices. The children expressed joy by giggling, smiling, and wanting to keep taking pictures. Each child was asked to take a minimum of 3 pictures and attempted to limit each child to a total of five pictures as the researchers only had roughly 10 minutes with each child. The researchers checked for blurriness and deleted pictures that were too blurry. In the end, the researchers asked the children to pick their favorite photo and used respective comments for that area in the final Photovoice product. Due to unanticipated time constraints, we were unable to implement the planned show-and-tell photo sharing activity.

Accepting When Partners Want a Limited Role

The lead teacher acknowledged that she personally wanted the researchers to lead. She did not want to be “the main player” or “as big of a stakeholder.” She did state that she felt a responsibility to figure out “a way to make that bridge . . . so that the children got to know [the researchers] and felt comfortable.” She appreciated the regular communication, especially when plans changed with how the Photovoice data collection would look, and having knowledgeable researchers who know what they were doing to help guide the process. After the preschoolers participation, many of the children were happy to share their experiences with their caregivers, which resulted in the parents inquiring more about the project to fill in the gaps that the children were not as privy to. Overall, she had a positive experience and would like to see it implemented again and see it expanded by having preschoolers take pictures with a different focus in mind.

Capacity Building

Capacity building is central to PR approaches. The researchers provided several opportunities to support the teacher’s and preschoolers’ acquisition of skills and knowledge. In working with the teacher, the researchers devoted time to distilling information about PR with minimal jargon and easily accessible during their meetings and before leaving in-person classroom visits. For example, researchers curated several slides that detailed basic information about PR (e.g., definitions, benefits, challenges), strategies for coming up with research questions, and the continuum of community engagement (Key et al., 2019). Further, a Photovoice protocol was created that was specific to the preschool classroom environment. These materials were discussed in meetings with the teacher and shared with her for future reference. Focusing on one classroom ensured sufficient time to pilot the project and build the lead teacher’s capacity in participatory research processes and Photovoice methodology so she could train other lead teachers to conduct similar projects in their classrooms, promoting sustainability and scalability within the larger school context.

Empowering Young People

Empowering young people and giving them opportunities to have a voice in their learning fosters independence, ownership, and engagement. Thus, allowing them to contribute actively to their educational environment and personal growth, and instilling confidence and a sense of responsibility for their own learning journey. The lead teacher provided the following feedback at the end of the project:

I think it is important that teachers give the children in their classrooms a voice as to what they want to learn about and allow them to construct their own knowledge. This project gave the children an opportunity to voice and document their favorites classroom areas and materials. . .

In her interview, the lead teacher added how she was motivated to be a part of this project because she wanted the children to have the opportunity to “take kind of ownership of [the] classroom space and kind of using their independence and being able to come…kind of put their own spin on things.” She added that having the children use cameras was also a motivating factor as she was intrigued about how the project would turn out and how she could possibly do something similar in the future.

Embracing Participatory Methodological Approaches

The CDL director was initially interested to allow this project to take place at CDL because of his intrinsic interest in “looking at new and creative ways to support teaching and research and outreach and engagement activities.” He noticed that “this was the first time somebody had come to me with a topic or an idea that was initiative and very different in terms of taking a ground up approach to looking at identifying research questions” and “a growth opportunity” for students learning how to facilitate and become “engaged in these processes.” The director added that when he occasionally would observe from the observation booths above the classroom, he perceived the children to be engaged, which indicated to him that “they responded very well to the process [we] were walking them through.” The CDL director did add that:

We so many times, underestimate our children, even the younger children, and this approach is good, gives [us] a more realistic perspective of what they’re doing and what they see as important/not important.

Regarding the use of PR particularly in the early childhood setting, he added:

[I] would like to push the envelope . . . I think it’s a good methodological tool for different researchers looking at identifying curricular issues that need to be addressed from the ground up rather than top down first . . . I know we can do it now.

In regard to advice for building rapport, the CDL director stated that he used to think a minimum amount of hours was needed and required but has since changed his view. His view now is that “the onus” should be “on the researcher to decide how much rapport building is critical to gather the data” as different projects have different needs.

Both the teacher and director recommended that perhaps adjusting the logistical components of the project could have better outcomes. For example, it would have been better to obtain smaller, point-and-click cameras that are better suited for children’s physical development so they can grasp and capture photos with ease. Also, due to time feasibility the researchers were only able to work with one classroom, but both the teacher and director are open to seeing this type of research expanded, especially with the younger children.

Dissemination

In collaborative research projects, dissemination is critical in ensuring that the participants have access to the final research product and that the language to describe the results is understandable to the general public. In discussing the best approach with the lead teacher, the researchers considered creating a digital “e-brochure”, a bulletin board in the hallway, a bulletin board in the classroom, and a giant poster as they wanted both the children and their parents to see the results. First, with the teacher’s input, the researchers decided to approach dissemination in multiple phases and numerous formats to ensure that they shared the results with both the preschoolers and the preschool community (namely the teacher, preschoolers’ parents, and school director). Multiple phases were needed as each respective group engaged with different areas and materials at the school differently. For example, parents and children often both looked at bulletin displays, but children were seldom in the hallway and mostly in the classroom during the day whereas parents spent more time in the hallway than the classroom during school drop-off/pick-up. Additionally, the CDL community at-large may only frequent certain areas of the school based on their needs so a digital newsletter would make the findings accessible to everyone, even if they were not directly around the physical preschool classroom. Second, the researchers decided to create individual posters of the children’s photograph and summary that would be displayed in the classroom for the preschoolers. They created a custom template providing space for the child’s name, chosen picture, and a summary of their perspectives with shortened quotes (Figure 3). Third, for the parents, they opted to create a digital brochure that the teacher would send via email. This template was used for all audiences but in different formats: digital display in the classroom and e-brochure for distribution. For the CDL community, the researchers created a digital brochure that included a cover page briefly summarizing the study purpose and results. Following the cover page, each child’s photo and perspective was presented on a separate page (see Figure 4). The lead teacher already communicated with parents about the project and had suggested the development of the dissemination to be shareable via email. The lead teacher emailed the brochure to preschoolers’ parents and guardians as part of a monthly classroom electronic newsletter.

The researchers obtained permission from the CDL director and lead teacher to donate a digital photo frame to the classroom. Each preschooler’s photo and “voice” were uploaded to the digital display and were programmed to rotate throughout the day. The digital frame was placed in an accessible area within the classroom so that preschoolers could have access to their work throughout the day.

Discussion

Our project offers several important methodological adaptations for conducting participatory research with young children, particularly in the context of Photovoice. We successfully modified the traditional SHOWeD method to accommodate the developmental needs of preschoolers, providing hands-on assistance with camera operation and simplifying questions based on teacher input. This adaptation maintained the essence of the SHOWeD method—eliciting meaning and fostering reflection—while making it practical for use with young children. By allowing children to discuss their photos in real-time, we facilitated immediate engagement and reflection, demonstrating how participatory techniques can be effectively tailored to involve even the youngest participants in meaningful ways. Our approach aligns with and contributes to the growing literature on Photovoice adaptations for preschool-aged children (Butschi & Hedderich, 2021; Gilbert, 2023; Shaw, 2020). These methodological adjustments not only showcase the flexibility of participatory research methods but also expand the body of knowledge on conducting such research with young children, offering valuable insights for researchers working with this age group.

It is important to note that research can be collaborative, or action driven, without being participatory. The existent literature highlights that there are many interpretations of what is meant by participatory with some researchers using the term loosely, failing to align with the true definitions and values of participatory research (Key et al., 2019). The current study, however, aimed to implement a participatory project among preschoolers and their lead teacher. In Table 1 we summarize how we mapped the CBPR principles to our initial plans and expectations for conducting the research and actual implementation of the project. While we used the CBPR principles as guidelines for our plans and had certain expectations, in reality, some of those plans were adjusted over time. During this study, we identified key takeaways significant for researchers aiming to implement PR in preschool classrooms.

A Case for Engaging Preschoolers in YPAR

Engaging preschoolers in YPAR offers an opportunity for promoting early participation and empowerment for social change. While traditionally focused on adolescents, extending YPAR to preschoolers, like the current study intended, nurtures critical thinking and problem-solving skills from an early age. By involving young children in identifying and addressing issues within their immediate environment—such as classroom dynamics or play areas—YPAR validates their perspectives and fosters a sense of autonomy and responsibility (Gray & Winter, 2011; Harder et al., 2013; Lundy et al., 2011). This approach not only enriches children’s educational experiences but also contributes to creating inclusive and democratic learning environments where young voices are heard and valued (Lundy et al., 2011; Rivas-Quarneti et al., 2024). Our results suggest that, children’s photos and narratives about their favorite areas of the classroom can be useful for the lead teacher to design more responsive and child-centered curriculum. Through age-appropriate methods like storytelling, drawing, or role-playing, preschoolers actively contribute to research, offering unique insights that can enhance both their own development and educational practices overall (Maconochie & McNeil, 2010; Tisdall et al., 2023).

Engage Early and Sustain Involvement over a Longer Period

Reflecting on our study, it was remarkable that we built sufficient rapport with just a couple of class visits. In general, the preschoolers were very open and welcoming towards us. However, project data collection and implementation may have benefitted from us spending more sessions with the children, particularly with shy children. Researchers should remember to be flexible as they plan to engage children with different temperaments and personalities (Gray & Winter, 2011; Lundy et al., 2011). We recommend that researchers start early and allocate ample time to complete study logistics including obtaining necessary permissions to work with the youth (e.g., vaccination documentation; background checks) and scheduling implementation. Waiting until the design is finalized to begin addressing logistical constraints may not leave enough time, especially if challenges occur and hiccups emerge. We also recommend rapport building occur upon IRB determination and site administrative, teacher, and parent approval. Time is needed to foster trusting partnerships with schools and youth, leading to higher quality results as children feel more comfortable sharing their perspectives.

We were able to do this in several ways. First, we engaged the school administrator early in conversations about the project as it was being conceptualized. We learned from them how and when to engage teachers. In our case, the administrator wanted to speak with teachers to gage interest and then introduced us to the lead teacher. Second, we met with the lead teacher to introduce the concept of the project, ask for initial thoughts about it and feasibility, and listened to suggestions for changes and other considerations. Third, we maintained regular dialog with the lead teacher and periodic short check-ins with the administrator (who also checked in with the teacher regularly) to gain insights and direction. Last, based on the lead teacher’s guidance, we built trusting partnerships with the children on their terms, in their environment, and on their schedule. We spent multiple sessions building rapport and trust with them in their classroom and on the playground with activities they chose (e.g., legos, bike riding, playing catch).

Center Flexibility and Developmental Appropriateness in the Project

We recommend that future studies carefully consider how children’s developmental stage(s) influence their ability to participate in YPAR activities. It is essential to provide age-appropriate tools and training. For example, younger children may struggle with using professional cameras so point-and-click cameras may be more suitable. Preschoolers can actively participate in data collection and interpretation through methods such as group discussions, placing stickers on a picture survey, and responding to visual representations of survey results (Lundy et al., 2011). Alternative modes for children to share their experiences should also be considered. For instance, incorporating a show-and-tell activity could allow students to bring in objects they want to discuss or share their project experiences in other ways. This approach can make participation more accessible and enjoyable for all children, leading to more meaningful and rich data. Expanding participatory research to include toddlers (aged 1 – 3 years) could also provide new insights (Maconochie & McNeil, 2010). Engaging toddlers can be done in multiple ways including the Mosaic approach, brainstorming ideas of topics that interest them during class time, observing their natural curiosities to gain initial insights for suggestions, and working with near peers (preschoolers) to assist in the research process. Using PR with toddlers and preschoolers helps understand these developmental stages and can inform the design and implementation of age-appropriate activities and learning environments (Tisdall et al., 2023).

Consider Community Assets, Bidirectional Learning, and Integration of Knowledge

We recommend that researchers actively engage with multiple members of their community partners. These individuals can offer unique insights on how to effectively engage youth participants and help bridge the researcher-youth relationship. Collaborating with preschool teachers requires sensitivity and clear communication to align research goals with their teaching focus on child development and education. Bidirectional co-learning was vital to our project, benefiting researchers (e.g., understanding early childhood development), teachers (e.g., learning participatory research methods like Photovoice), and preschool students (e.g., using cameras and describing assets).

Staff and teachers at CDLs already use evidence-based practices that support young children’s developmental needs (Tisdall et al., 2023). Researchers should leverage this existing knowledge when collaborating in educational settings. By doing so, researchers can help build capacity for participatory research and support the development of child-centered curricula. To achieve this, researchers must provide scaffolding and context for participatory research, demonstrating its application possibilities to teachers and preschoolers. This approach will facilitate a collaborative and integrative process, enhancing the educational experience for all participants.

Managing Expectations: Develop a Strategy for Power Sharing, Capacity Building, and Sustainability

It is crucial to introduce at an early stage and periodically remind community partners how decisions made during the research process are informed by PR principles. This promotes transparency and fosters scaffolding community partners’ knowledge of PR guidelines and methods. For instance, we realized that the lead teacher thought co-authorship on a publication implied additional work and time commitment, which was not something she was interested in adding to her plate. After further reflection, we acknowledge that had we framed and worded the invitation to co-authorship differently, we might have gotten a different response. It was a lesson learned on how to better communicate within the partnership. In addition, engaging teachers in conversations about what types of research would be most useful and beneficial for children and the school community is important for ensuring relevance of the topic and partnering with teachers in the conceptualization. This is a practice we undertook previously with teachers in this school (Dariotis et al., 2025; Soto et al., 2024).

Regularly revisiting PR principles may reinforce their importance and foster a shared sense of ownership and commitment to research goals and partnership. Moreover, researchers should actively involve community partners in capacity-building activities, such as training sessions and workshops, to enhance their skills and knowledge (Gray & Winter, 2011; Tisdall et al., 2023). We incorporated capacity-building activities through weekly meetings with the lead teacher and the development of child-friendly protocols that can be used in the future. This involvement empowers partners to co-lead projects and increases their investment in the project’s success. By recognizing and valuing the unique expertise that community members bring, researchers can create a more equitable and mutually beneficial partnership.

Sustainability should also be a key consideration from the outset, if appropriate. Some projects may be “one and done,” but often researchers and community partners want a longer-lasting partnership. Researchers should work with community partners to develop strategies for maintaining the project’s impact after the research concludes. This could include creating resource guides, establishing ongoing support networks, and identifying opportunities for continued collaboration on future projects. By planning for sustainability from the outset, researchers can help ensure that partnership benefits endure after the initial study is completed.

The methodological lessons learned and recommendations from our study offer valuable insights for promoting preschool classroom participatory engagement in future research. To build on this understanding, future studies should consider incorporating debriefing interviews with teachers, administrators, and children to gather diverse partner perspectives, further informing best practices and recommendations. There is also a need for proper funding and infrastructure support within classrooms to effectively engage in PR projects, thus supporting sustainability of PR in classrooms. Evaluating the sustainability of these methods within classroom settings is crucial to ensure long-term benefits and effective integration into educational practices.

Strengths

Our study expands the application of participatory methods to early childhood education contexts. Utilizing qualitative methods, the study provides in-depth insights into the participatory process from multiple perspectives. This approach enriches understanding of how participatory methods can be effectively implemented in preschool settings. Our study fostered co-learning by building research skills among teachers and enhancing children’s abilities in communication and expression through photography. The study emphasized inclusive and multifaceted dissemination strategies, including digital displays for preschoolers and an E-brochure for parents and administrators. This ensured that research findings would be accessible and beneficial to all stakeholders involved.

Limitations

The study involves a single preschool classroom with a relatively small sample size (n=19 students) within a university-based preschool. This limits the generalizability of findings to other preschool settings with different demographics and contexts. Due to time constraints and feasibility, preschoolers did not participate in all research phases such as developing the research question and research design. Additionally, adherence to staff ratio requirements meant that our collaboration was primarily with the lead teacher. Including teacher assistants and undergraduate student assistants in our project would have been advantageous, especially considering instances when the lead teacher was unavailable due to breaks or planning time. Expanding the involvement of staff would have strengthened our relationships and enhanced the project’s sustainability.

Conclusion

This project was undertaken to design and implement a PR project as part of a graduate level participatory research methods course. Our study uniquely centers the perspectives of preschool aged children utilizing an arts-based Photovoice approach. We applied PR approaches in a preschool classroom, an understudied setting relative to other educational contexts, where studies typically focus on assessment and basic research (Groundwater-Smith et al., 2014; Jacquez et al., 2013). Our project provides evidence for the feasibility of engaging a preschool classroom in participatory research methods. We were able to conduct this research despite time constraints, logistical barriers, and additional safety procedures necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. PR studies involving preschool classrooms represent a valuable contribution to the field, expanding the utility and benefits of these approaches.