Introduction

Individuals with acquired brain injury (ABI), such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and stroke, are at an increased risk for obesity and obesity-related comorbid conditions (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, recurrent stroke) than people without an ABI (Dreer et al., 2018; Forman-Hoffman et al., 2015; Fryar et al., 2020). Reasons for weight gain and obesity in this population are complex (Driver et al., 2021) and may include decreased mobility, cognitive impairment, low self-efficacy, hormone imbalance, decreased social support and accessibility to healthy food and accessible fitness facilities (Driver et al., 2021). Notably, few evidence-based programs to promote weight loss and health for people with TBI and stroke exist (Driver, Juengst, et al., 2019; Driver, Swank, et al., 2019).

To address this need, in 2015 and 2018, our team used a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to engage partners (e.g., people with TBI or stroke, care partners, clinicians, researchers, community members) in the modification of the evidence-based and CDC-recognized Diabetes Prevention Program Group Lifestyle Balance (DPP-GLB) for people with TBI (GLB-TBI; 2015) and stroke (GLB-CVA; 2018) (Driver, Juengst, et al., 2019; Driver, Swank, et al., 2019). The DPP-GLB is a 12-month, 22 session healthy lifestyle program. Our team’s primary modifications included (1) reduced curriculum content, (2) inclusion of care partners to provide support, (3) focus on movement versus steps for physical activity, (4) incorporation of subject matter experts (e.g., physical therapist, nutritionist) to teach sessions and answer questions, and (5) focus on heart heath (GLB-CVA only) (Driver et al., 2017, 2020). Importantly, during pilot testing of the GLB-TBI in 2016 (Douglas et al., 2019; Driver et al., 2018), feedback from our partners and participants consistently encouraged the addition of peer mentors to promote participant engagement and provide informational, social, and emotional support from the perspective of a person with lived experience of an ABI. In response, our team made additional adaptations to incorporate peer mentors into program delivery.

Peer mentoring is considered the relationship between two people who share common characteristics, experiences, or health conditions in which one person provides support to the other (Aterman et al., 2022). Incorporating peer mentors to provide informational, emotional, and social support for health conditions such as cancer (Anderson & Armer, 2021; Lim et al., 2020; Sezgin & Bektas, 2022), depression (Shorey & Chua, n.d.), kidney disease (Bennett et al., 2018; Ghahramani, 2015), lupus (Williams et al., 2017), and diabetes, is heavily cited in the literature (Aterman et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2017). Evidence on the impact of peer mentoring for people with neurological conditions, such as TBI and stroke, is promising, yet limited (Aterman et al., 2022). In a 2022 scoping review of the literature (n=53), 9 studies described peer mentor interventions for TBI and 6 for stroke. Of these studies, most focused on the transition from rehabilitation to home and reported participant outcomes such as improved health, confidence, social and self-management skills. Noticeably, however, there are no reports of peer mentors being formally incorporated into weight-loss or healthy lifestyle interventions for people with ABI living in the community (Aterman et al., 2022).

Therefore, the purpose of this manuscript is to (1) describe our team’s process of incorporating peer mentors into the delivery of the DPP-GLB modified to meet the unique needs of people with TBI (GLB-TBI) and stroke (GLB-CVA), (2) present participant exit survey data on the perceived helpfulness of mentors, (3) share perspectives from select peer mentors about their role, and (4) discuss opportunities for improvement and next steps.

Methods

Peer mentors were incorporated into the GLB-TBI and GLB-CVA interventions which were delivered as part of two randomized controlled trials (RCT) approved by our institutional review board and available on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03594734; NCT03873467). The protocol papers for each are published elsewhere (Driver, Juengst, et al., 2019; Driver, Swank, et al., 2019). The GLB-TBI RCT (n=57 participants) was delivered using an attention control condition and the GLB-CVA (n=65 participants) was delivered using a 6-month wait list control condition.

Interventions

The GLB-TBI and GLB-CVA are modified versions of the Diabetes Prevention Program Group Lifestyle Balance (DPP-GLB) (Driver et al., 2017, 2020). The DPP-GLB is an evidence-based (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group, 2002, 2004; Hamman et al., 2006; A. Kriska, 2003; A. M. Kriska et al., 2006), theoretically grounded (Bandura, 1989; Hochbaum et al., 1952), healthy lifestyle program designed for delivery in group-based community settings such as churches, community centers, and healthcare systems (Ackermann et al., 2008; Amundson et al., 2009; Davis-Smith et al., 2007; Katula et al., 2011, 2013; M. K. Kramer et al., 2009, 2010; S. F. Kramer et al., 2013; Vadheim et al., 2010). The DPP-GLB consists of 22 sessions delivered over a 12-month period. The program tapers over time (12 Core sessions delivered weekly, 4 Transition sessions delivered bi-monthly, and 6 Support sessions delivered monthly) and the goal of the program is to promote 5-7% weight loss by reducing calories and fat and increasing physical activity (150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity each week). Sessions are delivered by coach interventionists who undergo a standardized 2-day training offered by the Diabetes Prevention Support Center (DPSC) (Mk, 2009; Venditti & Kramer, 2013). Participants are encouraged to self-monitor food and physical activity using a tracking log each week with feedback provided by the coach. Examples of session topics include (1) Healthy Eating, (2) Move Those Muscles, (3) Problem Solving, (4) Managing Slips and Self-Defeating Thoughts, (5) Ways to Stay Motivated, (6) Mindful Eating, Mindful Movement, (7) Manage Your Stress, and (8) Balance Your Thoughts. A comprehensive review of the DPP-GLB, session topics, and necessary adaptations to meet the needs of people with TBI and stroke, and participant eligibility criteria can be found elsewhere (Driver, Juengst, et al., 2019; Driver, Swank, et al., 2019).

Peer Mentors and Their Participation in the GLB Interventions

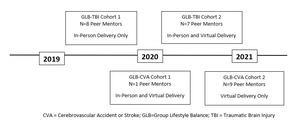

We partnered with twenty-five peer mentors aged 25-70 years (19 female, 6 male) who had lived experience with brain injury (either TBI or stroke, n=21) or were a care partner of someone with a brain injury (n=4) across both interventions. Peer mentors were required to have experience with the GLB-TBI or GLB-CVA, be willing to attend up to six sessions (maximum) over the course of the 12-month, 22-session intervention, and have an interest in leading a healthy lifestyle. To avoid overcrowding (e.g., multiple peer mentors attending the same session), a schedule was sent one month before the interventions started with session topics, dates/times of sessions, and curriculum material. Sessions were chosen by peer mentors based on experience with the topic and preference for the date and time. Peer mentors were financially compensated for their time ($100 per session or $600 total). Sessions were taught both in-person and virtually. For GLB-CVA, only one peer mentor was involved in the first of two cohorts. Figure 1 displays a timeline of peer mentor participation in both interventions.

Peer mentors met with coach interventionists one week prior to their assigned session for 30-60 minutes to review session material and assign specific sections or pages for the peer mentor to either teach or contribute to. For example, peer mentors were assigned to participate in specific demonstrations such as adapted physical activity, mindfulness, or cooking. Peer mentors would also prepare to give their own personal experience with lesson material (e.g., how they managed to meet their calorie goal while eating out, or how they exercised with injury-specific accessibility needs).

During their assigned session, peer mentors provided informational, emotional, and social support to participants. They would share their own experience leading a healthy lifestyle post brain injury and strategies for overcoming barriers to a healthy lifestyle. In addition to teaching session topics and leading demonstrations, peer mentors also answered questions posed by participants throughout the session. After the session was complete, peer mentors and coach interventionists would meet to provide feedback on how the session went and opportunities for improvement. Peer mentors also provided optional support to participants through a private Facebook group and email correspondence.

Peer Mentor Engagement Over Time Based on Feedback

Peer mentors were first introduced into the GLB-TBI program in January 2019 and their engagement increased significantly from 2019 to 2021 based on feedback from both participants and peer mentors. For example, in the first GLB-TBI cohort in 2019, peer mentors were invited to attend sessions, share their experience of living a healthy lifestyle, and answer questions. They did not assist the coach interventionist with delivering the session. However, in response to participant feedback and their desire to have peer mentors more involved in the sessions, peer mentors began assisting the coach interventionist with session delivery in latter cohorts (2020-2021) for both GLB-TBI and GLB-CVA interventions. Additionally, our team incorporated post-session meetings with peer mentors to seek their feedback on how session delivery went and opportunities for improvement, which were then incorporated into future sessions.

Participant Feedback Through an Exit Survey

At the end of the 12-month intervention period, participants in the GLB-TBI and GLB-CVA were asked to provide feedback on their experience in the program and suggestions for improvement through an exit survey. Participants completed the exit survey on their own, without the help of a research team member, and returned it using a pre-paid envelope or electronically via a secure REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) link (Harris et al., 2009, 2019). The survey included six questions that participants scored on a 5-point Likert-scale rating peer mentor helpfulness with items ranging from 1 (“very unhelpful”) to 5 (“very helpful”). Participants also completed 3 open-ended questions that addressed (1) success in the program ("Do you think you would have been successful in the program without Peer Mentors? Why, Why not?"), (2) relatability of Peer Mentors (“How much did you relate to the Peer Mentors? If you were to choose qualities, what would you look for?”), and (3) suggestions for improvement ("Would you recommend that future groups include Peer Mentors? Why, Why Not?"; “How else do you think Peer Mentors could have been helpful?”). Participants were reminded up to three times via email and text to complete the survey and some participants chose to answer some but not all questions. Exit survey data were evaluated with counts and medians to summarize Likert-scale data and open-ended responses were collected and tabulated.

Results

Participant Exit Survey Data on Perceived Helpfulness of Peer Mentors

Due to the different study designs of the GLB-TBI and GLB-CVA, 28 participants were enrolled in the GLB-TBI intervention (RCT with attention control; n=29 in attention control) and 65 were enrolled in GLB-CVA (RCT with 6-month wait-list control). Only participants in GLB-CVA Cohort 2 (n=22) received exit survey questions as Cohort 1 only had one peer mentor and responses would not be anonymous. Due to study attrition (17-20% across both RCTs) and the voluntary nature of the exit survey, 17 participants completed some components of the GLB-TBI exit survey (60.7%), and 10 participants completed some components of the GLB-CVA exit survey (45%). Likert-scale data for helpfulness of peer mentors for program components are shown in Table 1.

Exemplar quotes from the open-ended qualitative questions are summarized in Table 2.

Feedback from Select Peer Mentors on Their Role

Our team sought the feedback of four peer mentors who participated in our GLB-CVA (n=2) and GLB-TBI (n=2) on their perspective of their role. These peer mentors were engaged due to their continued involvement in our program of research and interest in providing constructive feedback to our team. Open ended questions asked included, (1) “Why did you want to be a peer mentor?” (2) "What did you learn?" (3) "When did you feel most valued?" and (4) “How would you recommend that peer mentors be included/involved in the future?” Commentary from the peer mentors is aggregated below.

Why did you want to be a peer mentor?

Peer mentors noted that individuals with brain injury are more likely to accept help if it is from someone who understands the recovery journey. While therapists and researchers may understand the mechanisms of the recovery process, unless they have lived brain injury experience, they do not know what it is like to experience, first-hand, the doubt, anger, loneliness, and grief over the change in one’s life due to the trauma of brain injury. Coaches who do not have lived experience cannot always relate to the thoughts that participants have of “will I be the same as I used to be?” Peer mentors all cited the desire to help people who are recovering from brain injury to get the most out of the GLB program and gain strength to continue their recovery journey.

What did you learn?

Peer mentors noted that they learned a lot by teaching others and that being a peer mentor helped them become more understanding of others’ journeys. For example, one peer mentor noted that even though individuals may seek out help, it does not mean that they are prepared for all that comes with the GLB journey and, as peer mentors, it is their job to be patient and understanding. They also noted that recovering from a brain injury is a scary time and you are relearning things that you have taken for granted most of your life, including leading a healthy lifestyle. Therefore, patience must come from both participant and the coach/peer mentor. Peer mentors noted that they were able to see different viewpoints on brain injury recovery which, in turn, helped them on their own journey.

When did you feel the most valued?

Peer mentors felt valued when their perspectives were heard, and they were able to make connections with participants. One peer mentor noted that while everyone came from a different background, they all shared a commonality of brain injury and had shared victories and experiences that only they could understand. Peer mentors also felt valued at the end of the program when participants would share their experiences and gains over the 12 months. Peer mentors felt that they played a role in those achievements.

How would you recommend that peer mentors be included/involved in the future?

Peer mentors recommended having separate meetings just for peer mentors to share ideas and resources. They also suggested creating a resource guide for participants from experiences they have had. For example, a resource with shared recipes or physical activity adaptations. They all agreed that it is important for GLB participants to have examples of individuals who have been on the other side of the recovery and healthy lifestyle journey, and this is where peer mentors fit in.

Discussion

Our team successfully incorporated 25 peer mentors (people with lived brain injury experience and care partners) into two 12-month healthy lifestyle and weight-loss interventions for people with TBI and stroke. Exit survey data from participants were positive and many participants found peer mentors to be helpful (e.g., providing support for lifestyle changes, feeling motivated or inspired to lead a healthy lifestyle, increasing physical activity, eating healthy foods, and problem solving). Qualitative data from participants generally supported these findings with many participants feeling as though they related to peer mentors ("I found I was able to relate to the mentors because they faced similar obstacles such as complications with certain exercises"), and would recommend that they be involved in future groups (“They help normalize the process and show that it can be done!!”, “They provided me with much needed inspiration”). Importantly, data from the GLB-TBI and GLB-CVA RCTs, of which the peer mentors were a part of, revealed that participants lost weight (5-8%) and attended classes (>85% attendance) (Driver et al., 2022, 2023). Though the studies were not designed to examine relationships between peer mentor involvement and participant weight loss or engagement (e.g., attendance in sessions), we believe this is an important next step. While the incorporation of peer mentors as trained coach interventionists (e.g., as peer interventionists) has been shown to be feasible in other DPP-GLB programs (Kulik et al., 2015; Mizushima et al., 2021; Young et al., 2017), the feasibility of incorporating peer mentors in GLB programs for people with TBI and stroke has not been tested.

It has been shown previously that engaging peer mentors in the co-creation of physical activity and health behavior programs leads to reciprocal benefits for both participants and mentors, with evidence for increasing autonomy and reducing physical activity barriers for adults with brain injury, resulting in increased physical activity participation and important physical, psychological, and social benefits (Quilico, 2023). This notion is supported by feedback from our select peer mentors who told us that being a peer mentor helped see different viewpoints on brain injury recovery which, in turn, helped them on their own journey.

Importantly, by incorporating principals of CBPR throughout the research process (e.g., planning, modifications, intervention delivery, and post intervention discussions), we were able to improve the integration of peer mentors throughout the intervention period. The incorporation of peer mentors in the GLB-TBI and GLB-CVA interventions was introduced by our former participants, many of whom became peer mentors, and was sustained and enhanced through continued feedback from both participants and peer mentors. We believe that this collaboration strengthened the quality of our research and will hopefully lead to a more sustainable healthy lifestyle program for people with brain injury.

Limitations and Future Directions

The GLB-TBI and GLB-CVA interventions were designed and powered to detect weight loss and health benefits for participants (Driver, Juengst, et al., 2019; Driver, Swank, et al., 2019) and not to identify benefits for peer mentors. This is a limitation but also an important future direction. Future research could benefit from formal incorporation of peer mentors to evaluate the impact of peer mentors on participant engagement and outcomes as well as peer mentor outcomes. Additionally, opportunities exist to further expand peer mentor engagement by training peer mentors to become certified DPP-GLB coaches and coach interventionists in the GLB-TBI and GLB-CVA interventions. This would allow peer mentors to lead entire sessions independently. We believe this in an important next step in the sustainability of the programs.

Funding

This manuscript was supported by two grants from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant numbers 90DPTB0013 and 90IFRE0021). NIDILRR is a center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this manuscript do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.