Introduction

The integrative nature of relationships between human well-being and health and animal welfare is increasingly recognized (Arluke, 2021; Rauktis, Lee, et al., 2020; Ryan, 2014; Silva & Lima, 2019). The One Health (Zinsstag et al., 2021) and One Welfare (Pinillos, 2018) frameworks used in public health, veterinary and human medicine identify the intersections between humans, animals and the environment. These frameworks and the One Health/Welfare research identifies the positive intersections for human well-being (Kretzler et al., 2022; Muraco et al., 2018; Purewal et al., 2017; Ryan, 2014) as well as the undesirable impacts of these intersections (Arluke, 2021; Obradović et al., 2020; Rombach & Dean, 2021). However, the connection between these intersections and how they are related to the social determinants of human health (SDH) and well-being was not well explicated until McDowall et al (2023) created a complementary framework for outlining how human SDHs impact animals, specifically pets (i.e. companion animals). Integrating SDHs with the One Health/Welfare frameworks provides a clearer path to understanding what preventative policies related to SDHs can protect the human-animal bond (McDowall et al., 2023).

Economic stability is one of the five domains of SDH (McDowall et al., 2023, p. 5) and encompasses employment, income, expenses, debt and medical expenses. This SDH impacts pets in terms of the human’s ability to pay for veterinary care, food, and time spent with animals. For example, individuals working long hours or those with multiple low-paying jobs may be unable to spend time exercising or being a companion to their pet (Arluke & Rauktis, 2024). Similarly, individuals may struggle to afford veterinary care without incurring debts (Arluke & Rauktis, 2024; Blackwell et al., 2024). At a macro-level, living in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods means less access to pet resources and veterinary services (Reese & Li, 2023).

Moreover, economic stability can affect an owner’s ability to provide appropriate food for their pets. In this paper, we provide an overview of the existing literature on the intersection of economic stability and access to pet food, the development of a pet food pantry to address pet food insecurity, and a case example of the use of human centered design (HCD) to improve the distribution process at the pet food pantry. This case study also includes suggestions for how human and animal centered designs can be used to create services and support to mitigate the negative impacts of human economic stability on pets.

Economic Stability, Nutrition for Companion Animals, and Access to Pet Food

As a SDH, employment, income, savings and debt impact human health and the resources available to care for the companion animal’s wellness (food, medical care and companionship (Arluke, 2021; Arluke & Rauktis, 2024; McDowall et al., 2023, p. 5). Providing an adequate and healthy diet for pets is a major source of stress for low-income pet guardians (Arluke, 2021; Arluke & Rauktis, 2024; Fink, 2015; Rombach & Dean, 2021). Pet owners go to great lengths to keep their pets fed. The most frequently identified strategies when pet food is scarce are to feed their pets their human food, offer smaller amounts of pet food, trade with neighbors, borrow money and seek out pantries where pet food is distributed at no or low cost (Rauktis, Lee, et al., 2020). However, this comes at a cost to owners who report anxiety and emotional distress because of worries about being able to feed their pets (Arluke, 2021; Rauktis, Lee, et al., 2020). Rombach and Dean (2021) identified this as “pet food anxiety” and found that individuals who actively engage with their pets experience higher levels of pet food anxiety. Thus, engagement with animals, thought to be a positive determinant of health, may also create negative states of emotion which may result in negative states of stress and a rehoming of the animal.

In a study of commitment to pets, Rauktis et al. (2021) found that financial costs of veterinary care and food were a major factor in considering ongoing pet ownership, even when there was a deep level of attachment between humans and their pet. Other studies estimate that between 30% to 50% of pet owners who were relinquishing their animals said that having low-cost or free pet food available would have prevented them from relinquishing their animal (Russo et al., 2021; Weiss et al., 2015).

Pet Food Pantries

Pet food distribution through special food distributions from shelters or inclusion in human food pantries are common solutions to addressing the consequences of economic instability and improving human and animal food security. Pet food distribution in human pantries has been found to be an effective method of improving human food security (Rauktis, Lee, et al., 2020). In their cross-sectional study of 30 human and pet food pantries in Western Pennsylvania, the authors found that animal owners using pantries with pet food reported greater food security than those with pets who did not have access to a pantry with pet food. The qualitative findings of the study found that pets were a powerful motivator for securing human and pet food, yet a source of anxiety because pet food supplies in the pantry or shelter often fluctuated and what is given may not last until the next pet food distribution. The outbreak of COVID-19 negatively impacted global pet food supply chains and increased prices at a time when people were more likely to be unemployed or partially employed. A study done by Ghanian researchers found that 47% of households with animals were unemployed during the pandemic and increased pet food prices changed feeding patterns in a negative way (Dogbey et al., 2024). In the United States special pet food distributions by charities (e.g. Greater Good) and corporations (e.g. Pet Smart) occurred during the pandemic. However, as the estimated 53 million households continued to struggle to feed their families in the post COVID-19 economy, (Feeding America, 2022) the need for free or low-cost pet food remains as critical as it was during the height of the pandemic.

Ellie’s Pet Food Pantry

Ellie’s Pet Food Pantry (hereafter known as Ellie’s) is a community service offered through Humane Animal Rescue of Pittsburgh (HARP), an urban shelter for domestic animals. HARP shelters dogs, cats and small animals, provides low-cost spay and neuter services as well as low-cost wellness and veterinary services. As part of community outreach services, HARP offers free pet food and supplies monthly to enrolled low-income pet owners who then visit one of the two locations to pick up food: the East site (i.e. “East”) and the North site (i.e. “North”). The pet food that is distributed by staff and volunteers comes from community, charity and corporate donations. However, the volume of community food depends upon donations, and so the volume can vary from month to month. Despite the supply and demand challenges, Ellie’s has been operating continuously since 2010, and the scope of services and number of families served every year has increased so that in 2023, 1,469 patrons were served, a 10% increase over 2022. In 2024, 2508 patrons were served– a 50% increase. Currently there are over 600 patrons in Ellie’s database, with an average of 250 households served per month in 2024.

To be eligible for food, owners must enroll in the program, which entails providing contact information, the number and species of pets owned, and assurance that their pets have been spayed/neutered. While active in Ellie’s, if pets are not spayed/neutered, the owners agree to have their pets spayed/neutered and to not acquire additional pets. Participants were contacted periodically to update their information and to verify the number of pets and their health status.

Background of Case Study

Although Ellie’s was designed to supplement pet food purchased by owners, the economy after the COVID-19 pandemic was one of rising costs and unemployment in the region. Many pet owners have come to rely on Ellie’s as their only source of pet food (Arluke & Rauktis, 2024). Six hundred and seventy patrons obtained an application and applied for Ellie’s in 2024. Having more patrons as well as the additional paperwork required for new sign-ups increased the time spent waiting, leading to cars lining up an hour or more before the start of distribution and long lines of cars waiting to get into the North location that blocked shelter parking. Additionally, some people picked up food for multiple households, and seeing the load for 10+ households go into one car escalated other patrons concerns that there would be nothing left for their pets. Consequently, the food anxiety described in the research became apparent and manifested in angry patron behavior and a sense of stress and urgency. It is not surprising that the staff and the volunteers began to dread Ellie’s days– an activity that previously had been personally fulfilling.

A recent study of community focused shelter workers found that they chose this work because they want to address the needs of both species, and most of their work was spent in securing basic resources for pets and humans (Vincent et al., 2025). However, the same study found them seeking help for feelings of burnout and concerns about quality-of-life issues for animals (Vincent et al., 2025). Concerned about the process and impact on the staff morale, the Director of Community Programs asked for assistance from a volunteer in Ellie’s who was trained in human-centered work to assist the team in (1) examining how to make Ellie’s more effective in promoting health and wellbeing of animals and the patrons and staff and (2) how to make the food distribution process more efficient and equitable. The other volunteer who worked on this paper was a board member, familiar with HARP’s mission and resources.

Human-Centered Design

Human-Centered Design (HCD) evolved from the design world and has been used in multiple disciplines (computer science, engineering, health care) at the micro, mezzo or macro levels (see Gottgens & Oertelt-Prigone, 2021). HCD is often thought to be a single method, but Gottgen’s review found that it entails a wide array of design methods and techniques to be used selectively depending upon the design case and the context. While there are many definitions of HCD in literature, the commonalities are that it is a repeatable, creative approach to problem solving that brings together what is desirable from a human point of view with what is feasible and economically viable (IDEO, 2015). IDEO’s design framework labels the phases as the inspiration phase followed by ideation and then implementation.

A problem or issue is the starting place, and the process is characterized by short timelines, rapid reiteration cycles with draft prototypes and inclusion of stakeholders/constituents. Due to limited time and resources at HARP, the decision was made to start the HCD sessions with staff and volunteers first since the design sessions could be slotted into existing department meeting times of the community team. As noted above, HCD includes a wide range of methods and while the process is consistent, how it is labeled and communicated and what is considered when choosing a method is flexible. For this case study, we followed the best practice standards of human-centered design cycle of the International Standard for Organization (ISO) 13407: plan (i.e. understand the context); specify the user and organizational requirements; produce design solutions; evaluate against requirements; and iterate. The problem statements for this case study were:

How can we make Ellie’s Pet Food Pantry more effective in promoting health and wellbeing of animals and humans (patrons and staff); and

How can we make the distribution process more efficient and less stress-inducing for patrons and staff?

Methods

Planning; understanding the context of the problem

Method: Field study observations

Because the facilitator was also a volunteer, the first step was for the facilitator to conduct a field study. The field study began in December 2022 at Ellie’s East and North on distribution days, allowing almost 12 months of observation before the design sessions started in October 2023. This was not planned but was fortuitous as it provided a long period of observation of how the staff and volunteers worked within the physical spaces, the workflow, how weather impacted processes and how the patrons interacted with the staff and helped to give a deeper understanding. Although a formal data collection process was not in place, the facilitator kept voice memos and messages, and emails were shared with the Ellie’s staff to document observations after each distribution.

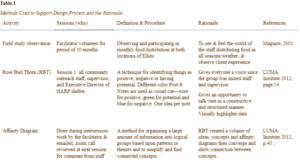

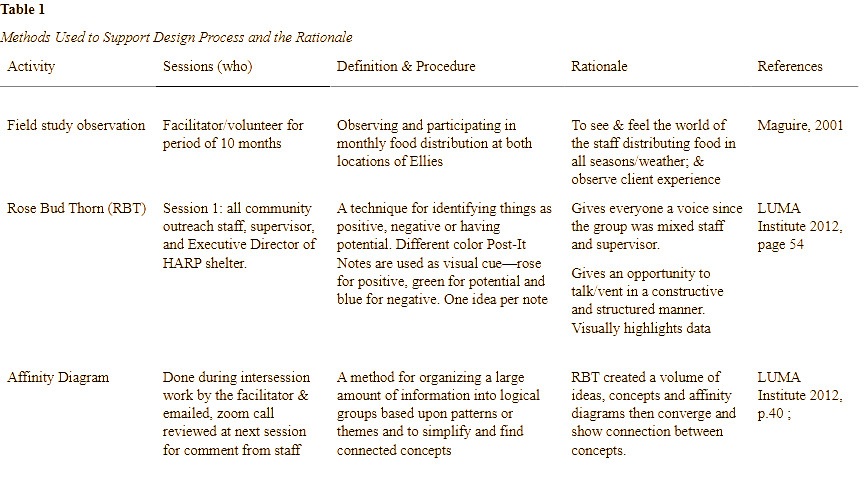

Table 1 displays the Methods Used to Support Design Process and the Rationale for the Methods by session and who attended. The team consisted of the Director of Community Programs and two community staff members. The three-person team was responsible for the daily community-focused work. In the first session all interested staff at HARP were invited to participate and the director and two staff were joined by the Executive Director of HARP and an assistant in the development department who often helped with the distribution. In the two sessions held in person, only the three team members participated in the facilitated sessions.

Specify the user and organizational requirements

Rose Bud Thorn

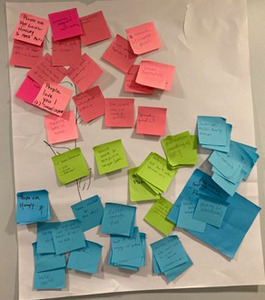

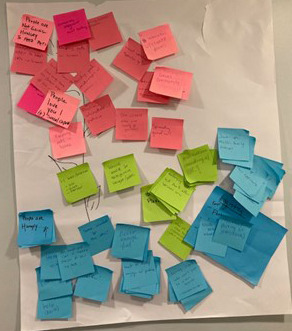

In this stage we started with an exercise called “Rose, Bud and Thorn” (RBT Luma, 2012). Rose Bud Thorn (RBT) was chosen as a method to provide a structured way for everyone in the sessions to express what they saw as positives, negatives and what had potential. For this method, participants write one “rose”, “bud” or “thorn” per post-it-note, which are then posted up on the wall. The post-it-notes are anonymous, can be moved to create groups, are a safe way to express feelings, and the colors highlight what the overall group mood may be (Figure 1). The anonymity of the post-it-notes was particularly important since the mix of supervisors and staff could have led to participants feeling uncomfortable expressing feelings aloud as in a focus group or typical brainstorming session. Another benefit of this method is when feeling negative or frustrated, RBT requires participants to think about the positive aspects and what negatives have the potential to change. It was observed that while completing the RBT activity, participants expressed the desire to address the whole pet, just not food needs (i.e. making sure that pets can access spay/neuter services and vaccination). It was also observed that the discussion during the RBT activity helped to re-affirm that for all the frustration and stress, 99% of the patrons were positive, thankful for Ellie’s and that this service was valuable and valued and that they could address a broader set of needs. Additionally, during this session the facilitator also highlighted points of intersection and diversion between the year of field observations and the RBT notes.

Affinity diagraming

The second method used in this stage to organize the input from the RBT was “affinity clustering” or "affinity diagraming. Affinity clustering is a common next step after a RBT session for finding relationships between concepts as well as divergence and taking a lot of information and reducing it into manageable areas. The facilitator did this after the session and then confirmed the groupings at Session Two.

During session two, participants verified several clusters, such as the lack of technology resources and the uncertain food supplies. The team felt that the most important clusters to address were (1) behaviors related to food anxiety (e.g. long wait times and low supplies) and (2) lack of volunteers which was a challenge and a potential "bud. An important group observation that emerged from two work sessions and verified by field observation was that relationships between patrons and the staff developed over time. Ellie’s patrons know the staff and trust them: when staff are off sick or on vacation patrons ask about them, and it is not usual for them to ask to speak to the staff about animal or human concerns. Similarly, the Ellie’s staff worry when they don’t see a regular patron for several months. These relationships were felt to be critical not only in addressing anxiety but also in engaging them to obtain veterinary wellness, care and care for themselves. A second important point that came up in the discussion at the second session was that patrons were genuinely concerned about their pets and focused on their pets having enough to eat, with any negative emotions expressed were the result of this focus.

Allocation of Function and Map of Space

The final method was creating “maps” of the physical spaces of both North and East and combining this with field observations of the facilitator. The maps were created in between sessions and shared at the second session.

Produce Design Solutions

At the second session, after looking at and discussing the affinity diagrams and the maps, the team decided to develop solutions to address patron anxiety about food and to increase the usefulness of volunteers because this was where solutions could be put into place quickly with little financial investment and then refined or discarded as they were implemented.

Round Robin

Using the Round Robin technique, the team brainstormed ideas to address patron anxiety and volunteerism, pinpointed what would be problematic, and developed final solutions (Luma, 2012). Regarding patron anxiety, the first brainstormed ideas grew from the observation that contact with the staff was observed to be helpful. The initial idea was that as soon as people pulled into the parking lot to have a staff person greet them and then do a paper check-in. This check in would involve verifying the name, number of pets, and changes to the pets as well as identifying cars with new patrons, pets with problems or special diets, or patrons picking up multiple households. Round Robin helped to pinpoint what could be problematic: a staff person meeting everyone meant that the only staff would then be tied up and not able to float to problem solve when issues arose. The final solution was to create a welcoming sign as people pulled in to set the stage:

Welcome to Ellie’s Pet Pantry

Please stay in your car

Take only what you need

First time? Let us know!

Be kind - We’re working hard for yinz! (Pittsburgh term for you)

The second idea was a pet needs order form, which could improve efficiency and thus reduce anxiety and waiting times for patrons. The form could be completed while waiting, given to a volunteer, and the food could be prepared in the storage area in advance. Round robin helped to identify what information should be on the order sheet, the need for training the volunteers on the form, and the importance of animal needs. Round Robin also helped to pinpoint what could be problematic and what would help: literacy and building relationships. The final solution was that this form would be completed by a volunteer as part of a conversation with the patron, allowing the volunteer to provide reassurance and preparation if supplies were low. This would also allow the volunteer to gather pet information (e.g. pet sickness, in need of care, needs to be spayed/neutered) and then have the floating staff member talk with the patron. This information gathering would also address the problem of needing to update the patron information in Ellie’s database. As the final part of the Round Robin for this idea, a prototype form was completed. Finally, as part of the Round Robin the team created an orientation sheet for volunteers with “roles” and “tasks” and asked the Volunteer Manager to find two to three volunteers who would commit once a month to Ellie’s rather than the single day of service corporate volunteers that had been sent in the past. The volunteers are then emailed prior to distribution days with their role and are asked to respond. Thus, volunteers who were there every month were familiar with the patrons and in time viewed as trustworthy and competent.

Implementation and Iteration

A prototype order form created at the second session was implemented in the East and revised before December distributions and used at both sites in December. Additionally, four- or greater- household pickups were asked to make appointments to pick up their food. However, even with these changes the limited space in the North remained a problem; cars were still backing up onto the major highway. Therefore, in March of 2024, an additional distribution day was added to the North so that patrons could come on either the second or last Wednesday of the month. Before adding the day, an informal poll was taken of patrons in the North and the feedback was that they would be willing to come midmonth to reduce congestion and waiting times.

As identified in the RBT design session, additional days, the order form, and building relationships required teams of consistent and trained volunteers. Consequently, Ellie’s worked with the volunteer director to recruit a core group of volunteers for each site. A set of written training materials was tailored for both sites and before distribution days the volunteers assigned to the North and East site were emailed with the instructions, their role and how to perform the task. Moreover, HARP became an internship placement site for several universities with an MSW and a public health student assigned to Ellie’s as interns. Since January 2024, the volunteers at each site have been consistent, and the patrons recognize them, adding a sense of trust and community.

Although a formal evaluation of these changes has not been carried out, informal feedback suggests that the patrons are pleased with the changes, and waiting time in line has been reduced. The entrance sign welcomes returning patrons, orients new ones and asks them to tell staff and volunteers as soon as possible if they are unenrolled. This information results in immediately enrolling them through a paper form and flagging the staff person to introduce them to the new patron. We have observed that within a 45-minute period, approximately 45 cars (including cars with two or three households) were served. In the past it would have taken 90 minutes. While distribution is still busy, the level of stress is markedly lower, and the team meets immediately after a distribution to debrief. This meeting is critical to building relationships with the patrons and communicating information to the other members of the team (Mr. S was in the hospital this month or Z’s dog is being destructive; can we find enrichment toys next month) as well as building relationships and morale within the team. Several new light touch interventions that are being piloted in 2025 are written materials for follow-up visits for the clinic with name and phone numbers/emails and distribution dates. They have also examined some back-office procedures, shifting data entry of the logs to a volunteer so that a staff person can address animal needs documented rather than spend time on data entry.

An important aspiration voiced during the first design session was that Ellie’s would become an entry point to an array of wellness services for the animals, as well as a connection point for their humans. Therefore, starting in 2025, distribution days at North and East were arranged back-to-back, so that all three staff would be present at each distribution day rather than splitting up at the two sites. The hope is that greater face-to-face contact beyond the transaction of receiving food will build relationships, allowing for more in-depth engagement about animal and human needs. Other ways of connecting with patrons are more frequent emails from the staff and when enrolling them in Ellie’s, helping them to access other services that they could be eligible for such as heating assistance and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Animal alterations have increased because funding was obtained specifically for Ellie’s patron animals, removing the financial barrier. Over 100 animals have been altered using this funding. Moreover, Ellie’s animals are referred to the Humane Health Coalition, a One Health Mobile Clinic, for free pre-surgical exams and then scheduled into the clinic for spay/neuter, removing one more barrier.

Discussion, Limitations and Recommendations

In the hands of community groups such as HARP, HCD can build relationships and has the potential to address social determinants of health, and create equity (Holeman & Kane, 2019). We found that using HCD methods helped to build empathy for the patrons, engage the staff in creative ways and most importantly identify the pets as ultimate constituents of Ellie’s. The anxiety and stress experienced by both the staff and the patrons was driven by the fear that the animals would go hungry. Through centering animal needs first on the order form, conversing with patrons about pet needs, and being transparent about supplies available thereby managing expectations and building on relational rather than the transactional engagement, Ellie’s was able to create a less stressful experience for everyone. Other changes, such as signage, consistent and trained volunteers, staff who could float and scheduling additional days helped to reduce waiting times and long lines which reduced patron stress. Moreover, these solutions were implemented with little cost to the organization and rapidly with ongoing review and adjustments. The team became engaged and curious and continued to look for ways to improve and to address their goals of human and animal health. By using HCD we have improved Ellie’s, allowing 35 tons of food to be placed into community homes more efficiently and with less stress, increasing the chances of food security for both species. More animals have been spayed/vaccinated or expedited into veterinary care and the staff have begun to enjoy their work again and feel that they are making inroads in health and wellness for low-income pet households.

There are several limitations to this case study that serve as a launching point for additional evaluation. First, the patrons of Ellie’s were not formally included in the design sessions due to the sprint timing of the design work to make the changes as quickly as possible. However, as patrons waited for food, the volunteer facilitator talked informally with them to get their input about the changes implemented such as the additional dates and signs as well as those that were being considered. If funding can be secured, future work could include a patron survey, focus group, auto-ethnographic methods such as vignettes, or arts-based participatory approaches such as photovoice, to better capture the point of views of volunteers, shelter staff, and Ellie’s patrons.

Second, while understanding the needs of the user and co-partnering is a cornerstone of HCD, the animal users of a pet food pantry are not able to co-design in a HCD manner. Animal-Centered Design (ACD), a complementary process, focuses on the nexus between animals and technology from an animal-centered perspective, centering animals in the process of making choices and exerting control over their environment to meet their needs and preferences. Animals are the ultimate users of the pet food pantry, but it is impossible for them to “shop” in the warehouse. Moreover, the chaotic nature of distribution could be anxiety- producing and potentially dangerous, and so the animals who come to the pantry with their humans remain in their cars (with windows open for pets and treats). However, the human patrons of Ellie’s are aware of their animals’ allergies and preferences and request different brands and types of food. In this manner, the human is acting as a proxy for the animal as a co-designer. While this was included in the design work for this case study in terms of thinking about how food preferences and needs could be met (Personal Conversation with Clara Mancini, March 11, 2025), future evaluation could employ ACD to more directly incorporate animal preferences into Ellie’s.

The positionality of the “volunteer” HCD facilitator was both a positive and a negative in this case study. While being a volunteer provided a deeper understanding of the context, it was a challenge to stay in the facilitator role and not be part of the discussions other than to add observations, reframe questions but not offer opinions. Summarizing alone and then presenting to the team was not ideal, but staff availability was very limited. Only three community team members for a large county need meant that the staff was very busy and had very limited time to meet. To keep the process transparent and engaging, any out of session work done by the facilitator was reviewed via email and brief zoom calls. Without a formal evaluation, it would be premature to identify a “best practice” for pet food pantries from this case study. As noted by Arluke and Rowan in their book Underdogs (2020), shelter and animal welfare practices are embedded in the context of the community, region and nation state. However, we believe that human design processes implemented by animal welfare organizations in partnership with community stakeholders is a best practice that will increase transparency, keep the focus on animals and identify important contextual factors which can lead to creative and more effective solutions.

One of the most pressing challenges that shelters are currently facing is the increasing admission of animals after a record low of 5.5 million animals in 2020. Between 2022 and 2023, the number of animals waiting to get out of shelters increased by 177,000 (Economic hardship Reporting Project, 2024). The social determinants of health impacting humans are also impacting their companion animals: many animals in shelters are there not because they are unwanted, but because their guardians lack basic resources–for themselves and their pets (Russo et al., 2021; Weiss et al., 2015). By working with communities using participatory methods and, listening to what is wanted, rather than what shelters have, then shelters change their narrative of “animal rescue” to “protecting the human-animal bond”, keeping companion animals in their families and communities.

Funding

No funding sources were used to support this work.

Ethical Statement

Design information was kept private and not shared outside of the design groups except with permission. All members of the design team reviewed this manuscript and gave permission to publish it.

Data Sharing

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgements

University of Pittsburgh Clinical and Translational Science Institute for their training support in design work.

Authors and contributions

The first Author was responsible for writing along with the second author. Third and fourth reviewed and corrected and co analyzed results.