Introduction

Greenspaces are a quintessential feature of the urban landscape in the UK. The need for public urban parks in the UK was first conceptualised in the nineteenth century. The 1833 Select Committee on Public Walks was set up to address the provision of open spaces for recreation in increasingly industrialised cities. The genesis of the idea for public parks emphasised a motive to address concerns for public physical and moral health. This concept was known as ‘rational recreation’ and centred on the idea the working classes needed parks to draw them away from undesirable pursuits such as drinking and gambling (O’Reilly, 2019).

While the premise of rational recreation was of social engineering and control in a top-down approach from an active middle-class trying to inculcate their own values and behaviour in a passive working-class, an important factor in the genesis of public parks was the demand from the people themselves which is often neglected in a retrospective look at the history of parks. Some municipal local authorities established a public subscription system for their parks, and this may indicate a demand for them existed within the city residents. Working class representatives actively raised money at their workplaces to fund public parks. O’Reilly (2019) is of the opinion this nineteenth century working-class activism proves parks were historically established collaboratively with the community who used the space and their ‘evolving ideas about citizenship and social responsibility’ (p. 137). She uses Heaton Park as a case study for this and highlights a key characteristic of the shift from a Victorian park to an Edwardian Park was one where citizens took on active roles in the park. The presence of community-based active citizenship roles in urban greenspace today, in the form of Friends of Parks Groups, is only a natural continuation of that.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, austerity policies in the UK made an increase in voluntary sector groups delivering public services necessary (G. Jones et al., 2016). This gave rise to concepts known as user participation, active citizenship and participatory governance in greenspaces. Such forms of community-led initiatives are also much needed from a social sustainability perspective, as participation in urban greenspace brings communities together, increasing social cohesion (Veen, 2015). Additionally, research shows participation has benefits over top-down approaches, like legislation, in ending social exclusion and injustice (Nwachi, 2021).

Context of the Study

NFPGS

The National Federation of Parks and Green Spaces (NFPGS) is an organisation that supports volunteer groups in the urban greenspace sector. Constituted in 2010 to be the voice of Friends of Parks Groups (commonly called Friends Groups), the NFPGS believes in promoting benefits of urban greenspace throughout the UK and supports grassroots movement of over 7,000 local Friends Groups.

While provision and maintenance of urban greenspace falls under the jurisdiction of the local authority in the UK, public budget and funding cuts have rendered Friends Groups necessary, as they not only provide voluntary hours of labour but can also apply for funding to maintain their local greenspace. Groups can be constituted with a Chairperson, Secretary and Treasurer or they may be un-constituted. Friends Groups typically consist of a core group of active members, and a larger supplementary network of volunteers/members/supporters that are not involved in the day-to-day activities of managing the park but can be called upon as the need arises, for organising events, litter-picking etc. To maintain this network, Friends Groups establish links with community groups such as schools, religious groups, local businesses, and other volunteer groups.

The NFPGS aims to ensure Friends Groups are a true representation of the community, embodying inclusivity, and diversity. As such, they saw a need to conduct research to uncover good practice that Friends Groups had undertaken to be more diverse and inclusive and form a blueprint for other groups in the network to use. This led them to partner with a community research initiative at University College London (UCL), where graduate students and organisations from the voluntary sector are brought together to carry out mutually beneficial community-engaged research.

The purpose of this paper is not to share the findings of the study, but rather focuses on the process of this graduate student researcher’s collaboration with community partners to co-produce research on a sensitive and relevant topic.

For the scope of this research, it was co-decided with NFPGS partners to focus specifically on ethnic diversity. Attention to cultural diversity leads to community empowerment, greater citizenship, gives citizens a sense of their rights to include their own cultures in the broader urban realm (Low et al., 2009, p. 17) and creates place attachment in people for parks which can result in pro-environmental behaviour (Ramkissoon et al., 2012).

Existing Research on Friends Groups in the UK

Current literature on Friends Groups focuses mostly on their partnerships with local authorities, participatory management of parks, place-keeping, and community involvement (Crowe, 2018; R. Jones, 2002b; Mathers et al., 2015; Nam & Dempsey, 2019; Speller & Ravenscroft, 2005; Whitten, 2019). Friends Groups in the UK have a significant position in their communities. Jones (2002a) showcases the success of the eight Friends Groups in his study to effectively entice residents back into parks characterised by degradation.

However, pertinent to the research topic of ethnic diversity, Kim and Roe (2007) who studied Friends Groups from an empowerment perspective, emphasise the issue of inclusiveness in Friends Groups as one needing ‘urgent consideration because of the growing cultural mix in many urban areas’ (p. 48). They see inclusivity being so vital for Friends Groups, it will shape whether they manage to stay relevant to their local communities in the future. Concern for community representation in Friends Groups is echoed by Whitten (2019), as well as Mathers et al. (2015) who highlighted in their extensive study of seven Friends Groups, that groups were highly effective and skilled in organising events creating local engagement, but observed there was underrepresentation of ethnic minorities. They also observed Friends Group members themselves recognised they were unrepresentative of their local community. Almost all the groups in their study reported they found it difficult to attract people from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Friends Groups rely solely on volunteers to conduct their activities and operations. Studies confirm people from ethnic minority backgrounds are less likely to volunteer than ethnically white people. This is consistent with findings from studies in the UK (Hylton et al., 2019) where Friends Groups exist, US (Bortree & Waters, 2014) and Canada (Smith, 2012). Intersectionality also comes into play here because individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to be from low socioeconomic backgrounds and people from low socioeconomic groups are less likely to volunteer (Hylton et al., 2019). Ethnic minorities may also face other barriers such as a lack of skills or resources (Wilson, 2000) or feel disinclined to volunteer for other reasons such as an erosion of their cultural values (Warburton & Winterton, 2010). Making volunteering accessible is essential because of the proven benefits it has on health and wellbeing (Binder & Freytag, 2013; Oman, 2007) and provides a means to address social and health inequalities for those most at risk of social exclusion (Southby & South, 2016).

Theoretical Foundations for the Methodological Approach

Participatory Action Research (PAR) is an approach that is characterised by research emphasising ‘active collaboration through participation between researcher and members of the system, and iterative cycles of action and reflection to address practical concerns’ (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020, p. 3). The goal is often not just to generate knowledge but also to create real and lasting social change that addresses particular concerns of the community. Key to a PAR approach is community members and researchers co-designing and co-creating some or all of the research process (Chevalier & Buckles, 2019). Participatory approaches are well-suited for research contexts that are complex and have diverse participants, as it allows for the co-construction of knowledge in a way that is culturally sensitive and gives marginalised communities the chance to give voice to their experiences (Bustamante Duarte et al., 2021; Finney & Rishbeth, 2006) resulting in design justice (Costanza-Chock, 2020). PAR is underpinned by the core principles of co-creation, such that community members are actively involved in the knowledge creation process by designing, implementing, and interpreting the study; democratic and equitable collaboration, ensuring the research is an inclusive and joint endeavour; and social transformation, as it allows community members to create real-world impact (Lake & Wendland, 2018; Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020).

Knowledge is situated (Haraway, 1991) and the positionality of the researcher is a pertinent factor in any study. This involves introspection and recognition of uncomfortable truths perhaps raising questions around power, ethics, and representation. However, it is morally beneficial to address these issues transparently and openly admit them while capturing the research process, as stated by McDowell (1992) who believes ‘we must recognise and take account of our own position[…]and write this into our research practice’ (p. 409). Understanding my positionality as a researcher through this research study was a vital exercise for reflexivity which is considered an essential component of qualitative research particularly. Hibbert et al. (2010) define it as a ‘process of exposing or questioning our ways of doing’ (p. 48) and it is a critical component of participatory methodologies. Reflexivity is a continuous process of critical reflection and self-examination, whereby researchers must scrutinise how their values, socio-economic positions and assumptions may affect the power dynamics of their interactions with participants and the outcomes of the research (Patnaik, 2013). In reflexive participatory action research, the researcher is not considered a detached objective observer, but rather it is acknowledged that the researcher’s own identity, biases and experiences shape the research in substantial ways. Potential effects on the research are mitigated by a continuous process of self-aware questioning and reflecting on assumptions, while being transparent about the researcher’s positionality to establish trustworthiness in the study (Kingdon, 2005). By embracing reflexivity, participatory action researchers can better navigate their dual roles as both researchers and collaborators, simultaneously strengthening the research process and increasing the credibility of findings due to the transparency.

Critical and feminist research methodologies challenge power dynamics and aim to give voice to marginalised groups in order to conduct research that is more inclusive, and also actively work to dismantle systemic inequalities and social injustices, while calling for situating the researcher as they shape the results of their analyses through their own lenses (Haraway, 1991; Harding, 1987, p. 9), making them similar in commitments and principles to those of reflexive Participatory Action Research (Cahill, 2007; Ozano & Khatri, 2018; Robertson, 2000).

Participatory, reflexive, critical and feminist approaches can be brought together in a methodology that allows for transformative research and models the kind of inclusive and participatory practices that this research study seeks to encourage in Friends Groups – indeed becoming a microcosm itself of the social change its output aims to achieve. By deliberately designing the research process to mirror the principles being advocated for and mindfully embody the aims of the study, the research becomes not just an exercise in knowledge creation but also a practical demonstration of the very transformative social change it seeks to bring about.

Research Design

This study was conducted with a strong commitment to Participatory Action Research (PAR), employing reflexivity and intentionally designed to mirror the intended research outcome of inclusion and participation of ethnic minorities in urban greenspace, embedding the principles that underpin the study within the methodology itself. The research was undertaken working closely with three community partners - the chair of the NFPGS and a Friends Group in London, a voluntary advisor at the NFPGS and the chair of a Friends Group in Birmingham. These community partners were engaged in every phase from defining the research scope and questions to interpreting the results.

Reflexivity and Researcher Positionality

I undertook this research topic because as a member of an ethnic minority community myself, inclusivity in public space is a subject of particular interest to me. Growing up as a Third Culture Kid (Dillon & Ali, 2019; Pollock et al., 2010) in the expatriate world of the Middle East, I was used to being in a marginalised minority. Attending an international school and living in an expatriate-only gated community, living concurrently with privileges but without basic rights, I had friends and acquaintances from over 50 countries by the time I was an adult – navigating diversity and cultural differences with ease and curious to understand others’ perspectives. I have often seen myself as a bridge between cultures, similar in many ways perhaps to second or third generation immigrants and believe this has formed my ability to look at issues with objectivity and an expanded worldview.

During my research, I tried to be cognisant of the fact my non-UK background and my distinct worldview are different to the UK-specific context under study. I continually gave thought to how my background positioned me as a researcher, particularly in relation to my research partners and research participants. During the research process, I felt myself sliding frequently between ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ perspectives (Mullings, 1999). This helped me to question certain aspects of the methodology and make adjustments based on those reflections.

I adopted the reflexivity approach of Corlett and Mavin (2018) as a ‘self-monitoring of, and a self-responding to,’ my ‘thoughts, feelings and actions’ (p. 377) through my research process.

I chose to undertake this study with a strong commitment to PAR specifically because it is well-suited to solving real world problems and community-driven social change, which is what I hope the research achieves. Also, the topic of ethnic diversity is a sensitive one and can invoke feelings of defensiveness or discomfort. PAR makes the process collaborative and co-produced and enables incorporating insight from partners to make the research as comfortable as possible for those involved.

Throughout my research I made sure to constructively share power, collaborate and co-produce with my community partners, recognising they had knowledge and insight I did not, which would inform the research beneficially.

Methods

This research used an exploratory mixed methods design (Creswell & Clark, 2018; Creswell & Creswell, 2017; Martha et al., 2007) with qualitative data collected and analysed. The NFPGS previously, in 2020, conducted an online network-wide ‘Better Friends Survey’ to gather data regarding groups’ composition, attitudes, management, links to their communities and activities. A dataset from these survey results between September 2020 to July 2021 was analysed. Responses to Likert scale questions were assessed to identify groups that valued diversity in their groups and greenspaces and qualitative answers to free text questions were analysed to identify groups that indicated an intent to improve diversity or initiative(s) undertaken to improve diversity.

A questionnaire was administered to the 140 groups identified, of which 118 groups that had indicated valuing diversity were sent a mass email with a link to the questionnaire and the remaining 22 groups that had hinted at undertaking some diversity initiative(s) were sent a customised email that referred to their responses in the Better Friends Survey. The questionnaire collected further detail about groups’ initiatives to improve ethnic diversity specifically and was completed and submitted by 26 Friends Groups.

The questionnaire results were analysed with the following parameters to identify groups for interviews, (a) Groups indicating an ethnic minority diversity improvement initiative undertaken, (b) Groups indicating a significant general diversity initiative in free text question, (c) Groups reporting an improvement in ethnic minority participation after initiative. This analysis identified seven groups for semi-structured interviews, but one declined to be interviewed.

The resulting six groups from which a representative was subsequently interviewed were from different parts of the UK (Birmingham, London, Bradford, Manchester, Liverpool, and Gloucester) and the percentage of ethnic minorities residing in their respective local areas varied. Two groups were located in areas where the ethnic minority community was actually a majority in the ward, while the other four groups were in areas where the ethnic minority community was a minority in the overall local community. These six groups had all undertaken some sort of initiative to improve ethnic minority participation, for example, employing a park-keeper of ethnic minority background, as one Friends Group did, or setting up meetings with groups of local ethnic minority women to discuss what they needed from the greenspace, as another Friends Group did.

Purposive sampling was used for both questionnaire and interviews so descriptive insight could be collected from information-rich respondents (Patton, 1990). The initiatives these participant Friends Groups undertook to achieve self-reported improvement in ethnic minority participation, were indicated in the questionnaire answers and elaborated on in the interviews.

Using an inductive approach in grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014), a thematic analysis was done on interviews to identify patterns across the dataset following the steps outlined by Braun and Clark (2012). Themes were extracted from the patterns and used to formulate recommendations. Table 1 details the methods used and outlines the PAR collaboration and co-production with community partners in each phase.

Research Output

The aim of this research was to provide the NFPGS with practical recommendations Friends Groups could use to improve ethnic minority participation in their groups and greenspaces. In order to produce a usable community product from the academic study that could be easily distributed and adopted across the Friends Groups network, the research findings were used to create a simple and accessible ‘toolkit’, with an easy-to-understand and engaging graphic to sum up the themes, called the Recommendations Palette, shown in Figure 1.

The Recommendations Palette visually illustrates the concept of diversity and suggests that Friends Groups must get creative to formulate their ethnic minority participation improvement strategies, as a one size fits all strategy cannot work. In line with Amin (2002), who sees success resulting from local context and local energies, a foundational recommendation is suggested to first analyse current ethnic minority participation levels and understand the local context (denoted by the palette itself). The Palette was accompanied by a Participation Level Checklist to help Friends Groups employ this foundational recommendation, which the two NFPGS community partners formulated, as well as a table of various recommendations against each theme (Table 2).

Mirroring the Research Aims Within the Methodology Through a PAR Approach

PAR approaches inherently align with the principles of inclusivity and participation, making the research topic of this study – ethnic minority inclusion and participation – not just the topic being studied but also enabled the active modelling of these principles within the research process.

Employing PAR enriched my own ability to approach the study with the needed sensitivity and understanding of the research context. Given the sensitivity of the topic and the potential for participant discomfort or defensiveness around discussing or revealing action or inaction to address ethnic underrepresentation, it was vital to build a research environment of trust and comfort. Using PAR, my community partners were invaluable in providing insight on how best to phrase questions in the questionnaire, craft an email in the most encouraging and transparent language, as well as helping me to understand the exact reasons why this topic was sensitive in the context of Friends Groups, which helped me greatly in interacting with participants during interviews.

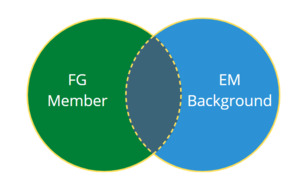

Initially, the research began with two community partners who were both of White-British ethnic backgrounds and members of Friends Groups. I, being from an ethnic minority background and an international student in the UK, did not have detailed understanding of the lived experience of an ethnic minority background citizen. Because of the conscious effort to question my positionality throughout the research, I realised we were addressing the question of ethnic participation in Friends Groups, but the research itself lacked the voice of a person from the group we were hoping the research would affect.

And so, a Friends Group member from an ethnic minority background was invited into the research process to better inform the study and embody ethnic minority inclusion and participation – the intended research outcome – within the methodology itself. This partner was a member of the group we were hoping for the research to effect social change in and who was involved in a Friends Group (the desired outcome of the good practice we were concerned with) as illustrated in Figure 2, thereby making the research process a microcosm of the principle the study was advocating for and mirroring the research goals. Additionally, a richer study would have ‘the potential to contribute to longer-term processes of societal change’ (Mahony & Stephansen, 2017, p. 43),

Incorporating reflexivity enhanced the research by ensuring the inclusion of relevant voices with lived experience of the topic being studied. This informed the research process beneficially and upheld the commitment to PAR, characterised by the ‘co-construction of research through partnerships between researchers and people affected by and/or responsible for action on the issues under study’ (Jagosh et al., 2012, p. 311).

Community partners were engaged in every step from defining the scope of the research and refining research questions to interpreting the results and co-creating the recommendations framework. In Phase 1, the community partners’ organisation, the NFPGS, had already done some data gathering and generated reports and had great input into how to best use that data for the purpose of our research questions.

In Phase 2, the community partners were heavily engaged in the process of reaching out to their community to recruit participants for the research. This empowered them by giving them the agency to use language and phrasings they felt would be best received by their fellow community members. This phase required that I reflect on the power dynamics of the collaborative research process and ensure I shared power in a constructive way aligning with PAR principles.

In Phase 3, although I analysed the responses to questionnaires, the community partners contributed their insight into the analysis parameters and in designing the recruitment process for the relevant groups identified from the results of the questionnaire.

In Phase 4, the choice to send a list of questions to participants prior to the interview was influenced by community partner suggestion for reasons outlined in Table 1. This illustrated how ‘academic-community partnerships… work together to make choices that…best meet the needs of both the research and those involved in the research’ (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020, p. 5). This phase also became a key moment of adaptation in the research process. Exercising reflexivity brought about the inclusion and engagement of our community partner from a South Asian background. This added an additional lens to the study which was incorporated in the formulation of the interview questions, with specific questions added as a result of discussions with him.

Phase 5 and 6 of the study involved conducting the thematic analysis and social media content analysis which I carried out and kept the community partners informed of.

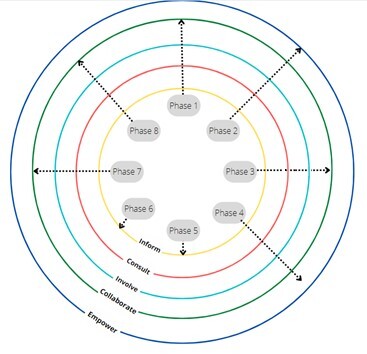

In Phase 7, the findings from the thematic analysis were discussed at length with all the community partners and they interpreted these through their own unique lenses and valuable perspectives. This resulted in refining the findings and arriving at the final themes. In particular, the community partner from an ethnic minority background was able to confirm some of the findings from the perspective of ethnic minority communities. For example, regarding the finding of the Facilitation theme, he corroborated that facilitating inclusion in the way the participant Friends Groups had where ethnic minorities could be their authentic selves, without compromising their cultures or beliefs, enables minorities to feel comfortable sharing ideas and stepping up for leadership roles which would help slide them higher up the participation spectrum which was co-decided to look like Figure 3. Core Group Member represents the highest level of involvement with a Friends Group. We mindfully mirrored this correspondingly in our methodology, aiming for the highest level of ethnic minority participation in our research process, by recruiting our ethnic minority community partner to be an essential collaborator and contributor to the study.

And finally in Phase 8, all community partners helped in the formulation of the recommendations and helped to ensure the research output would be a practical, usable community product that Friends Groups would be able to easily deploy and benefit from. It is a fundamental element of PAR to produce findings that can be turned into actionable outcomes that create positive change. The NFPGS community partners created a self-audit checklist that Friends Groups could use to analyse their current ethnic minority participation levels and we created a recommendations framework that could be used once they had evaluated this.

Borrowing Vaughn and Jacquez’s (2020) ‘Participation Choice Points in the Research Process’ diagram[2], I visually summarise the levels of community partner participation employed in Phases 1-8 in Figure 4[3]. Vaughn and Jacquez’s description of levels is mentioned in Figure 5, where ‘Inform’ is the lowest level of participation and ‘Empower’ is the highest.

Navigating the Challenges of Diverse Perspectives

Because the community partners had different backgrounds, they inevitably had varying perspectives which added value to the research process. However, simultaneously, their different backgrounds also sometimes manifested in their desire to frame the study in different ways. The White British community partners emphasised their desire for the research to have a positive framing. They advocated for this success-focused approach because they felt that this had the greatest chance of being well-received by Friends Groups in the network. Due to the sensitivity of the topic of ethnic diversity they felt taking an encouraging approach that positively framed successes the studied Friends Groups had achieved, would inspire other Friends Groups to follow best practice. They argued taking a critical approach that focused on asking Friends Groups (whose membership is often majorly made up of the White British, middle class demographic) why they were lacking ethnic diversity in their groups and greenspaces would achieve nothing other than making these volunteer groups feel defensive and uncomfortable.

In contrast, our ethnic minority community partner was someone who was from the underrepresented group we hoped our intended research outcome would eventually benefit. Being someone who had overcome the barriers to participation by himself, his approach was more critical and hinted at an underlying frustration with the current approaches of Friends Groups. This unique lens added value to the research process, albeit while adding an additional layer of challenge in balancing the positive, success-focused framing with the need to incorporate the critical perspective of our ethnic minority community partner.

We continued to take a positive, success-focused approach to the study firstly because this achieved the goal of filling a gap in the research. There is already a lot of research on the barriers to participation in greenspaces faced by minorities, but a relative paucity of studies that address what has worked to improve ethnic minority inclusion and participation in greenspaces. Secondly, because this study was to, ultimately, provide a blueprint and guide to Friends Groups that they could use as a springboard to act on ethnic minority inclusion and participation, framing it in an encouraging and inviting manner made the most practical sense.

Although we continued with the positive framing of the study, as it had the most value in offering relatable and actionable solutions to Friends Groups, our ethnic minority community partner’s perspective was not disregarded. The reasons in favour of a positive framing were discussed in detail with him and he agreed that for the research output to have the best chance at being embraced and put into action by Friends Groups it made sense to frame the study in a way they would be most receptive to. Though it was not the primary focus of the study, his more challenging and provocative approach to the study, provided an invaluable lens through which to collect and examine the data, even while maintaining the positive framing. Because while the research scope and questions had been designed to emphasise successful initiatives and practices, the critical lens brought by the ethnic minority partner added a layer of depth to both the interviews and subsequent data analysis and interpretation, ensuring his views and insights were given their due respect and value.

Key Learnings for Structuring Participatory Research that is Diverse and Inclusive

Working on this research with both ethnically White British and ethnic minority community partners revealed the challenges of balancing different perspectives in the participatory process. A key learning for myself as a researcher was in leading the process to a clear and decisive framing of the study without neutralising the diverse perspectives of community partners. Researchers conducting participatory studies should acknowledge different lived experiences can lead to tension in key decision-making, requiring researchers to be sensitive facilitators that create space for honest dialogue and mutual learning, while building consensus.

Reflexivity was a key driver in making the research process an inclusive one. One of the most tangible outcomes of practicing reflexivity in this study was the realisation that the research process lacked the diverse participation the study hoped to encourage, leading to the decision to recruit an ethnic minority community partner to take part in the research. Participatory research studies should incorporate structured checkpoints for reflexive assessment of the voices shaping the research process and make adjustments to ensure the voices of communities that the research outcomes are intended for, are present. Reflexivity as a conscious exercise encourages critical questions to come to light. For example, after the study was completed, one of the White British community partners at the NFPGS reflected on how the framing of the study might have been very different if the output had been targeting ethnic minority organisations as its audience, rather than the Friends Groups who overwhelmingly come from a White British, middle class background. Such thoughtful reflection will hopefully feed into future plans and initiatives the NFPGS undertakes to engage ethnic minority communities into Friends Groups and their urban greenspaces.

Lastly, while the inclusion of the ethnic minority partner definitely improved the participatory approach bringing much needed insight and depth to the study, it also highlighted the inherent challenge of representation. As no single person can fully encapsulate the diverse experiences and perspectives of a broad group, it is important to recognise the limitations of individual representation. For example, in this study the ethnic minority community partner agreed himself he believed he was somewhat of an exception in the ethnic minority community in that he had the kind of personality that motivated him to overcome barriers for himself, resulting in him being the chair of a Friends Group. Therefore, his insights may not necessarily represent the perspectives of ethnic minority community members who would be less inclined to self-actualise into greenspace volunteerism due to barriers our ethnic minority community partner did not have to overcome as a second-generation immigrant, such as a language barrier. Participatory research studies should be mindful of this limitation of individual representation and avoid oversimplifying identities by incorporating multiple voices from communities, wherever possible, especially marginalised ones, as there are often many intersectional nuances that affect participation.

Conclusion

The study described in this paper was set up to examine the self-reported success of Friends Groups in improving ethnic minority inclusion and participation in their groups and greenspaces. We used a reflexive Participatory Action Research approach to mirror the principles of inclusion and participation which the study aimed to promote. The goal for the NFPGS community partners who took the initiative to sign up with the community research initiative at UCL was to formulate recommendations that the UK-wide network of Friends Groups could use to improve ethnic minority inclusion and participation.

Engaging community partners in every phase of the research – from defining the scope and research questions, to the interpretation of the findings and subsequent recommendations – demonstrated a co-productive and collaborative process that reflected the perspectives of the communities the research sought to serve. The research process also yielded learnings for participatory studies researchers about the importance of finding balance between making key decisions during the study and incorporating the diverse perspectives brought in by the participatory approach, the critical purpose of reflexivity in participatory processes to ensure diverse and rich research studies, and being cautious of generalising the perspectives of one individual from a marginalised group to represent the whole group. Actively involving all community partners ensured democratic and equitable collaboration in the decision making, ensuring the study was a joint endeavour. And while all partners were in agreement on their commitment to greenspace volunteerism, this democratic collaboration was not without its challenges, and situations arose when diverse and opposing perspectives surfaced. In this study the tension was addressed by balancing the need for the study to have a positive framing with the critical perspective of the minority partner. Such experiences underscored the value of maintaining flexibility and exercising reflexivity in participatory research, allowing for the methodology to adapt to evolving dynamics.

The community members were empowered to facilitate social transformation within their communities by co-creating a usable community product, with actionable recommendations grounded in the lived experience of Friends Groups. This not only enriched the process itself but ensured the research will have real-world impact and initiate tangible social change. Additionally, by including a community partner from an ethnic minority background, the research process turned into a microcosm of the intended research outcome.

This paper provided an example of how the principles of ethnic minority inclusion and participation that underpinned the study can be mirrored in the methodology. The practices exhibited in this study contribute to the field of participatory research by demonstrating how research can be conducted in a way that actively embodies its objectives. By grounding the research process in the foundational principles being advocated, the study not only answered the research questions it set out to investigate but also created methodological approaches that were as transformative as the outcomes the study aims to achieve.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted as part of a dissertation for MSc in Global Prosperity at the Institute for Global Prosperity at University College London (UCL). Partnership with the National Federation of Parks and Green Spaces (NFPGS) was established through UCL’s Community Research Initiative.

I would like to thank my community partners Dave Morris, Paul Ely and Nadeem Aziz for their collaboration and engagement in this research. Their contributions were integral to the participatory process, shaping both the study and its findings. I appreciate the time, insights, and commitment they brought to this work.

Funding

The research reported here was funded by the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office in the UK, and UCL. The author is grateful for their support. All views expressed here are those of the author not the funding bodies.

Core Group Member refers to an officer, committee member, or trustee which represents the highest level of involvement with a Friends Group. Active Supporters refers to ethnic minority background members who are not part of the core group but still very active in the greenspace’s activities and events, supporting the Friends Group with volunteering. Active Links refers to the partnerships and contacts Friends Groups have with local ethnic groups that get involved in the greenspace and with Friends Groups. Usage refers to ethnic minority visitors to the park and has the lowest level of engagement with Friends Groups.

Note: Unlike in Vaughn and Jacquez’ literature, I did not use the level of participation to guide the selection of research tools.

Phase 4, indicates a participation level between collaborate and empower, because the participation of the Friends Group member of ethnic minority background greatly shaped the research and empowered the voice of the community the research hopes to impact.