Introduction

Participatory research and design with marginalized groups are grounded in the principle that those affected by a challenge have the right to define their needs and actively shape the trajectory of change. However, researchers struggle to involve children and young people in the most vulnerable or marginalized positions (Kennan et al., 2012; Nygren et al., 2017) and there is a risk that the apparent complexity of working with these groups deters researchers from including them (Clavering & McLaughlin, 2010; Irwin, 2006). A lack of consensus on what constitutes meaningful child and youth participation further complicates the translation of participation ideals into substantive health research involvement (Larsson et al., 2018). While there is a growing body of health research involving children and young people (Schalkers et al., 2015), their participation is often compromised by assumptions about their capacities to contribute, and biomedical perspectives focusing on treating or compensating for abnormality rather than exploring a target group’s preferences and goals (Clavering & McLaughlin, 2010; Njelesani et al., 2022; Stafford, 2017). Hence, participatory research may result in tokenism and disempowerment unless critical perspectives are incorporated (Todd, 2012). Acknowledging and addressing norms that exclude children and young people from influencing knowledge production means to shift focus from individual barriers within target groups to the external and contextual impediments these groups may face. Rather than merely compensating for these barriers, the aim should be to transform the norms that exclude them.

As health and design researchers we are convinced that participatory research methodologies are essential to enforce the human right of children to influence decisions affecting their bodies and lives in health contexts (Nations, 1989). However, participatory research (PR) often faces facilitation challenges related to intricate power dynamics and hierarchies, especially when engaging children and young people in marginalized or vulnerable positions (Benjamin-Thomas et al., 2024; Nielsen & Boenink, 2020; Teleman et al., 2022). When positions such as child, patient and/or belonging to a minority group intersect, there is a simultaneous marginalization by norms of different systems (Karadzhov, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021). Health researchers need to be aware of the social factors at play in the settings they create and acknowledge their responsibility to facilitate co-construction of data, or else they risk enforcing the exclusion that these children and young people already experience (Clavering & McLaughlin, 2010; Howard et al., 2021). The preference for recruiting proxies or the most articulate individuals (Howard et al., 2021) possibly reflects a dominance of adult-centric methods that heavily rely on verbal accounts, as well as a perceived lack of inclusive and flexible research tools (Clavering & McLaughlin, 2010; Njelesani et al., 2022; Stafford, 2017). Unintended consequences of such practices are the exclusion of marginalized populations from research and a reproduction of bias in knowledge production (Cook & Bergeron, 2019; Sevón et al., 2023). This is worrying since children in marginalized positions are likely to hold crucial insights into the excluding effects of power structures (Clavering & McLaughlin, 2010).

Researching diverse experiences implies a need to adopt diverse approaches and tools (Dan et al., 2019) and calls have frequently been made for the development of more inclusive tools and approaches to involve children and young people in marginalized positions in meaningful ways (Lam et al., 2020; Njelesani et al., 2022; Wärnestål et al., 2017). The growing range of creative research tools is promising but does not guarantee a truly participatory knowledge production (Montreuil et al., 2021). As highlighted in recent reviews of participatory methods and tools, many of these tend to limit children’s participation to data collection, while analyses and knowledge-sharing often remain adult-driven activities (Branquinho et al., 2020; Freire et al., 2022; Sevón et al., 2023). This implies that children’s perspectives are viewed and shaped through the lens of adult interpretations (Sevón et al., 2023). Approaches based on critical or emancipatory epistemologies can help redistribute power between actors when researching issues experienced by marginalized groups (Banas et al., 2019). Among the range of critical approaches, Norm Critique (or Norm Criticism) is characterized by its focus on norm awareness and enabling norm transformation by targeting and challenging marginalizing structures and norms. Norm-critical approaches have been applied within fields such as education (e.g. Castillo et al., 2024), design (e.g. Isaksson et al., 2017), and innovation (e.g. Wikberg Nilsson & Jahnke, 2018). A norm-critical approach is not about addressing one explicit norm, since it is rarely clear beforehand what specific norms operate within a given setting. Rather, the norm-critical process aims to convey the norms at play, how they interact, and how they direct actions and agency for different actors in a context. Scholars in the field of norm-critical pedagogy has further stressed the need for self-reflexivity and directing the gaze towards the actions of actors in powerful positions (in this case adult researchers or designers) (Kumashiro, 2015). Its reflexive stance on knowledge production makes norm critique especially relevant to PR involving children and young people, since norm-critical approaches can help elicit power dimensions, identify and overcome norm-related barriers in research or societal contexts, and prioritize marginalized perspectives in the development of products or services (Isaksson et al., 2017; Paxling, 2019; Wikberg Nilsson & Jahnke, 2018).

As far as we are aware, however, there are no studies that describe to what extent norm-critical aspects are reflected in health-related PR involving children or young people. Knowledge exchange regarding existing tools and ways to ethically adopt them may also be limited since PR researchers operate in different fields. This paper therefore pulls together method contributions from across disciplines with the aim to assist researchers in making well-informed method decisions and to stimulate reflexivity when planning and conducting participatory research and design with children and young people. By identifying what characterizes norm-critical approaches in PR, we will assess to what extent these are present and relate them to methods, tools, outcomes, rationales, and participation levels in the studies.

Methods

Study Design

The authors (four health and design researchers with backgrounds in industrial design, nursing, sociology, and health innovation) used a scoping literature review methodology to map a diverse body of literature and explore the range and nature of research activity rather than summarizing best practice (Pham et al., 2014). The review was part of a transdisciplinary doctoral project exploring how design, health, and critical approaches can be integrated and inform participatory practices. Guided by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), an iterative five-stage process was undertaken to 1) identify the research question, 2) identify relevant studies, 3) select studies, 4) chart the data, and finally, 5) collate and summarize the results.

Identifying the Research Question

We initiated an iteration of research questions (RQ) in a pilot search. In parallel, frameworks that could be used to analyze the aspects of concern were identified. The following questions were formulated:

-

What are the general characteristics of health-related research using participatory approaches to involve children or young people in marginalized or vulnerable positions?

-

What are the rationales for involving children or young people in the research?

-

What signifies studies that reach high levels of norm-critical aspects and participation?

Identifying Relevant Studies

The eclecticism of health-related PR was one reason for conducting this scoping review, but also a challenge when choosing search terms and inclusion criteria. The target population was broad – children/young people (generally defined as up to 24 years) – and the tools or methods used could not be labelled in the search since these could be new or customized. The inclusion criteria were thus A) A target population of children or young people, B) In marginalized or vulnerable positions, C) A Health-directed aim (including empowerment related to health issues), and D) Participatory research (PR) or participatory design (PD). Furthermore, articles had to be peer-reviewed, in English, and published after 2010. Searches were conducted Sept-Nov 2022 in Scopus, Cinahl, ACM Digital Library, Pubmed, Psychinfo, and Sociological Abstract. Databases were chosen based on their health or design-related foci. Only empirical material was included while study protocols, dissertations, books, and systematic reviews were excluded. The search string was developed together with librarians. To capture PR where specific tools had been used to facilitate participation and to avoid an unmanageable amount of articles, we omitted the word method due to its comprehensive and diverse meanings in scientific contexts (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Following recommendations from Herriott and Akoglu (2020) we instead used the term tools to distinguish tangible material from general methodologies or methods unrelated to the involvement of the target group. The search was thereby narrowed down to: (children or adolescents or youth or child or teenager or young adult or young people) AND (health or healthcare) AND (participatory research or participatory design) AND tool.

Study Selection

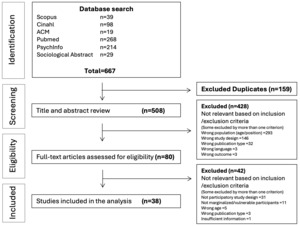

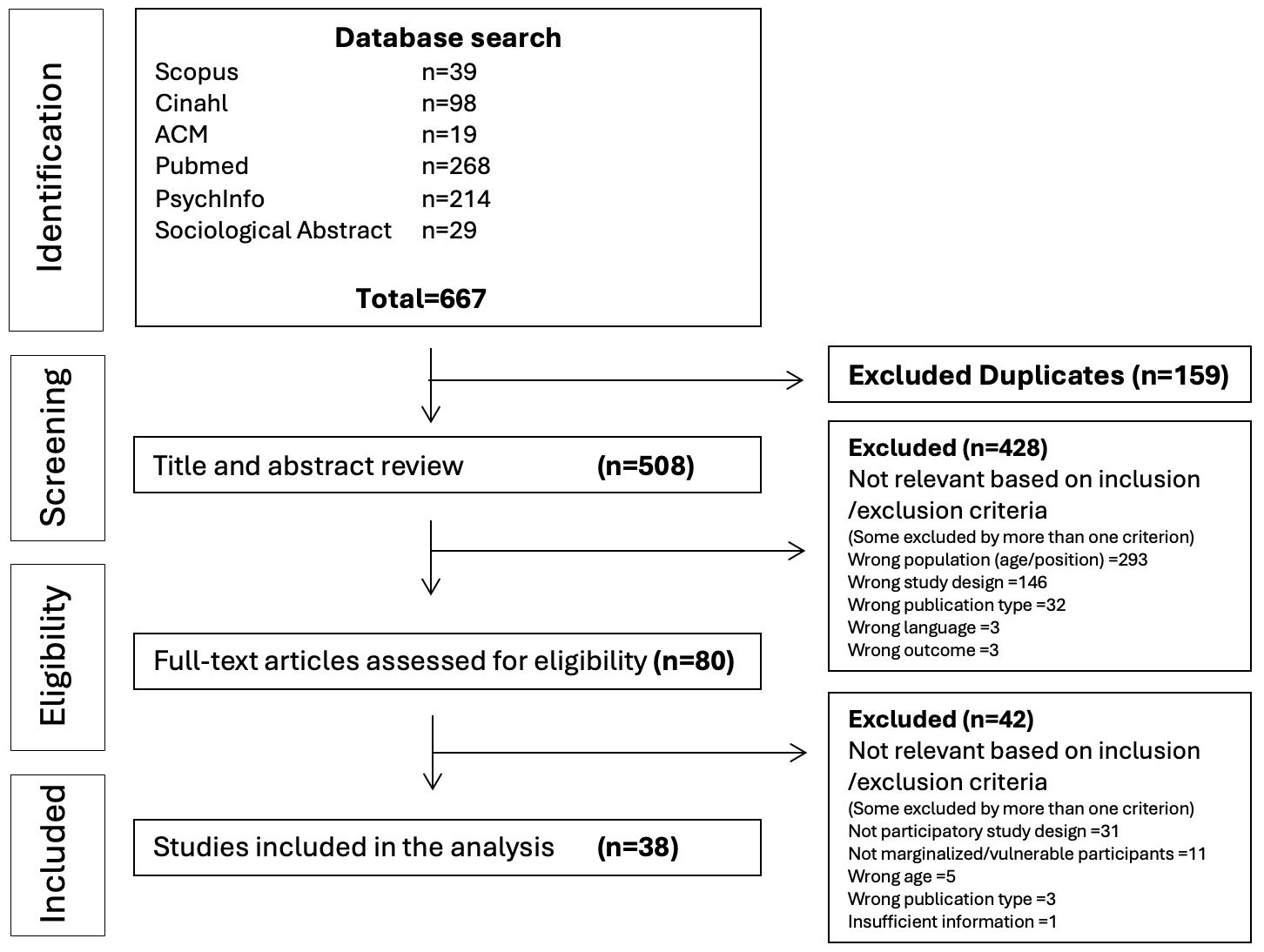

Four researchers screened the results in the inclusion process, where each article was reviewed by a minimum of two researchers. When decisions differed, there was a group discussion until a consensus was reached. Since the scope was broad and participatory is a generously applied term used to label more or less participatory approaches, the screening process aimed to exclude non-participatory research and only include studies where children or young people influenced the knowledge or output produced (i.e. they were not only consulted in phases prior to development/design or testers/validators of what others had developed). Studies were excluded if target groups were minimally involved or if the focus was primarily on adult participants or on group level/community health. If both adults and children were involved (e.g. children and their parents), studies were excluded unless the method, approach, or tool used with children was chosen or adjusted based on their involvement, i.e. adults and children were not participating together or by using adult-centric methods. Studies with mixed participant ages were included if the vast majority were within the age criteria. Populations were seen as vulnerable or in marginalized positions based on authors’ descriptions. These positions could be defined by the local context, such as belonging to an at-risk minority group or having a condition that is stigmatized in one’s community. Children or young people in long-term care or with chronic illness, disease or disabilities were also considered marginalized/vulnerable. Conversely, studies involving broad populations based on age only were excluded, as were studies focusing on school environments where no specific aspects of vulnerability or marginalization were defined. Using the Rayyan software, 508 articles were screened on an abstract level, of which 80 were selected for full-text screening. 40 articles were then deemed eligible and read in full text, resulting in 38 articles included in the analysis. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of this process.

Charting the Data (RQ 1)

Characteristics of the studies were charted in Microsoft Excel. The charting strategy and the resulting data were discussed among all authors. The general characteristics included author(s), year, location(s), target population, age span of children/young people involved in participatory activities (where only school grades were stated we used the typical age for the stated grades in the specific country), journal, discipline (according to Scopus’ categorization of journals), outcome type, study design/method, and tools and materials used to involve the children or young people.

Collating the Results – The Analytical Framework

An analytical framework was developed to address RQ 2-3. The framework’s three parts related to Rationales for involvement (RQ2), Norm-critical aspects (RQ3), and Participation levels (RQ3). Questions were constructed for each part to enable an assessment of the studies (conducted by the first author). The questions were based on existing youth participation frameworks and norm-critical/critical PR and health-related research, as described in further detail below. The analytical framework was tested on four studies by two of the authors, who compared their results and reached a consensus on the scoring criteria before applying it to the full sample.

Analyzing Rationales for Involvement (RQ 2)

This part of the analytical framework served to identify what the authors described as the main value or reason for involving children or young people. This was of interest considering that such epistemological underpinnings might influence how PR is carried out (Hawke et al., 2018). Njelesani and colleagues (2022) found that in PR with children with disabilities, a medical model of disability dominated rationales which meant that developing effective treatments was the main reason for participation and not children’s rights to be included in the knowledge production. While effective treatments are important, the risk with purely ‘results-based’ foci is that the participatory aspect merely becomes a means to an end and that children’s and young people’s perspectives are not researched thoroughly (Stafford, 2017). Hussain argues that the motivation for inclusion is as important as the level of participation, and warns of “uncritically seeking high levels of participation only to justify the project outcome since this yields an instrumental use of children” (2010, p. 112). It is thus important to understand how researchers perceive the value of participation. There has been a mix of rationales for participation in health research, including democratizing science, empowerment, and enhancing the utility of the output (Nielsen & Boenink, 2020).

The democratizing rationale is based on ethical ideals of representation and inclusive research processes that avoid inappropriate, stigmatizing, or judgmental procedures (Clavering & McLaughlin, 2010; Cook & Bergeron, 2019; Thomas, 2017). Extensive participation is often seen as facilitating empowerment (on an individual or group level) in approaches like Community Based PR (CBPR), where social change can be an explicit goal. Participation can thus be both a means and an end, and activities such as member checks can be used to assess the change (Thomas, 2017). The rationale to enhance the utility of the output is instead based on the constructivist logic that both knowledge and solutions are context-based and that users’ tacit knowledge must inform the tools or services they are to use (Spinuzzi, 2005). Yet another rationale for involving target group representatives is their potential to increase the group’s acceptance of the output, such as an intervention or tool (Bird et al., 2019; Monteleone, 2018; Shaw & Nickpour, 2021). Furthermore, engaged and influential participants can help disseminate the output and thereby increase its impact (e.g. social change) (Wright et al., 2018). Rationales may be linked to theoretical perspectives. While norm-critical innovation often is grounded in socio-technical perspectives (Fuenfschilling et al., 2022), theoretical approaches may take different forms depending on the discipline. This part of the analytical framework thus aimed to capture the range of both rationales and theoretical perspectives used in the studies. The following questions were constructed to serve as a foundation for the analysis:

Which of the following was the main rationale for involving children or young people? (Where more than one was mentioned, the most dominant was chosen).

-

Democratizing the research process (Nielsen & Boenink, 2020)

-

Empowering a marginalized group (in a specific context) (Nielsen & Boenink, 2020)

-

Enhancing the utility or acceptance of the output (Monteleone, 2018; Nielsen & Boenink, 2020; Shaw & Nickpour, 2021)

-

Enhancing the impact of the output (Wright et al., 2018)

Was any theoretical framework referred to and if so which one(s)? (Fuenfschilling et al., 2022)

Analyzing Norm-critical Aspects (RQ 3a)

A norm-critical approach is dynamic, rather than a fixed set of knowledge and skills. Previous research has highlighted the importance of using norm critique not only to enhance awareness of norms but also to achieve change, since mere awareness is not sufficient. Rather, active efforts toward norm transformation are necessary (Tengelin, 2019). Taking this into account, the norm-critical framework developed and applied in this study is designed to capture active efforts toward norm transformation. Various existing and emerging frameworks that align with this ambition have therefore informed its development. Fuenfschilling, Paxling, and Perez Vico (2022) pinpoint five characteristics of norm-critical innovation*: identification and disruption of norms, inclusive processes, a socio-technical approach, creation of knowledge-sharing networks,* and engagement in advocacy. These were all included in the framework, although we intended to capture all theoretical variations (not only socio-technical perspectives) in the previous section as described. Furthermore, given the contextual, structural and power-related challenges in health research and design with children and young people in marginalized or vulnerable positions, we considered it relevant to also capture dimensions of reflexivity. In norm-critical pedagogy a core aspect is to shift the focus from the marginalized ‘other’ (the child or young person) towards excluding structures and those in power positions (Kumashiro, 2015). Adult researchers and health professionals represent privileged institutions and are in control of scientific knowledge production and dissemination. Power dynamics between participants, hierarchies between participants and researchers, as well as researchers’ or other stakeholders’ biases and interests, may all be subject to self-reflection.

The final framework contained four main aspects, adjusted to suit the context and the research questions. These were Aim, Tools, Reflexivity and Sustainability, grounded in Fuenfschilling, Paxling, and Perez Vico’s characteristics (except theoretical approaches which was explored in the previous part of the framework) and with the addition of reflexivity. The creation of knowledge-sharing networks and engaging in advocacy were combined under the aspect of Sustainability. As a next step, we developed sub-questions to enable the assessment of each aspect. While the term norm-critical is scarcely used in health-related PR and PD, these fields held some relevant literature which contributed to the questions for each aspect. This related to customized tools and procedures (Nielsen & Boenink, 2020); methods to motivate and enhance children’s power and influence in PR processes (Kinnula & Iivari, 2021); amplifying marginalized voices and challenging dominant narratives (Shaw & Nickpour, 2021); output ownership for participants (Monteleone, 2018), author reflexivity relating to the research process (Kinnula & Iivari, 2021; Mantoura & Potvin, 2013; Monteleone, 2018), and researcher bias (Haraway, 1988; Robinson & Fisher, 2023; Tracy, 2010). Other aspects of these contributions were left out, however, such as the calls for competence development (Kinnula & Iivari, 2021) and empowerment for participants (Monteleone, 2018). While acknowledging that learning new skills can facilitate co-production and may well benefit those involved, such requirements contrast norm-critical perspectives in that they reflect adult-centric views of children and young people as ‘people in the making’ and in need of learning (from adults), rather than as experts in their own right (Nguyen et al., 2021; Stoecklin & Fattore, 2018). Learning criteria would also be at odds with inclusive research principles if there is no equivalent requirement for adult stakeholders to learn communication or co-producing skills (Clavering & McLaughlin, 2010). The following questions for the four aspects, informed by the described contributions, served as the foundation for the norm-critical analysis. Each sub-question generated one point, regardless of its degree or extent. Ticking off all 11 sub-questions would hence give a study a total score of 11 points.

Aim: Which of the following aspects were part of the study aim (long term aims included)?

-

Identify and disrupt norms or structures (Fuenfschilling et al., 2022)

-

Amplify marginalized voices (Shaw & Nickpour, 2021)

-

Challenge dominant societal narratives (Shaw & Nickpour, 2021)

Tools: Which of the following can be said of the tools/materials that were used?

-

They were selected to motivate and suit the target group and context (Fuenfschilling et al., 2022; Kinnula & Iivari, 2021; Shaw & Nickpour, 2021)

-

They were adjusted or customized during the process (Nielsen & Boenink, 2020)

-

They enhanced participants’ power to influence the process, outcome, or impact (Kinnula & Iivari, 2021)

Reflexivity: Which of the following issues do the authors address?

-

Power differences and dynamics within the study setting or between participants (Kinnula & Iivari, 2021; Mantoura & Potvin, 2013; Monteleone, 2018)

-

Bias, political, or social issues within the study and knowledge production (Self-reflexivity) (Haraway, 1988; Monteleone, 2018; Robinson & Fisher, 2023; Tracy, 2010)

Sustainability (change-oriented): Which of the following can be said of the study?

-

Knowledge-sharing networks with powerful stakeholders were created (Fuenfschilling et al., 2022)

-

Advocacy activities took place (Fuenfschilling et al., 2022)

-

Participants could use the research output (Monteleone, 2018)

Analyzing Participation Levels (RQ3b)

The nature and levels of participation in PR with children and young people vary. It is often difficult to distinguish consultative from collaborative participation (Larsson et al., 2018; Montreuil et al., 2021; Sevón et al., 2023), and data translation processes (e.g. from needs to solutions) are often performed by researchers or designers (Iivari et al., 2015; Shaw & Nickpour, 2021). Ladder models that define different levels of child/youth participation have therefore been used to describe participation in research, the most notable being Hart’s Ladder of Participation (Hart, 1992) and the reworked version Shier’s Pathways to Participation (Shier, 2001). These models have been adapted and further developed within specific fields such as health interventions (Larsson et al., 2018) and health related design (Hussain, 2010; Nygren et al., 2017). In the field of social (policy) work, the Lattice of Participation (Larkins et al., 2014) challenges the normative notion of ladder metaphors that high levels of participation always are aspirational regardless of context, and offers instead a comprehensive framework of actions that may be considered to enhance the influence of children and young people. Various models were considered although we had to settle for a more general one as it had to be applicable to the diverse group of studies in this scoping review, where topics ranged from developments of health app and serious games to explorations of food justice, social identity and hospital experiences. A non-complex model was also needed since the analysis would already require some degree of interpretation of what an activity in a particular study would correspond to in a model. The steps of Hart’s established model proved to be the most versatile (a visual model with guiding examples was obtained from the Ministry of Youth Development, New Zealand[1]). Hart’s ladder steps 1-3 exemplify non-participation (Manipulation; Decoration; Tokenism) while steps 4-8 describe levels of actual participation which thus formed the basis for the questions in this part of the framework. However, acknowledging that being further up the ladder is not always better or necessary and that other models may prompt more reflexive project planning, our usage of Hart’s levels simply aimed to get a rough indication of a target group’s influence during a research process as this would help visualize patterns in the group of studies. Furthermore, Todd’s (2012) argument that Hart’s linear conceptualization lacks “the political complexities that shape the production and reception of the child in research” and that research is needed that also considers purpose, methods, and interpretation, strengthens the case for an analytical approach that looks at participation and beyond – as was the intention with our combined framework.

Since studies had to be considered participatory to be eligible for this review (see Study Selection), none were positioned below level 4. The question to serve as a foundation for the analysis regarding participation levels was thus as follows, with scores between 4-8 (corresponding to the model’s levels):

What level of participation does the study have? (Hart, 1992)

-

Initiated by children/young people, with adults as equal partners in share decision-making (Level 8)

-

Children/Young people lead and initiate action with adults’ permission (Level 7)

-

Adult-initiated, shared decisions with children/young people (Level 6)

-

Children/Young people are consulted and informed (Level 5)

-

Children/Young people assigned but informed (Level 4)

Results

Each research question will be addressed in this presentation of the results where the first (descriptive) section presents the studies’ general characteristics (RQ1) and rationales for involvement, including theoretical perspectives (RQ2). The second section adds the dimensions of participation and norm critique to these characteristics, rationales, and perspectives. The third section focuses on the group of studies that gained high scores for both participation levels and norm-critical aspects, as there may be things to learn from their methodologies (RQ3).

1. General Characteristics

This section gives an overview of the studies’ demographics, populations involved, output types and methods, tools and materials, rationales for involvement, and theoretical frameworks.

1.1. Study Selection Overview

The origins of the studies in the sample were dominated by the USA (14 studies), the UK (7 studies), and Canada (6 studies). All studies but one (from Mexico) were performed in high-income countries although some focused on populations in low-income countries (Indonesia, Kenya, Saudi Arabia, Uganda, and Tanzania). The characteristics of the target populations varied, and a substantial number (7 studies) focused on native or indigenous young people in North America and Australia. The most represented discipline was Public Health, Environmental and Occupational Health (7 studies), followed by Rehabilitation (5 studies). Common Journals were Journal of Medical Internet Research (JMIR, including sub-journals) with 5 studies, and Health Promotion Practice with 3 studies. Table 1 presents the authors, country, target population and journal for the studies.

1.2. Ages of Participants Involved

The participants’ age ranged from 2 to 35 years (four studies with participants older than 24 were included as the vast majority of the participants were under 24). Age spans varied, with as much as 16 years between some participants (Study 14). While many studies also involved other stakeholders or “experts”, we focused only on the number and ages of children or young people. To be able to compare these populations, the figure in the middle of the oldest and youngest participant was labelled mid-span age. The proportions of mid-span ages (grouped in intervals) are presented in Figure 2, showing that the most common group were 11-15 year-olds (47%).

1.3. Output Types and Methods

Generally, two types of research output could be identified. The first entailed the development or design of tools, interventions, or care services, leading to the classification of these studies as Development studies (17 studies). The second type of output involved explorations of target group perspectives within specific contexts where the goal was to gain insights (sometimes intended to be used in future development studies) – hence classified as Insights studies (21 studies). For both types, method contribution was frequently stated as an output in addition to the main development or insights, and nearly half of all studies were presented as contributions to (participatory) method development. Studies referred to different participatory methodologies, most commonly Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR). Of the 12 studies using CBPR, 10 were Insights studies. The Development studies more commonly applied arts or design-based methods such as Participatory Design (Table 2).

1.4. Tool Types and Materials

The tools and materials used in the studies varied widely. Tools were also combined and used in different ways. Development studies typically combined more tools than Insights studies. Photovoice was used in 14 studies (the photo technologies varied) and almost as common were drawing or sketching tools. Visual material was used in seven studies in addition to the photovoice studies, which meant that visual material was used in 21 out of 38 studies. Tool types and usage are illustrated in Figure 3. Apart from tangible materials, many used interviews (11 studies) and group discussions/focus groups (14 studies) either during interaction with tools or in separate steps.

No clear pattern was identified when looking at tool types used for different ages. Exceptions were a cluster of video and drama/dance/song/poetry in studies with mid-span ages 14-18, and that Writing was only used in studies with mid-span ages 12-17. Photos/visuals and Photovoice were used throughout the age groups. Appendix I lists all the tools and materials used for different mid-span age groups.

1.5. Rationales and Theoretical Frameworks

All four types of rationales outlined in the analytical framework were reflected in the studies. Enhancing the utility or acceptance of the output was the most applied rationale, reflected in 37% of studies. Empowerment of marginalized group and Democratizing the research process were applied in 26% and 24% of studies, while Increasing the impact of the output was applied in 13% of studies.

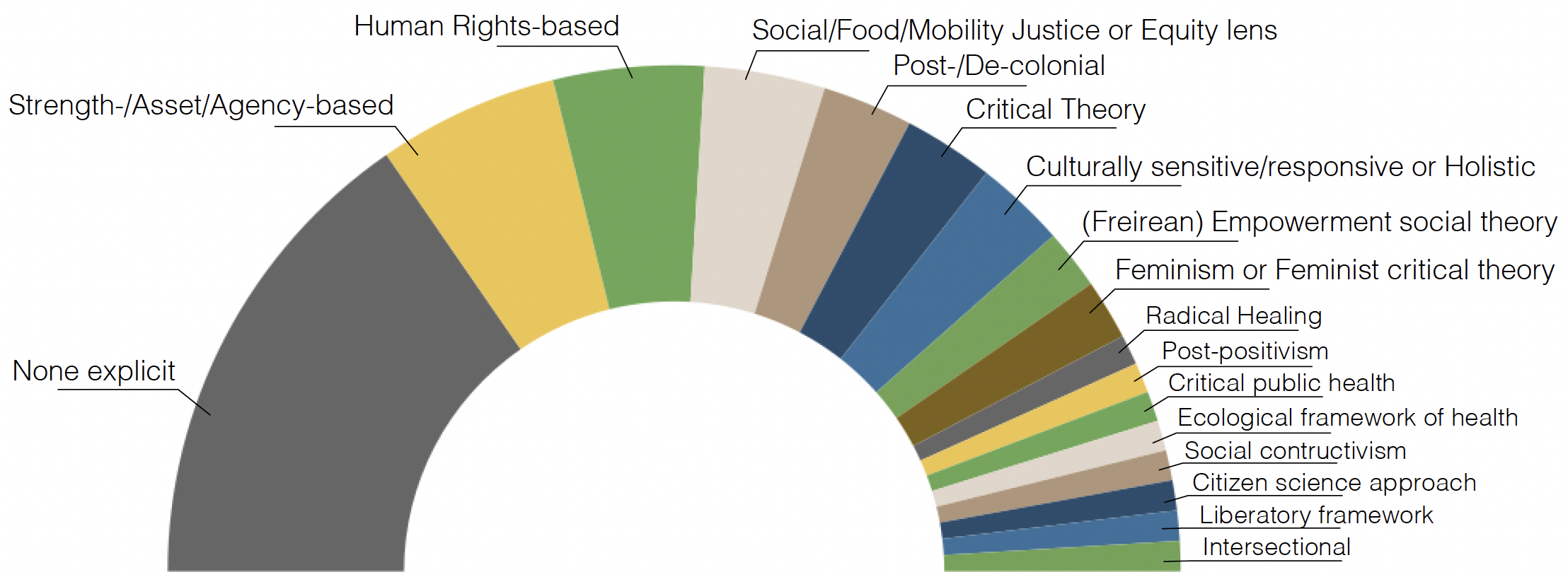

A third (16) of the studies did not mention any specific theory, framework, or theoretical perspective. The ones that did mostly referred to Strength, Asset, or Agency-based (12%), Human Rights-based (10%), various Justice or Equity-based (8%), Post or De-colonial (6%), Critical (6%), and Culturally sensitive/responsive or Holistic (6%) frameworks (we used authors’ labels and grouped similar ones). Ten other frameworks were mentioned in one or two studies only (Figure 4). Only 6 of the 17 Development studies referred to theoretical frameworks (mainly Human rights-based). Meanwhile, 16 of the 21 Insights Studies referred to theoretical frameworks and a great variation was reflected in these (although no Human rights-based).

2. General patterns for Participation Levels and Norm-critical aspects

The analytical framework was partly used as an assessment tool. This section presents general patterns for participation levels and norm-critical aspects, and patterns relating these dimensions to other aspects of the studies.

2.1. Participation Levels and Norm-critical Scores

The average participation level for all studies was 5,4 (maximum 8) on Hart’s Ladder of Participation, and the average norm-critical total score was 6,4 (maximum 11). Despite the developments in participatory methods and the attention brought to child participation by the UNCRC, we could not identify an absolute increase or positive trend in either participation levels or norm-critical scores over the 12-year period. When each study’s participation level was compared to its norm-critical total score, it was clear that most studies with high participation levels also had high norm-critical total scores, and vice versa (Figure 5).

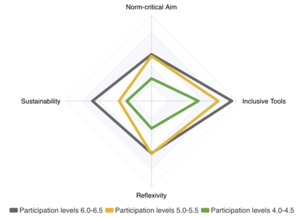

When looking at the four aspects of the norm-critical framework, Inclusive Tools was the one that scored highest across all participation levels. The higher the participation level the higher this score, and studies with the highest participation levels scored on average 94% on Inclusive Tools. The other aspects varied, and studies could for example score zero on Reflexivity or Sustainability and still achieve high levels of participation, as well as high scores on other aspects of the norm-critical framework. Figure 6 shows a fairly symmetrical pattern for the four norm-critical aspects when grouping studies according to participation levels. This could imply that these aspects are somewhat related. Studies with participation levels 5-6.6 had almost equally high scores on Norm-critical Aim and Reflexivity which was substantially higher than the lower-level studies. Another aspect that stood out was Sustainability, which stood for a focus on post-project impact, networking, and advocacy. While noting that not all studies concerned the final phases of a project, we could see that the group with the highest participation levels had a substantially higher score average for Sustainability (69%) than the other groups (which had 38% and 29% respectively) (Figure 6).

2.2. Participation Levels, Norm-critical Scores and Age

Illustrating participation levels according to mid-span ages indicated that participation was generally higher for older populations, although the levels varied as shown in Figure 7 (left). Studies involving 14-27-year-olds had the highest participation level averages. The pattern for norm-critical aspects was even more diverse (Figure 7, right), possibly reflecting that participation is more standardized than norm-critical aspects in participatory research.

2.3. Insights Studies and Development Studies

The average participation level and norm-critical scores differed between studies that developed tools, interventions, or care services, and studies that explored target group perspectives. The Development studies, which often used design-based methods, attained on average both lower participation levels and lower norm-critical total scores compared to the Insights studies, where a majority applied CBPR approaches (Table 2).

2.4. Tools and Materials

While every tool can be used in a more or less participatory fashion, we saw that Writing and Video were used in studies with the highest participation levels and norm-critical scores, while studies using 3D tools or Crafts achieved lower levels and scores. The tool choices sometimes reflected which age groups were involved (see 1.4). Video-making was used in highly participatory processes in the studies within this sample, but for other visual tools the participation levels varied. For instance, photos or images were in some studies generated or chosen by the children or young people themselves while in other studies by researchers (to stimulate discussions or communicate concepts to get participants’ feedback). Furthermore, different tools were often combined, and studies that used a range of tools attained both higher participation levels and norm-critical scores. Photovoice was predominantly used in the Insights studies and its usage did not seem to increase or decrease over the period. The levels of participation varied for the Photovoice studies and as for the full sample (see 2.1) some of the highest norm-critical scores were found in studies where participation levels were also high.

2.5. Rationales and Theoretical Frameworks

The average participation levels and norm-critical scores for each rationale differed slightly. The most common rationale – Enhancing the utility or acceptance of the output – was the one with the lowest average for both participation levels (5,3) and norm-critical scores (5,4). A majority (13 of 17) of the Development studies applied this rationale. Empowerment of marginalized group (the second most reflected rationale) had the highest average score for participation levels (5,7), and the second highest average for norm-critical total scores (7,0). Most of the common theoretical frameworks were used in studies with both low and high participation levels. The more frameworks mentioned in a study, the higher the participation level average. Still, the large group of studies that did not refer to any theoretical framework had a slightly higher average than the group of studies mentioning just one, and six of the zero-framework studies attained 6 or above on Hart’s Ladder. This could potentially be explained by researcher habits of routinely referring to a standard framework, whereas the exclusion or combination of theories might imply that more thought went into a study’s conceptual phase. We also noted that studies referring to common frameworks such as Strength, asset, or agency-based, and Human rights-based more often scored below 6 for participation levels and below 7 for norm-critical aspects. Conversely, Critical and Feminist frameworks were only used in studies that achieved participation levels 6 and above, and Feminist and Post or de-colonial perspectives were only found in studies scoring 7 and above for norm-critical aspects.

3. The high-scoring Studies

11 studies attained participation level 6 and above (where decisions are shared with young people, i.e. level 6 and above on Hart’s ladder) and a norm-critical total score of 7 and above (summarizing all aspects and corresponding to a total score above 60%). Three of these were Development studies (Study 1, 24, 27).( A broad variation was observed apart from this aspect. All four of our framework’s rationales were represented, where Empowerment of marginalized group was the most represented (Study 37, 23, 33, 19). Studies with the highest norm-critical scores typically referred to several theoretical frameworks. The frameworks varied, but a majority (2/2 or 2/3) of the studies that used Critical, Feminist, Culturally sensitive/responsive or Holistic, and Post/De-colonial frameworks were in this group of high-scoring studies. Four studies did not refer to any theoretical framework (Study 10, 19, 24, 27), similar to the proportion of the full sample. However, no Human rights-based framework was present in this group, while this was the most common framework in the lower scoring studies and the second most common framework in the full sample. The mid-span age of the children and young people involved ranged between 14 and 22 years, the youngest participant being 10 (study 24). The average mid-span age was thereby almost two years higher than for the lower scoring group (16,8 compared to 14,6 years). The patterns and varieties in the full sample in terms of tools and materials were also present here. Photovoice and Drawing/Sketching were the most common tool types, and group discussions were frequently used. All but one study that used Writing was in this group. It is also worth highlighting that high-scoring studies often combined tools. Only one study (9%) used just one tool whereas this was the case in 8 (30%) of the lower scoring studies. Table 3 provides details of the tool types and materials, together with the participation level and norm-critical total score for each study.

Discussion

Main Insights

The objective of this scoping review was to explore how norm-critical aspects are reflected in participatory health-related research and design that involve children and young people in marginalized or vulnerable positions, and whether norm-critical approaches can be a way forward to increase participation and facilitate non-tokenistic involvement. We also address and challenge the perceived lack of research tools to involve these groups in health research, by describing the variety of tools and materials used in this PR field. Finally, this review responded to the call for more nuanced frameworks and research approaches that look critically at all aspects of research with children and young people, including purpose, methods, and interpretation (Freire et al., 2022; Todd, 2012). The analytical framework developed for this review enabled us to not only answer the typical scoping questions, but also explore rationales for involvement and signifiers for studies reaching high levels of both participation and norm critique. We found that norm-critical aspects were often present in studies with high participation levels. This means that studies aiming to disrupt norms, offer inclusive tools, demonstrate reflexivity, and strive for sustainable change often achieved high participation levels for the children or young people involved. However, we saw that younger children were less involved in PR than their older peers. Furthermore, studies designing tools, interventions, or care services had lower levels of participation and norm-critical aspects compared to studies that focused on exploring participants’ perspectives. The latter often used rationales of empowerment, and combined theories from critical perspectives rather than human rights or strength-based frameworks. Finally, high-scoring studies offered multiple tools to engage children and young people and leverage their influence throughout the research process and after.

A Critical Mapping of the Field

Many of the studies compiled in this review emphasized the lack of methodologies, detailed method descriptions, and critical method reflections in PR with vulnerable children and young people and saw their respective study as a contribution to an underdeveloped field. We praise this ambition, and our contribution is thus a compilation and mapping of this health-related PR field, and a display of its breadth. However, as such it may also have encouraged and reproduced exclusive practices unless the participatory studies were analyzed from a norm-critical perspective. By turning insights from innovation, health, design, and participatory research methodologies into a framework for assessing norm-critical aspects, we could visualize patterns beyond the general characteristics of studies. This added depth to the scoping methodology and enabled a positioning of what could be called norm-critical PR. Our findings demonstrate that such a framework can generate valuable and applicable knowledge for researchers who strive to increase participation both in research itself and through its output. We discuss below the implications of our findings and raise some methodological considerations.

What Design researchers can learn from Explorative Research

The studies that developed tools, interventions or care services in this review often combined different tools, and design-based research could provide inspiration to other disciplines regarding creative tools for involving children and young people. However, these development studies scored on average lower on the framework for both participation and norm critique compared to studies that explored target group perspectives. While there may be many explanations for this, such a methodological discrepancy is worth attention considering that the output created in development studies may affect many children or young people when implemented in care contexts. Development studies often used design-based participatory methods for the sake of enhancing the utility or acceptance of the output rather than increasing its impact or empowering the target group. They seldom applied theoretical frameworks, least of all critical ones. The larger proportion of the critical, feminist, culturally sensitive, or de-colonial frameworks were instead found in the more explorative studies. Design and health innovation researchers may thus contemplate revisiting their underlying rationales for participation, as well as incorporating theories or approaches used in explorative research to create more inclusive PR (and possibly a more sustainable output). One aspect significant for high-performing studies was the focus on sustainability. Sustainability in PR is often described as essential but complex (Conrad et al., 2015), and dissemination is rarely a funded research phase (Farrer et al., 2015). Change-oriented efforts to sustain impact for the target group through network-building or advocacy might be more established in methods such as PAR or CBPR than in Participatory Design. But considering the difficulties of implementing novel solutions in the healthcare sector, sustainability aspects might be just as relevant in design and health innovation research. Dissemination engagements together with key stakeholders may leverage impact regardless of output type.

Age, Expertise and Influence

Age is just one of many factors that can contribute to a vulnerable or marginalized position, and age does not necessarily correlate with given levels of abilities or preferences. The variation in participation levels suggests that low age need not be a barrier to high participation. Even so, we could see that studies involving younger children seldom reached high participation levels. This is perhaps not surprising given the adult-centered context of research. Many studies mentioned the situated expertise of children and young people but seemed to value this expertise to a varying degree. This was for example visible in acknowledgements and authorships. Perceptions of participants’ potential to contribute might also influence researchers’ choice of tools, whose affordances in turn influence what narratives are conveyed. Considering the unequal resources and power positions of researchers and participants, the responsibility for making processes inclusive always lies with the researchers (Howard et al., 2021). It is also difficult to predict what tools participants will feel comfortable with. Providing alternative tools entails inclusiveness (Freire et al., 2022) and can also inform the process through method feedback (Conrad et al., 2015). Our findings confirm this, as studies with many tool types and where tools were carefully selected, customized, or enhanced participants’ influence reached high participation levels. Hence, while writing was used in studies with high participation levels (and with older participants) it assumes literacy and should be considered as one alternative among others. Some authors described how a combination of tools enriched the understanding. Other authors noted how some experiences are not easily verbalized and thus call for other means of expression (e.g. studies 7 and 33). This adds to the insights brought forward by Dan and colleagues (2019) regarding the affordances of art-based tools in terms of self-expression and effective yet non-exposing communication. Addressing inequalities in resources through accessible and creative tools that participants can identify with is key to mitigate power differentials and leverage the influence of children and young people in research (Conrad et al., 2015). Moreover (as noted in Study 38), such tools do not have to be costly or complicated.

Method Reflections and Limitations

This review involved both descriptive, interpretive, and assessing elements, all of which occasionally proved difficult. The reviewed papers’ different foci constituted a certain unfairness when comparing methodological reflections with papers focusing on project results. We also realize that authors may be restricted by word limits and therefore exclude reflexive arguments. Aims and rationales were sometimes difficult to narrow down since PR has many benefits and studies often had parallel aims. Individual empowerment, community benefits, richer knowledge-production, and acceptance by the target group could be present all at once. Furthermore, participation levels were seldom explicit but subject to interpretation, and sometimes our judgements were not aligned with the authors’. Other times, the assessment was tricky as levels shifted between project phases or even between participants (e.g. study 10). We took note of the higher level in these instances (barriers to participation may originate in unequal access to resources, which may be explored through comprehensive models such as the Lattice of Participation (Larkins et al., 2014)). There exists a certain overlap in the two parts of the framework, given that some norm-critical aspects relate to facilitating participation, especially that of inclusive tools. This potentially explains the pattern symmetry regarding this aspect (as seen in Figure 6). The notion of power is also present in both parts of the framework, but while participation levels relate to exercised power, influence, and participants’ role in decision-making, the norm-critical part aims to highlight researchers’ intentions related to disrupting norms or power asymmetries. While several researchers were engaged in creating the analytical framework, few were involved in applying it. That the first author participated in the entire assessment can be seen as increasing bias, but also meant that all aspects were assessed similarly. The exact scores for each study are however secondary to our aim of highlighting patterns in the field. Finally, while this scoping review excluded non PR-studies, such research could still contain fruitful tools for involving children and young people. Similarly, our focus on health-related research inevitably excluded tools from other design fields which might hold great potential for both health-related and norm-critical research. Nevertheless, collating the variety of methods, tools and materials that have been used in participatory health-related research from different fields can hopefully inspire researchers to involve children and young people in vulnerable or marginalized positions despite the complexity such involvement entails.

Acknowledgements

We thank senior lecturer Mikael Ahlberg, Halmstad University, for assisting with the screening process

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by Halmstad University.

.png)

.png)

_and_participation_levels_(x).png)

_and_norm-critical_scores_(right)_in_relation_to_mid-span_ages_.png)

.png)

.png)

_and_participation_levels_(x).png)

_and_norm-critical_scores_(right)_in_relation_to_mid-span_ages_.png)