Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, young people faced new challenges, such as isolation and quick shifts to online learning, that negatively impacted their mental wellbeing (Panchal et al., 2023). Despite their lived experiences with these challenges, youth were not involved in identifying solutions (Ambresin et al., 2021). It is critical to consider how young people can have spaces to both process these experiences and identify supports. Youth participatory action research (YPAR) is a youth-adult partnered approach to inquiry in which young people identify an issue important to them, conduct research on it, and disseminate the findings to stakeholders who hold power to make meaningful systems change (Ozer, 2017). A key process promoted via YPAR is critical consciousness development, which involves critical reflection, motivation, and action around inequities that marginalized youth and communities experience (Rodríguez & Brown, 2009). Despite the potential emotional toll of discussions about systemic oppression and marginalization, less attention has been paid to integrating wellbeing support for youth throughout the YPAR process.

The current paper explores how blackout poetry in YPAR can support wellbeing by helping youth process emotions, challenge adultism, and share their experiences. We ground our discussion in a case example from a virtual YPAR project, the National Young Adult Wellbeing Network, where young people used blackout poetry to process emotions and reclaim narratives of their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic (Abraczinskas et al., 2023). First, we describe relevant literature to highlight the benefits of integrating blackout poetry in YPAR. Then, we provide a how-to description of our process of using blackout poetry. Finally, we include examples of the blackout poetry young people created and describe them in the context of emotional processing and challenging adultism.

YPAR, Critical Consciousness, and Wellbeing

YPAR is one approach to youth engagement that can support youth development. When identities are explicitly centered, and power overtly discussed, YPAR may be explicitly connected to Social Justice Youth Development. A central tenet of Social Justice Youth Development is that youth actively “contest, challenge, respond to, and negotiate the use and misuse of power in their lives” (Ginwright & Cammarota, 2002, p. 35). During the YPAR critical reflection process, young people examine systemic inequities related to the problem they have identified and how these affect their lives. The reflective process is meant to foster critical consciousness—a key YPAR process and outcome—by increasing awareness of inequities, building efficacy, and encouraging action to challenge unjust systems (Anyon et al., 2018; Diemer et al., 2016). Critical consciousness has been linked to increased empowerment, agency, and positive mental health benefits for young people (Chan, 2024; Diemer et al., 2016; Maker Castro et al., 2022).

Despite these benefits, the process of learning about and working to challenge inequities in systems that may seem intractable and unresponsive can be emotionally taxing, particularly for young people who are most impacted by the inequities (P. Ballard & Ozer, 2016; Maker Castro et al., 2022). For example, Chan (2024) found co-occurring positive and negative effects of critical consciousness on mental health. Critical consciousness was associated with increased levels of emotional distress, highlighting the need to balance critical consciousness with self-care and supporting wellbeing. However, few YPAR studies have focused on how to build wellbeing supports into the YPAR process (Abraczinskas et al., 2023). In this paper we propose blackout poetry as a way to build in wellbeing support during the critical reflection stage.

YPAR scholars have recently called for the integration of social-emotional learning and mental health support strategies in YPAR, especially for minoritized groups (Abraczinskas et al., 2022; Ozer et al., 2021). In a systematic review, Nash et al. (2024) integrated sociopolitical development and transformative socio-emotional learning in YPAR and called for multi-level supports, from meaningful action at the systems level to social and emotional supports at the individual and group level. However, most resources designed to guide YPAR projects focus on the research and action process, without additional resources focused on supporting wellbeing (Erbstein et al., 2020; UC Berkeley, 2024). The current work fills this gap by providing an arts-based strategy (blackout poetry) to support wellbeing during YPAR through emotional processing, which we define as a process of identifying, exploring, and making sense of emotions (Greenberg, 2010).

YPAR and Arts-Based Methods

Incorporating arts activities into YPAR can be both empowering and accessible, by providing opportunities for young people to tell their own stories rather than having an adult researcher tell and interpret the story for them. It can have benefits for youth wellbeing, as creating art can be a way to explore, process, and express complex emotions that often arise when discussing systemic injustices, a key component of the critical reflection phase (Rodriguez et al., 2023). Art has been utilized in YPAR to create new knowledge, represent findings, and positively impact youth wellbeing and healing (Goessling, 2020). YPAR researchers have most frequently relied on photovoice, where youth take and then caption photos that illustrate issues impacting their lives which they then use to advocate for systems change (Fountain et al., 2021; Sutton-Brown, 2014), but other projects have utilized poetry (Cammarota & Romero, 2009), theater (Fox, 2020; Wright, 2020), digital storytelling (Jimenez et al., 2022), and even multiple art methods (Lee et al., 2020). Engaging with art, even in the absence of research, is linked to wellbeing (Rodriguez et al., 2023). Creating art can be cathartic, allowing youth to process their experiences and imagine new opportunities (Goessling, 2020; Wright, 2020).

In YPAR projects utilizing arts-based methods, youth have reported more hopefulness (Lee et al., 2020), healing (Goessling, 2020), and transformative experiences (P. J. Ballard et al., 2023). Art and activism have also long been connected, as creativity can provide a way to imagine a better world and possibilities for social change (Domínguez & Cammarota, 2022). However, while arts-based methods in YPAR can be a powerful way for youth to express themselves and take action, the extent to which voices are heard and valued is influenced by the ways that adults perceive youth.

Adultism

Young people in the United States, particularly young people of color, are more politically and civically engaged than ever before (Serriere & Riley, 2024). However, societal norms often dismiss the lived experiences and work of young people (Bettencourt, 2020; Kennedy et al., 2021), as they are often viewed as problems to be fixed, merely recipients of knowledge and actions, while adults are more likely to be considered credible and capable of taking action (Bettencourt, 2020). However, it is not as simple as youth being viewed as powerless versus adults being viewed as powerful. Age intersects with other identity characteristics, including race, class, dis/ability, gender, sexuality, and other identities, to impact who is considered credible and capable in our society. Not all adults have the same privileges, and not all youth are viewed the same way.

Adults’ perceptions of youth matter because adults are the ones who make many of the decisions that govern youth’s lives (Kennedy et al., 2021). Adultism describes how adults’ perceptions of youth as incapable are codified and reinforced by political, social, and cultural institutions, especially in the United States, as youth are often excluded from power and decision-making (DeJong & Love, 2016; Flasher, 1978; Kennedy et al., 2021). Adultism justifies dismissing youth’s experience and expertise, so institutions designed to serve youth, including schools and youth organizations, rarely include youth voices (Bettencourt, 2020). Importantly, adultism intersects with other forms of oppression and systemic bias to shape how youth are perceived and treated. For example, prior research found that a nationally representative sample of White professionals who work with youth disproportionately associated negative stereotypes, like lazy, unintelligent, and violent, with Black and Latine adolescents compared to their White peers (Priest et al., 2018; Wray-Lake et al., 2025).

Although adultism is often associated with children and adolescents, it also shapes the experience of emerging adults, including the 19–23-year-olds participating in this YPAR project. While legally considered “adults”, emerging adults are still subjected to stereotypes that dismiss their experience and expertise. They must navigate the contradiction of being expected to take on adult responsibilities while experiencing skepticism as capable decision-makers. For example, prior research has found more negative bias towards young adults in leadership positions compared to middle-aged and older adults in leadership positions (Daldrop et al., 2023; Kunze & Menges, 2017).

Adultism towards young adults was especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, the context in which this project took place. During this time, many young adults worked tirelessly to help their communities, including through advocacy, protesting, volunteering, and other forms of civic engagement (Quiles et al., 2023; Yazdani et al., 2022); however, adultism was prevalent in the dominant narrative that portrayed them as victims and/or blamed them for the failure to contain COVID-19. For example, top authorities, including officials at CDC, warned that young adults were driving the spread of the virus (Leidman et al., 2021; Oster et al., 2020), while pictures and videos of crowded beaches, bars, and parties portrayed a generation of young adults who were irresponsible, reckless, and unconcerned about the pandemic. Simultaneously, much research, media, and conversation portrayed youth as victims by highlighting the dire consequences of the pandemic to young people, including mental health issues (Panchal et al., 2023), missed milestones (Mucci et al., 2024), decreased academic achievements (Di Pietro, 2023), and physical health issues (Do et al., 2022). Overall, much discourse during COVID-19 revolved around youth, but youth were rarely included in or leading these discussions (Ambresin et al., 2021). YPAR can disrupt adultism and traditional power dynamics between adults and youth by situating youth as experts and leaders, putting youth with lived experience of inequities at the forefront of finding solutions to systemic problems (Anderson et al., 2021). Blackout poetry can be a powerful tool for countering adultism within the context of YPAR, offering a creative medium where youth can take control of their stories and challenge adult-driven narratives about them.

Blackout Poetry

Blackout poetry is a process that can be integrated into YPAR to promote wellbeing via emotional processing and to combat adultism through young people reclaiming their stories. In blackout poetry, poets create a new poem by selecting a few words from a pre-existing text and blacking out the rest (Ramser, 2020). As a relatively accessible form of poetry, its popularity continues to grow. A quick Google search reveals thousands of how-to guides for blackout poetry, and, as of July 2024, there are over 213,000 posts on Instagram labeled with the hashtag “#blackoutpoetry”. Search results show blackout poetry being used in many contexts, from published anthologies to middle school classrooms to poetry contests for the New York Times.

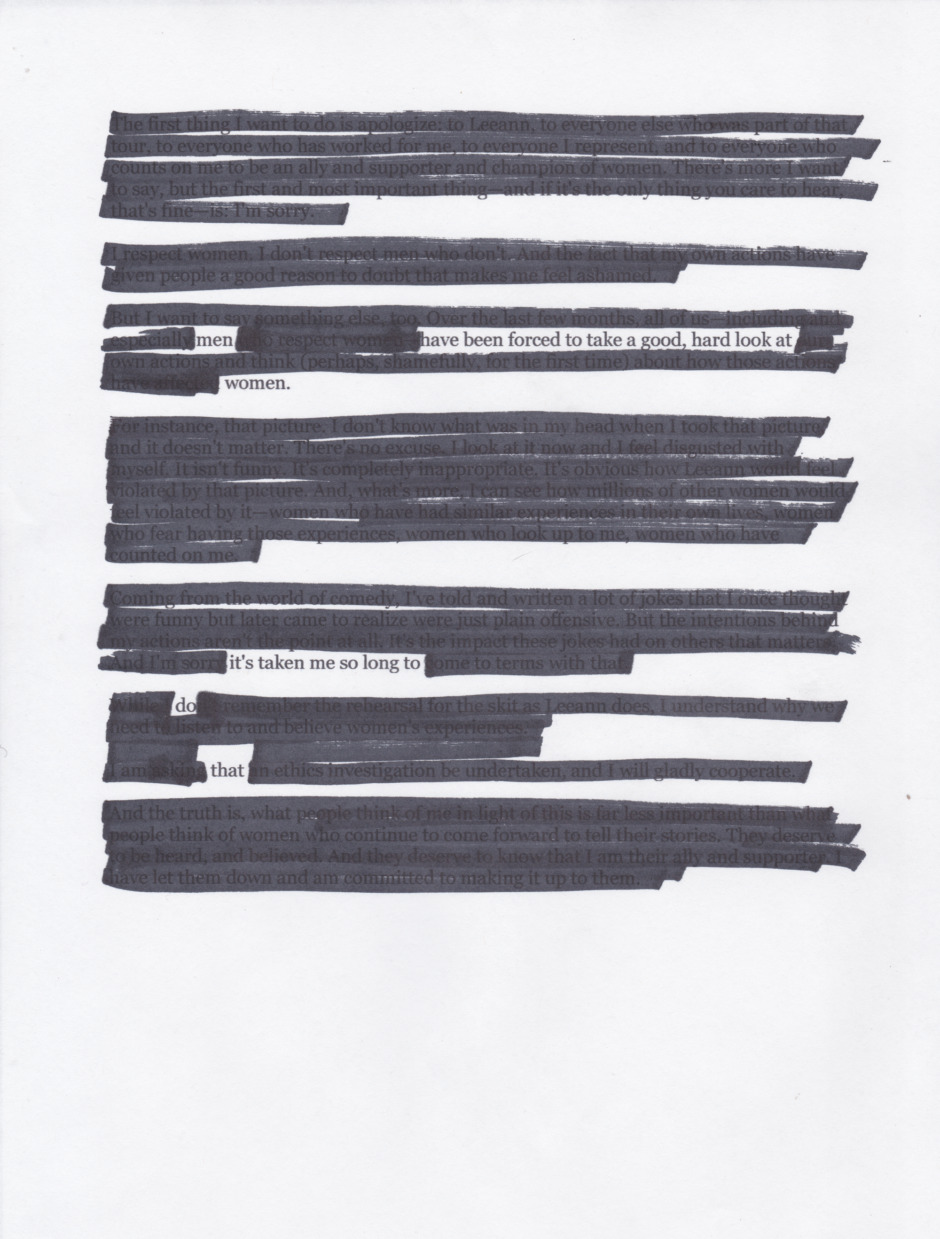

Blackout poetry has long been used as a way for marginalized groups to take back power. One blackout poetry guide describes the artform as inherently empowering, stating “With blackout poetry, the point is to literally take the words from someone else and transform them into what you want them to say. It’s a form of taking back power. You choose the words, the meaning, the end result. It’s liberating and empowering to take back control, even in a small way” (Eby, 2024). As an example, during the peak of the #MeToo movement, Isobel O’Hare crafted a book of blackout poems from the “apology” statements issued by sexual abusers (to read one of these poems, see Figure 1). O’Hare created the poems out of frustration at how the “apologies” all lacked substance and felt nearly identical, saying, “I found myself overwhelmed with emotion by both the accounts of victims (#MeToo) and the statements/apologies by the perpetrators. I printed out those statements and sat down with a Sharpie to reveal what I felt they were really saying about themselves, their privilege, and their willful oblivion to the consequences of their actions.” In her poem “so long to do that”, O’Hare changes an “apology” into a statement that reveals men’s ignorance about the experience of women (Ramser, 2020).

Although there are many descriptions of blackout poetry generally, prior work has not detailed how blackout poetry can be used in YPAR to aid in emotional processing and combat adultism, especially because there is a dearth of literature on wellbeing supports in YPAR. Further, because most YPAR literature focuses on outcomes, process evaluation, or the overarching project (Anyon et al., 2018; Kennedy et al., 2019; Shamrova & Cummings, 2017), there is less literature focused on practical guidance in general. A notable exception is Kohfeldt and Langhout’s (2012) article about the Five Whys Method, which has been cited nearly seventy times since its publication in 2012. Although the Five Whys Method focuses on critical consciousness development, rather than promoting wellbeing, it points to the need to provide rich descriptions of flexible processes that can be used in YPAR for other scholars and practitioners to replicate and adapt.

Overarching Project

This article draws from a broader project evaluating the National Young Adult Wellbeing Network, a virtual YPAR network that utilized art to understand fifteen young people’s needs for wellbeing and healing in the wake of the pandemic and ongoing racial injustices. Participants aged 19-23 were recruited from California, Florida, and Colorado. These states were selected because of the geographic location of the project leads. The project was funded by the Life Course Intervention Research Network, with the intention of bringing together a group of young adults to 1) inform decisions about funding and future research for both the Life Course Intervention Research Network and other organizations and 2) inform a grant application for a larger trial of a YPAR intervention and its impact on wellbeing.

Two professors (the third and fourth authors) and one graduate student (the first author) worked together to create sequenced activities for the Young Adult Wellbeing Network curriculum. Over the course of eight 90-minute Zoom meetings, young adults analyzed and created artwork about wellbeing and the impact of COVID-19 and racial injustice and began action planning about solutions and next steps. Table 1 shows an overview of activities–the blackout poetry activity was the second session. Before jumping into blackout poetry, our first session allowed everyone to get to know each other, create group norms, and define objectives. In the first session, young people also chose art supplies and snack boxes, which we then mailed to everybody. We used three distinct art forms as inquiry into youth’s lived experiences (sessions 2-4). For more information about the overarching project, see Abraczinskas et al., 2023.

Table 2 shows young adult demographic information by state. We recruited via emails and fliers distributed to the second, third, and fourth authors’ existing networks, targeting youth who worked with them on other research projects, youth leadership boards, or social justice groups. We originally planned to recruit only racially minoritized youth, but due to a truncated recruitment period due to IRB delays, we recruited a racially mixed group. Additionally, most participants identified as female.

The racial diversity of our group, both the young adults and adult facilitators, influenced the project. Related to the three adult facilitators, the fourth author identifies as a Mexican American immigrant, first-generation college student, cisgender man, and the first and third authors identify as White, cisgender women. The second author also identifies as a White, cisgender woman, and co-led the grant writing and helped with planning, project design, and analysis. These identities impacted the way we as facilitators were able to build trust and navigate discussions on race and power. The fourth author’s background helped him build trust and connection with participants who also identified as Mexican American or first-generation, while the White facilitators tried to be intentional about modeling conversations about Whiteness and White supremacy culture and being mindful of the space they took up in discussions. Conversations in the group built from trust and relationships with these young people who were prior participants in other social justice-oriented groups led by facilitators years prior to the pandemic.

Because our group was racially diverse, we took steps to facilitate productive intergroup contact. Even during our initial interest discussions, we asked young people about their comfort level and experiences with discussing race and racism. At the end of the project, young people expressed that the Network created a strong sense of community, and they appreciated opportunities to connect with peers with both similar and different backgrounds, racial and cultural identities, and lived experiences (see Abraczinskas et al., 2023 for more details). However, our group composition also presented challenges. Although our group was racially mixed, most young people were Latine (n=7) or White (n=5), with only three young people identifying as Black. One Black participant shared that Black voices felt underrepresented in our discussions, given the focus on racial justice. This underrepresentation was amplified because White and Latine participants were spread across all three states, whereas all Black participants were from Florida. As a result, Black participants did not have the opportunity to compare their experiences with Black youth from other states (Abraczinskas et al., 2023).

Blackout Poetry Process

The following section outlines the six steps for our blackout poetry process: 0) create a safe/brave space with a strong foundation of trust/rapport, 1) choose source material and frame the process, 2) provide examples and engage in shared vulnerability, 3) provide guiding questions, 4) time to create and flexibility in approach, 5) group discussion, and 6) analyze art and develop recommendations. The extent to which each step is youth-led can vary depending on your specific YPAR project. In our project, while the adult researchers selected the article and topic, young people took the lead in interpreting, discussing, and analyzing their poetry; identifying key themes; and beginning to develop recommendations based on their collective reflections.

Step 0: Create a safe/brave space with a strong foundation of trust.

Intention: Foster a supportive and inclusive space where youth are invited to be vulnerable and authentic.

Rationale: Sharing art is powerfully vulnerable. Therefore, it is important that, before any expectation of sharing begins, that you create a safe and brave space within the group. By establishing this trust, participants can feel safe creating and sharing their art, especially around challenging topics, without being judged. However, vulnerability should never be required, and any prompts or expectations for sharing should align with the level of trust built in the space.

Process:

-

Co-create group agreements: At the start, we co-created, and revisited weekly, group agreements by asking youth “what group agreements do we need to show up fully in this space?” We specifically asked the young people to reflect on what we as facilitators should do to ensure the group can engage fully, and then we asked, “what agreements are needed for all participants?”

-

Build community: Before jumping into each session, we would typically begin with a check-in question or opening activity to see how everyone is doing and build connection. We also co-created a group playlist of “pump up” songs that were played every time we went into the quiet art-creation moments.

-

Engage in shared vulnerability: As facilitators, we participated in activities, including creating blackout poetry. Creating and sharing art and experiences is a vulnerable process, and we felt it was important to not ask young people to be vulnerable in ways that we as facilitators were not willing to do. In post-interviews, several young people appreciated this dynamic, with one saying “it felt pretty equal that it wasn’t just, okay, we’re the adults, and you’re all going to share your feelings, and we’re going to listen. And it’s like no…we’re going to participate with you. It’s not just we’re standing here pointing and guiding you…We’re by your side” (Moriah, State 2).

Step 1: Choose Source Material and Frame the Process

Intention: Select source material young people will work with that aligns with project goals and introduce youth to the purpose of blackout poetry. Alternatively, you can identify a few options from which youth can select.

Rationale: It is important to carefully select and frame the source material so that youth can meaningfully engage with blackout poetry. It may be important to consider the source material and how it aligns with the larger YPAR project.

Process:

-

Identify goals for the activity: The source material you choose depends on the purpose of the blackout poetry activity. Is the purpose of creating the poems to serve as a counter narrative to adult-dominant framing of an issue? Is the purpose a way to educate youth on an issue and encourage them to create a personal story out of facts? For example, in our project we invited young people to use their lived experience to challenge dominant, adult-driven narratives in the media of youths’ perspectives and actions during COVID-19.

-

Select source material: There are many options for source material! Do you want to use an article, factsheet, government document, application form, or music lyrics? Consider the reading level of your audience and the length of time you have for creating poems. Longer source material can be excerpted, or youth can select one or more pages to work from. Think about what would work best for your group. Youth can also be involved in the selection of source material. In our project, we started with source material that described young people’s experiences during the pandemic from an adult perspective so that young people could then create new art that highlighted their perspectives and lived experience. We chose an Atlantic article titled “Gen Z is Done with the Pandemic” (Khazan, 2021) that describes how, despite concerns about new variants of COVID-19, young people were not complying with public health guidance. This article echoed dominant, blaming narratives of Gen Z and COVID-19 in the media at the time.

-

Discuss the topic: Before creating blackout poetry, introduce the topic through discussion to explore lived experiences. This process primes youth to draw from those experiences in their art. In our project, we started by discussing our group’s experiences during the pandemic. This set the stage for young people to reflect on their own narratives and lived experiences.

Step 2: Provide Examples and Engage in Shared Vulnerability

Intention: Build young people’s understanding of and confidence with the blackout poetry process by providing examples.

Rationale: Providing a wide array of examples, including examples from facilitators, ensures that youth feel open to create, but have a sense of what the end product might look like. We engaged in shared vulnerability by including our own examples as facilitators.

Process:

-

Check familiarity with blackout poetry: First, we asked the young people about their familiarity with blackout poetry. Most young adults participating in the project had no prior experience with blackout poetry, so it was important to describe the process and provide examples. If you are working with a group of young people who are already familiar with blackout poetry, you might not need to spend as much time describing the process and providing examples.

-

Provide examples from other contexts and describe the process: Next, we shared about the purpose of blackout poetry and showed a few examples from other non-YPAR contexts.

-

Share facilitator examples: In addition to the examples we found online, each of the three adult facilitators created our own blackout poems about our experiences during COVID-19 that we also shared (see Appendix A in Supplementary Material). Even if the young people you are working with have previously created blackout poetry, sharing facilitator examples is still important to create a space of mutual vulnerability.

Step 3: Provide Guiding Questions

Intention: Share questions to frame the activity within its broader purpose.

Rationale: Guiding questions scaffold the process by encouraging youth to deeply reflect on dimensions of their experiences and how they relate to the source material while creating their art.

Process:

-

Introduce questions: Share reflection questions that are aligned with the project’s goals. In our project, we wanted to frame the activity within its broader purpose of processing emotions and highlighting youths’ lived experience during COVID-19. Some groups might need more scaffolding than others, so the questions can be more or less open-ended depending on the needs of the group. Questions should be designed for young people to reflect on their personal experiences and how they relate to the source material. In our example, we asked our group to consider their own experiences of the last year, specifically reflecting on three questions:

-

What choices were made for you? (adultism)

-

What choices did you make to protect others? (counternarrative)

-

How did these changes impact you? (emotional processing)

These questions were chosen to explore experiences that may run counter to the dominant narratives that were communicated in news media and national leadership during COVID-19. We encouraged young people to think about their responses to these questions as they read through the article and began selecting words for their blackout poems.

-

Step 4: Time to Create and Flexibility in Approach

Intention: Give participants the time and space to create their own blackout poem. Communicate that they can use material electronically, use separate paper to construct a poem separate from any digital copy, or any other form of creation.

Rationale: Youth need time to produce something that they would feel comfortable sharing. Participants may wish to produce something digitally or on paper and integrate images to represent ideas or breakup text.

Process:

-

Set the scene: After reading the article, everyone spent the next 30 minutes creating a blackout poem from the Atlantic article. Because we were on Zoom, we emailed the article and had a Google Document for youth to copy. We invited everyone to pay attention to the words that stood out to them. We played our group-created Spotify playlist during creation time to set the virtual space.

-

Support creativity and flexibility: Beyond the guiding questions, we kept the art creation fairly open-ended to promote creativity and allowed young people to design art that reflects their experiences. Our group created a wide variety of poems. Some young people used the whole article, while others used only part. Some created their poems on the computer, while others used pen and paper. Many young people also chose to add illustrations and images. It is important to emphasize that there is no right or wrong way to create blackout poetry–this is their art and their lived experience.

Step 5: Group Discussion

Intention: Have a discussion where young people are invited to share, interpret, and connect through their art.

Rationale: Creating art is just one part of knowledge generation. To explore the meaning of the poems in a collective sense, discussion and reflection are critical. Discussion questions should encourage affirmations for those who shared, in addition to seeking commonalities or distinctions within the art. Finally, reflection can include an opportunity for everyone to reflect on the art creation process generally, or dive deeper into the topic than in the prior opening discussion.

Process:

-

Small group sharing: We reconvened into three small groups to share our poems and experiences for the rest of the session, with one facilitator in each group. Each person had an opportunity to share their poem, the thought process behind it, and how they felt about the experience.

-

Provide discussion questions: Each small group was given the following prompts for discussion; however, the discussion became largely free flowing:

-

When you are listening to someone read what they created, what words drew you in? What visuals did they create in their work?

-

What similarities or differences did you see in the artwork?

-

How was what you created similar to or different from the article?

The first two questions were meant to deepen their understanding of each other’s work and build connections across their blackout poems and lived experiences. The last question was meant to highlight how their stories were often different from the dominant media perspective of youth as a homogenous group with little regard for the seriousness of the pandemic.

-

Step 6: Analyze Art and Develop Recommendations

Intention: Young people can analyze their blackout poetry to generate new insights and recommendations.

Rationale: In our overarching YPAR project (see Abraczinskas et al., 2023 for more details), our goal was for youth to use art as inquiry, analyze the art and identify recommendations, and then share recommendations for impact. The art served as both a form of expression and a data source, which youth could then analyze to develop recommendations for post-pandemic healing and racial justice. Although this paper focuses on the process of creating and discussing blackout poetry, we briefly describe our analysis process below to emphasize the participatory nature of this method by showcasing how blackout poetry was built into our larger YPAR project. In our project, youth created three art products, including blackout poetry, and analyzed all three together. However, a similar process could be used to analyze just blackout poetry.

Process:

-

Reflect on positionality: To begin the analysis, youth reflected on their own positionality, considering their identities, where they are in life, and their core views on issues. They also participated in a brief exercise to illustrate how our positionality shapes our interpretation, which we discussed in the context of what it means for data analysis.

-

Introduce a framework for analysis: Providing a framework can be a way to scaffold and frame the analyses. For our project, we situated analysis within a socio-ecological model so that youth could consider themselves and their experiences in a broader context, but other frameworks or analysis strategies can also be used.

-

Individual analysis: After learning about the socio-ecological model, youth independently reviewed their art to examine how it reflected themes within levels of the model. They used a blank socio-ecological model to record their reflections on the following (see Appendix B for a completed example):

-

Individual – Identity, Skills, Values, Personality: What does your art reflect about your individual self? (e.g., identity, skills, personality, values, goals, dreams, needs, struggles, achievements, hopes)

-

Microsystem – Family, School, Work, Community: How does your art reflect your relationships and experiences with family, teachers, peers/friends, co-workers, supervisors, neighbors, or others in your communities (the communities that matter to you)?

-

Macrosystem – Laws, Policies, Society, Globally: How does your art reflect your experiences with or views about the macro-level contexts – such as laws, ethics, policies (e.g., healthcare, educational, immigration), societal issues (e.g., structural racism, sexism, homophobia, anti-immigrant sentiments)?

-

-

Small group analysis: Then, youth worked in small groups to collectively explore themes from their art and develop recommendations for supporting youth wellbeing. Youth reviewed each of their art forms, and reflected with their groupmates on the following questions:

-

What themes are popping up for you in your art? What are you learning? New thoughts you are having from thinking more deeply about your art?

- Find themes for each of your art forms and across your different art forms.

-

Thinking ‘Socio-ecologically’, what does your art say about the different levels? Or what themes are related to particular levels (e.g., identities, family, school, community, society)

-

Remember our focus on COVID-19, social justice, and emotional well-being – what is being revealed in your art about these topics?

-

Based on your themes, what recommendations for supporting well-being would you offer?

-

-

Full group discussion: Afterwards, we came together to share what youth came up with and explore core themes across everyone’s art, paying attention to shared patterns, lessons learned, and visions for the future, to think about what actions should be taken based on our themes.

Blackout Poetry Illustrations of Youth Experiences During COVID-19

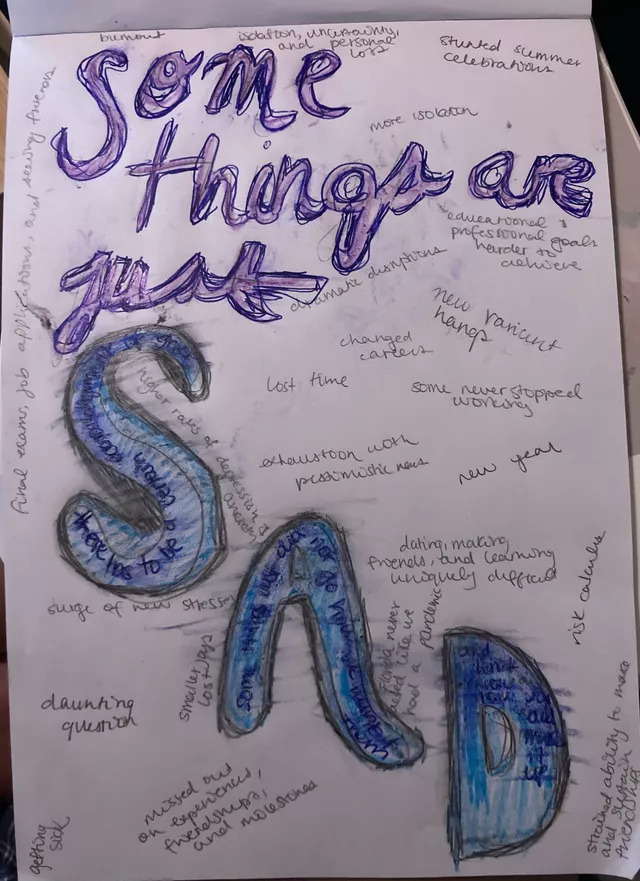

Here, we feature the work of two young adults: Eloisa from California and Penny Lane from Florida (names are pseudonyms). By creating their own art from an article describing how Gen Z acted during the pandemic, young people were able to process their emotions while emphasizing their own perspectives and lived experiences.

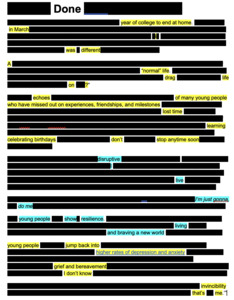

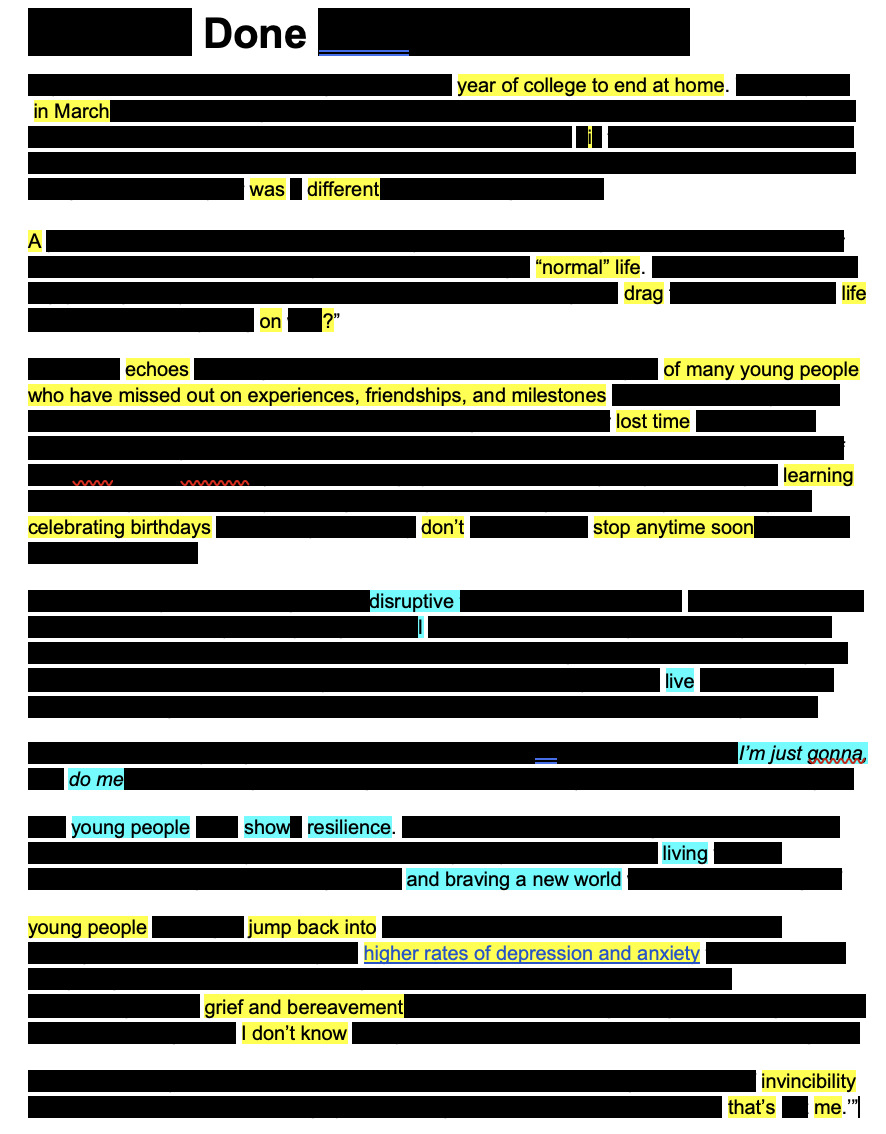

Example 1: Challenging Deficit Narratives

Eloisa used her blackout poetry to both process painful experiences and show her resilience. Her poem highlighted much of the pain of living through a lingering pandemic, beginning with her title: “Done”. In fact, several other young people titled their art the same way, illustrating shared feelings of exhaustion and frustration. Eloisa’s poem provides space to process the losses and challenges she experienced, including grief, missed experiences, mental health challenges, and the uncertainty of the pandemic. At the same time, she chose to include how “young people show resilience, living and braving a new world”, despite the pain and challenges. The source material article ended by describing how many young people were being reckless and potentially spreading COVID-19 because they felt a false sense of invincibility: “and that’s the general kind of invincibility of adolescence: ‘Those bad things you’re talking about, those are other people; that’s not me’” (Khazan, 2021). This echoed the dominant portrayal of young people in the media at the time. However, Eloisa (and several other young people) changed the meaning by instead ending her poem with “invincibility. That’s me.” Here, Eloisa reclaimed her narrative by transforming a negative stereotype of young people during the pandemic into a positive affirmation of strength and perseverance.

Describing her blackout poetry in her own words, Eloisa wrote:

My blackout poem represents my emotional and mental state of mind that took place during COVID-19. COVID-19 took place the year of my graduation in March. I felt a difference around me, a new world, yet to come ahead. From a ‘normal life’ to the unknown, should I continue and drag on this life? The missed experiences of many friendships and milestones. Lost time. But yet we continue to live and celebrate. The media portrayed pessimistic news that caused chaos around the country. There were high rates of depression. But young people demonstrated resilience, preparing for the new world. Despite the negative media and being lost in the unknown, I am invincible.

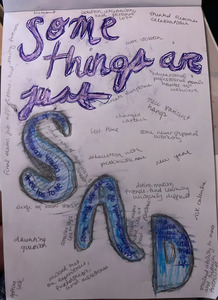

Example 2: Emotional Processing

The line that stood out most to Penny Lane, creating the centerpiece of her art, reads, “Some things are just sad.” Penny Lane’s poem pushed back against the idea that we should all be moving on and trying to go back to “normal”, as if the pandemic never happened, and noted that many people have not had time to grieve and process. By centering “some things are just sad,” Penny Lane made space for her experiences, and our collective experiences, of grief and pain during the pandemic. Penny Lane’s blackout poetry conveys that some things are just sad, and that is okay–we can process those feelings without pretending it never happened or putting a positive spin on it. Describing how creating her blackout poem helped her process her feelings, Penny Lane shared, “I think that it just helped me like physically process things instead of – and like have it kind of leave my body instead of it being all in my head. Because obviously like a lot of it, a lot of like the anxiety or grief is like held in the body and it’s hard to kind of know how to like get it out. So the act of like creating art kind of allowed for like that process of like expelling some of it.”

Although the other young adults created digital blackout poetry, Penny Lane decided to create her poetry by hand on paper. Instead of blacking out the words she did not want to use, she transferred the words she did want to use to a new piece of paper. Penny Lane’s choice to create her poem by hand was also a way to reject the norm of everything being digital during the pandemic. Describing this, Penny Lane said, “It was given as a digital assignment, but I had just decided I wanted to do it by hand instead because it just helped me process it. And [facilitator] also mentioned like we are spending all day, every day on our computers…he suggested that the fact that I wanted to do it by hand was kind of like a rejection of spending all day on the computer…And I definitely agree with that…like I just need to get out of like staring at a screen and typing all day. So like creating art that’s not on a computer just like helps break out of that a little bit, you know?”

Discussion

Recent scholarship has emphasized the importance of integrating social-emotional learning and mental health support strategies into YPAR (Nash et al., 2024). This paper addresses that call by demonstrating how blackout poetry, a creative arts-based method, can be incorporated into YPAR to promote emotional processing while also challenging adultism. Critical reflection in YPAR is designed to foster critical consciousness, which empowers youth to recognize and challenge unjust systems (Diemer et al., 2016). Work around critical consciousness development tends to focus on cognitive and intellectual processes; however, this process can be deeply personal and emotionally taxing, particularly for young people who are most impacted by inequities. Systems change takes time, and YPAR can be harmful if youth are not prepared to cope with disappointment when their recommendations or actions are not immediately supported (Nash et al., 2024). Because of this, intentionally supporting young people’s wellbeing should be a key component of critical reflection and critical consciousness development. Integrating arts-based methods, blackout poetry in particular, into the critical reflection process supports both critical reflection and emotional processing, building connection among youth to sustain them in longer term advocacy and systems-change work.

In our National Young Adult Wellbeing Network (masked for review), blackout poetry offered young people a chance to reflect on their experiences during COVID-19, reclaim their narratives, and challenge the dominant adult-driven and deficit-based discourse about young people during COVID-19. Through the process of creating and sharing their blackout poetry, young people were able to process their emotions, including grief and frustration, and also showcase their resilience. For example, in Eloisa’s blackout poetry, she expressed her disappointment about missed developmental milestones and uncertainty about the state of the world, while also highlighting her strength and persistence. For Penny Lane, blackout poetry gave her the opportunity to be mindful and accepting of her emotions, rather than dismissing, judging, or ignoring them, something she often did not have time to do in her day-to-day life.

Our two blackout poetry exemplars illustrate how socio-emotional work is essential in critical consciousness efforts. The use of blackout poetry for emotional processing in our project aligns with literature highlighting the therapeutic and emotional benefits of art and creative expression. For example, research on arts-based methods has shown that engaging in art, such as poetry, can help individuals process trauma, express emotions, and foster a sense of wellbeing and healing (Goessling, 2020).

This paper also contributes to the field by providing practical, step-by-step guidance on how blackout poetry can be used in YPAR projects. Although there is much literature about YPAR outcomes and processes (Anyon et al., 2018), there is still a gap around practical descriptions of specific methods–a gap that the Journal of Participatory Research Methods has been working to fill by publishing rich descriptions of participatory processes and methods, including photo collages and near-peer interviewing (Carson Baggett et al., 2022), participatory mixed theater methods (Garbovan, 2024), virtual World Cafe Method (Kinney & Kinney, 2024), and many more. Other rich descriptions of YPAR methods, including the Five Whys Method (Kohfeldt & Langhout, 2012), focus on critical consciousness development. We add to the literature by presenting blackout poetry as a tool that supports combatting adultism and emotional processing within YPAR. Ultimately, blackout poetry can be a powerful tool in a YPAR toolkit—one that supports young people to process their lived experiences and emotions while also pushing back against adultism.

Limitations and Future Directions

The purpose of this article is to illustrate blackout poetry as a method, rather than to analyze participants’ artwork. Because of this, we did not fully examine the rich stories in each young person’s blackout poems. Additionally, our small sample size limited our analysis possibilities, and we were not able to deeply examine race, gender, and other intersecting identities within the poetry. Future research could address these limitations by analyzing blackout poetry using an intersectional lens. Further, we selected the art modalities and source material for young people. We had pragmatic reasons for doing this (especially time), but the choice of forms of artistic inquiry and source material could have been made by our young adults. In YPAR, these trade-offs limit youth agency. It is important for practitioners to be transparent with themselves, with youth, and readers of literature about these choices as a form of accountability.

Conclusion

This paper demonstrates the potential of blackout poetry within YPAR as a tool for emotional processing and challenging adultism. In our project, blackout poetry served as a way for young people to explore their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, expressing both their grief and resilience while challenging deficit-based narratives about youth. Additionally, blackout poetry is one way to integrate social-emotional supports into YPAR, ensuring that young people’s wellbeing is paramount during critical reflections on systemic inequities.