Background

The current report describes the graphic medicine methodology implemented in It’s a Journey., a project applying a participatory action research (PAR) approach to research endometriosis among TGD people. Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) people are individuals who do not identify with the gender assigned to them at birth (Coleman et al., 2022). They often experience minority stress as a result of historical marginalization and are disproportionately affected by social and health disparities compared to cisgender individuals (Mezza et al., 2023; Tan et al., 2019). Endometriosis is a chronic condition characterized by cyclic pelvic pain that can greatly affect one’s quality of life (Giacomozzi & Nap, 2022). The dominant discourse narrates endometriosis as a “women’s condition” thus enforcing a binary gendered framing it instead of focusing on the relevant sex-related biological factors that interplay in its pathophysiology (Jones, 2021). However, studies find that TGD people assigned-female-at-birth (AFAB) are disproportionately affected by endometriosis, and that the healthcare system is inadequate to respond to their health needs (Eder & Roomaney, 2024; Giacomozzi et al., 2024; Kaltsas et al., 2024). This often results in missed diagnoses as well as ineffective treatment plans. Little is known about the experiences and the needs of TGD people with endometriosis, who are hardly included in knowledge generation and decision-making processes (Ellis et al., 2024).

Project design

Graphic medicine as participatory method within a PAR approach

PAR is a research approach that emphasizes the significance of experiential knowledge in addressing challenges caused by inequitable social structures and in shaping and implementing transformative alternatives (Cornish et al., 2023). The PAR approach engages the leadership and active participation of people directly experiencing inequities, empowering them to drive emancipatory social change by conducting research to generate new knowledge (Baum et al., 2006; Cornish et al., 2023). As described in its manifesto, graphic medicine is a method that combines “the principles of narrative medicine with an exploration of the visual systems of comic art, interrogating the representation of physical and emotional signs and symptoms within the medium” (Czerwiec et al., 2020). This medium exploits a unique combination of visual elements (illustrations, speech bubbles, onomatopoeia, etc.) and in this unique way not only narrates but also literally makes visible otherwise silenced experiences (Green & Wall, 2020; Venkatesan & Peter, 2019). We selected this participatory method as it is understood to be fourfold: at once a disruptive movement, an education tool, a therapy, and a vehicle for community formation (Venkatesan & Peter, 2019). Graphic medicine was chosen for its capacity to create and disseminate knowledge while — or actually because — it is a process of active community engagement and empowerment (Green & Myers, 2010; McNicol, 2016). Further, it is proven to be particularly helpful in addressing gendered health disparities through queer and trans scholarship, which suited our project objectives (Councilor & Fink, 2024; Joy et al., 2021). Graphic medicine, in fact, allows for more creative and just representations of bodies that fall outside of societal norms (Cosma et al., 2020; Green & Wall, 2020; Joy et al., 2021). It enables the team to decide not only which bodies matter, but also how, when, and where in the visual and narrative space they should be located (Councilor & Fink, 2024). Given TGDs’ structural marginalization, it is an excellent medium to explore, focus, and linger in the marginal and liminal spaces that this community occupies. In this sense, graphic medicine is a tool to enlarge margins to full-pages and thereby re-center experiences too often relegated to footnotes (Czerwiec et al., 2020; Green & Myers, 2010).

Objective

This report describes the participatory process that led It’s a Journey. The project aimed to (1) contribute to the broadening of endometriosis narratives toward gender inclusivity, (2) raise awareness of its high prevalence in the TGD community, and (3) educate healthcare providers and professionals on TGD-sensitive diagnostics and treatments. The final graphic medicine product is meant to serve as a bridge between academic research and the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT+) community, while actively engaging and empowering this historically marginalized social group. Through this report, we strive to illustrate the use of graphic medicine methodology with a PAR approach and reflect upon its strengths and limitations for this project.

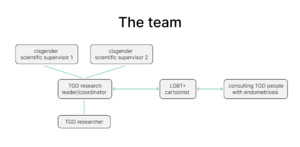

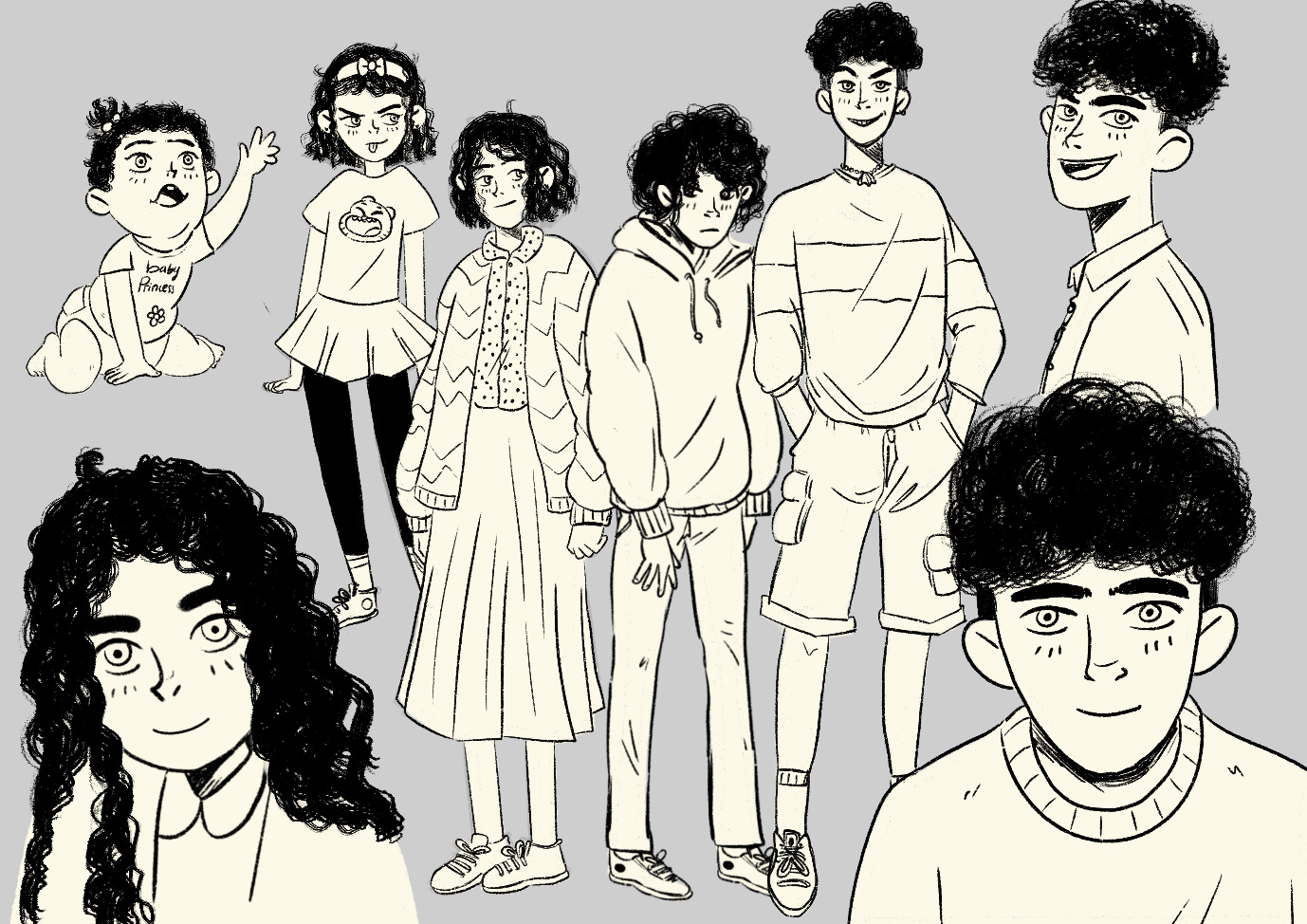

Creating a core team

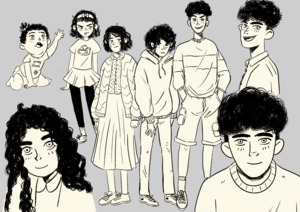

Prior to funding acquisition, the project proposal was conceptualized and discussed among TGD people with/out endometriosis, endometriosis researchers and HCPs as well as LGBT+ activists. Once the funding was assured, a final team was assembled combining members active in academia and/or in the LGBT+ community. The two main organizations involved were a Radboud University Medical Center, a University Hospital in the Netherlands, and the Treat it Queer Foundation, an international small-scale NGO dedicated to health justice for the queer community. The core team involved two junior TGD transmasculine endometriosis researchers supervised by two senior female cisgender scientists, one professional LGBT+ cartoonist, and two consulting TGD people with endometriosis (Figure 1). It was crucial to us that the research was TGD-led to counteract hegemonic biomedical knowledge acquisition and cisnormative gendered systemic power structures, thus ensuring more equitable dynamics among project members and comprehensive data generation.

Project implementation

Idea generation phase

Our first session was an online idea generation during which the core team discussed characters’ features and relevant themes that should be represented. Foundational design choices were made at this meeting, e.g. relating to color palettes and illustration style.

Content development

After the idea generation, the core team met several times online for short meetings, and for whoever possible sometimes in person for full day work. During this process, we decided to include three main elements in the final product. These were:

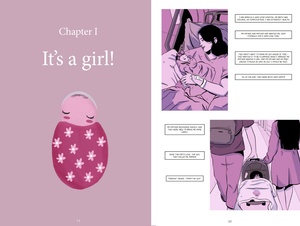

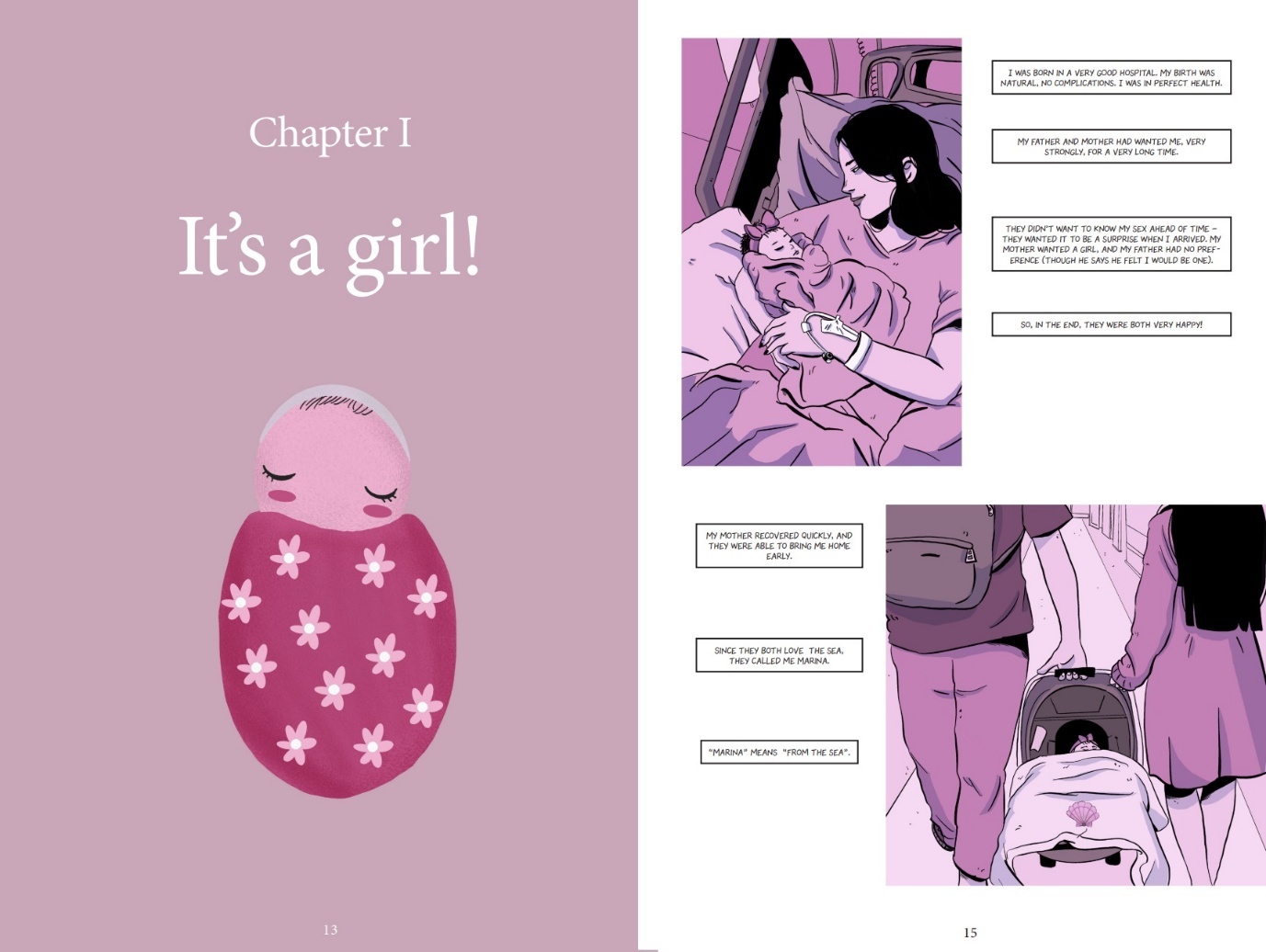

- Fictional storyline: the cartoons illustrate the biography of Colt, a fictional transmasculine non-binary person with endometriosis, from their birth until their late 30s. The story develops along with the character weaving together different themes, i.e., coming to terms with being gender diverse, internal and external acceptance, living with a chronic illness, intimate relationships and family planning as a TGD person with endometriosis, and the role and formation of (nontraditional) families. Color is used in a narrative way, and each chapter focuses on a single, story-relevant and symbolic, dominant color. For example, the first Chapter — titled “It’s a girl.” — uses a palette consisting exclusively of pink hues (Figure 2).

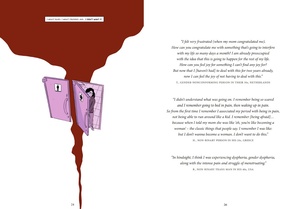

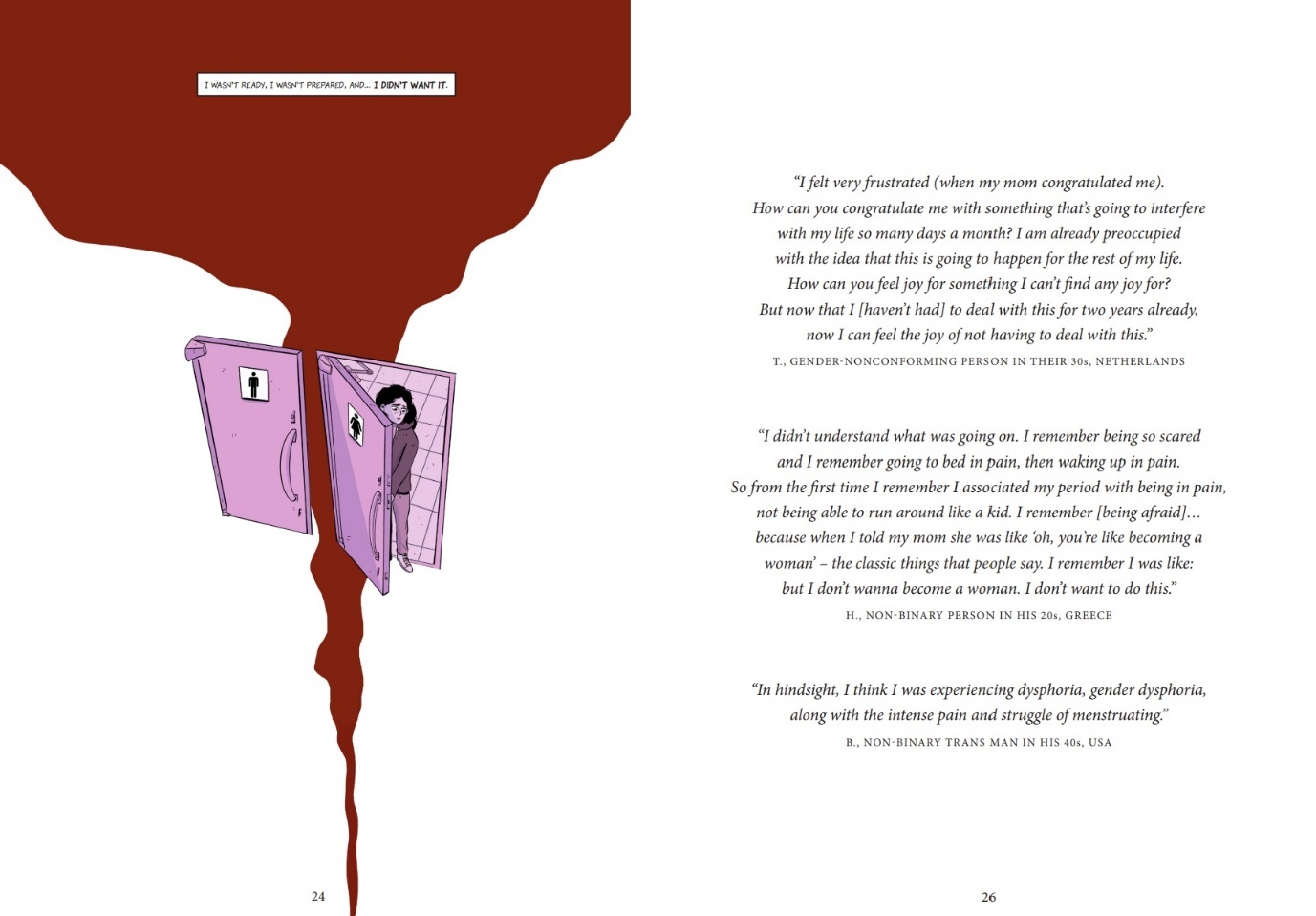

- Quotes from previous qualitative research: to complement the fictional aspect of the cartoon story, we have inserted quotes from focus groups with TGD persons with endometriosis. The research methodology that led to the generation of those data is described elsewhere (Giacomozzi et al., 2025). The focus groups were conducted online and included 14 TGD people with endometriosis based in eight different countries to investigate their experiences and needs relating to endometriosis and gender. The quotes are located on designated pages at pertinent intersections with the fictional storyline, to showcase the reflection and grounding of the fictional themes in real lived experiences. For example, when Colt gets their first period, the featured quotes refer to the experiences of participants with menarche “I didn’t understand what was going on. I remember being so scared and I remember going to bed in pain, then waking up in pain. So, from the first time I remember I associated my period with being in pain, not being able to run around like a kid. I remember [being afraid] …because when I told my mom she was like “oh you’re becoming a woman” -the classic things that people say. I remember I was like: I don’t want to become a woman. I don’t want to do this” -H., non-binary person in his 20s from Greece (Figure 3). Later in the book, Colt is considering medical gender transition, and a quote was added to reflect a real lived experience relating to this “I had no business being in that body, if that makes any sense at all?” -J., non-binary transmasculine person in their 20s from the Netherlands.

- Medical information: each chapter features one relevant topic with which HCPs should be familiar, such as diagnostic tools and treatment options for endometriosis for TGD people. The themes of these sections were identified by the core team and later weaved into the storyline. Mostly, these matched the development of the character storyline as they represent typical milestones in one’s endometriosis and gender journey, such as getting diagnosed and treatment. At times, the storyline was developed in a certain way to match the medical themes we wanted to touch upon, for example when there is a timelapse in the storyline so that Colt and their partner go to a doctor’s appointment to ask about fertility preservation options, even if only a few pages were dedicated to their love story beforehand and therefore it would have not be logical to see them thinking about family planning already. The content of these informational pages was developed by the junior researchers and supervised by the senior scientists separately. References to academic literature and additional resources were included to enable further education of HCPs while validating the given information by showing how they are supported by the current scientific discourse.

Core teams feedback rounds

Frequent community checks regarding visual or other minor design or narrative choices were performed through quick communication channels, such as WhatsApp and phone calls (e.g. to choose Colt’s haircut or the cover design). Structural feedback rounds were carried out with scientific supervisors (two supervisors for two rounds) to assess the medical information, and with the TGD people with endometriosis in the core team (two individuals for two rounds) to outline, (re)think and continue Colt’s storyline. Feedback rounds were both in written form through emails and shared documents, as well as orally in the form of group discussions. The meetings were facilitated by the main junior TGD researcher, and the cartoonist was always present. Other members of the core team participated based on the project’s needs and their availabilities. Additional community experts were approached for their specific lived experiences and/or areas of expertise — for example, a TGD linguist was consulted to name the characters appropriately. Feedback from early reception described below was also considered in the development phase.

Dissemination and early reception

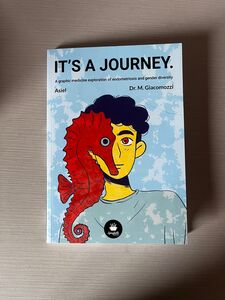

During the implementation phase, the project process and the preliminary results were presented at (1) the monthly meetings of the Treat it Queer Foundation (about 8 people each meeting). (2) two events hosted by Share-Net, i.e. the funder (approximately 35 participants each event), (3) one scientific meeting held at Radboud University Medical Center (about 30 participants). Early feedback by HCPs and LGBT+ activists was integrated in the following project phases. For instance, HCPs suggested to simplify medical information to be accessible to HCPs with different backgrounds, and LGBT+ activists gave guidance on how the love story subplot between Colt and their partner should have developed into a long-term relationship. Graphic medicine was particularly praised as an innovative method to convey complex medical information in an accessible and appealing approach for HCPs. Many academics appreciated how this method enabled them to make results from previous research more accessible to a wide audience, while actively engaging with an otherwise marginalized community. The main themes addressed in the knowledge product are (1) endometriosis, (2) gender diversity, and (3) their intersection. People who were not familiar with any of these topics reported that the product was helpful in learning more about them globally. At the same time, individuals who were familiar with one theme but not with another — e.g., someone who works in endometriosis care but is not familiar with the LGBT+ community — still found the product appealing and educational, to shore up their information shortcomings. Knowledge uptake was said to be facilitated by the fact that the medical information is clearly divided from the storyline and quotes, thus one can choose to linger more or skip pages based on their prior knowledge and/or interests (Figure 4). TGD people with endometriosis who were not involved in the project implementation also gave early feedback and expressed discontent about the fact that the main target of the educational tool was HCPs and not the community itself. At the same time, they reported feeling validated and represented by the product which also provided them with the opportunity to read relatable stories and experiences. This feedback was particularly considered during the remaining development of the project, and especially for its dissemination. Therefore, we strove to ensure that It’s a Journey. is actively distributed to the TGD community and becomes as accessible as possible. We believe that community members can find not just validation but also important information in its pages — information they can then wield as a tool to facilitate critical conversations with their HCPs.

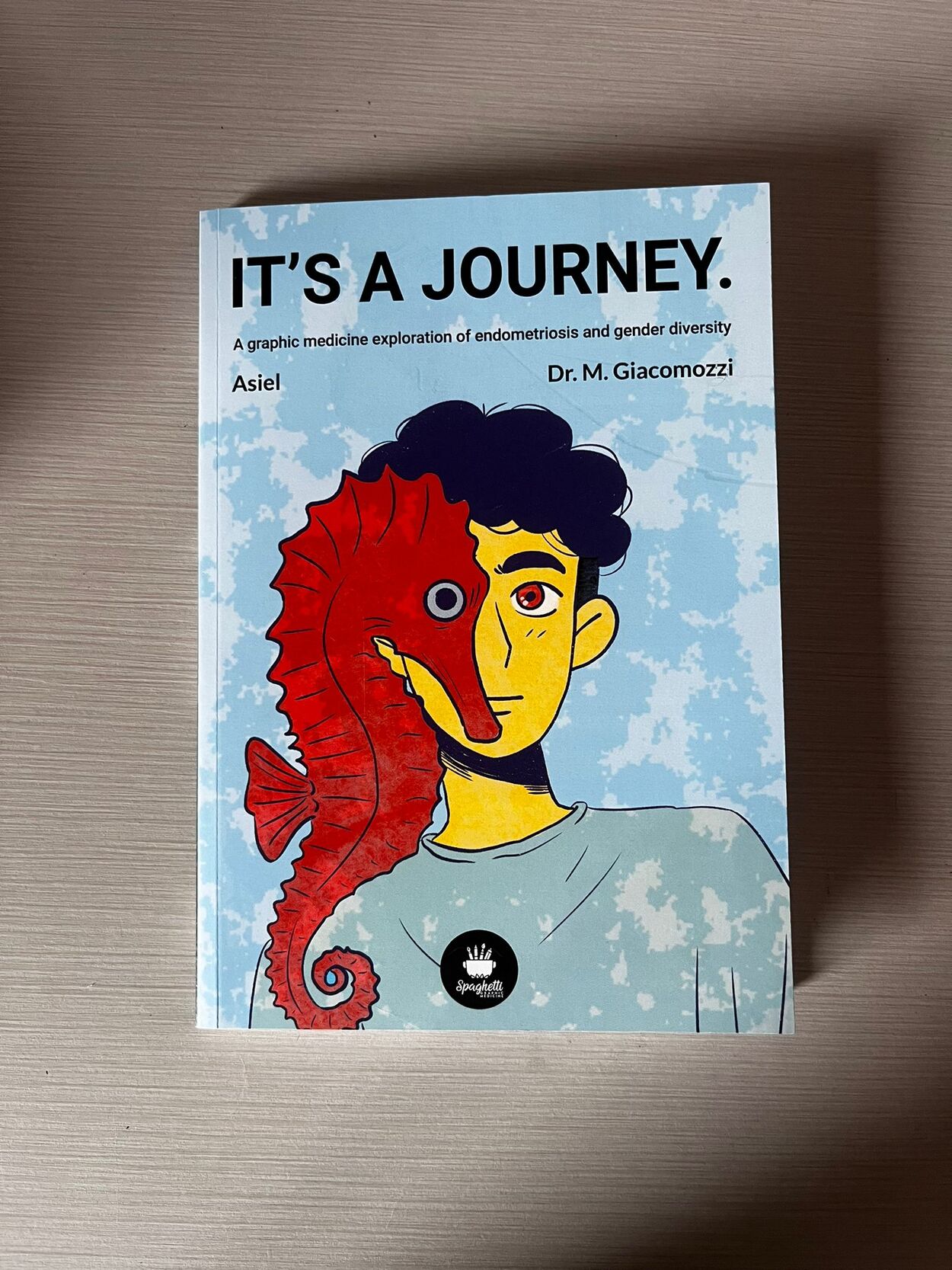

The product is currently available in digital format and as hardcopies (Figure 5). It is disseminated through several online channels not only of the participants’ affiliations and the funding organization, but also through many patients’ associations and LGBT+ groups. Hardcopies are distributed at scientific events for HCPs about endometriosis such as the World Endometriosis Conference, and at community events like Beyond the Binary Day in Nijmegen, Netherlands. The product is further incorporated in the Treat it Queer Foundation workshops that are offered to medical students and HCPs in many medical faculties and hospitals across Europe and Canada. The team is working at expanding press coverage of the project to include, among others, Medisch Contact, the medical journal of the Netherlands, and TRANSmagazine.

Strengths and limitations

Graphic medicine was an effective methodology to meet project objectives, operating along each of the four pathways highlighted by Venkatesan and Peter (2019): as a form of disruptive movement, an education tool, a form of therapy, and as community formation. Using illustrations in health research enabled us to convey complex medical information relating to both endometriosis and gender in an accessible format (“graphic medicine as an education tool”). Moreover, the creative aspect of making a cartoon contributed to a stimulating, inspiring, and fun team process that fostered both individual and community empowerment cross-bridging between academia and LGBT+ activism communities (“graphic medicine as community formation”). Another advantage of using an illustrated medium instead of a photovoice or video documentary was that it allowed us to depict consciously reflexive and arbitrary representations of how especially TGD bodies look — or don’t (“graphic medicine as a disruptive movement”). This disrupted the otherwise hideous task of “looking for people who look a certain way” to have a representative final product. For example, we wanted to show fat bodies to counteract the overrepresentation of slim, androgynous, and white nonbinary bodies over other TGD body types. Therefore, we simply asked the cartoonist to illustrate more fat bodies, instead of having to select participants with certain body types. In this way, illustration allowed us to sidestep common pitfalls in representations of marginalized groups, such as tokenism and stereotyping. Specifically relevant to the TGD community, another great advantage of this graphic medium presented in the ability — within the same product — to represent Colt, a TGD character, at different points in their gender transition without risking triggering gender dysphoria. Using illustration, it was possible to show an individual’s transition without requiring a person to dig into old personal records or problematic “before/after” pictures.

Similarly, the storyline was malleable, able to adapt to the group’s input and did not rely on a single testimony. This permitted us to combine and incorporate various real lived experiences and to choose for each chapter/scene what the group found most relevant to tell. In this fashion, for example, it became clear during the idea generation phase that the team wanted to prioritize an encouraging “happy ending” over a (unfortunately) more realistic one to uplift and provide inspiration and strength to TGD people with endometriosis who may read the book (Figure 6). This conscious choice for the ending contrasts with the dominant discourse in both endometriosis and TGD-related media which favors hopeless, helpless, and sensationally catastrophic endings (“graphic medicine as therapy”).

However, graphic medicine also presented limitations, which were often the flipside of the strengths outlined above. In fact, a limitation intrinsic to graphic medicine was the necessary restriction of representation given by this method. Illustrating someone’s story implied deliberately choosing not only a storyline, but also how the characters looked like and spoke, their mannerisms, their flaws, their personalities. Inevitably, this meant every time we made a choice, we opted to represent someone’s experience and not someone else’s. In this we tried to be as faithful as possible to our own experiences and previous research data. For example, the main character is white because we did not have sufficient background among us or our data to tell the story of a Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) person (Giacomozzi et al., 2025). We are aware that BIPOC experiences are more often silenced than white ones and recognize that this conscious choice — though motivated by data and our desire to avoid misrepresentation as it may be — contributed to this continued disparity in representation (Figure 7) (Bougie et al., 2022; Katon et al., 2023; Westwood et al., 2023). Further studies are necessary to assess the impact and reception of the final product, e.g., through a questionnaire dispended to the readers. This project was further limited by logistic restraints such as the total project timeline being constrained to a mere eight months. This placed not-insignificant strain on the team members, who worked under great time-sensitive deadlines, and significantly reduced the possibility of large-scale idea generation sessions and extensive community checks. We recommend carefully considering the workload of such a project beforehand and keeping reassessing it periodically over the project lifespan, especially when working with marginalized communities that already operate under resource-restricted circumstances. We were fortunate to have received funding which allowed us to compensate people financially for their time and input, partially mitigating this issue. Ensuring sufficient funding to compensate research participants for their work and expenses should be pivotal for any research with a PAR approach.

Conclusion

Taking a PAR approach to graphic medicine is useful to collect and tell the stories of otherwise marginalized people, maximizing the impact of enriching community engagement. It allows for the active involvement of individuals and groups with diverse backgrounds, facilitating the creation of mixed teams with both academics and activists. It’s a Journey. was in itself a journey, a process as well as a product that we believe will help shift the narrative around endometriosis and gender diversity, thus contributing to social and health justice through meaningful community engagement.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to all the people who took part in the focus group whose outcomes have been integrated into the final product. We would also like to offer special recognition and gratitude to: Anna Mai (they/them), PhD, postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, for coming up with original and well-suited names for the characters and Nicol Moran (she/her), coordinator at Share-Net, for the unwavering support throughout all phases of this project.

Funding

This project was sponsored by Share-Net International through an activation fund granted to the Treat it Queer Foundation under project number 10201-2404.03.1.