Background

Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR) is effective in facilitating collaborative work for testing interventions and improving health behaviors (De Las Nueces et al., 2012; O’Mara-Eves et al., 2013; Ortiz et al., 2020; Wallerstein et al., 2019). Trust develops as partners share in decision-making and gain equitable access to resources (Israel et al., 1994; Jagosh et al., 2012). Challenges arise when engaging diverse participants across the community and professional hierarchy. CBPR participants who are professionals working in communities are often more highly regarded, listened to, paid more, and have greater access to resources than participants who represent the population being served by the intervention. These representatives experience disparities and are often impacted by social determinants of health. They may rely on professionals for services and resources. There is a risk of professional participants having more power in the CBPR process due to their professional roles and assumed superior knowledge (Labonte & Laverack, 2001). Among professional participants, status differences may also exist based on education, position, and organizational resources. This dynamic can lead to tokenism where participants with less power may simply conform to the ideas of those with greater influence. These challenges necessitate CBPR protocols that minimize hierarchies. Authentic, effective CBPR partnerships are unlikely to develop without these protocols (Ortiz et al., 2020).

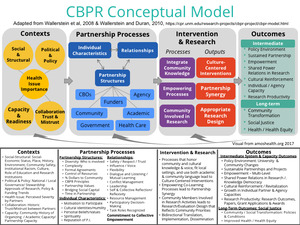

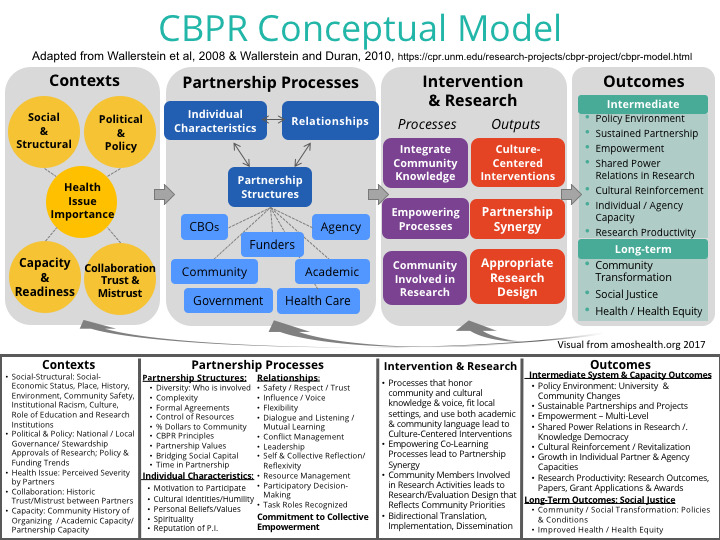

The CBPR Conceptual Logic Model (CCLM) was ‘created to map the pathways between CBPR contexts and participatory processes and policy and program outcomes’ (Cacari-Stone et al., 2014, p. 1615). The model has improved the ability to understand, map, and evaluate participatory processes (Wallerstein et al., 2020). (Figure 1). However, the literature on CBPR processes lacks detail on specific strategies for creating a CBPR process, especially in settings with extensive power differentials, such as projects where low-income parents are participating with service providers, education professionals, and researchers. One scoping review stated that despite the growth in partnership research with community members such as parents engaged as co-researchers, “explicit guidance on the process—how to actually do it remains sparse” (Shen et al., 2017, p. 544). In such environments, CBPR researchers require strategies for establishing meaningful, equitable relationships, actively involving all participants, and fostering effective group dynamics (Wallerstein et al., 2019). A multi-case study analysis of power identified some strategies such as collaborative structures, community as experts and decision-makers and translation teams, and co-learning (Wallerstein, 2008).

Psychological Empowerment Theories in Community-Based Participatory Research

Psychological Empowerment Theory offers theoretical guidance for developing practical strategies when designing and implementing CBPR (Christens et al., 2023). Psychological empowerment is the process of gaining mastery over tasks and resources, which helps an individual feel capable of carrying out the tasks (Llorente-Alonso et al., 2024; Zimmerman, 1995). As an individual increases their empowerment in a specific setting such as a research project, they actively participate in project tasks.

Despite the inherent link between psychological empowerment and CBPR, it is seldom expounded upon or measured. The constructs of Psychological Empowerment Theory, specifically cognitive and relational empowerment, are rarely applied to the implementation and evaluation of the CBPR process (Christens et al., 2023). Yet these theoretical constructs can enhance how researchers implement CBPR. Cognitive empowerment involves improving understanding and skills to better navigate and influence one’s environment, to gain control over one’s life (Zimmerman, 2000). Relational empowerment is the interpersonal and social aspect of empowerment that facilitates an individual gaining power and control over their lives (Christens, 2012). Applying both constructs to the CBPR process can facilitate meaningful, equitable relationships and effective group dynamics. It also aids in the evaluation of CBPR by articulating the commitment to empowerment.

We propose incorporating relational and cognitive psychological empowerment components into the CBPR Conceptual Model (Wallerstein et al., 2020; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). Next, we present the design and implementation of a CBPR case study, Communities for Healthy Living (CHL), to demonstrate how adding psychological empowerment when designing and implementing a CBPR process helps researchers create an explicit participatory process that facilitates equitable participation and equalizes power.

Enhancing CBPR Conceptual Logic Model with Cognitive and Relational Empowerment

Incorporating cognitive and relational empowerment constructs into the CBPR Conceptual Logic Model enhances the model’s utility for guiding researchers to develop authentic partnerships that empower all participants for equal participation (Christens, 2012; Zimmerman, 2000). Table 1 provides definitions of cognitive and relational constructs and their alignment with components of the CBPR Conceptual Model (Wallerstein et al., 2020; Wallerstein & Duran, 2010).

The application of the sub-construct of Cognitive Empowerment, Critical Awareness, in relationship development prompts the facilitation of an iterative process of open discussions, activities, and reflection. Applying critical awareness to discussions leads to the acknowledgment of power dynamics and hidden agendas among partners, which prompts focusing on participants developing relationships to achieve equity in participation (Christens, 2012). Applying Critical Awareness to activities and trainings can facilitate participant identification and understanding of root causes of health disparities. This process can lead to understanding causal agents, another construct of cognitive empowerment that involves analysis of disparities and root causes of inequalities (Christens et al., 2023). A key aspect of Critical Awareness is the understanding of social and cultural realities that impact people’s lives (Peterson, 2014). Cognitive Empowerment is contextual; therefore, the analysis of causal agents focuses on the research topic, which can result in more salient intervention components and empowering outcomes among participants. A CBPR process applying cognitive empowerment would include trainings and activities to ensure skill development to equalize participation. This process can also promote transparency of power dynamics if researchers apply the construct to the evaluation of the CBPR process.

Relational empowerment aligns with Partnership Processes within the conceptual model. The application of Relational Empowerment constructs when designing the CBPR process can facilitate the partnership process leading to high-quality active participation of all participants. This can eliminate the risk of tokenism. For example, the Collaborative Competence construct can guide researchers to design activities to foster group identity and more sustainable collaboration in which diverse group members are effectively and equally participating in the research process. Bridging Divides (Relational Empowerment) can occur if researchers embrace cultural identities, design strategies and activities for reciprocal communication, share leadership, and encourage community management of the researchers (CBPR Conceptual Model concepts). With Bridging Divides in mind, researchers train participants, so they have the knowledge and skills to equally participate in research. Further, partners can be encouraged to share knowledge and leverage their networks to facilitate the empowerment of new Community Advisory Board (CAB) members (Facilitating Others’ Empowerment of Relational Empowerment) (Christens, 2012). In summary, incorporating relational empowerment constructs into the Relational and Individual Dynamics of the CBPR Conceptual Logic Model (Figure 1) can explicate the constructs in ways that facilitate the application of the model (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010).

Description of Case Study: Communities for Healthy Living Project

We present a CBPR case study, Communities for Healthy Living (CHL), a childhood obesity intervention within Head Start, to demonstrate the methodological significance of incorporating cognitive and relational empowerment constructs into the development of a CBPR process in which there are significant power differentials This case study is based on a 5-year empowerment theory-driven CBPR family-centered intervention trial (2016 and 2019) (NCT03334669) aiming to prevent childhood obesity across 16 Head Start programs in Greater Boston. Funded by NIH (R01DK108200), CHL adapted and scaled up a 2-year parent-centered CBPR pilot project implemented in upstate New York (2009-2011) (Davison et al., 2013). Evaluated with a cluster-randomized control trial with a stepped wedge design, the multi-component intervention served over 1650 children and families through 16 Head Start Centers administered by two partner agencies: Community Action Agency of Somerville (CAAS) and Action for Boston Community Development (ABCD) (Beckerman et al., 2019; Beckerman-Hsu et al., 2020).

Details on CHL’s theoretical background, intervention protocol, and evaluation are available in previous publications (Beckerman et al., 2019; Beckerman-Hsu et al., 2020; Gago et al., 2023). The study gained Institutional Review Board approval at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Boston College when the study relocated (Beckerman et al., 2019; Beckerman-Hsu et al., 2020).

CHL’s partnership structures consisted of a research team that had Head Start administrators from the partner organizations as co-researchers and Community Advisory Boards (CABs). These CABs included Head Start staff and administrators, service providers, dietitians, teachers, and parents. The composition of the CABs is presented in Table 2. Parent participants and teachers used services provided by the agencies and had children participating in Head Start. Among staff participants, there were education and pay differentials. Teachers and the dietitian reported to administrators who were also involved with the CAB. Another power differential was between parents and the rest of the CAB. Staff and administrators participated based on their job roles. Some teachers also had their children in Head Start and therefore had dual roles. However, parents, who were often less educated than all the other CAB members, were representatives of the parent experience rather than a job role. Further, parents received services from the service providers and depended on teachers for their children’s well-being.

Tracking the CBPR Process

CHL’s participatory structures, the research team, and CABs, met regularly to build the participatory process and conduct research activities. Two graduate research assistants (GA) observed and took notes during all CAB and research team meetings to document interactions, activities, and decisions. Meeting notes were used to document and assess the development and implementation of the CBPR process. The meeting notes were compared and combined into one complete set of notes for each meeting. Each CAB had 12 CAB meetings for a total of 24 CAB meetings during the development and implementation of the CBPR process, which occurred during the first year. Notes were also taken during research team meetings, which included the agency co-investigators and other agency staff. Thirty-five research team meetings occurred in the first 12 months of the grant. All 59 CAB and research team meeting notes were uploaded into NVivo 11 to assess the CBPR process and the application of Cognitive and Relational Empowerment in that process.

Coding Process

A codebook using descriptive codes (Gibbs, 2012) with definitions was developed a priori based on concepts from cognitive and relational empowerment theory, the CBPR partnership principles, and participatory concepts that emerged from the CHL pilot (Jurkowski et al., 2015). Two trained graduate research assistants coded the documents in NVivo using the codes from the codebook. They met regularly with the investigator (Jurkowski) to refine the definitions of the codes and add additional codes as new concepts related to the participatory process were identified. The codebook was evaluated for completeness based on the decisions that all codes of interest were developed and defined. Next, the GAs recoded the transcripts using this complete codebook. Interrater reliability was calculated for the two GAs and was between 72-94% for codes included in this paper (Saldana, 2013).

Analysis of Meeting Notes

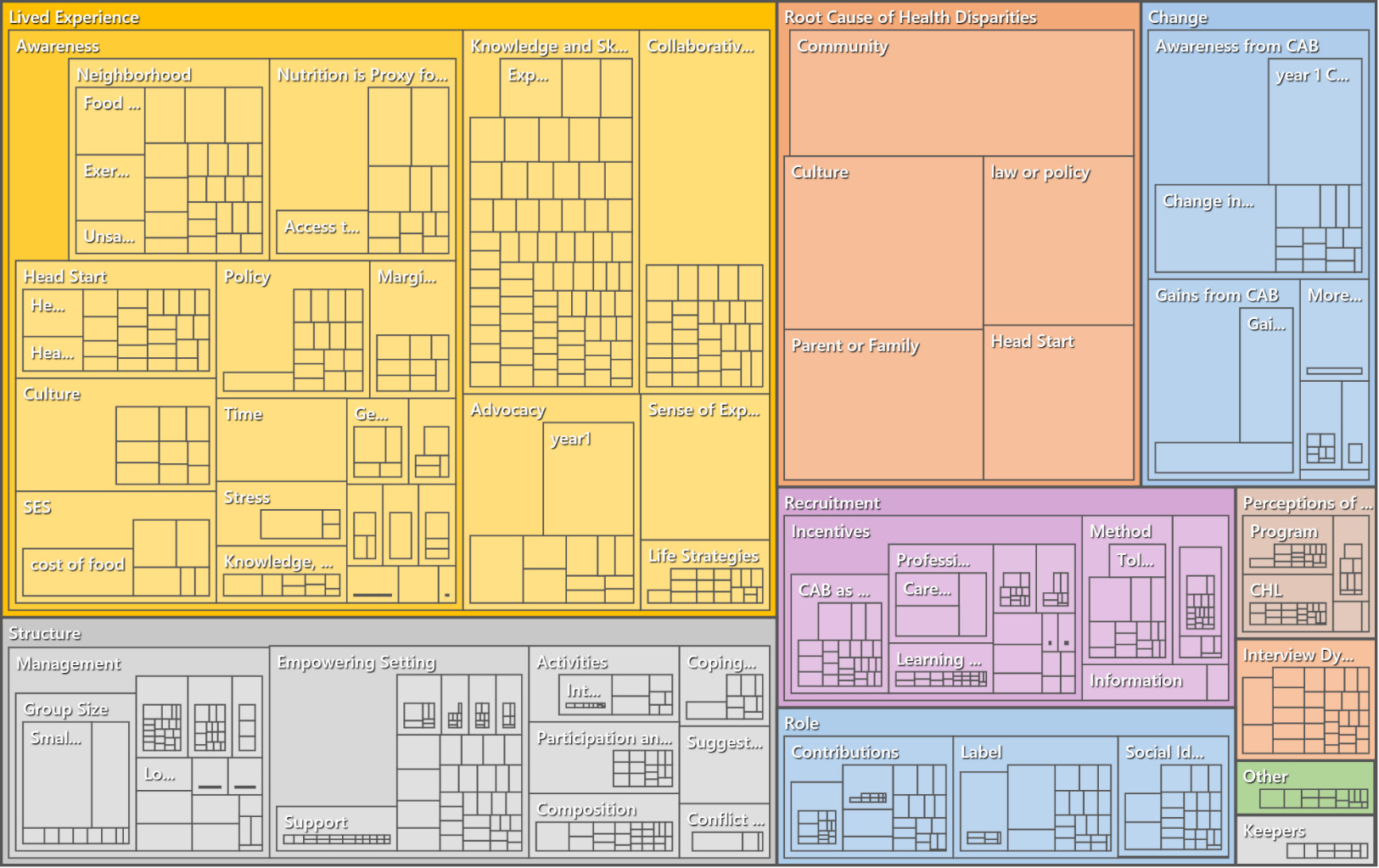

The purpose of analyzing the meeting data was to organize activities and decisions and link specific CBPR activities and decisions to the CBPR Model and Empowerment Theory constructs. A preliminary summary of themes related to empowerment constructs was developed to identify patterns across meetings (Saldana, 2013). A thematic analysis approach (Caelli et al., 2003) was conducted using query searches to identify common terms and consistent meeting processes that demonstrated the application of specific sub-constructs of empowerment. These searches were then assessed as to whether they aligned with definitions and could be grouped to identify CBPR steps and the empowering processes within each step. The graduate assistants created hierarchical charts for visualization of the thematic organization of empowering processes (Braun & Clarke, 2019; Saldana, 2013). This hierarchy chart is presented in Figure 2.

The thematic analysis identified three necessary steps for designing and implementing a horizontal participatory process. These steps are Designing Conscious CBPR Collaboration, Setting a Participatory Tone, and Creating and Maintaining an Empowering Setting. Data analysis identified sub-themes that corresponded with CBPR processes (activities and decisions) that were relationally or cognitively empowering. The sub-themes and the components of cognitive and relational empowerment that they address are also presented. These findings are illustrated in Table 4 and expounded upon in the following sections.

Designing a Participatory Process

Partnership Development

The Principal Investigator (PI) initiated the relationship with Head Start several months before writing the grant proposal by contacting the administrators and meeting with them to discuss the pilot intervention research project to address childhood obesity. This process of developing relationships and collaboration occurred across multiple meetings. The PI established her interest in using a CBPR approach to tailor the pilot intervention to the needs and interests of Head Start in Boston. She not only presented the pilot intervention results and reflections, but she also listened to and considered the ideas and concerns of the Head Start administrators as she began the writing process.

CHL’s partnership development focused on building relational empowerment, bridging social divides, and fostering collaborative competence among the academic investigators and agency administrative staff. Early meetings facilitated idea-sharing and co-learning, which developed collaborative competence. Before the grant writing phase, the principal investigator gave the agency partner $1000 from her start-up package to acknowledge their efforts through the grant planning phase. She was transparent about the NIH proposal requirements and research strategies needed to obtain funding. Agency staff reciprocated by sharing organizational interests, needs, and responsibilities. For example, the agency wanted the grant to cover staff FTE for their participation in the project.

Grant Proposal Phase

The phase of writing the grant proposal is a key time for developing trusting relationships between researchers and partners. In the case of CHL, proposal development involved iterative conversations, multiple exchanges of the grant proposal, and collective decisions on roles and expectations. The relationship between the PI and Head Start administrators was expanded to include an experienced researcher in CBPR. The researchers co-designed the proposed project. For example, the Family Ecological Model and Empowerment Theory were agreed upon as guiding frameworks with the CBPR process, which was described throughout the narrative and budget sections of the NIH grant proposal. To mobilize resources, a substantial sub-award budget for the partner agencies was included, covering staff time and a full-time CHL liaison at each agency. The administrators were written into the proposal as co-investigators and a portion of their FTE’s were written into the budget. The newly created liaison position was designed to facilitate the research process, foster collaboration between agencies, and enhance relational empowerment through ‘facilitating agency staff empowerment’ (see Table 1). Including facility and administration costs in the budget demonstrated a tangible commitment to a true CBPR process aiming for equity and power sharing.

The CBPR infrastructure was laid out in the study design of the grant proposal. The research team and administrators were to convene as a research team that met weekly. To facilitate the participation of those directly impacted by the intervention, the proposal included a Community Advisory Board for revising the intervention and designing the evaluation. Financial resources for the two partner organizations were allocated within the grant proposal budget. Their budget included funding to support the CAB’s and intervention processes. CHL researchers met to plan for funding before receiving notice.

Community Advisory Boards (CAB) were written into the grant and budget narrative as participatory infrastructure. They played a crucial role in facilitating both cognitive and relational empowerment for a diverse group of Head Start and community. The grant proposal timeline allowed a year for developing and implementing the CABs’ participatory process. While administrators often are college educated, Head Start teachers typically have a two-year degree and earn incomes that, at times make them eligible for their own children’s participation in Head Start. Parents with children in Head Start must meet a federal income requirement and few have post-secondary education.

Grant Funding Phase

After funding was granted, researchers and administrators met as a research team on a biweekly basis. The early meetings were to work on establishing the sub-awards. The agencies hired CHL liaisons, whose role was to manage the sub-contract, plan and implement CBPR activities, and be involved in intervention implementation later in the funding cycle.

The research team conferred with ABCD and CAAS agency staff about the details of the CABs and decided to have separate Community Advisory Boards (CABs) for each agency due geographic spread of the Head Start programs. Meeting at Head Start Centers facilitated parent and teacher participation. The CABs met biweekly for the first year of funding, then monthly and later, quarterly post-implementation. The CAB members reflected diversity in professions working with Head Start and race/ethnic backgrounds of the communities served by Head Start. Both CABs included parents with a child in Head Start and Head Start teachers, administrators, and agency staff (see Table 3). A meal was provided at each CAB meeting and members were offered compensation, in the form of a gift card, for their time. All meetings were held during the Head Start day, allowing parents to participate. Classroom coverage was provided for teachers who participated. The sub-contract for the agencies included funding for teacher coverage, meals, and administrative costs for planning and holding meetings at centers.

Setting a Participatory Tone to Facilitate Participation

During the first year, the research team worked closely with ABCD and CAAS, led by the CHL Liaison, to establish collaborative infrastructure. This involved the intentional recruitment of a diverse group of Head Start affiliates, parents/caregivers, teachers, administrators, and professionals to the CAB. To ensure diverse community representation, members included low-income and race/ethnically diverse parents and Head Start teachers as well as professionals who work with Head Start and the university researchers and staff.

The first CAB meetings focused on setting a participatory tone (Table 3, column 2) and involved developing relationships. In doing so, they were facilitating the bridging of social divides and ensuring equitable participation. These included careful agenda planning with activities designed to facilitate aspects of cognitive and relational empowerment to achieve equitable participation by breaking down silos. CAB members’ roles and responsibilities were described in terms of active participation, shared ownership, and the potential impact each member may have on the project. By highlighting that all members were co-researchers with roles and responsibilities, CHL established role equity.

The development of partnership principles was integral to the participatory tone. The process helped develop collaborative working relationships among CAB members while establishing a guiding philosophy for the CAB. The process involved small groups of CAB members deconstructing the 12 general principles from the literature (Wallerstein, 2008) and creating principles reflecting the unique community of CHL’s partnership. Principles were presented by the small groups, then discussed, revised, and voted upon, with final wording determined through majority rule.

Efforts to bridge social divides and “facilitate others’ empowerment” included paying attention to the literacy level of text and minimizing research jargon. The CHL Liaison played a crucial role in making presentations and documents accessible. The CHL Liaison and others continually reiterated that all types of knowledge, such as life experiences, were valuable expertise for revising the CHL intervention. This was also important for building collaborative competence among parent CAB members because they did not automatically see themselves as having a valuable contribution to research. Since staff, CHL liaisons, and academic members received pay for their time, it was important to compensate parent and community CAB members to reinforce equity in expertise. Due to fiduciary rules, CAB members were provided gift cards as compensation rather than cash. CAB members voted on which stores would be preferable. Meetings were held at the Head Start Centers. Early on, the CAB decided to make decisions with majority rule with allowances for ample discussion before finalizing decisions. All decisions were documented in the meeting notes.

Meals were provided at all CAB meetings, which were held in the mornings or early afternoons to accommodate the Head Start schedule. Meetings were held at Head Start Centers and interpreters were provided for those who needed them. Young children were able to attend their Head Start program during meetings and older children were in school. In some cases, parents with infants brought them to the meetings.

Creating and Maintaining an Empowering Setting

Once the culture of participation had been established, it was important to solidify and maintain an empowering setting. CAB meetings were structured in ways to support CAB members’ active participation. The third column in Table 3 articulates activities aimed at creating an empowering setting. The strategy to have small group activities while encouraging different small group members to present to the larger group, facilitated the participation of quieter or less confident individuals. During this process, staff acted as facilitators only if necessary. The CAB process was iterative. Small group work was brought back to the larger group and then decisions that were made were addressed by the research team. All products of the work in revising the CHL intervention were then brought back to the CAB for review. See Table 3, Column 3. The CAB decided to make decisions based on a majority vote in the larger group.

Training was provided to increase critical awareness and research skills to increase cognitive empowerment. The trainings were developed using Adult Learning Theory strategies and case studies of ecological factors that influence childhood obesity. The CAB was trained on the Family Ecological Model, risk factors for childhood obesity, the CBPR approach, and research ethics (Mezirow, 2018). This training facilitated discussions where CAB members applied their knowledge to inform the group about local environmental influences on child health, fostering critical thinking and knowledge-sharing—project-specific cognitive empowerment constructs. Activities were developed to foster critical thinking, encourage sharing of experiences and expertise, and linking that knowledge to ideas for revising the intervention. With this knowledge and skills, non-researcher participants were better able to participate in the revision of the intervention and the entire research process.

Paying attention to diversity in language, culture, and experiences was essential for an empowering setting. Translators were present, and discussions on healthy child-rearing within cultural contexts were encouraged. Activities focusing on revising the Family Ecological Model, considering community and cultural influences on parenting. Not only did these discussions about raising a healthy child facilitate relationship building, but they also helped revise the CHL intervention. These discussions encouraged CAB members to be inclusive of all cultures represented at ABCD and CAAS.

Discussion

Building equitable participatory research collaborations between researchers and community members in a low-resourced setting remains a significant challenge (Yan et al., 2024). Participatory research projects face issues such as researchers dominating discussions and inequitable participation (Hahn et al., 2017; Nyström et al., 2018). The risk of tokenism is heightened in collaborations with socioeconomic and culturally diverse communities in low-resourced settings or when the CBPR process lacks thoughtful consideration of power dynamics and empowerment. This paper argued for incorporating cognitive and relational empowerment into the CBPR Conceptual Model, especially when designing the participatory process, to facilitate the development of strategies to ensure community members’ voices are genuinely incorporated in decision-making.

In this study, the application of empowerment theory constructs aided relationship building between CHL researchers, Head Start administrators and staff, and low-income parents. The CABs’ intentional design, from diverse membership to logistical accommodations such as childcare and meal provisions demonstrated a commitment to reducing barriers to engagement. By compensating participants with gift cards and ensuring cultural and linguistic inclusivity, the CABs reinforced the value of all members’ contributions. This participatory infrastructure fostered both relational and cognitive empowerment, aligning with CBPR principles of equity and inclusivity. CHL conducted trainings so that all CAB members had the background knowledge to revise the intervention components in a way that aligned with the literature and guiding theory as they tailored the components to meet the culture and needs of participating families. The inclusion of resources such as sub-awards, CHL liaison roles, and compensation for participation underscored a tangible commitment to equity.

This study also provides strategies for addressing power differences due to wide-ranging experience and socioeconomic status. This study aligns with comprehensive reviews of participatory research processes that highlight resources, training, communication, relational dynamics, and relationship building as essential elements of a participatory process (Crowther et al., 2023; Shen et al., 2017; Tremblay et al., 2017). Reviews of literature on participatory research with parents identify challenges with resource usage, range of experiences, lack of role clarity, and power differences (Shen et al., 2017). Literature reviews focused on engaging youth and parents also identified the challenges of power imbalances between parent co-researchers and researchers as well as the need for thoughtfully planned engagement opportunities (Crowther et al., 2023; Shen et al., 2017). A multi-case study of power in partnerships found that all communities valued the CBPR approach for equalizing power and the committee infrastructure that supported and prioritized community knowledge (Wallerstein et al., 2019). CHL engaged low-income parents in addition to organization partners, necessitating attention to the power differentials between parent CAB members in addition to between research staff and organizational staff. The intentionally designed committee structure, attention to setting a participatory tone, and empowering activities of CHL’s participatory process addressed power differentials. Like other research, this case study underscores the importance of training, and interactive learning as critical resources for enabling equitable engagement (Crowther et al., 2023; Shen, et al., 201). However, unlike most known published research, this case study detailed intentionally designed strategies. This paper addresses a gap in the literature by offering practical guidance on developing a highly participatory CBPR process by employing cognitive and relational empowerment through carefully planned engagement efforts.

While the CBPR Conceptual Model incorporates collective empowerment and bridging social capital (Wallerstein et al., 2020), our approach suggests that explicitly including relational and cognitive empowerment in the Partnership Processes section of the model can enhance the model and facilitate genuine CBPR processes. Cognitive and Relational empowerment constructs can be incorporated under the section called Commitment to Collective Empowerment (Figure 1). Having these concepts will guide researchers in how to develop a CBPR process that is empowering.

Limitations

This study focuses on a CBPR process in two Boston area communities. The generalizability is limited since the detailed descriptions of the ethnically diverse CHL CAB members are not reported for confidentiality reasons. Like any case study, the context of this study is limited in its applicability, but the suggested strategies and theoretical constructs are transferable. The application of relational and cognitive empowerment in guiding a CBPR process has not been replicated. This case study focuses on the process rather than the outcomes of the participatory process. Further publications will present empowerment qualitative outcomes of the participatory process. Research quantifying the application of cognitive and relational empowerment within CBPR, specifically, within the CBPR Conceptual Model is needed to support the addition of the constructs to the model.

Implications

Incorporating relational and cognitive empowerment constructs within the CCLM has the potential to enhance measurability and contribute to evaluation measures. Empowerment sub-constructs can serve as measurable process and intermediate outcomes of CBPR, further developing the concept of participant empowerment in the CCLM. Future publications are planned to share the evaluation of applying empowerment within the CHL Case Study.

The challenge of achieving genuine participation in research processes, particularly when substantial socioeconomic and power differences exist has been repeatedly identified in reviews. Strategies for ‘how to’ implement a genuine CBPR using empowerment constructs outlined in research publications can offer concrete guidance for implementing CBPR to address health inequities. To foster empowerment and prevent tokenism, this paper suggests the conscious, intentional application of relational and cognitive empowerment constructs during CBPR design and implementation. Incorporating these constructs into the CCLM adds to its utility in facilitating the successful implementation of structural and relational dynamics for a genuine CBPR process.