Compared with their cisgender heterosexual peers, sexual minority (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer) and gender minority (e.g., transgender, nonbinary, genderqueer) populations experience substantial inequities in alcohol-related harms, including increased rates of alcohol use disorder and alcohol-related violence (Coulter et al., 2015; Kerr et al., 2014; Lea et al., 2013; Talley et al., 2016). It has been over a decade since the Institute of Medicine called for more research on interventions to address health inequities among sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations, yet alcohol and other substance use inequities persist (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Mereish, 2019; Watson et al., 2018). Nevertheless, SGM populations have demonstrated resilience to negative health outcomes via activism and through their contributions to participatory research studies across numerous topic areas, including HIV/AIDS, mental health, sexual health, and substance use (Frost et al., 2019; Ricks et al., 2022). Such contributions have unveiled novel intervention ideas and helped elucidate ways in which existing interventions could be tailored to meet the goals of SGM populations (K. Brown et al., 2024; Coulter et al., 2024; Delmonaco et al., 2023; Jadwin-Cakmak et al., 2020). Additional participatory research with these populations can address alcohol-related harms by identifying targets for future interventions, countering power imbalances, promoting co-learning, building on existing strengths, and facilitating the production of mutually beneficial research outputs (Israel et al., 1998).

The factors driving alcohol inequities among SGM populations are complex and interdependent in that they span social-ecological levels (i.e., individual, interpersonal, organizational, structural) and interact within and across these levels, forming bi-directional relationships and feedback loops. For example, structural stigma (e.g., lack of policies and systems to support and protect SGM populations) is associated with increased stigma at an individual level (e.g., sensitivity to rejection based on sexual orientation) (Pachankis et al., 2014). SGM people purportedly engage in substance use to cope with stress from stigma, leading to negative mental health impacts, which can in turn lead to additional stress at an individual level (Meyer, 2003; Mink et al., 2014). Traditional approaches to studying and reducing alcohol-related harms among SGM populations (e.g., analysis of survey data using statistical modeling frameworks) tend to ignore such interdependent relationships and focus on modifying individual-level behaviors without also addressing interpersonal, contextual, and structural factors (Kidd et al., 2022; Moore et al., 2021).

Examining alcohol inequities among SGM populations using complex systems science offers a promising way forward from traditional approaches (Moore et al., 2021). Complex systems consist of factors across social-ecological levels that interact with one another over time to create bi-directional relationships and feedback loops, producing emergent properties that are not explained by any one element of the system (Finegood et al., 2014; Luke & Stamatakis, 2012). Group model building (GMB) is a participatory complex systems science method through which trained facilitators collaborate with participants to produce models (i.e., visual representations) illustrating how salient factors across multiple social-ecological levels interact to drive problems over time (Hovmand, 2014). Through GMB, participants co-create causal loop diagrams by identifying important factors related to the problem of interest and drawing hypothesized causal relationships between these factors. This collaborative diagramming process allows participants and researchers to articulate implicit assumptions about the relationships between key factors and achieve consensus about how these patterns function over time to influence a main outcome of interest, often referred to as a reference mode. The resultant causal loop diagram can be used to identify intervention points across social-ecological levels, examine how intervention effects may disrupt or reinforce feedback loops, and inform other complex systems science studies evaluating potential intervention effects, including systems dynamics and agent-based models.

Researchers have used GMB with diverse collaborators to understand complex system dynamics across a range of different topic areas including drug-related harm, alcohol outlet zoning policy, maternal health, HIV treatment access, physical activity, and obesity (Allender et al., 2015; Bates et al., 2022; Guariguata et al., 2021; Lemke et al., 2022; Matson et al., 2022; Moore et al., 2022; Weeks et al., 2017). The method has not yet been used to understand inequities among SGM, nor alcohol-related harms in this population specifically (Moore et al., 2021). Understanding how best to engage SGM college students with GMB is important given that this population experiences more problems related to their alcohol use than non-college students and other age groups. (Hingson et al., 2017; SAMHSA, 2022; Slutske, 2005).

GMB includes a variety of structured small group activities that can be flexibly combined and adapted based on the needs of different sets of collaborators and the context of the problem of interest. Although these activities have been documented and made publicly available as “Scripts,” stakeholder groups have significant latitude in choosing which activities they do and how they sequence them (Ackermann et al., 2011; Hovmand et al., 2012; Wikibooks contributors, 2022). Previous studies using GMB have varied from a single day-long session to multiple sessions delivered over the course of several days (Bates et al., 2022; Lemke et al., 2022). Per Hovmand (2014)’s problem scoping framework, GMB can be used to achieve fundamentally different goals, including generating consensus around the understanding of a problem and identifying leverage points to address it (Hovmand, 2014). Given the variability in GMB application, it is important to understand how to optimally structure GMB delivery to achieve consensus with SGM populations on what the complex, interdependent causes of alcohol-related harms are and how to modify them.

The primary goal of this paper is to report on the feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness of using GMB in an online setting with SGM college students to achieve consensus on the mechanisms underlying alcohol-related harms and leverage points for reducing those harms, in line with Hovmand (2014)’s framework. We expected that a series of structured tasks would enable participants to generate consensus on these mechanisms and leverage points through the co-creation of outputs that tangibly represent causal links among interdependent factors (Scott, 2019). Furthermore, based on our experience using similar, but different, participatory methods with SGM youth, we hypothesized that our GMB methods would be rated as highly feasible, acceptable, and appropriate by SGM college students (Coulter et al., 2021). By documenting our study procedures and lessons learned, our goal is to provide useful knowledge for future studies seeking to engage SGM college students in group model building. More broadly, this study can inform efforts to center the voices of marginalized populations in understanding complex health issues and potential intervention points.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We held four online ninety-minute sessions, once per week for four weeks in June and July of 2022. Sessions were designed to build upon one another, and we anticipated that holding them once per week would facilitate participant recall of prior sessions while allowing for adequate time to prepare in-between (preparations described further in the next section). We also anticipated that ninety minutes would allow sufficient time for session activities while minimizing burnout among participants.

We used a mix of convenience and snowball sampling to recruit individuals ages 18-25 who were currently enrolled as undergraduate students at any U.S. university, identified as being part of an SGM population, and indicated that they had access to an internet connection and a computer with a microphone and camera. We ascertained eligibility using a web-based, self-administered REDCap screener survey, which we disseminated via a recruitment email and flyer to organizations and listservs (e.g., University LGBTQ Alliance and the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program) associated with the lead author’s university. None of the participants were directly connected to researchers. All who completed the screener survey received a list of inclusive mental health, substance use, and violence prevention resources, including resources specifically for SGM populations.

We also encouraged Session 1 participants to share the screener survey with their friends and advertised our study through a Reddit forum dedicated to survey recruitment. To our knowledge, at least one of the participants recruited a friend to join the study; however, we did not explicitly assess the relationships among participants nor how they found out about our study. Distributing the screener survey online resulted in many respondents who appeared to be internet bots (i.e., web robots) or bad actors (i.e., providing false information), which we identified by examining the timing of survey responses (e.g., very short response indicating potential bots) and calling all invited participants to verify information provided in their screener (e.g., the name of their undergraduate school). A total of eight participants attended GMB sessions for this pilot study; two attended all four sessions and six attended three sessions (Figure 1).

Following each session, participants were sent a $25 gift card as a thank you for their time. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Group Model Building Procedures

A key aspect of our GMB adaptation was the development of online MURAL whiteboards to facilitate group activities (MURAL, 2023). We set up MURAL boards corresponding to the activities planned for each session and practiced implementing each board with the research team. We also developed detailed agendas (e.g., with consent scripts) and PowerPoint slides to share background information about the project with participants.

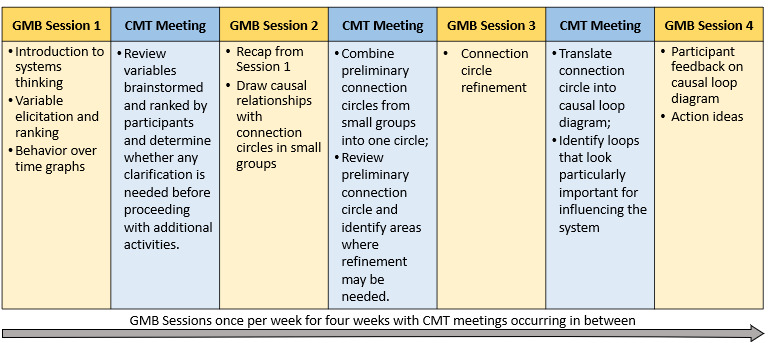

Each session was delivered over Zoom by 2-3 members of the research team and included an introduction to the project and an icebreaker to build rapport among participants. During each session, we obtained verbal consent from participants. Participants then completed activities in MURAL while participating in discussion over Zoom. Each session was audio recorded with participants’ permission. Throughout all sessions, we encouraged participants to take breaks and prioritize their mental health as needed given the sensitivity of the topics discussed. In between sessions our core modeling team (CMT), which consisted of six research team members, met to synthesize findings and prepare for the next session. CMTs are often used during GMB to guide agenda development, refine variables generated throughout the process, and synthesize qualitative and/or quantitative models (Hovmand, 2014). Figure 2 details how we structured our GMB activities across the four sessions, including the tasks completed by the CMT in between sessions.

Session 1: Identifying and Prioritizing Alcohol-related Harms: Following a brief PowerPoint presentation describing general types of alcohol-related inequities in SGM populations, facilitators asked participants to individually brainstorm answers to the following prompt by writing sticky notes on our virtual MURAL board: “What alcohol-related harms could be addressed among LGBTQ+ college students?” Participants then shared what they had written and ranked these variables in terms of importance. For the top-ranked variable, participants discussed how this behavior could change over time, informing the selection of the reference mode. In between Sessions 1 and 2, facilitators reviewed the variables brainstormed and ranked by participants to determine whether any additional clarification or input was needed from participants (e.g., on the definition of the top-ranked variable/reference mode).

Session 2: Creating Connection Circles: Facilitators presented a summary of the variables and themes identified by participants during Session 1 and worked with participants to establish consensus on which alcohol-related harm should be the focus of the causal loop diagram (i.e., what the reference mode should be). As an intermediate step to creating a causal loop diagram, participants created connection circles, which are tools for systematically identifying and visualizing the connections between ideas (see Supplemental Figure S1 and S2 for an example) (Molloy, 2018). Participants individually brainstormed causes and effects of the selected harm across social-ecological levels. In small groups, participants then took turns placing the factors they identified on a circle and drawing arrows to indicate whether each factor caused an increase or a decrease in each of the other factors already on the circle. This process was systematic in that participants assessed the causal relationship between the newly added factor and every factor already on the circle. The output of this session was a set of preliminary connection circles. Prior to Session 3, the CMT combined preliminary connections circles by adding all factors and arrows to a single circle.

Session 3: Refining Connection Circles: Facilitators worked with participants to refine the combined connection circle by adding any factors or connections were missing and modifying any that participants deemed inaccurate.

In between Sessions 3 and 4, the CMT translated the connection circle into a causal loop diagram using Kumu, a freely available online systems mapping platform (Kumu, 2023). As part of this translation process, facilitators organized variables into thematic domains, combined similar ideas, discussed whether other ideas should be broken down into distinct variables, and identified loops that looked important for influencing the system, arranging the causal loop diagram to emphasize these loops (i.e., by moving the variables and arrows around in the diagram to show this). The CMT emailed a PDF of this diagram to participants to review prior to Session 4.

Session 4: Feedback on Causal Loop Diagram and Action Ideas: Facilitators presented the causal loop diagram that they developed, including the decisions that they had made in translating it from the connection circle. Facilitators then asked participants to reflect on the causal loop diagram, including asking them to identify whether any concepts were missing, in need of clarification, or improperly connected. Next, facilitators asked participants to identify which loops seemed most important for addressing the alcohol-related harm they selected. Finally, facilitators asked participants for feedback on which strategies could change the system and thereby address the harm of interest.

Post-Session Follow-up

After the final session, we invited participants to complete a follow-up survey on REDCap, which was web-based and self-administered, like the screener survey. The survey included open-ended questions asking for participants’ feedback on session delivery and the following validated measures: 1) the Feasibility of Intervention Measure (FIM), which ascertained the extent to which participants thought our sessions were successfully implemented online (e.g., “The online sessions for this project were doable”), 2) the Acceptability of Intervention Measure (AIM), which assessed participants’ views on whether the GMB sessions were satisfactory or agreeable (e.g., “I liked the online sessions for this project.”), and 3) the Intervention Appropriateness Measure (IAM), which assessed participants’ perceptions of whether our GMB sessions were relevant, compatible, and suitable (e.g., “The online sessions for this project seemed fitting.”) (de Meneses-Gaya et al., 2009; Weiner et al., 2017). Participants rated each statement using a five-item Likert scale ranging from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (5). Although we did not ask participants to discuss their personal experiences with alcohol during the sessions, we anticipated that their perspectives may have been influenced by the extent to which they consumed alcohol. Thus, the follow-up survey included a validated measure of hazardous alcohol use (i.e., the AUDIT-10) (de Meneses-Gaya et al., 2009). Those who completed the follow-up survey received a $10 gift card.

Data Analysis

We assessed hazardous alcohol use among participants by summing their responses to AUDIT-10 items and determining how many participants scored within the recommended cut-offs (low risk alcohol use: 1≥ AUDIT score < 8; hazardous alcohol use: 8≥ AUDIT score < 15) (de Meneses-Gaya et al., 2009). For FIM, AIM and IAM measures, we computed means and 95% confidence intervals and one-sample t-test p-values for each scale and determined if scores exceeded our a priori benchmark of 3.75 (out of 5.00). These analyses were conducted in Stata 17 (StataCorp, 2021). Finally, using thematic analysis we synthesized feedback that participants provided via open-ended questions (Kiger & Varpio, 2020).

Researcher Positionality and Reflexivity

The team responsible for this study is made up of a diverse group of researchers, some of whom identify as heterosexual cisgender men and women, and some of whom identify as cisgender gay and bisexual men. Five members of the research team identify as non-Hispanic White and one as Asian. The researchers on our team are diverse in their areas of expertise (e.g., substance use, systems science, SGM populations, counseling, and college health education) and roles within academia (i.e., doctoral student, post-doctoral fellow, assistant professors, and associate professors). We took several steps to mitigate potential bias. Prior to delivering this pilot, we conducted a practice session with SGM undergraduate students. These students provided feedback on the session delivery, allowing us to refine our approach before launching our pilot. Research assistants identifying as being part of an SGM population also reviewed our survey instruments, providing feedback on wording. As described above, we also sought to limit our biases by checking our interpretations of session outputs with participants. Using participatory, online tools we also sought to alleviate researcher-participant power imbalances and democratize decision-making in the co-development of the final causal loop diagram.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the eight participants who participated in our study are shown in Table 1. Our sample was diverse in terms of sexual identities represented and years of education completed. Our sample primarily consisted of cisgender women (n=5), although it also included one transgender man and two individuals identifying as nonbinary or genderqueer. Participants mostly identified at White Non-Latine (n=5), although two identified as Black Non-Latine and one identified as Multiracial. The mean age was 21 years (range:18-23). Of the seven participants who completed the AUDIT-10 questions about their drinking, four reported low-risk drinking levels and three reported hazardous drinking levels.

Group Model Building Session Output

Session 1: Identifying and Prioritizing Alcohol-related Harms: Participants brainstormed and discussed a range of alcohol-related harms experienced by SGM college students. These included repercussions related to social relationships (e.g., challenges maintaining relationships with SGM peers), work/academic responsibilities (e.g., missing work/class), and health (e.g., poor mental health, weight gain). Participants also noted that alcohol can lead to adverse reactions to medication for depression and hormone replacement therapy. In ranking these harms from least to most important, participants identified alcohol-involved risky sexual encounters as the most important alcohol-related harm to address among SGM college students.

Session 2: Creating Connection Circles: At the outset of Session 2, the facilitators proposed focusing causal loop diagram development on reducing alcohol-involved sexual violence as the reference mode since this aligned with the top-ranked idea from Session 1 (risky sexual encounters) and CMT research priorities. Facilitators presented the definition of alcohol-involved sexual violence to participants as: non-consensual sexual contact during or after drinking via physical force, coercion, or taking advantage of one’s inability to consent (Cantor et al., 2020).

Participants then used MURAL to brainstorm causes and effects of alcohol-involved sexual violence, generating approximately 50 unique ideas across social ecological levels (e.g., internalized homophobia/transphobia, victim blaming, normalization of sexual violence, alcohol/sex education programs) and transferring these ideas to connection circles. An example of the output from this session is shown in supplemental Figure S1.

Session 3: Refining Connection Circles: To refine the combined connection circle from Session 2, participants added additional concepts brainstormed during Session 2, drawing all possible causal arrows, and adding intermediary factors to help explain these causal relationships. For example, participants discussed how feelings of inferiority compared to peers led to alcohol-involved sexual violence both directly and indirectly through binge drinking behavior. This activity also provided opportunities for participants to clarify the meaning of certain concepts. For example, participants defined binge drinking as “drinking more than you can handle.” The final connection circle, shown in Supplemental Figure S2, included the factors (n=17) that participants deemed as most important in understanding and influencing the overall system of alcohol-involved sexual violence.

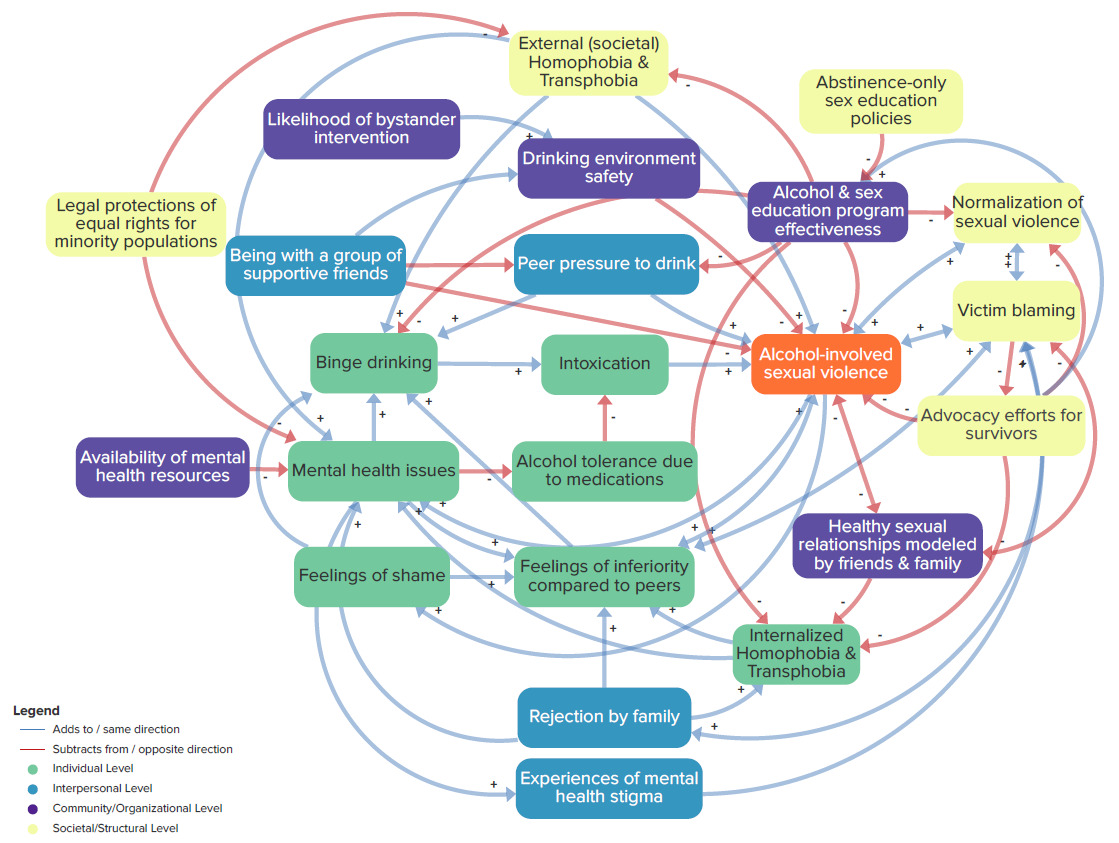

Session 4: Feedback on Causal Loop Diagram and Action Ideas: Facilitators presented a preliminary casual loop diagram developed based on the connection circle from Session 3, including decisions made by the research team (e.g. combining “making victims feel seen” with “advocacy efforts” into one factor: “advocacy efforts for survivors.”). Participants reviewed this preliminary diagram and suggested changes regarding the directionality and type of arrows (i.e., whether they should be positive or negative). In addition to providing feedback on the arrows, participants reviewed the variables in the causal loop diagram and discussed potential changes. Much of this discussion focused on the value of breaking out mental health issues into internalizing and externalizing behaviors; the group ultimately decided to keep this as one factor. The group also added several factors related to the drinking environment. For example, they discussed how being with a group of supportive friends reduced risk of alcohol-involved sexual violence directly, as well as indirectly by decreasing peer pressure to drink and increasing drinking environment safety. Participants also brainstormed ideas for influencing the overall system to reduce alcohol-involved sexual violence. These ideas included increasing the availability of mental health services and legal protections of equal rights for minority populations. The final causal loop diagram, shown in Figure 3, included 22 interdependent factors spanning multiple social ecological levels (e.g., ranging from “binge drinking” on an individual level to “normalization of sexual violence” on a structural level). By viewing the final causal loop diagram on kumu via the following link, one can hover over a variable of interest to more clearly see its connections to other variables: https://kumu.io/mid94/engaging-sgm-with-systems-science#full-cld-figure-3.

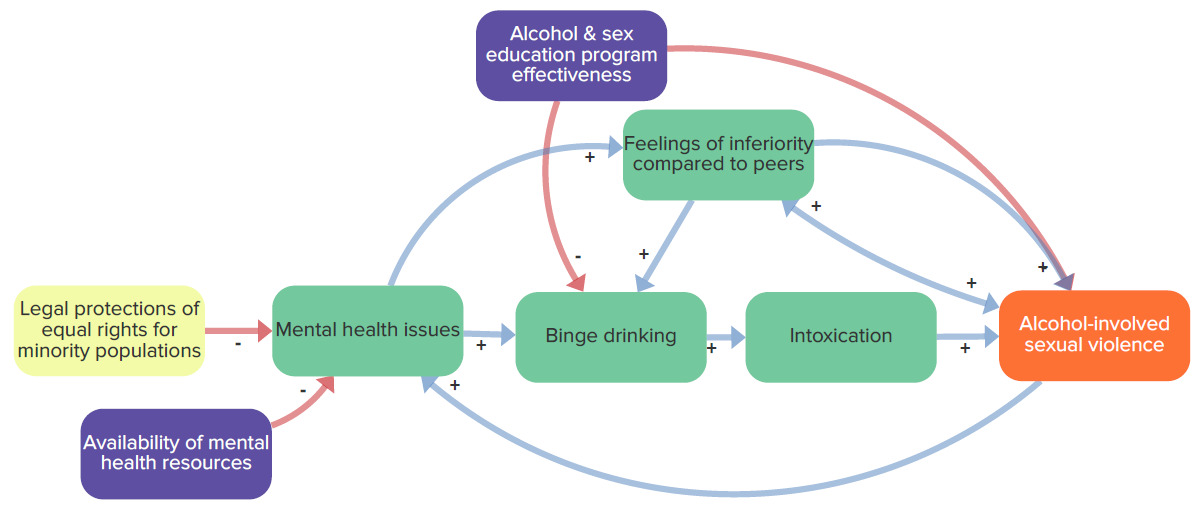

The final causal loop diagram can be used as a tool for examining specific feedback loops influencing alcohol-involved sexual violence. For example, Figure 4 features distinct feedback loops that were particularly salient to participants in that a large portion of our discussion focused on them: 1) increased mental health issues lead to an increase in feelings of inferiority, which leads to increases in alcohol-involved sexual violence, which in turn leads to increased mental health issues, 2) binge drinking leads to intoxication, which leads to increased alcohol involved sexual violence, which in turn leads to increased feelings of inferiority among peers, leading to more binge drinking. Both loops are reinforcing loops because the factors included in them act upon one another to generate a continually increasing pattern.

Figure 5 shows how potential interventions may work to mitigate these reinforcing feedback loops and thus influence risk of alcohol-involved sexual violence. The effectiveness alcohol and sex education programs can reduce alcohol-involved sexual violence both directly and indirectly via reductions in binge drinking. Similarly, the figure shows how legal protections for equal rights for minority populations and availability of mental health resources may reduce alcohol-involved sexual violence by decreasing mental health issues. Both Figures 4 and 5 are also accessible via the kumu link included above.

Participant Feedback Session Feasibility, Acceptability, and Appropriateness

Seven of the eight participants completed the follow-up survey and six provided complete responses on items pertaining to session characteristics. Table 2 summarizes the responses of the six participants with complete data. Their average ratings exceeded our a priori benchmark of 3.75 for session acceptability (4.3; 95% CI: 3.8, 5.0), appropriateness (4.7; 95% CI: 4.3, 5.0), and feasibility (4.7; 95% CI: 4.1, 5.0).

As part of the follow-up survey, participants also provided open-ended feedback, offering recommendations for improving future sessions. These recommendations included shortening session duration, providing unstructured time for participants to get to know each other without facilitator involvement to increase comfort in discussing sensitive issues, and holding brief pre-interviews to confirm that participants were able to engage in each session (e.g., had a laptop, able to turn on camera/audio). With regards to MURAL, participants recommended sharing a MURAL tutorial with participants ahead of time, demonstrating MURAL during sessions, and offering participants an opportunity to practice using it. Participants’ suggestions for increasing recruitment included posting on social media (e.g., Instagram), disseminating information through additional university organizations and faculty members, and offering a bonus payment to participants who attended all four sessions.

DISCUSSION

Pilot testing GMB to identify the optimum sequencing, timing, and modality of activities is important given that the method is highly flexible (Ackermann et al., 2011). This pilot study extends prior work by using validated measures to ascertain the perspectives of SGM college students on GMB implemented in an online setting. Overall, we found implementing GMB using Zoom and MURAL was a feasible, acceptable, and appropriate way of engaging SGM college students to understand mechanisms underlying alcohol-related harms. Structured tasks that prompted participants to think across social-ecological levels and co-create tangible outputs enabled them to come to a consensus on distal factors (e.g., normalization of sexual violence, victim blaming, rejection by family) and their potential causal linkages to more proximal factors (e.g., mental health issues, binge drinking) and the outcome of interest, unveiling potential interventions points on multiple levels (e.g., alcohol and sex education program effectiveness, advocacy efforts for survivors, availability of mental health resources, likelihood of bystander intervention). Although specific to alcohol-involved sexual violence, the findings of this pilot demonstrate the broader usefulness of GMB for identifying multi-level, interdependent causal factors typically neglected by interventions seeking to address alcohol-related harms among SGM populations (Dimova et al., 2022; Kidd et al., 2022). Further evaluation of how the interventions identified could work to influence the system (e.g., how do advocacy efforts for survivors reduce alcohol-involved sexual violence via reduced homophobia/transphobia and mental health issues?) would be needed to ascertain whether the causal loop diagram produced through this pilot can be used to effectively address alcohol-involved sexual violence (Hovmand, 2014).

Similar to other studies, this pilot demonstrated the value of GMB in centering the voices of individuals with lived experience. As noted by Savona et al., who implemented GMB with youth, the method allowed researchers and participants to bridge their perspectives and partner in the co-creation of outputs (connection circles, causal loop diagrams), visualizing complex mental models (Savona et al., 2023). By incorporating the perspectives of individuals with lived experience, GMB can identify causes and effects that might not be otherwise prioritized by researchers or policymakers (Matson et al., 2022). Like Savona et al., we also found that the combination of divergent (e.g., individual brainstorming) and convergent (e.g., connection circle building) activities was useful for addressing potential group power imbalances (i.e., by ensuring those who may have been hesitant to share were able to contribute). The prompts we provided to participants asked them to discuss alcohol-involved sexual violence in a general way, which may have facilitated discussion around a sensitive subject and sharing of important insights extending beyond participants’ own personal experiences.

Limitations and Lessons Learned

The challenges and limitations that we encountered in this pilot can help inform the approach of future studies seeking to engage SGM college students with GMB. We anticipated that conducting this study in an online setting during the summer would facilitate participation since students would largely be free from academic commitments and able to participate from remote locations. However, although we invited 16 participants to attend Session 1, only two attended, despite email reminders. If those who participated in later sessions also participated in Session 1, participants may have selected a harm other than alcohol-involved sexual violence to focus on in Sessions 2-4; this underscores the importance of having a sufficient number of participants for Session 1 in particular. Another recent GMB study found that online formats do not necessarily lead to increased participation (K. K. Brown et al., 2022).

We found that asking participants to refer others and RSVP to sessions were helpful strategies for increasing attendance. Furthermore, calling participants with reminders allowed us to verify the identity of participants, which was particularly important given the number of invalid screener responses we received, a challenge increasingly experienced by other studies employing online surveys (Goodrich et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2022). In their post-session feedback, participants noted that compensation was an important motivator for their attendance. Given this, we may have increased our retention by offering a bonus for attending all four sessions. In addition, we may have benefitted from collaborating more closely with the undergraduate SGM college students who assisted with practice sessions. Although these students were instrumental in providing feedback on our session facilitation, we did not seek their advice for improving recruitment and retention. This is a major area for improvement, as partnering with individuals with lived experience through all phases of the research process is a key participatory research principle (Israel et al., 1998). Finally, this study may have benefited by following best practices for engaging participants online, including creating a study webpage and using a multipronged online recruitment strategy (King et al., 2014). Future studies may benefit from consulting the comprehensive checklist for implementing research in online settings developed by Wilkerson et al. (Wilkerson et al., 2014).

This study’s small sample size limits its generalizability, especially the extent to which it is representative of all SGM college student identities. Although our study successfully engaged individuals with a range of sexual orientations and gender identities, no cisgender men participated in this study, which is a limitation as individuals with these identities likely have unique experiences with alcohol-related harms. Additionally, few individuals with minoritized racial and ethnic identities participated. Future systems science studies addressing alcohol-related inequities among SGM college students would benefit from an intersectional lens that considers the vantage points of those experiencing multiple forms of marginalization. This includes students with disabilities as these students face significant gaps in the extent to which alcohol and sexual violence prevention resources meet their needs (Chugani et al., 2021). Group model building typically engages small groups of collaborators; however, researchers can incorporate diverse perspectives by conducting sessions with multiple cohorts of collaborators (Mair et al., 2024).

MURAL and Zoom facilitated participation from participants who were off campus for the summer. However, although we screened for participants with access to computers with audio/visual capabilities, we found that some participants still attended sessions on their phones or were unable to turn on their microphones/cameras, making it hard for them to participate in MURAL activities. In instances in which participants struggled to participate, having an additional facilitator present to document feedback from the Zoom chat was helpful. As one participant suggested, conducting brief pre-screening interviews may have helped ensure that participants had the necessary computer set-up to participate in MURAL activities. Use of these online methods can enable researchers to engage a geographically diverse group of participants; however, our approach excluded individuals without access to technology or a safe, stable space from which to participate. More work is needed to ensure these methods can engage SGM college students in these circumstances.

Our final causal loop diagram, which included 22 factors, illustrates the interdependence among the factors in this complex system. While the diagram useful for “zooming in” on specific subsets of factors to examine dynamic relationships in the context of this larger system, it is challenging to interpret all the dynamic relationships (i.e., loops) given the high level of complexity. Boundary setting (i.e., deciding which variables should be included or excluded) is a common challenge in building complex systems models (Langellier et al., 2019). Incorporating more ranking activities throughout our sessions may have resulted in a more parsimonious diagram. For example, Lemke et al. included a step in their process for collaborators to vote on which factors were within their ability to influence vs. not within their ability to influence (Lemke et al., 2022).

CONCLUSIONS

Online GMB is a feasible, acceptable, and appropriate approach for engaging SGM college students to identify the mechanisms underlying alcohol-related harms in a collaborative manner. Given the persistent and complex nature of substance use and alcohol inequities among SGM populations, novel approaches are needed to understand the complex and interdependent causal relationships underlying alcohol-related harms in this population. This pilot demonstrates that GMB has strong promise for better understanding such relationships and identifying potential interventions that modify them.