Introduction

Poverty assistance programs like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) often focus on correcting a perceived lack of discipline among “the poor.” Such programs temporarily relieve acute financial stress but do little to end the root causes of persistent poverty (Soss et al., 2011). Traditional financial literacy interventions that focus on individual behavior change have little impact on actual financial circumstances of lower-income families (Fernandes et al., 2014). These interventions reinforce a stereotypical “culture of poverty” that blames people for their economic status because they have “bad values” that drive unwise personal choices (Frameworks Institute, 2019).

The Prosperity Agenda (TPA) is a nonprofit organization whose human-centered design (HCD) process runs counter to prevailing approaches that are anchored in the assumptions that families in poverty make bad financial decisions, don’t know how to save money, and are responsible for their own fate (Fraser & Gordon, 1994; Jacobson et al., 2009). From 2016 to 2019, with support from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, TPA collaborated with the Washington State Department of Commerce (Commerce), who manage TANF programs, to develop and implement a new program to encourage two-generational savings among families receiving social welfare assistance. This paper summarizes TPA’s utilization of HCD principles and participatory research (PR) methods in the creation of this intervention.

Methods

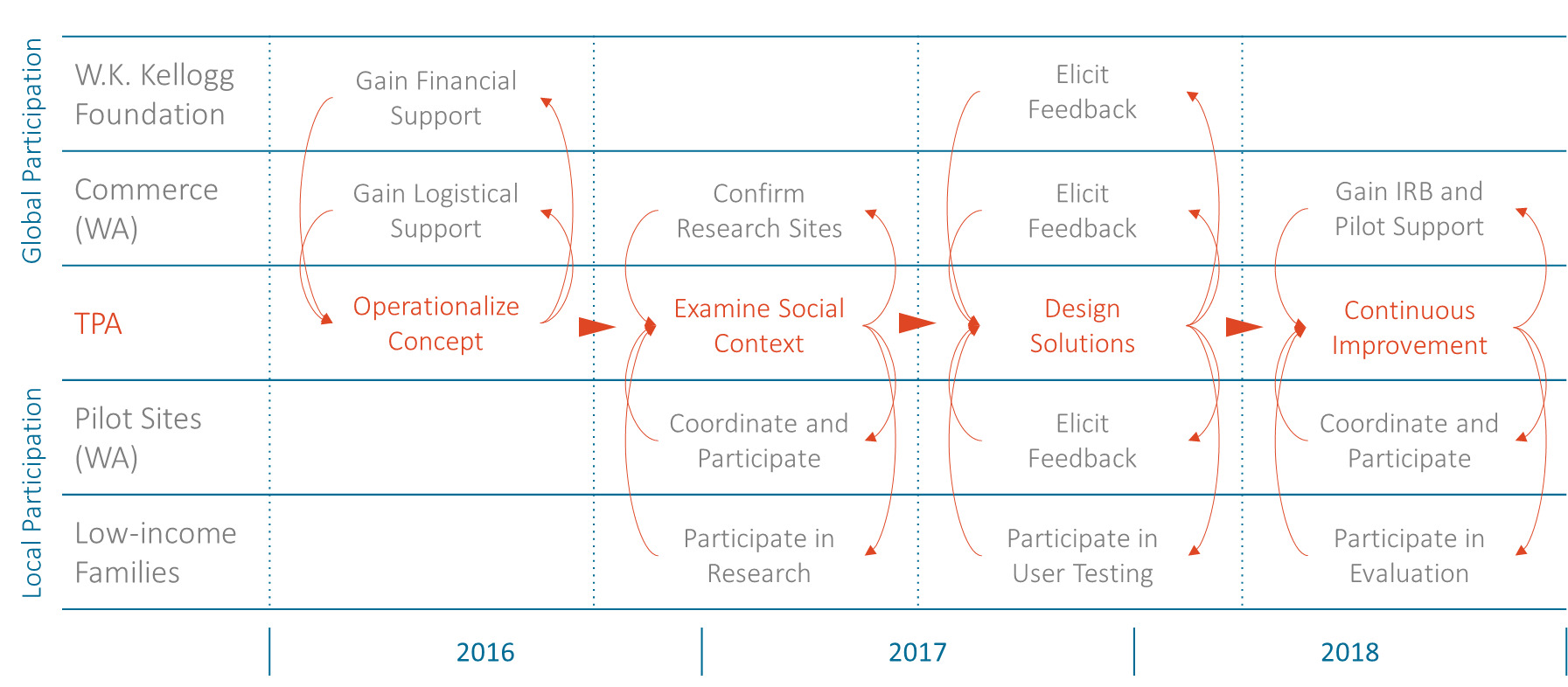

Bergold and Thomas (2012) described PR as the involvement of any groups of people who are not professional researchers. The Savings Initiative combined PR with HCD and systems thinking to cultivate a shift from the status quo (Figure 1). Both HCD and PR focus on how to generate innovative solutions to social problems with a commitment to uphold dignity and respect for marginalized populations (Björling & Rose, 2019; Kia-Keating et al., 2017). Poverty in particular contains many challenging and interdependent factors that require a systems approach to improve impact (Frameworks Institute, 2019). To transform a system, one must transform the relationships between people who make up the system (Kania et al., 2018). TPA acted as third-party facilitators, designers, and evaluators to cultivate the conditions for collaboration and participation across stakeholders, while assessing and documenting progress towards a community-based solution (González, 2019).

Results

Operationalize Concept: TPA partnered with Commerce to develop an intervention that would outperform traditional financial literacy programs and meet families’ needs. Commerce provided in-kind support like access to clients, assistance with Washington State Institutions Review Board (IRB), and $20,000 for pilot site stipends. The Kellogg Foundation provided financial resources for TPA to perform research, design, testing, and program refinement. Success for this initiative was guided by one key question: How might we use a two-generation approach to improve financial resilience and to strengthen savings behaviors of parents in social welfare programs?

Examine Social Context: To inform the design, TPA conducted a robust qualitative inquiry. TPA and Commerce identified four rural and urban contractors in Washington State. TPA and the contractors developed an interview protocol and conducted in-person interviews, focus groups, and observations to gather first-hand parent information about savings barriers, practices, behaviors, and goals. TPA interviewed program staff to understand the constraints of introducing new programs. TPA interviewed 40 parents receiving TANF, 26 contractor staff (case managers, program managers, and program directors), and 7 staff from Commerce.

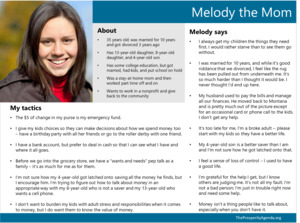

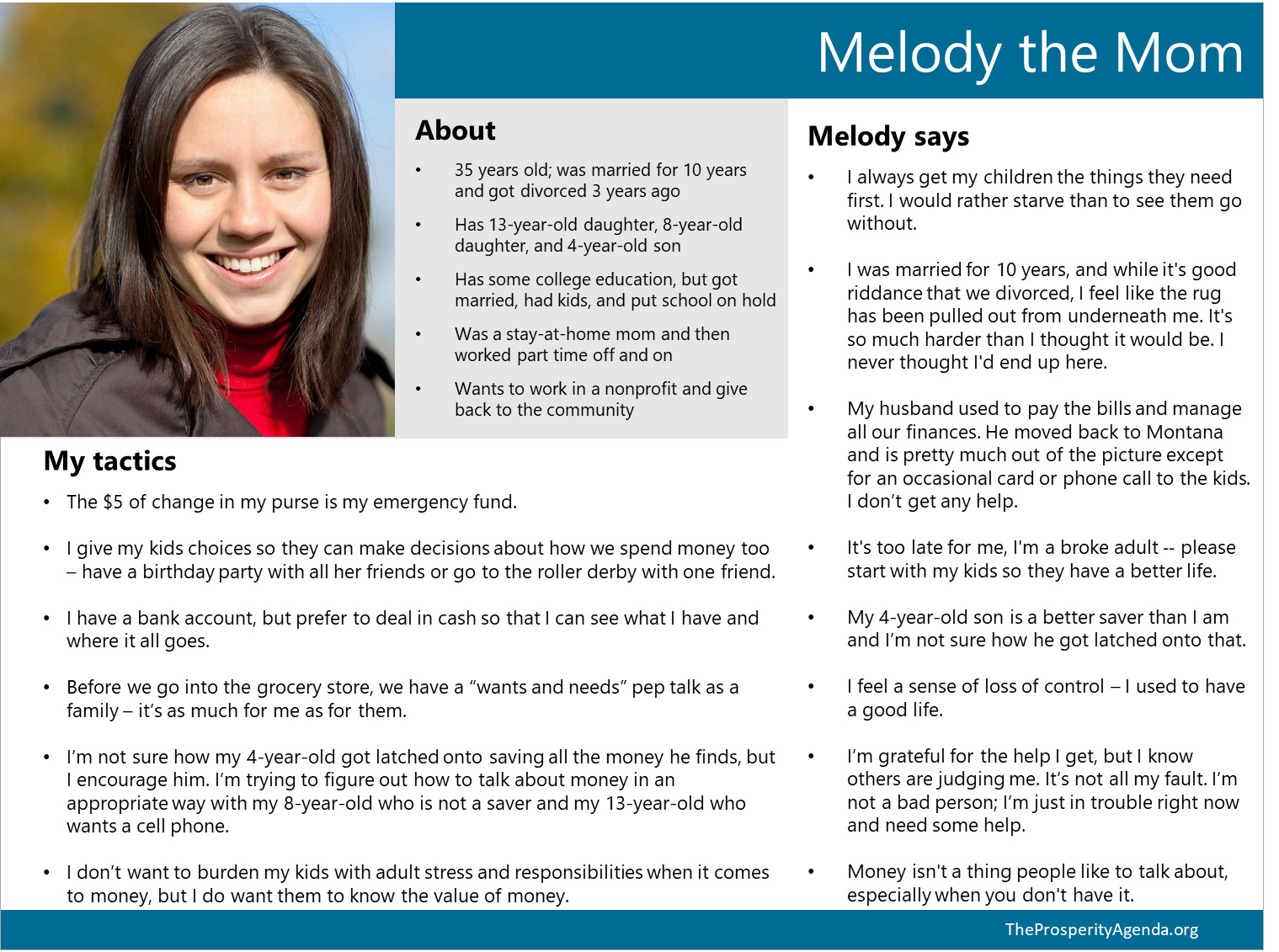

Immersion in the lived experience of an intervention’s intended beneficiaries is essential to HCD (Mulgan, 2006). The research phase yielded significant insights about how families save, spend, and discuss finances with their children. TPA analyzed the qualitative content by categorizing commonalities and identifying overarching themes. Insights were used to develop “Personas” and “Causality Maps.” TPA built three personas: one case manager and two TANF participants (Figure 2). Personas are not summaries of the research. They communicate key opportunities and challenges that emerged from research.

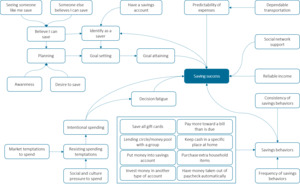

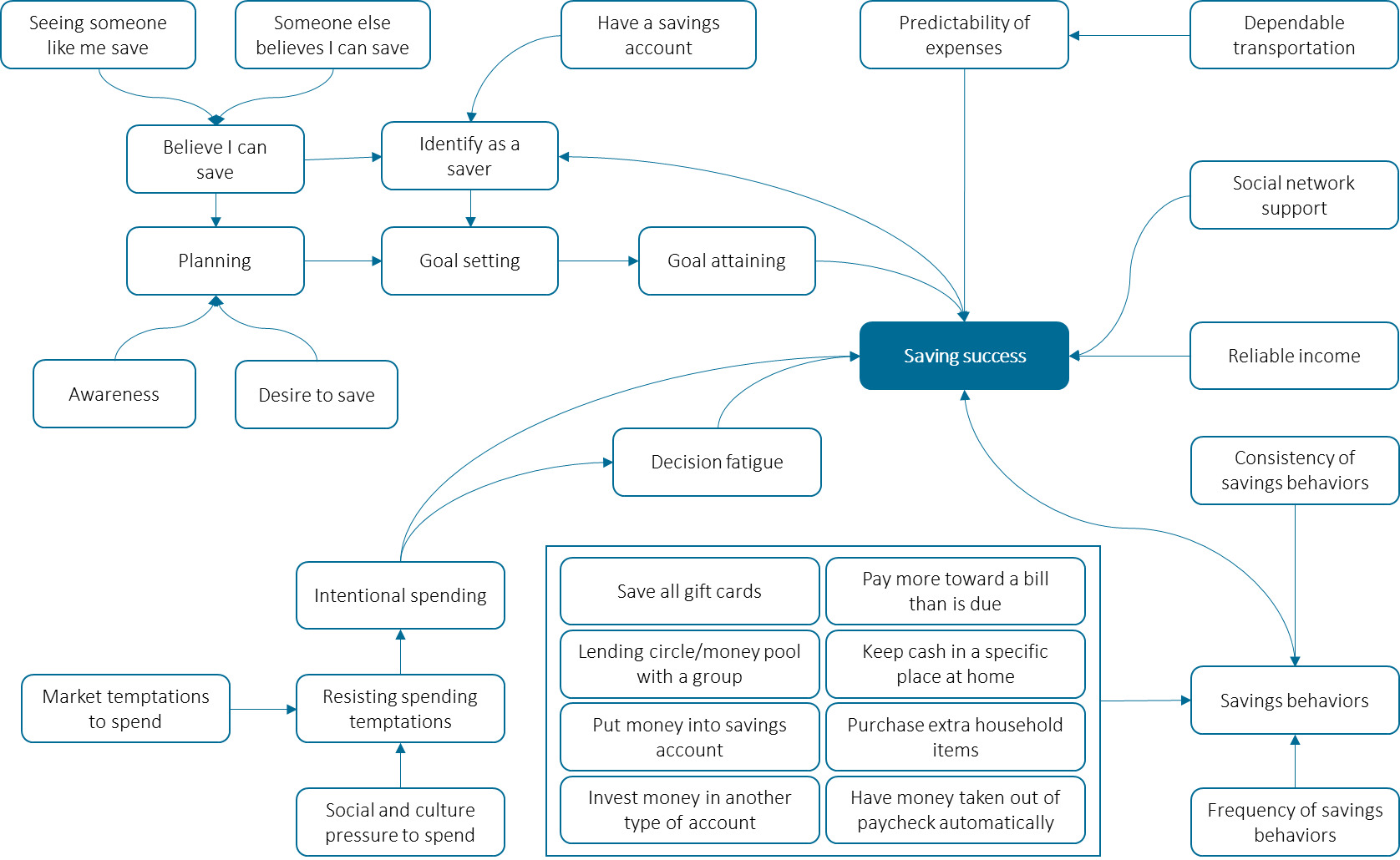

TPA developed two causality maps to communicate additional research insights from participants. The first causality map (Figure 3) shows how TANF program parents described different levers that impact their savings success. The second causality map captured how parents and children influenced each other’s savings behaviors. Understanding these causal mechanisms allowed TPA to set priorities, make informed decisions, and hypothesize short- and long-term outcomes for the evaluation.

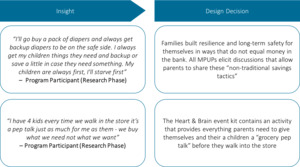

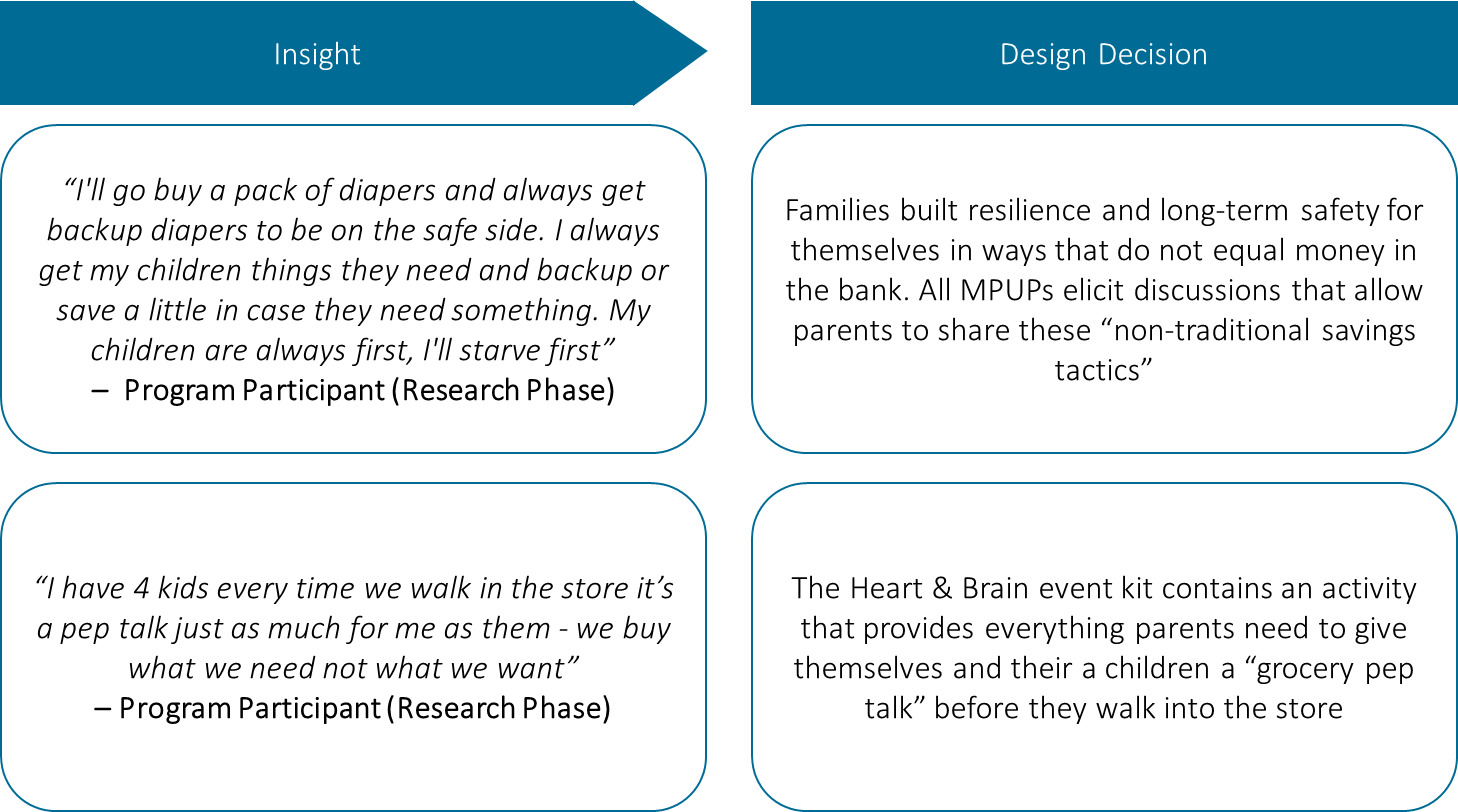

Design: The design team consisted of eight individuals: one career coach who was previously enrolled in TANF, three design consultants, and four TPA staff. They engaged in six four-hour design sessions and reviewed the “how might we” question, personas, and causality maps to gain a mutual understanding of the challenge. Especially when the team engaged with the personas and causality maps, which are direct reflections of problems and successes described by impacted families, they surfaced three main “design criteria” that drove the development of potential solutions: 1) impacted families utilize a wide range of non-traditional savings tactics, like paying more toward a bill than is due; 2) social and cultural pressures to spend money add to decision fatigue; and 3) connecting with others and identifying as a saver increases the likelihood of achieving (financial) goals.

Building on these principles, the design team brainstormed and clustered ideas on sticky notes. These clusters yielded multiple possible prototypes. One idea stood out as having the highest possible feasibility and impact: easy-to-implement event kits that help staff facilitate conversations around money. TPA named these event kits Money Powerup Packs (MPUPs). The career coach and TPA collaborated with TANF parents to improve the initial concept, refine measurement tools, and define what success was. One participant reported that the post-event survey provided a way to be truthful about non-traditional savings tactics.

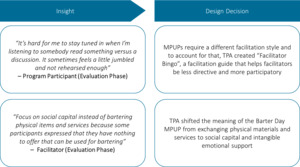

Continuous Development: Four contractors from the research phase tested four MPUPs for four months. TPA solicited feedback through surveys and phone calls with the facilitators. To create a valuable experience for participants, MPUPs have to work for facilitators. Facilitators that elevated the participants’ voice provided important information about the strengths and challenges of the materials, structure of the events, and value of event activities. Informed by the first round of testing, TPA designed four additional MPUPs and improved existing MPUPs by adding content, creating electronic formats, enhancing instructions, and providing more guidance on facilitating event activities. Because TANF recipients are a protected class, including their perspective directly was not possible until the IRB approved the evaluation study. TPA adopted a mixed-methods evaluation design and connected evaluation questions with projected outcomes, measurement tools, frequency of data collection, and data analysis methods.

Facilitators had the power to decide how to implement MPUPs. They decided to change or expand the activities, or even alter the meaning and intent of each event. TPA conducted more than 56 check-in calls to emphasize that facilitators were co-researchers and designers throughout the process. For many facilitators, this was a complete shift from the norm, where they are often directed to complete tasks but not invited to contribute to the overall vision or efficacy. Facilitators employed at organizations that are less hierarchical generally felt more comfortable with ambiguity and made autonomous decisions to permanently change the course of MPUPs.

Participants had the power to directly influence decisions that drove MPUP refinements. TPA responded to each and every suggestion made by participants in accordance with the design criteria from the research phase. For participants to voice their opinion about the events, facilitators were coached to create a safe space and remind participants that their feedback will be used to improve MPUPs for future participants. An external evaluator from the University of Washington confirmed that “the safe space provided participants an opportunity to share their feelings in a non-judgmental environment.”

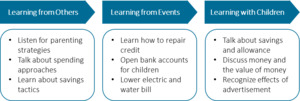

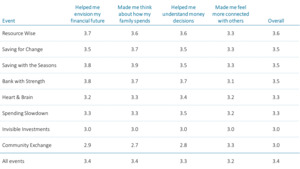

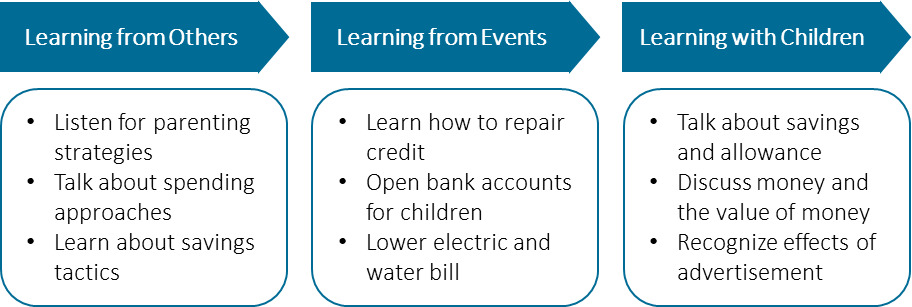

Altogether, 330 TANF-receiving parents participated in the MPUP evaluation. TPA gathered their feedback through baseline, outcome, and post-event surveys. TPA also observed multiple MPUP events, interviewed 6 facilitators, and conducted 11 focus groups. The external evaluator confirmed that participants described MPUPs as supportive, non-judgmental environments in which they could directly participate in learning about money and savings. Figure 7 shows how participants learned from each other, from events, and with their children. Figure 8 demonstrates that participants envisioned their financial future, reflected on family financial behavior and financial decision-making, and felt socially connected (scale equates 1 with “disagree” and 4 with “agree”).

MPUPs provide sufficient space for participants to connect with one another and build relationships. This unique feature lets participants build mutual trust, share vulnerably, and offer each other guidance and insight.

Limitations

Engaging diverse stakeholder groups in ambiguous research and design processes surfaced multiple challenges: 1) IRB requirements curbed TPA’s ability to be flexible and fully share decision-making power with impacted families throughout the process; 2) mandatory participation from both the pilot sites and program participants limited TPA’s capacity to learn about MPUPs in a natural and completely voluntary setting; and 3) building relationships with Commerce took over six months and caused confusion about IRB requirements, delaying project timelines and demanding valuable resources.

Implications for Practice

Despite various limitations, TPA learned three major lessons along the way that matured their HCD process and PR methods significantly: 1) careful partner selection is the most critical step in fostering the conditions for collaboration across stakeholders. Organizations who promote autonomy among frontline staff, believe in the resourcefulness of low-income families, and consider themselves innovation engines with prime testing grounds should participate in working groups alongside impacted families and hold equal decision-making power to shape and execute a successful research phase; 2) in addition to adapting to the availability of impacted families, design sessions and unstructured ideation sessions should occur more frequently to include more underrepresented perspectives, which are critical in the development of social innovations using participatory methods; and 3) the expertise from former research and design participants who represent the larger system should be tapped to further refine solutions, detect anticipated and emergent outcomes, and inform strategies to scale impact.

Conclusion

TPA’s HCD approach combined with PR methods and systems thinking yielded innovative event kits that facilitators used to initiate meaningful conversations around money. Evaluation results confirmed that by partnering with low-income families and event facilitators, TPA was able to design pragmatic solutions that helped families build financial resilience. Organizations like TPA are uniquely positioned to share power with marginalized families while, at the same time, earning trust from decision-makers to continue pursuing processes that overcome disciplinary mindsets and instead promote dignity, respect, and prosperity for all.