This article describes two projects that utilized Charette processes to build community-academic partnerships. The first Charrette project was conducted in 2015 with the goal of bringing together community and academic partners to write a grant proposal for research in health disparities. With a separate group of participants, the second Charrette project in 2018 aimed to establish a Community Advisory Board (CAB), and develop capacity and skills among board members to conduct patient-centered outcomes research. This article draws upon lessons learned from these experiences. Our goal is to describe how researchers and community stakeholders can use Charrette processes to effectively build partnerships and stimulate successful community-based participatory research (CBPR).

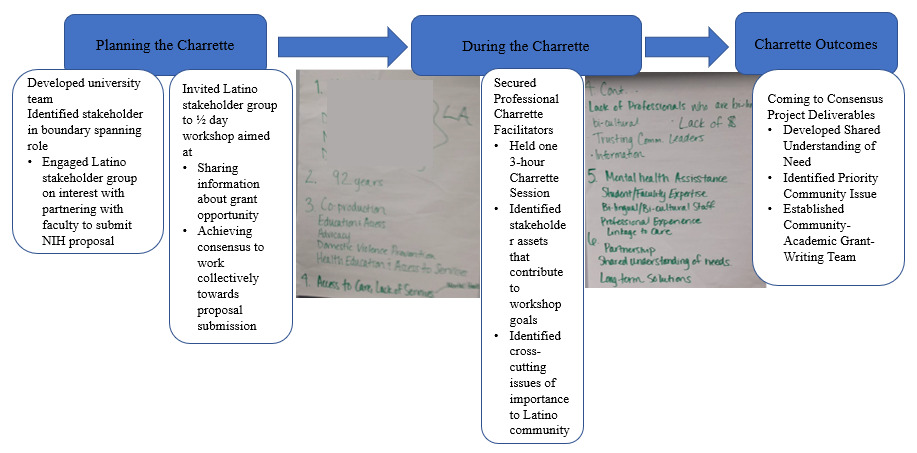

In 2015, faculty researchers from a regional university in southeastern North Carolina identified a funding opportunity that supported the development of community-academic partnerships that would focus on reducing health disparities using CBPR. They secured funding to host a one-day Charrette workshop, bringing together researchers and members of a local collaborative, the Latino stakeholder group. The objectives of the workshop were to establish and/or enhance existing community-academic partnerships, identify community-driven research priorities, and lay a foundation to develop long-term collaborative CBPR research agendas.

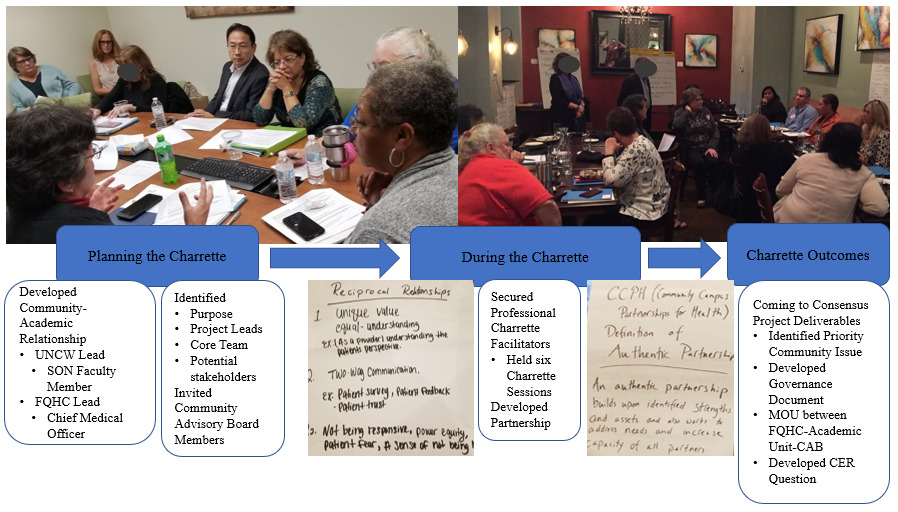

The 2018 Charrette was undertaken as part of a funded project that established a research partnership between a federally qualified health center (FQHC), and a regional university in North Carolina, utilizing CBPR methodology. FQHCs are safety net providers, funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), that provide healthcare services to a community’s most vulnerable populations – those who are uninsured, underinsured, and/or are transient (e.g. homeless, migrant workers). Developing and formalizing this research partnership, including the establishment of a CAB, was made possible with funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

Using 8 characteristics of Charrette derived from a meta-review of federally funded Charrettes in Scotland (Kennedy, 2017), this paper aims to guide stakeholders in how to effectively plan for incorporating Charrette into their partnership process. We also have included lessons learned and the challenges that arose from our two practical Charrette cases. While traditional Charrettes are characterized by short-term, intensive interactive formats, the Charrette is highly customizable, making it an ideal process to incorporate into CBPR research. Both Charrette experiences proved instrumental in achieving the outcomes of each experience, even though both projects differed in purpose, membership, and scope. The experiences and lessons learned in both projects highlight the strengths and challenges in developing community-academic partnerships.

Background

Originating in the design field, the term “Charrette” stems from the French word, “little cart,” referring to the method by which architecture students submitted their work for grading. Students would rush to complete their work before the cart arrived; thus, the term “Charrette” implies an urgency. This sense of urgency came to characterize the modern Charrette in which participants meet intensively to discuss and inform facilitators about a project or goal (Kotval & Mullin, 2014). The Charrette process remains connected to its origins as an architectural process; it is frequently used to inform designers about community needs for a specific space. Generally, models provided by the National Charrette Association are geared toward assisting architects, city planners, and designers in gathering community input (Lennertz & Lutzenhiser, 2006).

Various definitions of Charrette emphasize the importance of stakeholder involvement, immediate feedback, and development of a testable plan beyond the brainstorming stages (Kotval & Mullin, 2014; Lennertz & Lutzenhiser, 2006). A conventional Charrette consists of short, intense collaborative sessions between designers and community stakeholders, characterized by rapid progression toward a plan and immediate feedback loops (Kennedy, 2017). The National Charrette Association defines the Charrette process specifically as “a collaborative design and planning workshop that occurs over four to seven consecutive days…and includes all affected stakeholders at critical decision-making points” (Lennertz & Lutzenhiser, 2006, p. 3). Kotval and Mullin further describe the Charrette as “a process of collaboration, intense dialogue and deliberation between participants to promote understanding and facilitate planning activity” (Kotval & Mullin, 2014, p. 494). Although the specific steps and activities vary based on the facilitators, stakeholders, and objectives of the project, most Charrettes follow a structure aimed at defining the design goals and issues, exploring proposals, and refining those to identify preferred solutions (Girling, 2006).

The Charrette process is not limited by scope of design area and has been used effectively to address both micro- and mezzo- level community challenges. One example of a mezzo-level Charrette was conducted by a team in the Boston area. Designers utilized Charrette to identify the best way to mitigate traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) in a developing near-highway neighborhood. Designers sought community input to help identify the best ways to incorporate TRAP mitigation efforts into the neighborhood (Brugge et al., 2015). The Charrette participants not only proposed several creative solutions, but also prioritized TRAP mitigation beyond the designer’s expectations, a conclusion that would not have been possible without the utilization of the Charrette process (Brugge et al., 2015).

In conducting a Charrette with university and community stakeholders, researchers planned a series of workshops over a semester-long timeline (Portschy, 2015). The workshop goals were to establish design criteria to address “programmatic requirements, building character and spatial experience” and determine the project’s budget (Portschy, 2015, p. 6). These Charrette workshops successfully incorporated participant input into the redesign of the university’s library space and benefited the community by providing access to design expertise as well as a platform to explore creative solutions. The university students benefited by gaining experience in Charrette-facilitated design processes (Portschy, 2015). As this study illustrates, the Charrette may vary in scope, format, and duration, but retains a key emphasis on community engagement and input during the design process.

Occasionally, feedback collected through the Charrette process prompts the need for significant change to the original project. The collaborative nature of the Charrette provides researchers with unexpected information about the community, which helps stakeholders make informed decisions about current and future projects. In one such example, researchers used the Charrette to address community concerns regarding plans to increase the residential high-rise capacity in a Toronto neighborhood (Poppe & Young, 2015). To the researchers’ surprise, the Charrette participants vehemently rejected the plan to build additional high-rises. Instead, participants reframed “growing” the neighborhood as projects that increased quality, beautification, or property values. While the Charrette did not lead to innovative ways to increase and better integrate high-density towers, researchers concluded that the Charrette highlighted how a single neighborhood could impact city planning (Poppe & Young, 2015).

Another Charrette with unexpected outcomes was conducted in Oregon by local partners and residents to redesign a community park (Patton-López et al., 2015). Working with the city planning authority, community partners conducted a Charrette during which residents identified the need for new types of park equipment with the aim of increasing youth physical activity level. The city planner drew on feedback gathered during the Charrette to design and install the new equipment. Researchers also assessed youth activity levels before and after the park equipment was installed. The Charrette stakeholders met again after the installation to discuss the rational outcomes, challenges, and successes of the park redesign. While the research team did not see a difference in youth activity as expected, they concluded that the Charrette process still produced beneficial outcomes for the community. Specifically, the process laid the groundwork for future youth health initiatives by “building on existing community strengths, increasing civic engagement, and strengthening community relationships” (Patton-López et al., 2015, p. s104).

Charrette in Community-Based Participatory Research

Recognizing the Charrette’s ability to promote community engagement and partnership, researchers have adopted the Charrette as a tool to develop capacity among community stakeholders (Howard & Somerville, 2014). A study of Charrette processes found that participants who were treated as co-designers, as opposed to simply consultants, demonstrated increased engagement in the process. Additionally, involvement in pre- and post- Charrette decision-making increased participation and enthusiasm (Howard & Somerville, 2014). Although the use of Charrette in CBPR is still an emerging concept in the literature, a few key studies demonstrate that Charrette is a promising tool for CBPR researchers and stakeholders.

In 2010, the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill adapted the Charrette for innovative use in CBPR (Samuel et al., 2018). In the research context, Charrette is defined as, “a collaborative planning process that harnesses the talents and energies of all interested parties to create and support a feasible plan that represents transformative community change. The goal is to accelerate research while providing technical assistance to enhance the design, implementation and dissemination of community-engaged research” (“Charrettes,” 2019, para. 2). In general, research suggests that Charrettes effectively increase participation of multiple stakeholders and promote applied, creative problem-solving (Hughes, 2017).

In 2018, facilitators from UNC conducted CBPR Charrettes with participants from the Cancer Health Accountability for Managing Pain and Symptoms (CHAMPS) Study (Samuel et al., 2018). The facilitators worked with 14 participants interested in studying the effects of race on differences in treatment and symptoms among breast cancer patients. Participants included representatives from several academic, medical, and community organizations. Because of the varied interests, backgrounds, and expertise of the different participants, the Charrette focused on “identifying and addressing community, academic, and medical partner concerns regarding their new research partnership, clarifying roles and responsibilities, and planning for CHAMPS implementation” (Samuel et al., 2018, p. 91). The Charrette included three hours of in-person development, including a “Charrette Session Overview” to define the facilitators’ role, a “Group Resume” activity to identify group expertise, a “Key Questions” discussion to foster “transparency, accountability, and collective problem solving through open discussion of partner concerns and challenges,” and a “Post-Charrette Evaluation” (Samuel et al., 2018, p. 94). Following the Charrette process, the group showed an increased awareness in group strengths, engagement in the CHAMPS research process, “synergy among partners,” and a renewed “commitment to a shared mission” (Samuel et al., 2018, p. 95). The Charrette also highlighted challenges to the group, including concerns about the academic researchers’ unrealistic expectations of the community members. Despite a broad range of interests and expertise among members, the Charrette process provided an opportunity to address potential challenges and build group cohesion (Samuel et al., 2018).

A study to assess the function of a Kentucky university-based emergency department found that Charrettes offered a meaningful educational exchange between community members and researchers; through the Charrette process, participants gained an increased sensitivity to the value of evidence-based decision-making (Fay, et al., 2017). A separate study examined the effectiveness of Charrettes in post-disaster recovery in Japan. Researchers found that the stakeholder engagement fostered by the Charrettes resulted in faster identification of necessary training and resources, leading to greater cohesion in disaster recovery efforts (Zhang, Mao, & Zhang, 2015).

Overall, Charrettes have been shown to be effective tools for building intergroup collaboration toward a specific objective, even when groups have different backgrounds and expertise (Wishkoski et al., 2019). Charrettes are most effective when participants are involved throughout the decision-making process, and are approached as true collaborators, as opposed to focus group members or consultants, making CBPR and the Charrette process highly compatible with one another (Hughes, 2017; Samuel et al., 2018). Although the outlook for Charrette as an effective CBPR tool is encouraging, only a few articles have emerged that utilize the Charrette process as a capacity-building tool for groups of community stakeholders, nor could we find articles that presented different conventional and non-conventional Charrette processes in a comparative context. This paucity of scholarship motivates our documentation of the utilization of Charrette in two CBPR projects (see boxed Case Examples) while informing interested stakeholders who might consider using the Charrette process, including professional CBPR Charrette facilitators from UNC, to advance their work.

Case Examples

Evaluation Framework

Kennedy identified eight characteristics derived from a meta-synthesis of 46 Charrette reports conducted in Scotland between 2011 and 2016 (Kennedy, 2017). Using a novel conceptual framework to evaluate these cases, researchers derived the characteristics that defined the Charettes they examined.

Although a Charrette has a predetermined format and traditional attributes concerning length, structure, cost, etc., Kennedy et al.'s meta-synthesis suggests that the characteristics of a project can be adapted to meet the goal of the participants and still be classified as a Charrette. We adopted Kennedy’s Charrette characteristics to guide both projects described here. The two case examples serve as context for evaluating the use of the Charrette process in community-academic partnerships, using these characteristics.

Charrette Objectives

Charrette projects have explicit shared objectives about the nature, goals, and future plans for the partnership. There are several ways these objectives may be expressed. Common goals for Charrettes have included assessments of the community’s needs, assets, and opportunities. A Charrette project may also include a vision statement and an explanation of the long-term goals of the partnership. In lieu of a vision statement, Charrette participants may instead develop a framework or master plan specific to their project which serves as a comprehensive roadmap to guide more detailed action. Charrettes may also produce documents such as a Potential Action document, which identifies areas in need of more research, or a Deliverability Work document, which assesses the feasibility and relevance of new projects (Kennedy, 2017). In the Latino stakeholder group Charrette, the objective was to identify an issue and draft a grant proposal. In the second case, the Charrette was intended to build partnership and capacity among members and establish goals which were exemplified in the production of governance documents written by the CAB. CBPR researchers and project leaders need to consider what they want to achieve from a Charrette and how those achievements will be defined and codified, which will then inform choices about other characteristics.

Charrette Mechanisms

Charrettes are based on principles of consistent community participation throughout the process, and as such must also consider how the Charrette’s goals, vision, plan, progress, and outcomes are communicated to the community outside the Charrette session itself. Charrette communication can take many forms, including written materials, meetings, presentations, networking, pre-Charrette workshops, group activities, etc. CBPR researchers also need to consider how they collect information from the community. This may include indirect feedback like social media, questionnaires, and observations, or in-depth feedback such as interviews and group discussions. Public presentations, focused group discussions, and workshops are frequently used throughout the Charrette process “to inform, share perspectives and gather feedback in response to developments through group discussion or scenario planning sessions (Kennedy, 2017, p. 110).” In the Latino stakeholder group case, the research team used their existing network of contacts to connect with the Latino stakeholder group and recruit participants for the Charrette. To recruit members for the Community Advisory Board in the FQHC case, the Core Project Team utilized targeted recruitment via partner contacts as well as a written information brochure. Regardless of the specific mechanisms used, the Charrette emphasizes information sharing and feedback between researchers and the community.

Cost

CBPR researchers and project leaders aiming to use Charrette in their work will need to consider the direct and indirect costs of conducting a Charrette. Kennedy found that 83% of the reviewed Charrettes fell within 1 standard deviation of £18, 660 (~$24,140). It should be noted that these estimates were sourced from design Charrettes, which differ in their cost structure from CBPR Charrettes in terms of consultancy, technology use, and required expertise. Both projects featured in this paper utilized professional Charette facilitators from UNC Chapel Hill. They proved to be an invaluable investment, not only for their expertise in conducting and evaluating Charrettes with CBPR groups, but also as a neutral party to help participants develop their collective identity and values, and for researchers and project leaders to focus on being true collaborators. While researchers can conduct their own Charrette, they must be aware that power differentials may exist between facilitating and non-facilitating group members. Working with third party facilitators in these two cases was instrumental in minimizing such power differentials and was worth the additional associated costs.

Researchers and project leaders will also want to consider associative costs when designing their Charrette. The venue and meeting characteristics affect the comfort and productivity of the participants; thus, costs may be incurred in providing space and catering. Technology use, printed materials, and miscellaneous supplies will need to be budgeted for as well. Additionally, researchers must be sensitive to compensation needs for groups who commit several hours to participate in a Charrette. Costs may need to cover transportation, childcare, or elder care to alleviate barriers to participation. For the Latino stakeholder group project, the Charrette was conducted in a three-hour session in the afternoon. The space was provided free of charge, and food costs were minimal. Attendees were not compensated for their time or travel. In the FQHC case, member availability dictated that meetings occur on weekday evenings. Thus, researchers and project leaders shifted funds to provide dinner during the meetings. Doing so not only encouraged willingness to participate during an unusual timeframe, but had the unexpected benefit of building camaraderie among members during a shared meal.

Duration and Format

Traditional Charrettes are conducted intensively over a few hours or days. Short time periods enhance the engagement, as well as the participants’ focus, ability, and willingness to participate. However, collaborative Charrettes have also been structured to meet periodically over the course of a few months (Kennedy, 2017). Though such a design allows time for supplemental work and research to take place between sessions, it may present challenges for sustained participation. The Latino stakeholder group Charrette took place over one intensive day, and Charrette facilitators worked with the group the entire time. When working with the FQHC, Charrette facilitators worked with the CAB during their monthly meetings over six months. Project co-leads and CAB members collected supplemental data and consulted with Charrette facilitators outside regular meetings. When deciding upon the duration and format of a Charrette, project leaders should consider the ability of participants to fully engage in the Charrette, as well as the willingness and capability of participants to complete supplemental work (towards meeting project objectives) outside of the Charrette.

Participatory Access

While most Charrette sessions are public events, a few have been conducted by invitation only. In the case of the Latino stakeholder group Charrette, all stakeholders were queried about their interest; 15 members registered to attend. Although the FQHC Charrettes were intended to help the CAB build capacity, the CAB meetings were open to the public and inclusive participation was encouraged. Although Charrettes can be conducted privately, CBPR aims to involve the broader community in the research process. Thus, researchers and project leaders should carefully consider and clearly articulate reasons for choosing a private Charrette over a public one.

Applicant Structure

Kennedy (2017) finds that Charrette structures fall into four broad categories: Charrettes initiated by the local government or planning authority; joint applications between the local planning authority and another organization; applications from multiple government organizations; or independent, non-government-supported organizations. Most community-led Charrettes would adopt the latter structure. In these two case examples, the Charrettes were initiated by a non-government, community-academic partnership. Regardless of local government involvement, successful CBPR Charrettes will consistently evaluate which stakeholder voices are present and which are needed in order to provide a comprehensive perspective of the issues facing the target community.

Study Boundary

A Charrette’s study boundary is commonly understood as the geographical area the Charrette seeks to evaluate. In a community-based Charrette, the study boundary could consist of the surrounding community or population. Again, Charrette study boundaries can vary widely from a single building or community center to an entire city or region. The Charrette conducted with the Latino stakeholder group focused on issues within the Latino community in Southeast North Carolina. The FQHC Charrette’s study boundary was defined by the FQHC’s patient population, which included neighborhoods surrounding the clinic and the nearby downtown district. Researchers and project leaders will want to consider who they aim to impact with their Charrette initiative and adjust the scope of their research to reflect the target.

Planning Role

The Charrette’s planning role can be understood as the impact that the outcomes of the Charrette intend to have on the broader planning strategy in the area (Kennedy, 2017). Put simply, the planning role delineates how the project team (researchers and community leaders) will use the information, feedback, and ideas developed by participants during the Charrette. Kennedy found that most Charrettes did not have a funding-related obligation to incorporate the Charrette feedback into a broader local or federal strategy, however many Charrette publications expressed the intent to do so (Kennedy, 2017). In a CBPR Charrette, the desired output of the Charrette extends beyond feedback to produce a collaborative initiative for implementation or further study. In this context, researchers or project leaders may understand the planning role by considering how the results of the Charrette will be utilized beyond the Charrette session. In the Latino stakeholder group Charrette, the selection of an issue area was used to write and submit a grant proposal. In the FQHC Charrette, the values, goals, and autonomy developed during the Charrette were applied toward producing several deliverables: a research question, a formalized research partnership between the university and the FQHC, and written governance documents for the CAB’s continued involvement in research.

Roles of Charrette Participants

The roles of various Charrette participants are not explicitly included as one of Kennedy’s eight characteristics. However, it is important to acknowledge the importance of ensuring transparency and clarity of the various participant roles involved in the Charrette. These roles can influence interpersonal interactions during the Charrette process, so attending to the power balance and promoting stakeholder voice and authentic representation is critical to the success of the Charrette process. This can be facilitated by using an experienced Charrette facilitator who is skilled at engaging all participants and minimizing power differences among various stakeholders including researchers.

Discussion

The experiences described above highlight how a Charrette can be successfully adapted to accommodate the needs of the stakeholders engaged in CBPR projects in community-academic partnerships. Having described the experience and characteristics of both Charrette processes, we close with a discussion of the successes, challenges, and practical issues that emerged over the span of each project and include recommendations for community and academic groups who engage patients and community stakeholders in the research process.

A traditional Charrette usually consists of short, intense sessions with community stakeholders to achieve a particular goal. The traditional format may not lend itself to long-term goals. Our case examples, while different from the traditional Charrette, adapted the process to meet the needs and timelines of the community stakeholders and project goals. In the case of the Latino stakeholder group project, the one-day Charrette workshop resulted in the identification of a core team of academic and community partners. This team ultimately formed a grant-writing team, which submitted the R13 grant proposal without the need for further Charrette facilitation. Though not funded, the proposal received constructive feedback from the NIH program officer. The team continued discussions about revising and resubmitting the proposal until two core members were unable to continue participation in the project. Although the team did not continue to pursue the resubmission of the R13 proposal, the community-academic partnership was made possible by the groundwork laid during the Charrette.

By contrast, the FQHC Charrette built capacity to develop a community-academic research partnership and goals over a 12-month period. The project timeline required that the Charrette activities be spread over a period of several months allowing the Core Project Team and CAB extended time to work with professional Charrette facilitators. Having several weeks in between the Charrette activities also allowed the participants to work independently toward the deliverables (without Charrette facilitators) and apply what they learned during the Charrette sessions. With this format, the group capacity and the research deliverables progressed in parallel. While the group capacity took longer to develop because it was less intense, the process was more truly participatory, and the team was able to develop the CER question independent of further Charrette facilitation. Despite differences in Charrette timelines, both cases showed evidence that the Charrette helped the groups develop autonomy and agency to pursue key deliverables without the direct help of the Charrette facilitators.

In addition to differences in timeline, the Charrettes had different starting points with respect to predetermined goals, logistical parameters, and objectives. With the Latino stakeholder group workshop, “pre-Charrette” planning was guided by the prescribed goal of a single key deliverable (i.e. selection of a priority focus area from a list of 14 contained in the R13 funding opportunity announcement) and an established three-hour timeline for the Charrette. Because of the pre-defined purpose, the feedback was focused on a specific topic (i.e. a health disparity issue) rather than exploring a broad range of potential projects. By contrast, the FQHC project included several key deliverables (see Case Example 2), but did not include a pre-identified issue for the CAB to explore.

For the FQHC project, the focus area was relatively open-ended. The CAB members needed to work diligently to produce several key deliverables required by the grantor. As such, the Charrette sessions were essential for establishing mutual expectations, trust, and participant-guided direction. The lack of a predetermined issue also meant that the group needed to establish its values and mission quickly in order to prioritize issues for further research. The Charrette activities focused on building capacity and trust among members, which quickly removed barriers and promoted fruitful discussions. The Charrette activities also established foundational values for the group, which provided structure to the decision-making process and informed the subsequent work. This allowed the CAB and project team to explore a wide variety of options. This resulted in the development of a research question related to food insecurity that was not initially envisioned by the Core Project Team.

Although the Charrette process can be applied in a wide variety of conditions, its success is subject to environmental and logistical factors. Researchers and project leaders should be aware of how the venue selected can affect group power differentials, cost, accessibility, communication dynamics, and technology capabilities. In both cases, environmental factors, especially location, influenced group communication and discussion during the Charrette process.

The one-day workshop with the Latino stakeholder group occurred in a large room setting that accommodated small and large group work, food tables (buffet style), and IT/AV equipment for presentations. The space was in a building used for older adult education, not in a high-trafficked area, and thus, there were no interruptions by other activities.

The initial PCORI Charrette sessions were conducted in restaurants arranged by the Core Project Team and located within the focus community. While these venues contributed to the sense of camaraderie among CAB members, provided neutral and accessible locations to convene, and were logistically easy to cater, they created challenges for the Charrette facilitators. Specifically, the lack of technology limited the explanation of activities, and the public setting was noisy and not conducive to small-group breakouts or sensitive discussions. After two meetings, researchers changed the venue to a conference room located in the FQHC clinic. While the conference room was not a neutral setting for all parties, there was noticeable improvement in group focus and communication in the private, quieter setting. While the restaurant settings highlight the Charrette facilitator’s flexibility, even in non-ideal situations, it also illustrates how environmental choices impact tradeoffs between accessibility, neutrality, and functionality.

Stakeholders can incorporate a Charrette into their broader CBPR project to either directly or indirectly achieve the project’s goals. Groups that focus their Charrette explicitly on the project’s deliverables, such as the Latino stakeholder group Charrette, may enjoy an enhanced rate of short-term progress due to the willingness of participants to contribute for a brief, intensive period of time. On the other hand, in groups where the Charrette focuses indirectly on project deliverables, participants may not experience the same intensive productivity, but may enjoy sustained relationships and increased capacity to work toward goals outside of the Charrette.

With the Latino stakeholder group project, it was important to capitalize on the group’s work during the workshop. Therefore, the Charrette was dedicated to timely engagement on tasks that needed to be done before the proposal could be written (e.g. survey to prioritize focus area for the R13 proposal). Within the three-hour session, the participants achieved several short-term goals, including forging consensus to submit for funding (direct contribution), narrowing the focus areas from the top three identified at the workshop to the priority issue identified by survey post-workshop (direct and indirect contributions), and identifying a core grant writing team (indirect contribution). Following the Charrette, the core team continued its work to successfully develop and submit the proposal. Even though continued work between the project partners halted once funding was denied, short-term goals of both university and Latino stakeholder group partners were achieved.

By contrast, the FQHC Charrette sessions were not directly focused on achieving the project deliverables, but were nevertheless invaluable for building group capacity and autonomy, contributing indirectly to the group’s objectives. As previously mentioned, the Charrette sessions were followed by dedicated discussion of the group’s deliverables, so the takeaways from the Charrette activity could be immediately applied in the context of the CAB’s work. The capacity built during the Charrette sessions also enhanced the group functionality outside of the monthly meetings, ultimately allowing the CAB and research team to make progress toward their goals without direct assistance from the Charrette facilitators.

Conclusion

Utilizing the Charrette process contributed greatly to successful partnership development for CBPR. The Charrette process in the Latino stakeholder group project was instrumental in achieving several successes, which ultimately yielded a submitted NIH R13 proposal. The Charrette to establish a CAB was a success on several fronts. Although the extended Charrette timeline created some challenges for patient and staff participation, the facilitated Charrette activities were invaluable in developing partnership between the academic and clinical practice partners and the CAB. Understanding the true meaning of patient-centered engagement work and being open to a patient and stakeholder organically-derived agenda was a rich, educational journey.

Overall, the projects enjoyed the most successful levels of collaboration when all partners were able to “Be Present” in conversations about research. This includes approaching research with a sensitivity to community partners who provide services to vulnerable populations and with the patients themselves. It was helpful to learn about the cultural history and its influence on perceptions of research within the community. Being open and attentive to concerns when they were voiced allowed clearly communicated intentions and created opportunities for co-learning. Using university resources to provide human subjects research training was an effective strategy to provide objective information and to facilitate open dialogue about historical perceptions.

While a traditional Charrette is characterized as short and intensive with immediate feedback on specific goals, the Charrette can be adapted and still be successful. Such adaptability lends itself particularly well to CBPR projects, which are dynamic by nature and emphasize stakeholder engagement. The Charrette can be a valuable tool for achieving this robust engagement. Kennedy et al.'s review of Charrette projects outlines key components of the Charrette for potential CBPR researchers. For researchers new to CBPR, the Charrette is an excellent tool for developing effective skills for engaging with, and ensuring shared participation from, all stakeholder participants. Using Kennedy et al.'s evaluation framework, our two cases illustrate a variety of ways CBPR practitioners may tailor the Charrette process to fit the needs of the project stakeholders.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the UNC-Chapel Hill Charrette facilitator team, Dr. Alexandra Lightfoot and Mr. Melvin Jackson for technical assistance and facilitation during both Charrette projects.

Case Example 1 project was funded by UNCW’s Office of ETEAL. Case Example 2 project was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Pipeline-to-Proposal Award 771-4584, administered on behalf of PCORI by the University of North Carolina, Wilmington

Disclaimer

The views, statements, and opinions presented in this work are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Corresponding Author

Correspondence concerning this article should be address to Dr. Stephanie Smith, UNCW School of Nursing, 601 South College Road, Wilmington, NC 28403. Email: smithsd@uncw.edu