INTRODUCTION

New York City and the COVID-19 Pandemic

New York City (NYC) was the first epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, and preliminary data in mid-April 2020 demonstrated that COVID-19 had already exacerbated well known health disparities (Rosenberg et al., 2020). While white people represented 18% of the COVID-19 fatalities across NY state, Latino/a/x/e (Latine) and Black people made up 30% and 37%, respectively (Rosenberg et al., 2020; Wallace & Wallace, 2021). Individuals from these marginalized populations make up a large portion of NYC’s essential workers but have historically been overlooked by authoritative bodies including policymakers, researchers, and medical professionals (Kantamneni, 2020; University of Illinois Chicago, 2021). Due to differences in socioeconomic status and other factors, these populations had less protection during the pandemic, putting them at higher risk of illness and death (Kantamneni, 2020; University of Illinois Chicago, 2021; Wallace & Wallace, 2021). However, NYC is home to numerous community-based organizations and networks that are committed to conducting research to help local communities get the resources they need (Madden et al., 2023), a critical effort to advance health equity.

Community Based Participatory Research

Community-engaged research (CEnR) has the potential to help public health professionals and social service organizations better support community members’ emergent needs during a crisis such as the pandemic; its emphasis on collaborating with community members to develop, implement, and/or analyze research may yield important insights on local populations’ assets, liabilities, and challenges (Goodman et al., 2017; Wallerstein, 2020; see also Nonpartisan and objective research organization [NORC] at the University of Chicago, n.d.). CenR, when conducted appropriately, utilizes a bidirectional approach. On one side, academic researchers seek guidance and direction from community members based on their unique lived experience. On the other, academic and community researchers share decision-making responsibilities or community researchers take the lead, resulting in a process more intentionally designed to disrupt power differentials traditionally inherent in research (Goodman et al., 2017; Wallerstein, 2020; see also NORC at the University of Chicago, n.d.).

Robust participatory CEnR approaches exist across disciplines, but there is one that is most recognized in public health efforts: community-based participatory research (CBPR) (Wallerstein, 2020). While CBPR shares many commonalities with other frameworks used in both health research and other disciplines, CBPR, and its principles, values, and practices have been deliberately and iteratively defined since the 1990s with the specific context of advancing health outcomes as the key focus (Wallerstein, 2020). CBPR, grounded in power sharing between academic researchers and diverse community partners during each step of the research process to explore questions of interest to the community, involves a more active community role than other approaches on the CEnR continuum (Wallerstein, 2020). The goal of CBPR, rooted in principles of social justice, is for research to result in action that advances health equity (Wallerstein, 2020).

Virtual Engagement

The pandemic, with restrictions around gathering in-person, limited the ability to conduct CBPR using traditional means, but CBPR practitioners who recognized both the value of CBPR and the importance of face-to-face time for relationship building and meaningful collaboration found themselves needing to adapt (Berhane et al., 2024). One challenge became how to effectively engage diverse collaborators on CBPR research processes such as developing interventions and co-identifying outcomes of interest. Another became how to virtually equip more researchers and community partners with the knowledge and skills to conduct CBPR, with their own adaptations.

Projects Aims

In this manuscript, we describe a virtual CBPR project conducted in NYC during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic aimed to: 1) Develop and pilot an infrastructure for virtual research idea generation 2) Pilot processes for virtually building the capacity of researchers and community stakeholders to conduct CBPR, and 3) Develop a virtual resource hub and concierge service for teams interested in further developing and implementing CBPR projects.

METHODS

Community Partnership and the PCORI Taskforce

With funding from a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Engagement Award, our team at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai identified 15 partners from a larger network of collaborators with a strong track record in community-engaged research to join a taskforce to support virtual CBPR. They represented diverse neighborhoods and populations across the five NYC boroughs, including populations facing disparate health outcomes, and were invited because of their deep connections to their communities. These collaborators included LGBTQ-serving providers, food pantry networks, settlement houses, federally qualified health centers, elected officials, youth-serving organizations, and wrap-around service providers.

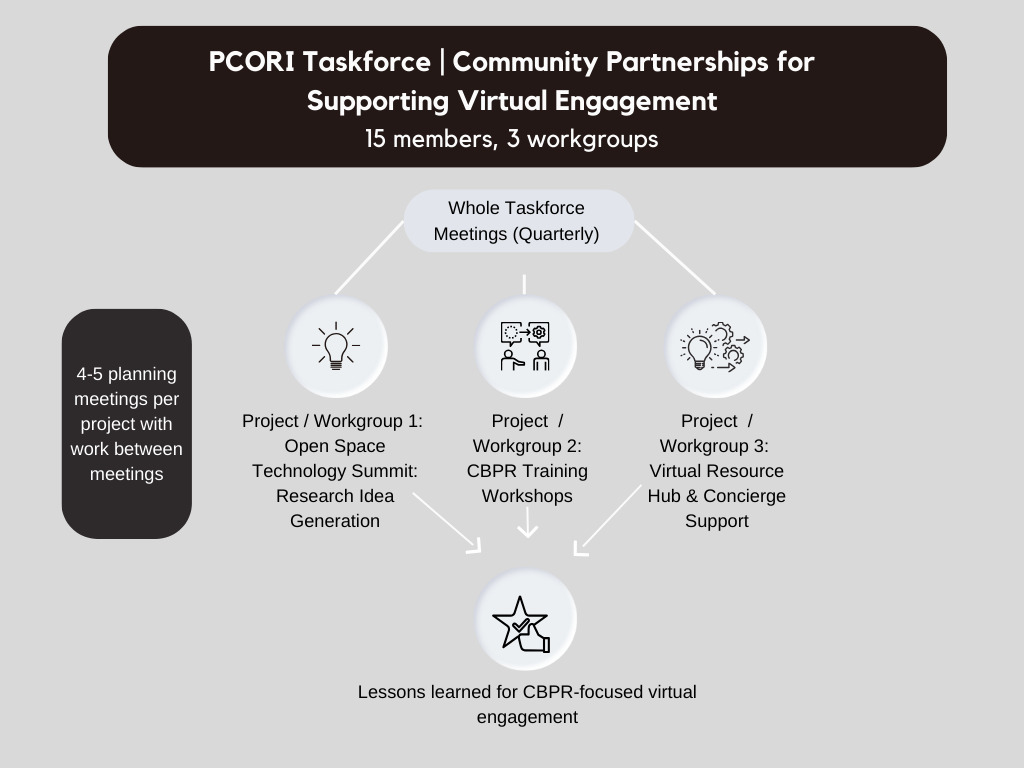

All invited partners came together to design and implement three core projects (see Figure 1). At a kick-off meeting, community partners introduced themselves, heard background about the project goals, and discussed plans to assemble three workgroups, each charged with one of the project aims. We then emailed taskforce members and asked them to rank their top two workgroup preferences to ensure equitable distribution across the workgroups (five in each group). Each workgroup determined their meeting frequency and met to identify and implement their goals; the whole taskforce reconvened quarterly to share updates across the larger group and solicit additional input, as needed.

We developed a survey to evaluate the taskforce partnership at the end of the project by adapting a previously developed survey examining the effectiveness of community-academic partnerships to advance public health (VanDevanter et al., 2011). We assessed, through Likert scale questions, members’ general satisfaction with the partnership and their role, organization and structure of meetings, trust, respect, effectiveness of communication between partners, decision-making processes, and perceived impact. We asked participants to reflect on two open-ended questions, including one question about their motivation for getting involved in the initiative and another on how they perceived the work could impact communities.

Open Space Research Summit

Workgroup members, committed to the idea that we needed more community-engaged research on COVID-19 that was relevant to the communities in greatest need, assembled to plan a virtual forum that brought community and academic partners together to crowdsource and prioritize COVID-19 related research ideas. The group, looking for a highly interactive method of engagement that would yield meaningful ideas, decided to leverage an Open Space Technologies (OST) format. OST is a time-bound but organic meeting methodology commonly used in sectors such as education and business to tackle complicated challenges that do not seem to have one clear answer but for which answers are of critical importance (Art of Hosting, n.d.). In OST meetings, there is no agenda established in advance, but instead facilitators strive to create an equitable space for idea-sharing and community building (Art of Hosting, n.d.). Generally, OST meetings take place in person, though, the format has been delivered virtually with people documenting their lessons learned for others to consider when employing this method (Berhane et al., 2024; Maljkovic, 2020; Sbradd, 2022). This includes strategies for participants to share topics they would like to see discussed and space for people to gather to openly discuss the topics proposed (Berhane et al., 2024; Maljkovic, 2020).

The “You, Me & COVID-19 Brainstorming Summit” used OST to co-build an agenda with invited community stakeholders and brainstorm broad topics for research that they wanted to collaboratively explore during the 2-hour Zoom-based session. Participants were invited by taskforce members through their organizations’ newsletters, social media, and other communication with constituents, or through their personal social networks.

To orient the participants to the meeting, and the OST format, a community task force member and a member of the research team introduced OST basics and the plan for the meeting structure before encouraging the creation of community-driven topics for breakout rooms in real time. Once the topic-specific breakout rooms were created, participants could join a room of their choice, and were invited to move from room-to-room if they wanted to join different conversations during the session, following OST protocols (Bright Green Learning, 2020; Maljkovic, 2020).

In OST tradition (Bright Green Learning, 2020; Maljkovic, 2020), there were no set questions to guide the conversations and no formal facilitators for the breakout rooms; participants were instead encouraged to see where the conversations took them organically, keeping in mind the goal of identifying research priorities going forward. Taskforce members took notes in the rooms using Jamboard, a centralized platform to share ideas, to provide access to discussion content to participants across the event in real-time and allow them to contribute to the notes, as they felt appropriate (Virto & López, 2020). Participants could monitor the notes and opt to leave one room and join another based on interest. Groups had up to 45 minutes for their discussions, but were reminded, following the principles of OST, that some conversations may end earlier, and some may need to continue at another time (Art of Hosting, n.d.).

At the end of the event, participants came back together as a large group and shared key takeaways from their discussions as well as personal reflections on their experience with the OST format. Following the event, Padlet links for each topic were sent to the participants with notes from the discussions and prompts to continue the dialogue. Padlet is a platform that allows an unlimited number of users to share ideas and files with one another to advance ideas and goals in an interactive but secure way (Padlet, n.d.).

At the conclusion of the event, participants were also invited to complete a 2-part feedback survey (see Appendix A). Part one consisted of nine Likert-scale questions on participants’ general assessments of the OST format and future intentions for engaging in CBPR. Part two consisted of four open-ended questions asking participants to share their thoughts on successes of the event and areas for improvement.

CBPR Training Workshops

Another Taskforce workgroup adapted a previously delivered in-person training on CBPR knowledge and skills (Goytia et al., 2013) into a new virtual format with the goal of making the training more widely accessible and ensuring more people, interested in supporting health equity, could begin using CBPR approaches. During three initial monthly meetings, community partners came to consensus on the intended audience for the workshops (individuals from both CBOs and academic institutions interested in learning about CBPR), identified topics to be covered during each session (ranging from how to build and sustain community partnerships to how to secure funding), and confirmed logistics (i.e. dates, time, length and frequency of the sessions). In subsequent weekly meetings, a smaller team converted previous training content into a virtual delivery format, reviewed potential supplemental resources, and identified virtual tools (e.g., Google Jamboard, Youtube videos, and PollEverywhere) to increase participant engagement and minimize “Zoom fatigue”, the COVID-era discovered phenomenon of exhaustion that participants experience from so much computer facetime (Berhane et al., 2024; Ramachandran, 2022; see also: Bailenson, 2021).

Sessions included interactive content related to CBPR background and methodology, the implementation of CBPR principles in program planning and evaluation, and how to translate CBPR into action (i.e., programs and social and/or policy changes). The workgroup reviewed and provided feedback on the PowerPoint slides for each session as well as supplemental materials for review after each session before presenting them to the participants. Table 1 displays the content covered in synchronous and asynchronous sessions.

We advertised the workshops using promotional flyers and limited enrollment to the first 15 participants to register to keep an intimate, interactive learning environment. Due to high demand, with target registration numbers reached within hours of disseminating promotional materials, we created a waiting list for future workshops. Ultimately, three cohorts of twelve participants participated in the training (cohorts 1 and 2 from February through April 2021 and cohort 3 from April through June 2021). Two co-facilitators led a 2-hour virtual workshop per month, with suggested digital content shared after each monthly session (a total of three “online” and three “offline” sessions). Community and academic experts with robust CBPR experience facilitated parts of the sessions as guest speakers, highlighting their experiences with topics such as community and trust-building, large-scale needs assessments, and the importance of community engagement in program evaluation research.

Participants were encouraged to complete individual session feedback surveys and an exit survey upon conclusion of the program. Session feedback surveys included seven Likert-scale questions on participants’ assessments of the sessions and the use of virtual tools to increase interactivity and engagement, as well as two open-ended questions about successes and areas for improvement. The exit survey consisted of eleven Likert-scale questions on participants’ overall assessments and experiences during the workshop and five open-ended questions regarding workshop successes, recommendations for future topics, interest in networking opportunities, and areas for improvement (Appendix B). The core training team also conducted informal debrief sessions after each session, which led to as needed revisions that were integrated for the next cohort.

Virtual Resource Hub

A third Taskforce workgroup identified relevant CBPR topics to build an online repository of resources for researchers and community members with different levels of experience with CBPR. Through zoom meetings and follow-up emails, workgroup members created a list of different topics they felt were important to cover and prioritized 6 main domains to include: 1) CBPR: Basics and In Action, 2) Grants and Budgets, 3) Research Methods, 4) Program Planning and Evaluation, 5) Disseminating Findings, and 6) Citation Resources.

Subsequently, workgroup members started compiling potential resources (e.g., PDFs, articles, toolkits, videos, blog posts, and more) to include in the repository under each domain. We then developed a spreadsheet to help sort through and vet the resources identified. The vetting tool included guidelines to assess each resource’s literacy level, intended audiences, the time commitment required to review the resource, and other relevant information. We established a consensus system in which at least two people were assigned to review each resource, populate the vetting tool, and vote on whether the resource should be included. Finally, we created a summary of each resource to help guide and orient users of the repository.

Working with a web developer with background in user experience, we developed a website infrastructure that would allow visitors to review and click on overarching headings at the top of the home page, or subheadings further down. Within each broad topic, users are able to filter resources by type (i.e., if users are interested in video content, they can browse videos). Additionally, people can suggest additional resources for us to consider and share the kinds of resources or information they are seeking that may not yet be covered by the site.

Prior to launching the website, we presented it to the workgroup for feedback and final approval. The website went live in August 2021 and taskforce members started to promote it within their organization and networks. We also shared with our broader Research to Action Network, Mount Sinai’s Institute for Health Equity Research social media platforms and website, and participants who had attended either the virtual CBPR training or a project dissemination webinar hosted in September 2021.

RESULTS

Taskforce Collaboration

Of the 15 original taskforce members, two had to step down due to other responsibilities. Our evaluation of the taskforce included survey responses from 11 of the 13 taskforce members who remained engaged for the duration of the project (85% response rate). The majority of participants (10 of 11) expressed that they felt a sense of ownership in the projects and partnership with one participant noting a neutral response. Nine (9) of the participants reported that they could talk openly and honestly at workgroup meetings, that taskforce members showed respect for one another’s points of view, and that there was trust among the group. Communication was deemed focused and productive (9 of 11) and efficient (8 of 11), with additional respondents selecting ‘neutral’ as their answer choice.

When considering impact, 7 members of the taskforce agreed/strongly agreed that both academic and community partners could clearly communicate to the community the relevance of their actions, with no one disagreeing. Additionally, 8 respondents agreed/strongly agreed that the partnership had a positive effect on the community, and 9 noted that their organizations directly used knowledge the project generated. Again, no participant disagreed with these statements. When asked why they chose to get involved in this initiative, taskforce members mostly discussed the potential for community impact. One taskforce member spoke specifically to the importance of this work in the context of COVID-19, writing, “Exploring and understanding new modalities of engaging in CBPR and academic-community partnerships are essential to transforming how we adapt to our new post-pandemic reality.”

Open Space Research Summit

Of the 120 registrants, 75 participants attended the OST summit which included both community and academic research partners. Participants generated 17 different COVID-19 relevant research topics including but not limited to mental health burden on children and adults, financial impacts, equity in healthcare systems, and interpersonal relationships. Topic selection during this online, time-limited OST event was done quickly while everyone was in the main Zoom room, and we do not have a record of how many participants voted for each topic in the moment. However, the 10 most popular topics selected to explore further in breakout rooms included: 1) isolation, 2) vaccine hesitancy, 3) immigrant experiences, 4) mutual aid, 5) food access, 6) impact on children (development and mental health), 7) memorializing the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement, 8) single parent households, 9) people living with disabilities, and 10) housing (including eviction support and neighborly conflict). The breakout rooms that created the most robust Jamboard records included vaccine hesitancy, immigrant experiences memorializing the pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement, and housing. The breakout rooms with the least traction included isolation, single parent households, and people living with disabilities, though there were always people in each breakout room.

Of the 75 participants, 15 responded to the post-survey for a response rate of 20%. Overall, 14 of the 15 respondents agreed/strongly agreed that they liked the OST format of the event, and all 15 agreed/strongly agreed that their ideas and opinions were heard, valued and respected (Table 2). Additionally, 11 of the 15 respondents indicated that they planned to put their ideas from that day into action. There were a few outlier responses, with one participant disagreeing that the information provided during the session was clear and easy to understand, one participant disagreeing that they liked the format of the event, and one participant disagreeing that they would recommend this event to a friend.

Many of the participants reflected on the organization of the event, and several spoke to the quality of the discussions they had. One participant wrote, “I really enjoyed the format of this event. In the breakout room I was [in], we kept the conversations for the whole event. Very interesting conversation and people.” Another noted, “[…] I had initially wanted to split my time between a few groups and ended up being so engrossed by the first one that I ended up staying there the whole time.”

When asked about what could be improved for future events, a few participants expressed the need for more clarity around next steps, asking for more information about how the outputs would be leveraged. For example, one participant wrote, “[…] What will happen to all of the ideas shared during the session? Who owns this “intellectual capital” […]?” However, most feedback focused on ways to make processes more efficient and sustainable, with participants sharing ideas for timing around activities. For example, one participant shared that they wanted more time at the end of the event for groups to report back and implied that structured time for the members of different breakout sessions to connect with each other might prove useful in helping them build out the work moving forward. CBPR Training Workshops

Of the 36 participants who attended the CBPR training workshops, 20 responded to the exit survey for a response rate of 66.7%.

Overall, 95% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they learned something from the training and felt confident that they could immediately apply what they learned in their own program or project. Furthermore, 85% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the information shared by the CBPR experts was particularly helpful and requested more time to discuss real-world CBPR applications with them in future sessions.

Regarding virtual tools, 60-70% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that tools like Google Jamboard, YouTube videos, and Poll Everywhere enhanced their learning experience, and 80% of respondents felt positive about using breakout rooms for group activities.

In open-ended responses to the question “What did you like about the workshops?”, several people noted the guest speakers, real life examples, case studies, interactive nature of the workshop, and ability for the facilitators to create a comfortable space for “learning, sharing, and participating” (participant quote). When asked, “What would you change or want to see improved?”, a couple of participants suggested additional sessions. Other common themes that emerged included 1) hosting more CBPR guest speakers and simulation activities; and 2) offering workshops in other languages to increase accessibility (including American Sign Language).

Virtual Resource Hub

We tracked user engagement of the online research repository using Google analytics. Preliminary analytics of the first year showed that from the launch of the website in August 2021 up to the end of August 2022, the webpage had been accessed at least 615 times by 542 unique individuals. The site views came from across the globe with the United States and China having the highest percentages at 68.3% and 18.9%, respectively. Other users were from Canada, Australia, India, United Kingdom, etc., and at least seven cities, with New York City (25%) and Shanghai (7%) having the highest engagement rates. The homepage of the website was the most visited page (56%) followed by the resources on Research Methods, Grants, CBPR, and Program Planning and Evaluation pages respectively.

Most of the traffic to the website was direct, as a result of our efforts to continuously promote the website, followed by organic searches, referral from other websites, and social media.

DISCUSSION

Through this project, with the COVID-19 pandemic taking its toll in the background, a taskforce of community and academic partners convened, virtually, with a commitment to advancing community-based participatory research approaches for fostering health equity. Together, they piloted virtual processes for bringing diverse stakeholders together to identify priority areas for research, conduct cohort-based online courses in CBPR skills building, and launch a web-based CBPR repository. The process of coming together remotely to develop and implement these projects became a case study for best practices in virtual engagement to advance CBPR.

Maintaining Principles of Engagement and Participation When Going Virtual

Though we had concerns about how fruitful virtual collaborations would be given the fatigue and many stressors associated with both living through the pandemic and having to reimagine day-to-day lives in a way that centered socializing, communicating, and getting work done in online spaces, we aimed to maintain a commitment to principles of CBPR (Collins et al., 2018; Israel et al., 2013) as we built this collaborative taskforce and implemented the three projects.

Principles of Engagement: Activating a Taskforce

The taskforce, and the work that transpired among the group, was foundational to each of the projects they implemented. Therefore, it is important to consider the larger scope of this work through the lens of whether the taskforce itself was rooted in core tenets of CBPR. Israel’s (2013) third outlined principle of CBPR, and one that emphasizes CBPR’s position on the more participatory side of the CeNR spectrum (Wallerstein, 2020), notes that "CBPR facilitates a collaborative, equitable partnership in all phases of research, involving an empowering and power-sharing process that attends to social inequalities." Collins et al. (2018) articulates that this includes, but is not limited to, community partners being active co-creators of interventions, coming to the table with their community’s best interests in mind. Despite the need to develop and implement projects virtually, taskforce members’ evaluation responses indicate that they felt the process of building and implementing the three projects was inclusive, equitable, and meaningful; they were co-owners of the projects, bringing their unique lens into the process. Given that building trust in CBPR takes time, we deliberately engaged partners we had previously worked with. This may have contributed to participants’ sense of ownership and ease of communication and should not be understated.

Additionally, it is important to note that although we conducted this project virtually, we still employed proven effective practices for taskforce engagement. Member influence is often articulated at the first taskforce meeting which, in many ways, can set the tone for how the taskforce will function and whether members will see their participation as valuable (Wilkinson, 2021). In line with these principles, at our online kick-off meeting, we went over the charge from the funder and provided some general infrastructure guidance but created time for discussion and explained that each of the workgroups would be responsible for developing their own processes and methods for executing the work. Throughout the project, we also made sure to assess where we needed to pivot, another critical means to achieving taskforce success (University of Kansas, n.d.). For example, we debriefed after every CBPR workshop to discuss what went well and where we could improve, adjusting future lessons as necessary. This ensured that there was structure, but allowed flexibility and creativity, and likely contributed to the favorable experience that taskforce members reported. Finally, successful taskforces are often small (University of Kansas, n.d.); our sizing considerations enabled taskforce members to equitably distribute the work across groups in a way that felt manageable and coordinated (Keefer, 2017).

Principles of Engagement: Soliciting Community Perspectives for Research

While this project was not a research study, the taskforce was interested in applying CBPR approaches through virtual platforms to generate new research ideas. If guided by CBPR principles, research ideas are not generated by academic researchers but rather through collaborative processes that create space for community’s ideas and concerns, particularly those rooted in inequities (Maljkovic, 2020). The OST summit gave the taskforce an opportunity to pilot processes for collaboratively identifying research areas of concern.

Though perhaps not a traditional mode of doing this, results from the OST pilot indicate that community stakeholders found this method to be engaging, fulfilling, and productive, suggesting that it might have value for others in public health who are looking to authentically engage with their constituents to prioritize research agendas or learn about key concerns with efficiency and urgency, even when they cannot be together in a room, face-to-face. While OST is traditionally offered in-person, there are several guides available to support those interested in hosting such discussions virtually (Bright Green Learning, 2020; Maljkovic, 2020; Sbradd, 2022). The foundational principles, grounded in flexibility and recognizing participants as experts (Hopkins, 2008), that make OST a success with participants in-person remain the same online (Maljkovic, 2020) our participant responses indicate these principles lent to a positive and constructive experience.

Principles of Engagement: Remote Learning on CBPR

Similarly, it is important to consider the positive CBPR evaluations against the stance that pedagogy will be successful regardless of whether teaching happens in-person, remotely, or through a hybrid method so long as educators follow pedagogical best practices (Harvard, n.d.). This includes considering, no matter if online or off, how the material is delivered; students of diverse learning styles should always be given the opportunity to interact with what they are being taught (Harvard, n.d.). The Detroit Urban Research Center (URC) offers a CBPR Partnership Academy that is a leader in setting participants up for success in this field; they suggest that training opportunities work best when all participants have opportunities to learn from other participants in the course, the learners have an opportunity to practice putting what they have learned to use, and participants help direct what they want to learn about (Coombe et al., 2020). This is what we strove for in our virtual course. Our participants’ optimistic responses to the curriculum we implemented may be, in part, attributed to our application of these principles; each session provided an opportunity for open class discussion, small group skills-practice, and feedback on additional content to introduce in follow-up sessions. Participants cited the effectiveness of breakout rooms for small-group communication and reflection, learning from guest speakers’ firsthand experiences, and online tools to help them engage with the material, emphasizing the importance of thoughtful content delivery.

Principles of Engagement: Building Useful Online Resources and Tools

With the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, supporting more CBPR projects on topics that mattered to local communities and equipping researchers, public health professionals, community advocates, and community members with the resources they needed became a clear priority. In the last couple of decades, due to the rapid development in technology, digital repositories have increased in popularity and have become hubs for students, scientists and other diverse stakeholders to access research and learning materials, gradually replacing brick and mortar libraries (Collura et al., 2019; Witt, 2018). However, we did not want to build something that would not be useful. Again adhering to principles of CBPR, we developed our digital research concierge service with community partners who identified the main domains that would respond to their needs, helped us vet the related material/resources, and disseminated the repository to a wider network of CBOs.

In the development of the repository, the coalition incorporated best practices for accessibility in webspace design (EBSCO Information Services, Inc., 2015; see also: 99designs, 2021; Lawrence & Tavakol, 2007; Vrana, 2010). All content was grouped under 6 main domains, with short, straightforward headers indicating the type of content the user would find in each tab. All the collected resources were tagged with one or more corresponding formats, so users would have the ability to sort and filter by resource type (video article, video, toolkit, etc.,), and applicable resources were also linked to external content. Additionally, the digital repository displays a “contact us” feature where users can share recommendations for additional content, pose questions about the website or specific projects, and request consultation services (Hee Kim & Ho Kim, 2008). We choose website colors and overall design based on recognized aesthetic and usability considerations (EBSCO Information Services, Inc., 2015; see also: 99designs, 2021; Lawrence & Tavakol, 2007). We also adhered to the main principles of usability emphasized by web developers to design a user-centric website that is easy and efficient to use: 1. Availability (ease of access); 2. Clarity; 3. Recognition (the learning process required for users to navigate the website); 4. Credibility; and 5. Relevance (99designs, 2021). Implementation of these best practices into our design led to diverse user engagement, which increased gradually over time.

Challenges and Limitations

Across the three projects, there were challenges and limitations that are worth noting; some may have been a result of the limitations of technology while others may have surfaced regardless of implementation digitally or in-person. One cross-cutting limitation is that we did not collect granular information about participants’ roles on feedback form, so we could not distinguish when feedback was coming from a community researcher or academic partner.

Virtually Soliciting Community Perspectives for Research

OST strives to create space where participants’ most urgent ideas are amplified (Art of Hosting, n.d.). However, in our abbreviated experience, we did not have enough time for all of the ideas that were presented to be discussed at length. This was partially a result of our team’s capacity on the technology support side and the size of the event. We wanted to ensure that all breakout rooms had enough people in them to stimulate robust discussions, so we limited the number of rooms and had to distill the topics from the overall list to ten priority topics in real time. For this event, we relied on an intuitive process, identifying topic areas that were suggested multiple times in similar terms and merging ideas with commonality. Still, some breakout rooms had few participants, and some topics were more popular than others. While this is acceptable in OST given the emphasis on flexibility and participant choice (Art of Hosting, n.d.) future similar forums could employ participant polls and more advanced technology to prioritize the most relevant topics for further exploration.

The workgroup organizing this event grappled with how to support the participants in bringing the ideas they cultivated in this OST session to life. Although we developed an infrastructure for maintaining conversations that we hoped members would utilize, there was less engagement in these follow up discussions than anticipated. In future work, we will explore workgroup members’ suggestions shared during debrief meetings at the end of the project to maintain momentum for projects inspired by future similar events.

Additionally, the concerns that participants cited around intellectual property speak to current and historic abuses of power exercised by researchers, public health professionals, and the academic medical field (Newman, 2022). When participants pointed out their concerns, we realized that we had not explicitly acknowledged our role in systems that still often uphold such power dynamics and, as a result, may not have created an environment in which all participants felt safe to authentically share their ideas. Recognizing the responsibility we have to create and nurture those spaces (Newman, 2022), we communicated our missteps to participants and clearly articulated that we would not be advancing any of the research ideas generated without mutually agreeable collaborations with those who inspired the ideas. We have remained true to this word and have offered our support to ideas that have moved forward.

Virtual CBPR Capacity Building

Based on attendee feedback and our analysis we found several areas for consideration for future workshops, as noted in the results. Given the response to the workshops, including the number of people who expressed interest, there is a clear need for this work. However, we were only able to scratch the surface of the participants’ needs, and their responses indicate that they felt more time would be helpful to dig deeper into the topics presented. Pathways for further learning should be more readily available to those who want to continue learning.

Some of the lessons the facilitators and coalition learned were directly related to the utilization of virtual tools for activities that encourage group interaction and enhance learning experiences across varied groups of stakeholders without relying on advanced technological competency (Berhane et al., 2024; see also Robinson, 2018). As many people will continue to do more of this work online in the coming years (Arif, 2021), consideration of virtual application of CBPR learning opportunities has immense value for those looking to advance health equity research, and our team has published additional resources to support these efforts (Berhane et al., 2024).

Building Useful Online Resources and Tools

It became clear that auditing content periodically is essential to ensure that users have the most up-to-date and relevant sources of information. With competing priorities of the workgroup members and funding cycles coming to an end, we have had limited capacity to regularly add new relevant resources or audit existing ones. Furthermore, although we promoted the website through social media and other websites, the engagement rates and visibility of the website did not progress as much as we had anticipated, and it is unclear to what extent we reached our intended audience with the limited analytics we were able to examine. In future work, we plan to continue to identify additional dissemination strategies to ensure that more CBOs benefit from the digital repository and broader research concierge service. Providing easily accessible platforms and resources to researchers remains a crucial priority to support future CBPR projects and community-initiated and centered health equity research.

Conclusion

The virtual CBPR-capacity building project conducted in New York City during the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the importance of adapting to virtual formats, and the readiness- and willingness of community stakeholders to do so to address health disparities and inequities. The workgroup of academic researchers and diverse community partners we convened was able to successfully create and pilot platforms for digital engagement that resonated with our communities and aligned with principles of engagement we have previously employed in person.

Moving forward, it is essential to sustain and expand the efforts made during this project. Continued collaboration between academic institutions, community-based organizations, and local communities will be crucial in addressing ongoing health challenges and fostering meaningful research with long-lasting impacts. The landscape has shifted, and it is now hard to imagine a future in which virtual engagement is no longer an option. Looking back on what worked well with virtual CBPR projects conducted during the pandemic can yield more productive, fruitful, and collaborative virtual engagement processes moving forward (Berhane et al., 2024; Madden et al., 2022).

As the world navigates through the aftermath of the pandemic, the lessons learned from this project should inspire further investment in the creation of inclusive platforms that empower communities to drive research agendas. By embracing the principles of community-based participatory research and finding ways to spread knowledge and awareness of these principles, including through digital strategies, we can build a more resilient and equitable public health landscape that leaves no one behind.

STATEMENTS AND DECLARATIONS

This study was funded by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) through the Engagement Award Program. Award number: EAIN-00185

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In addition to the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) as the funder of this work, we would like to acknowledge the following individuals and the organizations they represented for contributing their time as taskforce members.

TASKFORCE MEMBERS

Guedy Arniella, Institute for Family Health

Tenya Blackwell, Arthur Ashe Institute

Andrew Frazier, GMHC

Halimatou Konte, African Services Committee

Cinthia De La Rosa, Hester Street

Christopher Leto, Riseboro

Antonette Mentor, Montefiore Medical Center

Daniel Reyes, The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community Center

Bryson Rose, Hetrick Martin Institute

Judith Secon, New York Common Pantry

Benjamin Solotaire, City Council/North Brooklyn-District 33

Ingrid Sotelo, Union Settlement

Dorella Walters, Gods Love We Deliver