Introduction

What is co-creation research

Co-creation research involves stakeholders in the research process to create knowledge and tools that are both academically sound and practically useful. This type of research encompasses various traditions and concepts, including participatory and community-engaged research, participatory action research, and open innovation. Greenhalgh et al. (2016) reviewed the literature on co-creation research, finding it emerged in fields like business studies, design science, computer science, and community development. The definitions of co-creation, co-production, and related terms vary widely across research disciplines, leading to a lack of conceptual clarity. Following Smith et al. (2023), we choose not to waste time searching for the ‘True co-production’ but rather embrace the diversity of definitions. In this article, we define ‘co-creation research’ as involving all stakeholders to produce outcomes beneficial to both the research field and the communities involved. This definition requires an expanded epistemological understanding of what counts as knowledge and whose knowledge is valued. Common features of co-creation research projects are the recognition that researcher-truths are situated and partial and the emphasis on the importance of doing research with people and not about or for them, which requires participatory research methods (Phillips et al., 2022; Reason & Bradbury, 2008; Slattery et al., 2020; Van der Zouwen, 2022). While many articles on co-creation research advocate for including various stakeholders, they often lack strategies for creating change in the wider system (Beckett et al., 2018; Slattery et al., 2020).

Article structure

In this article, we present a model for levels of engagement to explain the importance of a strategy for change in enhancing impact. We then introduce the Large Scale Interventions (LSI) approach as a strategy for co-creating knowledge and change with the whole system of stakeholders. Following this, we illustrate the application of the LSI approach through a 3½-year research project titled “Impactful Graduation in Dutch Higher Education.”

We will detail the crucial role of a steering committee consisting of a cross-section of the system. Furthermore, we outline a method for co-designing the research process with this steering committee and describe how tools are developed and implemented. Tools are developed in co-creation with stakeholders for use on the micro-level (concrete graduation projects), meso-level (concrete education programmes) and macro-level (scenarios for organising graduation programmes with impact). We conclude the article with a reflection on the extent to which we successfully applied the LSI principles in the example project. We also share our lessons learned and provide recommendations for co-creating research with the whole system of stakeholders.

Levels of engagement

To have impact in the system, development of ownership and capacity for change in the system is required. (Burns, 2007; Van der Zouwen, 2011). Table 1 presents a model with five change strategies and their level of engagement of stakeholders, ranging from zero engagement (Tell) to maximum engagement (Co-create).

The Tell-Sell-Test-Consult-Co-create model was developed for organisational change by Brian Smith (in Senge et al., 1994). In Table 1, we adapted this model for the role of stakeholders in a research project, ranging from very passive to maximum co-creation. Bennebroek Gravenhorst et al. (2003) made a similar distinction in their research on change strategies, providing configurations to develop ownership and change capacity of organisations in relation to the level of engagement of stakeholders, which we added to Table 1. Unsurprisingly, the lower the engagement of stakeholders, the lower the development of ownership and change capacity in the system will be, and vice versa. Which change strategy is best depends on the aims of the process. For research projects, if the aim is to contribute to impact in the system, the higher the level of engagement, the higher the chances of ongoing change. So, ideally, stakeholders are involved at all stages of the research, in equal and reciprocal relationships, sharing responsibilities and ownership. In the next section we will introduce the Large Scale Interventions approach (LSI) as a strategy for co-creation research with impact in the system.

LSI as an approach for Co-creation Research

Principles of LSI, a type of Action Research

LSI is an approach to change and learning in which stakeholders of the whole system are invited to contribute at all stages. In an LSI trajectory, the whole system is invited on one or more occasions into one room, the so-called large group conference, to explore dynamics in the system and to address strategic issues. When also used to develop and share new knowledge, we see LSI as a type of Participatory Action Research (Burns, 2007; Reason & Bradbury, 2008; Van der Zouwen, 2011). We see systems not as fixed entities; they are ways of thinking that help us understand the different realities experienced by stakeholders. A system includes people and institutions connected to an issue, forming a dynamic ecosystem of those affecting and affected by the change (Weisbord & Janoff, 2010).

From her 7 years of field research on success factors and the effects of change with a whole system of stakeholders, Van der Zouwen (2011) has distilled four basic principles and the underlying assumptions that make LSI work:

-

Systems thinking: Events are connected in time and space. Change in one part of the system affects the whole system.

-

Stakeholder participation: Active stakeholder participation and self-management promote ownership for action and learning.

-

Action learning: Learning by doing together contributes to shared understanding; not separating thinking and doing in time or in the roles of the participants contributes to change in real time.

-

Sensemaking: Searching for new meanings with head, heart, hands and soul contributes to finding common ground for action to realise a desired and feasible future. Conflicts are rationalised, not resolved. The focus is on future possibilities, not past problems.

An LSI process is flexible and can take many forms, but a structure with an alternation of small and large group meetings is typical. Figure 1 provides an example of the main architecture of an LSI process for change with the whole system.

Working with a microcosm steering committee

In a research project, managing complexity and creating ownership for change means adapting research methods to make them accessible and meaningful to different stakeholders. It also requires flexibility in research design, working with emergent and multiple methods in a learning architecture with parallel activities (Burns, 2018). If anyone who is relevant must be able to participate, then we need methods that require little or no training and support, as much self-management as possible, and a variety of products (intermediate and final) for different target groups. As a consequence, many questions have to be answered during a co-creation research project. How to select and make inquiries with a range of stakeholders? What methods, language, locations, timing, and pacing are appropriate? Academic researchers cannot answer these questions alone; they need to collaborate with stakeholders from the outset to find out what works, in an ongoing and cyclic process. That is why an LSI process is co-designed and co-produced by a steering committee of relevant stakeholders. The steering committee is also called the leadership group, co-design team, planning team or similar names. For this article, we will call this group the 'steering committee’, although we think none of the terms mentioned adequately cover the variety of roles and responsibilities. The steering committee is more than an advisory board, focus group, sounding board or co-design team. It is a group of stakeholders who design, invite, lead and host the research process for the whole system. It does this best when it reflects the diversity of the whole system, as a cross-section of it. This cross-section is also called a ‘microcosm’ of the system of stakeholders (Lewis, 2021; Weisbord & Janoff, 2010).

What makes a steering committee successful? Van der Zouwen (2011) developed an evaluation instrument for LSI projects. A key success factor for a steering committee in LSI projects is collaborating on all decisions regarding the design, management and logistics for the working conferences as well as for the larger change process. Table 2 presents indicators that illustrate how this success factor can be effectively implemented in practice.

As a cross-section of the system, the steering committee reflects the system’s dynamics and vice versa. When the indicators for success are implemented, the steering committee also serves as a role model with which stakeholders can identify over an extended period. Consequently, the steering committee acts as a beacon of reliability for both the participants in the process and the grant provider (Kouzes & Posner, 2007; Van Vucht Tijssen et al., 2013).

In the next section, we will demonstrate how the LSI approach can be applied to co-creation research using the ‘Impactful Graduation’ project as an example. We will emphasise the crucial role of the steering committee.

Example project: Impactful Graduation in Higher Education

Problem and intended system change

Each year, over 30,000 students graduate from Dutch Higher Economic Professional Education (HEPE) courses at universities of applied sciences (UASs). While most of their graduation projects involve working with companies or businesses, these projects often fail to provide the desired practical value. Previous research (Munneke et al., 2018; Van der Zouwen et al., 2016) has identified several factors contributing to this issue. Currently, there is a strong emphasis on using academic research methods for writing bachelor theses. The educational requirements heavily influence how graduation project trajectories are organized in professional bachelor programs. This situation is deemed unsatisfactory by all stakeholders. Consequently, many bachelor programs in the field of economics are seeking ways to enhance the value of these projects for all involved parties.

To begin a process of research co-creation, problems need to be continuously and collaboratively identified (Becket et al., 2018; Dick et al., 2015). In our example project, hereafter referred to as ‘Impactful Graduation project’ or ‘example project’, this problem-identifying process was started in a preceding pilot study, initiated by the simple question of a teacher-researcher, ‘What do you gain from graduation projects?’ (Van der Zouwen et al., 2016). This pilot study was conducted with a research group consisting of teachers, students, and researchers and included two member check workshops with partners from the practice, students, teachers, and researchers, based on the LSI principles (Van der Zouwen, 2010).

In the Impactful Graduation project, students and their graduation trajectories are placed at the heart of the dynamic knowledge triangle formed by research, education and professional practice. The main purpose of this research was to generate sustainable change in HEPE by developing comprehensive scenarios for graduation trajectories with impact. We defined impact as having added value for all involved parties, not only for students but also for partners from practice, education and research institutions.

Research design

The Impactful Graduation project was initiated by three authors of this article, Lisette Munneke, Els van der Pool, and Tonnie van der Zouwen, who formed the core research team. As a consortium partner, we invited the Sectoral Advisory Board (SAC) for the professional field of economics, which is part of the Netherlands Association of Universities of Applied Sciences. We formulated the main line of the research design and applied for funding by submitting a research proposal to the Netherlands Initiative for Education Research (NRO). Our goal was to identify needs and to develop multiple scenarios for impactful graduation through close collaboration with the whole system, including educators, program leaders, students, research groups, and partners from the practice. The project was based on the LSI approach for co-creation, supplemented by a research track involving case studies and surveys to understand current patterns and values regarding graduation in professional education.

As soon as the funding from the NRO was granted, the three initiators formed a research group of nine researchers from the three participating universities of applied sciences (UASs). Sub-teams conducted parallel case studies and surveys. For this article, we will not elaborate on the content regarding higher education but zoom in on how the system of stakeholders has been engaged in co-creating the research project, beginning with forming a steering committee.

Co-creation with the steering committee

Soon after the start, the core team formed a steering committee to represent a cross-section of the system. We invited people with a good network in their stakeholder group who can help determine what is important to create impact in the knowledge triangle. Although there were some changes in the composition of the steering committee, most members participated throughout the whole project. The steering committee always consisted of about 12 people:

-

Two or three students/recent alumni.

-

One or two programme coordinators/teacher supervisors.

-

Two executives/administrators from organisations in higher education, also representatives of the Accreditation Organisation of the Netherlands and Flanders (NVAO).

-

Two or three experts from professional practice/company supervisors of graduate students.

-

The three members of the core research team.

The steering committee met a total of 12 times, with half of the meetings conducted online via MS Teams due to COVID-19 measures. We worked co-creatively, according to the principles of LSI, not only discussing issues but also collectively creating overviews of all findings and patterns on the wall. The hierarchy was minimized, similar to the large group meetings, by alternating between (anonymous) individual contributions to an overview or story, small group work sessions, and sharing insights and products in plenary sessions. Figure 2 shows an example of the steering committee being actively involved in the design of the research process. They are selecting the quality criteria that any tools should meet for further development.

By focusing on co-creating overviews and results, where everybody’s contribution was needed and valued, all members felt free to participate. A detailed report was created for each meeting in the form of field notes, including photos of the process and results. This provided a substitute experience for those who could not attend.

A long timeline as a tool for co-designing the research process

Throughout the project, we used a long timeline as a co-design tool for the research process. In the onsite meetings, we used a 4m-wide sheet of paper. During the online period, in the middle year of the project, this timeline was replicated on a digital wall in Miro, as shown in Figure 3. A readable version can be accessed on Miro; see https://miro.com/app/board/uXjVNV00Qis=/?share_link_id=792063662933. We used the timeline for scheduling or re-scheduling our meetings and conferences, as a growing overview of the research tracks, for planned and realised products, and to identify who is already engaged and who else should be invited. It also provided a visual summary of the entire research process. Detailed instructions on how to use this tool for co-designing with a microcosm steering committee are provided in the book ‘Co-creation in work meetings. Making the invisible visible’ (Van der Zouwen, 2024).

Table 2 summarizes how the steering committee contributed to the Impactful Graduation project. In the ‘Lessons learned and recommendations’ section, we will evaluate and discuss the steering committee’s role further.

Three co-creative conferences with large groups of stakeholders

To effectively develop and share diverse knowledge and tools, we organized three large group working conferences, each held approximately one year apart. Each conference lasted about five hours and involved a total of 174 unique participants from 22 universities of applied sciences (UASs) and 16 companies/institutions.

How people enter a meeting, their expectations and commitment are largely determined by how they are invited (Averbuch, 2021; Van der Zouwen, 2022). We devoted considerable attention to the invitation process. Participants were invited personally whenever possible, leveraging the networks of the steering committee members. Additional invitations were distributed through the project website and social media channels. We aimed for diversity and representation across higher education institutions, programmes, and roles. For the conferences, we invited the stakeholders grouped by their place in the system of the knowledge triangle, as shown in Table 3.

Set-up of the conferences

Each large group conference required extensive preparation to create a hospitable and inviting setting, and to design instructions that enabled the participants to self-manage their work as much as possible. Every conference was made up of several working rounds. A working round is in itself a small research cycle, applying interactive methods that fit the principles of the LSI. In each round, the participants collect data themselves, self-organise the analyses and interpretation of the results in small groups, and then share the main conclusions in plenary.

The first conference was held in October 2019, six months after the project was officially funded. The main inquiry question asked at this conference was, ‘What will make this project successful?’. About 80 participants were engaged using the large group method of Open Space Technology (Owen, 1997) to create and discuss agenda items for both the research process and desired products. This conference resulted in criteria and areas of concern for the research process, as well as some elements for the scenarios for impactful graduation.

The second conference was held in October 2020. Due to Covid-19 measures, we had to create an online venue with breakout rooms and a shared digital wall to work on. This conference took the form of a mini Future Search (Weisbord & Janoff, 2010), with the main inquiry question, ‘What does your ideal graduate programme look like?’. At the start, the preliminary results of the case studies were presented and discussed. Then the 52 participants were invited to project themselves five years into the future. In small mixed groups of about six people, they created images of their ideal graduation programme, with a written explanation of the key features. In the online environment, every group had its own breakout room and its own section of the central digital wall to display their images. After a break, they presented their image in the plenary room, limited to a maximum of three minutes each. The images generated criteria for the scenarios, and outlines for three scenarios emerged on the spot.

The third conference was held in May 2022, two months before the end of the project. This conference served as a member check, also called participant or respondent validation, in a mixed-method research process (Erlandson et al., 1993; Van der Zouwen, 2010). The main question for inquiry in this member check was, ‘Are the results recognisable, complete enough, and usable for the purpose in your practice?’. This conference also functioned as a start to the dissemination of new knowledge and tools. First, we shared and discussed the conclusions of the case studies and surveys, then the 65 participants got acquainted with the six scenarios we developed in the research teams. They discussed their preferences among the scenarios, using the Scenario Matrix, a tool that can easily be used to discuss values and options for variables regarding graduation programmes. Participants also contributed with corrections and remarks. Next, they experimented with the Impact Canvas, a tool to (re-)design concrete graduation programmes. Figures 4 and 5 provide an impression of the co-creative setting and atmosphere.

Shared ownership for results

During the working conferences, all the results are displayed on the wall in overviews that are accessible to everyone at any time, see for example Figure 4. In this way, the conference report is largely written collectively during the conference. Leadership and responsibility for the process, outcome and reporting are shared. Members of the research team captured everything in photos, made a further summary of the results where necessary, and shared everything in an accessible photo report. The reports were prepared in such a way that people who did not attend the meeting could get a good impression of the activities and results as a vicarious experience (Erlandson et al., 1993; Van der Zouwen, 2022). The yield of each conference was shared as soon as possible, by email with the participants, on the website, and on social media with the wider public.

Emerging research steps: Tool co-design workshops and inspiring examples

During our research journey, some new research steps emerged. Originally, we planned to form co-design teams with stakeholders to develop concrete programmes with impactful graduation trajectories. This turned out to be unfeasible due to long lead times in changing graduation programmes in the UASs. We nevertheless formed co-design teams with a focus on tool development. We started with a co-design workshop where we did try-outs with a variety of tools, to get more of an idea of what type of tools might help stakeholders take steps towards impactful graduation trajectories. Fourteen stakeholders with practical experience participated: four supervisors from the practice, three students, four teacher-supervisors and three researchers. This workshop was prepared and facilitated by two experts in tool co-design. This initial tool co-design session and further try-outs with the steering committee led to a set of selection criteria we applied to select tools on the micro-level (specific trajectory), meso-level (specific programme) and macro-level (graduation programmes). The tools were further developed by the co-design teams, through several iterations of tool versions and try-outs in practice. They were finally presented to a large group of stakeholders in the member check in the third working conference.

Another new research step emerged from the second working conference. Many participants shared that although they were already working on innovation in their programmes, they felt the scenarios with an impact for all stakeholders were too far ahead of their current practice. The idea was born to provide inspiring examples in which programme innovators shared their experiences and the steps they have taken to make graduation trajectories more impactful. In total, 12 examples were collected. Each inspiring example took the form of an article of about 1,000 words. The articles were drafted in conversations with and co-authored by the contact persons. Each article was published as a blog post on the website www.impactvolafstuderen.nl and shared on social media directly after author approval.

Results and impact of the project

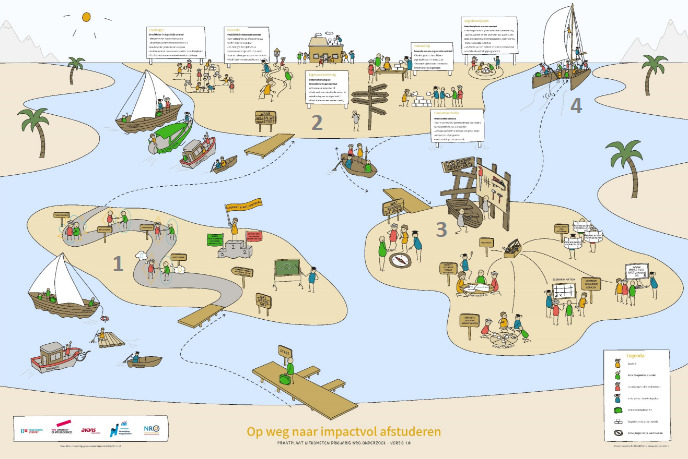

Based on the input from the first two working conferences and the values identified by stakeholders in the case study and surveys, the research team developed six scenarios for pathways that add value for all parties. Tools were developed in the smaller co-creation meetings, and search paths were visualised. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss specifically all the meetings, research steps, and tools. The project’s final report provides a comprehensive description of both the development process and the tools (Munneke et al., 2022). Finally, all results have been summarised in an infographic in the form of a Talking Plate, see Figure 6.

With complex issues, it is usually impossible to establish one-to-one relationships between a project and its impact. Research impact is often diffuse, long-term and potentially difficult to track (Beckett et al., 2018, p. 7). Evaluation is always in terms of ‘did it contribute and was it worth the effort’. Below, we discuss the effects of our example project using the impact levels of Greven and Andriessen (2019). The project contributed to more impactful graduation trajectories through knowledge development, system development and personal development.

Knowledge development

Knowledge development is realised by capturing knowledge in tangible forms. We produced actionable knowledge, with extensive documentation as proof, made available in tools, which will help bachelor programmes take steps towards graduation projects with societal impact. These steps are on the micro-level (concrete graduation projects), meso-level (concrete education programmes) and macro-level (scenarios for graduation programmes with impact). The products are shared in open access in multiple forms, on the website, in blogs and in messages on social media. To promote access, all insights and tools are integrated into one interactive infographic on the website, see Figure 6.

The boats and shipping routes in this infographic indicate pathways for innovation. The infographic guides users along three islands towards a desired situation on the horizon. Island 1 represents what we learned about the current state of affairs in graduation in the system of HEPE. Island 2 presents the six scenarios that produce impactful graduation. Island 3 offers the tools with pathways towards one or more scenarios, and the catamaran on the horizon represents the ideal situation with all stakeholders in the knowledge triangle sailing together on an equal basis.

We contributed to academic knowledge with a better understanding of the complex patterns and dynamics in the knowledge triangle of research, education and professional practice. We delivered a profound overview of the state of affairs in the system dynamics of graduation projects and their added value for society. This knowledge is shared through an extensive research report (Munneke et al., 2022) and in conference contributions and will be shared in academic articles. Workshops are being conducted and planned for further dissemination.

System development

The actual impact of this project is the development of the system, that is, the current practice of graduation from Dutch UASs in the professional field of economics. We collaborated with relevant stakeholders to develop pathways towards six different scenarios for graduation projects that have value for all stakeholders. The LSI process, with the three large group conferences as summits, supported the development of networking and collaboration between the different stakeholders of bachelor programmes in the wider system. It also contributed to awareness in the system of the need for collaboration to deal with complex issues in society.

In general, participants were positive about the co-creation process. From the evaluation of the last working conference, people stated that they took away new insights and inspiration and found the tools useful. Several participants, from all stakeholder groups, said they could see concrete steps for improvement. Program coordinators and teachers who have already been working on innovation found confirmation that they are on the right track. In the years following the project, the circles of engagement need to be widened further, for instance by creating learning communities, workshops and onsite support.

Personal development

Personal development concerns building capacity for co-creative change in the system. In this context, it focuses on developing professional skills in co-designing higher professional education and enhancing competence in facilitating co-creation research. For further personal development, a supportive learning community and follow-up activities, such as workshops and training sessions, are being initiated.

Lessons learned and recommendations

In this section, we reflect on our example project. First, we will evaluate the levels of engagement and the role of the steering committee. Then, we will discuss our lessons learned regarding applying the LSI approach in co-creation research and share our recommendations for enhancing impact.

Sharing leadership and responsibility with the steering committee

When assessing the levels of engagement using the model of change strategies and change capacity of Table 1, we moved between test and co-create. We started with a core team of three researchers, and the academic researchers determined the outline of the design and the budget because of the funding application. The design and the way of dissemination, as well as the methods, were filled in with the stakeholders. In an LSI project for organisational change, all essential decisions regarding design, management and logistics are made together in the steering committee. One or more formal leaders are part of the steering committee to set clear boundaries for the playing field and to engage all board members and managers in the process.

In our example co-creation research project, the three core research team members made the majority of final decisions, as they were formally accountable to the grant provider. The role of the steering committee could have been bigger if they had been part of the consortium from the outset and if responsibility for the process was more equally shared. We recommend starting the process by building a consortium of stakeholders that will also become the steering committee and sharing responsibility and leadership as much as possible in order to build ownership and capacity in the system for ongoing change. This also has consequences for the funding process, as discussed in the next section.

Create a level playing field for all stakeholders in the funding phase

The tightly structured yet informal, non-hierarchical, self-managed way of working characteristic of co-creation (Van der Zouwen, 2024) creates a safe environment for all participants. In the Impactful Graduation project, the student members felt free to express that they understood the central concept of impact slightly differently from the entrepreneurs in their companies, and they, in turn, slightly differently from the teachers, administrators and quality assurance officers. Entrepreneurs could share that they often felt that lecturers did not show much interest in the student interns in their company and that this did not enhance the impact of the internship.

Our steering committee and co-design workshops had comprehensive system representation. However, students and partners from the practice were significantly underrepresented in the three working conferences. Despite a well-designed invitation policy, we could not get more than a few. We think this is mainly due to the unequal positions of stakeholders. Researchers and teachers participated during paid working hours, but we lacked resources to compensate students and entrepreneurs for their time. Research funding cycles often do not support co-creation adequately, primarily due to insufficient time for building trust and a lack of resources for compensating non-academic contributors. We recommend allocating budget and time for consortium building and compensating co-researchers who volunteer their time. Funders should recognise that co-creation research requires additional resources and time to establish a level playing field for all stakeholders (Beckett et al., 2018; Farr et al., 2021).

Adapt methods to fit the right people, addressing as many qualities as possible

After the funding phase, a level playing field must be maintained. Co-creation research demands that researchers do not try to adapt people to the right research methods but adapt the methods to fit the right people (Burns, 2018). Then ‘end-users’, even the most marginalised people, can co-produce new knowledge and change (Begeer & Vanleke, 2016; Burns, 2018; Phillips et al., 2022; Weisbord & Janoff, 2010). In the working conferences and workshops, we worked with embodied inquiry, meaning not only talking but also utilising images and movement to incorporate as many qualities of the participants as possible. Figures 4 and 5 give an impression of the interactivity and energy during the conferences. The joint visualisation of the results in large overviews plays an important role. The co-creation of these overviews is much more than just compiling results and making them visible. People change their focus from talking about co-creation to actually starting co-creation. This way of working facilitates sensemaking by triggering unconscious knowledge. Moreover, the large overviews mirror the messiness and complexity of co-creation (Van der Zouwen, 2024). Our recommendation is to select methods and create conditions that enable everyone needed for success to participate, incorporating the fullest range of human qualities possible. These methods and conditions develop ownership for change.

Widening the circles of engagement continuously

To engage the whole system of stakeholders, we applied thinking in ever widening circles of engagement (Averbuch, 2021). The widening circles of engagement we developed in this project are, starting from the initiative:

-

Initiators: The person(s) who took the initiative for a research project; Tonnie van der Zouwen, Lisette Munneke, Els van der Pool.

-

Sponsor, call: The initiators looked for funding and found a call for proposals of the NRO.

-

Consortium: The initiators formed a consortium, drafted a research proposal, which was granted by the NRO with the review assessment ‘very good’. The consortium comprises four institutions, UAS Utrecht, UAS Arnhem and Nijmegen, Avans UAS, SAC.

-

Steering committee: Approximately 12 stakeholders, a microcosm of the system.

-

Research teams: A core team of the three initiators leading several sub-research teams for specific ‘packages’ in tracks 1 and 2, total number 8 to 10 persons, most of them teacher-researchers.

-

Whole system: Participants of the three working conferences (174 unique persons from 38 organisations), co-design workshop with students, researchers, practice partners, teachers (14 participants), co-design and try-out groups for specific tools (over 200 participants in total).

Since the real impact of the project lies in the actual innovation in the programmes and the collaboration in the knowledge triangle, many more stakeholders need to be engaged after the end of the project. For the ‘follow through for sustainable change’ part in Figure 1, we recommend establishing structures that facilitate an ongoing process of sharing knowledge and initiating change. For instance, invite participants to act as ambassadors in their networks and provide or organise support for onsite implementation, or establish a dynamic learning community as a driving force.

Everything public from the outset

In our example project, the website and social media proved to be effective ways for inviting participation, particularly for the survey research and working conferences, and for sharing information about the research process and disseminating new knowledge and tools. As the process is central, it is important to share it constantly. The aim is to facilitate the flow of the process and ensure that everyone is on the same page as a starting point for the next steps. We recommend daring to share the state of affairs from the outset rather than waiting for the final products. For example, immediately create a website as a living platform with information, invitations, blogs, reports, and tools. Make the results as public as possible and accessible to everyone. Keep people informed about the process in a mix of face-to-face meetings and digital messages. This creates common moments as benchmarks to stay on track in a research process where the paths are made while walking.

Allow for flexibility of the process

Throughout our example project, we had the feeling of ‘shooting at a moving target’; the reality was changing while we were trying to research it. This made the LSI approach even more important. The direct involvement of all stakeholders had an immediate influence on a rapidly changing practice, and the practice, in turn, directly influenced our research. Our research approach thus allowed us to move with the complexity of an ever-changing reality. For instance, the focus shifted from developing new scenarios towards supporting ‘ways of working’ and facilitating ‘searching’. In consultation with the steering committee, it was decided to create search paths supported by tools for the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels in the system.

Continuous attention to LSI principles

Research processes involving the whole system of stakeholders, also called Systemic Action Research, are facilitated processes (Burns, 2014). They require trained facilitators to work interactively with a diversity of stakeholders. As facilitators, the biggest challenge to be faced is learning to work with people as they are and letting them be responsible for their contributions (Weisbord & Janoff, 2010). This requires an open mind and showing up with humility, engagement and curiosity (Averbuch, 2021). Reflecting on our Impactful Graduation project, we underestimated how new this way of working and researching was for many members of the steering committee and the research teams. So, we recommend keeping a steady and explicit focus on the core principles of LSI and their consequences for the co-creation research process, from the start of the meetings with the steering committee and research teams all the way through the project.

Conclusions

Co-creation research can be seen as a collaborative journey where the paths are made while walking. Paying attention to the process of knowledge development as well as awareness of how change may happen is essential for co-creation research to bridge the gap between knowledge development and system development. While co-creation research and participatory change are closely related, they often appear as separate fields in the literature. We presented a model for change strategies showing how the impact of co-creation research can be enhanced by developing ownership and capacity for change throughout the system. The LSI approach can be effectively applied to systems change and knowledge development by achieving high levels of engagement. It requires sharing power, including all perspectives, disciplines and skills, respecting and valuing everyone’s knowledge, fostering reciprocity and mutuality, understanding each other, allowing time to build trustful relationships, and creating space for experimenting with the system. As a consequence, there will always be ambiguity, and things will turn out differently than expected. In practice, fully adhering to all co-creation principles is often aspirational, as not all co-creators have equal power (Farr et al., 2021; Phillips et al., 2022). Working with a steering committee as a microcosm of the system is crucial for engaging the whole system of stakeholders, managing ambiguity, and in developing responsibility and capacity for change within the system.

designing_graduation_programmes.jpeg)

designing_graduation_programmes.jpeg)