Introduction

In November 2021, U.S. President Biden signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) (Congress.gov, 2021b) into law. The law sets aside $65 billion in funding to advance universal broadband access and digital equity. While less was allocated to digital equity than to broadband infrastructure funding, importantly the law recognized, “It is the sense of Congress that . . . achieving digital equity is a matter of social and economic justice and is worth pursuing.” This statement is important because it identifies that digital equity, as it has been recognized in the education field for over twenty years, is a social justice goal that can be understood even beyond the IIJA. As such, there is an opportunity to more fully define the ways in which communities can work together with researchers to develop initiatives to advance digital equity and social justice.

One way to do this is by using participatory action research and participatory design techniques to co-create tools and methods to measure the outcomes and impacts of digital equity efforts. Particularly those efforts led by community-based organizations in support of people most impacted by digital inequities. Community informatics is one area that has emphasized the importance of researchers working closely with practitioners to support the use of information and communication technology towards community-defined development goals (Rhinesmith, 2019). While previous community informatics studies have looked at the use of participatory research and design to address digital inequities in communities, few studies have sought to understand how participatory action research (PAR), as a scholar-activist approach, has been used to advance digital equity and social justice through researcher-practitioner collaborations.

In response to this gap in the literature, the study presented in this paper offers an in-depth reflection on how we used PAR in a previous research project with findings published in a white paper (Rhinesmith et al., 2023a). This current paper seeks to respond to the following research question: What is the value of a researcher-practitioner collaboration using PAR to advance digital equity as a social justice issue? To answer this question, we used our project team’s meeting minutes as a source of evidence. More concretely, this thirty-three-page meeting minutes document provided the evidence that we used to respond to the list of thirty-five questions from Cornish et al.'s (2023) six “prompts for designing a PAR project” (p. 5). This approach provided us with a structured approach to reflect on and articulate the value of using PAR to guide our work together over an eleven-month period. The purpose of this current study was to address a gap in the existing digital equity literature and to more deeply reflect on our collaboration using PAR as a research/practitioner team.

Literature Review

Digital Equity as a Social Justice Issue

The past twenty-five years of research on the “digital divide” (NTIA, 1995) has sought to document the social inequalities in technology access, skills, and outcomes (van Dijk, 2020). While digital equity has been a primary concern within the education field to understand and address inequities in educational technology, the term has been adopted more broadly in recent years due to widespread awareness of the digital divide in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this paper, we subscribe to the National Digital inclusion Alliance (NDIA) definition of digital equity as “a condition in which all individuals and communities have the information technology capacity needed for full participation in our society, democracy, and economy.” Importantly, NDIA adds to this definition the recognition that “when we use the word equity, we accurately acknowledge the systemic barriers that must be dismantled before achieving equality for all” (NDIA, 2024b).

In this paper, we also assume that digital equity is a social justice goal. Social justice is a vision of society in which everyone, regardless of race, class, gender, ability, and other intersecting social identities, has an equal opportunity to participate freely without discrimination, marginalization, or oppression. As Mehra et al. (2017) have described, “In a socially just society, individuals and groups are treated fairly and receive an equitable share of all of the benefits in society” (p. 4218). Toward this goal, people need access to information, which has been recognized by the United Nations (2024) as “an integral part of the fundamental right of freedom of expression.” Because information is increasingly moving into solely digital environments, digital equity can be understood as the social justice goal of ensuring everyone has access to information and technology regardless of their social identity (see Judge et al., 2004). To determine whether digital equity projects are achieving their social justice goals, conceptual frameworks and measurement tools can assist digital equity researchers, practitioners, and policymakers in this process.

Theory of Change

One example of a conceptual framework to help articulate what success looks like in a digital equity program or organization is a “theory of change.” The Annie E. Casey Foundation (2022) defined a theory of change as “the beliefs and assumptions about how a desired change will happen or a goal will be realized.” The Center for Theory of Change (2023) explained that a theory of change is focused “on mapping out or ‘filling in’ what has been described as the ‘missing middle’ between what a program or change initiative does (its activities or interventions) and how these lead to desired goals being achieved.” One tool that researchers, nonprofit organizations, and their community partners can use to measure the outcomes and impacts of their digital equity projects—based on a theory of change–is a program logic model. The W. K. Kellogg Foundation (2004) defined a program logic model in this way,

A picture of how your organization does its work – the theory and assumptions underlying the program. A program logic model links outcomes (both short- and long-term) with program activities/processes and the theoretical assumptions/principles of the program. (p. 3)

A logic model is often used as “a way of visually depicting the theory of change underlying a program, project, or policy” (Frechtling, 2007, p. 21). A logic model is a helpful tool for community-based organizations interested in describing the theory of change underlying a digital equity program or their organization’s work. As a communication tool, a logic model can also help funders, communities, and policymakers see exactly how a digital equity program will achieve its goals and what data will be gathered and analyzed to assess those outcomes.

While logic models come in all shapes and sizes, Frechtling (2007) explained that all logic models contain “four basic components.” These include the following,

-

Inputs. The resources that are brought to a project. Typically, resources are defined in terms of funding sources or in-kind contributions.

-

Activities. The actions that are undertaken by the project to bring about desired ends. Some examples of activities are establishing community councils, providing professional development, or initiating a new information campaign.

-

Outputs. The immediate results of an action; they are services, events, and products that document implementation of an activity. Outputs are typically expressed numerically.

-

Outcomes. Changes that occur showing movement toward achieving ultimate goals and objectives. Outcomes are desired accomplishments or changes. (pp. 21-22)

The University of Kansas Community Toolbox (2024) explains that logic models can be used during various times. These include during a planning stage, an implementation stage, during staff and stakeholder orientations, during evaluation stage, and for advocacy purposes. Therefore, it can be an incredibly powerful tool to establish common language, understanding, and purpose for collective action initiatives, including PAR projects.

Participatory Action Research

Participatory action research, or PAR, belongs to a category of research that has been developed across a wide range of disciplines, epistemological foundations, and social, political, and cultural contexts (Greenwood & Levin, 2007, pp. 6–7). PAR is closely aligned with related approaches, such as “action research,” “participatory research,” “community-based participatory research,” and “participatory community research.” While these participatory approaches may differ in their justification for existence, all generally share an approach to research concerned with the democratization of knowledge production and social change (Stoecker & Bonacich, 1992). In order to achieve these goals, PAR researchers often work closely with “community organizations and members to identify salient and germane issues and topics, and they collaboratively design and implement the research” (Johnson, 2017, p. 4).

Three particular attributes are often used to distinguish participatory research from conventional research: shared ownership of research projects, community-based analysis of social problems, and an orientation toward community action. (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005, p. 560)

This focus on using research to create action and social transformation through participation in the research process, therefore, situates PAR in contrast to more positivist and objective oriented approaches. Researchers using these approaches have identified the problem, research design, and other methodological considerations in advance of their engagement with community members as research subjects to be studied. Through PAR, on the other hand, community organizations and members are invited to participate in every step of the research process, including identifying the research question(s).

Cornish et al. (2023) identified four key principles underlying PAR as a “scholar-activist” project: (1) the authority of direct experience; (2) knowledge in action; (3) research as a transformative process; and (4) collaboration through dialogue. (p. 2). Because PAR stands in contrast to traditional research approaches, described above, the authors explained that researchers may need to build their own PAR-friendly networks and infrastructures to press against any power inequalities due to institutional mismatches and risks of co-option (Cornish et al., 2023, p. 1). PAR is a particularly useful strategy in efforts to address digital inequality because it brings researchers and practitioners together to center local, cultural knowledge, expertise, and wisdom represented by communities most impacted by social and digital inequities. For example, Bozdağ (2024) described the use of PAR in a secondary school in Bremen, Germany to understand “how schools can contribute to reducing digital inequalities focusing on a culturally diverse and socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhood” (p. 135). Bozdağ found that PAR helped to show that “a lack of adequate learning spaces, lack of support and reduced well-being and lack of concentration” (p. 131) were barriers for students in online education during the COVID-19 pandemic.

PAR has been used in a variety of settings globally to address the digital divide. However, in this paper, we argue that there is more room to embrace PAR as a collaborative and mutually beneficial research, planning, and evaluation approach at a moment of unprecedented national investment in universal broadband infrastructure and digital equity in the United States (NTIA, 2022). We believe that implementation and documentation of PAR initiatives over the next five years offer a crucial opportunity to further both the field of digital equity and PAR research and practice. More concretely, while previous studies have used PAR to engage those impacted by digital inequalities (e.g., see Dedding et al., 2021; Goedhart et al., 2022; Ng et al., 2023) few studies have used PAR to co-design a theory of change in researcher-practitioner collaborations working to advance digital equity as a social justice goal.

Research Design

In response to this gap in the literature, this study focuses on an in-depth reflection on how we used PAR in a previous research project that was published in a white paper (Rhinesmith et al., 2023a). In the paper, we presented findings from a participatory action research project co-led by the Digital Equity Research Center at the Metropolitan New York Library Council, where Rhinesmith is the Director, together with Tech Goes Home located in Boston, Massachusetts, where Kang-Le was Advocacy Research Specialist through the project duration and report publication. The purpose of the project was to understand how participatory action research could be used as part of a researcher-practitioner collaboration to develop a theory of change and an evaluation framework to benefit Tech Goes Home, its community, and the larger digital equity field.

This current paper seeks to respond to the following research question: What is the value of a researcher-practitioner collaboration using PAR to advance digital equity as a social justice issue? To answer this question, we used our project team’s meeting minutes as a source of evidence. More concretely, this thirty-three-page meeting minutes document provided the evidence that we used to respond to the list of thirty-five questions from Cornish et al.'s (2023) six “prompts for designing a PAR project” (p. 5) found in Appendix 2. This approach provided us with a structured approach to reflect on and articulate the value of using PAR to guide our work together over an eleven-month period. The purpose of this current study was to address a gap in the existing digital equity literature and to more deeply reflect on our collaboration using PAR as a research/practitioner team.

We begin this section by providing additional details on the research site where the PAR project took place, as well as additional background on how the research published in the white paper started. We then introduce the analytical framework that we used to answer our research question for this current research project. We conclude with a brief critical reflexivity statement, which we hope will help the readers to understand our positionality as two of the five people on our researcher-practitioner PAR project team who led this current paper’s study.

Research Site and Project Background

Tech Goes Home (TGH) is a nonprofit that has been working to advance digital equity since 2000. Since its inception, TGH has helped tens of thousands of people in Massachusetts gain access to the digital world. TGH’s approach to advancing digital equity is grounded in what they deem the three “legs of the stool”: skills, devices, and internet. Every TGH learner who completes 15 hours of digital skills training through a community partner organization earns a new computer or tablet, and, if needed, a year of TGH-paid internet. In keeping with an understanding of digital equity as a social justice goal, TGH deliberately partners with communities most affected by the structural injustices at the root of digital exclusion. Rather than keeping in-house instructors, TGH trains staff at partner organizations with established roots in the communities they serve to deliver culturally-responsive digital skills courses. TGH partners are organizations–libraries, public schools, nonprofits, community health centers, senior centers, and more–who serve these populations, have a built trust among their communities, and whose work can be elevated by providing digital access.

In a recent survey conducted by Connect Humanity (Herschander, 2023), nearly 80 percent of nonprofits surveyed said that a lack of internet access, tools, or skills among their staff or those they serve limits their work, while 90 percent considered the internet critical to their work. TGH addresses this gap by equipping staff at TGH partner organizations with the hardware, resources, and training needed to deliver digital skills courses and connect those they serve. Of all TGH learners, 93% live in households that are considered “very low income” (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2023), 86% identify as people of color (including 39% who identify as Black and 30% who identify as Latinx), 60% speak a primary language other than English, and 35% of adult learners are unemployed.

TGH’s digital equity programming aims to amplify work that advances social justice and promotes broader outcomes for learners in areas including education, employment, healthcare access, reduced recidivism, immigrant rights, and more. As part of ongoing efforts to increase organizational capacity to meet this goal, TGH sought to better understand, evaluate, and represent their programs. It is within this context that they engaged in the research collaboration detailed in this paper. The hope was that the findings from this research project could also be used to help inform the broader digital equity field in the context of historic levels of federal investment.

PAR Project Background

In April 2023, Tech Goes Home was awarded a grant from American Rescue Plan (Congress.gov, 2021a) funding allocated for digital equity. This grant, the largest single grant in TGH’s history, enabled the organization to pilot a new subgrant program and expand programming to 13 new municipalities across Massachusetts. As a government grant, it also required TGH to report information to validate the organizations’ programmatic approach and demonstrate the impact of such an investment. TGH was thus invested in building a data-based model that legitimized their work for new stakeholders and that ensured key impacts and components of their work could be identified, scaled, and evaluated. Organization leaders hoped a theory of change could guide TGH’s own expansion, establish TGH as a leading voice in digital equity evaluation, and lay out a roadmap for other digital equity organizations to better achieve their goals.

TGH had a relatively robust existing evaluation infrastructure and had been using surveys to collect feedback from program participants for more than a decade. These surveys illuminated impacts of digital equity programming across areas including health access, confidence, education, and employment. More detail on the TGH evaluation process can be found in the authors’ white paper (Rhinesmith et al., 2023a). However, the reality of the digital divide and of TGH’s partnership model meant that impacts were diffuse across populations, geographies, and issue areas. TGH sought to create a theory of change that would not only clarify their programs’ key impact areas and steward strategic growth, but also help the organization to better understand the communities they served.

Although proud of their decades of work and impact, the organization still sought to improve their program to the benefit of learners and instructors and acknowledged their lack of expertise in community-centered research methods. In the case study explored herein, TGH engaged the Digital Equity Research Center (DERC) to work in tandem to develop a theory of change. To ensure that the community remained at the center of TGH’s work, the organization felt such a theory of change could only be built and adopted with feedback, partnership, and buy-in from TGH learners, instructors, and partners. In the TGH-DERC case, and for other community organizations who may also benefit from working with researchers to co-design a theory of change (see Appendix 3), participatory action research emerges as an ideal approach to research in support of this work.

The white paper presented findings from the analysis of qualitative data, gathered in our previous study, which included interviews and focus groups. A total of 43 people participated in the participatory research project. Participants included representatives of the following populations: (1) learners in Tech Goes Home programs; (2) instructors who teach Tech Goes Home courses at their community-partner organizations; (3) Tech Goes Home staff, managers, and directors; and (4) representatives from peer digital inclusion and digital equity organizations from across the U.S. who shared their experiences and insights. As we described in the report, staff at the DERC working closely with staff at TGH (hereafter referred to as “the research team”), utilized PAR methods throughout the entire project.

For this present study, we provide a more in-depth investigation and analysis of our research collaboration to describe how PAR, as a participatory research strategy was useful to us in our project and how it could be useful to other digital equity researchers and practitioners to advance digital equity and social justice more broadly.

Data Collection and Analysis

Using Meeting Minutes as the Dataset

To answer the research question, address a gap in the existing digital equity literature, and to more deeply reflect on our collaboration using PAR as a research/practitioner team, we decided to use our research team’s “Running Notes” project meeting minutes as the source of evidence in this current study. The thirty-three-page meeting agenda provided the evidence that we used to respond to the list of roughly thirty-five questions included in Cornish et al.'s (2023) six “prompts for designing a PAR project” (p. 5). In other words, we used the meeting agenda as a data source from our project that we could use to review the list of (1) “attendees,” (2) “agendas,” (3) “meeting notes,” and (4) “action items” found in this document.

Analytical Framework

In analyzing our meeting minutes document as a data set for this research, and as a way to further delineate our process for our paper, we used Cornish et al. (2023)’s “six PAR building blocks” summarized in Table 1 below and described further in Appendix 2.

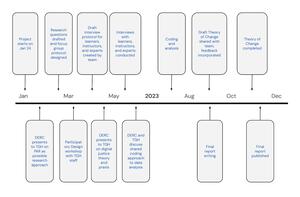

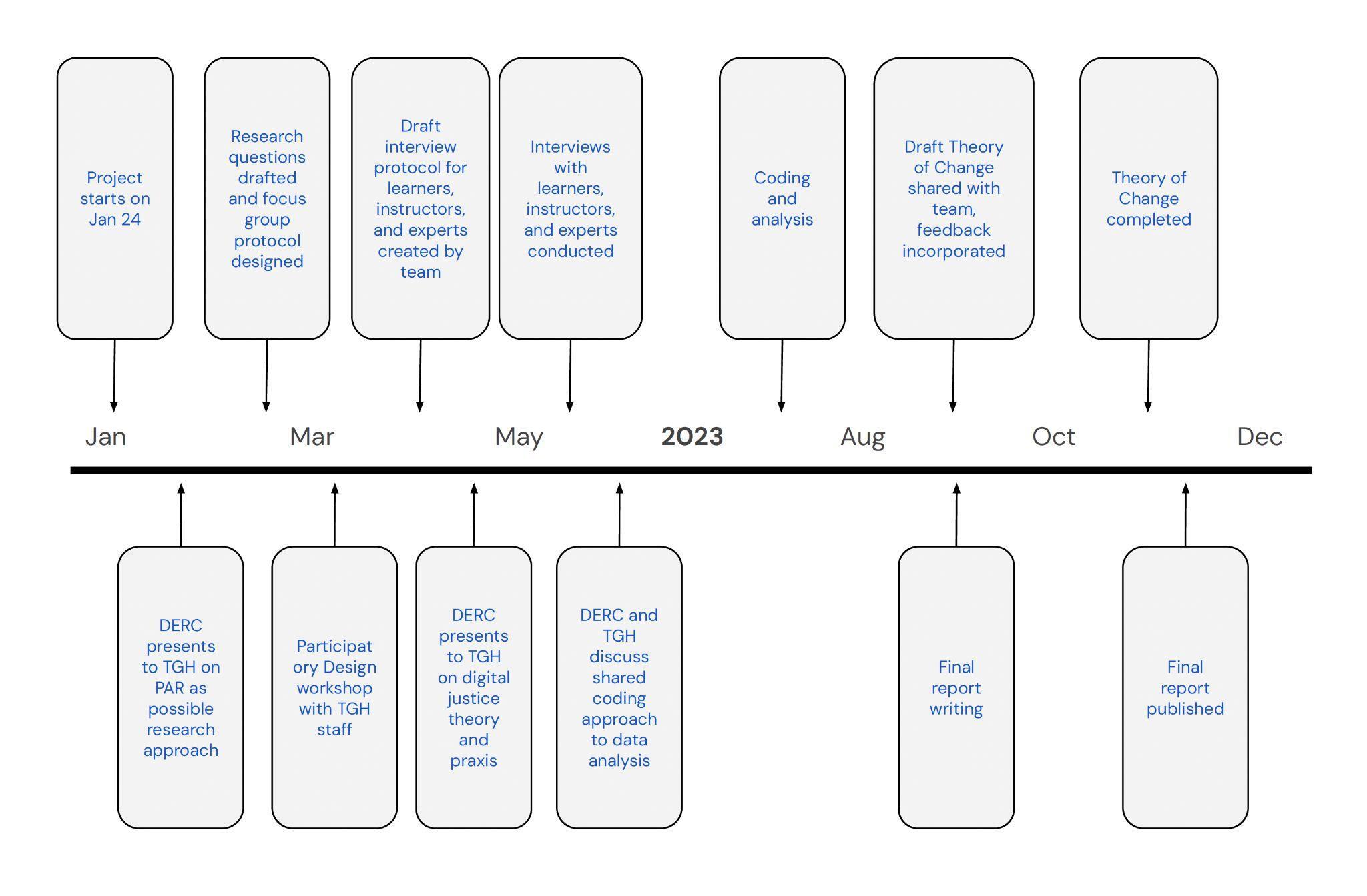

Rather than necessarily coding each part of the meeting minutes document, we used the document to answer Cornish et al.'s (2023) thirty-three questions, as we describe further below. Using this document as a source of evidence provided us with a structured approach to answering the questions by reflecting on and understanding the value of using PAR to guide our team’s work together over an eleven-month period from January - November 2023. A more in-depth timeline is available in Appendix 1.

We began this process of analysis by changing Cornish et al.'s questions from present to past tense and went through the reflective exercise of answering, to the best of our ability, the questions asked in Cornish et al.‘s paper. The two lead authors on this paper divided up our analysis of the meeting minutes document by assigning questions under each “building block” evenly between us. For example, as the lead author I answered the following four questions under the fifth building block titled “collaborative data analysis”: "How do we facilitate and record participants’ collective critical interpretation and analysis? How do we divide up tasks of data interpretation between various team members and then bring them together? How do we plan to produce eventual project findings and messages? Can we state our key findings on one page, and our messages for different audiences?"

To answer these questions, I reviewed the entire “Running Minutes” document and noted where there were particular insights to help respond to these questions. For example, in answering the question about how our research team divided up tasks of data interpretation between various team members and then bring them together, I reviewed our meeting minutes and noted that on July 27, 2023 the project team assigned the following data analysis tasks:

-

"Coding–what’s been done already, what needs to be done?

-

Division of responsibilities, set timeline

-

Colin’s proposal to team:

-

Malana: instructor coding & focus group excerpts/analysis

-

Sangha: national org coding & focus group excerpts/analysis

-

Colin: finish remaining interviews & draft report writing

-

-

Decision on first/second level coding

-

See Saldaña chapters

-

Colin will review all transcripts and decide which approach would be best"

-

-

-

On August 10, 2023, our team shared insights from our coding process with each other and set aside time during our meeting to, as the meeting minutes described, have a “coding check-in” to discuss “What other questions do we have?” The results of this analysis, taken together, served as the main findings in the next section and the basis upon which we share our assertions about the value of researcher-practitioner PAR collaborations in digital equity projects.

Critical Reflexivity Statement

As the two co-authors of this paper, we represent two different positionalities. By positionalities we refer to critical feminist scholarship that has highlighted the importance of indicating “the social location of the researcher—in terms of gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, religion, age, ability, citizenship status, and more—and its effects on the research” (Jackson et al., 2024, p. 6). By identifying our positionalities, we hope it will provide the reader with an increased understanding of how our social identities, as well as some of our personal and professional experiences, have shaped the assumptions and knowledge that we bring to this research project.

The first author on this paper identifies as a middle-age, white, queer, cisgender man from a middle to upper-class background with a Ph.D. in library and information science and generalized anxiety disorder. The second author identifies as an Asian American, heterosexual, able-bodied, cisgender woman from a middle-class background with a Bachelor’s degree. The two of us together represent a small part of a larger research team that worked closely together on the year-long PAR project co-led by Tech Goes Home and the Digital Equity Research Center located at the Metropolitan New York Library Council. As we explain in this paper, we report on the participatory research process that we co-led and co-utilized which led to the findings described in our report published by Tech Goes Home in November 2023.

As the first author, I brought my academic background in community-based and participatory research to this project. I certainly came to the project with more power and privilege than others on our team. This is because of how I show up in the world as a white man and what this identity has afforded me in both earned and unearned ways. My hope is that through our research team’s shared values rooted in mutual respect, benefit, and care for each other as colleagues and collaborators that I have helped to play at least a small role in creating a more level, open, and supportive space for our research team to work together in a meaningful way. In addition, I have actively tried to follow and be held accountable to the principles that guide our Center’s work, which are rooted in an asset based, power aware, respect focused, and justice centered approach.

As the second author on the paper, my responsibilities included building relationships with TGH community members and advancing digital equity policy, alongside research production. My position as a representative of the organization may have facilitated greater trust between the researchers and community participants, but in other cases may have constituted a power imbalance that could keep participants from discussing negative experiences. I worked with the rest of the team to intentionally address this potential disparity throughout the research process (see more in the “Research Design” section). I brought my own insights and expertise to the analysis, but shared findings with and incorporated input from TGH team, community, and digital equity field experts to mitigate bias resulting from my investment in our research findings. As a non-Black person of color from a middle-class background engaging with community participants who often held fewer unearned privileges, I was careful to stay rooted in TGH’s approach to digital equity as a racial and social justice issue (Tech Goes Home, 2024), as well as our research team’s equity-centered and participatory approach.

Research Findings

This section details the findings from our use of the “Running Notes” meeting minutes document to answer the thirty-five questions found in Cornish et al.'s (2023) six “building blocks” framework for designing PAR projects. As representatives from each of the two organizations that co-led the research previously published in our white paper (Rhinesmith et al., 2023a) for Tech Goes Home, we did our best to accurately represent this collaborative research process on behalf of our entire research team who were not available to participate in writing this paper. The titles of each section represent each of the six building blocks in the Cornish et al. (2023) framework.

Building Block #1. Building Relationships

There were several ways that using a PAR approach helped our research team to build the relationships that guided our project. In this section, we describe how PAR provided a framework to help us critically reflect on the process that we used to consider the community boundaries and composition that existed, as well as the existing relationships that helped to drive the overall project. It also helped us to consider our own positionalities and power relations between the research team and members of the community who also participated in the research project to help develop a theory of change for TGH found in Appendix 3.

In designing a PAR project, Cornish et al. (2023) ask collaborators to consider the following questions: “What are the boundaries and composition of the community as defined for this project and what relationships already exists between university [researchers] and community?” (p. 5). In our research project, collaboration included, broadly, researchers from DERC, researchers from the TGH team, and representatives from the TGH community. In the context of this project, that community included the full organization staff, select instructors employed at community partner organizations, learners who had graduated three and five years prior, and leaders from other digital equity organizations. As discussed above, both the organization and the research team felt strongly that a theory of change could only be built with input from the communities TGH served. These populations were identified by DERC and TGH through an exhaustive brainstorm of potential stakeholders and perspectives. The team also sought to engage research participants whose own identities were representative of the overall demographics of TGH learners.

In response to the question, “what are the implications of the positionalities and power relations in the community?” (Cornish et al., 2023, p. 5), learners and instructors had records of previous engagement with TGH, having received training by TGH team members, TGH devices and internet, and years of communication from the TGH team. In many cases, this engagement built trust between the researchers and community members, increasing participants’ willingness to engage in the research process. However, though instructors were not employed by TGH and courses were provided free of charge to learners, we were cognizant that community members may be hesitant to provide critical feedback for fear of their comments affecting their ability to receive services from TGH. We attempted to address this concern by only including learners who had already graduated their TGH program and received their device. We included the following language in a written consent form, which was distributed in both English and Spanish:

There will be no penalty whatsoever for refusing to participate or withdrawing at any time during the study process. In addition, withdrawal or refusing to participate in this study will not affect your relationship with Tech Goes Home or Metropolitan New York Library Council in any way whatsoever.

We also included the following in our facilitator protocol, which was read out loud at the beginning of each focus group:

We also want to make clear that we want to hear as much as you’re willing to share about your experiences with our courses. It will be really helpful to hear about what was most useful, what wasn’t as useful, and where we could improve. There will be no negative affect on you, and nothing you say will affect your relationship with Tech Goes Home.

The TGH researchers did not have previous experience using PAR, although the second author had previously facilitated focus group interviews in multiple languages. The DERC team created learning materials on PAR and facilitated a live training session for the TGH researchers.

Building Block #2. Establishing Working Practices

Using a PAR approach in our research to develop a theory of change for TGH encouraged us to critically reflect on the decision-making, implementation, and leadership roles established during the project and its influence on the final theory of change. In this section, we present findings from our analysis to describe the work practices that our research team developed and its role in supporting the overall PAR project. We conclude this section with a discussion of how our researcher-practitioner team processed any differences, tensions, and power relations within our research team.

Cornish et al. (2023) invite collaborators designing PAR projects to consider the following questions: “What resources are available for the project (staff capacity and funding) and how are decision-making roles, implementation roles and responsibilities to be distributed?” (p. 5) Tech Goes Home provided internal staff capacity as well as funding to hire the team at the DERC to participate through a grant from the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation. At least two staff members from TGH and two members from the Digital Equity Research Center were present most weeks during the year-long project. This ongoing weekly time commitment played a significant role in keeping the project moving forward to achieve the goals outlined in our shared scope of work document. In addition, TGH provided funding to support the inclusion of the perspectives of staff during our participatory design research and other data gathering processes, and funding to compensate community members for their participation in the two focus group sessions that were held at Boston Public Library branches.

Using a PAR approach helped to ensure that decision-making roles were evenly distributed among the team members. Evidence of this shared decision-making process can be found in our Running Agenda document. For example, in the following meeting minutes from June 15, 2023: “Colin will review all transcripts and decide which approach would be best. Colin & Sangha will work on getting Dedoose downloaded.” In another example, the group shared decision-making around who would ask the questions during the focus group sessions: “Determine who will ask what questions. [TGH and DERC researchers] will decide via email.” These decisions often led to a shared process for determining who would implement and ultimately be responsible for which part of the project.

The Action Items section at the end of each meeting also provided clear details on the implementation roles and responsibilities for each part of the project, as the following excerpt from our February 16th meeting in the early stage of our PAR project shows

Action items:

DERC will send consent intro form

- [TGH] will draft a FAQ to explain the consent form. Aiming for the week after NDIA (first week of March)

TGH team review the Community Toolbox resource

TGH & DERC: Read through & think about focus group questions

DERC: draft overarching research question

For next meeting:

Circle back on focus group questions

Let’s start to identify key PAR values/statements to guide the work

Circle back on Colin’s PAR presentation

These action items also helped structure our work in-between meetings and keep us on track toward meeting our project deadlines and goals.

In response to the question, "how will meetings be structured, chaired and prepared for? (Cornish et al., 2023, p. 5), our “Running Agenda” document, which provided the main data set for our analysis in this study, also provided detailed information about the structure of each meeting. This included any sections of the meetings that were led by different research team members. For example, this excerpt from our May 4, 2023 meeting agenda perfectly described how the structure of our meetings facilitated collaboration between the two organizations on the research team:

-

TGH and DERC: Discuss TGH data

-

DERC: Review logic model template [draft] with TGH team

-

DERC and TGH: Finalize interview protocols

-

TGH: Present ideas about instructor interview structure

In terms of preparation, most agendas were prepared by the TGH team with additional items added by members of the DERC team. One can look back at the history of the document to see how meetings were structured by the team members.

Using PAR for our digital equity researcher-practitioner project was also helpful for establishing “principles for ‘ownership’ of findings, anticipated uses and sharing findings” (Cornish et al., 2023, p. 5). For example, because our goal was to make sure the project could be useful both to TGH internally (i.e., creating the theory of change to inform internal data gathering and program evaluation) and to the broader digital equity field externally (i.e., final research report), there was a sense of shared ownership of the research, including the findings that could be useful and shared in a broad context. There were two specific ways in which this was handled through our collaborative research project.

The first deliverable at the end of Phase 1 included a landscape analysis, identification of outcomes & impacts, and key metrics for the theory of change. The final deliverables for the project were a Theory of Change for TGH plus a white paper with findings to benefit the broader digital equity community. In addition, our team members from the DERC created a separate internal document for TGH with key recommendations and learnings from our project.

The findings included in the final white paper (Rhinesmith et al., 2023a) were shared more broadly with the National Digital Inclusion Alliance, whose mission is to advance digital equity by supporting community programs and equipping policymakers to act (NDIA, 2024a). The white paper was also featured on a podcast hosted by Connected Nation (2024), which is a national nonprofit based in Bowling Green, Kentucky that has worked in the broadband and related technology space for more than 20 years. TGH staff and a community representative also presented findings from the white paper on CityLine (2024), a local televised broadcast that airs on WCVB in Boston, Massachusetts.

Cornish et al. (2023) ask those interested in designing a PAR project to answer the following question: “How will we process emergent differences, tensions or power relations within the team?” (p. 5). One of the ways that our team worked to recognize and challenge existing power relations during the project was to share ownership and control over the decision-making and actions taken to advance the project’s goals. This was apparent in the examples found in the sections of our meeting minutes presented above. Also, because our team met weekly, we worked to develop a mutually beneficial relationship that helped to level the inherent power dynamics present due to differences in age, gender, race, ability, and other social identities. We attempt to describe how the two of us, as co-authors of this report, addressed these power dynamics in our reflexivity statement above.

Building Block #3. Establishing a Common Understanding of the Issue

Cornish et al. (2023) explained that in order to establish a common understanding of the issue to be addressed through a PAR project, it’s critically important for the research team to develop an “agreed statement of the issue and the project’s aim or research question” (p. 5). As the lead author of this paper with background and expertise in participatory research methods, I was interested in gaining a deeper understanding of how PAR could be used to develop a digital equity theory of change with a non-profit organization partner with deep expertise and knowledge of digital equity and social justice work. Before this project started, I had experience working with TGH in my former role as an associate professor of library and information science. My graduate students and I had an opportunity to develop a community engagement project with TGH where my students developed a final unpublished report, titled “Measuring the Impact of Digital Literacy: Tech Goes Home Programs in Greater Boston.” This experience provided my students and I with a deeper understanding of the issues that TGH has been working to address over many years. Through working closely together on the design of the research project, we were able to develop a mutual understanding of TGH’s desire to develop a theory of change to help inform their evaluation efforts. The relationships and experiences of members of both teams helped to establish “the common statement of the project’s aims and/or research questions” (Cornish et al., 2023, p. 5). In our case, the mutually agreed upon research question that guided the development of our theory of change was the following: “How can participatory action research be used to develop a theory of change and an evaluation framework to benefit Tech Goes Home, its community, and the larger digital equity field?”

Building Block #4. Observing, Gathering and Generating Materials

Cornish et al. (2023) introduced several questions to help research teams determine the following three steps in their PAR projects. These questions included the following: "What data generation or data collection methods do we plan to use? What ethical issues may be raised by our methods; what ethics training do we need? What training in technical or professional skills do team members need? How will the team incorporate reflection and iteration of our process?" (p. 5). In this section, we present answers to these questions based on the analysis of our data set used for this research paper. During the final part of this section, we describe the value of using PAR particularly as way to critically reflect on our findings, receive feedback on what our team members learned through our analysis, and ensure the right people from the community were involved in the project.

In response to questions about our data collection, as we described in the “Appendix I. Research Methodology” section of our white paper (Rhinesmith et al., 2023a), we held three focus group sessions with learners enrolled in TGH’s programs. Two of these focus groups took place at the Codman Square Branch of the Boston Public Library (BPL) in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston. The final focus group took place at the East Boston BPL branch and was facilitated and conducted in Spanish. TGH courses are designed to be accessible and responsive to the needs of learners who enroll; nearly 4 in 10 courses are taught bilingually or in a language other than English, and 27% of learners speak Spanish as a primary language. As we also explained in our white paper, both library branches have hosted numerous TGH courses and are situated in predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods. Generally, the demographics of learners who participated in our study aligned with overall demographics of TGH survey participants listed in the 2022 Impact Report (Tech Goes Home, 2022).

In addition to the focus groups, our team conducted a total of seven instructor interviews. Two out of the seven instructors identified as men, while five identified as women. Two out of seven instructors worked for organizations outside the Boston Metro Area in Gateway Cities in other parts of Massachusetts. The demographics and locations where the instructors worked were also included in the methodology section of our white paper. A total of 16 TGH staff members also took part in our participatory design workshop, mentioned in the timeline in Appendix 1 and further described in our white paper. As it was important to get feedback from across the organization, an effort was made to include people from various departments, which are detailed in Table 2 below.

The final category of participants included what we called “peer organizations.” A total of eight peer organizations from across the country participated in interviews. An effort was made to include organizations representing a diverse range of geographies and service populations. Organizations primarily focused on grant-making or research were excluded in favor of those organizations with digital inclusion service models similar to TGH. Five out of the eight organizations were located in the Southern United States.

During our weekly research team meetings, we co-designed each of the three interview protocols for the project. These included one focus group protocol for TGH learners, one interview protocol for TGH instructors, and one interview protocol that we used in our conversations with representatives of peer organizations. Our research team used a portable recording device to record the meetings, which we later transcribed using Scribie.com. The participatory design workshop with TGH staff produced notes that were analyzed and reported back to the entire team for discussion and collaborative analysis that helped to inform the final theory of change.

In response to the question, "What ethical issues may be raised by our methods; what ethics training do we need?" (Cornish et al., 2023, p. 5) our research team hired an independent Institutional Review Board (IRB) to conduct a human subjects research exemption review. The study was approved in accordance with the Code for Federal Regulations for exempt research (National Archives, 2024). As such, the IRB included the following details in our letter for approval:

-

This determination does not include, and should not be taken to imply, any approval of the study or its consent process or form.

-

Researchers are advised that they should adopt the principles in The Belmont Report or an appropriate ethical code in the conduct of their studies.

-

Researchers are advised to maintain excellent communication with institutional and site authorities.

-

All researchers must comply with relevant state and federal regulations.

This letter was shared with all the members of the research team at TGH and the DERC.

Because the research team had previous experience conducting interviews and focus groups, there wasn’t any formal training needed in our data gathering process. Once the data were collected, the team at DERC did provide training on how to use Dedoose, a cloud-based software platform for qualitative and mixed methods data analysis. DERC also provided a review of qualitative coding methods, and the research team worked collaboratively to identify an approach best suited to our project needs (more detail in “Data Interpretation and Roles for Analysis”). A further description of this collaborative analytical process is described below.

Cornish et al. (2023) invited PAR project designers to describe how their teams will incorporate reflection and iteration of our process. In response, our weekly meetings provided an excellent opportunity for ongoing reflection and iteration on our data gathering processes. For example, as our team conducted focus groups and interviews, each team member who served as lead or co-lead for these activities had ample opportunities to share back, discuss, and receive feedback through group discussions during our research team meetings. We shared what we were learning from each of the data gathering activities to ensure that we were being inclusive in our recruitment of research participants. Our team also shared findings with representatives from the TGH team at three key points during the project, soliciting input in multiple formats including written comment, online surveys, and live focus groups. Data from these reflections were incorporated into multiple iterations of our project deliverables. This ongoing open communication was essential to ensure that our participatory research project was grounded in ongoing reflection and iteration.

Building Block #5. Collaborative Analysis

Cornish et al. (2023) explained that in order “for the results and recommendations to reflect community interests” in PAR projects, “it is important to incorporate a step whereby community representatives can critically examine and contribute to emerging findings and core messages for the public, stakeholders or academic audiences” (p. 7). This is one area that we are particularly proud of related to how we engaged TGH staff and community members to ensure that the analysis of their research contributions ended up being reflected in the final version of TGH’s digital equity theory of change. More concretely, Cornish et al. (2023) presented several questions that are helpful in designing PAR projects to ensure that “key findings and messages for different audiences” (p. 5) are agreed upon by the research collaborators. In this section, we present findings from our analysis of our meeting minutes document to describe how our collaborative data analysis reflected these PAR principles.

There were several ways that our project team worked to ensure that the insights and feedback from project participants informed the overall theory of change developed through this research. More concretely, we conducted interviews and focus groups with learners, instructors, and partners with TGH to gain their insights, as well as from other digital equity organizations interested in assessing the outcomes and impacts of their work, which we used to help inform the research. The participatory design workshop and subsequent follow-up feedback sessions helped inform the final version of the logic model.

In dividing up “tasks of data interpretation between various team members and then bringing them together” (Cornish et al., 2023, p. 5) members of our research team collaboratively coded the qualitative data, analyzed for our white paper (Rhinesmith et al., 2023a), in Dedoose using what Saldaña (2016) called “holistic coding.” As we described in the “Research Methodology” section of our white, Saldaña described holistic coding as “appropriate for beginning qualitative researchers learning how to code data and studies with a wide variety of data forms” (p. 166). This was particularly useful for our team, which had various levels of experience with coding qualitative data. This approach can also be useful, Saldaña explained, when the researcher already has an idea of what to investigate (i.e., learner articulated outcomes of digital skills training). This approach allowed our research team to apply outcomes-based codes to larger blocks of data as a first-level or initial coding method.

In addition to this coding process, which led to the codes presented as examples in our white paper, our research team identified outcomes-based codes defined by TGH staff that were used in comparison with what we heard from focus group participants. The purpose was to gain multiple perspectives to inform our research. Examples of staff-defined learner outcomes codes can be found in Appendix 1 of our white paper. Our weekly meetings also provided our research team with opportunities to talk through any of the codes and to answer any questions that arose during the coding process.

Members of our research team also co-designed plans to share findings from our PAR project. For example, each team agreed that findings should be shared throughout the process with every stakeholder group. Discussion about how and when to share which findings began in our first weekly meeting and continued throughout the project. As professional researchers, DERC led a conversation about sharing a draft of our white paper with participants who were directly quoted. As community-based researchers, TGH led a conversation about sharing a draft theory of change with all TGH staff who participated in the research process. Language communicating key findings for specific external audiences, including the digital equity community and social media followers, was shared among the researchers for approval before publication.

Lastly, Cornish et al. (2023) suggested that in designing PAR projects, research teams should aim to state key findings on a single page and share messages for different audiences (p. 5). In our project, we created a short summary of our research findings, which the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society graciously published to help share the white paper with relevant stakeholders in the digital equity field, including researchers, practitioners, and policymakers (Rhinesmith et al., 2023b). This summary was also shared in various online forums, including LinkedIn, X, and relevant listservs. We also highlighted key findings for the digital equity community to share with members of the National Digital Inclusion Alliance, a coalition of organizations from across the country engaged with digital equity, technology, and broadband development issues. Finally, TGH and their communications associates distributed a press release which pulled out findings for policymakers and digital equity organizations to share with the TGH community, philanthropic partners, and media representatives.

Building Block #6. Planning and Taking Action

In the sixth and final building block, Cornish et al. (2023) provide a series of guiding questions to assist those designing PAR projects to develop collaborative action steps to ensure that social change results from collaborative research endeavors. As the second author, my goal in undertaking this collaborative project was to create tools which would allow TGH to center the voices of community members as the organization grew and developed both its program components and geographic service area. I hoped that the TGH digital equity theory of change found in Appendix 3 would also be useful to policymakers and municipal governments and could lay out a roadmap for entities tasked with digital equity program planning and evaluation to meaningfully incorporate the perspectives of people with lived experience of the digital divide.

As the first author, my goal for this project was to use my background and expertise as a community-engaged and participatory researcher to develop a mutually beneficial partnership with TGH that could benefit their organization, learners, and instructors. I also hoped that our participatory research project could serve as a model for other digital equity organizations interested in working together with researchers to develop a theory of change for their organizations.

To achieve the above goals, we first prioritized buy-in and meaningful adoption of our key findings by the Tech Goes Home team. We held multiple live information sessions and conducted one on one conversations with key team stakeholders. We also engaged their strategic planning committee to ensure that our research findings informed the organization’s ongoing ten-year strategic planning process. We wanted to communicate our findings to all those affected by the digital divide, and so we published a press release informing funders and key stakeholders in written and broadcast media about our research report and theory of change. We further engaged broader audiences through appearances on local news channels and digital equity podcasts where we relayed key findings from our participatory process.

To communicate our findings to the digital equity field, we released announcements on digital equity community listservs and centered our findings in a presentation at an annual digital equity conference, attended by representatives from internet service providers, digital equity advocacy organizations, libraries, nonprofits, researchers, municipal planners, and other entities. In the geographies TGH had an existing footprint in and was targeting for expansion, our findings for policymakers helped to elevate the organization’s name recognition. We worked with the TGH advocacy team to incorporate these findings into presentations and printed materials for legislators and municipal staff. Our findings on centering the community voice were included and emphasized in written comments on the Massachusetts State Digital Equity Plan and proposed plan for BEAD deployment submitted to the Massachusetts Broadband Institute.

We were able to engage a broad base of stakeholders at this scale due to the input and expertise of TGH leadership, staff, strategic planning and communications consultants, and community members. In keeping with their original intentions to elevate their existing work by leveraging the expertise provided by researchers, TGH also recognized the value of researcher-practitioner collaborations and dedicated evaluations work. Findings from this collaboration helped solidify TGH’s commitment to hiring a Chief Learning and Evaluations Officer and building out a full evaluations team to continue the work described herein.

Discussion

We now turn to discuss the ways that our findings responded to our research question about the value of a researcher-practitioner collaboration using PAR to advance digital equity as a social justice issue. We begin by describing how our project yielded several benefits, before discussing some of the impacts that results from our work together.

Benefits

There were three benefits of our researcher-practitioner collaboration using PAR to advance digital equity as a social justice issue. The first was that the approach allowed TGH to engage in a research project that aligned with the organization’s values of centering community voice or the “lived experiences” of our research participants. As Kidd and Kral (2005) described, through participatory action research,

Researchers learn something about the lived experiences of the participants: how they perceive problems and strengths, ways that they can know about each other and their community, and how change is experienced, as both active agents and those receiving the benefits of positive change. (p. 189)

By centering the lived experiences of learners in TGH programs, community members contributed to the development of a logic model to more accurately and fully reflect what program success looked like from the perspective of community members. Because the participatory research design included the perspectives of multiple stakeholders in TGH programs (i.e., learners, instructors, and staff), the lived experiences of each stakeholder were reflected in the final version of the TGH theory of change. TGH was thus equipped with an iterative, community-informed tool to evaluate the success of programs and guide future curriculum development. This approach also helped to advance digital equity as a social justice goal because of the way the logic model ensures that TGH programs serve the information and technology needs of the community regardless of their social identities (see Judge et al., 2004).

The second benefit was that our PAR project helped to build a shared understanding of the organization’s work across departments and levels. The participatory design workshop, held early on in our project, provided staff across the organization with an opportunity to come together and share their work, including what success looks like to them. This process helped to break down silos between departments, allowing staff to connect the dots and see the whole picture of the organization’s work. The workshop also helped to clarify activities, outputs, and outcomes for the logic model as represented by different roles within the organization.

Third, our researcher-practitioner collaboration produced a logic model that equipped the TGH team with a customizable tool to use in their work with specific populations to advance digital equity. In other words, after the draft version of the digital equity logic model was shared back with people across the organization, it became clear that parts of the overall organization’s theory of change, represented by the logic model, could be useful for specific programs within the organization. Separate, smaller, and more focused logic models therefore could be developed and utilized for purposes including grant applications, advocacy with legislative bodies, and conversations with potential partner organizations.

These three benefits also provide evidence of the attributes often used to describe the value of using participatory research, as opposed to more conventional research approaches mentioned earlier in this paper (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2005, p. 560). For example, through our researcher-practitioner collaboration we established a strong shared ownership of our research project, which is evident both in producing our white paper (Rhinesmith et al., 2023a) as well as the additional analysis presented in this research paper. By emphasizing the digital equity needs of TGH learners and the teachers who support them, our PAR project emphasized a community-based analysis of digital inequity as a social problem. Lastly, our project was oriented “toward community action” in the way that Kemmis and McTaggart (2005) described, particularly in that our digital equity theory of change serves as a living document that guides TGH’s digital equity programs and services, including their approach to evaluation.

Impacts

In addition to these benefits, there have already been several impacts from the PAR project described in our white paper (Rhinesmith et al., 2023a), which has helped to inform future directions for TGH as a digital equity organization. As we’ve already noted, we have seen increased trust and understanding among TGH’s community because of our project. While this can be difficult to measure, these impacts should be considered part of TGH’s evaluation efforts in the future. In addition, TGH is interested in developing plans for focus groups with members of their community, as well as continued community engagement informed by our projects.

The advocacy team at TGH is interested in engaging in more targeted and actionable conversations with state agencies, offices, and legislators. The goal is to more deeply influence digital equity policy in Boston and statewide, including addressing some of the social justice and racial equity issues related to TGH’s work. These include stronger connections between digital equity, academic achievement, economic opportunity, health access, and civic engagement for those most vulnerable in our society.

Our research team also increased our public profile as a direct outcome of a participatory research project. As co-authors of our white paper, we were invited to share the findings from our research on the Connected Nation (2024) podcast where we spoke with host Jessica Denson about the findings included our white paper. In addition, Kang-Le was invited to join a Channel 5 news segment in Boston to discuss the findings from our participatory action research project.

As a result of our researcher-practitioner collaboration, we have already seen commitments from TGH to approach evaluation and/or research differently. This has included doubling down on investments in evaluations by hiring new staff researchers and developing a new learning and evaluation department. Our work on this participatory research project helped validate this strategy and moved TGH in this direction, as a result. In addition, TGH is interested in using our project as part of its long-term planning to position itself as national experts in the field of digital equity research and practice. TGH has additional plans to engage its community through focus groups and finding additional ways that the organization can learn through this process. Lastly, as TGH expands its footprint geographically, the benchmarks developed through this project will be useful in its conversations with other municipalities and states.

Conclusion

In this paper, we sought to address a gap in the digital equity and PAR scholarship by presenting findings from our study to show the value of a researcher-practitioner PAR collaboration to develop a digital equity theory of change. We used Cornish et al.'s “six PAR building blocks” as an analytical framework for describing the participatory research process that was used to develop a digital equity theory of change with Tech Goes Home in Boston, MA, USA. More concretely, we described how we used our PAR project team’s thirty-three-page meeting minutes document which provided the evidence to respond to the list of thirty-five questions from Cornish et al.'s (2023) six “prompts for designing a PAR project” (p. 5). We attempted to show how using this document as a source of evidence from our project provided us with a structured approach to studying, reflecting on, and understanding the value of using PAR to guide our work together. The purpose of this study was to address a gap in the existing scholarship and to more deeply reflect on our collaboration using PAR as a research/practitioner team. As researchers and practitioners working together to advance digital equity, our study found tremendous value in using PAR to create a theory of change, particularly in the context of the current $65 billion investment in universal broadband and digital equity in the United States over the next five years, particularly to ensure that those most impacted by the digital divide are represented in the solutions to the problems identified by the Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act of 2021.