Introduction

Individuals with disabilities, such as those with a spinal cord injury (SCI), should be partners in the development of evidence-based programs aimed at promoting their health and function (Drum et al., 2009). Robotic exoskeleton Gait Training (RGT) may enhance functional outcomes when utilized by individuals with SCI during the acute recovery phase (Tsai et al., 2021) and have been feasibly integrated during inpatient rehabilitation (Swank et al., 2020). Despite promising research (Gomes-Osman et al., 2016), no clinical guidelines exist for the delivery of RGT for people with SCI during inpatient rehabilitation. Our team sought to address this gap by developing a stakeholder-informed RGT program by partnering with individuals with lived SCI experience and then conducting a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) to compare usual care gait training to the RGT intervention (Swank et al., 2022).

An often-cited criticism of using a RCT design is the trade-off between internal validity and external validity (Goodkind et al., 2017; Meldrum, 2000; Rothwell, 2005), which may inadvertently reduce relevancy for the community it aims to benefit without an emphasis on translation and patient-centered outcomes (Israel et al., 2001). Therefore, we aimed to use the guiding principles of a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach (Israel et al., 2001; Viswanathan et al., 2004) within an RCT. True CBPR approaches involve engagement of partners in all phases, mutual benefits of all partners, and entails a long-term commitment by all partners (Israel et al., 2001). This may make CBPR difficult to integrate in settings which have heavy regulatory requirements and rapid turnaround in funding cycles. Additionally, our project sought to examine the efficacy of a pre-existing clinical intervention rather than designing an intervention from the ground-up with community partnership. Therefore, our objective was to describe our community-based research approach within an RCT through utilization of a community advisory board (CAB). Specifically, we describe our processes and lessons learned from both researchers’ and community members’ perspectives to inform similar future research endeavors.

Methods

Stakeholder Engagement

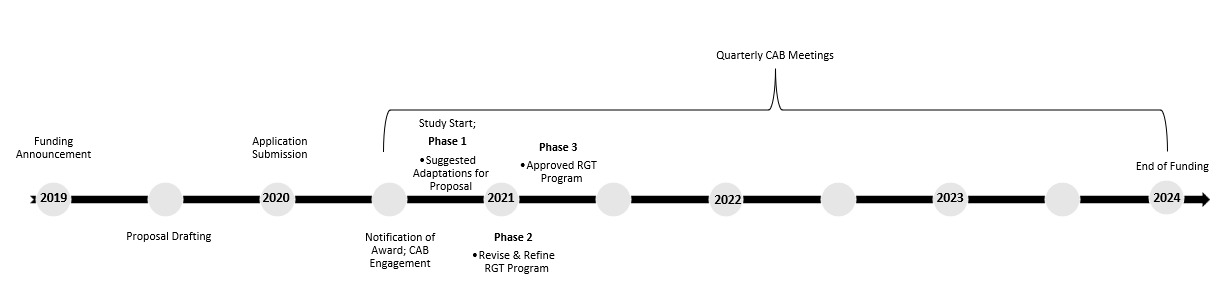

Our community engagement approach began with identifying potential CAB members following the initial funding announcement (see Figure 1 for timeline). CAB members were identified through personal networking of research staff (e.g., prior clinical relationships). Individuals were selected based on professional or personal capacities relative to SCI, experience with robotic exoskeleton technology, and a desire to have a broad range of perspectives represented. We included individuals with lived experience, healthcare providers, and researchers to comprise our CAB. Our choice to utilize a CAB was based on 1) the research objective of informing clinical implementation guidelines, 2) a desire to include patient-reported outcomes in the research aims, and 3) to satisfy funding requirements for community engagement. During conceptualization of the proposal, potential stakeholders were asked to provide input on eligibility criteria, safety considerations, and outcome selection, as well as sign letters of support. Potential CAB members were informed about the likelihood of proposals being funded and provided an estimated notification timeline. Upon receiving news of funding, CAB members were asked to complete letter agreements, which outlined expected contributions, estimated hours, and compensation. All individuals from the original proposal also agreed to participate in the CAB.

The finalized CAB consisted of 9 key stakeholders: 5 individuals with SCI lived experience (3 men and 2 women) with a range of injury level and severity, an SCI Physician, a Rehabilitation Psychologist, an RGT certified Physical Therapist and an RGT industry representative (See Table 1). The study was officially launched in 2020 and Advisory Board members were included in every phase of the study (see Figure 1 for additional details). CAB members were compensated $500 for year 1 and $250 for years 2 -4 based on anticipated time commitments of 8 hours for year 1 and 4 to 6 hours for years 2 and 3. Time was anticipated to comprise of up to four 1 or 2 hour-long meetings annually with additional hours anticipated for review of materials.

Overall Stakeholder Involvement: Communication was primarily through email with two researchers coordinating the CAB, as well as mediating and organizing the meetings. Electronic scheduling polls and draft versions on a shared drive were used to track correspondence. At the request of the CAB, all meetings were conducted via a videoconferencing platform and held in the late afternoon/early evenings to accommodate working hours and external commitments. Routine communication included coordinating agreement forms/payment paperwork at the start of each calendar year and scheduling 4 to 6 weeks prior to expected meeting times. Attendance was recorded and follow-up emails and collated notes were emailed following each meeting. The following framework was utilized during the project period to outline CAB involvement:

Phase 1

Phase 1 involved engaging the CAB to collaboratively develop content (e.g., dose considerations of intensity, feasible progression schedule) and structure (e.g., clinical factors to initiate RGT, transition to mobility needs at discharge) of the RGT program prior to study initiation. The inaugural meeting at the start of 2021 involved a 3-hour virtual meeting about study-related procedures and key focus areas of RGT program development. As with other meetings, the meeting was recorded and primary take-aways were transcribed by research staff. These notes were emailed to all CAB members along with solicitation for additional feedback.

Phase 2

Phase 2 involved refining the program and study measures through an iterative process. This entailed review of study materials, including questionnaires, procedures, and recruitment materials, prior to meetings and open discussion and note-taking. Following meetings, additional feedback was solicited and agreed upon changes were implemented and presented prior to submission for regulatory approval.

Phase 3

Once the program was finalized, data collection began in 2021 and CAB members attended quarterly meetings for the entire funding period. Phase 3 entailed two subparts: 1) launch of the approved RGT program/ data collection and 2) review of outcomes and the final program at study conclusion. Meetings during this phased focused on updates about progress, enrollment, recruitment, and adverse events. At the conclusion of enrollment, program and study outcomes were summarized by research staff and formally presented to the CAB. The CAB collaborated on dissemination efforts, including manuscripts and fact sheets developed both for clinicians and individuals with SCI. CAB members were also involved in subsequent research efforts to maintain community involvement and partnerships across multiple funding lines.

Lived Experience Consultant (LEC) Survey: Following the formal award period, CAB members with lived experience were asked to participate in a brief survey. Questions were developed by the research team based on prior literature to inform process improvement. Survey items were:

-

Do you perceive your time was valued while participating in the FIRST advisory board? Can you provide an example of how you believe your skills or expertise influenced the study?

-

Do you believe you were compensated fairly for the time you committed? Why or why not?

-

Do you have suggestions for how we might change the role of the advisory board for future research? Please include suggestions on how to communicate about meetings, platforms, or frequencies for meetings, how to best gather input from advisory board members, or things you liked or didn’t like about your involvement. Please provide specific examples.

-

Anything else you would like to share about your experience on the advisory board for the FIRST study?

Results

Initially, nine individuals formally agreed to comprise the CAB; there was turnover with one CAB member in the first quarter, so an additional Rehabilitation Psychologist was brought in and remained throughout the remainder of the study. Overall retention of CAB members was excellent across the four years with 100% of CAB members remaining involved even if unable to attend every meeting. Recorded attendance averaged 70% for all 9 CAB members, however even if members were unable to attend scheduled meetings, communication and engagement remained high with each CAB member via emails.

From the perspective of the research team, CAB members were essential in informing study aims and ensuring milestones and deliverables. Specifically, several protocol changes were made to the RCT as a direct result of CAB involvement. These changes were to 1) expand inclusion criteria from ages 18 to 70 years to ages 16 to 70 years, 2) include concomitant mild/uncomplicated traumatic brain injury, 3) provide opportunities for patients to engage with the clinical team regarding pros/cons to participating in RGT, 4) reach 90 minutes/week of RGT, but allow for individual flexibility determined by patient tolerance and therapeutic priorities, 5) assess affective outcomes (e.g., depression, anxiety) in addition to gait and mobility performance, and 6) include open-ended questions on patient surveys. Additionally, across all non-standardized survey items Advisory Board members helped convert language to be more “person friendly” such as changing a question from “Please describe observable changes” to “Did you benefit or not benefit?” to enhance survey flow and reduce testing fatigue. Furthermore, CAB members were helpful in identifying solutions to meet enrollment goals, such as suggesting that medical staff (versus research staff) provide details about how study procedures might compare to usual care or offering outpatient RGT sessions to incentivize retention for those not assigned to the intervention group.

LEC Survey Results & Perspectives

A total of 4 out of 5 LEC responded to the survey. Results were reviewed by the primary CAB organizer and summarized for brevity with exemplary quotes. All LEC members of the CAB perceived their time as being valuable and provided overall positive feedback about their experience. Members referenced the value of their lived experience and the potential impact it has on helping other individuals with SCI. One responder perceived their involvement as “ensuring that the research methods do not detract from the VITAL “usual” PT care that focuses on functional activities required for patients to return home safely despite shorter lengths of stay compared to past lengths of stay.” One individual explained that their experience with RGT was particularly valuable, stating “using my exoskeleton device since 2015 has allowed me the opportunity to stand and walk which is tremendously valuable to my overall health and well-being and would not be possible without the use of this technology.” Another response exemplifies the importance of having LEC to ensure that research efforts do not detract from overall healthcare goals; “I worried that taking the time to use these devices might take away from other vital training the patients required to maximize functional abilities. However, the therapists and researchers on the team did a great job to ensure that participation in the study would not be detrimental to patients’ overall rehabilitation success.”

When asked about compensation, 3 of 4 responders agreed it was fair, timely, and unexpected based on prior experience. The 4th responder explained “as a working professional in this industry, I often believe [individuals with] lived experience [are] underpaid for their high-level knowledge and their important insight brought to the study. I do hope as research develops budgeted amounts increase for the expertise of lived experience.”

Overall feedback about the member experience in the project identified several strengths, including comments that the CAB was well-handled, organized, efficient, and that they appreciated the clear communication and frequency of meetings. One person said that “the meetings were well structured and organized to minimize discussions veering off task with prioritized agenda items succinctly yet thoroughly discussed. The meeting coordinators did a nice job to ensure all voices were heard and they frequently expressed appreciation for all contributions. The researchers also gave the advisory board members choices via doodle polls to select convenient times and did a good job to ensure meetings started and ended on time out of respect for everyone’s busy schedules.” Specific suggestions for improvements included: 1) using a different video-conferencing platform, 2) embedding LEC into participant recruitment efforts to leverage a “chair-to-chair” approach, and 3) holding one of the CAB meetings in-person for more informal interactions.

Additional feedback generally described the value of including individuals with lived experience, such as “they have been open to our lived experience feedback during this study. Working in the SCI community and exoskeleton industry for almost 10 years, it is wonderful to see federal research grants requiring and integrating people with lived experience. The funding agency for this project as well as the research team value the insights these individuals bring with SCI lived experience.” Another member echoed this sentiment, stating “by including Advisory Board members with lived experience, the patient voice was captured throughout this study and this engagement helped foster a sense of trust between the researchers and the patient community. I consider it an honor to have been involved in this project alongside researchers, clinicians, physiatrists, and other lived experience Advisory Board members. Together, we brought decades of experience to meet the needs of the patient and provide the educational research needed to advance the exoskeleton industry. As I often say, "It takes a village and a voice!”.

Conclusion

We aimed to describe the utilization of a CAB within an RCT from the proposal stage through study execution. Engagement of stakeholders across the life of the project enhanced the robustness and generalizability of trial outcomes as well as recruitment and retention efforts. t. Based on researcher, CAB, and LEC feedback we believe our approach successfully balanced rigorous study design with community involvement that may be more feasible than a true CBPR approach. Future research should consider adopting similar CAB approaches, as well as increasing compensation, balancing virtual and in-person meetings, and further involvement of those with LEC within the project (e.g. recruitment efforts).

Funding Disclosure

The contents of this manuscript were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90IRFE0043). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this abstract do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Acknowledgments

We are tremendously grateful for the contributions of our advisory board members Jorge Martinez, Bill Bergeron, Elizabeth Daane, Christi Stevens, Dr. Ann Marie Warren, Dr. Rita Hamilton, and Michael Glover for their steady engagement and insightful contributions over many years.