Introduction

This article describes the evolution of an idea formulated over several years by the COMENSUS group, a service user and carer involvement initiative at a north-west UK University. The group was created through a participatory action research project to help embed the voices of those with lived experience of health and social care services into professional education. The group currently consists of over 100 people from the local community with different experiences and knowledge. Social care is defined in the UK as the wider support and personal care which is provided to adults and young people ‘with physical disabilities, learning disabilities or physical and mental illnesses’. (King’s Fund, 2017). Our university offers professional health and social care courses governed by UK professional bodies such as the Nursing and Midwifery Council, Social Work England, and the Health and Care Professions Council, who all stipulate that service users and carers must be involved in the programme. This work is often described in the literature and healthcare field as ‘service user and carer involvement’ or more recently, ‘patient and public’ or ‘citizen’ involvement and is a way of enhancing domains of professional practice, education, or research with authentic personal experience. In this regard, it is acknowledged that service users and carers can be disempowered in their relations with health and social care services, universities or policymakers, and the participatory process by which effective involvement can be supported are a means to remediate these power imbalances (Felton & Stickley, 2004). Democratised approaches to supporting such involvement resonate with practices associated with coproduction (Raffay et al., 2022), and similarly must surmount institutional impediments (Lewis, 2014) and resist forces of co-option and incorporation (Eriksson, 2018).

For many years, the Comensus service user and carer involvement group have raised concerns about their own lack of power and lack of information as ‘outsiders’ at the university (McKeown et al., 2011). Funding streams are increasingly under threat in the current financial climate. Ocloo et al. (2021)’s review of papers up to 2018 also highlighted finance as a major issue for service users and carers. Decisions about the management of patient and public involvement or engagement are often taken without consultation or discussion with those actively engaging in this area of work. Moreover, service users and carers wish to know that what they do has value and creates impact. Increasingly cost-conscious universities typically pose questions around value for money, and established initiatives like Comensus have become familiar with having to justify their worth to the wider organisation. Interestingly, a key driver of our research question and the rationale for this research project was the service user and carer group’s own wish to address these issues and co-create a measure of impact which would provide ‘hard’ evidence of their contribution to professional education.

Early reviews of service user and carer involvement in education and practice recommended further research in this area, and ongoing evaluation of student learning, if patient or service user involvement is to be funded and supported in the future (Jha et al., 2009; Terry, 2012). Whilst we have seen a welcome shift towards acceptance of the patient and community voice within education, further evidence is always necessary to promote and support involvement and ensure it becomes fully accepted and embedded in the culture of organisations. A key concern of ours is that authentic and direct user involvement in education may not be sustainable when resources are restricted, student numbers are increasing, and educators are not fully committed to partnership working.

Participatory action research methodology

Given prevailing concerns around power relations, we chose a participatory action research approach to ensure effective participation within our project and tackle any existing power imbalances head on. The university had in the past often struggled to engage with the community and continues to work on their relationships. We believed therefore that involving a group of peer researchers from our community would add value to this project as well as the university’s wider public engagement agenda. We also wished to embed empowered participation within a more broadly cast mixed methods approach to inquiry. PAR research is a methodology centred in collaborative practice where the researcher or researchers invite marginalised community representatives to work alongside them as equal partners, in order to address a local issue and create social change (Kemmis & McTaggart, 2007). A democratic, collective approach is adopted by actively seeking to include those who have been excluded (Mertens, 2008). Participants and stakeholders on the ‘outside’ are invited ‘inside’ to help create change or improve their own area of practice. Our stakeholders in this instance included students enrolled on pre-registration nursing programmes at our university, academic partners who were managers and lecturers and most importantly, members of our local community who regularly shared their lived experience with students. In this instance, we view our community members as the ‘marginalised’ as they are often dismissed as secondary participants in academia and pre-conceptions about their level of education can be a barrier to inclusion. They often also mention a lack of confidence in their ability to contribute to academic research due to missing post-16 education and other issues.

When approaching research through a transformative lens (Mertens, 2021), there are several guiding principles; namely, that the research question or ‘problem’ should come from the community, community members should be invited to collaborate as co-researchers, diversity and power dynamics should remain at the forefront of people’s minds throughout, ethical concerns should be reflected through reflexivity and positionality, and the research should benefit the community concerned and facilitate social change (Mertens, 2008, 2021; Ozano et al., 2020). This commitment to progressive social change makes the practice of PAR congruent with and underpinning critical social theory of human relations (Boog, 2003).

In this study, the use of mixed methods under an overarching PAR umbrella helped to facilitate the inclusion and empowerment of people with different skills-sets, abilities and experience (Mertens, 2008, 2021). The use of mixed methods also arguably adds strength to the validity of the research outcomes; combining qualitative and quantitative data can enrich our understanding of a research question, enhance the robustness and validity of the findings, address the limitations of a singular approach and mitigate arguments of bias in the data collection process (Creswell, 2009; Greene, 2007). Taking a reflexive approach with the participatory group also invites open and deliberative discussion of any issues or key points and can also help to encourage direct democratic dialogue between researchers.

A key element of PAR research is the power to ‘disrupt’ traditional knowledge and accepted practice, and barriers within organisations and existing mindsets can prevent this (Cook et al., 2019). A ‘dialogue model’ approach to PAR research created in the Netherlands (Abma, 2019) advocates for collaborative working from the outset, between stakeholders such as patients, families, academics, and health professionals who may not have met each other previously. For democratisation of knowledge to occur, dialogue and disagreement must move towards shared understanding and appreciation of another’s view (Cook et al., 2019, p. 15). Hence, the value of the external or outsider perspective (researchers) to transform this ‘insider’ perspective and challenge the status quo. The Comensus group at our university have regular dialogue and discussion with their academic colleagues to facilitate joint-working.

A note about terminology

The Comensus group of community members have historically used the terms ‘service user’, ‘patient’ and ‘carer’ in their work and publications (Downe et al., 2007; McKeown et al., 2011). However, as public involvement has become more accepted in healthcare education and services, we recognise the recent shift in language, to include ‘people with lived experience,’ expert by experience, public involvement members, patients, consumers, and clients. We appreciate that other groups and individuals will prefer different terms. In addition, community researchers may be named as peer researchers, co-researchers, or participant researchers in this field of work.

Embarking on the ethical challenges relating to PAR research

Many of our wider service user and carer involvement group members are motivated to make a difference to future service provision. On commencing this project, the doctoral student recruited a smaller group of people to be co-researchers and presented the study to the Ethics committee as equals exploring and learning together. However, it is important to acknowledge the potential to ‘romanticise’ this approach (Roura, 2021) and not pay heed to the disillusionment, disappointment and frustration that can occur when adopting participatory methodologies.

In the article ‘‘You Get a PhD and we get a few hundred bucks’: Mutual Benefits in Participatory Action Research’', Jennifer Felner (2020) points out that many idealistic doctoral students conducting participatory research fail ‘to prepare for the practicalities and challenges of such research’ (Felner, 2020, p. 549). The lead author of this paper and former doctoral student was confronted by many challenges. Felner’s project, which involved participants from a local youth group in the US, describes how participant researchers challenged the notion of equality in decision-making during the project; some disengaged and others questioned what they themselves would ‘get out’ of the project. Felner later considered the restrictions imposed by university ethics committees and wished she had spent more time ‘creating space for [the participatory research group] to share, listen and co-examine how all the partners might benefit from participation’ (Felner, 2020, p. 554). On setting out on our own research journey, we agreed this was an important consideration for our group, as we progressed through the separate phases of the project, especially as these occurred during unprecedented periods of enforced societal lockdown and we had limited face-to face time together.

Ethical approval was sought from the University Ethics Committee in two separate applications; firstly, in June 2020 prior to the scoping review and qualitative phase, and secondly, in July 2021 prior to the development and testing of a new impact measure. Concerns were initially raised by our university’s Ethics Committee regarding the vulnerability of service users and carers participating in this process, as well as the short- and long-term impact on their mental and physical health. We successfully argued that, as the research was based on a participatory-transformative approach (Mertens, 2008) which advocated for the upskilling and inclusion of the community in research, it was imperative that they were included. Assumptions could not be made in advance about the participants’ short- and long-term health, and yet the Ethics committee would have liked to know this information in advance, possibly due to a lack of understanding about the participatory group. Care was subsequently taken in all the information sheets and consent forms created and distributed to participants to differentiate between participants and co-researchers, and to explain to the co-researchers that they would be free to withdraw at any stage if they became unwell, without any detriment to their subsequent involvement with the group (see appendix 2 for further details). We stated that we would each monitor everyone’s health and wellbeing throughout and signpost to other agencies if necessary. We were keen to experience the highs and lows of conducting research as equals.

A second concern raised by the university’s Ethics Committee further highlighted the confusion and lack of understanding at the time about participant researchers. This query concerned the issue of maintaining confidentiality for all participants. Traditionally the privacy and confidentiality of all participants’ data is paramount; however participant researchers may choose to be named and credited in any future publications or presentations about their work.

During this participatory study, participant researchers were invited to share their reflections, regarding their development and progress. It is the nature of PAR for reflexivity data to be considered legitimate data and this was made clear to PARITY researchers from the start. Reflections were collected throughout the thesis stage and each co-researcher took a different approach. Some of us kept a journal, others were happy to wait and respond during our regular online meetings. It was always our intention to include some of these reflections in any dissemination of the work (including the doctoral thesis) to help elucidate some of the challenges and benefits we faced as part of the participatory process.

Ethics statement

This study was approved in two stages, in 2020 and 2021 by the BAHSS Ethics committee of the University of Central Lancashire reference number BAHSS 0104.

Setting up the PARITY group

Our university service user and carer group consists of over 100 volunteer members, who have substantial experience of collaborating with academic partners to educate future health professionals and co-design healthcare curricula at our university. Issues of democracy, power and social justice are frequently discussed within our meetings and are also key to the methodology we chose for this project.

Service users and carers from this wider group who had ongoing engagement with the School of Nursing were invited to be involved in the research study. It was the doctoral student’s responsibility to submit all requests and revisions to the University ethics committee. The criteria for selection to the research group were:

-

Substantial involvement in nurse education within Higher Education

-

Experience or interest in engaging with research.

-

Interested in the topic of measuring impact

-

Prior knowledge of conducting research

-

Committed to developing personal skills and knowledge

Six people from the wider involvement group offered to help with this first stage (see further details in Table 1 below); they declared that they were interested in the topic, had knowledge to share about the impact they had personally witnessed, wished to support the doctoral student in their personal development and develop their own skills and knowledge.

We hoped to harness their intersectional diversity to include their different skills, perspectives and approaches to the research question, to involve everyone as co-researchers in all four stages of the study and as co-authors of any dissemination activity at the end of the project.

Whilst some already had substantial education, qualifications and experience, which were of significant value for the group; in consideration of the democratic and relational qualities necessary to the participatory dynamic, other experiential qualities such as mentoring, encouragement of others and interviewing skills were deemed by all to be of equal importance. Most people had experience of being invited to participate in research previously but not conducting the research. The researchers had often been invited to participate in focus groups but lacked experience of conducting interviews and analysing qualitative data. The two postgraduates in science subjects did have some experience with handling quantitative data, coding, information software and measuring questionnaires; these members assisted with the final stage of survey design and quantitative data analysis. Conversely, others in the group had a vast amount of experience in talking to students, through their involvement in recruitment, teaching and assessment, and these members were keen to be involved in helping to design the interview schedule and conduct the interviews.

We used a polling tool on Microsoft Teams to share ideas for names and vote for our favourites. At an in-person meeting we discussed the relative merits of each choice and finally decided on the name ‘PARITY.’ We hoped this name would capture the democratic/egalitarian principles of the group woven around the acronym for participatory action research.

Questioning what we mean by impact

There is a wealth of research which highlights the need for experts by experience to justify their value to the academic and other professional bodies (Happell et al., 2021; Hughes, 2019; Staniszewska et al., 2011).

‘Are we seen as ‘less’ value than others? We have qualitative feedback from our stakeholders that service user and carer involvement at our university provides value to the students, to service users and carers and everybody who is involved with the group. How do we know? We are constantly receiving positive feedback and have been since the group was formed. Yet something about what we do has led to a constant need to feel valued. Is this because of financial or other more subversive ideas planted in society to point out that volunteers are a drain on society?’

(PARITY member F)

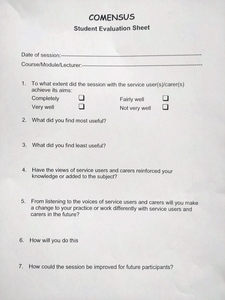

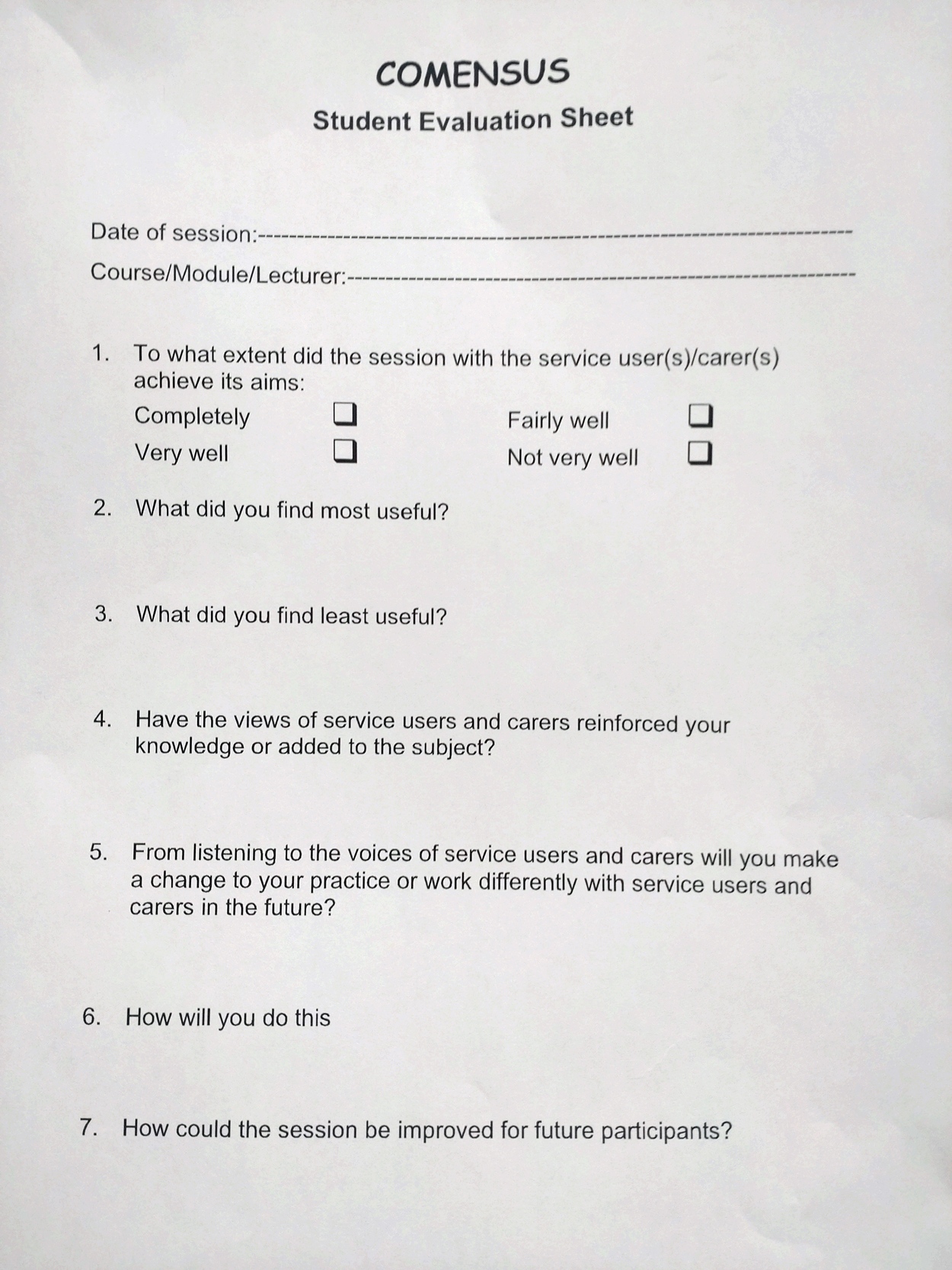

Conscious of this continuing need to provide feedback to senior managers of the value of service user and carer involvement (Happell et al., 2021), a co-designed evaluation form had been in use for several years which was used to gather feedback from academics, service users and students in receipt of service user and carer presentations (McKeown et al., 2011, and appendix 1). However, the newly formed PARITY group wished to go further and develop a more structured, robust measure using established research methodology, to explore the value added using participatory methods during each stage of the study:

-

What is the impact of service user and carer involvement on student nurses at our university?

-

How have other academic researchers sought to evaluate the impact of service user and carer involvement in professional health and social care education?

-

What do government bodies or other organisations say about measuring impact?

-

Can we co-create an impact tool together that is based on what service users, carers, students, and academics think we should be measuring as part of future nurse professional development?

Using a variety of participatory research methods

Mixing methods to facilitate inclusivity

This study aimed to address the perceived lack of quantitative measurable evidence of the positive impact of service user and carer involvement in professional education. We were mindful that a purely positivist approach to designing an impact tool could risk reducing or minimising the personal and authentic contributions that service users and carers have made to the professional programmes over the past years and downgrade these in some way to plain numerical data and statistical analysis. By adopting a mixed methods approach, we chose an approach commonly used in health care research to combine quantitative and demographic data with the lived experience of professionals and patients/service users to evaluate care, and one that aligns with our desire to include those who feel marginalised or excluded from academic research (Mertens, 2021). Mertens advocates for increasing the value and impact of such research by agreeing ‘a thoughtful design and inclusion of stakeholders and formation of coalitions that can sustain the needed change’ (Mertens, 2021, p. 2).

PARITY chose a sequential exploratory design (Creswell, 2009; Jackson et al., 2018):

-

Stage 1- a scoping review of published and ‘grey’, unpublished literature conducted by PARITY members F and G working together.

-

Stage 2- The whole group were then involved with exploring the lived experience of key stakeholders in the curriculum creation process (student nurses from different fields and cohorts, lecturers, managers and service user and carer participants) to gather and agree codes or themes. This constructivist or interpretivist approach focuses on how individuals interact in their social world and make sense of their own reality (Robson, 2011, p. 25). Whilst the researcher is an individual, they are also part of a society; they are therefore part of creating their own reality just like the millions of other individuals who inhabit our planet:

‘Ontologically speaking, there are multiple realities of multiple truths based on one’s [own] construction of reality’ (Sale et al., 2002, p. 45). Their own perspective or influence must be acknowledged and included in the results.

-

Stage 3 and 4 adopted a positivist approach in the development and psychometric testing of a co-designed measure of impact. We will describe these latter stages in a companion paper, which will document the systematic approach to developing and refining the impact measure together.

Participatory remote methods

The Covid-19 pandemic of 2020-21 caused global disruption to our personal and working routines. It forced university staff and students to work from home from March 2020 and utilise remote means (specifically, Microsoft Teams) to conduct all teaching, meetings, and other communication. This shift to remote digital working arrived just as we were preparing to embark on our field work. The immediate challenge was to ensure participant researchers had access to the appropriate equipment, technology and Wi-fi to be able to conduct their research from home. Several months were spent setting up University accounts, arranging the loan of equipment and training people remotely on how to use Microsoft office so that they could continue to make a meaningful contribution to teaching and learning, and also participate in essential strategic meetings such as course approval visits from our Professional bodies (NMC (Nursing and Midwifery Council) (Nursing and Midwifery Council), HCPC (Health and Care Professions Council), etc.) and feedback meetings.

In some ways, this experience helped us all approach the organisation and planning for conducting research remotely more calmly and pragmatically than other colleagues at our institution. We attended meetings during this period where the ethics of interviewing online were discussed, including the extra precautions which may be required such as extra person to help with the observation of body language, and handling any technical issues. Fortunately, a sizeable proportion of the PARITY group had existing IT skills or were being supported to continue with their involvement remotely. By this stage, members were delivering presentations online, interviewing prospective students and engaging in teaching sessions several times a week, so being asked to participate in this first stage of my research from home was not so daunting as it may have been in ‘normal’ pre-Covid-19 times. All the group commented that taking part in this research project and other activities helped to combat feelings of loneliness and isolation during the period of mandated restrictions, particularly those that lived alone.

Stage 1 - Reviewing the literature together

An initial ‘scoping’ review of the literature was conducted by PARITY members F and G to determine how other researchers and practitioners were seeking to measure the impact of service user and carer involvement in education. Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework was used to help with this. A scoping review can help to clarify a working definition in an emerging field (Tricco et al., 2016) and can be particularly useful in the field of social science where a range of methodologies are often employed.

PARITY member F had recent experience of conducting literature reviews for his Masters’ degree, and regular online meetings were held to consider the research strategy, review selections and finally to agree a summary of the findings. This article does not describe the findings of the review in detail; however, it is important to state that 78 articles were included in the final selection for thematic discussion. Both PARITY researchers found this stage very tiring and challenging in many respects. The impact of the pandemic was already exacerbating pre-existing mental health issues, so often the review felt overwhelming and hard to manage.

'I found this first meeting very hard after the first hour. We got things done but I felt guilty. I’d only looked at around 8 papers. I wanted to do more but didn’t feel motivated.’

(PARITY member F).

Stage 2 - preparing for qualitative enquiry

PARITY group came together in the summer of 2020 for our first meeting and to reflect on our previous experiences of research, of our motivations for embarking on this project and of the potentially different relationships we could expect to have as co-researchers instead of as involvement co-ordinator and volunteer. The doctoral student led this first meeting and reflected:

‘I was surprised by my nervousness ahead of this first meeting, though I later reflected that was due to a shift in roles and a potential shift in power relations. Would I be expected still to lead and have all the answers to their questions? Would they expect me to be an expert and knowledgeable already in the research process when I was still learning? Might there be conflicting ideas of how the research question should be addressed or even suggest an alternative research question at this stage? Of course, there was no need to worry as the group were very relaxed and willing to support me in developing myself as a researcher. They had already suggested the research question in earlier discussions; they had witnessed my personal and professional development and supported me as a facilitator; they would continue to support me as a research student, and they were happy that I was continuing to demonstrate authentic values by including them as co-researchers. The long-term nature of our relationship meant we felt at ease with each other and were not afraid to speak openly and honestly about our feelings and reservations about the project’.

(PARITY member G)

Our schedule of meetings and workshops is depicted in Table 2 below.

We also felt it was important to capture the different motivations of the group. Those who already had postgraduate experience and knowledge were very keen to engage in research activity again; the rest were eager to learn new skills and learn more about the subject area as they hoped this would enhance their understanding of how their involvement helped develop future nurses. They were also excited to explore different perspectives regarding service user and carer involvement from students and academic staff. PARITY member F had already been helping with the scoping review so he expressed a desire not to get too much involved with the interviewing so that he could focus his attentions on that part. Most importantly, it was essential to establish that the process was intended to be equitable for the group, whilst being mindful of their health conditions and caring responsibilities potentially impacting on their time for the project (see Felner, 2020). From their previous experiences, the group felt confident this would happen, so they felt relaxed and happy to commit some of their time to develop new skills and collectively develop some solutions to this research question. All participants were informed that they could withdraw at any time should they feel this was not suitable or enjoyable for them, but the reality was that the group cohered, and membership was sustained to conclusion of the project.

Participatory Workshop 1 – open online discussion (Stage 2)

As a collective, we discussed who we would like to interview to seek out these different perspectives. Suggestions included practice partners, mentors from practice, patient liaison workers, service users and carers from Comensus as well as students and staff from the different fields of Nursing: Adult, Mental health, Children and Young Peoples and Return to Practice Nursing. The limitations of this project meant we could only interview those involved with pre-registration nursing courses within our university setting.

We considered the differences between structured and semi-structured interviewing, and then the role of the objective interviewer and the types of questions that we might hope to ask and in what order. We discussed the difference between inductive and deductive approaches and agreed to adopt an inductive approach during this stage to eliminate any concerns regarding our pre-existing knowledge, by being aware of consistency amongst the interviewers and carefully structuring our questions. There were concerns from some group members that we might let our guard down and impose our own feelings or opinions on the interviewee; the group were keen to overtly convey to the participants that we would be looking for honest responses, and that we would not be upset by any negative feedback or opinions that did not correspond with our own. The group were also eager to express that they wanted to ‘do things properly’ and be professional in their approach by discussing the need for confidentiality and the importance of adhering to data protection guidance. PARITY was also required to complete online Information Security training before commencing this stage of the research and reminded of the need to keep people’s identities confidential throughout. Some examples of the questions included:

-

What do you understand by service user and carer involvement in the pre-registration nursing courses?

-

Can you tell me about any service user and carer involvement in your course or module?

(Explore first impressions and any anxieties or assumptions the students or staff may have had).

-

What do you think future nurses and staff can learn from service users and carers?

-

Do you think that key skills or attributes learnt from service users and carers are something that we could measure? How could they be measured?

Following the initial meeting, we convened two optional practice interviewing sessions and practiced interviewing in triads with our co-designed questions. One of us asked the proposed questions, another was the interviewee, whilst the third person observed and gave feedback to the trainee interviewer. All the group found this particularly helpful and one commented:

'In the initial meeting I did struggle at first, as this was all new to me, the way the research process works and now I feel confident…’

(PARITY member C)

During our online meetings in September 2021, we were also able to collectively refine and update our interview schedule questions. The group suggested creating three different schedules and amending the language to be appropriate to the separate groups of people we wished to interview: Staff, students, and service users.

A collaborative workspace for all participants was created on Microsoft Teams at the request of the PARITY group, which enabled us to communicate with each other using our university email accounts. By adding each member to the Team and uploading the necessary documents, members could keep abreast of updated information, meeting dates and invites and supporting paperwork including the information sheets that had been sent out to potential research participants, consent forms, ethics guidance and so on. This avoided a build-up of unnecessary emails and updates for PARITY group members.

Practice Interviewing sessions - Stage 2

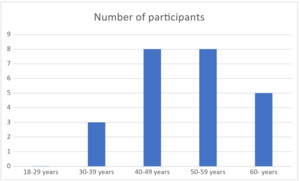

A purposive sample of 24 participants was recruited for this stage (see Figure 1 above). We recruited a variety of stakeholders from Mental Health Nursing, Adult Nursing, and Children’s Nursing to ensure we had representation from each pre-registration Nursing field to help answer our research questions. Course leaders from the BSc and MSc pre-registration nursing degree programmes were involved as well as Module leaders from the Nursing Associate programme. Two managers from the School of Nursing were also happy to be involved. Service users and carers with direct experience of involvement in recruitment, assessment, curriculum design and delivery of teaching were recruited.

We tried to ensure the sample had variation within it. Eight participants were men, 16 were women. All participants identified as White British ethnicity, apart from one female student of Nigerian heritage. A range of age groups was recruited for the sample as below; significantly no participants in the age range 18-30 came forward to be interviewed at this stage.

Participatory Workshop 2 – online, April 2021 (Stage 2)

This workshop was convened to agree our approach to qualitative data analysis. This meeting would review the first stage of our field work then move to the second stage-namely, making sense of the various narratives, words, sentences, repeated phrases, and longer sections of text that we had gathered from multiple interviews. At this second workshop, our aims were to discuss the following:

-

A review of the aims of the research project as a whole

-

Talk about - What is qualitative data?

-

What is the process (or processes) by which we analyse qualitative data?

-

The difference between inductive and deductive analysis

-

The strengths and limitations of the above

-

The coding process: creating broad over-arching themes and sub-themes.

-

Using framework analysis as a participatory tool.

The group engaged with this stage with their usual enthusiasm and verve. We discussed the best method for analysing copious accounts of interview and focus group data in the form of transcripts.

Some preferred to work in pairs for support, but agreed they would read and re-read the transcripts separately and add their own codes or memos to the transcripts first, before then discussing their findings and agreeing these together. This would enable them to use their own experience and skills and learn from their partners. We had agreed that we would inductively code the data and see what emerged; this would require a conscious decision to set aside any personal bias or pre-conceptions regarding any findings.

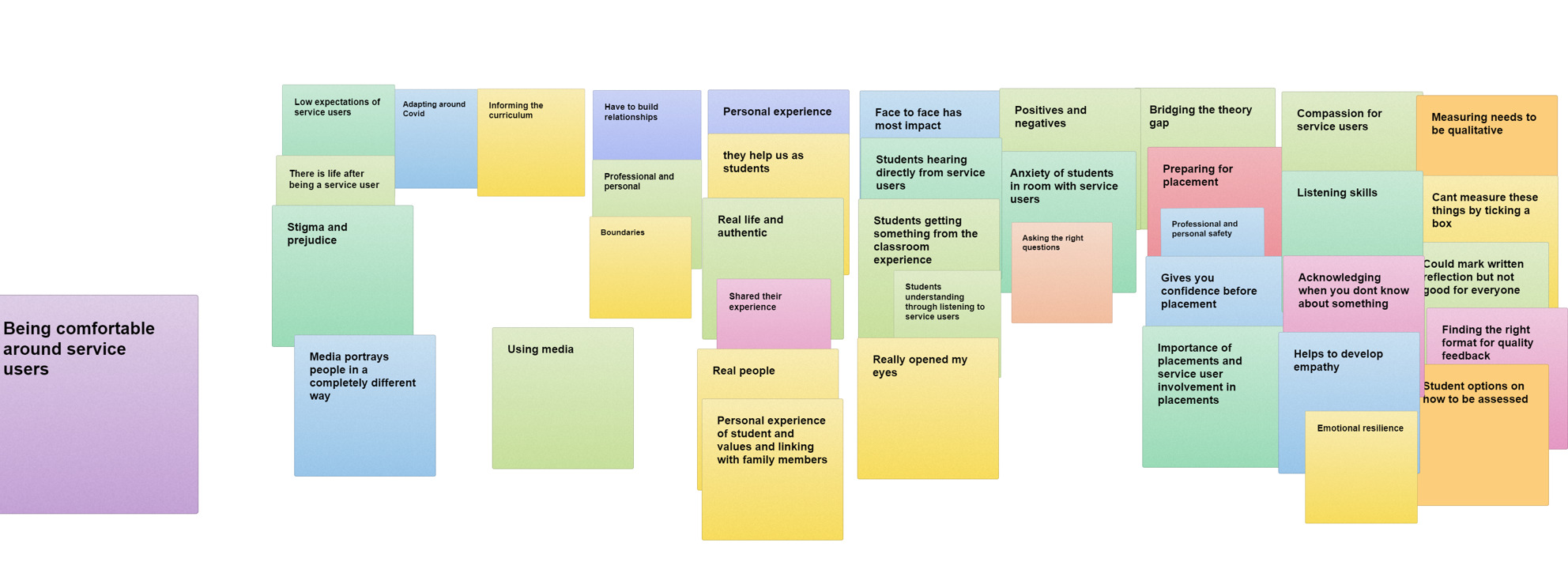

Following a process of reading, re-reading then coding and theming the data, we held a short series of meetings online to talk about our findings and agree the themes.

‘We were all disappointed that we could not meet in person for this stage of the process as it was now summer, and we had worked in isolation for over a year by this stage. However, it was encouraging and even surprising to find the group continued to be motivated and commented that this work was keeping them going through a difficult period.’

(PARITY member G)

In attempts to recreate an in-person participatory group approach to theming our results collaboratively, we sought advice from colleagues and used, firstly, Microsoft Whiteboard to help us visualise the results, then organised these into a table for easy reference (see figures 3 and 4):

Our final meeting of this phase involved charting the themes into a framework using Microsoft Excel software, so that we had a visual template for all participant researchers to view and insert exemplar text from the transcripts they were working on.

PARITY member D reflected:

‘I’ve done a bit of research before, but every project is different isn’t it? You know -what people want out of you, and this was quite in depth, really. … Once you got over the initial, what is this? I quite enjoyed it and the coding because I’ve never done anything like that before. I’m thinking what what’s the idea behind it? And then it clicks……and it was great to be involved from beginning to end.’

‘The coding process on the spreadsheet was quite tricky, I added more than the 3 comments in each interview as I deemed, they were all relevant, However, I did not check with the lead researcher first that this was ok. In hindsight I would have consulted her first and the rest of group.’

And another:

'The coding process of the materials is a feature of the research that was fun as well as reflecting on the subject. We decided on the codes on common understanding.’

(PARITY member B)

Most of the group enjoyed learning how to accomplish aspects of qualitative data analysis such as coding but we all recognised that this stage would have been much easier in person.

Stages 3 and 4 -November 2021 to present

The latter stages of the study provided new challenges for the PARITY group, during which we went on to create a first draft impact measure using the themes from stage 2, followed by psychometric testing. We were aware of recent academic debates commenting on the need to prioritise more robust evidence of the impact of patient and public involvement in healthcare education (Staniszewska et al., 2011) and were eager to embrace a new challenge. Our efforts and commitment to co-create a new measure of impact encouraged the group to embrace new methodologies to complete the project. We believe that this study will go some way to addressing the call for a systematic, theory-driven, measure of impact, which has included co-production methods in all stages of the study.

We will describe the latter stages in a companion paper, which will document the systematic approach to developing and refining the impact measure together.

Lessons learned from adopting a participatory research approach

The following section outlines the group’s reflections on using a participatory approach for this study, and on using the various participatory research methods used to complete it. PARITY researchers shared their reflections throughout the different stages, including the postdoctoral stage. The doctoral student kept her own reflective journal and other reflections were collected during meetings or submitted at their own convenience by email. PARITY have organised these reflections into three key themes.

Increasing confidence

'It was heartening to see the development and increase in confidence on the other researchers as time went on. Some were understandably nervous about their early attempts at interviewing, and it was important at this stage that the other researchers felt supported’.

(PARITY member G)

'On reflection I knew that during the first interview my old insecurities were making themselves known; even though I was the note taker I felt that X’s notes would somehow be more competent than mine and that I might miss something?? I was happy that I was able to maintain my concentration throughout. I welcomed a break before writing up my notes as I find I always need time to assimilate things. X was supportive and inclusive as ever throughout.’

(PARITY member C)

'I felt excited to be involved as there was some interesting points being raised with good suggestions towards a tool to measure the impact of service user and carer involvement. I felt a real sense of belonging to the project yet glad that I wasn’t responsible in having to write it all up as I knew that I would be overwhelmed. I admired their commitment and stamina to tackle such a complex task.’

(PARITY member C)

This person draws attention to the challenge of balancing her own aspirations to becoming a researcher/interviewer with being mindful of the role of the doctoral researcher in leading the project.

'In contrast to the first interview when it came to the 3rd and 4th interview, I was in that place where you feel excited as well as nervous at the same time, it felt like they trusted me today to take the lead in 2 interviews with staff members. Again, I didn’t want to let X down. I was mindful though that this is X’s research project so I need to be inclusive asking them if they would like to ask any questions and close the interview off. It’s helpful too to have a chat with X afterwards to share my feelings about the interviews’.

(PARITY member C)

Another participant researcher found that being involved in a new research venture was rewarding:

'Being involved …was by no means like preparing for an examination working under pressure and demanding of memory and concentration, as these are some of the issues, I have due to my health conditions. We always had ample time to carry on with our day-to-day responsibilities whilst engaged with the project’.

(PARITY researcher B)

‘From previous experience in my degrees I would say data collection and transcribing is exhausting when doing on your own and I have loved being a part of a more collaborative research style approach.’

(PARITY member F)

Maintaining Wellbeing

Our ethics application made explicit reference to monitoring health and wellbeing during the length of the study. Members were encouraged to share any concerns they had and encouraged to seek help if required. Taking care of each other during the project was crucial, as Comensus members already are aware of their existing physical and mental health conditions in addition to the new challenges of coping with a global pandemic. One PARITY member commented that:

'Taking part in this research project has been like a survival test. It has been a challenge; exciting and overwhelming at times. It has brought up past thoughts and emotions from my school days about my ability to learn new things. Peer and mental support have been key, alongside training and discussion to realise that others in the group felt the same. I am very glad I stuck it out as I’ve grown in my confidence about the project and as a person.’

(PARITY member C)

The group felt that breaking tasks down into small chunks and becoming aware of the diversity of knowledge and skills across the PARITY team supported and encouraged the group.

I have been involved in a number of research projects, but this one is the one where I felt most supported.’

(PARITY member D)

All the researchers acknowledged the benefits of keeping connected with each other during this period; several of the group lived alone and were grateful for the opportunity to communicate with each other on a regular basis and develop existing relationships:

'It kept me sane’.

(PARITY member E)

Challenges and impact of remote working on participatory research

The interviews and focus group had to be conducted online, so extra care was taken to ensure the meetings were recorded. Some technical issues included finding out that only the person starting the recording would have access to the file. It was decided for this reason that the interviewer should take responsibility for the recording part during the interview, so that the recording would be automatically emailed to them for safe storage, and that the other researcher would be able to ask the questions or take notes in the background. We reminded all participants about confidentiality, checked again for their consent, and explained that we would be recording via Teams and via an audio recorder for back-up. This was purely for transcribing purposes and recordings would be destroyed once the interview had been transcribed in a format suitable for analysis.

All the research group were enthusiastic about interviewing the sample of participants who had come forward. PARITY member F commented:

'Doing interviews on Teams rather than in-person has advantages and although you lose the personal contact, I think it is definitely an alternative that worked well. The added bonus was that Teams transcribed most of the interview as well as recording it’.

A new feature of Teams that was added at this time was the automatic publication of a transcript on completion of the meeting. Care had to be taken however to decipher the jumble of words and misrepresentations that this automated transcript often produced. Whilst some parts of the meeting would be reproduced well, others lost their meaning in a sea of erroneous words, phrases, missing audio and so on. The audio file of the interview was necessary as a final check, and on several occasions, to listen back and confirm parts of the interview.

The advantages of conducting interviews or meetings remotely did have some advantages: namely, the lack of travel time involved, no travel expenses incurred, and therefore easier access to interview participants. Conversely, not all participants had access to a computer or smartphone, so a telephone interview was arranged for this participant. This was the only interview conducted by a researcher on their own.

Some researchers struggled to complete the work allocated to them – either, due to other commitments, the challenges of remote working or failure to agree a suitable time.

'The coding part of process was really hard. But the results of it made it much easier to create survey questions. It took ages and was exhausting boring and difficult. But it all helped as survey created proves. Coding on spreadsheet way we did it was hard. It was a learning process. I would do it a bit differently if I could again. It all worked but it was confusing at times.

(PARITY member F)

This person began to work with another member and their partnership continued successfully for several weeks because they were able to meet in person:

It was great to be partnered with another member of the group, we could bounce ideas off each other, and we were more productive.’

(PARITY member D)

Our decision to add coded sections to an excel framework later, added more challenges for half the group as they were either unsure how to do this or lacked the necessary hardware (keyboard and mouse) to be able to do this. Others disengaged from the project at this stage due to ill health and waning interest, though we were pleased when they re-joined later to contribute to the tool development. Although remote working was mandatory in the beginning due to enforced lockdowns, remote working has become part of involvement practice now. However, the renewed facility for face-to-face gatherings from 2021 enabled PARITY members to continue various dialogues in person, including celebration of successes, the writing of papers like this (itself a participatory process) and contemplation of future involvement in research.

Future opportunities for participant researchers

One of the key principles of participatory research is the ability to develop partnerships and build capacity among the group. In this respect, we were pleased with the progress we made together and thankful to receive feedback like this one below:

‘Being involved with the Parity research group is radically different from the other tasks I do as a group member. Apart from recounting our lived experiences of health issues we are also considered to be stakeholders in the progress of the students training and education in the health and wellbeing school sharing our opinions and perspectives. Working with members of diverse groups culturally, sexually, and socially is of the most vital consequence in guiding our research project, because perceptual issues are originally at the personal level prior to how we think that about the physical world around us, especially in view of the state of the world today.’

(PARITY member B)

Another PARITY member commented that

‘The PARITY research study enabled me to further my knowledge and understanding of analysing data. This has enabled me to get involved in other research projects, writing sample questions for interviews, coding data, and presenting findings at a conference. This has all enhanced my understanding of research more generally’.

(PARITY member E)

Participatory research requires collaboration in all stages of the work. Following completion of the thesis stage, PARITY have risen to the challenge of creating posters, co-creating presentations, speaking at conferences and co-authoring articles for publication during a funded post-doctoral phase. All participant researchers reflected that they developed more confidence, learnt new skills and are conscious of a shift in their relations with other academics at the university.

Conclusion

Descriptions of service user and carer participation in research often relate to participation in qualitative data collection or participation in steering groups, as these can be more familiar territory for commissioners. Our group’s long-term engagement with the university and local research partners meant that they had been invited to participate in research and share their individual knowledge or experience (Voronka & King, 2023). As demonstrated above, this period was a phase of growth and development for the PARITY group as we engaged in co-learning and supported each other throughout. The impact of this on their self-confidence was immense, as described above, thus further shifting the balance of power between community and academia. A participatory approach can serve to enhance the authenticity and richness of the knowledge that is subsequently created, as well as enhance the university’s relations with the public.

It is necessary to emphasise the potential for future skills development and shaping of participatory research practice for the future. PARITY is keen to engage further with training on research skills. For those community researchers seeking employment and financial reward, grant funding has been used to offer a paid service user researcher role (Cahill, 2007; Happell & Roper, 2009; McKeown et al., 2012) where lived experience is seen as of equal value to academic experience. The PARITY group’s aspirations would be to access future researcher roles, including for some, paid researcher roles, to address any feelings of power imbalances.

As previously stated, we are mindful that this article focuses mostly on the participatory methods used during two early stages of our study; a description of the latter stages undertaken during 2021-22, and a presentation of the results, will be documented in subsequent publications.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all supporters and contributors at our university for their ongoing commitment to developing and sustaining partnership working.

Authorship

JG is a PARITY member and lead author, responsible for overall coordination and facilitation of this study and completed Professional Doctorate framed by this project.

SH, SM, EM, AM, RT are PARITY members, co-researchers and participatory co-authors of paper.

Funding

This project did not receive funding during the period described in this article. Later, in the post-doctoral phase, PARITY received funding in January 2024 from the university’s internal Quality Research fund for further development of the tool and the co-design of this report.