Introduction

Women living with HIV in Canada and globally have historically been marginalized and excluded from research as they have held limited power and positions of privilege within the broader HIV movement (Barr et al., 2024; Carter et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2016). This exclusion is partly due to how HIV activism rapidly evolved 40 years ago. Fed up with watching their friends, brothers, and lovers die with no rapid action by governments and regulators, predominantly cisgender (cis) gay men came together to demand greater acknowledgement and compassion for the emerging HIV epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s. While this activism led to the establishment of a desperately needed HIV research, policy, programming, and funding environment, the unintended consequence was that women living with HIV were excluded from the movement early on, a problematic reality with lasting impacts. By the time the public learned more about HIV transmission pathways and case numbers in women began to rise, a narrow HIV agenda for women had been set, primarily focused on women as mothers with aims to prevent vertical transmission of HIV. It has taken decades to slowly adjust HIV programming to meet the needs of affected women.

In this article, we describe a case study of the Women and HIV Research Program (WHRP), beginning with the need for such a program. WHRP is an intersectional feminist community-based participatory research (CBPR) program housed at Women’s College Hospital in Toronto, Canada. Our research program has collaborated with women (cis and transgender [trans]) living with and affected by HIV to dismantle the patriarchal narrative in HIV research since the early 2000s. We have used principles of CBPR and intersectional feminism (Combahee River Collective, 1977; Crenshaw, 1989, 1991) from WHRP’s inception, recognizing intersecting social categories that impact access to power, resources, and opportunities (Logie et al., 2011). This approach produced many successes in research and practice, including much interest from other researchers. As we are often approached to elaborate on our research methods, keys to our success, the concept of “community engagement”, and strategies for ensuring CBPR is meaningful, we now share a seven-step approach. While this approach is not meant to be linear, prescriptive, nor exhaustive, we intend for it to be a useful reference document for those considering or beginning CBPR in their own work. We conclude with reflections and recommendations for those embarking on the meaningful CBPR journey or seeking to improve existing CBPR programs.

The History of the HIV Movement and HIV Research

Women account for more than a quarter of all new HIV cases nationally (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2022). In some regions of the country, notably Manitoba and Saskatchewan, women now account for half of the incident cases (Government of Manitoba Department of Health, 2022; Government of Saskatchewan Ministry of Health, 2020). National reports show women have lower HIV awareness, treatment uptake, adherence, and viral suppression compared to men who have sex with men (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2022). Despite these facts, HIV resource allocation has not consistently recognized women as a priority community and the withdrawal of Canadian government funding has led to the closure of national and provincial organizations dedicated to women living with HIV leaving a gap in collective action for HIV prevention and care cascades. The disparities, particularly significant for trans women, are underscored by data showing high rates of mental health and chronic health conditions within this population (Lacombe-Duncan et al., 2023). Also, there is a lack of comprehensive data collection regarding trans, gender diverse, and gender expansive communities and individuals both in regards to HIV and beyond, emphasized by Viviane K. Namaste’s work (2007) on trans erasure. Overall this highlights the critical necessity to address these gaps to understand trans, gender diverse, and gender expansive people’s unique health needs, including HIV prevention and care (Lacombe-Duncan et al., 2023).

HIV research was one of the first research fields to adopt meaningful community engagement, exemplified by the Greater Involvement of Persons Living with HIV/AIDS (GIPA) Principles report discussed, signed, and released at the Paris AIDS Summit in 1994 (UNAIDS, 2007a). It drew inspiration from the earlier Denver Principles of 1983 (UNAIDS, 2007b), emphasizing the vital role of people living with HIV in decision-making processes and setting a precedent for inclusive health advocacy globally. The term “Nothing About Us Without Us” was adopted and became dogma in HIV research. GIPA quickly evolved to MIPA, “the Meaningful Involvement of People Living with HIV/AIDS” as people living with HIV recognized and resisted tokenistic involvement in HIV research and programming and demanded meaningful involvement. As women charted their own course within HIV research, the term MIWA – “the Meaningful Involvement of Women Living with HIV/AIDS” – was coined to ensure their reserved seat at the decision-making table. Carter et al. (2015) explored how to transform MIWA from a principle to practice through 11 focus groups where the concept of engagement surpassed mere involvement. The term MEWA, standing for the “the Meaningful Engagement of Women Living with HIV/AIDS”, has since replaced MIWA and been applied broadly in the HIV sector in Canada, particularly at community-based HIV organizations where people living with HIV mobilize community resources and create safe spaces to gather together.

MEWA and CBPR in HIV

CBPR approaches have been applied as far back as the 1940s (Macaulay, 2017). However, the emergence of the HIV epidemic in the 1980s was a particularly transformative time when this methodology was making waves in North America. CBPR is a collaborative approach to research born out of the fields of critical pedagogy, social psychology, and feminist and civil rights movement, particularly by Black feminist activists (Collins, 1990; Crenshaw, 1989; Davis, 1982; hooks, 1981; the Combahee River Collective, 1977). Although it should be noted that CBPR is not one unified approach (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020), one of the most fulsome versions of this process involves researchers and community members collaborating to identify the research questions, design research methods, collect and analyze data, interpret results, and disseminate findings together. Through shared leadership, community members and researchers partner in the research process and the knowledge, expertise, and skills each person brings to the team are seen as equal and complementary (Vaughn & Jacquez, 2020).

Globally, CBPR has been chosen by HIV researchers as a key approach to work with and make a difference for women living with HIV. Canadian researchers whose work is dedicated to women and HIV have been a leading force in this movement, which has been facilitated by the creation of unique funding calls specifically for CBR (community-based research; the more commonly used term in Canada) and HIV, including from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) starting in 2006. Some of the first HIV CBPR studies in Canada were led by members of our team, like Wangari Tharao, Claudette Cardinal and Renee Masching in the early 2000s on work through Women’s Heath in Women’s Hands Community Health Centre and Communities, Alliances & Networks (CAAN; previously the Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network) (CAAN, 2024; Tharao et al., 2006). Other leaders included Dr. Sarah Flicker and colleagues, who explored the perspectives from youth living with HIV and those working in community-based organizations. They found that while there was strong support for the GIPA principles in theory, practice lagged far behind (Flicker et al., 2008; Travers et al., 2008). Around the same time, Dr. Saara Greene and Ruth Ann Tucker co-led the Positive Spaces, Healthy Places study which examined housing stability and its relationship to health-related quality of life among more than 600 people living with HIV in Ontario (Greene et al., 2009, 2010). Dr. Greene’s subsequent work gave a vessel for peer research assistants (people living with HIV trained as research assistants; a term that has evolved in our own work to community research associates after much discussion) to share their experiences and explore the ethics of reciprocity in CBPR through reflecting on their studies (Greene, 2013; Greene et al., 2009). Our team was one of the first to lead a women-specific HIV CBR study in Canada (Logie et al., 2011; see The Beginnings of WHRP) which served as the catalyst for several large women-specific CBPR studies across Canada, including the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS, 2011-2018), Sexual Health & HIV/AIDS: Longitudinal Women’s Needs Assessment (SHAWNA, 2015-present), and the British Columbia CARMA-CHIWOS Collaboration (BCC3, 2021-present). Eventually, this women and HIV CBPR focus translated to a global level, with the World Health Organization (WHO) publishing the Consolidated guideline on sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV in 2019.

While CBPR has been a useful approach for research for women living with HIV, the lack of women’s voices at leadership tables, within funding agencies, and in policy and programming circles persists. This is exemplified by the limited representation of women in key positions, as noted in Canada, Europe and the United States such as the Canadian Association of HIV Research, where only four out of 17 presidents have been women – less than one one-quarter. Similar underrepresentation can be seen in organizations like the European AIDS Clinical Society and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of HIV Research, where only one of seven directors (14%) has been a woman. Similarly, the International AIDS Society (IAS) has only had five women as presidents out of 17 (29%) over 35 years. Notably, the IAS is making concerted efforts for gender equity at decision-making tables, as the president-elect is a woman and over half of their governing council are women. However, this progress is not reflected in Europe and North America. A more comprehensive effort to ensure that women are present in positions of power at decision-making tables is needed as it impacts where funding is allocated, what projects are pursued, and which guidelines are prioritized. With continued patriarchy impacting access to the HIV leadership tables, women will be left behind.

Case Study: The Women and HIV Research Program

The Beginnings of WHRP

WHRP began with a conversation between a clinician-researcher, Dr. Mona Loutfy, and a community leader, Wangari Tharao, both based in Toronto, Canada. Dr. Loutfy is a woman of color of Middle Eastern heritage and an infectious diseases physician who specializes in the care of women living with HIV. After working in the field for a few years, Dr. Loutfy became passionate about exploring the issues facing her patients, particularly those who were women living with HIV who were experiencing complexities not addressed in the literature or broader HIV community, including sexual and reproductive health and rights, high rates of trauma and violence, HIV disclosure and stigma, women-centred care and more. Wangari Tharao is a Black woman of Kenyan origin and the Research Program Manager at Women’s Health in Women’s Hands, one of the only community health centers in North America focused specifically on primary healthcare for Black and racialized women. Wangari Tharao saw the inequities facing African, Caribbean and Black (ACB) women living with and affected by HIV in the communities she served. From this vantage point she published the first study in Canada focused on ACB women living with HIV in 2001 (Tharao & Massaquoi, 2001).

In 2004, Mona and Wangari decided to embark on their first CBPR project together: Women Community-Based Research (WCBR): Involving Ontario HIV-Positive Women and Their Service Providers in Determining Research Needs and Priorities (Morshed et al., 2014). Running from 2007-2011, they sought to: (1) determine research needs and priorities for women living with HIV; (2) better understand women with HIV’s relationships with research and researchers; (3) and identify how to maximize women’s participation in HIV research (Morshed et al., 2014). In keeping with CBPR principles, twenty-one women from the community were hired and trained in research practices (Morshed et al., 2014). These women represented the diversity of the participant groups and were defined as “peers” in that they shared at least one of the defining commonalities of the research aim (i.e., gender, race/ethnicity, and/or HIV status) with participants. They received substantial training and took an active role in the project by recruiting participants and co-facilitating focus groups. In total, nineteen focus groups, including fifteen with 104 women living with HIV in five Ontario cities and four with 45 service providers in three Ontario cities, were held. Notably, most participants (> 90%) self-identified as racialized women (ACB; Indigenous; South Asian, and Latina) and participants also reported being involved in sex work, using injection drugs, and/or being part of the LGBTQ+ community – all groups that are under-represented in research. To us, this represents part of the power of CBPR: connecting with community and community leaders allows for meaningful engagement and consideration of groups often erased or made invisible. HIV stigma and discrimination, race, and gender were identified as priorities which informed the creation of a survey focused specifically on ACB women’s priorities (Logie et al., 2011). During the WCBR project, Dr. Loutfy officially launched WHRP at Women’s College Hospital in Toronto, Canada in 2006 with a focus on CBPR and intersectional feminism.

Conceptualizing “Our Community”

The word “community”, often designated in the field of HIV to those living with HIV, is actually much more complicated and can refer to many different populations and collective groups; therefore, defining what community looks like for each project or team is an essential step. We recognize that community can be based on identity or social locations (such as HIV status, gender, race, ethnicity), geographical boundaries or shared hobbies or interests. For us, we also see community and our collective work as a strategic way to gather political strength around a shared cause and focus. Our interdisciplinary team – and more specifically, the co-authors writing this paper - consist of women (cis and trans), gender diverse, Two-Spirit, and gender expansive folks who are living with and without HIV; academic and community researchers; advocates, clinicians, and front-line workers. We come from varied backgrounds including medicine, social work, public health, nursing, family science and human development, education, Indigenous health, community health, engagement, and advocacy. Collectively, we are Indigenous women, Black women, women of color, white women; we are lesbian, straight, queer, and Two-Spirit women ranging in age from 25 to 72, and much more. None of these categories are mutually exclusive or static. Women living with HIV are team members, community leaders and researchers, and front-line workers; some have completed post-secondary education programs before, during, or after working with our team. Some of us balance roles between community health leadership, academia and clinical practice. While the co-authors on this paper represent a core team that has contributed in varying ways to WHRP’s central projects over a decade or more, we acknowledge that many of WHRP’s projects involve many more essential people and we thank them for all of their contribtions to WHRP’s successes.

We have held discussions around how our definition of “community” relates to HIV status disclosure in our work. While we believe it is critical to acknowledge that members of our team (broadly and on this paper) are living with HIV, there is an ongoing need to consider if and how HIV status is shared. HIV is still significantly stigmatized in our world (Logie et al., 2011). Through the course of our work, we have had many team members publicly disclose for the first time; remain undisclosed throughout their work with us and choose to not be named on public-facing documents; be publicly disclosed and then later move to limiting their disclosures as their lives, professional endeavors, and families change and grow; and even disclose their HIV status intentionally and consistently as a form of advocacy (CC, JC, VN, BG). Due to the changing personal and public circumstances of each person, consent and comfort associated with HIV disclosure needs to be revisited with team members regularly. In our work and throughout this paper, we refer to “Community Research Associates” (CRAs) to specifically refer to women living with HIV who are also core research team members, and who may also hold many other roles discussed above. The term “community members” may be used broadly to talk about other collective groups and this is specified when it occurs.

Theoretical Grounding

To support the agenda for women and HIV, WHRP is rooted in the recognition of diverse feminist perspectives with its origins from the work of Black women including bell hooks (1981, 2000), Audre Lorde (1984), Patricia Hill Collins (1990), Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989, 1991), Angela Davis (1982), the Combahee River Collective (1977), among others. Feminism is not a monolithic ideology and has evolved over time in meaningful (and sometimes conflicting) ways, such as to include intersectional feminism (Davis, 1982; Massaquoi & Wane, 2007). Most feminist approaches include social and political movements that challenge and dismantle gender-based oppression and discrimination that have led to women and other marginalized genders having fewer rights, opportunities, power, and freedoms than cis men. Feminism seeks to transform social, cultural, and political normative structures that perpetuate gender inequalities, striving for a more just and equitable society for all.

In the HIV field, gender inequities and misogyny contributed to the initial inaction by governments to support people living with and affected by HIV in the early days of the epidemic. Sexual stigma, the devaluing and reduced access to power among sexually diverse persons, results in sexually and gender diverse men also experiencing gender inequity as they do not fulfill traditional masculinity norms (Herek et al., 2009). Gender non-conformity stigma, experienced when one does not align with traditional or conventional expectations of masculinity/femininity, is linked with increased social marginalization across all genders (Logie et al., 2011; Logie & Rwigema, 2021). As a renowned Black feminist, bell hooks (2000) declared, feminism is for everybody, as it challenges and aims to dismantle gender-based inequities, the result of which would also have immense benefits for boys and men (Equimundo, 2022).

Understanding the historical impact of colonization and the white Eurocentric nature of Canada, among other nations, intersectional feminism is a framework that recognizes and addresses the intersecting systems of oppression and privilege individuals experience based on their multiple intersecting and interacting social identities such as race, ethnicity, gender, class, sexuality, (dis)ability, education, and more (Combahee River Collective, 1977). Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989, 1991), intersectionality emphasizes that various forms of discrimination such as racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, and more are interconnected and mutually reinforced to reduce access to power, resources, and opportunities (Cho et al., 2013). For women living with HIV, intersectional feminism holds the potential to center and amplify the voices and experiences of groups who are often marginalized within mainstream feminist movements.

Intersectional feminism is essential for understanding the root causes contributing to why globally over half of the cases of HIV are among women and of those women, the majority are Black women, women of colour, and Indigenous women. The intersection of sexism and racism, as well as, homophobia, transphobia, drug use stigma, and sex work stigma is also relevant to explore and prioritize in the field of HIV (Lacombe-Duncan, 2016; Logie et al., 2011). Intersectional stigma considers multiple axes of marginalization and has been increasingly applied to understand the lived experiences of women with HIV (Logie et al., 2022; Sievwright et al., 2022).

Advocating for Reproductive Health and Rights

Responding to community priorities, WHRP began investigating several other research topics, including the reproductive health and rights for women and all people living with and impacted by HIV. At the time, in the early 2000s, many physicians were still discouraging people with HIV from getting pregnant and parenting, and the vast majority of fertility clinics refused to see a person living with HIV. In response, WHRP conducted a self-administered CBPR survey about fertility desires, intentions and needs among 490 women of reproductive age with HIV across Ontario between 2007 and 2009 (Loutfy et al., 2009). These findings, paired with the meaningful contributions from six community members and the guidance of Dr. Loutfy and Shari Margolese, led to the development of the first evidence-based Canadian HIV Pregnancy Planning Guidelines (CHPPG) in 2012 to assist people living with HIV in Canada with their fertility, preconception and pregnancy planning decisions (Loutfy et al., 2012). The CHPPG were updated in 2018 and the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society released their own guidelines on the topic in 2020, advocating for full fertility care for people living with HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C (Loutfy et al., 2018; Shapiro et al., 2020). The CHPPG are currently being updated for release in 2025 with a name change to the Canadian HIV Parenting Planning Guidelines.

Partnering with and being guided by Indigenous Women Leaders

Recognizing the disproportionate impact of colonization and the unique rights and relationships entrenched in Treaties and legislation in Canada, and anti-Indigenous racism among Indigenous Peoples and her clinic population, Dr. Loutfy reached out directly to the Ontario Aboriginal HIV/AIDS Strategy (Oahas), founded by and at the time led by the late LaVerne Monette in 2008. LaVerne was an Indigenous Two-Spirit woman and lawyer who founded Oahas as a nonprofit dedicated to providing programs to respond to the HIV/AIDS epidemic among Indigenous Peoples living in Ontario. LaVerne welcomed Dr. Loutfy as an ally and taught her about the history of colonization, genocide through residential schools and the continued mistreatment of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Most importantly, LaVerne emphasized the resiliency of Indigenous communities and showcased strengths-based and cultural approaches to working with Indigenous communities in HIV research. LaVerne and Dr. Loutfy’s collaboration led to an education session at the National Indigenous Women’s Gathering in 2008, which they subsequently shared across Ontario. Dr. Loutfy’s allyship with, and learning from Indigenous community leaders continues today through building relationships with organizations and community leaders, including the Feast Centre for Indigenous Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections (STBBI) Research, CAAN, and Indigenous research-community leaders, namely Doris Peltier, Carrie Martin, Renée Masching, Jasmine Cotnam, and Claudette Cardinal. Those partnerships inspired and formalized opportunities for numerous research projects focused on the well-being of Indigenous women living with and affected by HIV.

The Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS)

Through these long-standing, meaningful relationships, it became apparent that women living with HIV in Canada had unique needs related to their sexual, reproductive and overall well-being that were not being addressed by traditional models of HIV care. In 2010, foundational work cumulated in a monumental research project called the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study, or CHIWOS. This project, funded by CIHR, was led by Dr. Loutfy (Ontario), Dr. Alexandra de Pokomandy (Quebec) and Dr. Angela Kaida (British Columbia), along with over 100 partners across Canada, including those named above. Using CBPR principles, CHIWOS ran in five provinces: British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec. Each provincial team prioritized partnerships between local community members, organizations and researchers. The project began with a year-long formative phase to inform the development of a 2000-variable survey with nine sections. The development of each section was led by a woman living with HIV and an academic, with a broader team of community members, clinicians, and researchers contributing. After the formative phase, 39 women living with HIV from across the country were hired, trained and supported to be frontline CRAs recruiting, consenting, and administering the survey at three time points 18-months apart. CRAs brought forward a wealth of lived experiences and knowledge connected to the communities they identified with, and this led to successes in reaching and retaining women who are not typically engaged in research (Webster et al., 2018). CHIWOS remains the largest CBPR project with women living with HIV in Canadian history (Kaida et al., 2019).

Operationalizing CBPR in a large study was not without its challenges, which have been outlined in previous publications (Abelsohn et al., 2015; Loutfy et al., 2016). To meaningfully conduct CHIWOS as a CBPR study grounded in intersectional feminism and MEWA, many community advisory boards (CABs), steering committees and leadership groups were formed including an ACB Advisory Board and an Indigenous Advisory Board. Regular meetings and trainings, clear communication and roles, supportive team structures, and timely conflict resolution were prioritized and led to the overall success of the study from inception to ongoing dissemination (Loutfy et al., 2016; Watson, 2021a, 2021b). The data analysis approach adopted in CHIWOS was essential to the sustained commitment to CBPR and can serve as an example to others. Once data were collected, analyses and interpretation were co-led by academics and community members as partners, made visible by the inclusion of all CHIWOS team members on publications and authorship order established through an authentically inclusive strengths-based process. CRAs were invited to share the topics they were most interested in and/or had direct experience with, and they were engaged in (and inspired) relevant analyses. Another tangible way we ensured CBPR principles were carried throughout the project is the co-presentation of nearly all CHIWOS conference abstracts by both a researcher and community member or by a community member alone. In the spirit of supporting others who endeavor to undertake such large CBPR projects, all documents from CHIWOS are publicly available, including the CRA training manual, policies and guidelines, slides for steering committee meetings, and the actual survey questions (www.chiwos.ca).

Other WHRP Activities

The work from CHIWOS has led to several other CBPR projects under the umbrella of WHRP. These include work conducted by the Trans Women and Gender Diverse People HIV/STBBI and Health Research Initiative (TWIRI, formerly the Trans Women and HIV Research Initiative; www.TransWomenHIVResearch.com), in the area of Women-Centred HIV Care, and population-specific projects with Indigenous and ACB women with HIV. Many smaller projects on topics like menopause, trauma, infant feeding, and aging have been conducted by or with the WHRP team, using CBPR, anti-oppressive, and intersectional feminist approaches, with a focus on training and mentoring students, early career researchers, and community learners and leaders. Many of these projects are growing, with future potential for large societal impact. A general CBPR process of 7 steps has emerged from conducting these projects (Figure 1).

WHRP’s Seven CBPR Steps of Meaningful Community Engagement and Partnership

While some research teams have summarized their steps of community engagement in building community-academic partnerships (Liu et al., 2022; Sayani et al., 2022; Turin et al., 2022), it is still rare for the details of the steps and practicalities to be provided for others to operationalize. Seven CBPR steps have emerged as the pattern for conducting community-engaged and community-partnering research at WHRP, which we expand on in detail below in hopes of supporting others to operationalize community engagement and partnership successfully.

Step 1: Reflection

The starting point for any researcher who wants meaningful community engagement and partnership is “Reflection”. Some key reflection questions as a researcher include: “What do you know about the community you want to research?”; “Why are you interested in doing this research?”; “Which communities and/or community members will it impact?”; “Who’s voices are missing?”; “Will the research benefit or harm the community?”; “What is the overall goal of the research?” Researchers need to reflect honestly on their intentions, their goals, and their potential fit with the proposed research and community. Understanding your positionality, how you identify with the community and research topic, your intentions, and what makes you a good candidate for researching your selected topic with a particular community is essential before beginning. Identifying your own assumptions about a community (positive and negative) can also elucidate where you may need to challenge yourself to learn more. In CBPR, it is also not just about the end result – the process matters. Reflecting on how much you can properly engage with community throughout the research process (particularly given time, financial, and institutional constraints) is also important to consider before intiating a CBPR study and these constraints may make it impossible to do CBPR in a meaningful and supportive way. Regardless of potential scientific benefit, researchers considering CBPR need to understand that not every research idea will be a good fit for them, the communities they are interested in, or CBPR for various reasons.

The concepts of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) are buzzwords and now expected to be considered by all research groups. However, to meaningfully engage and partner with the community, particularly communities that have historically been oppressed, researchers need to go beyond EDI and reflect on the real needs, goals, and impacts of their planned research. If the research does not come from community needs and will not benefit the community, or if it may in any way harm the community, continued reflection on whether (and how) it is best to proceed with the research project may be needed. As an example, one of WHRP’s first projects, the WCBR project, started with reflection on the potential impact of the research on Black and/or racialized women. Also, the educational sessions with LaVerne Monette and Oahas started with reflections on the potential impacts of research on Indigenous women living with HIV and their communities. Reflection pointed to the likely benefits of the work, and the projects went forward. At WHRP, when the reflection highlights concerns or a lack of meaningful benefits for the community, projects have been reconceptualized or halted.

Step 2: Background Learnings and Preparations

Researchers should not proceed with contacting communities, members, and leaders without having engaged in appropriate background work, learning, and preparation to the best of their ability. Without this foundational work, researchers risk causing harm to communities even if it is unintentional. Examples include not being aware of acceptable language and terminology used within communities, overlooking customs or traditions required when approaching an Elder or community leader, or lacking familiarity with how research is understood within a community, including histories of medical research mistreatment and resulting mistrust.

Background learning should be rooted in trauma- and violence-informed practices and research (Nonomura et al., 2020; Straatman & Baker, 2022). Such approaches acknowledge the pervasive nature of violence and trauma in our society and its disproportionate effect on marginalized groups (Elliott et al., 2005). Adverse Childhood Events (ACEs) and various forms of violence in adulthood, including intergenerational violence against Black, Indigenous and other people of colour related to colonization, genocide and slavery underscore this reality (Bombay et al., 2009; Felitti et al., 1998). Immigration to Canada often stems from the consequences of colonization, war, violent conflict and occupation (Beiser, 2005), while structural violence persists through patriarchal and racist laws and systems (Farmer et al., 2006; Sharif et al., 2022).

Understanding social determinants of health is vital, given how trauma and violence can intersect with economic, educational, healthcare and community disparities, which can pose significant barriers to participation in research (Hankerson et al., 2022; Kirkinis et al., 2018). Under trauma- and violence-informed principles (Harris & Fallot, 2001), researchers would need to understand the pervasiveness of this violence and trauma and how it impacts peoples’ well-being in all dimensions of their life and work. The researchers aim to create emotionally, culturally, and physically safer spaces for all and consciously aim not to retrigger or retraumatize. WHRP has begun using the term “safer spaces” instead of “safe spaces” to acknowledge that for many, no space is completely safe. Creating these spaces can involve practical considerations about the physical space, such as where meetings will be held, the availability of gender and ability-inclusive bathrooms and preparatory walkthroughs in research spaces with community partners to address any concerns.

WHRP prioritizes creating safer spaces by conducting background learning and preparation to facilitate informed discussions and address power differentials. Our work has required an understanding of Canada’s colonial history, including residential schools, the apprehension of children from Indigenous parents in the sixties until today, and the history of the Indian Act, treaties and unceded stolen lands. The Truth and Reconciliation Report of Canada (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015) is a required reading in our team for the preparation of partnering with Indigenous communities. Knowledge of colonization’s impact on Black communities, including an understanding of transnational feminism, has also been crucial (Collins, 1990).

Recognizing the diversity within Black and Indigenous communities, we practice cultural humility to ensure inclusive research processes within and between groups. In the past this has included implementing harm reduction practices such as offering a counsellor, healer or Elder as needed on projects. Our commitment to learning from past experiences emphasizes the importance of thorough preparation to prevent harm and re-traumatization, with a dedication to recitfying mistakes and continuous improvement moving forward.

Step 3: Relationship Building

Another important step to meaningful community engagement and partnership is relationship building. In the case of a researcher not initially having any relationship with the community they want to work with, reaching out to colleagues who do have connections and asking for introductions is an appropriate first step. Making “cold calls” is also completely acceptable. This requires finding out who the relevant community leaders are, such as the executive directors of associated community-based organizations or grassroots community organizations. When considering with whom is best to build relationships, researchers should ensure 1) people with living/ed experience and 2) community-based organization leaders who work in the field are contacted. Once contact has been made and a response has been given, take the opportunity to meet (via phone or videoconferencing) and/or in person if possible and at the preference of the potential partner. The key to the initial meetings with community members and leaders is to listen: to their points, to their needs, to their ideas. Explain your social positionalities and intentions, using your past reflection work as a guide. Through conversation, there can be a mutual assessment of shared purpose and goals. Listening during this phase serves as a needs assessment to determine if the community wants to work with you, if your interests align, and if you are, in fact, a good fit to collaborate. If there is hesitancy on the part of the community organization/member, listen to their concerns and return to the reflection phase: are you the best person for this research? What are you hearing from the community? It can be difficult to shift priorities, but some relationships may not work and researchers need to understand their power in these situations and accept that they, or the community partner, may not be ready for the project or fit well together.

If all aligns, you must be willing to focus on the key areas from the community’s perspective. Understand that the initial meetings are just the beginning as the next critical aspect of academic-community relationship is trust-building. Trust is something that is earned and requires time, actions, and commitment. Examples of activities that build trust are being available to give presentations to the community about your topic of expertise and providing other forms of community service, such as volunteering. Another is listening to community members’ feedback and recommendations openly, and incorporating them. To have an ongoing trusting relationship and partnership with the community requires time, meetings, connection building, and reciprocity and it is likely the most rewarding aspect of academic-community partnerships. As partners, community members take roles like co-principal knowledge users/investigators (PKU/Is), knowledge users (KUs)/co-investigators (co-Is), collaborators, research associates, coordinators, and advisors – not solely CAB members. While CABs have their role in providing broader community perspectives and support, they do not signify a direct path (or the only path) to meaningful CBPR. For all community partner positions, having terms of references and clear expectations are key. Being clear about the time commitment, roles, and the reimbursement structure are important aspects of setting expectations. Start out by making the terms of reference and/or job description(s) with the role(s) clearly laid out and, when appropriate, send out the invites widely and aim for diverse members. Often, different community members will be involved at all levels in a project – some community leaders will be PKU/Is or KU/co-Is while others will work as research associates, and other community members will be on the CAB. This multi-level community involvement and partnership creates opportunities for people with a wide range of experiences and priorities to participate in ways that work best for them and the project.

Step 4: Developing Fair and Transparent Team Structure and Procedures Together

As outlined in Loutfy et al. (2016), principles of CBPR, GIPA, and MEWA were used to engage women living with HIV and community leaders to develop the overall vision, mission, guiding values, and frameworks for CHIWOS. Clear and transparent study procedures and policies which included these values and guiding frameworks were created and shared for feedback from academic and community partners alike (https://www.chiwos.ca/cbr-resources). Such study procedures and policies had to be flexible and open to change if recommended by community members, making the policies and procedures “living documents”, reviewed annually. While these items, documents, and policies were being developed, a shared team structure was collaboratively developed (CHIWOS Research Team, 2024). Team structures can develop, grow, and improve over time.

Recently, WHRP received CIHR funding to be one of 10 Women’s Health Research Hubs in Canada. The team structure diagram for our emerging hub places women living with HIV in a leadership role in the center, as the work is for them and they should be guiding it (Figure 2). The hub’s structure involves community-based organizations, researchers and women living with HIV as equal partners, as PKUs/co-PIs and KUs/co-Is. To ensure CBPR principles are used by all, an “Operations Manual” outlining the vision, mission, guiding frameworks, values, and steps was created and disseminated after input was obtained from community leadership. In this Operations Manual, there are examples of: community member engagement roles; example CAB terms of reference; example agendas, minutes, job descriptions and team presentations; ways to proceed with community engagement and dissemination. The Operations Manual also outlines the importance of, and recommended amounts for, community reimbursement. Appropriate remuneration (i.e., the amount and methods of payment) for community members’ contributions is a core principle of CBPR. Further, a potential plan of action to take when conflict or inadvertent psychological dysregulation occurs was important to include in the manual similar to the Emotional Support Policy that was created for CHIWOS. The CHIWOS Emotional Support Policy consisted of a Support Tree where each CRA was paired with a Buddy, and all CRAs could access a line of support that included the coordinator(s), the PI(s), an Elder, and a counsellor if needed.

Step 5: Multi-directional Training and Learning

Academics have much to learn from community members. For example, if researchers intend to work with and/or include the experiences of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, engaging in training and education regarding the experiences of the First People of this Land by Indigenous Peoples themselves is a critical first step in the research process and a move toward truth and reconciliation. As outlined by Indigenous scholar Dr. JoLee Sasakamoose in the Indigenous Community Responsiveness Theory (Sasakamoose et al., 2017), recognizing the value of Indigenous healing practices and partnering with Indigenous healers, Elders, knowledge keepers, scholars, and Peoples are important to support the self-determined health, education, and governance of Indigenous Peoples. This process benefits Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous allies alike.

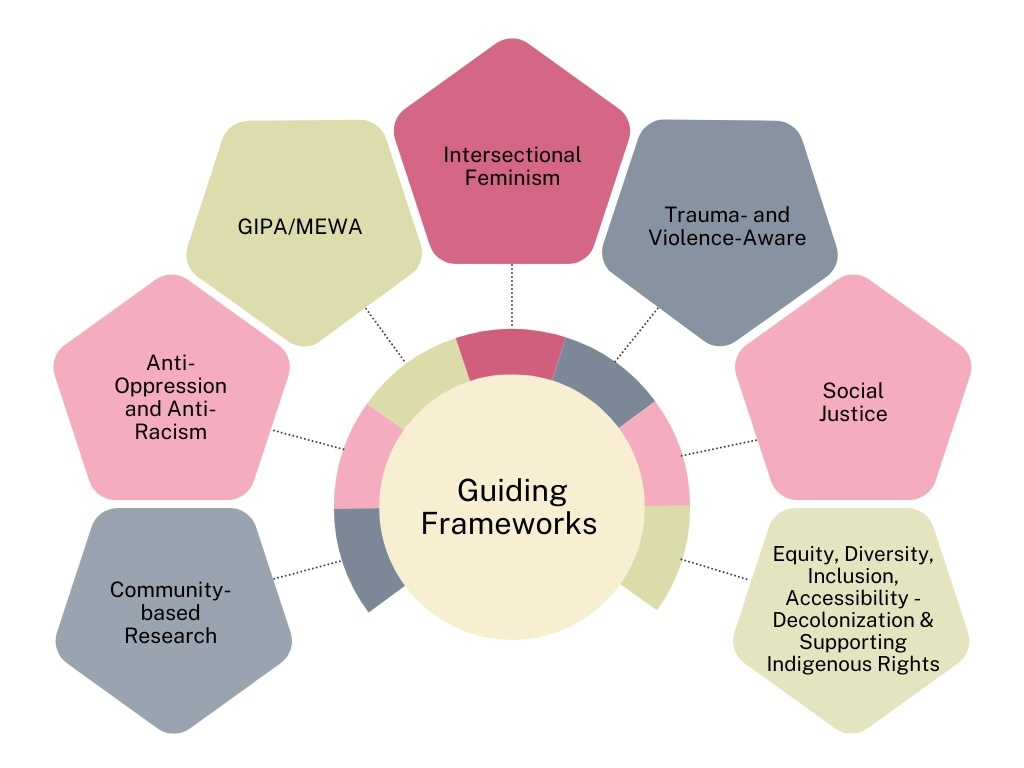

For CHIWOS, initial training for all team members – researchers, community members, and clinicians – was key, and it involved teaching about the CBPR approach and guiding frameworks including CBR, intersectional feminism, GIPA, MEWA, social justice, anti-oppression and anti-racism, trauma-and violence-aware care, and equity, diversity, inclusion, accessibility, decolonizing and supporting Indigenous rights (EDIA-DIR) (Figure 3). When team members understand how HIV-related stigma, other forms of intersectional stigma and discrimination, and potential trauma may affect women living with HIV at individual, community, and structural levels, the drive and desire for social change heightens. Multi-directional training includes training on research ethics principles in the Declaration of Helsinki and other relevant ethical structures, like the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS-2) in Canada. Training on the steps of research and the practicalities of conducting research as a team, such as ethical recruitment, consenting, survey, interview, or focus group conduction, and research analyses, has been integrated into our initial trainings for researchers, trainees, and community members alike. As projects roll out and evolve, it is imperative to revisit training needs and offer updated or current training opportunities. In 2020, for instance, our team responded to the attention on anti-Black racism following the murder of George Floyd and hired an intersectional feminist educator to offer anti-racism and anti-oppression training to all of research team members, partners and trainees.

Step 6: Roll Out

It is only when one has made strides with Steps 1 to 5 that one can really roll out their project using community engagement and partnership, highlighting the importance of taking time to do research in “a good way” (AHA Centre, 2018; Flicker et al., 2015). Doing research in a good way is an Indigenous research concept that the CHIWOS team reflected on in a recent paper (Peltier et al., 2020). Rolling the research out in a good way involves all of the previously mentioned steps, along with specific attention to communities most affected – including Indigenous Peoples. CHIWOS had an Indigenous Advisory Board that reviewed all parts of the research process. In keeping with the First Nation mandate of Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP®) (First Nations Information Governance Centre, 2014) and the equivalent Métis and Inuit guidance, the CHIWOS team held a Ceremony to transfer the data given by the Indigenous women involved in CHIWOS to their research partner, CAAN, a national Indigenous HIV community-based organization (CAAN, 2024).

Rolling out the research project as outlined in the study protocol and approved by a Research Ethics Board (REB) is a significant step to reach when conducting CBPR. It must also include an iterative process such that if procedures that are not good for the community need to be altered, they can be and that may require REB amendments. As an example, in one of the WHRP’s TWIRI projects, focus groups were planned with trans women living with HIV. Despite meaningful community engagement throughout the design of the project, we did not anticipate that women may prefer semi-structured one-on-one interviews. Following feedback from our Community Research Coordinator (a trans woman) and potential study candidates, necessary revisions were made to the protocol to change from focus groups to one-on-one interviews and the study’s ethics application was amended. Using anti-oppression principles in the rollout is key, and the team needs to frequently reflect on power imbalances and mitigate them as much as possible. Further examples of how we engaged in this process, specifically within TWIRI, have been previously published (Underhill et al., 2024).

Step 7: Getting Feedback and Bringing the Findings Back to the Community

Through experience, we have learned that the next step in this process is having multiple avenues of feedback throughout the project available for all team members. Incorporating the feedback provided is a key contribution to the continued trust building and explaining the updates and improvements via newsletters and meetings is important.

The idea of co-creation of research outputs is relatively new and evolving and, in the past, has been called different terms such as integrated knowledge translation (IKT) (Kothari et al., 2017) or knowledge translation and/or mobilization (KT/KM). Co-creation takes the concept of IKT to a further level by not just involving the community early on as important stakeholders but to consider and work with the community in the co-creation of new knowledge and dissemination of that knowledge as partners. Co-creation has the opportunity for greater impact as community members at the frontline can bring the findings back to the community as their own. This knowledge-to-action approach with a social justice focus can narrow disparities, eliminate inequities, and improve the health of all. At WHRP, this is partly done by involving community members in developing analysis plans, analyses interpretations, manuscript writing and publications, and conference and other presentations. Involving community members in developing analyses plans and interpretations require training and the training is an important capacity-building piece that can promote future opportunities with other research projects for CRAs. All of these steps are fairly compensated.

Taking the findings back to the community is another essential step to build trust between academics and community members and the community-at-large. While this can happen through the form of webinars, toolkits (e.g., Women-Centred HIV Care toolkits, available at https://www.cep.health/clinical-products/hiv), community talks, infographics, and more, there can also be more creative and non-traditional modes of IKT through community-led initiatives. In one instance, WHRP was able to secure funding to have a completely community-led IKT initiative where four community members (women living with HIV who we trained in IKT; Knowledge Translation and Exchange Champions) were paired with an academic and a coordinator to learn more about an issue that mattered most to them, design an intervention to address it within their community, and receive full training and support to actualize their intervention. The initiative led to a short-term self-care program in one community; an ongoing, interdisciplinary conference prioritizing trans women and gender diverse and gender expansive communities, aimed at clinicians, researchers, and community members (https://www.transwomenhivresearch.com/viewingparty2023); a community-feedback project that informed further developments to the Women-Centred HIV Care Model; and an anthology created by community to give more context to CHIWOS statistics (https://www.chiwos.ca/_files/ugd/54ef62_e4027969b8434bcaae94e5aad061a097.pdf). Each of these projects centred the Knowledge Translation and Exchange Champions and their personal communities, highlighting how community-led initiatives can reach groups of women that may not be specifically selected for outreach by more general research IKT efforts.

Developing action plans based on research findings is an integral part of this process, ensuring that the insights gained are translated into tangible steps for positive change. These action plans often involve collaboration with community stakeholders to implement interventions, policies, or programs aimed at addressing identified issues and promoting health equity. The iterative nature of this approach allows for ongoing adjustments, emphasizing the dynamic relationship between research, community engagement, and meaningful, sustainable outcomes.

Returning to Step 1: Reflection

As outlined in Figure 1, the steps are cyclical and can be considered to be occurring simultaneously, iteratively and repeatedly. Repeated reflection is central to success: Why are we doing this? What have we learned and what can we improve and grow? Are we contributing to the community in a good way? Reflecting on whether true listening has occurred is key and whether trust has been kept is important.

Discussion

We have reviewed in detail our seven-step CBPR approach of community engagement and partnership that WHRP projects have undertaken to date to lead to successful, collective, community-academic research co-creation, dissemination, and uptake. Importantly, while these seven steps reflect our current practices, community engagement and partnerships in research are not static; the steps and considerations keep evolving and deepening over time based on all our team members’ needs, and we look forward to seeing this done by our team and others in different ways in the future. This article is not meant to highlight that WHRP has been without flaws in its endeavors of community engagement and partnership. Rather, we acknowledge the many mistakes made over time and show gratitude to the community partners who have helped us learn and grow from these mistakes, and have continued to work and grow with us. In this paper, we have shared our learnings and current process – and note that some of these were born out of the growing pains of CBPR. Chávez et al. (2008) describe CBPR as a dance where there is a need to continuously learn to dance while accepting the inevitability of mistakes. This requires a willingness to accept accountability and learn from these mistakes. It has been our experience that this accountability is key to long-standing community partnerships.

Understanding how one’s social positionalities impact CBPR has been an ongoing lesson for our team. Self-reflection on positionality has become an essential practice in our team for everyone, including academics and community members. Positionality is a person’s understanding of how the identities they have (such as their sex and gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, social privilege, migration status and so forth) are socially categorized and unavoidably influence their opinions, values, and experiences. Our positionality impacts how others engage with and treat us as people, and also how we engage as researchers. Engaging in reflexivity as research team members is necessary to understand how these varied and intersecting identities may inform the research we are drawn to, the methods or methodologies we take up, and how we interpret study findings. This reflexive process is not intended as a way to eliminate the influence of our positionality, as this is not possible; instead, it can heighten awareness to understand our relationships with communities, research and data. For WHRP, reflexivity is critically important as we are engaged with several community groups (e.g., CAAN, Women’s Health in Women’s Hands) to which we may not all belong. Attention is paid to who is at each research team meeting, who is part of the working groups, who we may be missing, and how our positionalities are understood individually and collectively.

Despite the success we have had using this framework to engage in community-based partnerships, it is important for other research teams to be aware of the obstacles that exist to doing this work in a meaningful way. Paternalism is built into the systems we exist in – systems that are necessary to navigate as researchers in Canada. This includes research institutions, higher education institutions, and funding agencies. Research programs related to women’s health are often underfunded, which can make compensating community members properly difficult. Given the project-based funding model of many research funding agencies, it is up to the person(s) leading the CBPR work (nominated PI/PKU) to ensure funding is allocated adequately for research support staff, community honoraria, knowledge translation, and other study-related costs. This speaks to the importance of having realistic research project goals and being clear about the resources available when engaging community partners. Some partners may turn down the opportunity to collaborate if there is not sufficient funding to compensate them at the rate they deserve. It is the researcher’s responsibility to advocate for improvements to the regulatory and funding aspects of research to minimize bureaucracy and make engaging in CBPR as accessible as possible for the community.

While we reflect on the challenges and lessons learned, we are proud of our successes, particularly those that have impacted people’s lives for the better. For example, in the early 2000s, WHRP collaborated with partners in the area of fertility care to explore access to fertility care for people living with and affected by HIV across Canada. We found that access to infertility investigations and treatments in Canada was limited and regionally dependent. To improve access to evidence-based fertility care, we then used a CBPR approach to develop the CHPPG publication in 2012. A subsequent iteration of the CHPPG (2018) continued to advance this important area of care for people living with HIV. Our current focus has also expanded to a collaboration that is undertaking a policy analysis of relevant legislation and standards that continue to hinder access to assisted reproductive technologies for people living with and affected by HIV.

Another notable success is that women living with HIV have shared the impact CHIWOS had on their sense of community and autonomy, and on their access to care. From the Women-Centred HIV Care Model developed by CHIWOS, hundreds of healthcare providers have been trained in providing trauma-informed, person-centred holistic care for women living with HIV. Over the years, many CRAs who were a part of CHIWOS and WHRP have gone on to obtain undergraduate, master’s and PhD degrees, as well as graduate from several diploma and professional training programs. Many are still working in the HIV field as peer leaders, support workers, coordinators, and/or researchers. All are blazing their own path, and many have attributed their success in part to WHRP’s capacity building efforts and that of our partners who have become an integral fabric of the work of the program.

We recognize that given our specific experience in the HIV field, some of our insights may not apply to other fields. HIV research is much ahead of other disciplines in advanced CBPR and community engagement which makes it a field to learn from. Each research team is starting from a different point, so we recommend that these 7 steps be adapted to work with what best fits for your team, your research, and the community partners that you are working to engage.

Conclusion

Over the past two decades, WHRP has created strong community-academic partnerships that set the bar for the engagement of women with HIV in research. The 7 CBPR steps our team has taken to build and maintain these partnerships is not just relevant to the field of women and HIV – it can be applied broadly to other fields where research teams are aiming to emphasize community voices and impact.

We have identified obstacles to implementing these 7 steps, many of which result from systemic inequities experienced by structurally marginalized communities. This is where allied researchers willing to use their positional power comes in. We have demonstrated how we advocated for progress at the institutional level and acknowledge this is a slow, difficult and often political process.

Our goal is to inspire other teams to critically examine how they will mitigate power imbalances and to share their self-reflection on how they carry out meaningful community engagement and partnership. This paper represents a call for continued advocacy for Women’s Health Research funding and the meaningful engagement of women in research in general, with attention paid to intersectionality. If we are to accelerate the changes needed to address the gaps that exist for women’s health, those of us with power must be willing to continue to highlight the negative impact of patriarchy and misogyny on individuals, within institutions, and across society as a whole. We encourage researchers from all backgrounds to join us in shaping an equitable future where women’s health and well-being are prioritized.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, The Women and HIV Research Program Team would like to acknowledge and honour all of the women living with HIV who have been involved in any aspect of our work; from research team members, Community Research Associates to Community Advisory Board members to study participants. We honour your wisdom, trust, and partnership. We would also like to acknowledge all of those involved in the research teams for the various projects mentioned in this manuscript, including the Women Community-Based Research (WCBR) study, the Canadian HIV Pregnancy Planning Guidelines (CHPPG) Team, The Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS), CHIWOS-PAW, and the Trans Women HIV Research Initiative (TWIRI). Thank you to Women’s College Hospital’s Research Institute for their institutional support as we have innovated, grown and pushed the boundaries with this research program and within the institution.

Disclosures

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The Women and HIV Research Program (WHRP) is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation Grant (FDN154325). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.