A truism of translational research is that it takes too long for research findings to contribute to practice and policy change, with scientists offering varied estimates of the time it takes for evidence to be integrated into practice settings (e.g., 15-17 years; Balas & Boren, 2000; Hanney et al., 2015; Khan et al., 2021; although the literature suggests lags of 50 or more years, depending on topic and outcome of interest; see Morris et al., 2011). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) and other community-engaged research methods strive to shorten that time by involving those who are most affected by a health issue or risk factor and other relevant parties from the start, including planning for action and impact (Wallerstein et al., 2017). As a complement, dissemination science emphasizes the importance of having a proactive strategy to increase the likelihood that research has an impact. However, there have been few published frameworks or trainings to guide community-engaged research teams in proactively planning for dissemination activities to create impact (Cunningham-Erves et al., 2020, 2021). This article aims to fill this gap by describing the dissemination planning curriculum and process used by a national program of interdisciplinary health equity researchers utilizing community-engaged research approaches.

The field of dissemination science has produced abundant evidence supporting the premise that to achieve maximum impact, researchers must engage in early and proactive dissemination planning processes (Contandriopoulos et al., 2010; Lavis et al., 2003; Mitton et al., 2007). Often called “designing for dissemination,” such principles include establishing an early dissemination plan, working with community partners and affected parties to identify effective formats and timelines for sharing results, and strengthening relationships with research end-users throughout the research process. These types of approaches are thought to be critical for improving the low rates of dissemination activities and impact currently seen in public health (Brownson et al., 2013; Kwan et al., 2022) and are increasingly part of training activities (see, e.g., Padet et al., 2018; Rakhra et al., 2024). Some major U.S. funders have started requiring such plans or supporting dissemination efforts; however, others have no such policies or resources in place or require only academic-centered dissemination (McElfish et al., 2018). Despite growing attention to the importance of dissemination, too few researchers engage in these planning processes (Brownson et al., 2013).

Ideally, community-engaged research teams would undertake proactive and systematic dissemination processes more routinely and robustly than traditional researchers. After all, such research approaches are premised on the imperative of engaging authentically with the communities most affected by the research and producing both knowledge and action (Wallerstein et al., 2017). While work documenting the process of community-engaged research frequently references dissemination, the focus is often communicating research results back to participants, versus a fuller range of audiences who are impacted by or can impact the work or issue (see, e.g., Concannon et al., 2012). Indeed, one survey of community-based participatory researchers noted that 98% reported results back to participants (Chen et al., 2010). As a response to unethical, extractive research practices, such community-based dissemination is critical (Mayo-Gamble et al., 2022; Purvis et al., 2017). However, to achieve maximum impact – and ultimately the needed policy and practice change to shift systems and structures that impede population health and health equity – dissemination must also target additional audiences beyond research participants, with systematic attention to the power dynamics in a community that can facilitate change processes. For instance, reaching community organizers, lobbyists, advocates, and/or policymakers directly with community-grounded research results has the potential to accelerate movements for change (Ashcraft et al., 2020; Iton et al., 2022; Pastor et al., 2018).

Recent years have seen much-needed attention in peer-reviewed articles to dissemination processes for community-engaged participatory research (Cunningham-Erves et al., 2020; Purvis et al., 2021). For instance, Purvis and colleagues described a dissemination protocol for their CBPR project with Marshallese Pacific Islanders, outlining the steps the project team used to define audiences, content, mode, and timelines, and engage community throughout the process (Purvis et al., 2021). Cunningham-Erves and colleagues (2020) described a framework for community-engaged research dissemination, including phases for planning and implementation. Both articles emphasize incorporating community engagement throughout plan development, using a multi-phased plan that begins with outlining goals and audiences and then implementing the plan, with iteration as needed. A recent review by Luger and colleagues (2020) highlights outcomes of participatory research that include sharing of information and resources, achieving group goals, and demonstrating benefits of and satisfaction with the project (Luger et al., 2020). Longer-term assessments, including improvements in the uptake and use of research, changes in practice and community settings, and impacts on health outcomes, are suggested as important additional assessments, and the strength of dissemination activities can be tied explicitly to these (Luger et al., 2020; Ramanadhan et al., 2024). Similarly, models of CBPR, such as that developed by Wallerstein and colleagues, emphasize outcomes that can be influenced by dissemination activities, including in the medium-term (e.g., changes in policy environments and power relations) and the long-term (e.g., achieving goals related to social justice and health equity) (Wallerstein et al., 2008).

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Interdisciplinary Research Leaders (IRL) program launched in 2016 to support action-oriented community-engaged health equity research in communities across the United States (Gollust et al., 2022). Fellows enter the program in teams of three (two interdisciplinary researchers and one community-based leader) in topical cohorts each year. The program provides a research grant and a virtual and in-person curriculum. The curriculum includes attention to four domains: leadership (including leadership in equity, diversity, inclusion, and anti-racism), research methods (including qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research), community engagement and collaboration (including grounding in CBPR, considerations of ethics and equitable and effective collaboration, as well as conflict management), and policy and communication (including advocacy principles, data visualization, and dissemination planning) (see Gollust et al., 2022 for a complete description of the curriculum).

This article presents the components and evolution of dissemination planning activities all teams proactively completed at the outset of the research process. Our objectives in this manuscript are to 1) describe the curricular components that support research teams’ dissemination planning processes; 2) share a protocol that other community-engaged, action-oriented research teams can adapt for proactive dissemination planning; and 3) describe the high-level dissemination planning themes and initial strategies of 15 research teams that went through the training and dissemination planning process.

Methods

Curricular Components

The dissemination curriculum in the first year of the program had three components: 1) a didactic set of lectures delivered virtually; 2) a dissemination planning template that teams completed; and 3) in-person workshops. The program’s stated learning objectives related to this curriculum domain were to articulate principles of effective dissemination, identify their core audiences, and create a dissemination plan and timeline. The didactic components launched with an initial webinar that highlighted the importance of proactive dissemination and introduced the dissemination planning template. Then, teams could explore five, self-paced 10-15-minute videos that presented high-level principles of dissemination science, the importance of relationship building with research end-users, the possibilities of social media, and promising practices for translating research in formats beyond academic articles. The curriculum was developed through a partnership between faculty and staff at an academic School of Public Health and a non-academic organization that serves as a broker between researchers and health policy and practice (see Appendix A for details on the partnership and Appendix B for an outline of the course and workshop contents). The co-leaders of each of these curriculum elements are all authors on this manuscript (KR, BC, SG, and SR) and come from distinct backgrounds from practice and academic communities, including public relations, communication, implementation science, and health policy communication. A subset of team members (SR, SG) routinely conduct community-engaged research.

The dissemination planning protocol drew on an existing resource (Sofaer et al., 2013) and was adapted to the teams’ contexts of participatory health equity research. Teams were instructed to complete the six-section template (Table 1) within the first two months of the initiation of their research project funding, and to complete it with relevant community partners and/or advisors. Draft plans were reviewed by a pair of reviewers from different disciplinary perspectives (authors on this paper). Teams were given feedback and asked to consider the protocol a working document that they would revise throughout their three-year research process, through iterative discussion and engagement with community members and representatives of their target audiences.

At the end of the first nine months of the fellowship (and four months into the formal initiation of research projects), teams participated in an in-person (when COVID-19 conditions allowed) workshop. They attended two, two-hour trainings, one on communication and messaging with a focus on understanding audiences, and the other presenting principles of dissemination and implementation science with a focus on health equity (Appendix B). Both workshops were interactive, incorporating details of the teams’ projects and draft dissemination plans.

Interaction with fellows over the first five years of the program (2016-2021) and review of annual evaluation data led to specific changes in the curriculum to deepen its centering on equity. Specifically, curriculum leaders began drawing more explicitly from work on community organizing in considering models of policy change and key community-based audiences for research (Minkler & Wakimoto, 2022). Workshop leaders began to implement a more explicit emphasis on the role of power in communication and dissemination, and specifically how the power dynamics of race and prestige (among researchers, among decision-makers, among what makes a “credible” messenger and to whom) enter communication. They also implemented more space for dialogue and co-learning across workshop participants. Curriculum leaders also facilitated conversations about the risks and potential harms of public engagement and communication about health equity, and began attending to specific ways to mitigate those harms. Finally, curriculum leaders began to explicitly center voices that have been historically excluded from academic research and communication practice in the trainings. While the basic structure of the curriculum stayed constant, the increased emphases on racism, power, and equity were necessary to meet teams’ needs.

Qualitative Thematic Analysis of Dissemination Plans

To illuminate specific examples of how community-engaged research teams approach dissemination planning, the authors conducted qualitative analysis of an anonymous cohort of teams’ initial drafts of their dissemination protocols (N=15 teams). One primary analyst reviewed all plans and identified categories and subcategories that emerged inductively from each of the domains identified in Table 1, using a reflexive thematic approach to the analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Then, a secondary analyst (JAL) examined a subsample of dissemination plans and cross-referenced the coding categories identified by the first analysis to expand our understanding of the categories. Of note, the primary analyst was very familiar with the program, but the secondary analyst was new and had no relationship with the teams or program prior to serving this role. The evaluation of these dissemination plans by the author team did not have a specific marker of success, and so the knowledge of the team served mainly to place the dissemination plans in context. Specific team names and identifiable details (such as geographic indicators, names of key audiences or specific policymakers, etc.) were removed, so that all results of the analysis are anonymous and not tied back to specific research teams or projects. The purpose of this de-identified analysis was to present exemplars of dissemination planning elements to inform the work of future research teams that may want to adapt the protocol presented here. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board determined this analysis to be exempt from human subjects review.

Results

As outlined in the template (Table 1), the first task of the planning protocol was to identify teams’ “dissemination goals,” or the changes they want to see result from their communication (in contrast to the research goal, which is more narrowly about research outcomes). Dissemination goals can span four types – awareness, engagement, advocacy, or action (such as a policy or practice change). All but one team included an awareness change goal, most commonly defined as a change in knowledge or understanding about the evidence surrounding some problem facing their community (Figure 1). Engagement goals, defined as bi- or multi-directional communication or collaboration among groups in the community around the issues of interest, were also common, described in 13 of 15 plans. Nine teams articulated an advocacy goal, defined as affecting the organized advocacy efforts of their team, partners, or other intermediary organizations. Action goals, defined as directly creating or influencing a policy change, were least common, described by eight teams. Five teams described having dissemination goals that covered all four dimensions; citing two or three goals was most common, and no teams described only a single goal category.

After articulating their dissemination goals, teams described the audiences they needed to reach to achieve their goals (Table 2). Reflecting the community-based nature of their projects, all teams described audiences within the communities where they were undertaking the research as primary, including participants and other residents. The teams also included healthcare system leaders, clinics, and legislative bodies among the primary audiences. Given that more than half of the teams had advocacy goals, many teams included advocacy organizations and non-profits among their primary research audiences.

Secondary audiences cited were more diverse, and encompassed many of the same types of community, practice, and policy actors and audiences as in the primary category (Table 2). Secondary audiences that did not appear as primary audiences for these research teams included academic disciplinary audiences, educational institutions, funders, and residents of communities beyond the research focus.

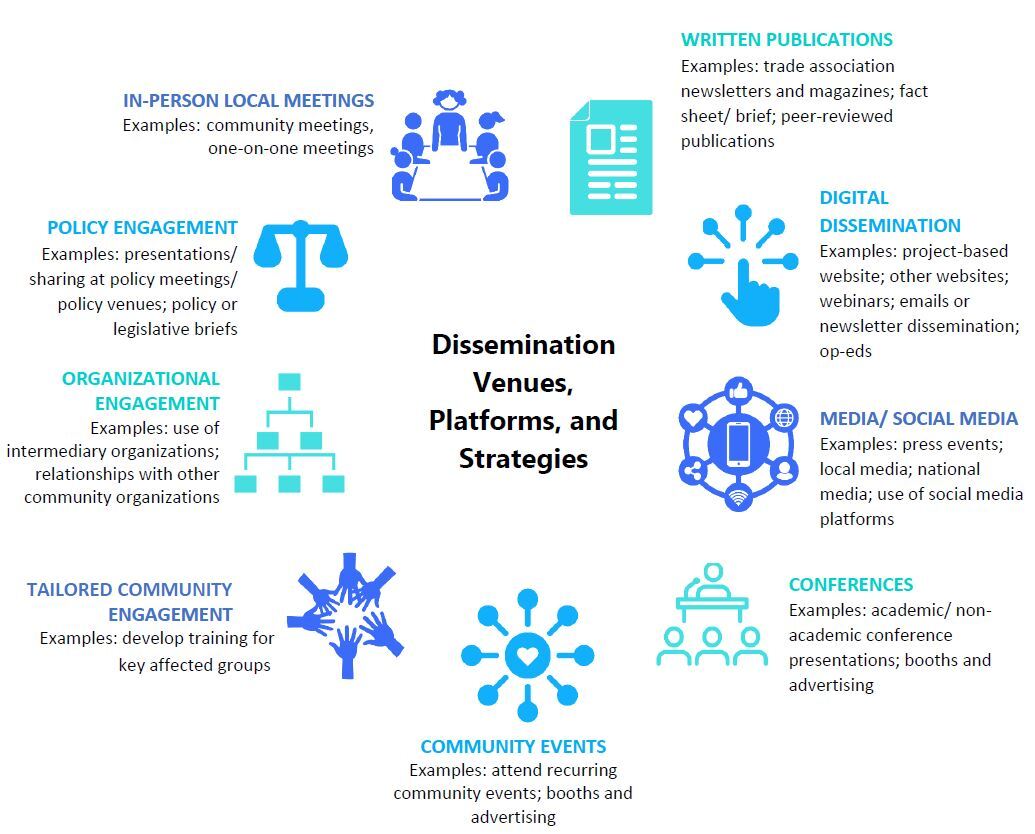

The bulk of the planning document addresses tactics the research teams proposed for reaching their audiences, and related timelines (Table 1). Reflecting key concepts of effective dissemination strategies from the curriculum (Ashcraft et al., 2020; Brownson et al., 2018), the vast majority of proposed mechanisms for dissemination were formats other than the academic journal article. An infographic displays the heterogeneity of formats that the research teams proposed (Figure 2). Many of the formats relied on building relationships with specific groups or individuals who are best poised to act on the results, including specific policymakers (e.g., those serving on relevant legislative committees) and specific members of organizations (e.g., advocacy organizations) who can leverage the research results for change. In each of the plans, teams proposed community events such as town halls or community meetings to share the results of their research back to community residents and/or research participants. Teams also proposed to leverage traditional media and social media, both to directly share research results (such as through op-eds or use of Twitter or blogs) or as intermediaries to share the research (such as through purposeful identification of journalists who commonly write on the “beat” related to the research focus). While teams often proposed written communications as formats for dissemination, peer-reviewed journal articles were only one type. They also proposed to develop fact sheets or research briefs as well as placing informational pieces in trade association publications to reach non-academic audiences for whom journal articles might be less accessible.

Finally, teams proposed a variety of ways to informally and formally track the success of these strategies (Table 3). Because the research teams’ grants were comparatively small (approximately $100,000), these metrics most often were low-cost ways of tracking impact, including recording the numbers of visits to websites, downloads, and automated tracking, such as through social media metrics or other existing mechanisms (e.g., Altmetrics). Teams also incorporated ideas for tracking the relational impact of their community research work, such as noting the numbers of email inquiries or participants at events. Reflecting their longer-term policy change goals, teams also identified metrics at the policy level, including bills and programs adopted or implemented.

Discussion

An intentionally designed dissemination planning curriculum supported community-engaged research teams to proactively consider their action goals early on in their research projects. A simple template supported teams to consider diverse audiences, formats, and tactics for translating their research, which dissemination science supports as critical to achieving authentic and timely impact from research (Brownson et al., 2013, 2018; Kwan et al., 2022). Teams were encouraged to consider dissemination as an ongoing process, as opposed to something that happens at the conclusion of the project, and they considered the larger body of knowledge they held on their issue as the content for sharing, not just specific research findings. Teams were largely successful in identifying awareness and engagement goals and primary audiences that flow from those goals in the community as well as policy and clinical settings. They had specific short-term actions in mind, not only a longer-term and/or abstract vision of how their research might benefit communities. Further, they identified multiple opportunities and formats to disseminate research results beyond conventional products, such as the academic journal article.

This curriculum has helped to mobilize cohorts of teams’ dissemination activities since the program launch in 2016, and the process of systematically analyzing one cohort’s plans revealed important opportunities for the future. First, there is a need to further document the impact of using proactive dissemination plans. Program evaluation data can be used to identify how often teams disseminated their work to the end-users they identified, in what manner and formats, and for what impact. One important contextual limitation of this particular analysis was that the plans analyzed herein were drafted before the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020. The 15 teams’ proposed activities had to be modified because of the public health circumstances when it came time to share results (e.g., proposed community meetings were shifted to virtual formats; some events, such as in schools, were cancelled). We are unable to evaluate how often these specific plans translated into actual dissemination activities, given the major disruptions the teams faced. However, evaluation of the impact of community-centered dissemination plans – particularly on advancement of advocacy and action-related goals – is critical. We recognize that such evaluation will need to be tied to dedicated funds, and research funders can support this work by requesting explicit discussion of both dissemination plans and evaluation-related budget justifications. Yet, typical public health funding is short-term, whereas the systems- and policy-related impacts that are critical for promoting health equity would only be realized in the longer term. Work is thus needed to identify how to measure incremental and intermediary outcomes, in addition to dedicated attention to evaluation of longer term change.

Another related challenge for those engaging in dissemination activities is that the published guidance for the range of interested parties highlighted in these results is limited. While there are useful resources created to guide researchers in their dissemination to policymaker and journalist audiences (see e.g., Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2019; Scholars Strategy Network, 2024), the field is only beginning to explore effective strategies for dissemination to diverse community, practice, and business audiences. Processes such as those proposed by Purtle and colleagues (2022) (including audience segmentation, message tailoring, framing, and identifying and utilizing power held by key influential actors) can be examined in terms of utility for diverse audiences (Purtle et al., 2022).

Third, reflection on the curriculum elements revealed some gaps in how well health equity goals and values were captured in the communication training and processes used. As noted above, the curriculum creators and facilitators adapted curricula over time to include more explicit attention to the dynamics of power, racism, and other drivers of structural inequities. While there has been some recent work considering and implementing anti-racist praxis in community-based participatory research (Alang et al., 2021) and in implementation science (Shelton et al., 2021), more research and theoretical development is needed to consider how dissemination as a specific set of processes and procedures can be anti-racist. There is little work, to our knowledge, on antiracism praxis in dissemination science (although see one recent exception in the field of psychology, Fuentes et al., 2022). Since research institutions tend to be white-dominant and dissemination is traditionally conceptualized as one-directional translation of research (with an implicit “deficit model”, implying that the lay or practice community is deficient in their lack of scientific evidence and communication will rectify this, see Seethaler et al., 2019), innovative thinking about how dissemination – the terms, processes, and praxis – can be modified to be antiracist is an important priority.

In conclusion, the protocol and processes from this curriculum can be applied to and used by other research teams in their efforts to consider dissemination proactively, and prompt explicit, early, attention to knowledge sharing for broad impacts. Following this type of process can support research teams’ accountability for dissemination to multiple audiences, can be used in a participatory way in collaboration with multiple types of interested parties (from research participants to local policymakers), and can help research teams consider the longer-term policy and practice changes that could result from their research.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the AcademyHealth research assistants that were involved in the implementation of the IRL dissemination curriculum (Paul Armstrong and Sarah Millender), the co-instructors of the curriculum elements described in this article (Lauren Adams of AcademyHealth and Ra’Shaun Nalls of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health), and all past and present IRL staff, Co-Directors, Associate Directors, and senior advisors. We also thank all the IRL fellows and alumni whose feedback has been critical for shaping the program experience.

Finally, we are grateful to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for their ongoing support for this program. Support for this article was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant #79830).

.png)

.png)