Introduction: Involving local stakeholders in qualitative data analysis

Participatory research strategies, wherein local stakeholders (alternatively referred to as community members, local collaborators or citizen researchers) collaborate with trained researchers, are applies to co-create, anchor, and validate knowledge within local communities or organizations. Rooted in a constructivist epistemology, these strategies view knowledge as a negotiated process and recognise groups with lived experiences of the researched topic as important participants in this negotiation. Consequently, they aim to incorporate local stakeholders’ perspectives throughout the research process (Best et al., 2021; Haijes & Thiel, 2016; Hartley & Benington, 2000; Pope, 2020). The levels of participation of local stakeholders can vary across the research process. Vaughn & Jacquez (2020) identify five levels of participation: information, consultation, involvement, collaboration, and empowerment. Information represents the lowest level of participation, while empowerment represents the highest. In this context, empowerment means that participants lead the research decision-making.

Local stakeholders are often reported to contribute to research design, data collection, discussion, and dissemination of results (Jackson, 2008). However, their contributions to data analysis are less frequent (Best et al., 2021; Cashman et al., 2008; Jackson, 2008; Kowe et al., 2021). When local stakeholders do participate in data analysis, they are primarily consulted at this stage (e.g., McElfish et al., 2016; Pope, 2020), but they rarely engage in the entire analytical process, which tends to be led by expert researchers (Jackson, 2008). As a result, local stakeholders are positioned at what Vaughn and Jacquez would describe as a lower level of participation. This limited involvement means that the potential benefits identified by Cashman et al. (2008) are not fully realized. According to Cashman et al. (ibid.), jointly interpreting data with local stakeholders can articulate and integrate differing perspectives, enrich insights and discoveries, increase the credibility of outcomes, and enhance the likelihood of their translation into practice.

Barriers and challenges

According to Cashman et al. (ibid.), one reason for not including local stakeholders more fully in data analysis is their lack of analytical skills. This can be mitigated through training, and where local stakeholders are included in analysis sessions, they are often trained to participate (Best et al., 2021; Clark et al., 2022; Jackson, 2008; James & Buffel, 2022). However, providing training workshops requires time and resources, and the same applies to conducting analysis with local stakeholders. For instance, Jackson (2008) reports several instances where a two-day analysis workshop was held with a gap of several weeks before the second day because participants’ other commitments made it impossible to schedule two consecutive days. Cashman et al. (2008) describe an analysis conducted over eight months due to participants’ other commitments. In addition to being lengthy, analytical processes with local stakeholders require intense facilitation by one or more individuals with prior analytical experience, knowledge of the process, and the ability to guide local stakeholders through the analysis by breaking it down into understandable and engaging steps (Cashman et al., 2008; Jackson, 2008). These barriers of time and resources are particularly relevant in short-term research projects and/or projects with limited funding.

Apart from the barriers mentioned above, at least two other challenges must be overcome when involving local stakeholders in data analysis, according to Jackson (2008). Firstly, large volumes of data can be overwhelming and difficult to manage, necessitating that data be presented in a more manageable format. Secondly, to encourage participation, it is essential to foster a positive and supportive atmosphere where all participants feel able to contribute equally to the discussion.

The identified barriers and challenges related to participatory qualitative analysis are listed in Table 1.

The method presented in this tutorial—a board game-inspired technique to engage local stakeholders in qualitative data analysis—aims to overcome these barriers and challenges.

This tutorial is structured to provide a comprehensive understanding of how a game for participatory qualitative analysis can be designed, what elements it can consist of, and how the process of preparing, playing, and analysing the results of the game can be structured. The tutorial concludes with a discussion of how the game addresses the barriers and challenges that have been identified in the literature.

Framing the analysis as a board game

Adams defines a game as “a type of play activity, conducted in the context of a pretended reality, in which the participant(s) try to achieve at least one arbitrary, nontrivial goal by acting in accordance with rules” (Adams, 2010, p. 3).

The rationale behind framing the participatory analysis process as a game is to leverage participants’ familiarity with one domain – gameplay – to support their engagement in an unfamiliar activity (Jensen & Jensen, 2011), qualitative analysis. Furthermore, the playful nature of games enhances participation, as games are commonly associated with leisure, fun, and entertainment (ibid). Presenting an activity as a board game evokes these associations of playfulness and ease, which is particularly advantageous when the activity is complex, as with qualitative data analysis.

Lieberoth (2014) recounts an experiment in which an activity was presented in three ways to three groups of participants: as a survey, as a simple or rudimentary game, and as a complex game with an elaborate board, a prize, etc. He detected no significant difference between the simple and complex games’ ability to engage participants. This led him to conclude that as long as something is presented and accepted as a game by participants, the positive qualities of games are activated. To ensure that an activity is accepted as a game, a number of game elements should be incorporated. These could include a board, playing pieces, rules of play, dices, cards, turn-taking, tasks, roles, rewards, etc.

Designing the Participatory Qualitative Analysis Game

With Lieberoth’s point in mind, a relatively simple game was designed. The Participatory Qualitative Analysis (PQA) Game incorporates the following elements: a board, cards, game prompts, penalty cards, rules of play, turn-taking, and tasks. Among these elements, (a) the board, (b) cards, (c) game prompts, and (d) penalty cards constitute tactile game elements or objects, which will be described below. The non-tactile game elements will be described in the subsequent sections.

Tactile game elements

a. Board. A tabletop serves as a game board. For the PQA Game, three tables/boards are required to allow three rounds of play, the rationale for which is explained below (h). Each round will take place on a fresh board.

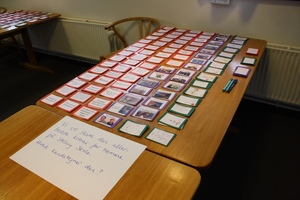

b. Cards. On each board, a set of cards is placed, requiring three identical sets of cards. Each set consists of 80 to 100 cards that are manually fabricated each time the game is used in a new context, as the cards are context-specific. Each card contains a small snippet of the data material to be analysed: a keyword, a short quote, or an image representing a concept or keyword (see Figure 1).

A set of cards represents a condensed and roughly categorized version of the dataset to be analysed. The cards serve to make the data manageable and accessible to individuals who are not trained in qualitative research (Jackson, 2008). At the same time, the cards act as “game pieces and props creating a common ground that everybody can relate to and at the same time they act as ‘things-to-think-with’” (Brandt & Messeter, 2004, p. 129), being rich enough in content to be read and interpreted in different ways by the participants.

A handful of blank cards and pens are also placed on the board in case participants wish to add something to the dataset.

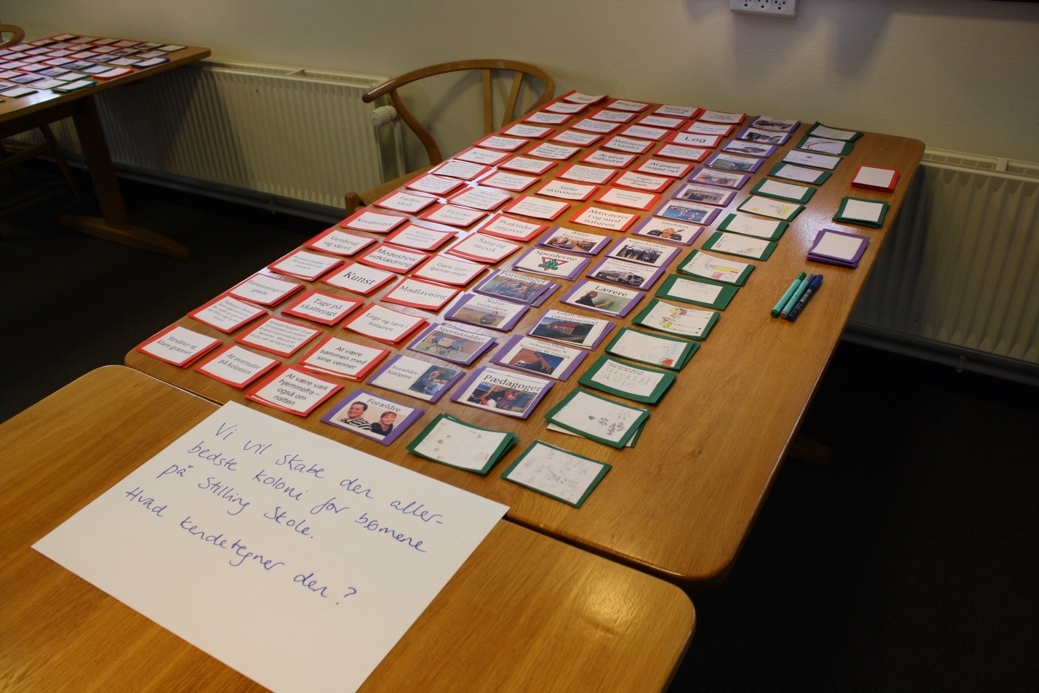

c. Game prompts. Three distinct game prompts are placed on the three boards, one prompt per board. Like the cards, the game prompts are context-specific, and their wording depends on the aim of the analysis. The game prompts are phrased as questions, and players choose and place cards on a “blank” part of the board to answer the question. The questions typically represent different perspectives on the research topic. For instance, in a game about new mothers’ and nurses’ views on maternity leave, especially vulnerable aspects of maternity leave, the questions asked what should be focused on to improve the experience of maternity leave according to the perspectives of mothers, nurses, and families, respectively.

d. Penalty cards. In some versions of the PQA Game, penalty cards have been used. These are simply sticky notes in a vibrant colour that those participants who receive them can place on their clothes. Penalty cards are stored on the boards. Penalty cards serve to keep the discussion flowing by visualising that certain statements, which could slow down or halt the discussion, are banned. The game responsible decides which statements should trigger a penalty card. In some versions of the PQA Game, these have included statements such as “this will never work,” “we have tried this before,” and “this is too expensive” (see Figure 2).

The combination of the tactile elements (penalty cards excluded) can be seen in Figure 3.

Non-tactile game elements

Non-tactile elements in the PQA Game include (e) rules, (f) roles, (g) turn-taking, and (h) rounds.

e. Rules. A set of rules instructs the participants on how to play the game by explaining what tasks they need to carry out and in what order to achieve the game’s goal. As stated by Brandt & Messeter, “rules set the boundaries for what is possible and structure the play of the game” (Brandt & Messeter, 2004, p. 122). The rules of the PQA Game are presented in a short introductory talk by a person responsible for the game before commencing gameplay, and a set of rules is placed on each board in case the participants need to consult them. Following Lieberoth (2014), they are explicitly named “Rules of play” to signal to the participants that this is a game and to stimulate a sense of playfulness. The rules are shown in Figure 4.

f. Roles. In board games, participants commonly assume roles that overwrite their everyday roles and identities, such as job roles. In the PQA Game, all participants take on the same role: that of a player. The reason for having a single uniform role rather than differentiated roles is to achieve a levelling and equalising effect, making it easier for participants to set aside everyday power relations while playing (Brandt & Messeter, 2004, p. 130). Additionally, a game responsible acts as a gamemaster while the it is being played.

g. Turn-taking. As specified by the rules, participants take turns choosing cards to answer the game prompt, placing the cards on the blank part of the board while explaining why they were chosen and relating them to the cards chosen by other players. Turn-taking is used to create an inclusive atmosphere and promote equal participation. By taking turns, all participants are heard, and no one monopolizes the discussion.

h. Rounds. The PQA Game is played in three rounds. Playing three rounds allow participants to

-

explore the data from different perspectives provided by the game prompts.

-

obtain a sense of mastery of the game. The first round is longer (45 minutes) than the two subsequent rounds (20 minutes each) in order to give participants time to familiarise themselves with the data cards. As the same data cards are repeated on the next tables, the need for familiarisation diminishes in the two last rounds.

-

have a dynamic experience, where the pace of the game helps keep engagement high.

Using the Participatory Qualitative Analysis Game

The entire process from preparing the game to processing the results is described below. The process can be divided into three steps: 1. preparing the game, 2. playing the game, and 3. processing the results.

Step 1: Preparing the game

In the first step, the data material for analysis in the PQA Game is pre-organized by the game responsible or another designated individual to enhance accessibility and manageability for participants. This involves condensing and sorting the data into 4-5 broad categories. Condensing and sorting are established analytical activities commonly employed in qualitative research (e.g., Kvale & Brinkmann, 2015; Miles & Huberman, 1994). Therefore, the preparation of data material for the PQA Game can be viewed as an initial stage of data analysis—a type of pre-analysis.

The specific categories created vary depending on the data material; however, common categories include people/actors/agents, places/locations/settings, activities, objects, and emotions. These broad categories, resembling the primary coding domains proposed by Tracy (2019, p. 214), are intended to structure the data, giving participants a clear overview during gameplay. To maintain an appropriate level of complexity, the number of categories is limited to five.

After condensing and categorizing the data, between 80 and 100 keywords, sentences, statements, or citations are selected to represent the data material. As can be seen on Figure 1 and Figure 3, some keywords are supplemented with or replaced by pictorial representations to make the content instantly decodable. For example, a keyword like “people standing in a queue” could be accompanied by an image of people queuing, and the name of a well-known brand could be replaced by the brand’s logo.

Given the subjective choices involved, it may be useful to reflect on how decisions made while creating the cards shape their interpretive potential. The person creating the game might acknowledge that the cards and their content reflect their own analytical choices and consider how their positionality and assumptions could influence this process. Pictorial representations, in particular, benefit from thoughtful use, as they may introduce biases into the data cards. Images depicting groups of people can unintentionally emphasize certain demographics.

The selected keywords are printed and affixed to cardboard cards, each coloured according to category. The next step is to develop the game’s three prompts in collaboration with central stakeholders. If the game has been commissioned by an NGO or a municipality, these stakeholders may include project managers, chairpersons, managerial staff, and/or internal consultants. As noted earlier, the game prompts are closely tied to the aim of the analysis and its research question(s), and are designed to elicit different perspectives on the data material.

Lastly, the game-playing workshop must be organized, participants invited, and the room set up. Altogether, the preparation of the game is estimated to require the equivalent of about three days of work for a person skilled at handling qualitative data and organising workshops.

Step 2: Playing the game

The second step involves participants playing the game. Before they begin, the game responsible introduce participants to the rules and ask them to engage with the data cards to answer the game prompts’ questions. As previously described, participants answer by selecting and organising data cards on the boards. They are encouraged to add new cards or modify existing ones by writing directly on them as needed, incorporating their own experiences, beliefs, or ideas. In this way, participants actively contribute to the data throughout the game, expanding, adjusting, clarifying, and refining it. Any handwritten additions are easily identifiable on the printed cards, allowing for a clear distinction between the initial data and the enhanced layers of data and interpretations added by participants. New cards typically expand the data material, while modified cards are results of analytical activity.

Participants take turns selecting cards to respond to the game prompts, placing them on the blank section of the board while explaining their choices and connecting them to cards chosen by other players. Some groups arrange the cards relatively randomly, while others carefully place them in specific patterns (Figure 5). Likewise, some players pay attention to the card colours, which reflect initial card categories, while others ignore this detail. To encourage open interpretation, and in keeping with a constructivist epistemology, participants are not required to consider the initial categories.

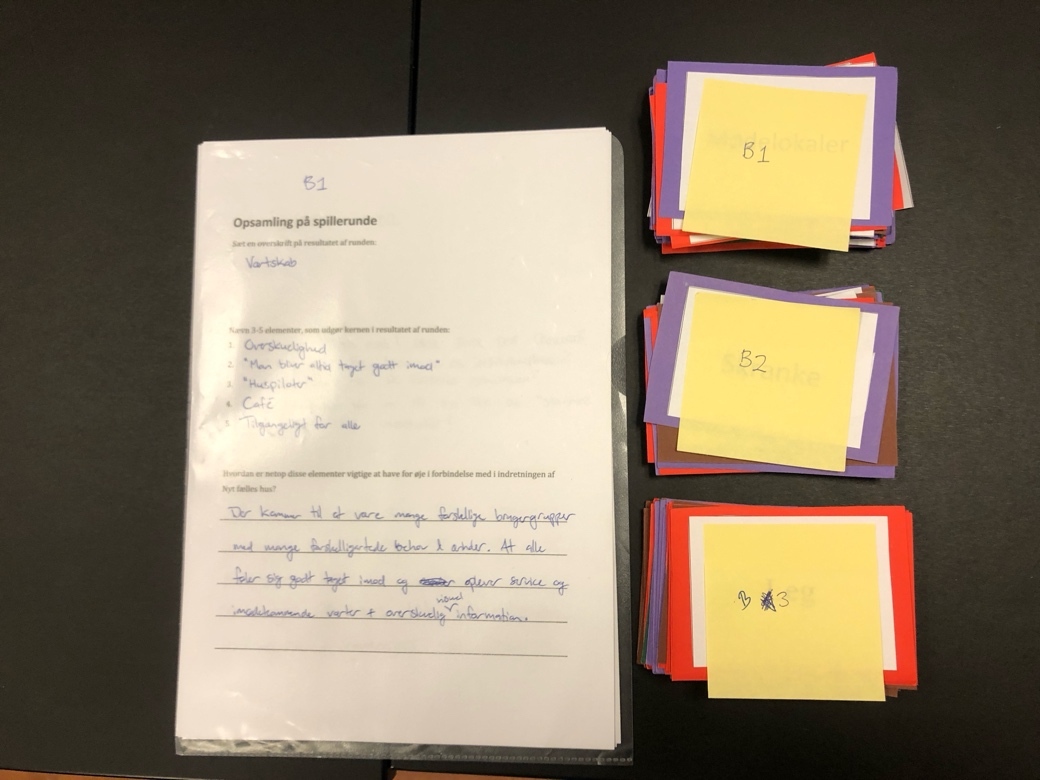

After three rounds of playing, which may have been punctuated by a snack or coffee break, participants are divided into three smaller groups or pairs. Each group is asked to create a summary of one of the rounds. To help support this activity, they are given a summary sheet with predefined categories to fill in. They complete the summary sheet by giving the result of the round a headline, assigning keywords to the result, and writing a short description.

The game is now over, and the participants and game responsible sit down together for a 15-30-minute debriefing session. During this time, participants have the opportunity to share their experiences of the game. The purpose of this debriefing is to allow the game responsible to learn from the game session and detect any needs for fine-tuning or developing game elements in a future session.

Once the debriefing has ended, the participants leave the location. The game responsible then documents the game by photographing the results of the rounds played, collecting the summaries and cards that were chosen, and noting in which round the cards were chosen and which particular round each summary covers (Figure 6). The collected material will be used in step 3.

Step 3: Processing the results of the game

The game responsible (or another designated person) conducts a post-analysis of the selected cards. The nature of this analysis depends on the purpose and desired outcome of the analysis.

In some cases, it may be useful to sort all the selected cards across rounds to see which cards were chosen most frequently and what this might mean in relation to the overall research question. This was done in the previously mentioned version of the game exploring views on maternity leave. The selected cards were pooled together and sorted into piles of identical cards, which were then organized into a narrative—the narrative that could be constructed from the participants’ card selections.

In other cases, the selected cards may be treated as a dataset in their own right, and categorised into new, inductive categories. They are new in the sense that they differ from the broad categories created in step 1, and inductive because they emerge from the cards themselves, rather than from theoretical concepts or models. These new categories can then be analysed to provide an answer to one or more research questions, much like in a more conventional thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This approach is particularly relevant when the same version of the PQA game has been played by more than one group, resulting in a considerable number of selected cards, and/or when participants have modified and added several cards. The new and modified cards may warrant extra attention, as they contain participants’ own words and serve as the most direct indicators of their perspectives.

If there is particular interest in exploring the process of negotiating knowledge during the game, the interactions between participants in Step 2 could be recorded. These recordings could then be used to trace and analyse this process in detail, supported by an analysis of the selected cards and any modifications made to them.

Other approaches are possible as well. It should be stressed that the abovementioned approaches are just a few examples of how a post-analysis may be carried out. Similarly, the analysis can be reported as seen fit. The amount of time needed for step 3 depends on the complexity of the post-analysis and the report.

Conclusion and discussion

The PQA Game has been used in community-based participatory development projects in both the public and civil sectors. Specifically, it has been applied with employees and parents in a public school, residents of different ages in a village, stakeholders in an association, and citizens as well as public servants in various municipalities. Based on these experiences, the game will be discussed in relation to the barriers and challenges associated with participatory qualitative analysis mentioned in the introduction and summarized in Table 1.

-

Local stakeholders need training to participate in qualitative data analysis.

No training is needed to participate in the PQA Game. Participants have been able to play the game immediately after being introduced to the game and its rules. A game responsible has been available throughout the entire game, and his or her guidance has typically been requested in the initial part of the first round. However, soon after, the game responsible’s assistance has no longer been needed.

-

Local stakeholders’ other commitments make it difficult for them to find time for lengthy analysis processes.

The PQA Game takes between two and three hours to play (introduction 20 minutes, first round 45 minutes, second round 20 minutes, third round 20 minutes, debriefing 15-30 minutes), breaks excluded, and is played during one workshop. This relatively short timeframe may make the workshop easier to fit into participants’ schedules compared to the analysis sessions described in the literature.

-

The analysis process requires facilitation by someone who deeply understands the process and can guide local stakeholders through it.

As mentioned in point 1, the PQA Game requires little direct facilitation. This does not mean there is no need for someone who understands the process. This person has a heavy workload during the preparation phase, described above under “Step 1: Preparing the game.” The most time-consuming tasks in this phase are sorting and condensing the data and producing the data cards. It is possible that generative AI (LLMs) can assist with sorting and condensing the data material, which would make this task less demanding in terms of human resources. However, generative AI cannot help with cutting out data cards and gluing them together. The human resources available for this task limit the number of groups that can be involved in a game, as up to 300 cards are needed per group.

-

Making data manageable to avoid overwhelming local stakeholders.

The cards of the PQA Game serve to make the data manageable for participants. While the number of cards can initially overwhelm participants, this feeling is quickly overcome. By the second round of playing, participants show familiarity with the cards.

-

Ensuring a positive and inclusive atmosphere for participation, where all participants are heard.

Framing the analytical process as a game seems to evoke positive associations that contribute to a constructive atmosphere. Additionally, the game responsible plays a significant role in setting the tone and mood for the game session.

The PQA Game has proved suitable for diverse or mixed groups, including participants from different age groups, citizens and public employees, staff, and management. It appears to have the desired inclusive and equalizing effect, supported by the game’s rules and turn-taking. An important aspect of ensuring equal participation is group size. Like Jackson (2008), we have found that small group sizes work best. With 5-6 persons per group, rounds do not take too long, and everyone has the opportunity to speak frequently.

So far, the game has only been used in a Danish context. Danish culture is characterized by extremely low power distance (Hofstede, 1983), and equality is highly valued. In cultures with higher power distance, extra measures may be needed to ensure equal participation. Even in a Danish context, participants’ social relationships with each other affect the playing of the game. Participants have been observed to be more reluctant to hand out penalty cards in groups that do not know each other in advance, possibly because they are unsure of how the penalised party will react. In groups where participants are well-acquainted, penalty cards have been used humorously.

To sum up, presenting the analytical activity as a game creates a playful space where everyday constraints, priorities and power relations are to some extent put aside, and where participants feel capable at and at ease with handling qualitative data within a short timeframe. The PQA Game can potentially be used in a multitude of settings where there is a wish to engage local stakeholders in qualitative data analysis. While the game requires little time and no existing qualitative research skills from participants, the game responsible and/or his or her collaborators should expect to invest several days of work in the preparation phase and in processing the results.