Introduction

Completing a Ph.D. is a rite of passage that allows (but does not guarantee) entry into academia. It is assumed that by dedicating years of study to a particular topic, that depth of understanding and insight brings license to teach students about that topic, to continue researching, and to complete service in support of the institution and the broader field. Although plenty has been written about how the depth of topical understanding does not automatically translate into pedagogical effectiveness (Bullin, 2018; Gale & Golde, 2004; A. Jones, 2008) there is less written about how Ph.D. graduates adapt to managing large-scale research.

As scholars continue in their academic journeys, many travel from a solo-authored study, often unfunded, to funded research involving research partners, co-authors, collaborators, and other partners. In Canada, our major national funding agencies describe this in explicit terms. For example, the Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) funding model emphasizes interagency collaboration, joint initiatives, and deepening partnerships. The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) encourages Canadian companies to participate and invest in research. The front page of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) website states that they “collaborate with partners and researchers” (CIHR, 2024). These agencies prioritize collaborative, partnered research. Attaining research funds from these agencies is highly competitive and considered high stakes, as they inform university rankings, leading to pressure to grow and expand research initiatives, resulting in more dollars, more partners, and higher rankings (Bélanger & Lacroix, 1986; Ebadi & Schiffauerova, 2015; Gauthier, 2004; Hazelkorn & Gibson, 2017). Yet little has been written about the transition from conducting solo, unfunded Ph.D. research to large-scale funded research. In this article, I am defining large-scale (multiple collaborators, partners, or funders) research partnership facilitation within the context of collaborative community-based participatory research, where fostering relationships is of key importance.

Through an autoethnographic study examining my own experiences of making this transition, I describe leadership lessons learned from large-scale community-based research partnership facilitation, offering insights for other scholars moving from individual to partnered research, or from small studies to more complex ones. By using my own experiences of leading a large-scale research project as data, I critically examine the larger context of research trajectories. I use the metaphors of conducting an improvisational music group and of a cobbler fitting shoes for others as ways to illustrate the leadership lessons described within this article. This study also informs institutions looking to support new and emerging researchers in this transition. Specifically, faculty career development can be supported by recognizing the gaps in skills and tailoring professional development in response. This article identifies specific areas of needed expertise, providing institutions with knowledge of what gaps exist for scholars aiming to grow in their research.

Literature Review and Research Context

In order to understand the broader context surrounding my own experiences, and to understand whether my experiences were unique or were common to other academics, I conducted a literature review aimed at answering the following questions in relation to transitioning from solo doctoral research to large-scale research partnership facilitation: How are Ph.D. students currently trained for things like project management, budget management, and other logistical and human aspects of research facilitation? What happens when researchers move from one or two funders or partners to a complex network of invested individuals, partners, and organizations? And finally, why might belonging matter in relation to this issue, and what might it look like to foster it within such a complex web of relationships?

Management Training

Project management is a field of its own, and although completing a Ph.D. involves elements of project management, it does not often include explicit instruction in this area. In a multinational comparative study of doctoral student research, Katz (2016) found that the majority of Ph.D. students did not receive any training in the management of their research project. This was further confirmed by Jones (2017) who surveyed research students in the U.K. and found that only 33% felt that their training in generic or transferrable skills was covered by their degree. However, it is not only the project management skills that are lacking. Leadership skills are also needed. Although multiple years are spent to develop competent and successful researchers, leadership training can be completely absent. For example, Baas et al. (2020) wrote: “In order to become successful scientists, individuals must develop into leaders who are able to relate to and understand others and, in addition, manage and understand themselves” (p. 87, italics mine). This lack of training in the skills and abilities required to lead larger groups and manage projects becomes compounded as research projects increase in complexity. In writing about taking over a research group, Siegerink (2016) writes:

“The first role I distinguished was that of a researcher. This was the familiar role of someone who generates data, performs analyses and turns those findings into articles; the role I knew as a Ph.D. student and post-doc. My new roles included project initiator, project manager, mentor, methodological consultant, HR manager, accountant and, finally, team leader. All these roles have different implications and responsibilities, are sometimes not clearly discernable from each other, and have different priorities… Understanding the existence of these multiple roles, and learning to apply and combine them, has, to date, proven to be one of my most difficult challenges.” (p. 2340)

In smaller institutions, these roles may be even more complex, as institutions may not have the organizational capacity to offer things like grant-writing support, small operational grants, access to doctoral students, access to large databases, and so on (Murray et al., 2016; Wayne et al., 2008). Not only do these disparities result in what Murray et al., (2008) call the “dire consequences” (p. 1) of fewer successful grants, even if successful, they can result in the principal investigator taking on additional roles and responsibilities, adding further complexity to the role (Decker et al., 2016). Lack of support for principal investigators conducting publicly funded research was a key finding of Cunningham et al., (2012) who wrote: “We found that PIs were frustrated by the organizational constraints of their institutions and the experience of the support they received was not ‘helpful’ and was ‘compliance’ based” (p. 102). However, all of the PIs they interviewed were in institutions which had centralized administration services like finance, human resources, and technology transfer. In contrast to the legitimate constraints described by Cunningham et al., (2012), in smaller institutions the lack of infrastructure and support does not lead to more research freedom, but instead to more demands on the principal investigator:

Overall, the survey results illustrated that faculty in small to medium programs are caught in a vicious cycle that makes it challenging to become successful in research. Lack of resources leads to a lack of research production. Lack of research production unfortunately leads to a lack of opportunities in research, such as grants or other types of funding and big collaborations. Without funding and collaborations, overwhelming clinical duties, lack of infrastructure, and protected time, researchers are trapped and the cycle continues. (Decker et al., 2016, p. 45)

It is critical that institutions consider how to support faculty members aiming to grow their research agendas and that this development includes management and leadership training. It is also important that professional development or training fit the context of the institution. For example, in smaller institutions principal investigators may need support in grant writing, time management, facilitating collaborations, or other infrastructure gaps, whereas faculty in larger institutions may need support in navigating the systems which exist within their institutions.

Increasingly Complex Projects

In addition to the lack of training for these multiple roles, researchers also struggle to balance the conflicting needs that come with more complex projects. Lechelt et al. (2019) describe pressure to cooperate with industry and civil society, as doing so brings more funding and mobilizes research knowledge beyond the university. But this broadening of funders, invested research partners, collaborators, and other parties requires increased negotiation, which they call “understanding the opportunities and challenges in different types of relations we might form” (p. 4). These relationships require the researcher to have an understanding of relationship formation and maintenance and to do this work in an increasingly complex web of relationships.

The web of relationships is not only larger in larger-scale research, but it is also more varied. Tensions between the needs of community partners and the demands of academia have been well documented, including differences in roles, expectations, priorities, processes, timelines, and desired outcomes (Lam & Mayuom, 2022; Ogunsanya & Govender, 2019; Sieber, 2008; Stahl & Shdaimah, 2008). These differences can be sources of conflict, and they also require increased time and effort on the part of the principal investigator in (at best) proactively negotiating and (at worst) managing conflict. For example, industry partners may have readily available funding but be focused on market-ready research, involving careful negotiations around intellectual property and ownership. Community organizations may operate with limited resources or may have funding parameters that define who can participate in the research. They may have different understandings of ethical processes. They may have expectations about what can be done with the knowledge produced, and who it will benefit. As research projects broaden and become more complex, the role of the principal investigator includes that of negotiator, liaison, and occasionally, diplomat (Boehm & Hogan, 2014). Combined with the need for increased training in management and leadership skills, skills in maintaining respectful relationships across multiple areas of difference (industry partners, funders, community partners, academic institutions, co-researchers, participants, etc.) are also needed.

Fostering Belonging

As described above, as projects become more complex, cooperation at multiple levels becomes increasingly necessary. In addition to managing project logistics and conflicting project partner needs, the leader must also ensure that the complex web of involved individuals remains connected to and invested in the research. This cooperation can be fostered or hindered by individuals’ sense of belonging to the group (De Cremer & Leonardelli, 2003).

Belonging involves “sharing values, relations and practices” (Anthias, 2006, p. 21) and is a way of signifying social location that carries an emotional attachment. It is possible to have a sense of belonging within a large group, but it is something that must be purposefully constructed, and particularly so when the group does not naturally have intragroup similarities (Easterbrook & Vignoles, 2013). Although socially similar groups may find a sense of congruence quickly, they may not function well due to limited perspectives or shifting identities in light of new knowledge and experiences (Hughes, 2010). Relationality and social support play a large role in predicting whether group members will feel a sense of belonging (Dluhy et al., 2019; Krause, 2016), however, maintaining deep relationships can be difficult with large numbers. Individuals find it easier to establish trust in smaller groups (La Macchia et al., 2016) and individuals also prefer working in smaller groups (Soboroff et al., 2020). There may also be pushback from group members who prefer smaller sized groups, and want the closeness, intimacy, and leadership accessibility that comes in small groups (Keller, 2024). I appreciate Pfaff-Czarnecka’s (2011) definition of belonging, which points out that it involves both “collective boundedness, but also to personal options of individualisation and to the challenges while navigating between multiple constellations of collective boundedness” (p. 199).

Leading large community-based research effectively, then, is not only managing the logistics of project management, group leadership, and partnership negotiations, but it is also attending to the varying needs of the people involved in the project with an aim of fostering a sense of belonging and connection to the project. Faced with the lack of explicit training in these areas, how do researchers transition from single study Ph.D. research to large-scale research partnership? This study provides one example, with implications for individual researchers and institutions looking to support the transition. By using my own personal experiences as data, this article critically examines larger narratives and discourses in which my experiences are embedded, highlighting the need for context-specific professional development, training, and support.

Context

Within my institution, I am a tenured faculty member and director of a research centre. When examining my own belonging, there are areas of belonging which are institutionally regulated: I belong to the Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy, and to the Faculty of Education, and to my research centre. However, there are other sites of belonging which are complicated by a mix of professional roles, personal relationships, and affective dimensions of belonging.

This article draws from a study which involved the establishment of multiple rural research locations across the province. These locations were then digitally connected to a community-based participatory research project in which we were consulting rural citizens about their experiences with polarization and depolarization. The project involved the creation of the aforementioned research hubs, 20 research partners, and multiple partnering organizations.

Within the context of that study, I have colleagues and co-researchers with whom I work on this and other projects, individuals who are connected to the research centre but not to every project, students, community partners with whom I have previous relationships, other community partners who are new, and individuals in those organizations who are new to the organization. So, just as belonging does not remain static (Anthias, 2008), so also my belonging within the context of this study shifts and changes.

Methods

Autoethnography uses personal experiences to critically examine larger narratives and discourses in which my experiences are embedded (Wall, 2006). Put another way, it “uses myself to get to culture” (Pelias, 2003, p. 372). In this study, I examine my own experiences of making the transition from managing fairly small projects with a limited number of partners to managing a large project involving multiple locations with 10 rural digitally-connected research hubs, 20 research partners, and multiple partnering organizations. By examining my own experiences, I am able to more fully understand the larger context of institutional and partnered research priorities, individual scholarly research trajectories and transitions, and sense of belonging in academia.

This study revisited 185 pages of personal journal entries and notes, self-authored over the course over 2 years, from February, 2022, to April, 2024, to explore the following questions: 1) What are the lessons learned through the design and facilitation of a large-scale research project involving the creation of a connected network of rural research hubs? And 2) How do these lessons impact my identity as a scholar and director of a research centre? At the initial level of analysis, I read these journal entries and notes and selected everything related to the research project described in this article. I then began to organize those notes into early themes (Braun & Clarke, 2021), seeing where they might align or depart with the literature. I did this by starting a blank word document and jotting down what I thought of as the meaning of patterns I was seeing in my journal. For example, if I noticed a pattern of worrying about what my co-researchers might be thinking, I started writing those down in a new section of the word document. As I entered more and more into the document, I started grouping them and created headings that could explain the relationships between the patterns. In Braun and Clarke’s terms, the meaning of my patterns are called themes, and the headings of my themed sections are “overarching themes” (Braun & Clarke, 2021, p. 87). The wording of the headings changed over time and as I entered more into the document. So in the example above, what started out as “Managing Relationships” eventually became “Relationality, Roles, and Fostering Belonging.” As more data was entered into the document, the headings became more accurate and clearly organized around a central concept. At times, I moved content from one heading to another so that the concepts fit together in better (more clearly organized) ways. For example, I tried clustering the themes in a chronological flow of the research project, where the themes would follow the trajectory of the project. However, that quickly fell apart since many of the overarching themes (relationality) were found throughout. Still, as much as possible I tried to order the overarching themes in a way that would help the reader understand. So for example, I chose to put ‘belonging, grief, and acceptance’ towards the end, as most of this meta-thinking about my role and the emotional journey of this project was only in retrospect. In the same document, I also began a chart to help visualize the many different people and organizations involved in this project (Table 1), and the different tasks I was spending time on (Table 2). As I worked through my notes, I added to these charts. For Table 2, I moved the tasks into groupings based on the areas of leadership that were needed for each. Like the process of selecting themes described above, I also sorted and re-sorted the tasks until they were clustered under distinct areas of leadership.

By applying the concept of belonging (Pfaff-Czarnecka, 2011) to the research questions and my journal entries and notes, I examine my own sense of belonging, as well as my experiences of group dynamics and leadership within the large project team. Autoethnography can be difficult to manage in this type of project, because members of the research team know each other, and so confidentiality can be difficult to ensure. This is why I have kept the focus on my own experiences and my interpretations of them, rather than including specific quotations which would identify others. By reflecting on my experiences and critically examining the decisions I made along the way, I offer ways of understanding the struggles and successes of learning to lead large-scale research projects. This may be comforting to others in similar situations (Broeckerhoff & Magalhães Lopes, 2020), and it may offer institutions, particularly those of small size, ideas about what supports are necessary for growing researchers (Hernández et al., 2010).

Analysis

My notes and journal entries describe shifting roles, relationships, and the affective dimensions of care. I describe struggles with project management, paying extraordinary amounts of attention to the logistics of facilitation that vastly outpaced the attention paid to deep theorizing or exploration of the literature. I learned and navigated multiple institutional processes and policies, both written and unwritten, to address concerns of time management, to facilitate student involvement, and to find sources of support and development for myself and others. Ultimately, I came to understand my own role and belonging within a larger research constellation of relationships, and found ways to facilitate a sense of belonging for others.

Relationality, Roles, and Fostering Belonging

The concept that belonging is something which can be intentionally fostered is taken up by Kuurne and Vieno, who write that "belonging work is essentially relational work that does not reside in a person or within social entities but is located in relationships and targeted at shaping these relationships and their practices" (Kuurne & Vieno, 2022, p. 285). My notes and journal entries show immense concern for the co-researchers and students involved in the project. For example, I would routinely postpone administrative tasks (credit card charge-outs, for example) in favour of meeting the immediate needs of research assistants or research partners. Research centre-related duties were also postponed, such as podcast releases, website updates or monthly newsletters. For example, a co-authored chapter with other members of the research team was scheduled and written in short order, whereas a solo-authored article needing to be revised after submission to a journal was postponed multiple times, even though the revisions were not substantial. However, perhaps this ‘others-first’ rule went too far, as I also tended to prioritize collaborative initiatives over my own writing or research interests. The phenomenon of postponing important things for the sake of the urgent is described by Hummel (2013) as the “tyranny of the urgent” (p. 1). People within my immediate orbit (co-researchers, students, and key project partners) took precedence over the needs of people who read the research centre’s website or newsletters. There are also indications in my notes that I sometimes felt more comfortable to reschedule colleagues whom I consider friends over those colleagues or partners who felt more distant or with whom I was less familiar. Kim Marshall (2003), a former school principal, observed this phenomenon in his school leadership, as he wanted to be an instructional leader but instead found himself experiencing “hyperactive superficial principal syndrome” (p. 701), which prevented him from exploring topics of substance with his teachers. Many other scholars have addressed this phenomenon, cautioning against focusing on the immediate without requisite emphasis on the future (De Lissovoy, 2008; Restas, 2016), and with practical suggestions for time management such as shorter check-ins, pre-set rhythms and development of routines, grouping personal check-ins with other routine tasks, and using the "nooks and crannies of each day (Marshall, 2013, p. 704). If belonging is process-oriented (Kuurne & Vieno, 2022), and not automatically attributed due to group categorizations, then it becomes important to consider the “little gestures, behavioural patterns, social interactions, and engagement” (Kuurne & Vieno, 2022, p. 292) that constitute the work of belonging. This does not always fit nicely into typical time management advice, as human beings are not always predictable, scheduleable, or consistent.

The co-researchers on the project were mostly comprised of colleagues at my institution, although as the project progressed this changed slightly. When starting the project, I sent invitations to the whole faculty in my monthly research centre reports. However, all of the 5 co-researchers on the project joined because of a personal conversation with me, and not as a result of the wide invitation I sent to the whole faculty. I believe that this strength of establishing personal connections allowed for increased involvement in research, as people saw themselves as welcomed, able to be part of the team, and able to contribute. This is consistent with the literature, which shows that feeling connected increases perceived effectiveness (Cojuharenco et al., 2016) and that affirming social worth improves team contributions (Cunningham et al., 2021). It also strengthened the research itself, as a diverse team allowed for different backgrounds and areas of strength to be expressed. For example, one colleague taught me a better way of conducting safety protocols at the beginning of a focus group. Another made connections to other organizations interested in participating in the project. Another brought useful training for research assistants around coding data. Theories of belonging differentiate between in-group belonging predicated on sameness and the need for belonging to value and respect distinct identities (Davis et al., 2022). Our research group held elements of both: we had similarities based on our identities as researchers and members of a postsecondary institution, and based on our interest in rural communities, but we also had many differences in our positionalities, lived experiences, epistemologies, and worldviews. Fostering belonging, then, required working together for a common goal while honouring and respecting the distinctiveness that each brought to the team. However, theories of belonging stretch beyond bifurcated notions of group belonging vs. individual diversity. Rather, they point out that belonging is a complex, translocational, shifting notion that is not fixed, but is in process (Anthias, 2008). Therefore, attentiveness to ongoing relationality, roles, and shifting senses of belonging is critical for effective community-based research facilitation.

Managing External Relationships

Early in the project, I met with the superintendents from 9 different school divisions to both gain their input about the specific project and to strengthen connections for the research centre. However, maintaining the relationships between the centre and project partners is something that became more difficult as the project grew. For example, despite one or two emails providing updates to these external partners, and invitations to share recruitment information, they were not regularly involved or updated. For example, one organizational CEO who lives elsewhere in the province is very interested in our research, and emails me on a regular basis, inviting me to coffee whenever he is in my city. That connection, and the resulting connection to his organization, is easier to maintain than those who do not take the same initiative. Incoming relational requests are easier to manage than outgoing responsibility for maintaining relationships. This is consistent with psychological research which studied reciprocity in relationships and relative levels of effort and found that when the other person put more effort into relationship development, the relationship was considered higher quality (Maslyn & Uhl-Bien, 2001).

Occasionally, lack of connection caused me frustration as project partners would suggest things that had already been done and their level of disconnection was apparent. Some partners expressed disappointment in their lack of connection, and I began to schedule relationship-building in a more structured way by preemptively putting reminders in my calendar to check in for the purpose of connecting. However, as the project progressed, external partner management became a recurring theme, as well as a source of personal feelings of inadequacy. The types of project partners and their differing levels of involvement are detailed in Table 1.

Managing Relationships and Time Constraints

Managing the relationships between individuals involved in the project was not always something I could control, but I was intentional in attempting to smooth the path towards positive relationships by introducing people who didn’t know each other and being present at their first meetings together. I did this for new research assistants, contracted workers, and colleagues who did not know the community partners. However, even things like choosing a date for an event could be fraught with contention. Who should be consulted about which date works well? Do we choose a date based on the researchers’ availability? Do we consult the community partner organizations and learn what is happening in their schedules? If we consulted everyone, there would be no date that would work, and then we would have to face the decision about who would not be included. Managing these expectations and inclusions/exclusions was a delicate dance.

Once ethics was approved, I called the research team together to discuss each member’s ideal level of involvement. Some members preferred to be co-investigators, with regular and ongoing involvement, and there was one who opted to stay as an occasional collaborator, to be called upon on an as-needed basis. We set regular, bi-weekly meetings for the co-investigators and monthly meetings with everyone. My intention at this time was to conduct individual meetings at regular intervals with the various project leads operating through the centre. I set up biweekly or monthly meetings with each of these, hoping that this would allow me to step back from the day-to-day facilitation of each research project and instead support them in their leadership and research efforts. However, while the regularity of these meetings was helpful, their effectiveness was curtailed because institutional processes still required me to be involved in the day-to-day minutiae of each project. I will expand on these tensions in the next section.

Over time, some of these one-on-one meetings morphed into whole-group meetings. Rather than a hierarchical structure where the research facilitator led the project, and periodically reported to me, it became a much flatter structure with involvement from the whole research team. While this was more in line with community-based research paradigms, it also took more time and required me to be more detail-oriented than I preferred.

The Barber’s Got No Clippers – Need for Project Management Paradigms that Work

Several months after receiving the funding I began wishing for a project manager. At this time, I was directly leading five different research projects, supervising multiple students, preparing tenure and promotion dossiers, supervising a postdoctoral researcher, and was creating a knowledge mobilization suite for audio/video recording. I was also working to support three colleagues on projects as a co-investigator, organizing two large events, chairing a committee and serving on several others, organizing and co-hosting a podcast, and leading a speaker series. Needless to say, I was feeling overwhelmed at the number of different moving pieces within the research centre, and anxious that I would be disappointing those relying on me. I hoped that the addition of another person could help facilitate logistics, share the load, and ensure that nothing was falling through the cracks. I contacted two colleagues who I knew were involved in similar projects (large-scale, multiple partnerships) and asked for job descriptions for project managers they had hired. At my institution, hiring for this type of position is a different process than hiring a student research assistant due to different union memberships, and so this required another learning curve with new paperwork and consultations, but I was able to create a position for a research facilitator. However, I did not anticipate that university systems do not allow anyone but the principal investigator to have signing or purchasing authority, access to an institutional credit card, receive month end accounting reports, hire student research assistants, approve payroll, etc. So, although the research facilitator was able to contribute to the research and theorizing in meaningful ways, the administrative burdens were not lessened. In fact, they may have increased as I had to read hiring applications, conduct interviews, call references, and submit hiring paperwork, submit documentation to ensure this person could access software, printers, I.T., library services, email and phone access (these are all separate processes), submit an ethics amendment to add them to the research team, organize introductions to team members and project partners, and then provide ongoing supervision and approve their biweekly payroll hours.

Later in the project, once it became clear that many of the organizational logistics could not be outsourced, I wrote a proposal to use the indirect funds from the project to create a knowledge mobilization position. This was still intended to lighten my load, and also to strengthen the existing strategies we were using for mobilizing research knowledge through the centre. The proposal was accepted and resulted in another hiring process and the addition of a team member dedicated to managing social media, the podcast, newsletter, and a speaker series. Over time, the podcast migrated back to my desk, as I had the Zoom license access, which we used for recording, and because the podcast was known as a centre initiative, and often guests emailed me directly. If I had known that this person would be at the centre long-term, I believe I could have migrated those responsibilities back to her by redirecting inquiries but knowing that the funding was short-term meant that it was easier to continue to manage it directly. I posit that positions which require training, institutional access, and social networking are better served by long-term funding. As it is, short-term positions (most grant-based funding paradigms) require an immense amount of labour that do not lighten the load of the principal investigator, although they do provide critical learning opportunities for students. Part of my transition towards becoming more comfortable in my role as director of a centre and principal investigator of larger research projects meant accepting that student research assistant positions are created to provide mentoring and learning opportunities, and although student perspectives are often greatly appreciated and a significant source of contribution, they do not necessarily reduce the workload of the supervising principal investigator.

Ebbs and Flows of Project Intensity

Most research projects, regardless of size, involve some ebb and flow. For example, there might be a flurry of activity in preparing an ethics application, and then a month or longer of waiting. The same is true for the bustle of writing grant applications, gathering letters of support, finalizing budget numbers, and then waiting for adjudication. Projects may also involve seasons of activity structured around teaching schedules, weather, or other external factors.

Our research was an action research project, which involved three community consultation events. Leading up to each event, my journal shows a marked increase in the level of detail. I was meeting individually with leaders of different community organizations, and providing feedback on everything from survey design to video editing. For each event, I created a detailed agenda for all members of the team which included planning for tech support, emotional support, and other needs. I was coordinating honorarium for a knowledge keeper and ensuring proper protocols were followed, working with tech support, creating website content, supervising social media postings, and caring for the needs of the team as they were at different levels of familiarity with their roles.

In the final action research cycle, our team moved from fully online consultations to a blended format with on-site “hubs” where participants could come to join in person. This meant additional levels of intensity in preparation for both formats, and the intersections of the two. For example, while the online consultations had still required registration for participants, we now had to coordinate registration with Zoom links for online participants, and details for snacks, parking, interpreters, childcare, tech support or other on-site requirements for in-person consultations. During the analysis phases of the research, I could focus more on the research itself, but during the ramp-up to the consultations, I was preoccupied with managing logistics.

Additional Logistics

In addition to navigating the competing demands and priorities of project partners, and in addition to the research requirements themselves (ethics, methodologies, student mentorship, etc.), research leaders must also navigate project logistics including funding, timelines, university reporting processes, financial accounting, and hiring, among many others. Many of these processes require a learning curve, and some also constitute emotional labour. For example, hiring a research assistant involves learning internal university systems, as well as notifying unsuccessful candidates, which can be emotionally difficult. Table 2 details these project elements requiring navigation, based on how they appeared in my journals and notes, grouped into areas of leadership.

Facilitating Student Involvement

In the first few months of this project, I proposed a new course in our faculty called “Practicum in Community-Based Research.” This would allow more students to become involved in research, particularly those who are already employed as teachers and are not looking for additional paid hours but would like to receive course credit instead. I met with the outgoing and incoming chairs of graduate studies to discuss the protocols and procedures for this course, and wrote these, as well as the course description and course approval form. This course was approved and brought three students to work with the centre under this project’s umbrella.

Prior to this project beginning, I had started working on a flexible model of research assistant training, which used short video tutorials to teach practical aspects of research. I hosted these videos on YouTube so that students could access them easily. My main motivation for doing this was to save myself time in onboarding students, but it became a ‘happy accident’ for the research centre, as several of the videos saw a large uptake, resulting in many online followers of our research centre. This project continued to benefit from these tutorials, and also generated ideas of new topics that needed to be addressed.

Managing the Affective Dimensions of Care

Proactively managing and responding to the emotional states of the research team was something that I spent a lot of time on. Proactively, this meant ensuring I was communicating my appreciation for the involvement of the team members. For example, a member of the communications office at the university spent time editing a report that had been created in a software with which I was unfamiliar. I bought this person a small gift. I also bought similar gifts or sent personalized thank-you’s to the office administrator in our faculty, as she often helped me learn many of the new processes listed in Table 2, such as hiring forms and financial reimbursement procedures. In the same vein, I sent small gifts or cards to research assistants, the university accountant, two research officers, a librarian, a podcast editor, a copy-editor, a person who served as acting director while I was away, and a person who provided emotional support for participants during research events. I organized team dinners, open houses, meet-and-greets, birthday celebrations, and farewell parties. I also provided honorariums for a knowledge keeper who opened three research events and advocated in response to the university classifying them as a contractor (and therefore paid through the university system requiring paperwork and deductions). Sometimes these thank-you’s were reimbursable through the grant (honorariums, for example) but other times they were not eligible. For those that were ineligible, I considered them important enough to pay out of pocket. It’s important to recognize that this reflects an element of privilege. It also could lead to undue expectations or unwelcome pressure by creating a norm that cannot be replicated by others in different financial situations. It is imperative that grant funding and university systems recognize gratitude as an “eligible expense.”

I could particularly see this type of emotional care during times of transition, such as when new people joined the project, or when others left. This was true for both co-researchers, as we had changes to our research team during the project’s tenure, and for students, who filled research assistant roles and then graduated, or who were working on a shorter term, such as a practicum. This sometimes meant very practical onboarding, such as sending ethics information to a new co-researcher. Other times it meant extending invitations that could benefit others, like inviting students to co-publish even after their involvement had ended. Sometimes it meant maintaining relationships even after “official” involvement had ended. My journal describes several one-on-one meetings with former members of the advisory board after they were no longer serving on the board, for example. My journal also contains notes about personal things going on in the lives of my co-researchers. For example, I reminded myself to check in with a colleague whose son was ill, another who was going through diagnostic testing, and another who was having difficult family conversations. I considered these affective dimensions and my ethic of care as part of effective leadership.

Another aspect of managing the affective dimensions of care involved acknowledging the skills and experience represented by members of the research team. There were members who had deep expertise in areas relevant to what we were studying, and they were all nuanced in different ways. My notes detail background areas of people involved in the research, along with ideas about potential areas of contribution. I describe their previous research projects, methodological approaches, current studies and areas of interest, and community connections that could be valuable for the team. By eliciting this information from team members, I was able to show interest and respect for what they brought to the table and strategize about how best to position them within the research team. Although I do not know how it was received at their end, knowing this background made me feel more equipped to have careful conversations about things like student supervision and areas of contribution.

My journals also show several meetings that happened because of miscommunications or misunderstandings between members of the research team and community leaders. Knowing community organizations and how they operate, having skills in conflict management, and being able to communicate the needs and demands of academia is vital to avoid the kinds of misunderstandings and conflicts that can arise. Particularly in a small community, belonging can be fraught with political weight. For example, inviting a community leader to our research podcast could be seen as supporting that person’s business decisions which had caused hurt feelings from other members of the community. Fostering connection and belonging for one may directly decrease those for another. My journal shows meetings dedicated to discussing and navigating situations like this. It also shows an intensive couple of weeks of management after an unanticipated incident during a community gathering. “Cleaning up” after this event meant incident report forms, research ethics forms and meetings, creating a media plan, multiple meetings and emails with team members and research assistants involved, and many meetings, phone calls, and emails with the leaders and individuals involved in the community organization where the event took place. Reflecting on this situation and my subsequent handling of it, I can see that my focus was on preserving relationships and reassuring the individuals involved. While I was deeply dedicated to supporting the affective dimensions of care for others during this time, I do not feel I cared well for myself. I did not express the anger or disappointment that I felt, as I felt that doing so would be detrimental to the project. I was concerned with “saving face” for others, even to the point of not correcting assumptions that reflected poorly on me. Although this enabled the project to continue, I do not believe it is a long-term solution, as suppressing emotions carries detrimental impact over time (Maté, 2003). Researchers expressing their emotions and vulnerability can help with reflexivity and analysis, but can be dangerous if left unexplored, as they can lessen awareness or divert attention (Gaskell, 2008; Gemignani, 2011). Research can be difficult and emotionally draining, and although I had ethical processes in place for my participants in the event of emotional distress, it would have been helpful to have had strategies to help me work through my own emotions so that they could have benefitted the research and led to more equilibrium for myself as well (Hubbard et al., 2001).

When things are running well, a team can support one another and provide balance. This is especially valuable when team members are carrying heavy workloads, managing family lives, illness, school schedules, among others. In a well-functioning team, members can express their need for help and support at times when they need it, knowing their team members are there for support. And conversely, they are able to fill in with more time and effort when others need to step back. However, this is not something that happens automatically. It requires high levels of safety, vulnerability, and understanding since it requires admitting when help is needed and responding to that need. This is built over time. It is also a big part of why I spent time going to luncheons and teas and walks and book launches and potlucks and retirement events and campfires and talks. It is why I said yes to invitations to help colleagues in their classes or to feed their cats. It is why I invested time and effort to nominate a colleague for an award. It’s why I ordered hoodies with the name of our research centre and why I dropped off a box of perennials from my garden at a colleague’s house. This is also consistent with the literature on social belonging, which emphasizes that belonging is a practice that is manifested through everyday activities done with an ethic of care (Bennett, 2015). In my role as PI, and also as the director of the research centre, I view my role as facilitating a sense of community by nurturing an environment of care, support, and belonging through the cumulative effects of these positive interactions.

Sources of Support

Within the milieu of management stress, there were significant sources of support and learning. I met with other research centre directors, both as a group and in one-on-one meetings and found it very helpful to share ideas and resources, and to feel less isolated in my role. I also had a strong advisory board for the research centre and felt that they had my wellbeing in mind. Their advice often centred around thinking about my capacity to sustain such a heavy load, and ensuring I was not overburdening myself. Having this board was valuable when I needed to say no to things, or when I needed to talk through various ideas and hear other perspectives. However, even these sources of support required investment for them to become that way. For example, each member of the advisory board had to be onboarded and brought into the existing group. I wrote terms of reference, as the board had not existed prior to my hire. I had to negotiate with the university to find ways to provide honoraria for external board members. The same is true for the meetings with other centre directors. I invited and led conversations about working collaboratively within historical patterns of competition. Thus, even though I was able to access sources of support during this project, they were supports that I had intentionally built over time. It took individual initiative and long-term planning to build an environment in which I and others can thrive, but this is something that institutions could address by planning sources of support in advance.

Belonging, Grief, Acceptance

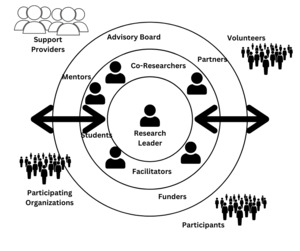

Applying Pfaff-Czarnecka’s (2011) definition of belonging which includes both collective constellations of belonging, and the individual navigating through multiple sites, I posit that facilitating a large-scale project is strengthened by partnership mapping and attentiveness to the group dynamics and emotionality of those involved. These constellations of belonging may be informal or formal, but they require the leader to be cognizant of the social and relational locations of each (Figure 1).

Dancing through this constellation can be particularly fraught when personality conflicts or conflicts over envisioned goals and outcomes come to the fore, or when power inequities result in exclusion. When conflicts are not dealt with effectively, belonging for one can be impeded by belonging for another. As Pfaff-Czarnecka points out, “belonging is thus object of continuous negotiations between individuals and collectivities” (Pfaff-Czarnecka, 2011, p. 200). At one point in this project, I made myself a “collaboration chart” so that I could keep track of the different people with whom I had discussed research and how I had said I would support them. I put this on my wall in my office in part to keep me organized but also in the hopes that it would help people understand why I couldn’t do more when they were asking for more time from me.

Towards the end of the project, I began a regular weekly research centre meeting in which all of the research assistants and facilitators, student volunteers, and associated researchers were invited. I brought homemade snacks and provided coffee and tea, and we spent time sharing what each of us were thinking about, curious about, or working on. It was intended to build a sense of belonging within the centre, to strengthen knowledge across projects, and to build on the expertise of others. This worked very well, with one member from another institution remarking that this focus on community-building was rare and greatly appreciated. However, as research assistants graduated and schedules changed, it became increasingly difficult to sustain, and eventually it became an optional meeting, and then it ceased all together. I believe this demonstrates how difficult it can be to maintain an ethic of care and relationality within the current milieu of post-secondary.

As the director of the research centre and principal investigator of the project, I had expected my role to involve more intellectual or theoretical leadership, and less logistical or procedural attention to detail. I had imagined myself as the idea-generator, the money-bringer, and the one who enthusiastically cheered for the team during knowledge mobilization. I hired research facilitators and research assistants thinking they would carry the mundane details while I paid attention to the high-level theorizing of research. Instead, almost the exact opposite happened. The research assistants and facilitators, who were often working from a distance during Covid-19 and who were not able to access institutional processes and procedures, did much of the literature exploration, theorizing, and what I would consider “research,” while I attended to the logistics that allowed the project to continue and the affective dimensions of care that allowed the humans in the project to thrive. Although transformational leadership theory (Burns, 1979) would argue that this was a point of success, since power dynamics had flattened and my research assistants and facilitators were working on higher level ideas, my journal shows that this role was not one I accepted easily. I would classify the main emotion of recognizing that the project ran smoother when I fulfilled this role as grief. The questions most collaborators, co-researchers, or students asked me were often procedural obligations in the vein of, “What is the budget limit for catering?” and not often theoretical or intellectual work such as, “How are we defining inclusion?” Looking back, I can see that the grief came from letting go of a perceived notion of what being a research centre director would entail (and what I deeply enjoy), and in embracing what was necessary instead.

Discussion

In reflecting on community-based research principles and how they were experienced throughout this project, I offer suggestions for postsecondary institutions, and also offer the following two metaphors: Conducting an orchestra without any music and fitting shoes for diverse feet.

It is imperative that post-secondary institutions consider the ethics of care and the ways in which many processes and practices of research administration can hamper this care and the resulting sense of belonging. For example, funders could include gratitude costs within eligible grant expenses. Institutions could value time and space for community-building activities and the “everyday activities” which build a sense of care and commitment to a particular place. Although it may seem absurd within our current system to list “feeding my colleague’s cat” somewhere on a tenure portfolio, the feeling of absurdity results from the system we have adopted which does not value such an ethic of care. Attending to the emotional states of researchers and their wellbeing, nurturing, mentoring, and caring for those within our orbits, and ensuring these communities of belonging can be supported over the long term must all be held as critical aspects of developing strong community-based researchers.

Universities must also consider how power can be shared within community-based research paradigms. Although this approach to research includes a strong focus on flattening power structures and including all voices, many processes and practices within postsecondary institutions are not built to facilitate this type of power sharing. Seemingly small things like having to name a “principal investigator” can be incredibly difficult within these research approaches, and can work against the aims of building community belonging. Changing research forms and drop-down menus to facilitate multiple co-leaders could be a simple place to begin.

Conducting an Orchestra without any Music

In community-based research, the research is supposed to be responsive to the needs of the community. Community partners should be involved at every stage, from planning to final knowledge mobilization. In this project, as depicted in Table 1, there were many different types of partnerships. Each of them brought skill, experience, and expertise to the table in different areas. Much like an orchestra, where talented individuals bring their musical skills and abilities to practice and perform in different sections (brass, woodwind, etc.), this research involved a large number of people, loosely grouped into communities of belonging (academics, educators, students, etc.). My job, then, was to somehow bring everyone together in their chosen roles so that they could play their best.

However, community-based research is emergent and responsive. It moves based on the will of the group. That means there is no script to follow, or, in the case of this metaphor, no music to read. I had to learn how to honour the wishes of many different people who were involved in the project for different reasons and who needed different levels of support, and somehow bring us into alignment in a way that could be productive and meaningful.

When done well, this orchestra has the potential to become like an improvisational jazz group, where each can play in an ebb and flow of involvement and where there are strong relationships, care, and a sense of belonging. At times, individual members come to the fore, and their individual skill is highlighted while other players provide support. Shared power, shared recognition, and having a shared understanding of what it means to play together are all essential elements of community-based research teams to function well.

However, as groups become larger, there is greater potential for a cacophony of disconnection and discord. The role of the principal investigator is much broader than holding expertise in the topic being studied. They must be able to work with an unwieldy orchestra, and in community-based research, facilitate the group to play without music or even without a conductor, as participatory research shares power.

Throughout this project, there were many times that I needed to adapt to shifts outside of my control. This is true for any community-based research project, but even more so when the project is large. This project involved six ethics amendments after our original approved protocol, and one unanticipated events report. We had a co-researcher go on leave, family and medical emergencies, student research assistant graduations, and retirements. As with any project involving people, life changes caused changes to availability, level of interest, level of involvement, and so on. In addition to people-related changes, there were changes at other levels as well. For example, funding and commitment changed depending on what was happening at partnering organizations. I found it helpful to remind myself of an ethic of hospitality, wherein I welcome everyone for as long as they are with me.

Like in improvisational music, I was required to respond to the unknown. The musicians are tasked with creating a song that is attentive to the music, style, audience, mood, and purpose while incorporating a back-and-forth responsivity to the other players. When done well, it demonstrates the skills of all, creates a unique song, and a beautiful experience for the audience. Adaptability, flexibility, and attentiveness are all key components to doing this well.

Fitting Shoes for Diverse Feet

As relationships deepened, I began to understand the needs and desired outcomes of different individuals and groups. For example, some colleagues were there because they were looking for a SSHRC-funded project on their CVs, others wanted to make connections in the community, and others liked the people involved and wanted to spend time together. Some students were very interested in the topic, others saw it as a way to benefit their home communities, and others wanted to do a practicum because its flexibility fit best within their home life needs. The motivations and needs were as diverse as the people involved, and as relationships deepened, so did my effectiveness in understanding and meeting these needs.

I imagine myself like a cobbler, trying to find ways to support each person to reach their own goals within the project. Sometimes the shoe pinched, and it meant I didn’t get the fit right. Other times, the shoes were too heavy and slowed everything down. And sometimes I got it right and the individual could run. An overarching theme throughout my analysis was the emphasis I put on cultivating this ethic of care, and learning how to foster a sense of belonging. Hamington and Flower describe care as inquiry, empathy, and action. They write, “Care is always a response to the particularity of someone’s circumstance that requires concrete knowledge of their situation, entailing imaginative connection and actions on behalf of their flourishing and growth” (p. 6). In the case of this metaphor, then, as I grew deeper in my relational knowledge of those in the project, I became more able to create a tailored shoe that enabled them to flourish. I take comfort in the fact that just like it can take time to find the right pair of shoes, the ability to fit only gets better and better with time, relationship-deepening, and experience.

At the same time, the cobbler needs to pay careful attention to their own feet being barefoot. Serving the needs of others without honouring my own needs during the process can be detrimental over time. This was an area that was notably absent from my journals and notes, yet which undoubtedly influenced my decisions and actions. Careful attention to my own well-being would improve the care I am able to provide others. Like a cobbler standing on solid shoes, it would increase my ability to do my job, and to do so with longevity.

Taking both the conductor and the cobbler metaphors together, it is notable that conductors are often thought of as leading from the front and centre, whereas cobblers equip from the bottom. As I have described in this article, in community-based research, power structures are flattened and power is shared. Leaders must be willing to take on the roles necessary, whether that means standing in front and calling musicians to the fore or kneeling down to check that the shoes fit well.

I believe that in order to do community-based research well, there is a critical size of relationships that can be sustained. This may be different for different people and the number of relationships and partnerships they can manage. In my own opinion, the project that is the focus of this article was too large for me as a principal investigator. Community-based research cannot be scaled up without losing depth of connection in the process, and I ran myself ragged trying to provide it at this larger scale, struggling with feelings of inadequacy and failure. Community based research, ethics of care, and relationality do not fit the paradigms of more, bigger, faster. Instead, they require careful negotiation of roles and relationships, attentiveness to belonging and team dynamics, and a dance of relational and emotional management. They require navigating ebbs and flows, student involvement, and a plethora of logistical and project management skills, which can be further complicated by institutional processes. They are buoyed by practices of gratitude and appreciation, and by support and advice along the way. When artfully practiced, community-based research becomes an experienced orchestra playing together, an improvisational medley of diverse voices confident in their belonging and able to meaningfully contribute, well-equipped with everything they need to flourish.