Although different Chilean governments have attempted to address existing inequalities in the educational system (Cociña et al., 2017; Larragaña, 2016) since the country’s return to democracy in 1989, the educational model remains deeply rooted in the neoliberal design instated in the 1980s during the former military government. Such design is also anchored in a Western-centric educational model of knowledge creation and transmission that has in fact accentuated and deepened those inequalities (Larrañaga et al., 2017; Olavarria & Campos-Martinez, 2020).

Furthermore, in a country with a long and painful history of colonialism, higher education curricula continue to be dominated by Western-centric epistemologies and practices (Aman, 2017; Basulto-Gallegos & Fuentealba, 2018), which perpetuate existing educational inequalities. Finally, as made evident by recent research (Barozet et al., 2021; Barrientos-Oradini & Araya-Castillo, 2018; Iglesias-Vasquez, 2015; Waissbluth, 2021) ongoing social changes in Chile have accentuated socio-economic and political divisions among social groups, resulting not only in more separate factions but also often in violent conflict.

Hence, this study sought to: 1) identify practices that perpetuate educational inequality leading to marginalization; 2) draw from nonviolent perspectives and approaches to design specific strategies to address this; and 3) do so by using a Participatory Action Research (PAR) design. There are numerous examples of PAR used with indigenous communities (see a detailed account in Chevalier & Buckles, 2019), youth groups (Mirra et al., 2016) and schools (Ainscow, 2010; Ainscow et al., 2003, 2006). Additionally, because of the participatory nature and aims of PAR, where knowledge and evidence are gathered from the ground up rather than being dictated top-down, examples of this approach can be found in the areas of healthcare (Baum et al., 2006; Kjellström & Mitchell, 2019; Vizeshfar et al., 2021), environmental research within specific communities (Bywater, 2014; Pain et al., 2017; Reitan & Gibson, 2012), and education (Johnson, 2021; Kemmis et al., 2014; Parrello et al., 2019). These studies provided an important foundation and rationale for this research study.

This paper elucidates how this participatory study assisted trainee teachers in their exploration of nonviolent teaching strategies. The provided analysis offers further insight that can assist researchers conducting studies in Latin America as well as those interested in using participatory approaches as a democratic act; one that relinquishes power and seeks to facilitate community-wide efforts at transformation.

The article has been organized as follows: the first section provides an overview of Participatory Action Research (PAR). The second section introduces workshops as a research methodology, while the third details how this specific study was conducted as well as the changes and modifications made between the two iterations. In light of the information presented, the last section of the study discusses the positive impact of PAR amongst the participants, as well as evident challenges and limitations encountered throughout the study.

Participatory Action Research: Orientation and Techniques

Kindon et al. (2007) place the origins of Participatory Action Research (PAR) as the work of anticolonial movements in the Global South, beginning with the work of Paulo Freire in the 1960s, continuing with Orlando Fals-Borda in Colombia in the 1970s, and later expanding into Africa, India, and other corners of Latin America. This work sought not only to improve specific situations and gain knowledge through action, as aimed by action research (AR), but to achieve radical social transformation through community-wide efforts; as Reason and Bradbury (2007) describe it:

…A participatory, democratic process concerned with developing practical knowing in the pursuit of worthwhile human purposes, grounded in a participatory worldview… [and bringing] together action and reflection, theory and practice, in participation with others in the pursuit of practical issues of concern to people, and more generally the flourishing of individual persons and communities. (p. I)

Kindon et al. (2007) identify a series of shared elements that are present in participatory studies and that offer a clear indication of the direction PAR takes; to begin with, participants are actively involved in every stage of the research process and work in collaboration with the lead researcher in the execution, reflection and refinements of the study. Second, it is not only context-bound but also incorporates ideals and principles that are autochthonous to that specific community. Finally, PAR should lead to the co-construction of knowledge through shared reflections on the actions undertaken; in fact, the credibility and validity of this co-creation should be ascertained by determining if a specific problem was solved through collective action or if the community’s self-determination was in any way augmented.

In looking at methods, PAR challenges the traditional social science approaches in that it first requires the researcher to surrender control and assume the role of a facilitator rather than someone who decides every step of the process, sets the agenda and otherwise makes every decision in terms of the direction the research needs to take. As such, some of the most common methods used in PAR can be seen in the box below, adapted from Kindon et al. (2007).

Critiques and Challenges

Participatory approaches are not without their detractors and critics; perhaps the most prominent of these have been Cooke and Kothari (2001), who warned against the risks of it being “tyrannical”; Mosse (2001), who called it manipulative; or Brydon-Miller et al. (2004), who described it as androcentric. I will discuss some of these and present my counterpoints.

Cooke and Kothari’s Critique

The first criticism I will analyze is Cooke and Kothari’s (2001), whereby they challenge the validity of participation not only to empower, but also as a way to challenge the very power structures that participatory approaches seek to defy. However, the critique centers on two elements that are disputable: first, they define participatory research as a technique, whereas Kemmis et al. (2000, 2005, p. 2009) characterize it as an approach in which the technique (or methods) is designed to fit with the approach’s aims. Secondly, much of the analysis is rooted in what I argue is an elitist concept of what is considered “valid knowledge”; as outlined earlier in this chapter, participatory action research seeks not to gain knowledge in the traditional sense, but to produce changes to the way a particular community does things; it is from the shared analysis of these practices and changes that the new knowledge is gained, practices are changed, and the existing practice architectures can be challenged.

A second argument Cooke and Kothari make in their critique of participatory approaches concerns power and power structures: knowledge, they contend, is “culturally, socially and politically produced and is continuously reformulated as a powerful normative construct” (p. 141). Consequently, rather than shifting power imbalance, participatory approaches risk reasserting the same power and control within the same individuals, groups, and knowledge systems they seek to reverse; part of this argument is the observation that power structures do not only exist at a macro level of large institutions, but can be present at the micro level of a smaller research site. With this in mind, I was very clear regarding my intentions to relinquish power and hand it to the participants themselves; however, I do acknowledge that this transfer of power was a difficult, if not an impossible, task. This was certainly not because unwillingness on my part; the structure and constraints of a university setting where the study was carried out were difficult to overcome, and the hierarchical differences present in the teacher/student relationship were always evident. In spite of this, every effort was made to facilitate participants’ choice whenever that was a possibility and they were indeed able to make an important number of choices concerning discussion themes, approach to the weekly tasks, degree of desired involvement, and how to generate date.

Additonal Critiques

Presenting a different critique, Mosse (2001) examined the development industry in South and Southeast Asia; his observations provide a great deal of insight into the power structures surrounding NGO funding of forestry studies in India and Indonesia, as well as the “behind-the-curtain” politics concerning ways of handling local knowledge. For instance, he noted how the voices of women were absent from the conversation, as women were limited in being able to voice their opinion; furthermore, Mosse noted how local knowledge was built on existing power structures, and much of the research planning stage was done behind closed doors by those in power. Finally, he observed that the negotiating for consensus — which as McTaggart et al. (2017) remark, should be unforced — was shaped by existing power relations and hierarchies in the local communities.

What is important to take from Mosse’s research, the issues therein also explored in educational settings by Nofke and Somekh (2013), is the awareness of how power structures can stifle the voices of those who have been excluded or minoritized. These include, as detailed in the section “Inequality context in Chile,” students from Indigenous backgrounds, immigrants, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, those who have experienced exclusion for socio-economic reasons, people with disabilities or anyone else. The initial challenge for this study was for me, as the research facilitator. to observe how different participants were faring in making their voices heard and to ensure there was ample space for their engagement. However, it is important to note that as in any participatory process, at different times individuals chose not to participate or to engage. Though I did encourage them to do so and approached them gently to find out if they needed help, their participation and engagement remained entirely voluntary.

To conclude, and critiques notwithstanding, every effort was made to make this study as participatory and empowering as possible; participants guided the discussions during the workshops, determined what issues needed to be addressed and how to best tackle those issues. Furthermore, data collection was carried out with consideration to individual and group choice — meaning that the participants chose how to record and present data.

Methodology and Research Design

Position Statement

Holmes (2020) defines positionality as “an individual’s worldview and the position they adopt about a research task and it social and political context” (p. 1). Therefore, and before I present this thesis, I will briefly describe and acknowledge my position as a researcher.

This position is fundamentally informed by two things: my Buddhist spiritual beliefs and my vision of education as a practice of social transformation. Buddhism has shaped my worldview into one where people don’t exist in binary terms, though we often think in such terms (male/female; good/bad; oppressed/oppressor; black/white). As a result of my Buddhist beliefs, my view is that perspectives that conceptualize things as in opposition, such as Cartesian dualism, exacerbate binarism, as do the social constructs we have built around issues of identity, which have served to exclude rather than include, and to divide rather than unite. While I acknowledge the profound and often painful implications generated by Western views on racial, sexual, and cultural identity, my position is that tackling these issues through the recognition of our differences and each other’s shared humanity, such as through restorative justice and nonviolence efforts, is the most sustainable path towards social inclusiveness.

This in turn has guided my view of what education should be; such a view, contained within the critical paradigm (Asghar, 2013), argues for an examination of our social reality, identifying the actions that must be taken to change and improve it, and providing a clear path forward. This examination, identification, and transformative action are best approached within the framework of critical pedagogy, starting with the work of Paulo Freire (1970) but more crucially through the work of bell hooks (1994, 2008) and her writings on engaged pedagogy and critical thinking. Her perspective that “no one is born a racist” (1998, p. 25) resonates with and informs my own vision that education can furnish a pathway for transforming exclusionary views into more inclusive ones. In my case, this inclusiveness is fundamentally guided by Buddhist thought and particularly by the teachings of Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh (1987) best encapsulated here:

Seeing that harmful actions arise from anger, fear, greed, and intolerance, which in turn come from dualistic and discriminative thinking, I will cultivate openness, non-discrimination, and non-attachment to views in order to transform violence, fanaticism, and dogmatism in myself and in the world. (p. 5)

Transforming violence, dogmatism and discriminative thinking within a classroom setting by promoting dialogue, democratic participation and social awareness, is perhaps the most fundamental aspect of this project, and these were key aspects to the project. While I acknowledge the tensions that exist between critical theory and Buddhist philosophy, it is my position that in spite of these tensions, both of these worldviews share an approach to social justice rooted in the re-humanization of others, and in the transformation of our social world by tackling the factors and systems that oppress, and which cause suffering and marginalization. It is also my position that the spiritual aspect of critical pedagogy is both present and often unexplored in the work of two key proponents whose work I draw on, namely Paulo Freire, who was raised by a spiritualist father and a Roman Catholic mother, and bell hooks, whose work is — by her own admission — influenced by the work of Thich Nhat Hanh (hooks, 1994). This spiritual overlap is key to my decision to draw on works of these thinkers.

The methodological choices made are similarly guided by these ideas. What follows is the description of a participatory action research project built around a series of collaborative workshops, which incorporate a range of practices, exercises, and overall approach informed by my aforementioned positionality; examples of these are the research approach and methods adopted (workshops within a participatory action research design), the use of self-enquiry practices, empathy-development exercises, reflective reading, and creating space for the collective exploration of nonviolent approaches to inequality.

Research Design

The figure below (Fig.2) illustrates the overall participatory design and flow of the research study as it was planned and occurred.

Workshops

Within the framework of research methodology, Ørngreen and Levinsen (2017) describe workshops as “an arrangement where group of people learn, acquire new knowledge, perform creative problem-solving, or innovate in relation to a domain-specific issue” (p. 71). I found this to be a suitable structure both within the scope of the chosen design and the research context, as participants discussed and generated ideas in order to tackle specific social and structural issues concerning violence and inequality.

The workshops were undertaken in a blended pattern that combined conceptual and open formats; this means there were pre-designed activities (reading assignment and reflection worksheet) while at the same time there was space for participants and the researcher to continuously negotiate format and content during the iteration of the workshop cycle; the latter allowed for changes to occur spontaneously as unforeseen elements emerged.

Workshops were structured as follows:

-

A pre-session reading assignment that varied depending on the workshop’s topic. Such reading was accompanied of a reflection-type worksheet where participants were asked to record answers to specific question, which they were requested to bring to the face-to-face session for sharing and discussion.

-

The workshop itself began with 15 minutes devoted to a contemplative practice. A key element of this research was the inner work done through self-enquiry, which in turn might impact the relationship amongst participants, and this was the rationale for incorporating contemplative practices. Participants were asked if they desired to partake in this activity, and if they did, instruction was provided for the practice chosen on that day. Examples of these practices were loving-kindness meditation, quiet breathing, silent meditation, journaling, and empathy exercises.

-

Thirty minutes were devoted to share and discuss the questions from the pre-workshop reading tasks contained in the assigned worksheet.

-

The remaining of the session was spent on what Kemmis et al. (2014) define as “communicative action”:

…(a) intersubjective agreement about the ideas and language they use among participants as a basis for (b) mutual understanding of one another’s points of view in order to reach (c) unforced consensus about what to do in their particular situation. (p. 35)

- The last 10 minutes were devoted to finalize and deliver their reports by presenting them to other groups.

Research Site and Participants

The first iteration of this study was carried out with a group of students enrolled at Universidad de O’Higgins (UOH) in Rancagua, Chile. Twenty-eight students signed up originally, but the average number of participants was 13 (the number ranged from 10 to 16, fluctuating each week). The participants were fourth-year students pursuing a degree in English Teaching; some had teaching experience, either as a teaching assistant or because of their practicum, but generally, their in-classroom experience was limited.

We met eight times; the first meeting was an informative session that provided an overall description of the study and students were formally asked if they wanted to join. Those who said yes were given the information documents and signed the consent form. In total, 28 students consented to participate, with one formally dropping out and another joining the week immediately after. It should be noted that this particular cohort had never met in person. They had begun their university studies in 2019 right before the October riots in Chile; the level of damage to public infrastructure and the amount of daily marches and demonstrations were such that the government decided to move all educational activities online. This decision coincided with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which means that from 2019 until 2022, these students had only received online classes and had never met face-to-face.

The second iteration of workshops was completed at the Universidad Católica de Valparaiso (PUCV); unlike the first iteration, where the workshops were embedded into an existing class, this time the university asked me to use the overall theme and content of the initial workshops, turn them into a full 14-week course, and make this part of the university’s curriculum for English-teaching majors. The class was titled “Radical Pedagogies, Nonviolence and Change” and was offered as an elective for students majoring in English teaching. We organized a presentation of the course to prospective students, after which 25 students enrolled. The final number of participants was 22. This group was composed of 14 males and 8 females, who presented a more geographically mixed cohort. While some students came from nearby rural areas, most came from urban centers.

The Participatory Action Research Cycle Within This Study

The participatory action research cycle begins by contemplating how a concrete condition might be enhanced. Following that inquiry, we engage in a cycle of action and reflection. While there are several versions of this cycle, the chart by Pain et al. (2017, see below) is particularly useful in that contains several of the same points of reflection the participants and I engaged in. With this in mind, there are four concrete areas where the study succeeded as a Participatory Action Research project, which I detail next.

Workshop Themes for the First Iteration

The first iteration of the project consisted of seven participatory workshops as detailed below.

Workshop 1

Research training and introduction of key concepts

This session was used to establish the research agenda, identify key roles and responsibilities, and discuss the possible (and expected) outcomes of the project.

Workshop 2

Theme: What is Nonviolence?

Reading/worksheet: See appendix “Week 2 Readings” retrieved here: https://tinyurl.com/cjnczfks

Workshop 3

Theme: Interdependency

Reading/worksheet: See appendix “Week 3 Readings” retrieved here: https://tinyurl.com/4v57vk4a

Workshop 4

Theme: Nonviolent Communication

Reading/Worksheet: See appendix “Week 4 Readings” retrieved here: https://tinyurl.com/yc3hkbxa

Workshop 5

Theme: Mindfulness and Inclusiveness

Reading:/Worksheet: See appendix “Week 5 Readings” retrieved here: https://tinyurl.com/55aen5hv

Workshop 6

Theme: Democratic Education and Shifting the Power Balance

Reading/worksheet: See appendix “Week 6 Readings” retrieved here: https://tinyurl.com/vvb7xsrf

Workshop 7

Final discussion and feedback on the workshops. We reflected on the design, work accountability, and the amount and type of information required for the project to succeed in the next stage, considering how it had unfolded.

Turning Reflection into Action

Phase One of the study presented several opportunities for reflection that turned into modified action. The first was in the realm of participant accountability, particularly for the online component. In spite of their high level of collaboration during face-to-face sessions, participants did not respond to my emails or any communication I sent through the university platform. The number of individual reflections submitted declined from Weeks 1 to 7, going from 15 the first week to 6 in Week 7. Even though the workload had been established with the participants themselves and the university, it proved too much for participants and had to be reduced. This initially heavy workload led to several students leaving the study as they could not balance their academic work and what the workshops required. This experience, conversations, and suggestions led me to make a different arrangement with the second cohort; instead of individual reading and reflections, participants were divided into groups that engaged in the reading using a jigsaw approach, and the reflections were done as a group. This resulted in increased participation, improved collaboration, and a higher rate of reflections submitted, which in the end meant each week yielded data.

The second challenge expressed by the first cohort was the use of meditation at the beginning of the sessions; I started this study with the intention of providing learners with basic instructions on simple mindfulness exercises, such as awareness of the breath or silent meditation. These practices, however, did not fully engage the participants; the silent meditation proved particularly difficult. In fact, during our last meeting (which was entirely devoted to feedback), when asked which element of the workshops they would eliminate, silent meditation was the only component some students said was not particularly useful. Their insight included that “meditation is not for everyone,” “it was difficult to be still,” and “it’s not particularly useful.” With this in mind, I decided not to do guided meditation during Phase Two, and to focus on activities that directed attention at developing empathy and encouraging the development of a sense of community and reflexivity.

Yet another important point of reflection leading to changed action was the participatory element in PAR; I had originally envisioned a study with high levels of participation and collaboration, with constant feedback and contributions from participants leading into a participatory research process. This vision, however, faced several challenges: to begin with, students from the first batch did not have an interest in being an active part of the research process (as voiced in one of the sessions). Although I regularly collated and shared the discussion findings and solicited feedback and suggested changes, no feedback was given. I regularly asked participants for ideas on future contemplative practices they might want to do, or readings/topics they might like to work with; I shared with them the results of their final feedback session asking for further contributions and none were received, and no new ideas were put forth.

Differentiated Action

Having reflected upon these factors before starting the second iteration, several things were different with the second group of participants. First, having understood that Chilean students would prioritize higher credit, mandatory classes over low-credit electives, I focused on facilitating participants’ choices where they were more likely to occur. For instance, we discussed the most sustainable way to approach weekly tasks, and agreed to form weekly reading groups rather than submitting individual assignments. We also looked at topics scheduled for discussion and adjusted were made based on participant input. They specifically asked for a session devoted to LGBTQIA+ inclusiveness; nonviolent classroom strategies; and for videos as part of their study resources, all of which was integrated and resulted in high engagement. Considering a feedback point from the first group — that there had been no opportunity to bring the workshops’ ideas into their classroom — three sessions were devoted to peer teaching to offer an opportunity to put theory into practice. Participants chose their own topics, selected a contemplative practice to use at the beginning of the lesson, and prepared a 30-minute lesson which they taught to their peers.

Finally, a key point of PAR is sharing findings and collaborating in analysis. This is a point where this study fell short. I have previously detailed how participants were asked to submit individual reflections; while this had the advantage of delving deeper into the reflection prompts, it also did not allow for sharing, commenting, or discussing in order to widen our reality and perhaps find common points that emerged (of which, upon analysis, there were many). During the workshops themselves, participants presented their findings to other groups, but there was not time built in for feedback or some shared analysis. For the second iteration, due to further time constraints, each group submitted their work directly to me; in this case, given my access to the university’s Moodle platform, I could have set up a blog or forum that would have provided an opportunity to comment on other people’s work, views, and ideas.

In summary, my original vision of PAR was not fully realized. However, there was still a very high degree of collaboration, including the ideas presented by the participants in their individual and shared reflections. Their group posters and presentations were also fully their own, as were the findings made in: 1) existing violence in classrooms; 2) strategies to deal with violence; and 3) how the perspectives studied might help foster nonviolent learning environments. Several elements of PAR according to Pain et al. (2017) were present, such as enabling participation, building relations, working together in collaborative tasks, and collaboratively deciding on issues. Findings were sometimes shared, but this was also a point — particularly with the second group — where the study would have benefitted from further instances of collective participation and input.

Because at PUVC the course extended to 14 workshops instead of seven (albeit with shorter sessions), the design also changed; the first four weeks of the course were entirely online and the remaining 10 were in person. Considering that the number of reflections submitted by the cohort declined substantially as the study went on, the weekly reflections element for the in-person part of the course was eliminated. However, I did maintain the reading and reflection assignments for the online portion of the course; the reading, upon the participants’ suggestion, was done in groups using a jigsaw approach. The extended schedule allowed me also to explore other dimensions that were not discussed in depth the first time, such as inclusiveness from the perspective of sexual orientation and gender, the incorporation of feminist perspectives, and exposure to practical applications of nonviolence education. All of this was added for the second iteration, as was time for short, micro-teaching sessions. These allowed participants to focus on a specific topic we had discussed and plan a classroom activity designed to raise awareness of nonviolence and inclusiveness anchored in their chosen perspective, which included nonviolent communication, interculturality, compassion, and humanity.

Workshop Themes for the Second Iteration

As explained earlier, the second iteration consisted of a 14-week elective course, divided in two stages: 4 weeks of independent study done online and 10 weeks in person, each 70 minutes long. This was due my teaching commitments at the University of Glasgow, which ended once the Chilean academic year had already begun. The university in Chile and I came agreed that this strategy was the best way to proceed. The weekly content and themes were as follows (the links will take the reader to the reading materials and worksheet used by the participants):

Week 1

Theme: Nonviolence

Week 2

Theme: Indigenous Perspectives on Nonviolence

Week 3

Theme: Cosmopolitanism and Interculturality

Week 4

Theme: Contemplative Pedagogy and Mindfulness

Beginning in Week 5, when the in-person stage started, each week’s reading was accompanied by a series of questions inviting the participants to reflect on the weekly topic. This reflection was then submitted through the university Moodle and comments were provided. Although this was ungraded work, I was expected to provide feedback as an acknowledgement of students’ personal reflections.

Week 5

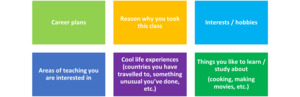

This session was devoted to getting to know each other, as most participants were meeting for the first time. The first task was to discuss the following topics with different people:

Week 6

Theme: Nonviolent Communication

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Pm2lkL8CFbyzvFBiOSmf11NdfKFsbEad

Week 7

Theme: Fostering Democratic Learning Environments

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1_FIMinofJeM_RlH7bFbOogaz9WdmvOjP

Week 8

Theme: Feminist Pedagogy

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1v2nvp24b5mYrKfyXymagz0-LTa8sx1Ch

Week 9

Theme: Gender/Sexual Equality and Inclusiveness

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1267OJ8efnMoFIPGpD2ecbtIdu2d1HH8P

Week 10

Theme: Nonviolent Strategies in Education

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1rIWpUySwMc8FUR_waUPUg5-4zWSi8LjC

Weeks 11, 12, and 13

These three weeks were devoted to peer-teaching. Participants filled out a survey expressing the theme they wanted to focus on choosing first one of the following themes:

-

Cosmopolitanism and intercultural communication

-

Indigenous knowledge and interconnectedness

-

Nonviolent communication (compassion, empathy, and non-judgement)

-

Sexual and gender inclusive education

Week 14

Feedback on the course: we discussed the degree to which participation had worked, possible directions for them individually, and the implications of the project for the wider community.

The PAR Cycle: Ensuing Transformation and Paradigm Shifts

This section focuses on the role played by the study’s participatory element on how some of the paradigms held by participants shifted as the study unfolded. As the sections below will show, this research project succeeded on four key aspects as discussed by Pain el al. (2017):

1) It allowed participants to collectively decide on what actions and strategies were more suitable within their own contexts; 2) Through their collective deliberations, discussion and peer-teaching, it enabled participants to bring together reflection of theory and practice; 3) It generated functional knowledge; and 4) It brought participants together as a community.

First, it is essential to revisit the concept of “participatory” in the context of PAR, and what PAR itself aims to do. Kindon et al. (2007) define PAR as an approach in which both participants and researchers collaborate in the exploration of specific problems to bring about change or improvement. PAR seeks to subvert the hierarchical and skewed power relation between researcher and participants, which often manifests in impositions rather than collaboration (Kindon et al., 2007). Within the limitations of this study, I aimed to facilitate as much participation and collaboration as possible while reducing imposition to the virtual minimum during the workshops/sessions, instead focusing on selecting the reading material, formulating the post-reading reflection question, and preparing questions to jump start the in-session discussions.

This means that, within the possibilities of this study, participants had the freedom to make changes to content, correct findings, choose topics to analyse live and for their peer teaching, the format for submitting their reflections, and how many of the given questions they wanted to answer (if any at all). Although not all these freedoms were used, the knowledge generated and constructed — both in the type of violence, discrimination, and exclusion found as well as in the practices and strategies suggested to reduce them — was entirely the students’ own. Herein lies, in my view, the impact of participation in the study: the entirety of the data and insight gathered stems from the participants’ shared effort and collaboration in examining their personal and professional experiences with each of the theories and perspectives discussed. This insight, in turn, provides an insider’s view into how violence unfolds and manifests in Chilean educational communities, particularly in the classroom.

Perhaps the most significant paradigm shift that occurred throughout the study was in the participants’ view on what nonviolence is and the role it can potentially play in promoting greater inclusivity. This shift is of paramount importance, as the other changes in perspective detailed below are intimately bound to this newly acquired understanding. In some cases, this shift brought a new awareness of how much violence has to do with our thoughts and intentions, such as in the case of UOH2:

What resonated the most with me was the idea that violence is related to what we think. Our thoughts towards people. I started to think that I should not think bad things about other people because it would be excluding them in some way, and it affects the way I see them. I need to start seeing them as equal without moralistic judgements. (UOH2)

Often, paradigm shift manifested within the individuals’ personal lives and experiences, as reported by participants PUCV4 :

…My approach to the concept has definitely changed as a result of what we have discussed as a group throughout the lessons. If before I would talk about nonviolence as, “I’m going to avoid responding to this person because otherwise I’m going to get angry with them,” now it is more like, “I’m going to talk to this person, calmly, about the things that seem wrong to me and that could be different or modified.” And a level of respect for the other person must always be maintained, even if they get on your nerves. – PUCV4

This level of insight into their inner journey, ranging from thought to action, is important because, as Thich Nhat Hanh (2004) argues, the process of changing collective consciousness begins with the transformation of our individual consciousness. This transformed consciousness, in turn, or what Galtung (1996) described as a necessary condition of health before peace can exist, and which must infuse every aspect our lives, is what hopefully will permeate and shape a teacher’s relationships and interactions with their learners. I argue, as did the participants, that this consciousness must be accompanied by what hooks (1994, p. 15) called self-actualization: a practice in which the practitioner must devote a concerted effort towards their own well-being to positively impact others.

In that sense, evidence from participants points to the fact that the practices we engaged in — contemplative activities, reading and reflecting on the cultivation of nonviolence and nonviolent action, collectively thinking about ways to address violence — did have a self-actualizing effect which manifested in a willingness to engage with others differently. This is well exemplified by the two insights below; the first emphasizes the value of self-care considering possible challenges in bringing inclusive, nonviolent practices to the classroom, while the second highlights the importance of teacher self-development if we are to engage in social justice efforts:

There are different things I can do for my own well-being. As a person, I think it is necessary to learn to have a healthy relationship with myself, to achieve this it is necessary to go to therapy and try to improve day by day. On the other hand, as a future teacher, I know that I will have complicated days when things don’t work out. This is why it is necessary to maintain good communication with my students, and that we can all express our needs without fear. – UOH8

After reading the materials, I considered new perspectives. One of them is the spiritual aspect of the role of teacher; whenever I thought of social justice before, I had never considered this, and it’s something I will try to practice. In relation to the inner work we do, and what we do as educators in terms of social justice, I believe that by doing these practices like self-exploration and self-understanding that dive deep into the inner self, we can also promote them to our students. – UOH14

Changes in perspectives concerning nonviolence and inclusiveness had a second, equally relevant dimension that relates to how participants saw their own role as teachers in promoting these values within the classrooms and amongst students:

I learned that we as teachers can do a lot of things that will help our students to develop and participate into a healthier community. Although here in Chile the planification of classes is very restrictive, we can use the materials and our tools to teach the students through in different ways even though the school may put a stop to us. – PUCV 20

I have a considerably better understanding of what nonviolence and inequality mean. It surprises me how a classroom and a school can instil in students greatly variegated values and beliefs, not only in education but also in themselves. Access to education and opportunities must be open to anyone and everyone. – PUCV 11

The viewpoints offered here by pre-service teachers who, according to their own shared experiences, had been bullied at school by classmates and teachers even to the extent of physical violence, provide an optimistic outlook into the possibilities of nonviolence education in their current context, and into the way they see themselves as nonviolence practitioners. In fact, I argue that what participants offer here links to and builds upon Chubbuck and Zembylas’ “critical pedagogy for nonviolence” (2011). The authors’ work identifies several areas that bear relation with these participants’ insights: nonviolence as curriculum and nonviolence in the relational classroom climate. In regard to the first of these dimensions, Chubbuck and Zembylas (2011) point to the role of their teacher participant in guiding the conversation towards questioning the way violence has been historically used as a means of domination; concerning the latter dimension, they note how that teacher’s approach was one filled with consistency. This consistency manifested in the way she remained committed to the practice of nonviolence even in the face of challenges, such as when her students acted violently and through personal struggles with anxiety.

The last paradigm shift I examine here concerns participants’ awareness of the role of empathy in developing inclusiveness and practicing nonviolence. Early conversations with participants revealed how concerned they were with how they themselves were treated; examples given during our discussions revolved around how others spoke to them, the things that were said to them, and the actions experienced by them. By the end of the workshops, participants were instead discussing the importance and impact of treating others compassionately, the significance and value of using language kindly and non-judgmentally, and in more general terms about the impact of contemplative practices in their overall pedagogical outlook, classroom relations, and emotional awareness. This shift has been documented through the reflections expressed by the participants of the first cohort during group discussions on the last session held, as below:

Group 1:

UOH11: Yes… and that impact our relationship with others, as we start becoming more empathetic. For example, I used to think, “How will I empathize with someone who is a racist?” But now I understand that perhaps that person comes a from a different generation, so I understand them and accept them. As teachers we want to change the world but it’s hard.

UOH16: What helped me was that activity where we had to see each other as someone just like us. It helped me see the other person as someone who is also human, also feeling.

UOH11: Yes, we forget about our humanity… even though we are humans.

UOH12: As long as one is well, the rest doesn’t matter. And this is wrong.

UOH6: Of course, it’s important to take care of our own wellbeing, but it’s wrong to put ourselves in the center. We have to be a priority to ourselves, but it can’t be like “me me me me.”

UOH11: Exactly, it’s different to be self-centered than to have self-esteem.

There are several different dimensions of interest in the excerpts above. The first concerns how the participants identify the challenge of empathizing with those identified as the perpetrator, while learning to see them as “also human, also feeling.” Our practices during the research study did not involve a direct exposure to violent social events; however, the principle stands: when we only focus on the violent act being perpetrated, we have an incomplete assessment of why it was carried out. Thich Nhat Hanh (2001) argues that when we see someone’s anger, we need to also understand that these individuals carry with them their own suffering manifesting through their actions. Several participants acknowledged that we all have our own personal stories. For example, one participant noted:

In my point of view every contemplative practice really did have an impact but the one that stuck with me, I think it was the not putting people into boxes (that was the one where you said to go to the front if… right?) because most of the time we tend to classify people in some ways without knowing much about them and then when we get to know them we get why they are the way they are. – PUCV7

The expansion of the initially narrow circle of concern, which in my view was fundamental in cultivating inclusiveness, involved careful planning in two specific areas: one was the reading materials for each week, and the other was selecting contemplative activities that addressed the main weekly theme. For instance, for the theme of nonviolence, I led a meditation on loving-kindness (Chödron, 2006), which raises practitioners’ awareness of love as an all-inclusive dimension rather than limiting it to those close to us. During the week devoted to discussing interconnectedness, participants engaged in an exercise titled “Compassion Practice,” which asked them to become fully aware of the person in front of them while silently contemplating that that person was a human being just like them, with feelings and emotions just like them, and very likely who had experienced hurt, disappointment, and anger, just like them.

Limitations

Although I have discussed several limitations of this study in earlier sections, I will now discuss two specific factors that limited this project in concrete ways. The first of these is the lack of a participatory analysis, while the second concerns the degree to which democratization of the research process was achieved.

Concerning the first of these points, neither the analysis nor dissemination of results were done collectively nor agreed on with the participants. Although each cohort came up with their own strategies to deal with the violence they themselves had identified, how the data was shared was decided by me. With the first cohort, I collated the data from their posters, wrote the data on a Word document, and shared it with them on Moodle. In the second cohort, the groups shared their ideas with each other. Further, the reading materials were all chosen by me; although every effort was made to have participants go through the reading lists and choose what they wanted to read, the reading and reflection questions ended up being entirely my work. In brief, all of these points were part of the learning experience and presented me with a series of considerations that need to be taken into account in future work: building in more time to develop trust with the participants, devote a section of the study to co-develop research questions, discuss the existing issues as a community and how we can collectively research them, and importantly, consider how we as a group might analyze and share our findings to make the study more fully participatory. For instance, in their healthcare research, Gray et al. (2001) discuss something I found particularly relevant concerning research questions, which was a primary concern for me. As they document, successful participatory studies in healthcare have always involved meticulous negotiation between participants and lead researchers at every stage of the research process, so researchers brought their questions to the breast cancer self-care group they were working with. However, the participants then had the opportunity to critique and formulate additional questions they were interested in investigating. This approach could have been helpful in addressing the lack of input on the initial stages of this study.

Consequently, and what can be inferred from the above, navigating the participation required by PAR and making the classroom a truly democratic research environment is a dimension that requires more work. What is speicifcally needed is robust participant training. The teacher-student relationship still retained its hierarchical roots, with participants referring and deferring to me as their teacher for decision making; therefore, shifting the classroom dynamics — specifically in relation to research, which is seen as a stratified endeavor — necessitates a sustained, long-term effort that can help shift this relational paradigm and allow for participants to ease into their role as co-researchers. As Scher et al. (2023) and O’Brien et al. (2021) note, participatory research requires rigorous and constant reflection on the power differentials that exist amongst the stakeholders. Such reflection and the change it must necessarily undergo necessitates time: time to train participants, time to understand what is required of each, and time to build the necessary trust for participation to take place.

Discussion

The findings of this study are consistent and broadly in harmony with previous research on: the meaning and manifestations of violence (Galtung, 1969, 1990, 1996); the ethics of nonviolence (Butler, 2020); intercultural perspectives on inclusiveness (Aman, 2012, 2015, 2017; Appiah, 2007, 2018; Bardhan & Sobre-Denton, 2013); decolonial approaches to nonviolence linked to spiritual traditions (Tutu, 1999); the practice of contemplative pedagogy (Barbezat & Bush, 2013; Lin et al., 2019); and, finally, how nonviolence education might contribute to a social justice framework (Wang, 2013, 2018, p. 2019). Consistency with previous research notwithstanding, this study also offers valuable new insights in the Chilean context. As I have noted, there is a wealth of research from Chilean scholars on a range of educational issues such as: HE policy (e.g., Alarcón López & Falabella, 2021; Garreton et al., 2011; Mora Olate, 2018; Rivera-Polo et al., 2018; Slachevsky-Aguilera, 2015); school and university curriculum (e.g., Basulto-Gallegos & Fuentealba, 2018; Cisterna et al., 2016; Mejia-Navarrete, 2015); or inclusive education (e.g., Castillo-Armijo, 2020; Gutierrez-Pezo, 2020; Martinez & Rosas, 2022). However, this body of research does not focus on the use of participatory methods, nonviolent approaches to education, or non-Western knowledge systems to address exclusion and discrimination, even when evidence points to a need for changing pedagogical practices towards nonviolent ones, as Lopez et al. (2021) have argued. It is here that this project makes its contribution, offering practical suggestions on how to deal with linguistic and cultural exclusion of migrant students, how to improve inclusiveness in teaching materials and pedagogical practices so marginalized communities are actually represented, and how to develop a greater collective spirit through community-building endeavors. It further offers a critical view of the current state of Chilean education from a social, cultural, and structural viewpoint; alongside that, it presents us with the participants’ vision of what this educational context should look like and how what they learned throughout the project can potentially help them realize that vision.

This study also makes very concrete contributions to theoretical and practical knowledge in several areas; for instance, participants gained a solid understanding of violence not only in its direct, physical form but as an expression present in unequal structures and exclusionary cultural values. Participants’ insights also revealed their comprehension of the role of violence in producing and perpetuating inequality; this was knowledge that they recognized not having had previously. They also showed a strong grasp of nonviolence as an engaged, active practice, while their previous understanding of nonviolence was limited to pacifism and non-action. The findings show that the theories and practices implemented throughout the project had a transformative effect in the way the participants saw themselves, their students, their peers, and their interpersonal relationships. This shift was reflected in a more empathetic and compassionate view of others; a willingness to engage with the world around them in a nonviolent manner; and an explicit desire to learn more about nonviolence, contemplative pedagogy, and nonviolent action as a means to social justice.

In relation to this, there are specific philosophical, theoretical, and practical areas where this project added missing perspectives: feminist and contemplative pedagogies, ubuntu, NVC, and case studies from Africa and Asia and Cosmopolitanism were either little known or completely unfamiliar to the large majority of participants; by the end of the project, they had become an important part of their decision-making process. Although there were , as I have discussed throughout this paper, limitations to this project, this research succeeded in creating a collaborative space where participants were able to openly discuss their views on each of the themes presented, and more importantly, where they were capable of collectively strategizing ways to deal with educational inequalities. It is in this participatory effort, in the themes studied and in the practices we engaged in as a collective, that this project contributes the most in a context where nonviolent approaches within classroom settings were absent.

From a methodological perspective, it should be noted that research in Chile is highly institutionalized and dictated top-down, either from universities themselves or through government organizations, which leaves little if any room for self-determined research agendas. Tuhiwai-Smith (2012) notes as much in relation to Indigenous research, and this helps perpetuate what Quijano and Ennis (2000) referred to as coloniality of power. That being the case, however, evidence from this project has shown that there is both the wherewithal and willingness from institutions to facilitate the use of participatory methods; even during the time when I was making initial contact with Chilean universities, there was a strong sense of enthusiasm and openness towards this approach and specifically on the theme of nonviolence. Kumar (2023) notes that action research — and I might add that this involves any of its articulations, such as CPAR or PAR — represents not only a sustainable alternative to existing models, but also an opportunity for practitioners to identify problems and context-specific solutions in an autonomous manner; Kumar’s collaborative research with teachers was carried out in the Maldives, Nepal, and Afghanistan, places, she indicates, which are low in economic resources for research but where engagement and collaboration were high. This mirrors my own experience in Chile, where research was conducted in regional universities with many low-income students who attend for free, where no external funds were used, where participants were not asked at any point to disburse their own money, and where the greatest investment required was time.

Conclusion

To conclude, navigating the participation I had envisioned and making the classroom a truly democratic research environment is a dimension that requires work and robust participant training. The teacher-student relationship still retains its hierarchical roots and shifting the classroom dynamics — specifically in relation to research, which is seen as a stratified endeavor — necessitates a sustained, long-term effort that can help shift this relational paradigm and can allow for participants to ease into their role as co-researchers. As Scher et al. (2023) and O’Brien et al. (2021) note, action research requires rigorous and constant reflection on the power differentials that exist amongst the stakeholders; such reflection and change necessitates time.

Let us not forget that the hierarchization of knowledge in Latin America that collaborative research attempts to challenge continues to exist today; therefore, we need to generate instances for collaborative and democratic problem solving if we are to one day dismantle the colonial power structures that still exist in the field of education. There are several current research efforts that focus on decolonization of education in Chile, such as Fuenzalida-Rodríguez’ work on the politics of “interculturalidad” (2014), Moses (2020) and her insights into how to decolonize school curriculum, and Ocampo-Gonzalez (2023) and his decolonial discourse analysis on inclusive education. Given this scenario, I believe, as does Brooks (2020), that there is a real opportunity in Chile to expand these efforts into the methodological sphere: participatory methods aims at empowering communities themselves (in this case the classroom) to find their own narratives and trajectories; not under the tutelage of someone seen or perceived as hierarchically superior through the embedded colonial discourse, but in collaboration and through democratization.

Based on those initial conversations with Chilean universities, but mostly through the work done by this project’s participants, I can conclude that there is great potential for community-based, participatory research and that this should occupy a critical place in researchers’ future efforts. Here we can learn from the work done by Ap Sion et al. (2023) in Welsh schools, Chen (2022) with adult education practitioners in England, and Malmström (2023) in Sweden and their collaborative project with teachers as co-researchers; their efforts converge in attempting to democratize research by increasing competencies, eliciting equitable contributions and focusing on research as a generative activity that draws from this collaboration. Chilean trainee teachers are already involved in small-scale Action Research studies as part of their graduation requirements for Education majors on a teaching pathway; therefore, expanding AR into PAR and CPAR would be a logical, coherent expansion and development.