Introduction

This article presents the methodological process of devising a theater workshop and enacting a theater play titled “Amma la” (meaning “mother” in Tibetan) with Tibetan research participants in India. The article details the strategies, methods, and tools used in this endeavor as well as the reflective processes associated with it. This is part of a five-year PhD research project (2015-2020) conducted at a UK-based university and in affiliation with a university based in India. The research explored the embodied experiences of Tibetans living in exile in India, between guests, migrants, and temporary residents with quests for Indian citizenship.

Socio-political context of Tibetans living in India

India hosts the largest number of Tibetan refugees, scattered across 39 settlements (2019). Approximately 80,000 Tibetans have followed the Tibetan religious and political leader, the 14th Dalai Lama, to exile and fled to India since 1959, after China occupied Tibet (Yeh, 2007). The population of Tibetans in India has been estimated to be around 90,000 (CTA, 2017); the most recent figures show 108,000 (UNHCR, 2020), but other sources mention higher numbers, reaching 150,000 (Yeh, 2007). Tibetans living in exile in India have been considered a successful case of a refugee population that has managed to keep their culture and language alive, to reconstitute their institutions in exile, and to create transnational networks (MacPherson et al., 2008). They managed to maintain their identity in exile for 60 years. Recently, the group seems to be positioned between two aims: remaining Tibetan refugees or becoming Indian citizens. In 2010, a 26-year-old young woman won her case for Indian citizenship in the High Court and challenged the Ministry of External Affairs, the first Tibetan to do so.

One of the main arguments regarding the status of Tibetans in India in the literature is that Tibetans remain stateless: India does not legally recognize them as refugees under either international law or its own national laws and it does not enable them to become Indian citizens—with the exception of those born on Indian soil between January 26, 1950, and July 1, 1987 (Tibet Justice Center, 2011, 2016). Tibetans are “guests” in India, residing based on a Registration Card issued to them upon arrival and renewable every year—or every five years since 2014. Reports show that Tibetans have a mixed attitude towards their host country; they are grateful, but feel that their status is marked by impermanence (Gulati, 2015).

In this article, I argue that the performance of the theater play “Amma la,” based on participatory mixed theater methods, tells the experiences of Tibetans living in India in their own words, with imagination and empathy, enacted and performed with skillful engagement. The reflective, relational, and embodied dimensions of performance make “Amma la” a powerful analytical tool to explore not only experiences of migration and citizenship, but also experiences about the human condition: “performance is a prism for studying human life” (Tinius, 2015, para. 1). Through the process of meaning-making that is inherent in drama and performance, participants translate realities and negotiate power structures, thereby informing the development of their own social and cultural identities (Amkpa, 1999). Similarly, a performance group whose name in Greek—Elanadistikanoume—means “Come and see what we do” is made up of people living in Athens without official resident permits or citizenship. Their theatrical performances about the historical pluralities and complexities of Greek society address the growing nationalist and fascist movements in Greece and in Europe while their cultural works are innovative and powerful insofar as they are performed “by those very bodies without citizenship and an official national identity” (Vourloumis, 2014, pp. 241–242). These performances can be understood as an attempt to create a “common front between citizens and noncitizens” (Vourloumis, 2014, p. 242). Hence, I argue that the performance of the theater play “Amma la” by young Tibetans in India in 2019 makes a strong contribution to participatory research about migration, refugees, and citizenship using mixed theater methods in contemporary times.

This article is organized into three parts. In the first part, I explain how and why I interpreted the fieldwork research data (2017) in the form of a theater play titled “Amma la,” an adaptation of the theater play “Waiting for Godot” by Samuel Beckett (1952). In the second part, I situate the play in the literature on ethnography, performance, and theater. In the third part, I continue by presenting the enacting of “Amma la” with young Tibetans in India (2019), at three institutions in Dharamshala: Tibet World (TW), Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA), and the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA). I reflect on these workshops using auto-ethnography and reflective tools that will be discussed at each stage of the process.

Positionality Statement

This article is an excerpt from PhD research completed in 2020, research which was born from a decade-long (2010–2020) academic and personal quest to understand experiences of migration, displacement, refuge, and citizenship. This quest is based on the author’s experiences of living in India at different periods of time, witnessing political movements first-hand, and “becoming” a citizen of India and other countries. I visited India in early 2011 and then moved there after being admitted to an educational institution for an exchange program, during which time I lived in New Delhi for six months. I studied Hindi at the Language Institute for Foreigners in New Delhi while living with an Indian family who became my extended family after I had an Indian wedding. This meant that I was getting an insider’s look into the life of a certain section of society, the upper-middle class, employed in government jobs and living in the center of the capital city, New Delhi. After having secured a job at an NGO in New Delhi in August 2011, but not being granted an employment visa by the Indian Government due to delays in the bureaucratic process, I decided to leave the country and return to living in Budapest, Hungary, where I had lived previously and had completed my MA in Social Anthropology in 2010. However, my scholarly interest in migration and how migrant groups make a life somewhere else was relentlessly on my mind. After 2012, I tried to return to my academic interest in how policies for refugees are made and how people who flee their homes become agents of change. While keeping my academic interest alive, working with NGOs and Research Institutes from Budapest and Germany, and visiting India every year after 2012, I hoped that one day I would be able to go back and study migrants and refugees living in India.

In 2015, I was admitted to a UK-based university to conduct PhD research about migrants and refugees in India, with a case study about Tibetans living in India. Historically perceived as a privileged refugee community, this group has been recently understood as a precarious population living for generations without legal status and is now faced with the possibilities of Indian citizenship which was a very interesting topic for me.

“Start where you are, honor your personal history,” writes Madison (2012, p. 21). Writing about one’s own experiences, both past and present, and about who one is as a unique person, leads to formulating certain questions about the world and about why things are the way they are (Madison, 2012). “Politics alone are incomplete without self-reflection” (Madison, 2012, p. 7), and doing critical ethnography means more than exposing politics. It means acknowledging and writing about the “politics of positionality” (ibid). “Positionality is vital because it forces us to acknowledge our own power, privilege, and biases just as we are denouncing the power structures that surround our subjects” (Madison, 2012, p. 8).

Throughout my PhD fieldwork in India (2016–2019) I reflected on my positionality as a complex identity question and had mixed feelings of outsider and insider based on my knowledge and experience of living in India, my understanding of the Hindi language spoken in large parts of India, my connections to an Indian family, and my Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) status. However, I felt more often like an outsider to the Tibetan communities due to my lack of knowledge of the Tibetan language and preliminary engagements with Tibetan culture, religious, and socio-political life in early 2016. The question of my identity and positionality in the field—and especially my racialized positionality—was recurrent as this is inescapable: we cannot change our place of birth that gives us our racialized identity. However, I came to understand throughout the five-year research process that “fieldwork is intense and interpersonally complicated for everyone. Once you are there, no matter how introduced, it is you—as a person—who develops the relationships you do, even as you never escape your locatedness” (Abu-Lughod, 2016, para. 6) (my own emphasis in italics). This inescapable positionality or locatedness, as Abu-Lughod names it, involves power relations, access to certain places and resources, as well as limitations from accessing certain data.

For instance, I started my fieldwork in 2016 feeling quite naïve and having built fewer relationships in the field with Tibetans, with language limitations. I found myself very new to the Tibetan culture, a foreigner who had some kind of relationship with India through family ties and had lived in the country in 2011, but had none to Tibet—or at least so I thought in the first few weeks of my fieldwork in 2016, which has changed throughout my PhD research. As the research progressed in 2017, 2018, and 2019, I came to develop new relationships with many Tibetan participants and Tibetan institutions in India and developed a new understanding of the people and the places I was researching. I was able to delineate the instances when participants told me what I, as a foreigner, could do to support the Tibetans in India. This included actions like writing about their situation and noting when the research participants enacted issues affecting the community, such as unemployment or alcoholism, during the theater workshops, as these revealed insights that are usually not openly displayed. These reflections were part of the ongoing process of research that included the fieldwork and the analysis, which were linked through carefully considered self-reflexivity and exemplified in this article.

Part I. Live Methods as Performance. “Amma la”: Theater play in two acts

In this section, I present the conceptual and methodological developments that facilitated the interpretation of my PhD fieldwork data (2017) in the form of a theater play entitled “Amma la” which means “mother” in Tibetan. During my second PhD fieldwork in 2017, I employed mobile, multimodal, and sensory methods (O’Neill, 2018) that include the full range of the human senses in exploring the many registers of social life and enable us to produce work that is inclusive of words, images, sound, and text (Back & Puwar, 2012).

In 2017, I conducted ethnographic fieldwork for three months in several locations in India: the capital, New Delhi, which included the Tibetan settlement Majnu ka tilla, McLeod Ganj, and Dharamshala in the Northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh and the Tibetan settlement in Mundgod, in the Southern Indian state of Karnataka.

The theater workshops took place in 2019 in the small town of McLeod Ganj, in upper Dharamsala, which has an elevation of 2,082 m (6,831 feet), in the state of Himachal Pradesh, northern India. McLeod Ganj has a mixed population of more than 10,000 people with many Tibetans born and living here, along with thousands of foreigners visiting this hilly town every year. It is also the headquarters of the Tibetan Government in Exile and has been the residence of the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet, since 1960 (Garbovan, 2019), thus constituting a center for the religious, cultural, and political life of Tibetans in India.

The data collected in all three locations included 21 audio-recorded, individual, group, and walking interviews, and I spoke to more than 50 people during informal conversations. After returning from fieldwork, I transcribed the audio-recorded interviews, paying attention to the non-verbal language, such as pauses, silences, laughter, tone of voice, background sounds of rain, cows, dogs, traffic, music, and conversations taking place at the same time in multiple languages (Tibetan, Hindi, English). All these forms of expression are important as they reveal emotions, intentions, meanings, and context and constitute “live methods” (Back & Puwar, 2012). The innovative approaches to methods (Back & Puwar, 2012) engage words, images, text and sounds while allowing space for flexibility, changes, and contingency and these methods include walking tours and experimenting with ambulant techniques, such as ambulant interviews (Back, 2012). These experiences aim to make space for the co-existence of a multitude of senses and allow their representation in the research process. They also offer new ways of capturing voice, beyond the transcribal voice, as there can be discordant voices, visions, and feelings within an epistemology that is multisensual and multiperspectival and includes sounds, touch, and taste, instead of privileging speech and images (Denzin, 1997, p. 36). This type of ethnographic data can then be used to support an interpretation using creative means such as arts, theater, ethnographic performance, and ethnopoetry (ASA, 2018; Jones, 2018).

After returning from India in 2017, I transcribed the interviews (which were conducted in English and Tibetan) with the help of a Tibetan-English interpreter. The interviews were then translated to only English and I analyzed the data with the help of MAXQDA software. I used coding techniques, deriving codes from the interviews in a deductive approach, that produced key themes, employing a researcher’s version of grounded theory methodology (Birks & Mills, 2015; Saldana, 2011).

When I completed the data analysis, I tried to make sense of the data and thought about presentations that would be inclusive of the sounds, images, and voices I had heard and seen during the fieldwork. I chose to espouse the use of live methods during the fieldwork research with creative means of presenting and communicating the data in the form of a performance. This resulted in a short theater play titled “Amma la.” The play is an adaptation of Samuel Beckett’s drama “Waiting for Godot” (2004), first published in 1952 and considered to be an innovation in the theater of the absurd. It is important to mention that the data interpretation presented in the play “Amma la” did not follow the content of the original play “Waiting for Godot,” nor the description of its main characters, who are of questionable social status. However, the structure of the play “Amma la,” the props, and its theme—a seemingly endless wait for something or someone—could be considered an adaption or appropriation of Beckett’s play. “Waiting for Godot” has been staged in numerous locations since its original production: Sarajevo, South Africa, Avignon, New Orleans, and London. In each place, it acquired new meanings and interpretations about human existence, oppression, nobility, and absurdity in a metaphorical theater where “Godot can be anything you want” (Smith, 2009). What is important to note is that in both plays, the characters wait for something, or someone, by a lonely tree in a world where time, place, and memory are blurred and meaning is where you find it. The playscript of “Amma la” is available as a supplementary material to this paper. The playscript was published in another academic article in the Irish Journal of Anthropology (Garbovan, 2019).

The play “Amma la” was performed in July 2019 in McLeod Ganj, Dharamshala, by 70 participants during three theater workshops. The Tibetan participants at TIPA and LTWA came from diverse social and educational background and from different parts of India. The students at TIPA were between 16–21 years old and were selected by a committee to represent each Tibetan settlement across India. The performances were expressive of participants’ own views and understandings but arguably also of the experiences of their families and communities whom they have lived with and observed during their lives. The students at the LTWA were 20–35 years old, and included monks and nuns along with lay young men and young women, and they studied different subjects, such as literature, design, marketing, IT, or Buddhism. The same could be argued about their performances: they were most likely inspired by their personal experiences from the middle of Tibetan and non-Tibetan communities.

The participants did not receive any compensation, monetary or otherwise, for their participation in and their performances of the “Amma la” theater workshops, since the workshops were designed as a result of an invitation to organize the workshops at two of the institutions (TIPA and TLTWA) whose students were registered on their courses. The third institution, TW NGO, was a place where young Tibetans would come regularly to attend trainings and workshops and compensation of the participants was not a regular practice at the NGO. However, the author paid a nominal fee to book the room of the TW NGO where the first workshop took place.

Part II. Mixed theater approaches. Situating “Amma la” in the literature on ethnography, performance, and theater

I argue that the performance of the theater play “Amma la” in McLeod Ganj, Dharamshala, in July 2019 sits theoretically and methodologically at the intersection of performance ethnography (Anderson, 2007; Denzin, 2003; Flynn & Tinius, 2015), verbatim theater (Paget, 1987) and political theater (Lustgarten, 2015), and participatory drama (Brown et al., 2017). The devising and 2019 performance of the play also borrows from ethnotheater and ethnodrama (Saldana, 2011; Turner, 1982). It could also be argued that the play constitutes a form of experimental theater within performance ethnography (Gatt, 2015) that is not complete and foreclosing, but processual and prospective. And, finally, performing “Amma la” is a form of process drama (Bowell & Heap, 2013) and applied drama (Amkpa, 2014), focusing on improvisation (Vourloumis, 2014), and the process of creating and acting a scene for the benefit of the participants-actors, and not on the polished and rehearsed performances for a specific audience. For these reasons, I argue that “Amma la” is constructed and theoretically supported by what I will simply call “mixed theater approaches to research,” or “mixed theater methods.”[1]

Performed ethnography or ethnodrama is considered an applied method of performance ethnography and has been used for representing and disseminating research data “with the potential to engage diverse audiences with the research in ways that are empathic, emotional, and embodied as well as intellectual” (Given, 2008). Performance ethnography was pioneered by Victor Turner (1982) as a research methodology and is considered a staged re-enactment of fieldwork notes taken during ethnographic research (Anderson, 2007). One of the key elements of performance ethnography is “the power to engage and at some level to move an audience” (Anderson, 2007, p. 80). Victor Turner also coined the concept of ethno-drama, a compound word created by “ethnography” and “drama” (Saldana, 2010). Ethno-drama is the written playscript or screenplay composed of dramatized selections of narrative collected from interview transcripts, participant observation field notes, diary entries, social media, email correspondence, and newspaper articles (Saldana, 2018). Ethno-theater uses fieldwork notes for theatrical productions (Saldana, 2018). Ethno-drama combines critical ethnography with performance to construct a new form of theater that aims to translate action research into reflexive performances and uses interactional theater to construct meaning and understanding with the participants (Mienczakowski & Morgan, 2015). The difference between the two concepts mainly resides in their historical origins and the ways they have been interpreted over the years (Anderson, 2007).

Similarly, the concept of verbatim theater typically represents the voices of marginalized groups through their own words (Anderson, 2007). Verbatim theater is a “category of staged performance in which the actual words of real people are edited into a script and performed on stage by actors” (Long, 2015, p. 305). Traditionally, a team of actors assisted in the development of verbatim theater performances by collecting and then performing the interviews (Anderson, 2007). Long (2015) argues that verbatim theater is a response to the frustrations and difficulties faced by researchers in communicating “the atmospheres and complex characters met in the fieldwork” via the established means of disseminating ethnographic findings: text and film (Long, 2015, p. 306).

In a similar way, Zagaria (2016) found the tools of film and text to be inappropriate for conveying the impressions gathered during her fieldwork on the island of Lampedusa in 2011 to audiences within and beyond academia. She then returned to the island in 2013 with several theater makers from the School of Physical Theater Jacques Lecoq, to carry out a month of collaborative fieldwork research and to develop a performance about life, death, and migration on this island. The theater show “Miraculi” was performed by Zagaria’s team in 2014 in front of a local audience in Lampedusa, as explained in her work:

We came up with characters by mixing stories and traits belonging to different people we had met while in Lampedusa, aiming to preserve their anonymity by creating fictional persons that were nevertheless drawn from the real life stories we had collected. (Zagaria, 2016, p. 21)

In a similar fashion “Miraculi,” the 2019 performance of “Amma la” is a representation and interpretation of the PhD ethnographic data. In this sense, it can be considered as ethno-drama and performance ethnography. Furthermore, the “Amma la” performances relate to broader ideas about knowledge, arts, the purpose of performance and theater, and how this could help us “build our future, instead of just waiting for it” since “theater is a form of knowledge; it should and can also be a means of transforming society” (Boal, 2002, p. 16). In this sense, “Amma la” represents a form of political theater (Lustgarten, 2015), with an emphasis on agency and hope: “theater is as a means for reviving hope” (De Michelis, 2017, p. 11). The performances connect with participatory and process drama which are improvised in nature and position participants as “co-creators of the dramatic experience as well as the audience for their own work” (Bowell & Heap, 2013, p. 5). This reveals how using drama to share the research findings is a meaningful and powerful tool that brings together researchers and participants in a transformative process.

By interpreting the ethnographic data in the form of the theater play “Amma la” (2019)—as well as its performance by Tibetan participants in India—I aim to convey and share the research findings beyond academic audiences and, more importantly, open the space for reflection, collaboration, and embodied and creative enactments of non-binary narratives. I used participatory theater approaches as an exploration of alternative forms through which to convey, present, and allow for contestation, negotiation and re-creation of ethnographic knowledges which have the potential to provide new understandings of “incompleteness, the ongoing, not-yet human experience” (Gatt, 2015, p. 349).

The performances by Tibetan volunteers, students, and non-actors offered an avenue for addressing issues of interpretation and representation due to the immediacy and the possibility of “answering back” inherent in performance, and thus can make space for subaltern knowledges, and new insights into forms of reflexivity that are not reduced to a mind/body dichotomy (Gatt, 2015, p. 335). Drama, in its performative sense, has been understood as a space for creating “symbolic interpretations of social reality” (Amkpa, 1999, p. 6). In this case, the space for innovation, re-interpretation, and creativity in the performance remained completely open. The volunteers-turned-actors could choose what to do with the playscript given to them, how to use it, which words to speak and which ones to replace, which language to use (at times they used more than one), and they decided on how much meaning and importance which part of the playscript had. In some cases, the sounds and gestures became more important than the spoken words. This is summarized for each performing group at each institution in Appendix 1 (Table with structure and presentation of “Amma la” data by characters, props, dialogue, and languages used).

For instance, the topic of unemployment was enacted in the performances of Group 3 at LTWA and Group 7 at LTWA with new implications. In this performance, Namgyal (one of the main characters) is a drug addict and alcoholic, thus by implication unemployed, who is saved only by returning to Buddhism and becoming a monk in the enactment of Group 3. And Tenzin is the young man who sits idle and smokes in the Tibetan settlement, again suggesting he had no work, in the performance of Group 7 at LTWA. These performances both constitute novel and creative interpretations, as the Tibetan participants-actors decided to do away with the provided script and introduced innovative interpretations that highlight the lived realities of Tibetans in India.

Unemployment in the Tibetan community in India, especially amongst the youth, is an important discussion in the current literature. Between 1998 and 2008, the number of jobseekers amongst Tibetans in India increased by 103.7%, with 17% in the underemployed/unemployed category (Gupta, 2019). This is due to several factors, including the fact that Tibetan youth are well educated and are looking for opportunities to match their skills, which cannot be found in the Tibetan settlements where the work focuses on agriculture and sweater selling. Job opportunities and higher incomes are typically found in large Indian cities where the competition is fierce. As non-citizens of India with temporary identity documents that must be periodically renewed, Tibetans are at a disadvantage in private sector jobs that may also require travel. Additionally, many Indian Government jobs are unavailable to non-citizens (Gupta, 2019, p. 342).

In another example, I highlight how bringing characters alive and naming them enhances the innovative dimension of the performances and supports the artistic, collaborative, and interpretive framework that theater approaches add to research. For instance, the characters of the soldiers whom Amma la mentions when she talks about how she fought in the Tibetan regiment 22 of the Indian Army come alive in the performance of Group 2 at TIPA. They are enacted by three teenage boys who stand in one corner of the room, lifting weights and doing exercises, and a fourth one enacts the role of their leader/instructor, while Amma la and Tenzin perform the verbatim playscript.

Different performances brought different characters to the forefront. For example, the role of the neighbor, Karma la, who goes to Manali to sell sweaters, comes alive in the performances of Group 6 at TIPA and Group 5 at LTWA, while her daughter comes alive in the performance of Group 7 at LTWA. The character of the cook, who is talked about in the dialogue between Amma la and Tenzin in the original script also comes alive in the performance of Group 7 at TIPA. This character is enacted by a young woman in this group who comes to the house of Amma la and starts chopping real grass and vegetables and enacts washing them. In the performance of Group 6 at TIPA, the friend of Tenzin, who is mentioned in the playscript in passing, a young woman who obtained a new job in New Delhi as a nurse, becomes a visible and present character in the performance of Group 6 at TIPA. She plays a brief role, serving tea to Amma la and her character.

Part III. Devising the theater workshops “Amma la” in India

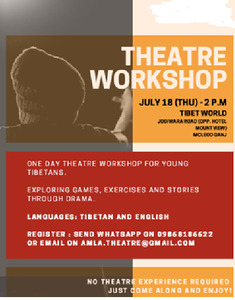

When I arrived in India during the first week of July 2019, I contacted the research participants I have known since my previous fieldwork trips in 2016 and 2017 and invited them to join my upcoming theater workshop in McLeod Ganj, although I understood that those who lived in New Delhi, Shimla, and Mundgod would likely not be able to join. I met with the Director of the NGO Tibet World (TW) on the first day I reached McLeod Ganj, after an email exchange the previous week. We discussed my PhD work and my previous trips to McLeod and the volunteering period at the NGO and I asked him about his work. He kindly allowed me to use one of the available rooms in the NGO TW for the theater workshop and advised me to organize the theater workshop at the end of the week, on Thursday or Friday, July 18-19. He also advised me to place an informative flyer in town and online and to add an email address and phone number for people to register. Meanwhile my partner, who was in the UK, helped me prepare a flyer about the theater workshop (Figure 1).

Following that advice, I asked my partner to create another email address for this purpose: amla.theater@gmail.com. I printed 20 copies of the flyer and distributed them around McLeod Ganj, after gaining the permission of the people who owned or managed some of these places: at several Tibetan restaurants, cafes and hotels, in a tattoo and piercing shop, at the Tibetan Career office, the Students for Free Tibet Office, in two bookshops, and at the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA) in addition to directly distributing them to my Tibetan contacts.

An interesting development took place after I had met the Director of TW and went out in town to distribute the flyers. During distribution, I walked up to the TIPA office in McLeod Ganj and left a flyer with the Tibetan officer there, to invite the TIPA students and artists to come along to the workshop at TW on Thursday, although I did not feel very sure about it, as noted in the fieldwork diary:

I was not very confident or assertive in what I was saying, maybe because I had this idea that the place (TIPA) is famous and reputed and I did not think they would actually be interested, I guess I also felt a little shy. (Fieldwork diary entry, 17 July 2019)

The Tibetan officer informed me that their students usually do not go to TW and their artists were in the USA on a tour. But he asked me instead if I would like to offer a separate theater workshop to the TIPA students, on another day. I said yes, although I was amazed to hear that and did not know what they expected to see. Finally, he spoke to another officer and they invited me to run a theater Workshop at TIPA on Friday, July 19. On the evening of the same day, I received a confirmation email from the Tibetan officer at TIPA who invited me to do a separate theater workshop for the TIPA students, on Friday, July 19. He asked me not to bring any students from TW and he created another flyer about the TIPA workshop, which he planned to distribute to their students (Figure 2).

The same evening, I received a text message on my Indian phone number from an unknown number. The SMS (Figure 3) was sent by the English teacher at the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA) who saw the poster about the theater workshop in town and she asked me to provide a drama workshop to her Tibetan students at LTWA. I responded to her surprise invitation and we agreed to meet after the theater workshop at TW, on July 18.

First theater workshop: Tibet World (TW), McLeod Ganj

In advance of this first workshop at TW, I prepared a list of games, exercises, and short story-based drama sessions from a variety of events that I attended in the UK and based on selected online resources about Forum Theater (Boal, 2002), Physical Theater (Callery, 2002; Lecoq, 2001), as well as literature recommended by theater practitioners I have met during my trainings in London, during the preparatory six months period in the UK (available as Supplementary material File 2 and File 3). In physical theater, Callery (2002) and Lecoq (2001) place crucial emphasis on the meaning of the body and the practices for preparing the body before performing any acts. According to Callery (2002), physical training is a process that leads to creative freedom and not a way of following prescriptive techniques. It is a “process of self-discovery and a time necessary for the actors to practice skills, to develop and explore performance potential” (Callery, 2002, p. 19). I printed a list of games and exercises used in theatre workshops and took it with me to the first theatre workshop at TW on 18 July. The theatre games, non-verbal activities and the exercise are described in the Supplementary materials File 3.

The theater workshop at the TW on July 18 started about 20 minutes late with 12 participants, most of them young men in their 20s, along with two Tibetan teenagers and a young woman from France who was a volunteer from Tibet World. Another Tibetan young man had a camera given by TW and took photos and videos after I had received the students’ consent. One of the participants, whom I will call Sonam, offered to be an interpreter given my lack of fluency in Tibetan language. Although all but one of the participants said they did not need interpretation, having Sonam was helpful, as I felt it was good to have someone to help me organize the games. In the second part of the workshop, I asked for his advice about how to do the theater performance. He read the playscript and offered to translate it from English to Tibetan if necessary (Figure 4.

We went through all the preparatory games and image theater with the 12 Tibetan participants, as shown in Figure 5. This activity lasted for about one hour.

After the preparatory sessions, I invited the groups to enact a short story; each group decided on a story and then worked together and used gestures, frozen images, and words, if they wished, to enact the story. Each group had 10-15 minutes to practice, and they laughed while practicing, which they did with the games, too.

Participants seemed to enjoy the warm-up exercises and the short story and I thought it was a good preparation for performing the play. This part of the workshop ended around 3:45 p.m. and I was worried that we had just 15 minutes left to do the play “Amma la”—I was not sure how to accomplish it in such a short time. Then, the Director of the NGO came and told me we could stay for another hour and continue the workshop. I was happy to hear that, but all the students had to excuse themselves and left at 4 p.m. for another class. Only my interpreter who stayed longer, and during our chat he told me about his work in the Tibetan community in another town and about his sisters who lived abroad.

Reflections on an unfinished workshop

On reflection, in this first workshop I learned how to manage my time and organize the workshop better in the future. I felt responsible for this unfinished workshop, but I realized it was fun but incomplete from the point of view of my research, as we did not perform “Amma la.” One option could have been to continue with the performance the next day, but I had two more workshops planned. Finally, I decided to move ahead and organize the next two workshops at the TIPA and the LTWA with the new groups of students. By this time, with the lessons learned from the first theater workshop at TW, I knew that I had to reorganize the workshop and allocate one hour for preparation and one hour for the performance of “Amma la.”

I was also considering how to do the performance with a large group of 35 students. Ultimately, I decided to divide each group in seven smaller groups with five participants each and, correspondingly, to divide “Amma la” into seven sections (Figure 6). This proved to be a useful strategy that worked well in the remaining two workshops, asdiscussed below.

The second theater workshop: TIPA, McLeod Ganj

The Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA), in Dharamshala, was established by the 14th Dalai Lama in 1959 as the first Tibetan institution in exile. TIPA is the preserver of the folk opera of Tibet, called “Ache Lhamo,” and of a wide repertoire of musical, dance, and theatrical traditions from Tibet. TIPA also hosts a modern theater troupe that performs contemporary Tibetan plays and the institute has workshops for making costumes, masks, and musical instruments, while it trains young Tibetans to become teachers of Tibetan music and the performing arts at Tibetan schools and settlements throughout India and Nepal (TIPA Biography).

In 2019, TIPA celebrated 60 years of life and work in exile in India, preserving and promoting Tibetan musical heritage, folk music, opera and dance traditions of Tibet. The 60 years milestone was celebrated by TIPA artists, performers, and CTA officials in October 2019 with a showcase by Tibetan exile artists, who performed Tibetan dances, songs, and Tibetan opera as shown in Figure 7.

At the time of my third PhD fieldwork in India, in July 2019, the Tibetan officer who invited me to do the theatre workshop at TIPA informed me that the main hall or auditorium where TIPA artists have their performances was under construction and it would be ready by October, when a large celebration would take place. This was indeed the 60-year celebration of TIPA in exile, as briefly presented above, and I read about it in November, when I was already back to the UK and thus I could not attend this event, had I been invited.

On July 19, 2019, when I had to facilitate the theater workshop at TIPA, I had mixed feelings about what I was doing and tried to gather feedback on my work, from both the participants and the Tibetan officer who invited me, especially after the workshop ended. My mixed feelings had to do with the place where I was going to do the workshop, the number of students who were going to participate, and the expectations that I had to manage, which were two-sided. On the one hand, I expected the theater workshop to work very well for my PhD, and better than the previous one, at TW, where we ran out of time. Secondly, I did not know what the Tibetan officer who invited me to TIPA and the TIPA students expected out of the theatre workshop, and I found myself thinking that I was not an expert and felt like an impostor. “The impostor phenomenon” or “impostor syndrome” was described as having strong feelings of deceit, dishonesty, and self-doubt in the face of success (John, 2019). The phenomenon describes how many high-achieving women doubt the expertise they have in their own field and feel they have made others believe that they are more capable than they truly are (John, 2019). It has also been argued that women and ethnic minorities tend to experience impostor syndrome more, partly due to structural inequalities and imbedded forms of sexism and racism (Buckland, 2017). I felt strongly connected to these arguments as a woman coming from a mixed ethnic background, born in Europe, studying in the UK, with another side of family living in India and doing research about Tibetans as a refugee group living in Indian and recently having the possibility of becoming Indian citizens, thus also becoming ethnic minorities in the country.

My feelings about being unfit to conduct a theater workshop at this institute partly originated in existing knowledge about the TIPA: a famous and prestigious place where Tibetan artists and experts in the field of arts live and work—and where I did not feel that I belonged or have had any experience with. My mixed feelings about doing a workshop at TIPA were reinforced later, when I returned from the fieldwork and met with my Tibetan friend and interpreter in the UK who helped me translate some of the videos from Tibetan to English. He told me that he was surprised that the TIPA students were part of my workshop, as they are not easy to find, always abroad, and difficult to have them part of any workshop (Post-fieldwork diary, 16 October 2019).

Nonetheless, on the day of the theater workshop at TIPA, I felt confident about the first part: the games, which I had practiced the day before with the students at Tibet World. And I had spent a considerable amount of time preparing for the workshop the day before, going through some of my PhD chapters about Live Methods and several more articles on theater.

On the day of the TIPA workshop, when the young Tibetans entered the hall at TIPA it felt good to see them as they reminded me of teaching at my UK University, in a classroom of 35 students. They looked very young and the Tibetan officer later that day told me their ages ranged from 16 to 21. The group was evenly split between girls and boys, all of whom looked energetic, confident, and excited. At the start of the workshop, the Tibetan officer introduced me briefly in Tibetan. When I introduced myself, I discussed my PhD about Tibetans living in India, my studies in sociology and anthropology, and the more recent training I had in the UK in drama and theater. I told the students that we would do games and exercises during the workshop, and then enact a story. Then we started playing the preparatory games and I was slightly worried about how to work with such a big group, so planned to do only the games I felt were suitable for a group of 35, including the frozen image game (Figure 8 below) and enacted animals (Figure 9).

We then played three games in pairs and finally the game about the animal figure again with the entire group, which they enjoyed and laughed a lot at (Figure 9). We played all the games for about 30 minutes, spent another 15 minutes enacting frozen images and various feelings, and then moved into the story part. I asked the students to tell me the parts of a story and they answered quickly, without feeling shy, naming several elements, such as characters, emotions, drama, focus, and narrator as I was wrote their responses on the whiteboard.

We started the second part of the workshop, where the students had to enact the theater play “Amma la,” at 2 p.m. and had one hour left in the workshop. I divided the students into seven groups and gave each one section of the playscript and asked them to discuss in their groups and prepare for the performance, with a time limit of 20 minutes. I checked on each group several times and answered their questions, and also confirmed that they understood the English playscript. They all said yes, in line with what the Tibetan officer told me at the start of the workshop: that all the students had good English speaking and reading skills and there was no need for a translator. One group asked me early on if they could enact the play in Tibetan language, instead of English, and I said yes, of course: the participants could decide which language to use during the performance.

During preparation, the groups talked a lot with each other, but I gently pushed them towards practice and performance in their groups based on my own experience with drama workshops, where the theater practitioner told us to spend less time talking and more time standing up enacting the playscript. I noticed that the students were skilled and creative during their preparation time, as some of them practiced the movements and sounds of a cobra, a cow and a dog, while others collected grass and started cutting it with a knife, and still others cut paper into smaller pieces and asked me to write the symbol of foreign currency: EUR and dollar (Figure 10).

The performances of the students at TIPA made a strong impression on me, as noted in the Fieldwork diary, the evening after the theater Workshop:

The levels of confidence, creativity, talent, and imagination they used baffled me, I was in utter amazement. All the groups improvised, they learnt the dialogues by heart in the thirty minutes they had to prepare, and they acted without feeling shy or scared, they did not even look nervous! … I thought it was fantastic! Each group prepared a scene – using tables, chairs, papers, a scarf, a door, empty cups to drink tea from, and changing the setting every time before their turn came to perform (Fieldwork diary entry, 19 July 2019).

Post-performance reflections on performative and embodied knowledges

At the end of the TIPA workshop, I chatted with the Tibetan officer who invited me and asked for his feedback. During the workshop he was taking photos and was smiling and laughing with the students, especially during the games, which I was happy to see. He then made videos of their performances, to save them on the online archives of TIPA and share them with me, which was a great help.

The Tibetan officer told me that he did not know much about the theater workshop in advance, until I made the introduction on the day, but it was alright in the end. I told him how impressed I was with the students’ acting skills, their talent and energy and creativity. He shared that students study at TIPA for four to five years, but they continue afterward for up to 11 years. Some of them then become senior artists and perform at events in India and abroad, while others become teachers of Tibetan music and dance in Tibetan schools in India. The students were selected from all the Tibetan settlements in India based on an exam by a selection committee. He also told me they had someone from Germany who came to do a drama workshop in 2018. In the photos and video recordings he showed me while we were waiting for the theatre workshop’s files to upload, I could see some wonderful drama performances, with actors on a beautiful stage, wearing costumes, wigs, masks and he told me they were the TIPA senior artists, also the younger ones were dancing and playing some of the instruments. At that point I started feeling that the students were so talented and it was a loss that I did not have the nice stage and auditorium nor the costumes to do a drama, like in the videos from their last year’s performance.

While I was wondering what the students thought of the theater workshop, and whether it was too simple for their level, I watched out the window and saw the same students performing a traditional Tibetan dance and singing together in Tibetan on an improvised stage in the courtyard, among the construction work going on and street dogs sitting patiently and watching them performing. Their performance was beautiful. I was captivated and and went out on the balcony and watched for another 15 minutes, while officer was transferring photos to me. At that time, I felt that these young students were real artists and that I would love to do something similar, artistic, and beautiful in my own life. I began to understand that I could learn from and be inspired by them, and their acting skills during the play were all part of their talent and skills. I was wondering how they invited me to teach them when I was not an artist as such, but rather an academic using theater methods. I still could not know their thoughts about the theater workshop, but I started to understand that my presence there and the theater workshop I facilitated was, in fact, a co-production of artistic, performative, and embodied knowledge about Tibetan lives in exile in India. More than that, it was a time and space of shared learning, shared experiences and understandings, collaboration, and reflections on the human condition, where the researcher is a learner herself and the participants-students-actors kindly introduce her to new meanings, ideas, and potential. This constituted a disrupting act to the traditional methodologies and epistemologies of knowledge production, as Gatt (2015) writes:

Academic knowledge and epistemology privilege the mind and the intellectual forms of knowledge over other forms that are considered practical. We need ways of working that promote different ways of knowing, different methods that transcend the old epistemologies and ontologies and different understandings of personhood. (Gatt, 2015, p. 343)

This reflection and argument support the use of participatory and performance-based methodologies as alternatives to the way knowledge is produced and represented, especially in Western-dominated understandings of the world, where the written text is considered more valuable than bodily expression (Madison, 2012). By using performance and ethnography and co-producing knowledge with the participants, this research forged a better understanding of reflexivity and collaboration and acknowledged the inherent temporality of knowledge (Gatt, 2015). This form of embodied, co-produced knowledge shows how this research contributes to decolonizing research and how in the process of co-producing research and sharing spaces of co-learning, common experiences and understandings with the participants, researcher’s identities become reshaped and transformed (Keikelame & Swartz, 2019).

The third theater workshop at LTWA, Dharamshala

In advance of the third theater workshop at LTWA, on July 18 2019, I met with the English teacher who invited me to run the workshop. Using the experience I had gathered at the first workshop, I showed her the preparatory games, and she advised on what we could do with the students at the Tibetan Library and a few things that may not work. I also explained to her that the play was an interpretation of my PhD research findings, and how it could be enacted by her students. She told me that the group was made of 35 Tibetans, mostly lay people, with a few monks, one from Vietnam and one from Bhutan, with different levels of English proficiency. She was excited about the workshop and told me that she invited me to do a drama workshop because she wanted her students to build confidence, express themselves more freely (especially in English), and get to know each other and have fun. We agreed on holding the workshop on Saturday, July 20, for two hours, but that we would not need a translator.

On the day of the LTWA workshop, I entered a small classroom with 33 students on the second floor of the beautiful building of the Tibetan Library, and I felt more confident than in the previous two workshops, perhaps due to the experience I had gathered in the past few days. However, I also felt that we had less space for the games and performance. Nevertheless, I was hopeful and confident, and the impostor syndrome started to fade away.

The students at the Tibetan Library were indeed a mix of monks, nuns, and lay people, all of whom were young. The teacher told me they were between 25 and 35, and had different backgrounds. For example, some had studied commerce, architecture, design, IT, English literature, and Buddhism before joining the translation course. She briefly introduced me and then I said a few things about myself, about my PhD about Tibetans in India, and my experience with theatre and drama. I also talked about the structure of the day. We did all the games as in the TIPA workshop, but this time enacting an animal game did not work that well, either because the students were shy, or they had less space, or both. But otherwise, they had fun with the games and the teacher was pleased to see that. As agreed with the students, the teacher took some photos during the workshop.

When I introduced the theater play “Amma la,” I told the students that this was part of my PhD research and although it was written in English, it was about Tibetans in India. And since they studied translation, they would be the most suitable to translate the story in Tibetan for themselves and the group they were working in. Before we enacted the play, I asked them about the constitutive elements of a story; they were all quick to answer and came up with great ideas that I wrote on the whiteboard (Figure 11). I told them that all or some of the elements they mentioned were present in the play. Interestingly, the students had named the element of a narrator and subsequently, during their performances, almost all the groups featured a narrator, which I did not expect to see, but it was part of their creativity and skills.

After the ten minutes’ tea break, I divided the students into seven groups and gave each a short text, a piece of paper cut from the playtext “Amma la,” just like with the TIPA students, but this time I added an extra note to each group: the introduction that sets the scene and the two characters. Then I went around to each group to see if they had any questions. Before that I told them to use their imagination and creativity to enact the story and to use Tibetan language and/or English, and they took around 30–40 minutes to prepare for the performance (Figure 12).

Many of the groups asked me how they would enact the play with only two characters but five people in the group. I told them to identify more people in the dialogue, by their names or occupations, or to identify animals or sounds. I also explained that they could have more or less dialogue, create new characters, use both languages, and do as they wished. And indeed, when the time came for each group to perform, I was amazed at their display of creativity, improvisation, and imagination.

We ended the theater workshop after the last group performed the story and the English teacher said a few final words, thanking me for my work, which I felt humble and happy about. I said a few sentences filled with appreciation and praise for the students’ performances and their creativity to choose what to do with the story, which language to use, how closely to follow the playtext, and how to change it. I thanked their teacher for having invited me and wished them good luck with their studies and then left. A heavy storm marked the end of the day and the fieldwork week in Dharamshala.

Post-Performance Reflections on Improvisation and Intersectionality

The performances enacted during the theater workshops helped me reflect on the importance of two key concepts: improvisation and intersectionality, and how they applied to this research. First, the theater workshops reveal the importance of improvisation and exploration of ideas and feelings in research using applied drama, that replaced the rehearsing and preparing a polished performance for an audience. This has been emphasized in other contexts, for instance applied theater work in South Africa (Chatikobo & Low, 2015) shows that having no trained actors performing might work better since the enactment is “about play, being playful and creatively collaborating” (Chatikobo & Low, 2015, p. 383). Moreover, in the same context the researchers emphasized the importance of not relying on a model or formula of applied practice, but they rather decided to work in a way which was responsive to who was in that space. “Such an approach also enables different ideas to emerge, ones which perhaps were not in the original plan” (Chatikobo & Low, 2015, p. 383).

In a similar manner, Vourloumis (2014) wrote about how improvisational practices are necessary for articulating and shaping the performances of the non-citizens’ group “Come and see what we do”/Elanadistikanoume, whose work was devised by experiment and collaboration. Vourloumis (2014) then argued that these improvisations were important as they promoted inclusiveness for everyone, including non-trained children, and they showed how such a politics of performativity could reveal “other ways of being in the world” (Vourloumis, 2014, p. 249).

I argue that these understandings of applied theater and drama selected from other types of research correspond to the performances of the non-trained student-volunteers in the theater workshop in India (July 2019). Their spontaneity and imagination sparked my curiosity but also answered my worries about how the performances could be enacted without having trained actors and repeated rehearsals. In Madison’s (2012) words, human beings are a naturally performing species, rather than homo sapiens, we are homo performans (pp. 165) and here lies the power of performance.

Secondly, I reflect on a contextually applied understanding of the concept intersectionality. Below, I show how the performances of the research participants in the theater workshops and their enactment of “Amma la” constitute an intersectional exploration of their different age, gender, education, religion, and geography-based identities. More than that, it denotes an intersectional understanding of their experiences of living in India that shape and are shaped by these identity categories. The workshop participants at all the three locations were young Tibetans with some level of education who spoke or understood English. This means that I did not include Tibetans of middle or older ages, who had less educational qualifications and who did not speak or understand English, in the workshops. Still, I emphasize the fact that the playscript of “Amma la” was built on the interpretation of the research findings from the 2017 PhD fieldwork, when I met with, interviewed, and was inspired by Tibetans of all ages, with or without education and formal qualifications, who were born in Tibet or India or Nepal. I also argue that one of the main characters in the play was an older Tibetan lady and her role was enacted by different people during the theater workshops in Dharamshala, including a 35-year-old Tibetan monk and several young Tibetan women.

For instance, the character of Amma la is enacted by young women in all the performances except in Group 1 at LTWA, where it is played by a monk, who walks slowly, wearing his monk robe that covers his head, miming back pain and holding an imaginary stick in her/his hand. This gender switch was a decision made by Group 1 at their own initiative and shows how the Tibetan participants co-created the performances with imagination and creativity but also reflect current political ideas about the identity, composition, and representation of Tibetan life in India, where the role played by the monastic community remains very important (Tanaka, 1997). The monastic community helps preserving Buddhist traditions and religious practices, but they also hold seats in the Tibetan Legislature. The four schools of Tibetan Buddhism and the traditional Bon faith elect two members each in the Tibetan Parliament in exile (Tibet.net, 2020).

In another example of performing identity in creative ways, Group 2 at LTWA decided to have a monk play the role of a tree. The Tibetan monk adopts a non-human position or a possibly neutral character in this performance, he enacts a tree standing with his hands lifted vertically. This could mean offering protection and shade to the other characters and, overall, enriches the matrix of social identities at play in this group’s performance. Long (2015) writes about how audiences and actors identify affectively with characters in a matrix of social relations that include class and gender, and I would add religious identity to Long’s list.

The role of the tree is very different in the performance of Group 4 at LTWA. There are two trees in this performance, whose roles are enacted by a young woman and by a monk, respectively. The monk enacting the first tree in this group plays a very active role by the movements of his body, without any dialogues. He puts his robe on both his arms and he stretches them up, like the wings of a bird, and the robe covers his face. He also frequently moves his arms above the two sitting characters, like dancing, and these movements send the audience into loud and relentless laughter. The narrator and the young woman enacting the second tree try to restrict the movements of the “first tree,” by gently touching his arm, to no avail.

The viscerality of this performance is fascinating and represents a mode of performance that pursues storytelling or drama through physical means, where the physical and visual aspects of the performance are at least as important as the dialogue. This corresponds to a form of physical theater (Bailey, 2019; Callery, 2002; Lecoq, 2001; Zagaria, 2016). “In physical theater, the primary means of creation occur rather through the body, than through the mind. In this form of theater, the spoken word is considered as just one element of the performance” (Callery, 2002, p. 4).

These elements of a theatrical play, such as mime, acrobatics, mask, commedia, dance, or visual theater that go beyond the written text are also defined as “theatricality,” and the non-textual often becomes more important than the language (Grammatikopoulu, 2017). Therefore, I highlight how this performance added a new dimension of creativity to the reinterpretation of the play, by focusing on the physical, visual, and bodily elements, while keeping the text of the playscript unchanged. It also shows how the written word, which is prioritized in Western academic knowledge over bodily expression (Madison, 2012), can become less important in a theatrical play where the participants decide that non-textual elements such as a dancing tree can take the central role.

Overall, the reflections and analysis of the Tibetan performances during the three theater workshops in Dharamshala, India, show that the author as facilitator was getting more confident and refined the workshops. Similarly, there was also progression in how the participant-actors performed. This could be explained through the lens of a contextual understanding of how this participatory method enabled a progressive co-learning process: both the author and participants learned from each other in creative and imaginative ways through performances of mixed theater methods.

I argue that the performances enacted by the Tibetan participants in the “Amma la” theater play (2019) also show a contextualized and time-based understanding and meaning of identity and participation in the life of the Tibetan community in India in 2019. These performances, if enacted elsewhere (for instance with Tibetans living in the UK or any other country), would be enactments of those places, identities, subjectivities, and memories. Therefore, the use of participatory mixed theater methods to share research findings and co-create knowledge with non-trained, volunteer-performers highlights its important contribution to co-learning in “cultural spaces” and to connecting with discourses in which the writer, the performer, the reader, and the audience are all situated’ (Amkpa, 1999, p. 6). Finally, I argue that these situated performances revealed new insights about what it means to be a Tibetan living in exile in India in contemporary times.

Conclusion

In this article, I discussed the methodological process and the tools used to devise participatory research in the form of a theater play titled “Amma la” performed by young Tibetans of refugee backgrounds living in India in 2019. I situated this theater performance in the literature on ethnography and theater and discussed how the play was devised using participatory theater methods. I argued that by enacting and performing embodied experiences about their lives in exile in India in 2019, the Tibetan participants collaboratively co-produced new knowledges about migration, identities, and citizenship in multimodal and visceral ways that invite reflections on the rich potential of participatory research methods in migration research.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Tibetan communities in India who are the true co-authors of this research. Wholeheartedly, I thank the Tibetan organizations in India who enabled and supported the ethnographic research and especially the theater workshops in 2019: Tibet World NGO, Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts, and the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. This research was endorsed by Canterbury Christ Church University, Kent, UK, and Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India, to which the author is extremely grateful. Special thank you to the PhD mentors and academics in the UK who guided this research and offered kind support, mentorship, and inspiration: Dr. Harshad Keval and Dr. Lorena Arocha.

List of supplementary materials

File 1 – “Amma la” Theater playscript

File 2 – Preparatory events

File 3 – Preparatory theater games

Appendix 1 - Table with structure and presentation of ‘Amma la’ data by characters, props, dialogue and languages used

I am thankful to my friend Dr. Nancy Alibhaisi for the brainstorming sessions and her advice on using these methods and thinking together about this methodology as “mixed theater approaches.”