A passion to both identify and work to transform sources of inequity and social harm has long called researchers to utilize participatory and action research methods (Cornwall & Jewkes, 1995; Fals-Borda, 1987; Snyder, 2009). These methods are rooted in collaboration with communities impacted by particular social issues and valuing expertise that comes from the different vantage points community members, researchers, and other relevant social actors provide. Furthermore, these methods embrace a cyclical and iterative process wherein action and reflection, and theory development and deep engagement, are all considered essential aspects of the methodology. Although many have noted the inherent complexity and “messiness” of this approach to research (Cook, 2009; Dancis et al., 2023), insight given into the specific setbacks, pauses, and pivots that can occur within the “mess” often is not sufficiently described in published research. The purpose of this paper is to discuss a community-centered iterative methodological process that responds to existing and emerging understandings of justice issues that can impact research and action.

The process described in this paper centers a methodology learned through a three-year (and counting) community-based participatory research (CBPR) collaboration focused on enhancing the mental health of Bhutanese youth in Cincinnati, Ohio. The initial development of this project grew out of a multi-year relationship with members of the local Bhutanese community and the partner organization, Cincinnati Compass. Members of the Bhutanese community turned to Cincinnati Compass for support related to mental health challenges among their youth. Together as a team that also included two university researchers, we began developing initial plans for a participatory research and action process aimed towards identifying and addressing mental health challenges that prioritized the cultural values and wisdom of both youth and elders in the Bhutanese community.

In 2020, we gained funding support from the Robert Wood Johnson Interdisciplinary Research Leaders (IRL) program to conduct this participatory research. Engaging in this work involved deepening understanding of the injustice Bhutanese families faced during the refugee resettlement process, racist and mental health implications of the pandemic, navigating university policies that were not designed to support community research, and the complexity of existing relationships among community members and organizations. Our iterative approach thus took a community-centered focus as we sought to thoughtfully respond to the different societal and local factors that impact the research and action process. We will share the different cycles of our project, with attention given to how we incorporated a justice-oriented ecological consciousness and how that influenced our collective decisions and actions.

Positionality Statement

Examining how different ecological factors impact our phases of research and action begins with reflection upon how our own identities and past experiences impact our relationships and capacity to comprehend the issues we sought to address (Muhammad et al., 2015). None of the authors (two university professors and the director of the partner organization) are members of the Bhutanese community. Thus, central to our initial work together was a thoughtful effort to gain an understanding of the historical and contemporary experiences of the Bhutanese community, both in learning from community members themselves and external resources. Although each of the authors hold both privileged and marginalized identities, we did not hold any expectations that we understood the experiences of the Bhutanese community, including what it was like to move to the U.S. as refugees and subsequently navigate life in the Midwestern United States. Identifying similar, as well as divergent, experiences that result from holding marginalized identities at times became a source of connection among the authors and the community members. Moreover, it was a shared passion to seek greater equity in our city, dismantle racist barriers, and use research to promote youth mental health in a culturally appropriate and just manner that foregrounded our collective work.

Sharing Our Process

The messiness, and its value, in community research was evident from the start of our process. We (the three authors, who will be referred to as the IRL team throughout the paper) hit submit on our grant proposal for this project on a rainy night, right around the time school closures, restricted travel, and social distancing associated with the COVID-19 pandemic were just beginning to emerge in consciousness and policy. Embracing uncertainty is encouraged in CBPR (Rubinstein-Ávila, 2013; Walton et al., 2015). We were entering a widespread era of uncertainty about what our society, local community, and personal lives would look like, which unknowingly became an asset to our consciousness as we began this research. In this section, we discuss ways our consciousness of uncertainty at various ecological levels and at several moments shaped our collective decision-making and related pauses and pivots.

Power sharing is the cornerstone of CBPR (Dutt et al., 2022; Wallerstein et al., 2019). The IRL team members were keenly aware of our outsider status and the need to center the desires, knowledge, and values of members of the Bhutanese community in all project phases. An advisory team, made up of members of the Bhutanese community, was created to advise on every aspect of the project from research design, community engagement, budget development, and dissemination of findings. As a team — IRL and Advisory — we looked at the full budget to make determinations about stipends for participation, types of activities/events, kinds of training, food and refreshments, and more. It was our team’s desire to truly collaborate on this project to ensure we were intentional about allowing the Bhutanese community to steer this project.

To kick off the project, a series of listening sessions with youth, adults, and elders were held to gain an understanding of the landscape of being a refugee, migrating to the Midwest, establishing community, and navigating new societal norms/expectations. During this time, the IRL team members gained insight into the process of resettlement and contemporary challenges refugees faced, with an emphasis on the meaning they attached to the experiences. Our team always had the desire to be culturally responsive and collaborative with the Bhutanese community and it was through these listening sessions that modifications were made to the original research design to prioritize issues and processes important to the community. Language was altered to reflect preferences of the community. For example, we initially planned to host focus groups with youth across the intersections of age and gender. However, our Advisory Team recommended the idea of “conversation circles” to make the engagement feel less formal and more accessible to young people.

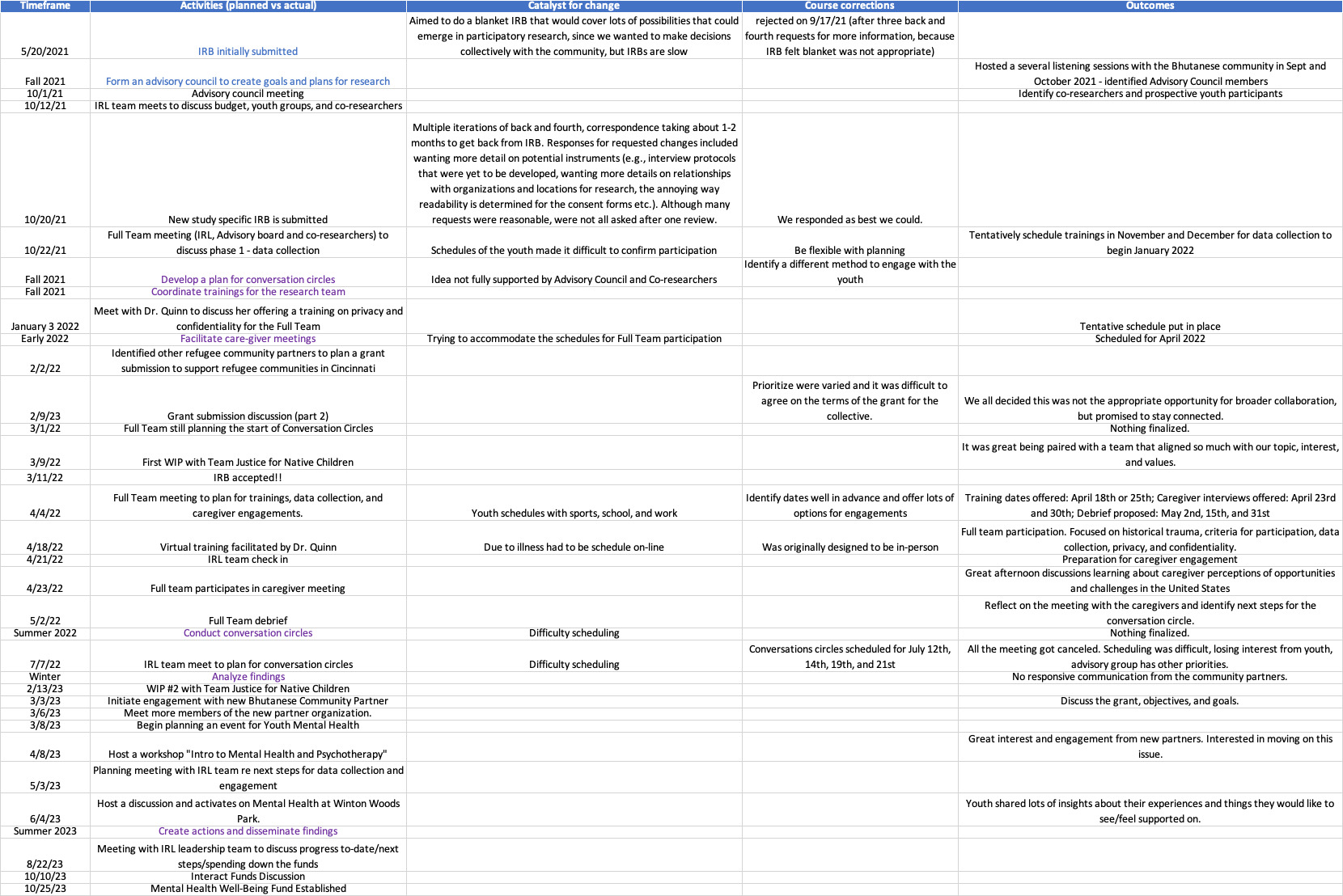

Starting in fall 2021, planning meetings were consistent and productive for the first three months. See Table 1 for a detailed timeline of team activities. As we moved into periods of transition (e.g., end-of-year customs/traditions/holidays) with respect to school, work, and sports, the ability to capture the attention of youth waned greatly, making scheduling activities difficult. Our interactions with youth advisory team members revealed the multiple responsibilities they were juggling, which impacted their ability to fully participate in the project. Bhutanese youth were not only going to school full time, but were also serving as a liaison for their parents and elders, including as translators for parents and elders who did not speak English. When parents and elders had difficulty navigating institutions (e.g., school, employment, social services), youth were there to serve as intermediaries navigating two cultures to help get their family members the support they needed. Youth were working jobs to contribute to their respective households, but also trying to find time to be a “regular” teenager. As a result, young people prioritized sports and time with friends.

These are all issues that would make navigating any project challenging, but COVID-19 complicated life for members of the Bhutanese community in significant ways. Initial activities were planned to accommodate social distancing, which required more meetings with smaller groups of youth. Transportation was an issue and needed to be coordinated across the different types of engagement. However, as meeting dates approached, numerous scheduling conflicts arose. While the core advisory team still met (albeit less frequently) there was consistent communication about next steps and strategies to re-energize the team. By fall 2022, every scheduled “conversation circle” was canceled. Our community partners were indifferent, and our project was in jeopardy of not getting to completion due to the messiness of schedules, life, and the ongoing repercussions of the pandemic.

Reflection among IRL team members revealed that the delayed payments to advisory team members could have played a role in halting the momentum of the project. Our team decided to manage and administer the IRL grant through Cincinnati Compass in an attempt to mitigate university bureaucracy. As with all new programs, the learning curve to get advisory team members paid was longer than initially anticipated. However, as the project proceeded, we were able to take care of payments in a timely manner. By spring 2023, another faction of the Bhutanese community expressed interest in collaborating to address youth mental health. The enthusiasm was welcomed. Plans were immediately scheduled for an “Introduction to Mental Health and Psychotherapy,” community workshop as well as events for data collection. Within a matter of weeks, several activities were scheduled and plans for future engagement were solidified. Collaboration with this new group reignited excitement in the project.

With the end of the IRL Program — and its funding — fast approaching, we needed to find a way to continue the collaboration. We reached out to a local philanthropic organization that focuses its funding and programming at the intersections of health and racial equity. The IRL team proposed the creation of a fund that supported refugee-led approaches to mental health and well-being. The purpose of the fund is to support refugee-led organizations working to address youth mental health and well-being through community-led programming. This funding is intended to support refugee community generated ideas that amplify community power and enhance a sense of connection and belonging. The learnings from our processes and pivots during the RWJ IRL program informed the structure of this fund that would be coupled with community-based organization support. As a result, flexibility is built into project funding to allow unexpected events; funded teams will be part of a learning cohort designed to share best practices with each other; technical support from the IRL team is ongoing through the life of the project and beyond; and funded teams are well positioned to use the outcomes of this project to seed funding opportunities elsewhere. Our proposition was accepted, and we are currently entering into a partnership to support community-centered approaches to address mental health.

Conclusion

By using CBPR, the IRL team was able to deeply engage with the Bhutanese community to identify culturally responsive ways to work towards addressing youth mental health. Our iterative process encouraged us to examine how factors at each ecological level impacted everyone involved and allowed us to refine the project in response. As the clock ran out on the project funding, we sought a next step that would enable us to continue our commitment to the community and utilize the lessons we learned thus far. By transferring funds to a local philanthropic organization that initiated a restricted fund for refugee-led projects, we can further prioritize the goals and desires of refugee communities in uniting research and action for mental health. The organizations we partner with are able to implement a variety of programming and efforts will be supported with data collection and analysis. The goal is for these projects to seed other funding opportunities, as well as shed light on the necessity of funders to provide resources to organizations led by people closest to the problem.

We encourage future researchers to explore methodologies and collaborations that similarly respond to emerging challenges and allow for creative solutions that prioritize community needs and desires. Learning from our experience, we specifically suggest the following:

-

Utilize an ecological framework when assessing the potential challenges that impact CBPR, or when encountering a setback in community partnered research. Don’t assume that one level of analysis can explain why challenges exist and/or can lead to productive solutions.

-

Reach out to funders about transforming projects, even in radical ways, to move your project in a direction that best supports the community, rather than prioritizing traditional expectations of funded academic research.

-

Be open and transparent about the difficulties you experience in collaborative research and how you attempt to address them, whether successful or not.

-

Externalities will always complicate the research process, especially when you are collaborating with diverse stakeholders. Settle into the reality that flexibility is critical to CBPR.

-

Be authentic and mindful in the ways you engage with the community to ensure that the research process is not extractive and reproduces harm.

We believe that utilization of these suggestions can enhance the ability of research to support social justice aims.

Author Note

This research was funded through a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Interdisciplinary Research Leaders Fellowship to the three authors. We would like to thank our community partners for their countless contributions to this work.