Community Engagement and Health Equity

Community engagement (CE) is “the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1997, p. 9). Participatory approaches and community-driven solutions like CE are noted as powerful strategies that can help facilitate health equity (Ortiz et al., 2020). CE promotes health equity by facilitating 1) bidirectional trust and mutual respect and 2) honoring and integrating the dynamic perspectives, values, and lived experiences of the individuals impacted by structural discrimination and oppression (Everette et al., 2023). Without intentionally and meaningfully engaging impacted communities and leveraging their insights to directly alter programs, practices, and policy, current inequities will likely be exacerbated or preserved (Everette et al., 2023).

Significance of Engagement Strategies in Community and Academic Partnerships

It is imperative to have appropriate and systematic methods for engagement because partnership engagement in research might be unorganized, complicated, ineffective, and leave community stakeholders feeling subjugated (Staley, 2009; Young et al., 2021). As a result, the research and its intended impact may not be actualized, and researchers may jeopardize the community-academic partnership. Many current engagement tools focus on enhancing partnership engagement, often concentrating on partnership governance (Greenhalgh et al., 2019) and preparing researchers and communities for engaging with one another (Ahmed & Palermo, 2010; Joosten et al., 2015).

The literature needs more systematic and time-efficient tools to guide decision-making in community-academic partnerships. One tool, the Action Learning Series, used action learning and system thinking strategies to guide stakeholders’ development and dissemination of a resource focused on enhancing patient-provider relationships to address hypertension (Young et al., 2021). The Action Learning Series consists of four three-hour working sessions, 30-minute follow-up meetings, and “homework” assignments. Community partners may be unable to invest significant time in decision-making processes like the ALC because their time is devoted to low-resourced communities serving vulnerable populations. Thus, they often require efficient and clear strategies to guide collective decision-making with their research partners.

In this brief, we will use an example of developing data collection protocols, and surveys focused on understanding community benefits agreements (CBAs) as a strategy for addressing structural racism to illustrate the use of an efficient and clear decision-making engagement strategy to garner critical feedback from community partners.

CARES: A Community and Academic Engaged Partnership

Community Agreements: Repairing Economic Segregation (CARES) is an economic justice community-academic project based in St. Louis, MO, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Interdisciplinary Research Leaders Program. The project aims to understand the extent to which CBAs disrupt the pathways from residential segregation to area-level disadvantage for historically oppressed communities. We focus on CBAs, which are legally enforceable contracts implemented in segregated, historically oppressed neighborhoods negotiated between property developers and organizations representing the interests of the community where the development occurs. These contracts promise a range of benefits to the neighborhood, such as affordable housing, the addition of green space, local hiring programs, and neighborhood spaces in exchange for community support and sometimes expedited approval processes.

However, little research has examined how CBAs have delivered on promises to the community and disrupted the pathways that lead from residential segregation to poor health. Broadly, our project explores the process of developing a CBA and the impacts of previously implemented CBAs. We have situated CE as the foundation of our project. In describing our application of a community-engaged, decision-making framework, we will focus on the development of the deep canvassing data collection protocol we used to knock on the doors of community members’ homes and engage in short conversations to understand the health and economic-related aspirations of a community developing a CBA.

The RAPID® Framework: A Strategy for Community Engagement

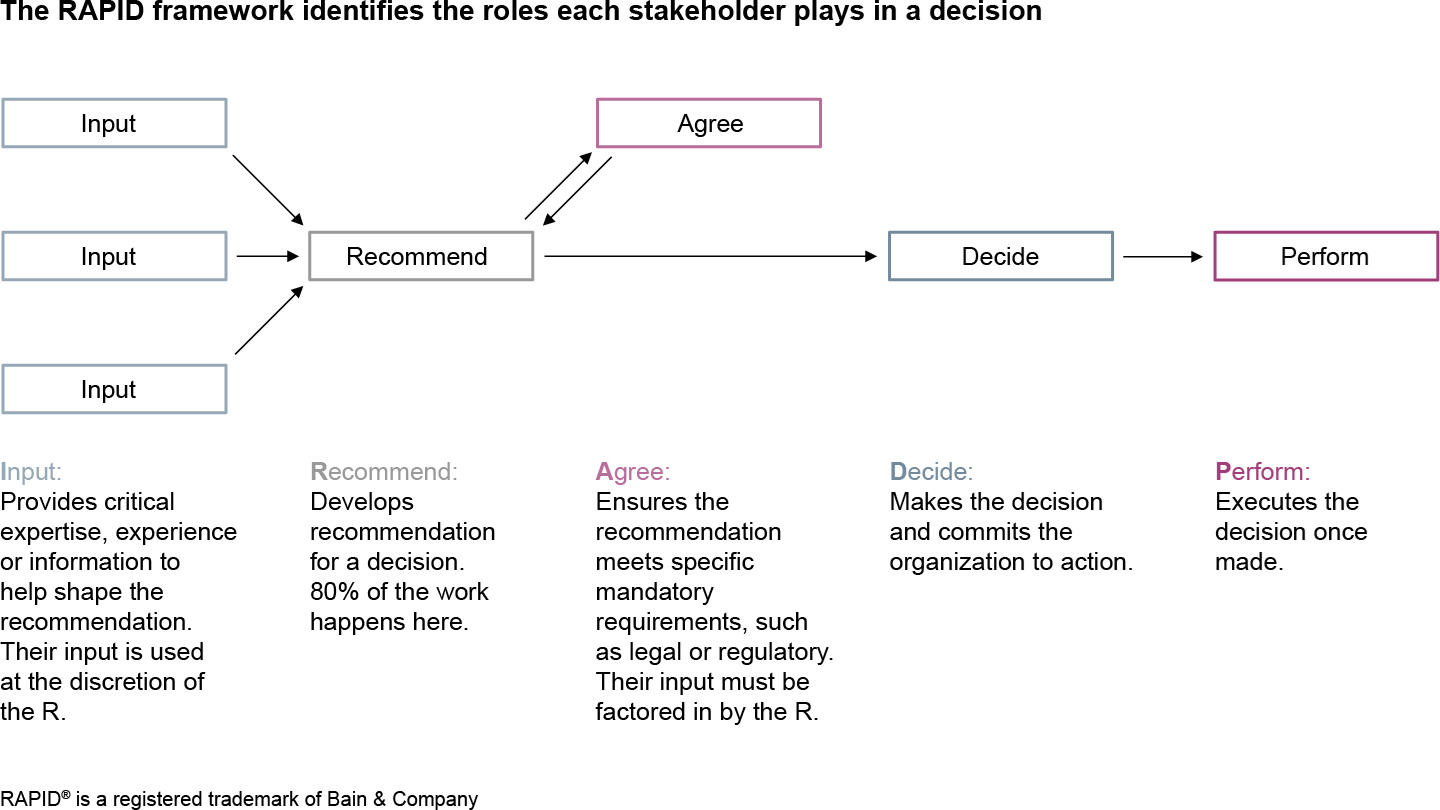

In the CARES project, we intentionally integrated methods and tools that guaranteed efficient, collaborative, and transparent decision-making among community and research partners. One of these tools is the RAPID® decision-making framework. RAPID® is an acronym that describes decision-making roles: Recommend, Agree, Perform, Input, and Decide. RAPID® assigns roles in a stepwise decision-making process to clarify who provides input or feedback on a decision, who decides, and who implements the decision. The RAPID® allows for accountability in the decision-making process and diverse, vital partners to share their expertise and provide direction during critical moments in the decision-making process (Bain & Company, 2023).

This framework was developed by Bain & Company and is often used in the management consulting field. The RAPID® allows for power sharing amongst people and groups that may typically revert to traditional power dynamics and creates a more equitable foundation for sharing power in a decision by assigning roles and imposing transparency (Ciccarone et al., 2022). We applied this framework in a community-academic partnership to generate meaningful data collection protocols and measures for our project. The framework consists of five components, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Although the framework is presented as RAPID, often, as indicated by Figure 1, the order of the RAPID® components that is logical in practice is Input, Recommend, Agree, Decision, and Perform.

We chose to implement the RAPID® framework because it provided the opportunity for our community coalition partners to share their expertise and provide direction at critical moments during the CARES research project. Specifically, it provided a systematic and collaborative process that activated community power in co-creating deep canvassing data collection protocols and measures that would ultimately benefit communities that seek to understand community needs and use CBAs to address socioeconomic and health inequities in disinvested communities.

CARES Implementation of the RAPID® Framework

We used the RAPID® framework to co-create CARES’s deep canvassing protocols and data collection instruments with community partners. The CARES team scheduled two 90-minute meetings with two partnering non-profit community organizations comprised of leaders and residents who had expert knowledge of CBAs, reflected gender and racial diversity, and resided in St. Louis communities with similar disenfranchisement as our designated deep canvassing community. The organizations served as thought partners in our deep canvassing efforts. The organizations received a monetary honorarium for the groups’ time and expertise. Community Partner A was a new organization that aimed to be a developer as they sought to purchase property and enter into a CBA with a local community. Community Partner B was an established advocacy organization comprised of local community leaders who negotiated and enforced CBAs with financial institutions. Both meetings included a presentation and agenda, relationship-building activities, a review of the project and specific deep canvassing aims, and a five-minute break. While the partners represented their respective organizations, they participated as individuals in the RAPID® process.

In the first meeting, CARES met with each partner separately. We informed the partners that we would use the RAPID® process to guide our choices regarding the deep canvassing protocols and data collection instruments. Using Figure 1, we provided a detailed explanation of the framework’s roles and how the roles related to giving feedback about deep canvassing processes and questions. It is essential to highlight that the community partners were in the Agree role, meaning if they did not agree with the canvassing protocols and measures recommended, the Recommend party had to return to Input and reevaluate and propose a new course of action (see Table 2 for role assignments).

Once the partners’ roles were explained, we presented our deep canvassing launch plans and data collection scripts for communicating with the residents. The partners reviewed the materials, and we talked about what changes needed to be made. Next, the partners were presented with a matrix that included 17 data collection instrument questions. The instrument questions were located in the foremost left column. The top row of the matrix included a set of criteria (see Table 1) that the partners were to consider as they evaluated each question. Each question had space for the partner to include their comments. The last column in the matrix was where the partners included their first and last initials to indicate their vote for that particular question. The CARES team and community partners were given 15 minutes to review the matrix, write comments about the questions, and vote for the five questions they believed best fit the criteria. Next, we discussed the comments and chosen questions with the partners. After the discussion, we summarized the meeting and informed them of the steps to edit the protocol and measures, which we would share during the next meeting.

After the first meeting, the CARES community partner co-led in her Recommend role, revised and consolidated the suggestions and voting options. Both community partners were present in the second meeting, and the CARES team revealed the recommended processes, script, and questions. In their Agree role, the partners reviewed the revised materials and approved them for the next phase of the RAPID® process. The CARES team owned the Decide and Perform roles. We ensured the deep canvassing materials aligned with the research goals and implemented the deep canvassing data collection effort once all the materials were finalized.

RAPID® Framework Lessons Learned and Future Directions

The RAPID® proved to be a systematic, efficient, and transparent process. The CARES team and the community partners were clear on their roles and, therefore, could execute them to the highest standard, which included providing nuanced feedback about the deep canvassing data collection process and questions in a relatively short period. The RAPID® helped us streamline the number of data collection questions we asked (from 17 to 9) and restructure the questions for clarity and alignment with the deep canvassing goal.

With the aid of the RAPID®, we learned from the community partners to:

-

Make the purpose of the overall research project clear.

-

Reflect on CARES’s relationship to the community we are canvassing and consider developing a deeper relationship with the residents.

-

Be clear about how the research will help the community.

-

Consider working hand in hand with a credible organization already engaging in CBA work.

-

Understand that more than relationships with elected officials and neighborhood associations are needed to build trust/relationships with community residents.

In our experience of implementing RAPID®, we acknowledge a deep understanding of the RAPID® components is essential for participants because if not, roles and responsibilities can be unclear and hamper effective decision-making. While implementing the RAPID®, intentional communication is imperative. The individual assigned to the Input role must document and share information with partners to ensure they stay informed throughout the process. This includes partners being promptly informed of what and why decisions were made to guarantee everyone is reading from the “same page” and can bask in the power of a shared vocabulary. Due to our experience, we agree with Ciccarone (2022) that it is important to differentiate between moments of seeking partners’ feedback for decision-making and informing them about decisions already made to reduce confusion and ensure appropriate feedback is obtained. Teams using the RAPID® framework should evaluate partnership engagement and satisfaction by adapting assessments like the Research Engagement Survey Tool (Goodman et al., 2022) or developing satisfaction surveys, observational tools, or interview guides that can provide insights on improving future implementation.

The transformative decisions and knowledge garnered from the RAPID® process resulted from our community partners tapping into their community power and resilience assets. Our community partners exercised their power by collectively voicing their community’s culture and expectations. Through their resiliency from prior discriminatory and oppressive experiences, they had a clear vision for CE and investment and, therefore, could firmly exert their power when collaborating with us to protect the community from experiencing additional inequities. Thus, researchers must be exceptionally deliberate about CE and employ efficient and structured methods such as the RAPID® to effectively leverage community partners’ power and resilience in decision-making processes that enhance research to address current and historical inequities (Everette et al., 2023).