Background

In the United States, 2020 is described as the year of racial reckoning. Video footage of the brutal and racially-motivated deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd — rallying cries of the Black Lives Matter movement — coupled with the rampant spread and excess COVID-19 deaths experienced among communities of color (Polyakova et al., 2021), created the conditions with which our nation was compelled to acknowledge our racism and its devastating impact on communities of color (Kares & Broussard, 2023).

The racial reckoning of 2020 propelled well-established public health efforts to acknowledge and eliminate racial/ethnic inequities in health into the limelight (Davis, 2000). At this time, a national movement of state, county, city, and school district-level municipalities began declaring racism as a public health crisis. According to the American Public Health Association (APHA), to date, there have been at least 265 entities that have declared racism a public health crisis or emergency. While APHA (n.d.) acknowledges that “resolutions and formal declarations are not necessarily legally enforceable,” they are a catalyst for meaningful change. Indeed, as authors Méndez et al. (2021) write, “recognizing and naming racism as a public health crisis is a critical first step in dismantling structures and systems of oppressions that not only impede health and well-being but contribute to racial inequities in health” (p. 1). As these declarations focus on structures and systems, they move us closer to understanding and dismantling the root cause of health inequities, the systemic racism embedded within our policies and practices regarding education, food, housing, employment, healthcare, and more (Bailey et al., 2021; K. D. Key et al., 2023; Williams et al., 2019).

Systemic Racism and Health

For the past four decades, a vast and extensive body of research has documented the relationship between racism and poor physical and mental health outcomes (Bailey et al., 2017; Massey et al., 2021; Misra et al., 2021). Racism, racial discrimination, and their resulting trauma are not only found to damage health over the lifespan but can also cause transgenerational harm. Systemic racism presents itself as a host of chronic stressors to which people of color are exposed (Assari et al., 2018). Prolonged, chronic stress and race-based chronic stress have been associated with significant wear and tear on the body (Chae et al., 2014; Drury et al., 2015; Geronimus et al., 2006; Oliveira et al., 2016; Zahran et al., 2015). This physiologic damage is shown to impact not only individuals but also have transgenerational consequences. For example, race-based chronic stress, coupled with structural barriers to accessing healthcare, not only impacts pregnant women of color but also impacts fetal development and birth outcomes (Goosby & Heidbrink, 2013; Kuzawa & Sweet, 2009)

Chronic and prolonged exposure to systemic racism poses a significant and persistent threat to the immediate and long-term health of people of color. While public health professionals have long recognized and worked to call attention to the deleterious effects of racism on health, the racial reckoning of 2020 provided ripe conditions for advancing this work. At this time, a growing number of state and county leaders, including Genesee County, Michigan, declared racism a public health issue (APHA, n.d.).

Declaring Racism a Public Health Crisis in Genesee County, Michigan

In June 2020, Dr. Kent Key (a local public health scientist) and Nayyirah Shariff (a local activist and community organizer) co-authored a resolution declaring racism a public health crisis. This resolution was presented and passed by the Genesee County Board of Health and, weeks later, by the Genesee County Board of Commissioners (Diaz, 2020). Broad community support in the form of public comment for the resolution was provided by members of the Greater Flint Taskforce on COVID-19 and Racial Inequities, an interdisciplinary team of community organizers, philanthropic leaders, academicians, and local government leaders, henceforth referred to as the “Taskforce,” representatives of community-based organizational partners (CBOP) — an umbrella organization of more than 30 community-based organizations, and faith-based leaders of the Greater Flint Taskforce on COVID-19 and Racial Inequities, Faith-based Subcommittee, henceforth referred to as the “Faith-based Subcommittee.”

The passage of the resolution represented a small victory. The declaration helped to increase awareness about the relationship between racism and poor health but did little to produce tangible change within Genesee County. Indeed, members from CBOP pressed for more to be done by directly asking the academic author of the resolution, “So, what? What’s next?” The challenge to operationalize racism as a public health crisis was waged, raising important questions for Dr. Key and those involved in supporting the resolution’s passage, such as, “How do we, academic and community partners, operationalize this resolution to bring about tangible, meaningful, and sustainable change? How do we propose to end systemic racism? Where do we begin? What problems or issues should be prioritized?”

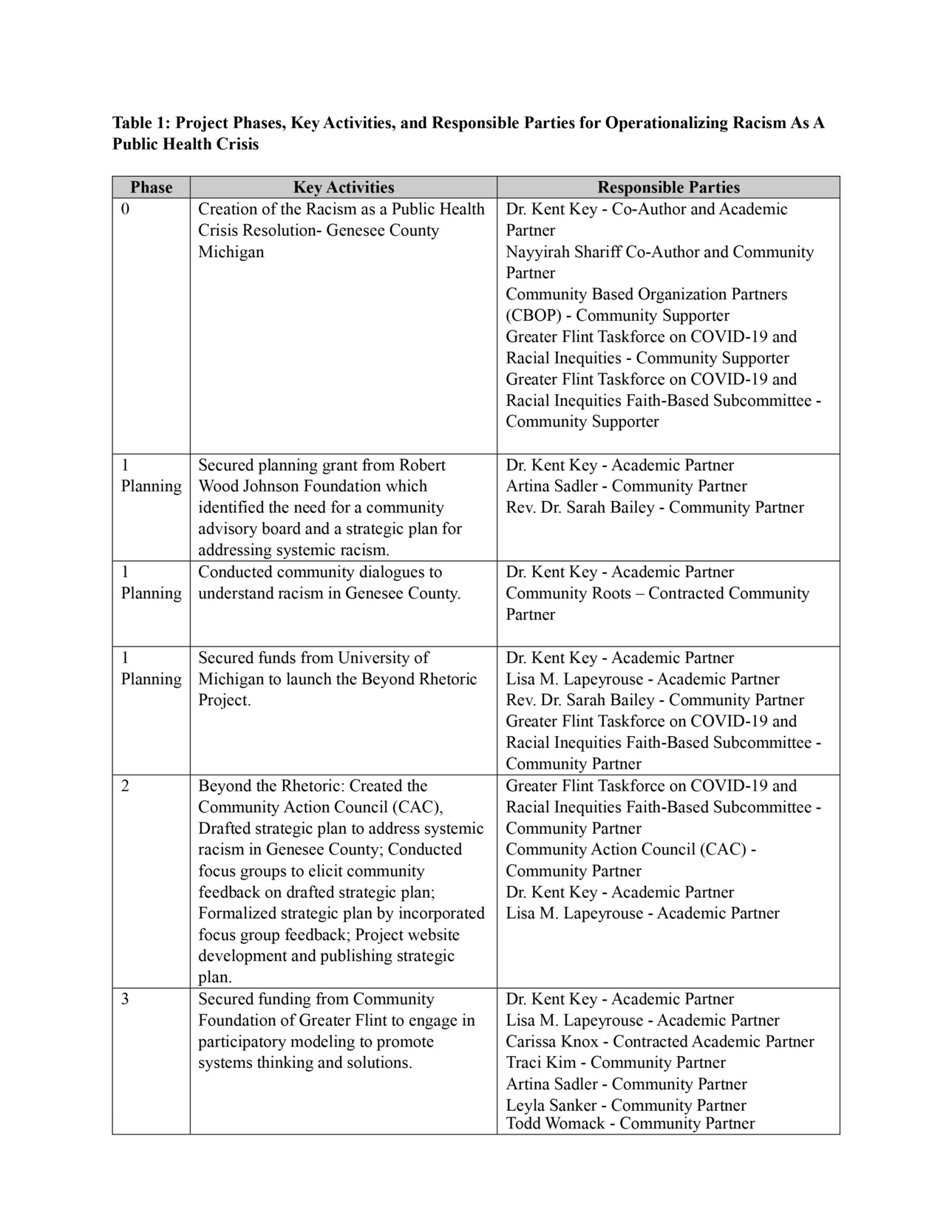

The first phase of operationalizing racism as a public health crisis involved community (Artina Sadler and Rev. Dr. Sarah Bailey) and academic (Dr. Kent Key) partners securing a planning grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). In partnership with the Faith-based Subcommittee, Dr. Key utilized the RWJF grant to identify and prioritize steps to operationalize racism as a public health crisis, which included: 1) Forming a community advisory board; 2) Engaging community members in discussions about racism in Genesee County; and 3) Developing a strategic plan to identify and address systemic racism in Genesee County. As depicted in Table 1: Project Phases, Key Activities, and Responsible Parties for Operationalizing Racism as a Public Health Crisis, Phase 1 activities included: 1) Undertaking efforts to form a community advisory board; and 2) Hiring Community Roots, a Flint-based community think-tank aimed at envisioning healthy, inclusive, and thriving communities (North Flint Neighborhood Action Council, n.d.), to facilitate a series of community dialogues to explore attitudes and beliefs about the origins of racism, racism within Genesee County, and steps necessary to reduce racism.

As part of identifying potential community advisory board members, members of the Faith-based Subcommittee put forth Dr. Lisa M. Lapeyrouse’s name as a possible academic collaborator. Prompted by this suggestion, Dr. Key invited Dr. Lisa M. Lapeyrouse (associate professor in the Department of Public Health and Health Sciences) at the University of Michigan-Flint to partner on a research grant specifically aimed at developing a strategic plan to address systemic racism in Genesee County, Michigan. The project “Beyond Rhetoric” was developed by Drs. Key and Lapeyrouse, in collaboration with Rev. Dr. Sarah Bailey of CBOP, and funded by the Center for Poverty Solutions at the University of Michigan.

With the newly secured grant, Phase 2 of operationalizing racism as a public health crisis began. Defining activities of Phase 2 included: 1) Creating a community advisory board; 2) Engaging the advisory board in a strategic planning process to draft a strategic plan to identify and address systemic racism in Genesee County; 3) Conducting focus groups to solicit feedback on the drafted strategic plan; 4) Incorporating feedback into the drafted plan; and 5) Creating the Beyond Rhetoric website to share the community-identified priority areas for addressing systemic racism within Genesee County.

At present, we are in Phase 3 of operationalizing racism as a public health crisis. This phase focuses on determining points of intervention to address strategic plan priority areas identified in Phase 2. With funding from the Community Foundation of Greater Flint, our team of academic researchers (Drs. Key and Lapeyrouse and Carissa Knox, a doctoral candidate in Resource Policy and Behavior), community partners (Traci Kim, Artina Sadler, Leyla Sanker, Todd Womack, and Taskforce members), and Genesee County residents are utilizing a participatory modeling approach to promote complex systems thinking to illuminate root causes of systemic racism and potential levers of change (Voinov et al., 2018).

This manuscript shares the community engagement and participatory processes, models, and tools used to operationalize (systemic) racism as a public health crisis in Genesee County, Michigan. We focus on the various processes employed and share our best practices for working with community partners to advance efforts to dismantle and eliminate systemic racism.

Research Design and Methods

As stated by Dr. Lafronza (2020), President and CEO of the National Network of Public Health Institutes, “The harmful health effects of racism cannot and must not be ignored or denied. While no one has the power to change the past, every living individual has the power to change the future” (Lafronza, 2020). Because of the detrimental effects of racism on the health of populations of color (Geronimus et al., 2006; Paradies, 2006), it is imperative that systemic racism be ended. This work, however, will require that public health professionals collaborate with those most affected by systemic racism, as they possess crucial knowledge about effective strategies to reduce and end it (Galarneau, 2020). Specifically, community residents and stakeholders must be present at decision-making tables, be fairly compensated for their contributions, and be given appropriate decision-making power to have an impact (Galarneau, 2020). Consistent with this, as public health researchers, we ground our work in community engagement strategies, where deliberate action is taken to honor local knowledge and leadership by having community members take the lead in determining problems, priorities, and solutions. Our research work also employs public health frameworks such as the social determinants of health and the socio-ecological model to facilitate an understanding of how systemic racism impacts health, as well as the need for multiple-level approaches to dismantle it.

Community-Engaged Research

The current research employs community-based participatory research (CBPR) practices and other forms of community-engaged research. CBPR is considered a form of action research that historically has been employed to address social problems (Holkup et al., 2004). Action research is a distinct type of research that aims to simultaneously understand and solve social problems through a participative process (Casey et al., 2021). CBPR requires active community participation at every stage of the research process (Holkup et al., 2004). CBPR aims to facilitate mutual learning and co-creation between community and research partners through sharing knowledge and expertise (Israel et al., 2001). The formation of equitable partnerships is another foundational component of CBPR. To do this, CBPR stresses that researchers must address equity factors (i.e., power, transparency, ownership, and decision-making) when forming community partnerships. Finally, community-engaged research practices aim to ensure that community problems and their solutions are both community-defined and determined. In this way, community-engaged research facilitates sustainability through community ownership.

Social Determinants of Health (SDoH)

Declaring racism as a public health crisis/emergency provides the opportunity to view racism through the various systems that impact the lives of people of color. While most people are socialized to view racism as interpersonal, public health models and theories challenge us to shift our view to a systems perspective. In particular, a focus on the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) — defined as the conditions in which we are born, live, work, and play — requires that we consider how our social systems and structures not only disproportionately expose people of color to health threats, but impose and reinforce barriers to care as well as other opportunities that promote good health (Braveman et al., 2022).

Social factors, such as income, are significant predictors of racial/ethnic health inequities. For example, poverty reduces access to resources (i.e., safe neighborhoods, stable housing, and affordable healthy foods) critical to a healthy life. Further, poor communities are exposed to water and air pollutants at significantly greater levels than affluent ones. Poor individuals and communities also face greater barriers to accessing and paying for healthcare. Collectively, this constellation of health threats results in increased risk for communicable (i.e., HIV, COVID-19, etc.) and noncommunicable (i.e., diabetes, hypertension, cancer, etc.) diseases, disability, and premature death. Health inequities experienced by poor individuals and communities, especially poor communities of color, are largely linked to social factors and not individual health behavior. As Braveman and colleagues (2022) suggest, systems, policies, and practices rooted in white supremacy systemically and pervasively disadvantage people of color. Developing a strong understanding of the SDoH and its relationship to racial/ethnic health inequities is an important method for helping community residents, stakeholders, and systems leaders view racism as a systemic (vs. interpersonal) issue.

Socio-Ecological Model

The Socio-Ecological Model (SEM), developed by Urie Bronfenbrenner (1979), is a systems approach for planning health interventions. Notably, this model argues that human behavior is shaped by multiple levels of influence (i.e., individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy). As such, this model breaks away from simplistic understandings of health and health behavior that often “victim blame” individuals for their poor health. Rather, SEM helps explain how health and health behaviors may be helped or hampered by the environments in which people live and work.

The SEM has been used to address a wide range of health issues, including racial/ethnic health inequities (Reifsnider et al., 2005). SEM posits that multi-level interventions are essential to ensuring maximum impact for a given health issue, problem, or barrier. We employed SEM to contextualize racism as a systemic issue. This model will also ensure any intervention efforts or proposed solutions target multiple levels of influence. To eliminate systemic racism, we must move beyond our traditional focus on individual and organizational-level interventions to include policy-level solutions. Indeed, a promising and growing body of research shows that policies regarding income, such as increased access to nutrition through Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), are associated with better health outcomes (Adler et al., 2016). Thus, as racism is encountered at every level of a system, we must consider how our intervention efforts will effectively address them.

Committee Composition Matrix

Research concerning systemic racism requires partnering with community members impacted by racist policies and practices. Likewise, CBPR requires that community residents and stakeholders participate in research to develop relevant, culturally and linguistically appropriate programs, services, and solutions. In line with this, Phases 1 and 2 of our research involved the recruitment and creation of a community steering committee, later named by the committee, the Community Action Council (CAC).

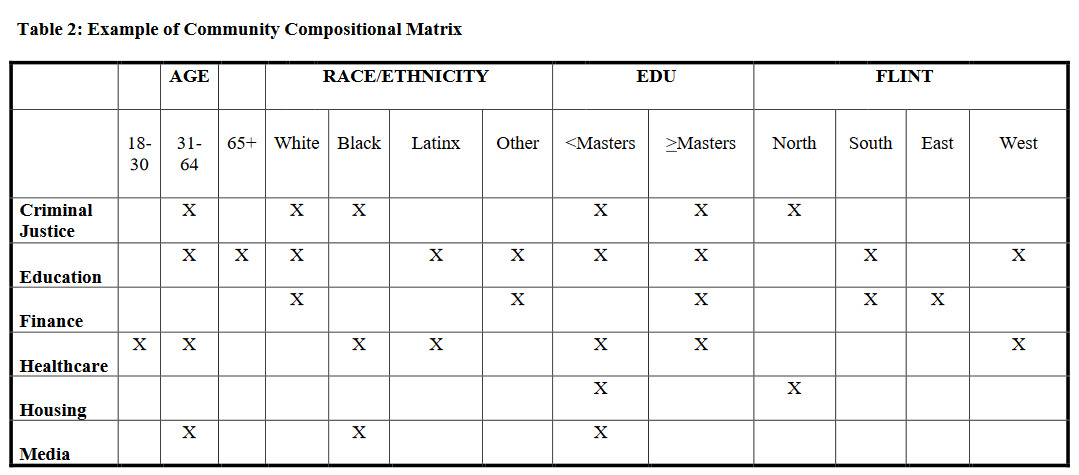

To strategically create a CAC that represents different racial/ethnic groups, professional fields (i.e., finance, education, health), and geographic locations within Genesee County, we solicited candidate names from CBOP, the Taskforce, and the Faith-based subcommittee. As names were put forward, we populated them into a matrix to help identify gaps that were then used to direct additional recruitment efforts. Specifically, we adopted a board/committee compositional process and tool by boardsource.org for nonprofit organizations. The process involved academic (Drs. Key and Lapeyrouse) and community partners (CBOP, the Taskforce, and the Faith-based subcommittee) identifying key characteristics we wanted to be represented on the CAC. Once key characteristics for committee membership were identified, a committee composition matrix was created and used to guide recruitment efforts.

Agreement over key characteristics for CAC membership was easily achieved and straightforward. Demographic characteristics such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, and education level were deemed relevant and adopted. Additionally, a clear and shared understanding among academic and community partners alike was that efforts to address systemic racism would require conversations about the interconnections between different systems. Thus, individuals employed in various occupational sectors were deemed critical to the CAC. Likewise, creating a shared vision for a county-wide strategic plan to address systemic racism within Genesee County required representation from individuals throughout the county. Thus, geographic location was an additional characteristic added to our committee compositional matrix.

In the City of Flint, situated within Genesee County, there are many community activists and champions of health equity issues. Most of us know each other and have worked on several projects together. A concern that the academic partners on this project had is whether repeatedly working with the same community groups and representatives diminishes our ability to learn, think, and develop innovative solutions. Do we think too much alike? Which voices are not represented among these familiar groups? Has our collective memory hampered what we believe is possible because of past experiences?

The development and use of a committee compositional matrix provided an objective method for examining the potential composition of our CAC. Rather than defaulting to working with “the usual suspects,” this tool helped us, the academic partners, stretch to form new partnerships. The composition matrix also helped us, the academic partners establish a CAC with a more equitable representation of Genesee County residents (i.e., Flint and non-Flint residents). Finally, the composition matrix helped to illuminate the lack of youth representation in the CAC, which led to a separate but complementary project examining the attitudes, beliefs, and experiences of youth regarding racism in Genesee County (K. Key, 2021).

Names put forward by our community partners (Taskforce, Faith-based Subcommittee, and CBOP) were contacted via email and informed about the Beyond Rhetoric Project. When possible, nominators of specific individuals were included in recruitment emails in the hopes that a familiar name would elevate one’s consideration of our request to serve on the CAC. Information regarding expectations for participation, such as length of commitment, estimated number of hours per month, and compensation, was included. Specifically, we asked for a six-month commitment, where members would attend approximately one two-hour meeting each month. As part of this six-month commitment, CAC members were expected to draft and finalize a strategic plan to address systemic racism within Genesee County. For this work, CAC members were compensated at a rate of $25 per hour for a total of $50 per meeting. All persons contacted were asked to supply additional names of people they believed would be a good fit for the CAC. Our efforts resulted in an ethnically diverse, 13-member council. Among CAC members, women composed 54%, while men composed the remaining 46%. African Americans composed the largest racial/ethnic group (61%), followed by whites (23%), Arabs/Middle Eastern (8%) and Hispanic/Latinx (8%). The most common occupational fields represented were education (15%), media (15%), health (15%), law enforcement/criminal justice (15%), and general community organizer (15%), followed by finance (8%) social work (8%), and ministry (8%).

CAC Partners

Members of our CAC (listed in alphabetical order) included: 1) Devin Bathish of the Arab American Heritage Council; 2) Canisha Bell of Black Girls Do Yoga, a Mindfulness Initiative of the Crim Fitness Foundation; 3) Artina Carter, Chief of Diversity, Huron-Clinton Metroparks; 4) Karen Church, President ELGA Credit Union; 5) Percy Glover, Executive Director of Community Engagement at the Genesee County Sheriff’s office; 6) Tricia Hill, Deputy Superintendent of Genesee Intermediate School District (GISD); 7) Jiquanda Johnson, journalist and founder of Brown Impact Media; 8) Rev. Dr. Daniel E. Moore, SR., DMin., co-chair of the Greater Flint Taskforce on COVID-19 and Racial Inequities, Faith-based Subcommittee, and Senior Pastor at Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church; 9) Mark Nichols, freelance content creator and Digital Media Coordinator for Flint Institute of Arts (FIA); 10) Aurora Sauceda Coordinator for Michigan United’s Public Health Navigator Program and foundering member and coordinator for Latinos United for Flint — a coalition of local Latino organizations and concerned citizens working to enhance the lives of the Hispanic/Latino community during and after the Flint Water Crisis; 11) Lieutenant Leon Skinner of the Office of Genesee County Sheriff; 12) Erica Thrash-Sall, Executive Director, McFarlan Charitable Corporation; and 13) Todd Womack, MSW, Program Manager and lecturer in Social work at the University of Michigan Flint, Pastor of Central Church of the Nazarene, and founding member of Community Roots.

Community Dialogues

Between January and February 2021, Dr. Key, in partnership with Community Roots, organized four virtual community dialogues to explore attitudes and beliefs about the origins of racism, racism within Genesee County, and steps necessary to reduce racism within Genesee County. Community Roots, founded and directed by three Flint natives — Sylvester Jones, Patrick McNeal, and Todd Womack — was contracted to facilitate these community conversations. Principles of the World Café model, which center on developing a common vision and collaborative dialogue to tackle social issues faced by a local community (Brown & Isaacs, 2005), were adopted to guide these conversations. Participants were recruited using a variety of methods, including, but not limited to, printed flyers, email, and word of mouth. In total, there were 165 participants. Data was gathered using Jamboard and a 12-item demographic survey. Jamboard is a tool used for synchronous, online collaboration and users can create individual “sticky notes” in response to prompts, which can be collectively organized by theme. Jamboard is often employed in educational settings to help students demonstrate their understanding of a story, process, or concept (Clark, 2020). For our use, participants were asked to create notes in response to the following questions:

-

When you are fast asleep, a miracle happens, and racism is eliminated. But since the miracle happened overnight, nobody tells you that the miracle happened. When you wake up the next morning, what will you notice?

-

From your point of view and in your honest opinion, why does racism exist?

-

On a scale from 1 to 10, 10 being perfection and we live in an anti-racist county, where would your group rate Genesee County?

-

From where you and your group rated Genesee County, what would need to happen to move the rating one point higher towards 10?

A total of 776 comments were analyzed across the four community dialogues. The majority of participants were white (48%), followed by Black/African American (41%), and Other (6%). Women (65%) comprised the largest group of participants, followed by men (31%) and non-binary individuals (2%). Finally, the majority of participants were between the ages of 16–30 (43%), followed by 45 and older (36%), and 31–44 (20%). While a detailed account of the findings is outside of the scope of this manuscript, we will highlight the major takeaways.

First, participants’ responses focused on interpersonal understandings of racism, not systemic racism. For example, when asked “If racism was eliminated overnight, what would you first notice?” responses centered on imagined interpersonal encounters such as people showing kindness to one another and smiling at each other. Second, when participants were asked about steps necessary to reduce racism within Genesee County, responses again focused on interpersonal-level solutions such as having conversations and acknowledging that racism exists within our community and the larger society. Indeed, a consistent sentiment expressed was that a change in mindset was needed to eliminate racism. Third, while participants were able to draw connections between systemic racism and local issues such as crime, education, and the justice system, root causes of systemic racism were largely attributed to individuals (i.e., behavior and feelings of superiority) and not specific policies or practices. These findings foreshadow the challenges we continue to encounter in our work to advance efforts to dismantle and eliminate systemic racism.

Strategic Planning

While our community dialogues were underway, we continued recruiting and finalized our CAC. During this time, we also hired Dr. Lynda Jefferies, a senior consultant at the Leadership Group LLC with considerable experience in leading strategic planning and working on issues of racial equity. Dr. Jefferies was contracted to facilitate our strategic planning meetings with the CAC. Between February and April 2021, the CAC met eight times via Zoom to draft a three-year strategic plan to address systemic racism within Genesee County.

To nurture trust among CAC members, “touchstones” from the Taskforce were introduced and adopted. These touchstones provide guidance for engaging in difficult, emotionally charged, collaborative work. Examples of touchstones include: listening intently to what is said while also listening to the feelings beneath the words; suspending judgment and refraining from correcting, debating, or interpreting what someone else has said; speaking one’s truth and trusting that your voice will be heard and your contribution respected; and turning to wonder when things get difficult i.e., “I wonder what my reaction teaches me?” (Community Foundation of Greater Flint, n.d.).

Effective collaboration among community and academic partners requires trust. Establishing such trust requires a long-term and sustained commitment. For the current project, our community and academic partners were uniquely positioned to undertake the ambitious task of developing a strategic plan to address systemic racism within a six-month timeframe. As previously discussed, a strong group of community activists exists within the Flint community. These leaders frequently partner with one another and have partnered with one or both of the academic partners on this project. Thus, while not intentional, most CAC members had a history of working with one another as well as with the academic partners. This history of trust between and among our academic and community partners was instrumental to engaging in timely, equitable, and effective decision-making (i.e., each CAC and academic partner having one vote and compromising to the point in which everyone could “live with the decision”) and centering community voice. Another key factor in operating efficiently was the fact that eleven members (84.6%) missed two or fewer CAC meetings.

The first CAC meeting was used to establish a meeting schedule and work plan that included key dates for project deliverables, such as the completion of the drafted strategic plan. Before the first meeting, CAC members were emailed a copy of Community Roots’ report on the community dialogues conducted (Bassett & Gordillo, 2021). During the first meeting, an overview of the findings from the community dialogues was presented as a springboard for discussing racism in the different social systems represented by the CAC (i.e., law enforcement, education, finance, etc.) and more broadly. In these early discussions, it became abundantly clear that members had different understandings of racism. While all members demonstrated a clear understanding of interpersonal racism, much fewer expressed a clear understanding of how residents of Genesee County encounter and experience institutional racism and systemic racism. Importantly, this lack of understanding was found among both white CAC members and CAC members of color. Additionally, CAC members differed in their ability to acknowledge their own participation in racist systems, structures, policies, and practices. Statements about “treating everyone fairly” and following corporate hiring and promotion practices based on individual merit were expressed. These conversations proved not only difficult but time-consuming as CAC members worked to develop a common understanding of systemic racism. To aid in this process and keep meetings focused on drafting a strategic plan, an online folder was created with various educational resources for CAC members. Resources provided to CAC members included, but were not limited to: the University of Washington’s School of Public Health (2019) Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Glossary of Terms; the College of the Holy Cross (n.d.) How to Write an Anti-Racism Action Plan: A Self-Paced Guidebook; the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (n.d.) Racial Equity Resource Guide; Pérez-Stable and Hooper (2021) Acknowledgement of the Legacy of Racism and Discrimination; Human Impact Partners (2021) How Health Departments Can Address Police Violence As A Public Health Issue; Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation (n.d.) Addressing Harmful Bias and Eliminating Discrimination in Health Professions Learning Environments; and Wispelwey and Morse (2022) An Antiracist Agenda for Medicine. In addition to providing reading material, members of the CAC also drew from one another’s expertise. CAC members such as Artina Sadler have several decades’ worth of experience educating diverse audiences about cultural humility, diversity, equity, inclusion, and systemic racism. Collectively, these resources, CAC member expertise, as well as the trust established among members helped to move difficult conversations forward and on pace with the project timeline.

While CAC meetings 1 and 2 focused on scheduling logistics, determining dates for deliverables, and developing a greater understanding of system racism, meetings 3–8 focused on developing different plan elements such as the plan’s mission, vision, values, goals, and objectives. The vision created for our work was to build “a healthy anti-racist community where equity and justice frames policies and practices.” Core values foundational to our work included equity, justice, compassion, transparency, respect, and trust. Developing a vision and set of core values involved discussion and reflection about what the group aimed to achieve and the intermediate steps and guiding principles needed to get there. Consensus again was reached once all members felt they could “live with the decision.”

In April 2021, the CAC completed the draft of a three-year strategic plan for Genesee County. This plan consisted of goals and objectives for education, employment, health, law enforcement, finance, community networks, and politics. For example, our education goal is to “Provide Anti-Racism Education in Genesee County.” Objectives related to this goal include: 1) Creating a coalition for anti-racism education; 2) Increasing investment and understanding in how racism operates to impact the health and well-being of people of color among all levels of educators (K-12+); 3) Creating a policy that requires K–12 anti-racist education; 4) Creating curriculum for K–12; 5) Creating a policy that requires anti-racism education for all college and university majors; and 6) Creating curriculum for all colleges and university majors.

Once the draft was completed, four online focus groups were held to obtain community feedback. Participants were recruited through direct email using a list generated by CAC members and other community contacts (Taskforce, Faith-based Subcommittee, and CBOP). Recruitment emails encouraged those contacted to forward information about the focus groups to their contacts and listservs. Focus groups occurred in June through July 2021. Participants were compensated $30 for their time and effort. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, each focus group was held over Zoom and recorded. Transcripts generated by Zoom, meeting notes, and video recordings were all used to extract and verify focus group feedback.

There was a total of 25 focus group participants. The majority of participants were women (60%), African American (44% vs. 32% white, 20% Hispanic/Latinx, and 4% Other), and residents of Flint (60% vs 40% non-Flint residents). Importantly, focus group participants helped identify six additional priority areas for addressing racist policies and practices in Genesee County, which were: 1) The school-to-prison pipeline or addressing disciplinary actions and policies in K–12 that drive children of color into the juvenile and criminal justice systems; 2) Law enforcement utilizing options other than incarceration for those with mental health and/or substance abuse issues; 3) Teaching financial literacy to youth and beyond; 4) Improving access to community resources and services such as transportation among Limited English Proficient (LEP) persons and persons with disabilities; 5) Increasing people of color in the public health and healthcare labor force, especially bilingual professionals; and 6) Developing opportunities to promote rest and care for those engaged in anti-racism work. These additional priority areas were brought to the CAC for consideration and adoption.

Three additional CAC meetings were held (a total of 11 project meetings) to finalize our strategic plan to address racist policies and practices in Genesee County. Meetings 9 and 10 focused on reviewing focus group data and suggested revisions to the plan while meeting 11 focused on revising the final plan document. The additional priority areas identified by focus group participants were incorporated into the strategic plan without debate. As these priority areas came directly from residents, consensus about their relevance and significance to the plan was quickly reached.

As meetings 9-11 were occurring, the lead researchers on this project contracted with Flint Innovative Solutions to create the Beyond Rhetoric website. The website officially launched in February 2022, making our work on the strategic plan visible to all. Having the plan become a public-facing record and resource was important. First, it honors the time and effort our community partners put into this endeavor. Second, and perhaps most importantly, it raises awareness, invites collaboration, and holds us accountable for going beyond the rhetoric. While our community-university partners throughout this process have and remain champions of the strategic plan, we recognize the need for larger and broader community adoption to truly advance this work. To this end, Phase 3 of our project is focused on partnering with the Community Foundation of Greater Flint (CFGF), a major philanthropic organization within Genesee County, to bring together local decision-makers and community residents to engage in a participatory modeling process to better understand and dismantle root causes of systemic racism. In partnering with CFGF, we aim to bring those who possess the authority to institute change to the table by leveraging CFGF’s well-established relationships with local decision-makers.

Enacted CBPR Processes

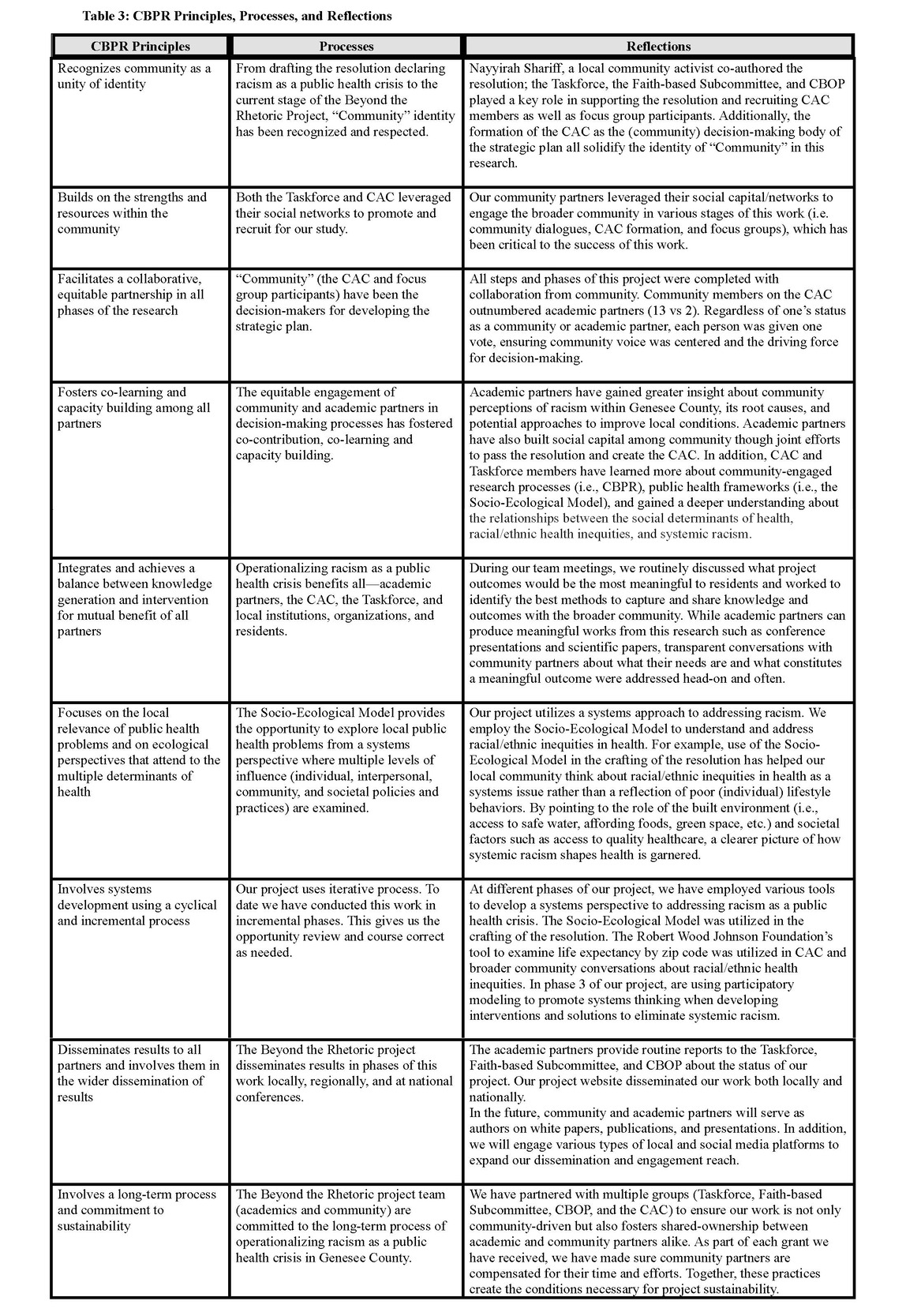

While the presentation of study results is beyond the scope of this work, which is ongoing, Table 3: CBPR Principles, Processes, and Reflections highlights key CBPR principles and processes we have enacted. This summary is offered to provide CBPR practitioners with tangible examples of how community and academic partners can build equitable and sustainable relationships to advance efforts to operationalize racism as a public health crisis and work towards eliminating systemic racism.

Going into any CBPR project requires a long-term commitment from academic and community partners alike. Devoting the necessary time to build trust and engaging in transparent and difficult conversations about needs, expectations, and meaningful outcomes are all cornerstones of building trust and ownership. A common thread throughout the various phases of our project has been collaboration and shared decision-making. We also honor the work of community partners through compensation. Respect, trust, commitment, and appreciation must be demonstrated throughout CBPR projects by both word and action.

Implications

Through the process of developing a strategic plan to address systemic racism in Genesee County, we have learned a number of valuable lessons. Perhaps one of the least surprising, but nonetheless important, is that while community members may come willingly to the table to discuss racism and anti-racism, few people, Whites and people of color alike, have an understanding of institutional and systemic racism. Developing a common language and providing readings and resources for our CAC members to read on their own were critically important to keeping our project moving forward. A lack of understanding regarding how systemic racism operates significantly hampers our ability as community members and public health professionals to envision upstream solutions that address racism as the root cause of health inequities experienced by people of color. Time must be devoted to developing this understanding so that efforts to address racism center on the policies, practices, and intuitions that create and maintain systemic racism.

One tool we found especially useful for discussions concerning the relationship between the SDoH and health inequities is the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s interactive tool found at: https://www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/interactives/whereyouliveaffectshowlongyoulive.html that allows one to examine differences in life expectancy by zip code. When using this tool, we input a Flint address and compared life expectancy with that in Grand Blanc, both of which are located in Genesee County. Grand Blanc, a more affluent area that benefits from longer life expectancy, offers the opportunity to invite community members to discuss why they believe such inequities in life expectancy exist. With very little prompting, community members list factors such as crime/safety, access to grocery stores, water quality, and educational resources as key drivers of these differences. When this happens, we connect their responses to the SDoH and systemic racism. Specifically, we point to deliberate policy decisions such as redlining and the change in municipal water supply that resulted in the Flint Water Crisis (Pieper et al., 2017) as systemic racism, i.e., historical and ongoing systems, laws, and practices that unfairly harm people of color (Braveman et al., 2022). Due to the success we, the academic partners of this project, have experienced in employing the RWJF tool to direct conversations toward system racism among various audiences (i.e., students, county officials, and residents), we strongly encourage others to use it as a starting point for engaging in discussions of systemic racism. We also suggest that supplemental reading material and videos be made available to help ground conversations in research and scientific facts.

Public Health Implications

Although having our CAC members develop an understanding of systemic racism was not a formal goal of our work, we are confident that CAC members today are better equipped to explain and provide examples of systemic racism. As we developed our strategic plan, most CAC members could identify systems (i.e., education, banking/finance, employment, law enforcement, etc.) and align them with the public health framework of the SDoH. Presenting this framework as an approach to understanding racism on a systemic level may prove to be an effective and efficient method for operationalizing racism as a public health crisis. Providing engagement opportunities to discuss how the SDoH impacts health within and across systems provided a deeper understanding of the root causes of racial health inequities. Rather than focusing on individual health behavior and lifestyle choices, these conversations shifted our focus to examining how historic and ongoing unjust treatment hinders people of color from living full, healthy lives.

Addressing systemic racism using community-engaged research approaches, including CBPR principles, guides effective community engagement and collective solutions for addressing systemic racism. CBPR practices ensure the lay community is part of generating solutions to problems they face daily. Their input, perspective, and lived experiences ensure the community is centered when identifying effective responses to systemic racism. CBPR principles also foster co-ownership of solutions generated and increase uptake throughout the broader community. Finally, employing CBPR principles, such as co-creation, can increase trust, transparency, and accountability between the researchers, community members, and other stakeholders. As these groups work together as a collective, it provides a platform for the following: 1) Opportunities for relationship building, 2) New networking opportunities; and 3) The development of new partnerships and coalitions, all of which are essential to carrying out public health work.

Policy Implications

Engaging the community through a public health lens and utilizing community dialogues, focus groups, and other participatory methodologies creates a platform for communities to share their concerns and perspectives with local leaders, policymakers, and other relevant stakeholders. The decision to invite elected officials and other systems leaders to these activities must be intentional and strategic. As has been shared in community gatherings, elected officials and other high-ranking county decision-makers do not want to come to meetings where they are going to get “beat up” and attacked. It’s important to have a community-driven vision to address systemic racism that includes goals and objectives and gives decision-makers something concrete to respond to and work from. Just as community members and researchers have responsibilities for creating positive conditions for collaboration with policymakers and elected officials, these latter groups, too, have responsibilities. Specifically, these groups must: 1) Create clear lines of bi-directional communication; and 2) Ensure friendly spaces and platforms for racism and community-driven solutions to be discussed. To ensure communities understand and participate in the civic process, which is central to how the country is governed, all must work to create the conditions necessary for co-learning and co-creation.