In 2019, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS, 2023a) launched Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America (EHE) as a targeted approach to address HIV in localities where the epidemic is of greatest concern. Broad, national goals for addressing HIV were first established in 2010 with the National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States (NHAS), and the most recent iteration of the NHAS provided national coordination of HIV efforts while the EHE focused on priority jurisdictions (The White House, 2021). Surveillance data used to guide these initiatives indicate Black cisgender women as one of five priority populations and Orange County, Florida, as one of 48 counties deemed priority jurisdictions (The White House, 2021; HHS, 2023a).

The historically disproportionate effect of HIV on marginalized and vulnerable populations is evident in the prevalence of HIV among Black women who must navigate multiple social determinants of health, including racism and sexism, to maintain their health and wellness (Crenshaw, 1989; Essed, 1991; HHS, 2023b). In the U.S., Black women have endured a long history of gendered racism (Essed, 1991) in that their experiences of oppression from the Antebellum period to the present have been shaped by racialized perceptions of gender and gender roles. As a result, Black women seeking sexual healthcare have experienced mistreatment in healthcare settings and have had to contend with dehumanizing sexual stereotypes that depict them as oversexualized, asexualized, and defeminized (Cazeau-Bandoo & Ho, 2022). Within healthcare settings, gendered racism is a contributing barrier to care for Black women (Dale et al., 2019) and contributing factor to the stark incidence and prevalence rates of HIV within this population.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2024), 47% of women newly diagnosed with HIV in the U.S. are Black. The incidence rate for Black women is 10 times that of white women and four times that of Latina women (HHS, 2023b). Estimates of lifetime risk of HIV diagnosis demonstrate the stark inequities in HIV incidence (Hess et al., 2017). Whereas 1 in 54 Black women have a lifetime risk of contracting HIV, the risk is much lower for Latina women (1 in 256) and white women (1 in 941). Nationally, Black cisgender women are the fourth most affected population after Black, white, and Hispanic/Latinx men reporting male to male sexual contact. Local HIV prevalence reflects this surveillance data. In Orange County, Florida, Black women have the third highest HIV prevalence rate (953.6 per 100,000) after Black men (1,938 per 100,000) and Hispanic/Latinx men (988.9 per 100,000) regardless of transition category (Florida Department of Health, 2023b).

Given this data, our research team sought to conduct a localized, community-engaged research study aimed at dismantling healthcare barriers to HIV prevention for Black cisgender women in Orange County, Florida, in an effort to support the EHE plan. Considering the target population and the stigma surrounding the topic of interest (i.e. sexual health and HIV prevention), we engaged in this project with intentionality and the understanding that relevant socio-cultural factors might shape the community’s reception of the study and the willingness of potential participants to enroll. Our experiences with recruitment and enrollment of participants confirmed Burnette et al.'s (2014) assertion that “working in a culturally sensitive way requires increased attention, planning, resources, and even time to conduct research” (p. 379). Throughout data collection we faced multiple challenges, including uneven recruitment, slow enrollment, and fraudulent and ineligible responses following our efforts to attract participants via social media. Navigating these challenges revealed the difficult balance of recruiting a targeted group of people while using as many tools as possible. Whereas our study was localized, community-engaged, and in partnership with an established community organization, the use of a broad medium like social media required us to attend to gaps in our research processes, shift our plans, and reconsider how we used our resources, all of which resulted in changes to our timeline. In this article, we describe our research design and recruitment strategies and discuss the specific ways in which recruitment and enrollment of eligible Black cisgender women became difficult. Additionally, we share the resolutions we developed to address the challenges that arose to inform future culturally sensitive, community engaged, participatory research about HIV.

Study Methodology

In response to the HIV disparity evident among Black cisgender women in Orange County, Florida, the purpose of our research study was to explore the unique sexual health needs of this population to determine the extent to which healthcare providers met those needs. Our primary research question was: How can local healthcare providers prioritize sexual health and HIV prevention needs of Black cisgender women in their services to be in alignment with the Orange County Ending the HIV Epidemic plan? Additionally, we had three secondary research questions: 1) What are Black cisgender women’s sexual health and HIV prevention needs?; 2) What are Black cisgender women’s experiences in healthcare settings in general and when seeking sexual healthcare?; 3) How, if at all, are local service providers engaging with Black cisgender women to provide HIV prevention services, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)?

To answer our research questions, we selected a descriptive, cross-sectional study design with interviewing and concept mapping as our methods. Our research design required multiple types of engagement with three target populations: Black women residents of Orange County, Florida, healthcare providers working in Orange County, and community stakeholders assembled as an advisory board to participate in the concept mapping method. The result was a robust dataset that has the potential to inform health equity practices and outcomes for Black women in Orange County who are vulnerable to HIV.

Interviews with Black Cisgender Women

Our goal was to complete 100 one-on-one semi-structured interviews with Black women, which we anticipated would take nine to ten months to achieve. To add a buffer, we allotted 12 months to complete the interviews. To be eligible for an interview, a potential participant had to meet the following criteria: 1) be at least 18 years of age; 2) identify as a cisgender woman; 3) reside in Orange County; and 4) identify as Black, African American, Caribbean, or descended from people of African descent. Although Black transgender women are another important population for HIV prevention, we wanted to center Black cisgender women for this study in order to understand how they are currently being served or not served by local health outlets. In Central Florida, several organizations serve transgender women along with groups specifically designed for transgender women of color; however, few organizations offer programming directly tailored to Black cisgender women despite the epidemiology of HIV transmission in Florida. There is no women-centered sexual health clinic in Central Florida, although such clinics do exist for the transgender population.

The Black women who participated in our study completed a brief demographics questionnaire and an individual interview. Participants had the option of completing the interview by videoconference, by phone, or in person. We believed the flexibility of interview modes would remove possible barriers to participation, but the videoconference interview option became the most popular choice for our participants. Their participation required a maximum of two hours, depending on their responses. The questionnaire and interview included discussions of sex, sexual health, and healthcare experiences. We were aware that these topics were sensitive, and that HIV, specifically, is often associated with stigma. We tried to mitigate these concerns through the formation of our team and our ability to convey genuine care for and solidarity with Black women.

Interviews with Healthcare Providers

To help answer our research questions, we also interviewed local healthcare providers, including employees of local HIV-serving organizations, primary care physicians, and gynecologists. These individuals chose to be interviewed via videoconference, telephone, or in-person, and their interviews focused on current practices and institutional efforts to address the unique healthcare and HIV prevention needs of Black cisgender women in Orange County. Participants for this aspect of the study were recruited through direct contact (e.g., email, telephone) and through established relationships between research team members and local HIV-serving organizations.

Concept Mapping with Stakeholders

Concept mapping is a participatory mixed method that uses qualitative and quantitative methods to graphically represent a topic of interest (Trochim & McLinden, 2017). For this aspect of our project, we recruited community members to serve as stakeholders. These stakeholders reviewed excerpts from our interviews and generated statements to be ranked and sorted to develop concept maps to determine answers to our research questions (see Kane & Trochim, 2007 for stepwise descriptions of concept mapping). To serve as stakeholders, individuals had to be at least 18 years of age, able to attend a series of meetings, and interested in the health and well-being of Black women.

Our Research Team

Prior to the formation of our research team, colloquially called “Team Orlando,” each of us had individually been committed to health equity broadly, and HIV specifically, through scholarship, teaching, and clinical practice. Our shared concerns for the health and well-being of Black women reflected our identification with this population as well as our understanding of the historical injustices that have compromised the physical and mental health of Black women and undermined their bodily autonomy since the Antebellum period (Villarosa, 2021). Each of us had established relationships with community members, Department of Health representatives, and HIV-serving organizations in Central Florida. We included Black women as research assistants on our team and sought to convey relatability and safety in a project designed for Black women by Black women. Ultimately, our team was able to complete 70 individual interviews with Black women, 20 interviews with healthcare providers, and hold nine stakeholder meetings with 8-16 individuals per meeting. Still, we encountered multiple challenges throughout the research process, particularly in terms of recruitment and enrollment of eligible Black women participants. Next, we discuss our methods of recruitment followed by the obstacles we faced in completing this project.

Recruitment Strategies

To reach our target population of Black cisgender women residing in Orange County, Florida, we employed multiple recruitment strategies. Given the legitimate medical and research mistrust held by Black Americans due to historic unethical treatment of Black bodies (Villarosa, 2021) we knew that our efforts to recruit needed to be culturally responsive and rooted in established relationships within the community (Compadre et al., 2018; Gibson & Abrams, 2003; Vaughan et al., 2022; Warren-Findlow et al., 2003; Wright et al., 2022). We took great care in developing recruitment, data collection, and data analysis processes that centered Black women’s sexual health and honored the culture of the community. We were intentional about the language used on written materials and in our oral engagement with participants so that we could ensure they understood all aspects of the study. For example, we made sure to offer a clear, concise definition of cisgender, which was a new term for some and a misunderstood term for others. We also provided linguistic options for potential participants by translating all research materials into Spanish and Haitian Creole.

Further demonstrating the centrality of cultural sensitivity in our research design, we assembled a research team that would allow us to match the race, ethnicity, and gender of the women we sought to recruit (Vaughan et al., 2022). The Black community of Orange County includes individuals of Latin American, Caribbean, and African heritage with Spanish and Haitian Creole among the most widely spoken languages after English. Given the composition of our team (i.e. all Black and Latina women, two of whom were bilingual), we were intentionally visible in all modes of recruitment. We included our photos on recruitment flyers and on the research webpage, and we made appearances at various venues so that potential participants would connect our faces with the research.

Throughout recruitment, we capitalized on the pre-existing presence of our community partner, Let’s Beehive!, Inc. Let’s Beehive!, Inc. is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization located in Orlando, Florida, that is dedicated to educating children and adults about HIV/AIDS through health education workshops and prevention programs. Let’s Beehive!'s services are designed with Black women in mind and aim to increase awareness, reduce transmission of HIV, and improve therapeutic outcomes among those living with HIV/AIDS. Let’s Beehive!'s collaboration on this project facilitated authentic community engagement and trust and provided visibility for the study. As a starting point for marketing and recruitment, Let’s Beehive! engaged with their established business and faith partners through the Business Responds to AIDS (BRTA) and Faith Responds to AIDS (FRTA) initiatives (Florida Department of Health, 2023a). BRTA and FRTA partnerships recognize the valuable role that businesses and faith communities can play in raising awareness about HIV/AIDS, including hosting HIV education events, serving as a distribution point for condoms, and encouraging community members to engage with HIV prevention and care services. Let’s Beehive! informed the BRTA and FRTA partners of our research study and invited them to participate in our community-facing events.

As we prepared to launch our project, we held a town hall meeting to engage members of the community in a discussion about the prevalence of HIV among Black women in Orange County and to hear their perspectives and concerns. To inform segments of the community about Team Orlando and our study, we interviewed with multiple mass media outlets where we discussed the aim of the research project (Dunn, 2023; Peddie, 2022). Additionally, we presented about the study at the EHE Summit hosted by the Central Florida Department of Health, and we wrote an op-ed piece published in the Orlando Sentinel where we prioritized Black women’s sexual health in commemoration of World AIDS Day (Brown et al., 2022). Through the partnership with Let’s Beehive!, we sought authentic engagement with the community through events we organized and held at the Let’s Beehive! office and in local community centers. We participated as an invited vendor at events, including community health fairs, hosted by local organizations. We also met with various groups (e.g., Black Chamber of Commerce, Black Health Commission) to discuss Black women’s health and share information about the study.

We initially thought that recruiting busy healthcare providers would be the most difficult; however, when we presented the project at the EHE Summit, several people enthusiastically completed our interest form. We used subsequent quarterly EHE meetings and direct contact to build relationships with these providers and recruit them for the study. Similarly, several individuals expressed interest in becoming stakeholders early, despite our timeline, which called for a much later involvement of stakeholders in the concept mapping process.

The recruitment of Black cisgender women residing in Orange County required additional targeted strategies and purposive sampling (Bernard, 2006) to identify potential interviewees with experiences of interest. Both online and in-person recruitment efforts were employed. Online recruitment occurred through direct e-mail contact with local organizations and community groups (e.g., sororities, National Urban League, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and Early Learning Coalition of Orange County) and through posts to Let’s Beehive!'s established social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter). In-person recruitment occurred at locations around Orange County, Florida, including recreational centers, colleges and universities, hair and nail salons, faith-based organizations, and Caribbean and African markets. In addition to the events discussed above, we recruited in places where we were invited, such as Black History Month events, and in our workplaces, which included a hospital and two college campuses.

The response to our community engagement efforts was positive. The relevance of our project was acknowledged by Black women and other community members, local leaders, media personalities, members of HIV-serving organizations, academics, and the local Department of Health. Additionally, multiple non-profit organizations expressed support for our study and committed to assisting with recruitment. Collectively, these responses confirmed the significance of our study, yet this confirmation was unable to guarantee research implementation free of obstacles.

Recruitment Challenges and Resolutions

As mentioned, recruitment of healthcare providers and stakeholders went smoothly; however, the recruitment of local Black women was difficult and forced us to shift course. Specifically, we faced two major obstacles: 1) Uneven recruitment and slow enrollment of eligible Black women; and 2) An inundation of fraudulent and ineligible responses to online recruitment efforts. Both challenges disrupted our momentum, with each requiring unique and intentional modifications to our research methods. Below we discuss these challenges and the methods we took to resolve them.

Slow Enrollment of Black Women

We received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval in May 2022 and proposed to conduct interviews with Black women from August 2022–July 2023, with the town hall in August of 2022 serving as our kick-off event. Since the first three months of recruitment yielded no interviews, our interview period was extended through October 2023 to allow us to reach 70 interviews. As previously discussed, we developed a recruitment strategy that considered the unique needs of our target population. Yet, despite our efforts, enrollment was slower than originally anticipated, reflecting the known complexity of recruiting participants from minoritized groups for health research (Compadre et al., 2018; Gibson & Abrams, 2003; Vaughan et al., 2022; Warren-Findlow et al., 2003; Wright et al., 2022). We knew that our process for study registration and interviewing was streamlined. Interested individuals would be able to access an online interest form where they could read the explanation of research, confirm that they met all eligibility criteria, provide consent, and schedule an interview through a fully online workflow. We also knew that when individuals scheduled an interview, they were likely to complete that interview. Therefore, our focus needed to be on moving potential participants from merely having interest in the study to actually accessing our online mechanism for study registration.

Resolution: Tailored Engagement to Build Trust

In addition to distributing flyers and business cards with a QR code for registration, we also began to carry tablets to community events (e.g., health fairs and cultural festivals) so we could register individuals on-site. We found this approach to be fruitful, increasing the number of individuals who scheduled and completed an interview. The face-to-face contact with individuals that facilitated on-site study registration addressed recruitment challenges discussed in the literature where mailing and telephone contact yield lower response rates for Black participants (Compadre et al., 2018).

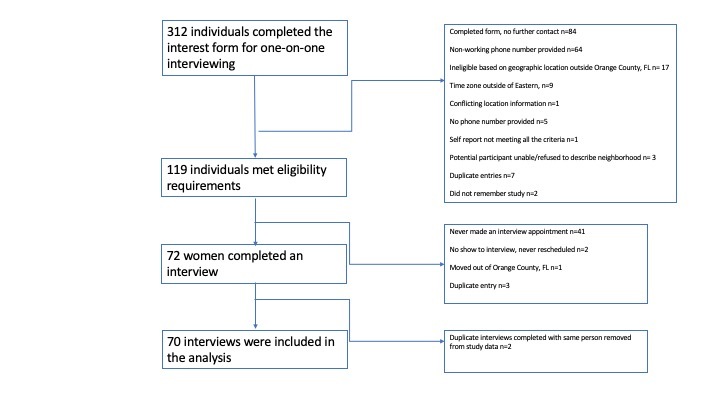

The physical presence of the research team members as individuals progressed through the registration process allowed for trust-building, as we were able answer questions and provide clarification about the research. For instance, some individuals wondered how the data would be used and by whom. We anticipated this question given the historical ways that the medical and research communities have shown themselves to be untrustworthy. We used such questions to build trust with prospective participants by discussing the collaborative nature of the study and the intent of the findings to inform practice. We shared our goals of developing training materials that draw from Black women’s experiences in healthcare and provide practitioners with practical guides to supporting the sexual health and HIV prevention needs of the Black women they serve. In late summer 2023, we also used a recruitment consultant who leads wellness classes with older Black residents in Orlando to generate additional interest in our project. Despite the initially slow response to our recruitment efforts, we eventually gained momentum from October 2022–23 and interviewed 70 local Black women at an average rate of five per month. Figure 1 describes how we arrived at this number of interviews.

Fraudulent and Ineligible Participants

The slow enrollment of participants presented a common challenge in research, so we were relatively prepared for this occurrence and knowledgeable of methods to navigate it. However, we did not realize that potentially ineligible individuals had enrolled themselves in the study and scheduled an interview until we noticed that interviews were being scheduled by people outside of our time zone. Hence, we were unprepared for the sudden influx of potential participants who were ineligible for our study despite their fraudulent claims to the contrary. Ultimately, we had to make modifications to our enrollment process, disrupting the all-online interface.

As mentioned above, we used the social media presence of our community partner as one method of recruitment. Despite specifics in the post that outlined the inclusion criteria, the global reach of our community partner resulted in an overwhelming response to our call for participants from individuals outside of the designated geographical region (i.e., Orange County, Florida). Based on metrics from Instagram, Let’s Beehive! has 944 followers with a distribution of 75% women and 25% men with an age range of 25–54. The account has a geographic reach primarily in Orange County, Florida, and neighboring Seminole County, but also in New York, Puerto Rico, Nigeria, the United Kingdom, and Kenya. Because this was a localized community-based research project that focused on a priority jurisdiction of the EHE, geographic location of participants was critical. Hence, any individuals outside of that region were ineligible even if they met all other criteria.

We received more than 100 fraudulent and ineligible responses following this social media post, requiring us to determine a method of vetting potential participants and safeguarding the recruitment process as we moved forward. Suspicious and fraudulent behaviors included the following: 1) claiming to meet all of the eligibility criteria on the interest form yet providing a wrong or non-working phone number, which made establishing eligibility by phone impossible; 2) Registering for an interview from a time zone other than Eastern; 3) Completing the interest form more than once with only some information duplicated; 4) Being unwilling or unable to provide adequate information to confirm their residency in Orange County, Florida (e.g., address, landmarks etc.); and 5) Completing more than one interview. Our response to this challenge required a multi-pronged approach to ensure the validity of responses and preserve the integrity of the study.

When we designed the process for participants to express interest and register for the study, we prioritized ease of flow so that we would not lose interested individuals from contact to completed interview. We used a QR code, a fillable online form, and an online calendar to allow individuals to access all information about the study (e.g., information about the research team and the explanation of research), confirm their eligibility, provide contact information, and select a date and time for their interview. The process could easily be completed within five minutes from a laptop, tablet, or mobile phone. Unfortunately, the ease of this process allowed individuals with ill-intent to rapidly flood our system. The stark increase in interest for the study raised suspicions which were confirmed when the online calendar indicated that the time zone for several individuals was outside of the United States. With this information, our team convened to discuss possible courses of action.

Resolution: Additional Vetting

As a team, we consulted the literature as well as the IRB that granted approval for the study. The latter was minimally helpful, but the former helped to normalize the experience and provided ideas about how to respond. Duplicate, invalid, and fraudulent responses are likely occurrences given the use of technology within research practices, especially the recruitment of populations that are hidden, vulnerable, or difficult to access (Ballard et al., 2019; Koo & Skinner, 2005; Teitcher et al., 2015). Crowdsourcing for participants is useful for acquiring large samples, and often these tools, such as MTurk, include vetting procedures and validity checks to prevent fraud (Mullen et al., 2021; Rivera et al., 2022). Similarly, online survey tools such as Qualtrics include mechanisms to prevent multiple attempts and estimate geolocation based on an IP address (Ballard et al., 2019). Given that we were conducting a localized qualitative study with a specific target population, we had not used such tools, but they informed the eventual development of a process to screen potential participants.

As we considered the steps that we would take to eliminate fraudulent and ineligible respondents, we considered practical, ethical, and legal suggestions from the literature. We found that Ballard et al. (2019) developed an algorithm to detect fraud, which helped us prioritize the criteria that we would use to vet participants. For instance, we identified time zone, as indicated on the online calendar, and zip code, as reported by the participants, as key indicators of geographic location. Additionally, Teitcher et al.'s (2015) multi-level recommendations of how to detect and prevent fraud informed our review of research procedures, leading to the determination that time zone and zip code were insufficient validity checks. Teitcher et al. (2015) also raised our awareness of ethical implications of addressing fraud in research as we considered and immediately rejected methods of external validation such as using search engines and social media to determine participant eligibility. We were unanimous in our belief that such actions would constitute an invasion of privacy. We also agreed that reporting fraudulent behavior to the Internet Crime Complaint Center of the FBI, a possibility discussed by Teitcher et al. (2015), was equally inappropriate since doing so would introduce a carceral dimension into our research centering the Black community.

Ultimately, we decided to include a brief screening interview into our recruitment process to serve as a validity check prior to the scheduling of the research interview. To do this, we had to dismantle the online workflow that we had developed, intentionally complicating the process for completing registration. During the screening interview, which occurred via telephone, potential participants were reminded of the eligibility criteria and asked to verify that they met all criteria. Since residency in Orange County, Florida, was especially critical, we required individuals to do one of the following: 1) state their address; 2) show an identification card or utility bill with their name and address; 3) name their neighborhood; 4) identify roadways in their community; or 5) identify notable landmarks in their community (e.g., stores, shopping centers, places of worship, etc.). Only after their confirmation of their eligibility did they receive access to the online calendar to schedule their interview.

The inclusion of this step required a revision of our research protocol, which was easily approved by the IRB. Although the IRB approval and implementation of this new process occurred quickly, the time required to identify the problem, generate a feasible plan, and screen out the ineligible respondents was considerable. Additionally, the insertion of a screening interview into the process resulted in an increase in time from first contact to interview and the loss of some interested individuals.

Conclusion

Through the challenges and resolutions discussed above, our research team gained insight into how to improve research practices in HIV research with a minoritized group that contends with overlapping forms of oppression (i.e., racism and sexism). We found that increased face-to-face recruitment and enrollment was critical to securing trust with the target population considering the focus of the research. As a team, we decided that we would neither minimize nor overly emphasize HIV in our recruitment, recognizing that either tactic could potentially reinforce HIV stigma. Instead, we framed it appropriately within the context of sexual health and healthcare experiences and made a concerted effort to talk clearly and concisely about the purpose of our research and how the findings would be used. Our ability to dialogue authentically with potential participants addressed their hesitancy and mistrust, making our recruitment and enrollment efforts more effective.

Having to address fraudulent and ineligible responses to our recruitment efforts challenged us to think differently about how social media can be used to reach targeted — and potentially difficult to access — populations. The algorithm fueling various social media platforms can be utilized in the research planning stage to establish parameters for creating advertisements and posts and for determining vetting processes. Establishing parameters to determine participant eligibility when geographic location is a key criterion was a critical lesson as well. We were forced to consider the various ways that potential participants could confirm their residency without alienating them through the process.

Additionally, the challenges around geographic eligibility shed light on the differing ways in which HIV is conceptualized in terms of location. We chose to use Orange County, Florida, as our locale because it is a priority jurisdiction recognized by the federal government through the EHE initiative. However, Orange County has less practical meaning for HIV-serving organizations and the Department of Health, both of which use either larger, regional designations (e.g., Area 7 of Florida’s HIV/AIDS Surveillance program includes Orange, Seminole, Osceola, and Brevard Counties) or more specific geographical markers, such as zip codes, when considering HIV service delivery. Moreover, community members in this region move easily and often between cities and counties for work, entertainment, and recreation. This means that our focus on Orange County, Florida, might have aligned with the EHE initiative, but it also limited our pool of participants through what could be considered an arbitrary geographic boundary. The lesson here is that recruitment of a targeted population for HIV research must be both broad geographically and specific in methods to be most meaningful and effective.

Community-based research centering the sexual health and HIV prevention needs of Black cisgender women is critical to ending the HIV epidemic in the U.S. (The White House, 2021; HHS, 2023a). It requires strategic planning, a culturally sensitive approach, and flexibility to adjust to the inevitable challenges of recruitment. Attention to location-based considerations is critical, as well, given the role that geography plays in HIV surveillance, prevention, treatment, and viral suppression (Dawit et al., 2023). The lessons learned from our study situated in Orange County, Florida, and centering Black cisgender women’s healthcare needs and experiences provides some guidance for others preparing to conduct similar research.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Interdisciplinary Research Leaders Program 2021-2024.