Introduction

The United States (U.S.) is experiencing a national maternal health crisis that is disproportionately impacting Black and Brown birthing people (Abouhala et al., 2023; Carvalho et al., 2022). According to a review by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MRRCs) from 2017–19, approximately 84% of maternal deaths in the U.S. are preventable (Trost et al., 2022). Additionally, Black and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) birthing people are, respectively, three and two times more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes than White birthing people (Hill et al., 2022). Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in winter 2019, researchers found that maternal mortality rates have increased by about 34% (Hoyert, 2022; Thoma & Declercq, 2022). Of the top causes of mortality, adverse mental health outcomes remain highly prevalent, as about one in every four maternal deaths in the U.S. is due to a mental health-related cause (Trost et al., 2022).

Based on these maternal inequities and experiences, there has been an effort to enact policies to elevate the voices of the Black and Brown birthing community, provide necessary federal and state-level resources to provide medical and socioemotional support, and work closely with communities to co-create health interventions (Carvalho et al., 2021; Wycoff et al., 2024). For example, the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, spearheaded by U.S. Representatives Lauren Underwood (IL-14) and Alma Adams (NC-12), includes a series of 13 bills to improve social determinants of health (SDOH), expand and enhance the maternal health workforce, and design accessible payment models, among other health reforms (Momnibus, 2020). However, major gaps in maternal health policy research remain, including a lack of qualitative research centered on working with birthing communities to directly inform policy change.

Birthing and Parental Health Landscape in Somerville, MA

The costs of raising a family in the U.S. are staggering. One in three U.S. families cannot afford diapers and the price of baby formula and other items continues to increase (Cutler, 2022). The pandemic has only exacerbated the need for diapers, and diaper banks have had to increase distribution to meet the demand (Barbosa-Leiker et al., 2021; McElrone et al., 2021). Parent and infant health disparities vary from state to state and depend on local economic and political standards, such as minimum wage thresholds, paid parental leave policies, and available accommodations in the perinatal period (Chin et al., 2023; Rosenquist et al., 2020).

For instance, Massachusetts has the third-most expensive childcare in the United States, with the median cost of infant care in Middlesex County — home to the city of Sommerville in the Greater Boston Area — totaling more than $26,000 annually (Prignano & Huddle, 2023). These increased costs disproportionately impact low-income families. According to the Community Action Agency of Somerville (CAAS), every 1 in 10 people in Somerville live below the poverty line and White households have 81% higher incomes than Black households, and 47% higher than Latino households (CAAS, 2024). In terms of child health, 16% of children live below the poverty line in Somerville, which has adverse health implications in terms of growth and development (CAAS, 2024).

Additionally, in Somerville, a sanctuary city since 1987, about one-quarter of residents are foreign-born, yet little is explored in the literature regarding multilingual parental health needs (US Census Bureau, 2022). Sanctuary cities protect undocumented immigrants from deportation or legal prosecution even when discordant federal policies may be in effect, and thus draw in large populations of immigrant, refugee, and other displaced communities (LIRS, 2021). Building on a strong reputation as a welcoming city for immigrants and other displaced populations, Somerville-based health experiences allow for the examination of the intersection between immigration and motherhood (Bruhn, 2023). A 2021 ethnographic study among 40 Latina immigrant women in Somerville found that public school-based programming allows mothers to have an opportunity to express their intersectional identities and to hold power as local parents (Bruhn, 2023). This outcome highlights the importance of working with public school systems in reaching immigrant families who may not otherwise learn about or participate in research. Additionally, SomerBaby, as a program through Somerville Public Schools, provides a key opportunity to collaborate with the public school system throughout the research process of Project INSPIRE: Improving New Somerville Parent & Infant Resiliency & Engagement.

While no existing study offers a comprehensive parental health needs assessment for parents in Somerville, particularly in immigrant and low-income families, various prior studies provide some insights into potential community needs. For instance, a 2021 qualitative study among Brazilian women, many of whom reside in Somerville, found that participants strongly relied on organized religion through church congregations as well as social media communications through WhatsApp and Facebook for information-sharing (Priebe Rocha et al., 2022). These insights may inform Project INSPIRE’s modes of outreach for participant recruitment, such as distributing posters to local church groups and virtually on popular social media platforms. Another 2012 survey study assessing occupational health risks among Somerville-based employees found that Brazilian, Salvadoran, and other Hispanic individuals had twice the odds of getting injured at work compared to other immigrants (Panikkar et al., 2012). This study provides necessary context as it indicates that there may be occupational risks or concerns surrounding employment status among our study sample. By having a thorough understanding of this scientific literature on health outcomes in Somerville, the Project INSPIRE team is better able to construct the ongoing study as well as respond to community needs as they arise.

Community Partners & Stakeholders

While research on Somerville-based immigrant parental health needs has been limited, various community and academic organizations have been working to meet local needs. SomerBaby, based at the Somerville Family Learning Collaborative (SFLC) through Somerville Public Schools, is a K-12 community program that seeks to support all Somerville children from crib to college, especially by providing essential information and supplies to low-income, non-English-speaking families since 2016. New babies and their caregivers receive a welcome bag, parenting information, and resources to support their growing families through Nurture Kits. The Nurture Kits initiative aims to mitigate the financial burden of essential newborn supplies. Each kit contains essential baby products, including a diaper bag, diapers, wipes, a few items of clothing, a breast pump, and more. Research and policy groups are increasingly realizing the importance of resource allocation in improving parental and newborn outcomes.

For instance, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) launched a 2023 Newborn Supply Kit campaign, in which community organizations across the country distributed 3,000 kits to families in need and tracked the impact of these resources on family outcomes (Marks et al., 2023). This ongoing initiative found that 97% of families were satisfied with the kits they received and 64% felt less anxious or worried as a result (Marks et al., 2023). In addition to the Nurture Kits initative, SomerBaby’s staff includes doulas and skilled interpreters who provide home visits to immigrant families who need support with caregiving, interacting with the U.S. healthcare system, learning English, or finding employment, among other living necessities.

SomerBaby’s work has recently branched out into the academic medicine sphere through health campaigns, fundraisers, and learning initiatives in partnership with local organizations. Despite these efforts, there remain gaps in the literature on parental health in Somerville. To our knowledge, there are no existing comprehensive parental health needs assessments nor any publications focused on immigrant family health outcomes in Somerville. It is pertinent to fill these gaps to capture local disparities and craft targeted policies that can best meet the needs of families.

Addressing a Community Need — The Birth of the INSPIRE SomerBaby Partnership

In response to these research needs, Project INSPIRE: Improving New Somerville Parent & Infant Resiliency & Engagement, a parental health needs assessment in the city of Somerville, Massachusetts, was constructed. In this, trained bilingual home visitors will conduct a survey with predominantly English-, Spanish-, and Portuguese-speaking immigrant families. A series of ongoing relationships between the academic, community, and medical sectors allowed for the organic formation of this project in response to local needs. First, MARCH: Maternal Advocacy and Research for Community Health, the largest undergraduate-run maternal and child health student organization in the country, was founded in 2020 at Tufts University (Somerville/Medford, MA, USA) in response to exorbitant rates of maternal mortality and morbidity both nationally and globally. MARCH is also a branch organization of the Center for Black Maternal Health Reproductive Justice (CBMHRJ) at Tufts University School of Medicine, a leader in maternal and child health research and community engagement. MARCH aims to motivate, train, and mobilize the next generation of maternal health advocates while elevating local community birthing efforts to bring about social change.

In 2021, MARCH began its partnership with SomerBaby as an initiative to support local maternal and reproductive equity work. MARCH holds annual Mother’s Day Diaper Drives in partnership with SomerBaby, an early childhood support program through Somerville public schools that provides informational, material, and emotional support to underserved families, including non-English speaking and low-income parents (MARCH, 2020; SomerBaby, 2024). In addition to the Mother’s Day fundraiser, MARCH has raised funding for Somerbaby through bake sales and social media campaigns, resulting in at least one fundraising event per semester for the organization since its original partnership. In 2023, MARCH partnered with Somerbaby for the Day of Service of a local community service organization, the Leonard Carmichael Society (LCS), where members distributed and created multilingual posters promoting SomberBaby’s resources throughout local community centers and parks. All diaper and additional resource donations go directly to local families in need in the Somerville area, which SomerBaby, as a community partner, distributes through their home-visiting child health program.

In terms of resource distribution and power distribution, each study collaborator brings a unique set of perspectives and skills. For instance, MARCH serves as a community connector thanks to working closely with SomerBaby officials in the local area, while CBMHRJ represents research and clinical expertise by hosting public health scientists, epidemiologists, and statisticians. Therefore, MARCH members are well-versed in Somerville community needs and have been heavily involved in planning for the 2024 Somerville Family Day alongside SomerBaby, while CBMHRJ is experienced research-scientists who have focused on survey creation based on SomerBaby’s and the Parent Advisory Board’s input, as well as data analysis and interpretation. Representatives from MARCH and CBMHRJ regularly attend recurring research team meetings, allowing for cross-training and collaboration throughout the entire team.

In spring 2023, SomerBaby approached researchers in MARCH and the Maternal & Child Health (MCH) Policy Unit at the CBMHRJ with organizational research needs, specifically in gathering data on the perceived barriers to maternal and child health among parents in Somerville. This need prompted the formation of the Project INSPIRE cross-institutional collaboration, between researchers at the CBMHRJ, students in MARCH, and community leaders at SomerBaby. Additionally, a Parent Advisory Board (PAB) was crafted through support from SomerBaby, in which local Somerville parents directly inform each stage of the research process. The PAB was formed to advise on Project INSPIRE, and SomerBaby staff members helped recruit parent participants by disseminating a call for members to Somerville parents and introducing interested individuals to the study team. The PAB is a five-parent group of Somerville-based parents, including two Spanish-speaking, two Portuguese-speaking, and one English-speaking parents.

Diversity in linguistic, cultural, and immigration backgrounds was critical to forming the PAB, as our team hoped such a group could reflect some of the needs, questions, and lived experiences of other immigrant families in Somerville. The PAB is expected to convene three times virtually throughout the study period, consulting on a different aspect of the study at each meeting. For example, the PAB met in fall 2023 at the start of the study to provide general feedback on the central research questions, existing needs of Somerville immigrant families, thoughts on the study structure, and other preliminary information to help the research team establish the study foundation. Additionally, language interpreters and slides in the three represented languages are available on the virtual calls for accessibility.

Community Empowerment Frameworks

The concept of co-creating research tools alongside community members is a major part of community engagement (CE). CE is an abstract concept that has been utilized more frequently in recent years within health equity projects, and thus can be directly applied into research practice (Cyril et al., 2015). Current research demonstrates that CE, as a research framework, is highly effective in identifying maternal and newborn health needs (Dada et al., 2023). A critical feature of CE-based studies is the inclusion and direct consultation of communities with lived experience throughout project development (Dada et al., 2023). We champion the idea of directly including community voices and knowledge in academic research studies, thereby providing the opportunity for accurate, effective, and far-reaching policy.

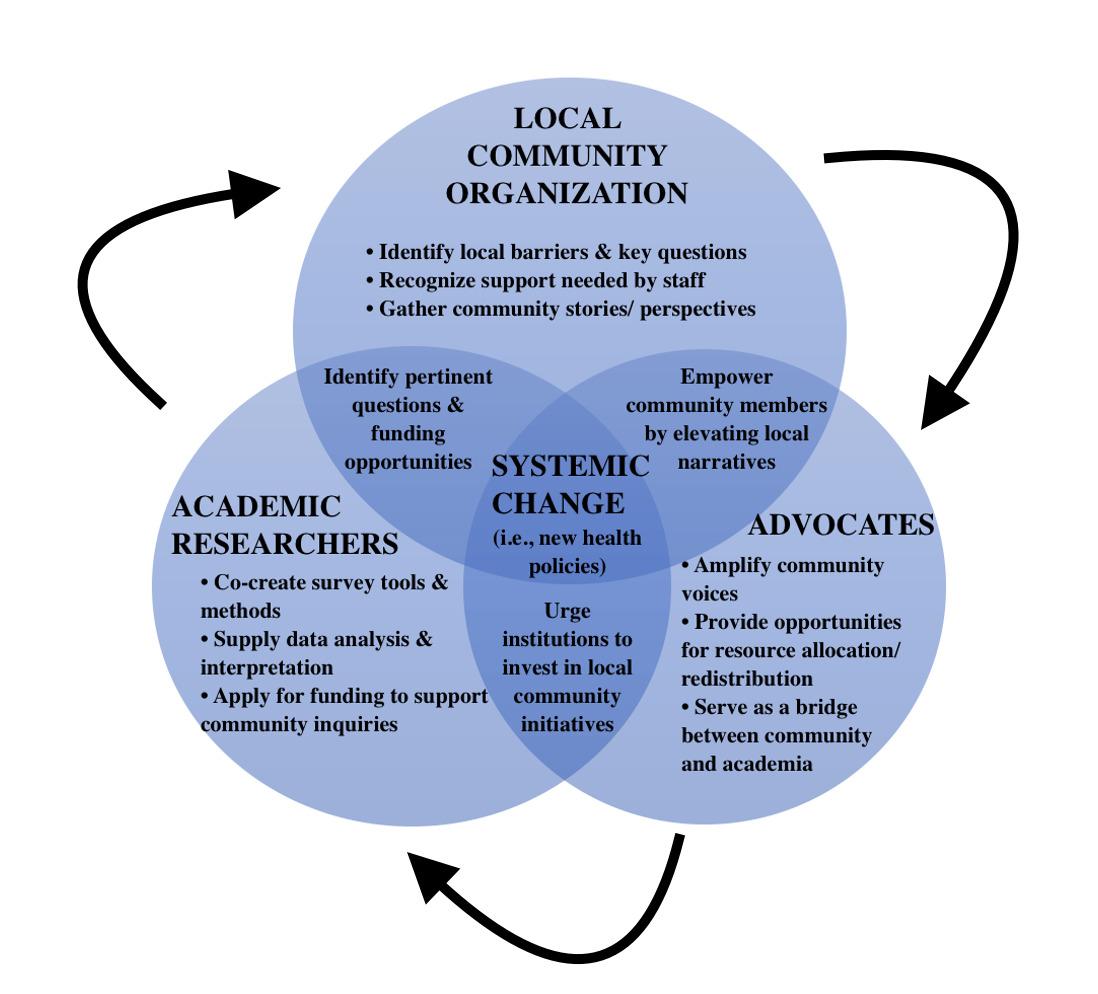

In developing the schema for this project, we paid particular attention to how institutions of higher education and academic research groups can partner with local leaders to provide power (i.e., complete autonomy over the research study) to community partners through a rights-based approach. At the intersection of both CE and a human rights-based approach, the Project INSPIRE team constructed a model to envision the roles and responsibilities of MARCH (a student advocacy group), SomerBaby (a local community organization, and the CBMHRJ (an academic research center): Figure 1: Collaboration among Local Community Organizations, Advocates, and Researchers towards Promoting Health Policy.

Construction and Operation of Project INSPIRE

The purpose of the INSPIRE project is to understand the emotional and material postpartum needs of Somerville families. The project consists of three central phases: 1) parental needs assessment survey creation and dissemination; 2) data analysis and production of accessible research outputs; and 3) planning and facilitating a Somerville Family Day in Summer 2024 for families to learn about the outcomes of this project, hear about helpful organization and local resources, and receive Nurture Kits with essential parental resources (including diapers, breast pumps, baby formula, etc.).

Community & Research Team Convenings

Through this cross-disciplinary project, maternal health inequities researchers at the CBMHRJ collaborated with undergraduate student advocates in MARCH as well as multilingual home-visiting doulas and support staff at SomerBaby on a parental needs assessment survey in Somerville, Massachusetts. While SomerBaby has existed for seven years, there is a gap in understanding the needs and outcomes of Somerville families and there is significant room for improvement in parent outreach and engagement. Thus, the Parent Advisory Board (PAB), consisting of parents who have utilized SomerBaby services, serves as the representative and reflection of Somerville parent voices and needs.

The Tufts Research Team include the collaborators directly involved in research project duties, such as survey creation and participant recruitment, which are the CBMHRJ researchers and MARCH students. The Community Partner Team includes those who contribute lived experiences, linguistic and cultural diversity expertise, community knowledge, and other essential skills to the team, which are the SomerBaby interpreters, home visitors, and Somerville parents. To continuously incorporate community feedback and ensure progression, the Tufts Research Team meets internally biweekly via Zoom. The implementation of these meetings was intentionally set over Zoom to ensure accessibility and flexibility to all involved. This was also necessary as the research team is geographically dispersed across the East Coast. To ensure regular facilitation and feedback by the Community Partner Team, both groups meet quarterly via Zoom. These meetings are safe spaces needed to assess project logistics and progression in maintaining IRB standards and high ethical grounding, as the needs and opinions of our community partners are at the forefront. As a community partner of Somerbaby, we aimed to anticipate and fulfill their needs. At the initial grant kick-off meeting, Somerbaby informed the research team they were hoping to use the survey data in an upcoming grant submission. To ensure we could meet and deliver on this request, the research team edited our timeline, expediting our original timelines by three months.

Survey Formulation: Parental Health Needs Assessment

The research team, alongside the SomerBaby staff and parent advocates, identified three priorities in constructing this survey: 1) identifying barriers related to SDOH (i.e., race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, educational level, language needs, etc.); 2) creating an accessible research tool (i.e., a survey in the commonly spoken languages in Somerville — English, Spanish, and Portuguese — as well as providing both an online and paper version); and 3) collecting data in multidimensional ways to capture contextualized information holistically (i.e., using both quantitative and qualitative survey questions).

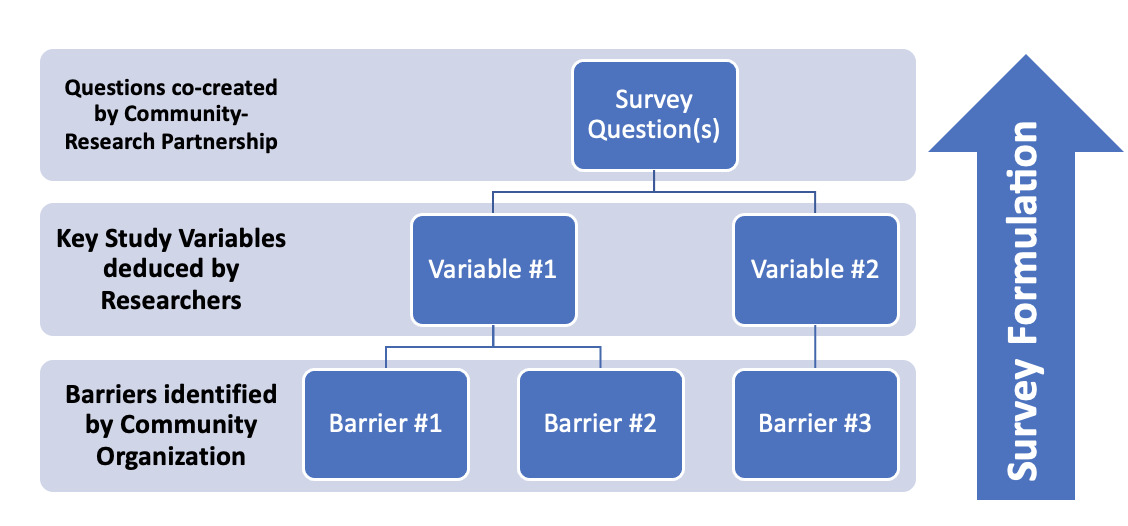

First, in constructing the parental health needs assessment survey, several standardized parent and family health surveys were referenced in order to increase the accuracy and generalizability of Project INSPIRE’s findings. For instance, our team reviewed key questions from the 2022 Maternal and Infant Health Assessment (MIHA) Survey, the 2020 Maternal and Child Health Needs Assessment (MCHNA) Survey, and an internal survey that SomerBaby has previously used to assess the needs of families with children enrolled in Somerville-based public schools. Relevant study variables from these surveys were extrapolated, and questions based on the barriers discussed by SomerBaby staff and Somerville parents were drafted. Most of the quantitative survey questions were based on a Likert scale to provide parents with a variety of options in their responses. For example, one question asked: “On a scale of strongly agree to strongly disagree, please describe how relevant the following statements are to your pregnancy experience (from the time you became pregnant to when you gave birth): ‘I felt sad or mentally unwell,’ ‘I worried about myself or my family having enough food to eat,’ and ‘I had concerns about my immigration status in the United States.’” Furthermore, qualitative questions were included to provide patients flexibility in sharing their thoughts and perspectives. Qualitative questions remained broad to allow parents to elaborate on any relevant areas where they would like to see change in the local community. For example, one question asks: “If the City of Somerville could do one thing for your child, what would it be?” Furthermore, meetings with the PAB allowed the research team to integrate lived experiences in question formulation. For example, in the first meeting with the PAB members, immigration and employment-related barriers were discussed at length. Most parents discussed challenges with finding employment or accessible English language classes in the absence of certain immigration paperwork. Our team had not previously directly asked about these challenges, but this discussion led to us asking related questions, such as “I had concerns about my immigration status in the United States” with Likert scale response options, or “Based on your experiences as a parent/guardian, did you experience any of the following situations?” with options such as “Worrying about keeping your job,” “Worrying about finding a job,” and “Being afraid of facing racism or discrimination from employers.” See Figure 2: Survey Formulation Process for further insight into crafting the survey questions.

Second, in addition to curating questions that accurately inquire about the barriers our community partners have observed through engaging with local constituents, we also aimed to craft a tool accessible to parents, especially those of immigrant, low-income, and/or non-English-speaking backgrounds. For these reasons, we made our survey available in English, Spanish, and Portuguese, which our SomerBaby collaborators identified as the most common languages spoken by parents in the area. Additionally, we designed our survey to be formatted in Qualtrics, an online survey platform, but we also made paper versions that SomerBaby multilingual home-visitors can take with them and distribute to households that lack internet access or who need additional support to complete the survey. The inclusion of this feature was suggested by SomerBaby staff, specifically in the poor access to technology and/or difficulty using technology among under-resourced members of the community. Language translation alone is not sufficient in adapting to cultural, social, or other community-specific needs of Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking families. To tend to these needs, our team implemented two opportunities for elaboration. First, the SomerBaby home visitors/interpreters conducting the surveys in person with families are native speakers of their respective languages, thereby bringing cultural knowledge and other lived experiences to each appointment. During home visitor training, we welcomed the use of dialectical variation, cultural references, or other elaboration on the study questions in the survey, therefore allowing for connection beyond merely the translations. Second, we hope the open-ended questions provide space for parents to share culturally- and/or linguistically-specific barriers, further enriching the data and welcoming qualitative input from participants.

Finally, in determining the specific audience we would target through this survey, our SomerBaby partners and parent advocates discussed the lack of information on lived experiences, local perspectives, and perceived needs among immigrant and low-income community members. Additionally, SomerBaby staff discussed having some data on parents of older children, but a lack of information on the parents of children aged three years and younger (i.e. infants and toddlers). Thus, part of our inclusion criteria is parents who reside in Somerville and have a child three years old or younger. While not explicitly part of the inclusion criteria, in order to sample Somerville parents broadly, our team plans on heavily sampling immigrant parents through the paper version of the survey, as SomerBaby home-visitors mainly serve new parents who are non-English-speaking.

Participant Recruitment & Engagement

As a community-engaged parental health needs assessment focused on immigrant and under-represented families, Project INSPIRE intends to design every step of the project to be as accessible as possible to the community we sought to reach. A critical and important area of focus was language accessibility. We knew that language was a barrier to many of the racially and ethnically diverse communities in the Somerville area. We focused on creating recruitment materials that are accessible to the English, Spanish, and Portuguese-speaking populations. All posters, palm cards, flyers, and other forms of advertising and communication will be delivered in their preferred language(s). Our goal in implementing this multilingual approach is to ensure we cast a wide net and reach new families most in need of Somerbaby services. Somerbaby employs home visitors to provide direct support to new parents, distribute educational materials, and baby bags.

Utilizing the home visitors, a requested research design change made by our Somerbaby partners, during recruitment will be advantageous to the project because home visitors already have an established level of trust with potential participants. In leveraging this trusted messenger approach, we can further identify the specific needs of the community. When potential participants feel comfortable around home visitors, they are more likely to be receptive to completing a research survey to identify their needs and meet service gaps. They are also more likely to answer potentially sensitive or difficult survey questions such as immigration and/or experiences of racism or discrimination during the birth of their child.

In addition, home visitors hold a level of situated knowledge about the population of focus, meaning that they know the best way to introduce the survey to families and effectively communicate the purpose/goal of the research project. Somerbaby has also worked to employ home visitors who speak the common languages in the city of Somerville. This proves that employing home visitors is the best avenue for communication and recruitment between families and the research team. Home visitors also provide a simple way to distribute physical copies of the survey to participants, which increases accessibility to families without internet access. We hypothesize that utilizing these recruitment approaches and communication channels through the Somerville school district and directly with Somerbaby (via the home visitor staff) will serve as an effective method to improve the project’s reach.

Our team also realized that solely relying on data from SomerBaby families may not provide generalizable findings on Somerville parental health needs. For this reason, the survey is also available online to all adult Somerville parents of children three years old or younger. The home visiting modality for SomerBaby parents is an attempt to over-sample immigrant Somerville families, who may be historically underrepresented in research and medicine due to a variety of social determinants of health. To respect the needs and time of these immigrant parents, and to bypass trust, technological, linguistic, or other gaps, the home visiting option is a supportive approach for survey completion and results in a $15 gift card per parent. However, the survey will simultaneously remain open to all adult Somerville parents via Qualtrics (in English, Spanish, or Portuguese), in which online participants may opt into a raffle for a $15 gift card. Of note, this structure was directly suggested by our SomerBaby collaborators, who believed such a model exhibited principles of health equity and prioritized extra study support to minoritized and marginalized communities.

It is important to provide complete autonomy and choice to parents who receive SomerBaby services and to avoid coercion in completing the survey. Our team has worked to mitigate these potentially negative implications in various ways. First, the survey was integrated into existing home visits with SomerBaby families, such that the home visitors were conducting routine appointments with parents and parents were provided the option to complete the survey. By ensuring the survey was an optional component of existing appointments, the research team hoped this would alleviate any pressure. Second, compensation ($15 gift cards) was set to a reasonable but not inappropriate or coercive amount, further contributing to parents’ autonomous decision-making. Through these approaches, the home visiting modality of survey completion provided accessibility to immigrant families who require extra support whether due to linguistic, technological, or other barriers, while minimizing feelings of forced participation.

Lessons in Community-Engaged Policy Research

Project INSPIRE has provided valuable lessons in conducting community-engaged, patient rights-based parental health policy research, especially alongside local child health organizers and non-English-speaking immigrant families. These teachings center humility, flexibility, and collaboration at their core, particularly among academic researchers who may have limited prior experience working in these capacities. It is critical to note that these lessons arose not due to a lack of expertise or background – both professional and personal – in community health, sociological underpinnings, or Black and Brown maternal health experiences. Rather, these lessons are due to a lack of accommodation and community support in traditional academic research models, including health research infrastructures and systems such as ethical review boards, grant applications, mainstream journal criteria, and other restrictions. These standard academic research features make it challenging to conduct community-engaged research, which requires greater flexibility, thorough compensation of community partners, resources for navigating social barriers, and other supports. Therefore, these lessons directly acknowledge such systemic research gaps.

Lesson #1: Call Out Barriers to Inclusion on Academic Research Teams

It is essential for research studies maintain a high level of ethically and socially responsible conduct, which includes but certainly is not limited to: collaboration and approval of research activities alongside Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), comprehensive consideration of ethical implications among research team members, and proper training and preparedness of researchers. These guidelines are necessary to prevent harm and promote accountability across research fields. Many of these protections have been enacted after years of racism and misuse of power in research studies that have targeted Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. Examples of these atrocities include subjecting Alaska Native communities, including the Iñupiaq and Gwich’in peoples, to radiation without their consent in the 1950s, to the forcible sterilization of non-English speaking Mexican women in California in the 1960s and 70s, to withholding effective and available treatment for Syphilis among Black men in Alabama between the 1930s-70s in the infamous Tuskegee Study (Alsan & Wanamaker, 2018; Lanzarotta, 2020; Thurber, 2020).

It is also important to recognize that the academic research process may not be intuitive, particularly for community members who have not previously conducted or participated in research or have limited time to engage in research activities. For instance, a scoping review on challenges faced by community-based research projects in navigating administrative and ethical obligations found that IRBs tend not to consider community members as research team members and that the language required on IRB-related materials (i.e. protocol, consent forms, study documents) is often unaccommodating and beyond the English reading levels of non-English-speaking immigrant participants (Onakomaiya et al., 2023).

Project INSPIRE faced similar challenges, specifically in gaining ethical approval to include SomerBaby home visitors, including experienced doulas and interpreters, many of whom have long-standing relationships and trust with local immigrant families in the Somerville area. One difficulty was including these community members on the central research team due to the requirement of completing the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) certification. CITI programming can take dozens of hours to complete and is well above an eighth-grade reading level, which makes many of these materials burdensome and potentially inappropriate for community partners who lack the time and/or resources to properly complete them. Thus, the questions we are left to face include: is this the best way to assess the self-efficacy and preparedness of community members involved in research processes? Are standardized research certifications simply a measure of time capacity and proximity to academic medicine rather than ethical research tools?

We strongly believe that our SomerBaby collaborators are highly skilled and knowledgeable about local community needs and dynamics, as well as experienced in conducting research and maintaining confidentiality and professionalism thanks to prior projects conducted through Somerville Public Schools. Therefore, we — the academic researchers and students on the study team — advocated for our community members to be included on the central research team by meeting with our local IRB office and discussing alternative options. Upon further discussions with the IRB, we identified a solution that allows the research team to develop a Human Subjects and Research Ethics training for the SomerBaby staff that could be completed in two hours. This training covers all the critical components of human research ethics at a literacy level appropriate for our home visitors. It also includes important training and features of the INSPIRE project. We strongly urge academic researchers involved in community-based research to recognize their power in their institution and to use it to advocate for the inclusion and protection of community partners throughout the research process. Of note, our team is open to sharing the training curriculum to adapt to other studies and invite interested research investigators to email the lead author, SA, for the training materials.

Lesson #2: Remain Flexible in Research Design and Open to Change

In academic or biomedical health research projects, direct community knowledge or involvement in community-engaged research capacities may be viewed as unnecessary, lacking in value, or as an obstacle to streamlining the research process (Ahmed et al., 2004). It is necessary to undo this harmful ideology and understand the power and crucial expertise in community knowledge and partnership. To ensure that community partners and their constituents are heard and respected throughout the research process, researchers need to recognize the flexibility needed in research design, from project conceptualization to delivery. While a research team may initially plan for a project to be conducted in a particular way, community members may decide that changes are necessary to best meet local needs and lived experiences. That knowledge may translate to minor edits or major changes to research plans. Therefore, we recommend that community-engaged research teams include flexibility in their draft protocols as certain activities or frameworks may be subject to change. We also recommend adding extra buffer time into research timelines to account for potential changes recommended by community partners.

In our project, we initially planned for the parental health needs assessment to be distributed as an online survey, in which the first seventy respondents would receive a gift card. However, our SomerBaby community partners noted that many of their immigrant families lack reliable internet access or may not be comfortable using virtual modalities to complete the survey. They also noted that this lack of technological accessibility may result in more affluent or well-connected families completing the survey, thus skewing responses toward specific demographics. These recommendations presented drastic changes to our research protocol, which meant we needed a few more months to restructure the project and complete IRB processes. We are extremely grateful for these comments by our community partners as they made us aware of barriers to participation that we may not have otherwise acknowledged. Therefore, our project is now centered on a home-visiting model, in which multilingual SomerBaby home visitors will support immigrant families with a paper version of the survey. In this capacity, home visitors serve as research team members. This change also means that participants can speak to research personnel in their native language, ask questions about consent or research participation, and feel comfortable sharing their experiences thanks to existing trust in relationships with SomerBaby home visitors. These shifts in our research protocol may have taken additional time to implement but they have allowed us to build a better project that is more accommodating and respectful of community needs and experiences.

Lesson #3: Nothing About Us Without Us

Representation in research teams is of utmost importance in ensuring that all aspects of the research process are constructed and implemented with intentionality and community needs in mind. The “nothing about us without us” approach to health research projects has been used to discuss the need for research projects focused on the outcomes of a particular community to include members of that community on research teams (Albert et al., 2023; Rahman et al., 2022). When constructing Project INSPIRE, we quickly realized none of us are parents in Somerville nor immigrant birthing people with limited English language knowledge. Due to this lack of direct expertise, there may be certain experiences or questions that we were not considering. To bridge this gap, we constructed a Parent Advisory Board, which supported us in developing and piloting our protocol and survey materials before implementation.

For instance, we intended to ask about parental health needs through the lens of healthcare access, such as availability of health insurance coverage, transportation to appointments, and comfortability with providers, among other medical measures. However, the Parent Advisory Board informed us about additional social determinants of health that may impact parental health needs and, therefore, are important to measure. One example is immigration status; parents discussed how difficult it was to complete job applications or other standardized governmental forms when lacking a social security number or certain legal documents. These discussions made it clear that parental health needs would need to be measured in a sociocultural and medical capacity, thus encompassing a broader scope of focus than initially intended. This feedback allowed us to revisit our conceptualization of local immigrant parent and infant health, and to operationalize our study variable through multicultural, systems-level understandings. To this end, we recommend that community-engaged research teams similarly construct inclusive and representative research teams, who are compensated and respected for their time and support.

Finally, there are various conditions to consider before an academic-community partnership is pursued, including feasibility, practicality, and sustainability. Academic teams must build trust with their community partners before initiating a research study or proposal. Central to successful partnership is evidence-based trust, meaning the academic team has consistently and effectively demonstrated support for the community and community improvements. In this case, MARCH and CBMHRJ had a long-standing history with SomerBaby, having organized Annual Mother’s Day Diaper Drives, volunteer events, and joint meetings for years preceding Project INSPIRE. Therefore, we recommend academic teams interested in collaborating with their local community on a research study first begin by genuinely getting to know the community and supporting the community on needs-based projects (ex: resource drives, free educational programming, volunteerism, activism, etc.). Only after long-standing trust has been built can a strong academic-community partnership form.

Translational Health Approaches to Community Resource-Building

The ultimate goal of Project INSPIRE is two-fold: 1) to directly respond to the needs of SomerBaby by equipping them with data on local community barriers as well as further resources through nurture kits at the 2024 Somerville Family Day; and 2) to advance health policy to inform local legislation and health care best practices. The latter is depicted in Figure 3: Development of Health Policy from Community Data. While this publication focuses mainly on the first box, “Gather Needs Assessment (Survey) Data,” as this is central to our discussion about our study’s methodology and lessons gathered, it remains important to consider how academic-community collaboration can be fostered at the other steps. For instance, some pertinent questions to consider when reviewing the following boxes are: How can data be interpreted within the context of community knowledge and lived experiences? In what ways can draft policy suggestions be appropriately distributed to the community? How will community feedback be gathered, stored, and consulted? How can finalized health policies be elevated to legislators, local representatives, and other civic advocates?

In this translational health approach, local health policies can directly reflect and respond to community needs. In this case, academic researchers may serve as the bridge between community narratives and health-related legislation, specifically as synthesizers and data interpreters. Well-contextualized findings allow legislators to gain a holistic perspective on the needs of their local constituents and to respond appropriately to these gaps. Advocates, like MARCH students, are then needed to educate community members on how to make their voices heard and push for such suggested health policies. In this way, all three entities have a direct and crucial role in driving forward health policy: researchers providing the scaffolding for health policy formulation, advocates training community members on pressuring their local representatives to act on these policy suggestions, and community organizers mobilizing constituents to civic engagement through voting, petitioning, phone banking, and other modes of political participation.

In providing suggestions for the translation of research into child health policy, Pulcini et al. (2023) provide four main themes: 1) clarify how these policies would serve as an evidence-based investment for policymakers; 2) craft research questions that will directly support policymaking; 3) engage with local communities; and 4) provide incentives to maximize outreach. Using these guidelines, the Project INSPIRE team plans to draft health policies that are directly informed by survey findings and demonstrate to policymakers and local representatives how investing in low-cost preventative health can improve Somerville parent outcomes. Examples of such policies include: 1) increased local funding for English classes and skill-building workshops to support immigrant parents in search of employment opportunities; 2) a city-funded, new parent resource drive to support the purchasing of diapers, baby formula, and other items for families in need; and 3) investment in parental mental health through accessible therapy services, support groups, and mental health consultations. Additionally, a 2023 policy-making toolkit focused on serving families of diverse backgrounds highlights the importance of Critical Race Theory in adopting an intersectional lens in the health policy sphere (Hull et al., 2023). Finally, the CBMHRJ collaborators in this study are based in the Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Policy Unit, a sector of the Center that directly works on health policy advocacy and advancement within the Black and Brown maternal health spaces. For example, the MCH Policy Unit has consulted on local maternal health legislation, created voter education toolkits, and disseminated educational materials on minoritized maternal health policy both locally and federally. Therefore, our team anticipates that findings from Project INSPIRE will inform MCH Policy Unit’s consultation of local minoritized maternal health legislation. To that end, Project INSPIRE will center intersectional identities in contextualizing research findings and proposing suggested health policies.

Conclusion

Project INSPIRE, a community-academic partnership, is the first community-based parental health needs assessment to be conducted in Somerville and aims to uplift the work of SomerBaby and drive local health policy forward. Through leveraging existing relationships between MARCH, SomerBaby, and CBMHRJ, constructing a Parent Advisory Board for Somerville parents to inform study steps, and creating an accessible survey both in language and modality options, this study strives to provide a framework for future maternal health policy researchers to utilize. Various lessons have been derived from this experience, including building inclusive research teams and maintaining flexibility throughout the research process. In the ultimate pursuit of systemic change and birth equity, Project INSPIRE provides key insights into some of the grassroots work, community collaborations, critical evaluations, and continuous self-reflection necessary in community-engaged health policy research.