Introduction

The correlation between structural racism and health inequities is a longstanding one, deeply rooted not solely in U.S. history, but across the globe (Bailey et al., 2017; DuBois, 1899; Ford et al., 2019; Krieger, 2014). Structural racism, or “the way systems (health care, education, employment, housing, and public health) are structured to advantage the majority and disadvantage racial and ethnic minorities,” is a pervasive force deeply ingrained in all facets of society (Yearby, 2020, p. 518). Its ubiquitous influence is most evident in the lives of racially minoritized people through the prevalence of adverse health, economic, and social outcomes (Paradies et al., 2015; D. R. Williams et al., 2019). Given its ability to shape all aspects of human life, structural racism is considered a fundamental determinant of health (Gee & Ford, 2011).

One of the primary objectives of public health is to promote the health of the public and ensure the conditions for people to be healthy (Institute of Medicine Committee for the Study of the Future of Public Health, 1988). Public health departments, the large governmental institutions tasked with carrying out public health objectives in a jurisdiction, have a specific set of approaches at the ready: assessment, assurance, and policy development (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024). However, structural racism poses a more complex challenge to health equity that cannot be addressed with traditional public health approaches alone. Structural racism involves the interaction of multiple layers of interconnected systems, institutions, and domains of human life in which interpersonal interactions are embedded (Michener & Ford, 2023). These connections are deeply rooted, constantly reinforced in cultural practices and beliefs, and become evident in the power imbalances that exist between communities that are underserved and large institutions (like local health departments) with the power and resources to significantly impact outcomes, for better or worse. Addressing structural racism requires a multi-level, systemic approach that restructures power relationships between community members and institutions by intentionally amplifying the voices of people who have been historically marginalized and underserved, and who have suffered the direct negative impact of structural racism (Michener & Ford, 2022).

Overview

This report describes the challenges and opportunities in conducting a multi-institution participatory evaluation research process in Chicago, Illinois. Both the evaluation process and this report are work products from a collaboration between governmental, community-based, and academic institutions or organizations. We refer to the collective action of community-based organizations and city government to engage in processes that reshape power dynamics to address structural racism in Chicago as interventions in this paper.

The participatory evaluation process described in this report is focused on two health equity interventions described in the next section. In the following section, we conceptualize and define participatory evaluation, delineating it as an approach that is distinct from its traditional conceptualization, and describe our participatory process for writing this report. Our primary objective in this paper is to elaborate on three crucial action points that our team encountered — and continues to grapple with — throughout our participatory evaluation of the interventions. These action points include: 1) determining the purpose and participants of the participatory evaluation process; 2) arriving at shared conclusions regarding the central concepts and goals of the health equity interventions being evaluated; and 3) negotiating a complex web of power relationships among evaluation partners with varying levels of perceived power and trust. The decisions taken at any of these three action points significantly influence the trajectory and outcome of a participatory evaluation project, particularly one focused on addressing structural racism and advancing health equity. We conclude by discussing the implications of how the consideration of these action points might shape future participatory evaluation efforts.

Addressing Structural Racism and Advancing Health Equity in Chicago

In Chicago, Illinois, the third largest city in the United States, the average White Chicagoan lives about 10 years longer than the average Black Chicagoan (Illinois Department of Public Health, Death Certificate Data Files, 2020). In the face of such large racial gaps in life expectancy, the local health department has considered new approaches to address the underlying causes of this inequity. In 2020, the Partnership for Healthy Chicago, made up of the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) and community partners, released the Healthy Chicago 2025 report, Chicago’s current five-year community health improvement plan. The report lays out the following vision:

A city where all people and all communities have power, are free from oppression and are strengthened by equitable access to resources, environments and opportunities that promote optimal health and well-being (CDPH, 2020).

The guiding principles for this work are antiracism, asset-based, equity-focused, trauma-informed, capital-building, and community-led action (CDPH, 2020). Healthy Chicago 2025 also explicitly emphasizes the need for systems change and reshaping power relationships to address health equity, including within the City government’s own practices (CDPH, 2020).

The Healthy Chicago 2025 report stipulates actions that support community power and transform systems that oppress people as a means of addressing the root causes of health inequities (CDPH, 2020). Preliminary work on this plan showed that community members want a role in decision-making, but many experience barriers to participation and some have lost faith that their voices can make a difference. This, along with the knowledge that participation in issues that affect one’s health is a human right, has led CDPH to recognize the need to make it easier for people affected by inequities to become involved in health decision-making and to rebuild trust with community members so that they can feel confident that their solutions are valued by CDPH (CDPH, 2020). To remove the social and institutional barriers that limit community members’ ability to make decisions about their own health, Healthy Chicago 2025 calls for a hyperlocal systems change approach. To implement this approach, CDPH created the Healthy Chicago Equity Zones initiative, led by the Community Planning and Equity Zones office, and established the Health Equity in All Policies office using funding from the Center for Disease Control’s OT21-2103 grant as a part of the National Initiative to Address COVID-19 Health Disparities Among Populations at High-Risk and Underserved, Including Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations and Rural Communities. These two offices are charged with carrying out community co-led work, embedding equity into City practices and decision-making, and reducing health disparities of populations most impacted by COVID-19.

The Healthy Chicago Equity Zones (HCEZ) initiative deploys hyperlocal strategies to confront the social and environmental factors that contribute to health and racial inequities. To support community organizations (particularly in Black and Latinx communities), focus funding and effort where they are most needed, and ensure change is led by residents, CDPH funds six Equity Zones, covering all 77 community areas in Chicago. Efforts to directly engage local communities in public health work started with engagement in 2021 focused on increasing COVID-19 vaccination rates. Since then, the HCEZ initiative has evolved to engage community organizations in confronting factors that contribute to health and racial inequities, including identifying hyperlocal priorities around healthcare and social service access, food access, housing conditions, community safety, and the physical and built neighborhood environments (CDPH, 2023).

The newly established Health Equity in All Policies (HEiAP) office supports advancing policies, practices, and decisions across city government that eliminate health and racial inequities and benefit the health of all Chicago residents using a collaborative policy and systems change approach that centers equity. The approach includes facilitating power sharing through transformative community and government partnerships, cross-sector collaboration, and work across multiple government departments and agencies; supporting community-driven policy change; and creating co-owned strategies for addressing health inequities. The main priority areas of the office are informed by Healthy Chicago 2025, and include institutional change, food access, environment, housing, and neighborhood planning and development (CDPH, 2023).

Methods

Participatory Evaluation

Evaluation is an endeavor focused on assessing the “worth” of various activities (Sechrest & Figueredo, 1993). Traditional approaches to evaluation tend to be quantitative, focused on accountability of public sector institutions, programs, and policies, and rooted in the objectivity of researchers (Chouinard, 2013; Sechrest & Figueredo, 1993). Participatory evaluation (PE) represents a departure from typical evaluation approaches. PE is an evaluation approach that centers on meaningful partnership between trained evaluators, program leadership and staff, and other individuals invested in the relevant program (Cousins & Earl, 1992). PE is characterized by groups coming together to produce “action-oriented knowledge” (Garaway, 1995, p. 86).

Multiple partners are involved in the whole process of PE, from defining the purpose of the evaluation and articulating the evaluation questions, to collecting and interpreting the data, and acting on the results (Springett, 2017). The role of the trained evaluator in PE is significantly different from that of an evaluator in a more traditional evaluation project (Cousins & Earl, 1992). While all evaluators must have the necessary research skills and resources to carry out an evaluation, trained evaluators in PE must also be accessible to partners for participatory activities, have the appropriate communication skills to teach partners about evaluation, be motivated to engage in a participatory process, and importantly, be able to tolerate imperfection (Cousins & Earl, 1992). PE allows for a more equitable relationship between evaluators, clients, and the community constituencies the client is endeavoring to serve.

Our mixed methods, theory-driven PE approach involves a partnership between academic researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Public Health (UIC), leadership and staff at CDPH, and specific local non-profit organization leaders in Chicago (Coryn et al., 2011). We assessed two health equity interventions in the city: the Health Equity in All Policies (HEiAP) Office in CDPH and the Healthy Chicago Equity Zones (HCEZ) initiative. As described above, these interventions were identified based on the Healthy Chicago 2025 plan, which emphasized community empowerment in decision-making (CDPH, 2020). Because of the guiding principles that led to these interventions (i.e., asset-based, community-led, and equity-focused), evaluation required an approach that departed from the traditional external evaluator model and instead embedded community decision-making power into the evaluation work as well.

Our evaluation began six months after the interventions started. First, we formed an advisory group (AG) made up of academic, government, and community partners to provide insight and guidance on all steps of the evaluation process. Next, we developed a program theory to explain how and why the combined HCEZ and HEiAP interventions were expected to address structural racism and a logic model to connect the intervention activities with desired outcomes. We then finalized a working draft of our program theory and logic model with the advisory group and co-developed evaluation research questions. At the point of writing, we are refining our evaluation questions, analyzing secondary qualitative and quantitative data, and collecting new qualitative data.

Participatory Writing

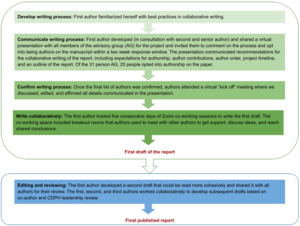

This entire report was written using participatory approaches. Participatory, or collaborative, writing is a process where multiple authors develop a single written report (Christensen & Atweh, 1998). Figure 1 details our participatory writing process, which included shared and directed writing approaches. Shared writing is an approach to collaborative writing where multiple individuals write text in a document and meet to develop a cohesive message (Christensen & Atweh, 1998). This was accomplished through a shared virtual document, Zoom co-working sessions, and two synchronous virtual meetings. The first author (TF) assigned authors to sections of the paper in pairs according to their contribution to the evaluation work; these assignments were affirmed before the writing began. Authors were designated as “writers,” “reviewers,” and “writer/reviewers.” “Writers” drafted the initial text. “Reviewers” contributed their ideas before drafting and reviewed the draft text, providing comments and feedback to enhance or clarify what was written. “Writer/reviewers” served a dual role. An author’s institution did not dictate their contribution to this report (e.g., not all “writers” were from UIC). The Zoom co-working sessions provided the opportunity for “writer”/“reviewer” pairs to meet and discuss their assigned sections. Once we had a first draft of the manuscript, we developed a second draft using directed writing approaches where one person (the first author) took the responsibility of writing a second full draft and completed editing based on group review (Christensen & Atweh, 1998). Subsequent drafts were developed using shared writing approaches between the first, second (KI), and third (SE) authors and confirmed by the full team of authors and CDPH leadership.

Before we began writing this article, our full group of authors engaged in critical questioning and reflection on our work: What should be the focus of the paper? How can our writing reflect the diverse perspectives of multiple partners? From whose perspective should we write? How honest and transparent could we/should we be? The special issue in which we write is composed of articles describing the challenges and successes involved in carrying out action-oriented research partnerships with universities, community-based practitioners, and other institutions aimed at addressing structural racism and advancing health equity. This detailed call made our focus clear. Even so, we grappled with how we should represent our own diverse perspectives cohesively and with radical honesty (B. C. Williams, 2023; Yom, 2018).

Our collective reflection has led us to the following key truths that should guide your understanding of our action points: 1) One truth is that while we have made great progress since this PE project officially began, the project is not where our initial timeline had proposed. Our project is moving “at the speed of trust” (brown, 2017, p. 42), a measure of time that is not aligned with governmental or academic timelines; 2) Another truth is that our advisory group has experienced a wide range of emotions related to this project along the way — from joy and excitement to frustration and anger to anxiousness and trepidation. We hope that our real human emotions are clearly communicated in our description of the process; 3) It is also true that while we identified power, trust, and community organizing as key concepts in our PE, capturing power, trust, or grassroots organizing efforts is not a straightforward task. This reality was an innate limitation to our PE; and 4) A final truth (for now) is that we write this paper while currently in the middle of our ongoing PE process. As such, we do not intend to offer concrete answers or evaluation results; rather, we have months of experiences to share and we offer reflections on how our project has been shaped by our process along the way.

Participatory writing was necessary to clarify the ideas of our large writing team and sharpen our collective understanding of the PE (Christensen & Atweh, 1998). Our collaborative writing offered the group of authors the opportunity to reflect on the project thus far and develop a shared vision for how we would communicate about our work (Christensen & Atweh, 1998).

Challenges and Opportunities for Participatory Evaluation

The following sections detail our individual and collective experiences and reflections from our PE project. Specifically, we detail our actions taken at three key points in this PE process: 1) deciding the purpose and participants of the process; 2) reaching shared conclusions about central concepts and goals of the intervention; and 3) navigating power relationships.

Each section begins with an italicized vignette that tells the story of our experience with the key point before we detail our navigation process. Through the telling of our individual and collective story, we hope we make clear that while this work is not without its challenges and limitations, the opportunities that arise are well worth it.

Key Point #1: Deciding the Purpose and Participants of the Participatory Evaluation Process

“What are we even evaluating?” Before the contract was signed to confirm the research partnership between UIC and CDPH, this was the recurring question on the minds of the team of UIC researchers as we learned about the work ahead. We had read and discussed materials about the health equity interventions that were shared with us but still felt lost and confused. In these early days, few things felt clear amongst our UIC group, and our frustration became palpable: how were we supposed to evaluate work that we did not even understand? So, we met with CDPH leadership. We met with the staff of one of the interventions. And we met with the staff of the other intervention. And we… still did not understand the work. Specifically, how did all these efforts fit together? And still, what are we evaluating? After nine separate meetings spanning two months, we finally reached some points of shared clarity about the purpose of the PE — and a signed contract.

Early meetings between UIC and CDPH led the institutions to decide on a PE approach. As local health department teams that center community power-sharing as a public health strategy and as an academic evaluation team that prioritizes participatory and community-engaged research — we (CDPH and UIC) believed that adopting a participatory approach to this evaluation was fit-for-purpose and a natural, mutual decision. Moreover, the complexity of each of the two health equity interventions required that UIC work in close collaboration with CDPH to identify the goals and outcomes of each initiative, and — more importantly — how each initiative worked separately and together to accomplish those outcomes (see Key Point #2). As Garaway (1995) notes, however, before developing evaluation questions, proposing evaluation methods, or forming an advisory group that could guide us in our work, we needed to create a shared understanding about the purpose of the evaluation: why were we conducting this evaluation, what did we hope to learn, and how would our findings be used? Only then could we identify the key partners who needed to be included in the evaluation process, what their role in the evaluation would be, and how we could engage with them.

There are various rationales for using a PE approach; each understood purpose of PE informs the selection of a different set of participants in the process (Garaway, 1995). For example, if the purpose of the PE is the utilization of the evaluation results, the criteria for selecting participants might be individuals who have the desire and power to make use of evaluation results. Deciding on the evaluation purpose in our PE required multiple in-person and virtual meetings and email exchanges between UIC and key CDPH staff for both health equity interventions.

The key challenge we faced early on in our PE was the sense of urgency we felt to get through deciding the purpose quickly so that we could get started on what we felt was the real work of the evaluation — establishing an advisory group with members outside of CDPH and UIC, collecting and analyzing data about the interventions, and writing a report. Like all grants, the funding for the CDPH health equity interventions and the PE had a limited timeframe; this put pressure on the team to dive into the evaluation work. The UIC team felt the pressure of a two-year timeline to complete an evaluation of what can arguably be described as among the most substantial systems-change initiatives ever undertaken by a health department of this size. UIC saw the potential of these interventions to change the way that public health departments interacted with and prioritized community needs and wanted to provide real-time feedback and quality improvement data to support the work, in addition to measuring outcomes and effectiveness. CDPH also faced rapidly approaching deadlines to collect and report key measures and indicators to internal authorities and external funders to show the progress of the interventions’ work. Our shared sense of urgency meant that these early meetings focused more on making decisions than on intentionally building relationships. However, relationship building in PE is essential, as is taking the time to decide the purpose and participants of the PE. At this very early point of our collaboration, neither partner was actively conscious of the fact that the real work of the evaluation had already begun.

While the team leads for UIC and CDPH were in close communication about contract issues and logistics, the full teams still needed to build trust between one another as well as work through challenges of cross-sector virtual communication that came with the COVID-19 pandemic. It should be noted that our efforts began when COVID-19 protocols still made in-person meetings challenging. We did have some initial face-to-face meetings, but they were conducted with masks on. Both city and university partners felt that initial face-to-face meetings would support relationship building, but the bulk of our conversations and ongoing work were held on Microsoft Teams. Virtual communication certainly has advantages when it comes to ease of participation and scheduling, and we expect reliance on it to continue, but there are limits as well, including the loss of informal interactions such as in-person chats over a cup of coffee. This lack of informal interpersonal interaction can make it difficult to build trust, as was the case in the early days of our PE. As the evaluation progressed, both UIC and CDPH realized this relationship building amongst the participants in the participatory evaluation was an indispensable part of the evaluation itself, not optional preliminary work.

We began to rectify this trust gap by scheduling weekly half-hour check-in meetings with UIC and CDPH. These meetings enabled UIC to communicate their increasing knowledge and understanding about the health equity interventions, provide updates in real-time, and offer support to CDPH in their program monitoring efforts. In turn, CDPH offered UIC the flexibility to move more slowly in the process of defining and refining the evaluation purpose, participants, and methods. Importantly, addressing the trust gap between partners in the early days was a key initial step in our opportunity to work deliberately together throughout the rest of the project. These regular meetings helped to build trust between UIC and CDPH because they provided a space for the continuous exchange of ideas and the sharing of new realities. As such, any decisions made about defining or refining the purpose and participants of the evaluation were consistently shared.

After addressing the trust gap, we determined that the central purpose of our evaluation was to develop a joint learning atmosphere that allowed for the exploration and understanding of the theory of change underlying practice in each intervention, to develop tools that CDPH and partners could use to communicate the logic and activities of their health equity interventions, and to provide ongoing feedback for real-time improvement through a process evaluation (Garaway, 1995). Given this purpose, the participants in our PE needed to be individuals with in-depth knowledge about the implementation of the interventions and the power to make practice changes. This purpose led us to develop an advisory group for the evaluation project that consisted of program staff and leadership at CDPH, staff of local community-based organizations that implement the health equity interventions at the hyperlocal level, and the UIC researchers (Frerichs et al., 2017; Matthews et al., 2018).

We did not recognize the purpose of the evaluation or the ideal participants overnight or after a single meeting, but rather as part of the iterative process described. The iterative work of naming the purpose and participants of the PE was intertwined with our efforts to clarify the theory that underlies the intervention (Linnan & Steckler, 2002). In the next section, we describe our experience of reaching shared conclusions about the key concepts, goals, and overall theoretical framing of the health equity interventions.

Key Point #2: Reaching Shared Conclusions About Central Concepts and Goals of the Health Equity Interventions

“I don’t think I’ve ever heard of someone receiving applause after presenting a program theory before.” By the third quarter of the project, UIC presented their progress on understanding the central concepts and goals of the health equity interventions through a detailed program theory that described how CDPH’s efforts to improve the living conditions of Chicago residents and promote health equity may lead to closing Chicago’s racial life expectancy gap. The program theory version presented was draft number seven and had been iterated over three months through eight different meetings — and it was still incomplete. However, UIC and CDPH were team-learning and that was deserving of applause! We all felt elated. We were making progress on developing a shared understanding of the concepts and goals of the health equity interventions, slowly but surely.

An important feature of this large-scale citywide evaluation project is the logic model designed to describe core components of the interventions that connect planned activities to proposed outcomes (Sechrest & Figueredo, 1993). A tool that communicates the theory of the intervention is essential in any large-scale evaluation (Sechrest & Figueredo, 1993); especially one that includes partners from across institutions who participate in distinct aspects of the two health equity interventions being evaluated and have varying degrees of familiarity with evaluation research.

When our two institutions (UIC and CDPH) first came together, we had a different language for and understanding of the core activities, concepts, and goals of the health equity interventions being evaluated. Both HCEZ and HEiAP are complex, multifaceted, and non-traditional health equity interventions for local health departments, making communication about these programs challenging both within CDPH and externally. Importantly, the underfunding and understaffing of local health departments means that health department staff often must begin projects without reaching consensus about definitions and measurement tools amongst themselves; this presents an additional challenge to collaborative work with an external evaluation partner.

CDPH and UIC’s disparate core understandings of the interventions had the potential to lead us down increasingly divergent paths throughout the PE process. Reaching a shared understanding as a multi-institution evaluation team became paramount. We initiated regular in-person and virtual meetings in late Fall 2022 with the aim of reaching consensus on the central concepts, goals, and overall theory underpinning the interventions. Over the next ten months, and through 26 separate and combined meetings, we developed a series of tools to communicate our growing understanding of the central concepts and goals of the interventions.

The tools that we began to co-develop were visual (see Figure 2). This creative aspect of our PE method — the development of visually-based tools to help facilitate communication between different groups of actors (Chouinard & Milley, 2018) — unfolded organically through our need to communicate complex ideas and conceptual relationships. We found that these visual representations communicated the interwoven nature of the health equity intervention concepts better than paragraphs of text could. These visual communication tools also facilitated the growth of our shared understanding.

The level of detail and complexity that our tools communicate have ebbed and flowed over the life course of the project. These shifts reflect both the growth in our shared understanding and the desire to develop materials to communicate to different audiences (e.g. within the UIC team, across institutions, to governmental leadership).

UIC developed the earliest visualizations. They were detailed and complex flowcharts and logic models based on the initial materials and guidance from CDPH until that point. We quickly learned that these tools did not fully capture the underlying complexities that CDPH wanted to express. The UIC team’s next iteration of communication tools were flowcharts with arrows depicting connected concepts. CDPH provided feedback which led to early drafts of a new kind of document intended to display the historical relationship between the intervention goals, concepts, activities, and outcomes — our program theory. The program theory was based on a systematic review of the CDPH program documents. UIC wanted to make sure that their understandings were rooted in the way that CDPH staff saw their own work, as reflected in the written documents produced by the department over several years. However, given the complexity of these interventions and how they have developed over time, UIC found that even when we closely followed and referenced department documents, we needed conversations with CDPH staff to correct our interpretation of the documents and more closely describe how they saw their own work.

After iterating drafts of the program theory for two months, we began to develop a logic model that documents linear explanations of the relationships between the intervention’s actions and outcomes. The program theory has required eight drafts from its first inception to now. We expect to develop an updated version that can be used to communicate with external partners following the data collection phase. The logic model is also not in its final form and will continue to be updated alongside the program theory for use in different settings with distinct audiences. The latest versions of each document were presented for feedback during our June 2023 AG meeting.

Faced with the challenge of gaps in understanding, our collaborative team turned to visuals to communicate complex ideas. However, the iterative development of the co-designed visual tools was a challenge in itself for two reasons. First, while we experienced large leaps in our shared understanding when we took the time to discuss the materials as a large group, scheduling and other logistical obstacles meant that opportunities to workshop the program theory and logic model across institutions were limited. The back-and-forth editing process through shared documents and emails took a longer time and provided less clear information compared to in-person or synchronous meetings. Second, although the goal of our work at this phase of the PE was to come to a shared understanding about the central concepts and goals of the interventions, the diverse disciplinary perspectives, experiences, and worldviews across and within institutions impacted our process of reaching consensus. This challenge was exacerbated by the differing levels of power (both perceived and real) and trust among members of the AG (see Key Point #3).

Over time, however, our process of developing visual tools to reach shared conclusions about the concepts and goals of the interventions provided the opportunity for us to build trust across and within institutions through listening to one another and subsequently revising drafts. Actors across institutions served as multiple checkpoints to ensure a program theory and logic model that reflects, as accurately as possible, our shared understanding of the interventions from start to projected outcomes. Rather than a single institution shaping the evaluation, our PE process encouraged us to share the responsibility of naming and framing the goal and central concepts of the interventions (Fawcett et al., 2003). However, not all members of the AG saw their perspectives equally reflected in the latest drafts. In the next section of this report, we discuss how we have navigated the array of new and existing relationships across and within institutions, each with differing levels of perceived power and trust.

Key Point #3: Navigating a Multitude of Power Relationships with Differing Levels of Perceived Power and Trust

“How would we benefit from these questions? From the outcome? Because for me, this is solely on the outcome of what you would benefit. ‘You,’ meaning the university. So I’m sitting here kind of ambivalent, and it’s like ‘Damn, why am I sitting here?’ I’ve got 1,001 other things to do.” My (TF) stomach dropped hearing an AG member say those words towards the end of a late Fall 2023 AG meeting after being asked for feedback on the evaluation questions. After hours of meetings and multiple drafts of these questions, I could not believe this was their perspective. Especially since we had brought these same questions before the AG in a previous meeting and were preparing to quickly transition into data collection. However, I tried to just listen. I was frustrated, but I listened. The AG member ended their comments with the same question: “At the end of the day, the question for me is, whether it’s 1 through 7, what will we benefit? How would we benefit?” Following the meeting, I reflected — by myself and in community with a colleague (KI) — and came to some important conclusions about power, trust, and relationships in this project. The "final’’ evaluation questions presented in the AG meeting had been developed mostly in partnership with CDPH and UIC and reflected the needs for grant reporting, CDPH’s future planning efforts, and the loudest voices in the room. Each time the questions were shared with the full AG, the questions were presented for “feedback,” rather than co-development. It is no wonder that the AG member did not value our endpoint — they had no reason to trust the process through which the questions were developed and did not see their priorities reflected in the result.

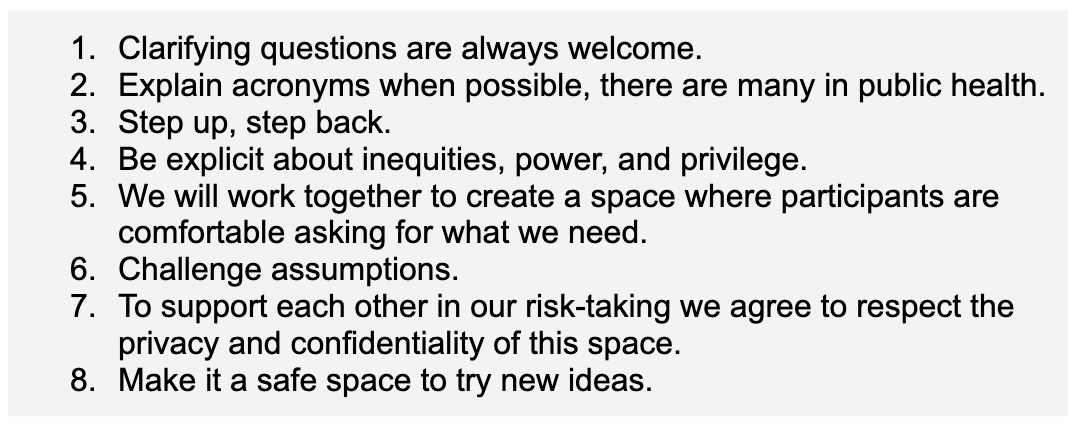

In this report, we define power as the ability to shape the outcome (Morriss, 2006). Early on in this project, UIC and CDPH considered how existing power imbalances between community-based organization members of the AG and each large institution would need to be addressed for the AG to work well together. When our AG met for the first time, we spent the majority of our first meeting introducing ourselves to one another and developing a community contract (see Figure 3) for how we would engage in the AG space and work together on the PE. Our community contract was developed through a modified “Fist to Five” consensus-building activity where we brainstormed a list of community norms and then voted on them by holding up a number of fingers: five for “Yes! Love it,” three for “I have reservations and/or questions that need to be answered, otherwise it’s a Block,” and zero, or a clenched fist, for “No,” which blocks that norm from being added to the community contract. All votes of three were discussed, edited, and voted upon again. The eight norms in our community contract all received unanimous fives from our AG. Our consensus voting process and resulting community contract acknowledged the power and trust differentials between community-based organizations, UIC, and CDPH (Krenn & Community Science, 2021). However, CDPH and UIC had not yet grappled directly with the power and trust differentials that existed within both teams and across the two large institutions.

About three months after the contract was secured, the AG was formed. As the rest of this report has described, UIC and CDPH have worked in tandem from the beginning of this project to decide the purpose and participants of this PE and to develop a shared understanding of concepts and goals. Despite early decisions that a successful evaluation of the interventions would necessarily include actors from outside of their institutions, CDPH and UIC made many decisions about the project before the first meeting of the full AG. We began meeting and making decisions about the project as early as possible because this PE is a grant requirement with a two-year timeline. The interventions being evaluated are funded by a CDC grant that requires CDPH to report specific metrics that reflect the delivery of immediate and short-term outcomes. While UIC and CDPH said that decisions would be flexible pending the later insight of AG members, path dependency meant that we were already leaning in a certain direction and continued in that way even once the AG had been convened. The misalignment between grant reporting parameters and community-identified key parameters is a major barrier to sharing power and building trusting relationships across institutions. Further, convening an AG for “feedback” on fully developed drafts may have left some community-based organization members of the AG questioning their ability to shape the outcome (Michener & Ford, 2022).

The core challenge of navigating the multitude of power relationships in our multi-institution PE is that there are inherent power differentials that are real and gaps in trust that must be closed over time. While it is our goal that all actors share equal power in this PE, we feel that it would be constructive to name some of the existing power imbalances. For example, CDPH retains fiscal control of the interventions and the PE grant, allowing them power over UIC and community-based organization AG members who work on the interventions. While all aspects of the PE are co-designed (an example of CDPH engaging in power with other actors), CDPH holds the final approval power for the PE decisions. UIC is the evaluation expert on this multi-institution team, another form of power over community-based organization AG members and CDPH. Additionally, within any given institution, the differing levels of seniority, decision-making power, and capacity impact one’s individual power in the full group. Trust relationships varied among AG members as well. Some AG members who had worked together in other capacities shared closer, more trusting relationships across institutions than within them. In addition, intention and impact do not always align, so low capacity and heavy workloads within institutions were sometimes translated as intentional exclusion, which also hindered the growth of trusting relationships.

The power differentials and trust gaps required the team to work together differently, providing the opportunity to engage in the power-sharing praxis we were tasked with evaluating. At times, despite agreed-upon community guidelines, power and trust imbalances amongst AG members created tensions and discomfort. However, situations where frustration was expressed and members were able to speak openly and candidly about their perceptions of the process created opportunities for AG members in general, and UIC especially, to pause and reflect on how power differences manifest within an unconventional evaluation process. These moments represent critical inflection points of our PE.

One inflection point was highlighted in the vignette that introduced this section. We can recall another comment from a community-based organization member of the AG who questioned the structure of the evaluation questions in an AG meeting. The initial evaluation questions asked what hyperlocal community networks learn from working in partnership with CDPH but did not ask about what CDPH learned from working in partnership with the hyperlocal community networks. Once brought to UIC’s attention, UIC reflected on the oversight and agreed that this was an important perspective needed in the evaluation questions. Another project inflection point came from a shared working document between CDPH and UIC in late 2023. The editing and comments in the document revealed a disconnect about the core components of one of the interventions being evaluated that could not continue unaddressed. Indeed, the trust that we had been building in our working relationship felt as if it could be negatively impacted if UIC had not taken the time to slow down and address the disconnect. The multi-institution team paused; we met, learned, and moved forward together. During this pause, we were able to embed the concepts of power and trust more firmly into our evaluation questions, adjust our data collection plan, and make specific changes to our spoken and written language to reflect our shared learning. Our PE continues to grow stronger and more rigorous because of our willingness to “be explicit about inequities, power, and privilege” (see Figure 3) and adjust accordingly throughout the process.

Conclusions: A Way Forward

This participatory evaluation began with a call to document, measure, and gain insights into the health equity interventions undertaken by a city health department and its community partners. The primary objective was to generate information that could effectively contribute to maximizing and sustaining the impact of these initiatives. While our multi-sectoral team of evaluators is making significant progress in response to this fundamental call, we have concurrently recognized that the enduring value of our ongoing evaluation will be fundamentally influenced by the collaborative nature of our work: 1) How we have defined the purpose and participants of the evaluation; 2) How we have reached shared conclusions about the central concepts and goals of these initiatives; and 3) How we have navigated power relationships between partners. The manner in which we address these essential action points (Figure 4) establishes the framework for approaching all future aspects of the evaluation. This includes concerns typically centered in traditional evaluations, such as modes of data collection, selection of measurement tools and analysis plans, and the interpretation of findings. As such, we consider the three action points discussed in this paper to be critical and foundational considerations not only for our ongoing participatory evaluation but also for virtually any participatory evaluation of a community-led initiative that involves cross-sectoral partners working collectively across institutions to address structural racism and advance health equity.

Moreover, we regard the task of establishing a foundation of mutual understanding concerning the purpose and participants of the evaluation and goals of the intervention, along with fostering shared power and trust among partners, as essential and continuous elements of a participatory evaluation. These elements are not isolated steps to be completed before the actual evaluation commences; rather, they are integral and ongoing components of the entire process. Therefore, embedded into the planning of any participatory evaluation should be the time required to build relationships, reach shared understanding, and develop mutual trust among partners.

More specifically, sufficient time and resources should be budgeted for the work of identifying and engaging a diverse group of evaluation partners, including community members who are most impacted by what is being evaluated, and for meeting early and often with the partners in a space that allows for all partners to express their unique viewpoints, listen to one another, and reflect on how each diverse viewpoint can be incorporated into the evaluation. Likewise, training in participatory evaluation should include — and ideally begin with — modules focused on strategies for developing shared understanding and mutual trust with evaluation partners. Such time investments should not be thought of as holding up the work of the participatory evaluation; this is the work of the evaluation.

In this light, we offer one final insight into the participatory evaluation of local public health efforts to address structural racism and advance health equity: trust the process, especially when trying new approaches. Cross-sectoral partnerships will undoubtedly involve a variety of barriers to the meaningful engagement that is necessary for reaching shared understanding and developing mutual trust among partners. Grant deadlines, for example, are perhaps the most formidable barriers to meaningful engagement. These are real and cannot be ignored or cast aside. In fact, honoring accountability by meeting deadlines can go a long way towards building trust with some partners. At the same time, however, meeting deadlines with work that is underdeveloped and/or non-representative of all partners’ perspectives (i.e., does not demonstrate a shared understanding) can compromise that trust, and perhaps even impose long-term damage to the relationship. From this perspective, we contend that investments of time for building a shared understanding of the most fundamental aspects of an evaluation and for negotiating power dynamics in the relationship between partners will improve efficiency because these investments lay the foundation for generating more accurate and complete information about a program and its impact on communities — and most likely accomplish this sooner than is possible with traditional evaluation approaches.

This report represents our collective contribution to establishing best practices for partnering across institutions to reshape systems and power relationships to advance health equity. Our previous actions at the key points and lessons learned along the way (see Figure 4) have led our team to the following next steps in our PE:

-

UIC: Continue collecting qualitative data

-

UIC: Conduct preliminary analysis of qualitative and quantitative data

-

AG: Meet to share preliminary findings and discuss interpretation

-

Non-UIC AG: Share preliminary findings with hyperlocal networks to inform our interpretation of the results

-

AG: Meet to share insight gleaned from hyperlocal networks

-

UIC: Interpret findings based on AG and hyperlocal network’s insights and interpretation

-

UIC/CDPH: Meet to share the latest findings and to confirm edits to final visual PE products (e.g. program theory, logic model)

-

UIC: Write the final PE report and develop the final visual PE products

-

CDPH: Strategize for dissemination of final PE products to key audiences

We hope that this radical honesty makes clear the many opportunities that arise from this approach to evaluation and that the insights gleaned from our three key action points enhance the rigor of ongoing and future participatory evaluation efforts of innovative interventions in other jurisdictions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- original draft, Writing- review & editing, project management (Tiffany N. Ford); Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- original draft, Writing- review & editing (Kelechi Ibe-Lamberts, Sydney Edmond); Conceptualization, Writing- original draft (Isabel Abrams, Candice Gary, Stephanie Salgado, Nancy Valentin, Alisa Velonis, Benjamin Shaw); Conceptualization, Writing- review & editing (Minyoung Do, Patrick Daniels, Brian Edmiston, Sona Fokum, Jeni Hebert-Beirne, John Jones, Jess Lynch, Nicole Marcus, Eve C. Pinsker); Writing- review & editing (Aeysha Chaudhry, Diana Ghebenei, Hodan Jibrell, Maura Rose Kelleher, Abha Mahajan, Simone Taylor, Genese Turner)

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of the late Dr. Joyce Chapman to this participatory evaluation project. We would also like to recognize the additional members of our advisory group who have contributed to this participatory evaluation along the way: Jessica Biggs (Southwest Organizing Project), Ruby Ferguson (Greater Chicago Food Depository), Nikhil Prachand (Chicago Department of Public Health), Mike Tomas (Garfield Park Community Council), and Kathryn Welch (Greater Auburn-Gresham Development Corporation). We also acknowledge those who have supported the initiatives being evaluated, including Illinois Public Health Institute, Public Health Institute of Metropolitan Chicago, and Chicago Department of Public Health leadership and staff, including the Community Planning and Equity Zones and Health Equity in All Policies offices, specifically Paula Crose, Megan Cunningham, Aia Hawari, Isaac Marrufo, Susan Martinez, Kate McMahon, Veeta Nowell, Eduardo Muñoz, Clayton Oeth, Kyle Sullivan, and Rahel Woldemichael.